Abstract

Knee pathologies including focal cartilage injuries, osteoarthritis (OA), and ligament injuries are common. The poor regeneration and healing potential of cartilage has led to the search for other treatment modalities with improved healing capacity. Furthermore, with an increasing elderly population that desires to remain active, the burden of knee pathologies is expected to increase. Increased sports participation and the desire to return to activities faster is also demanding more effective and minimally invasive treatment options. Thus, the use of biologic agents in the treatment of knee pathologies has emerged as a potential option. Despite the increasing use of biologic agents for knee pathology, there are conflicting results on the efficacy of these products. Furthermore, strong data supporting the optimal preparation methods and composition for widely used biologic agents, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC), largely remain absent from the literature. This review presents the literature on the most commonly employed biologic agents for the different knee pathologies.

Musculoskeletal diseases are particularly prevalent, with knee pathology among the most common diseases (Schiller et al. 2012, Cross et al. 2014). These constitute both acute injuries and degenerative diseases including osteoarthritis (OA). Specifically, between 1999 and 2008 the number of total knee replacements due to OA in Scandinavia more than doubled (Robertsson et al. 2010). This translates into an annual cost of $462 billion dollars to the economy, secondary to lost wages and the costs of treatment (Mather et al. 2013). An epidemiological study showed an annual incidence of 2.3 knee injuries per 1,000 individuals (Gage et al. 2012). Another epidemiological study from Sweden reported that the incidence of knee injuries resulting in a visit to the Emergency Department was 6 cases per 1,000 person years (Ferry et al. 2014).

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the use of orthobiologics for the treatment of several orthopedic conditions including focal cartilage injuries, early mild to moderate osteoarthritis, and soft tissue injuries (LaPrade et al. 2015, 2016, Zlotnicki et al. 2016). Orthobiologics are substances that are naturally found in the human body, and are used by orthopedic surgeons to improve the healing of cartilage, injured muscles, tendons, ligaments, and fractures (Sampson et al. 2017). These include, among others, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC), and cell-derived therapies. These can be injected directly into the injured structures such as muscle or tendon, or into the knee joint for intraarticular pathologies. Even without many clinical scientific studies, treatment with these agents in sports medicine has also advanced the use of biologic agents in the general population. Furthermore, there is a great desire for athletes to return to pre-injury levels faster, further pushing the use of these products. However, the cost of the development and application of these agents is high, and both have the capacity to increase health care costs.

Despite the growing use of these biologic treatments, limited strong evidence exists either citing the efficacy of the products or providing guidelines for their standard of preparation. The purpose of this review was to evaluate documentation on the efficacy of the biologic treatments utilized in knee pathologies, including platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC).

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP)

The use of PRP to treat sports medicine pathology of the knee has rapidly expanded over the past decade. Classically, PRP was defined as a volume of plasma that has a platelet count “above baseline” during the early stages of clinical research (Zhu et al. 2013). However, this definition has more recently been refined to be more quantitative, requiring PRP to contain more than 1 million platelets per mL (Chahla et al. 2017) of serum or 5 times the amount of baseline platelets (Dhillon et al. 2012). This elevated platelet count in PRP has been suggested as necessary to stimulate targeted injured cells to proliferate (Marx 2001, Rughetti et al. 2008). However, other authors reported that increased platelet concentration beyond the physiologic concentration did not improve functional graft healing in an animal model (Fleming et al. 2015). The biological mechanism driving the clinical use of PRP involves the action of local growth factors in PRP, which modify the inflammatory response, and may affect cell proliferation and differentiation (LaPrade et al. 2016).

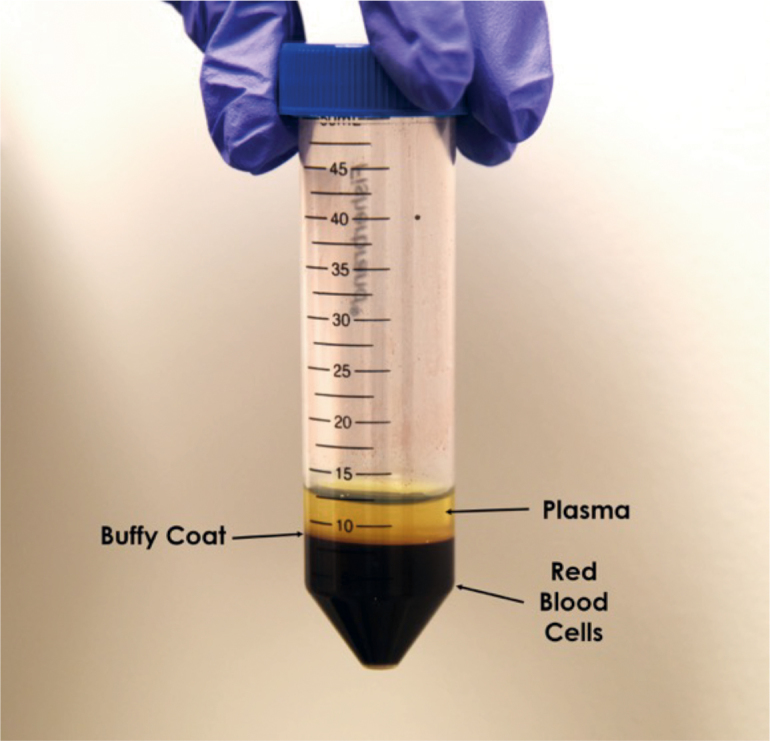

Intra-articular PRP injections for the treatment of focal chondral defects and early mild to moderate osteoarthritis (OA) have been reported to reduce pain, while also improving range of motion and quality of life (Campbell et al. 2015) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preparation of PRP. Following 1–2 spin cycles, three distinct layers can be identified: red blood cells at the bottom, buffy coat containing white blood cells and platelets in the middle, and plasma on top. The buffy coat is removed with a pipette and the plasma is isolated.

Despite these promising results, most of the literature has reported PRP to be beneficial only for a short period of time (Dhillon et al. 2011). The recent systematic review by Campbell et al. (2015) assessed the clinically relevant improvements after PRP treatment for knee osteoarthritis and found that intra-articular PRP injection was an effective treatment for up to 12 months in radiographically evaluated, early-stage OA. Several authors also observed a local adverse reaction, including local swelling and regional pain after serial PRP injections (up to 4 injections), indicating that serial PRP injections to increase effect over time may not be clinically feasible. To evaluate the optimal leukocyte concentration in PRP, Riboh et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis on all randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing the clinical outcomes and rates of adverse reactions between leukocyte-poor (LP) and leukocyte-rich (LR) PRP for the treatment of knee OA. 3 RCTs that used LP-PRP reported positive outcomes compared with hyaluronic acid, while only 1 RCT using LR-PRP reported positive effects versus hyaluronic acid (Riboh et al. 2016). Although several uncontrolled studies have reported pain reduction, functional improvement, and reduced prevalence of surgical revisions and arthrofibrosis (Chahla et al. 2017), further basic science evidence is necessary to determine the effects, if any, of LP- or LR-PRP for intra-articular knee treatment and to evaluate whether one formulation yields superior results.

In vivo anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) healing following PRP treatment has also been studied, with some studies reporting improvement in ACL graft healing as measured mechanically or with magnetic resonance image (Radice et al. 2010, Vogrin et al. 2010, Cervellin et al. 2012). Conversely, other studies have demonstrated no beneficial effects on ACL healing when examining the same parameters (Murray et al. 2009, Nin et al. 2009). A recent systematic review of 11 randomized, controlled studies examined the use of PRP in ACL reconstruction surgery (Figueroa et al. 2015). 6 of the 11 studies reported a faster graft maturation in the PRP group. 1 of 11 studies reported faster healing in the PRP group when examining tunnel widening. Finally, only 1 of the 11 studies reported better clinical outcomes in the PRP group.

Identifying the specific components of PRP which could be responsible for the improved clinical outcomes has been elusive. Some authors noted that interleukin-1 (IL-1) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulated meniscal stem cell migration, while BMP and IGF-1 stimulated fibrochondrocyte migration from the middle to avascular meniscal zones (Braun et al. 2013). An analysis of PRP treatment trends from 2010 to 2011 indicated that 2,571 patients had received PRP injections in these studies, with the greatest number being treated for cartilage defects and meniscal injuries. Notably, PRP injection for ligamentous injuries made up only 7% of the total PRP utilization (Zhang et al. 2016). Despite growing use of PRP, there is a lack of standardized preparation protocols, and variability of application of PRP for the various clinical conditions (Chahla et al. 2017).

In summary, several clinical studies have reported improvements in patient-reported outcomes and a significant reduction in pain scores following PRP treatment in damaged tissue (Kon et al. 2013, Sundman et al. 2014), including tendons and early OA (Riboh et al. 2016). However, there is a paucity of literature with a consistently used methodology to process and activate these PRP formulations, making duplication of similar clinical results after PRP therapy or comparison of the effects of PRP on various musculoskeletal conditions between studies challenging.

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC)

The use of intraarticular bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) to treat various knee pathologies has recently grown in popularity because it is one of the few approaches to deliver progenitor cells that are currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and that can be performed in a single-stage procedure (Gobbi et al. 2015).

For BMAC, bone marrow is harvested and centrifuged to isolate its cellular components in distinct layers and therefore it is considered to be minimally manipulated. This effectively concentrates the mononucleated cells (white blood cells (WBCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), and platelets), in one layer and the red blood cells in another. MSCs are of particular interest because they are capable of self-renewal and differentiation into mature muscle, bone, and cartilage (Fortier et al. 2010). Despite comprising only 0.001–0.01% of cells in BMAC, the MSCs that are present may play a role in healing through homing capabilities that recruit more cells to the injury site (Simmons and Torok–Storb 1991, Dar et al. 2005). MSCs’ regenerative potential, in conjunction with the ability to signal the surrounding tissue to secrete growth factors that modulate the immune response and encourage regeneration at the injury site, suggest that MSC presence provides BMAC with potentially strong regenerative properties, even for avascular tissues like articular cartilage. BMAC has also been reported to contain increased levels of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) and interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β), growth factors that have critical roles in regeneration through immune response modulation, in the joint space (Fortier et al. 2010, Oliver et al. 2015).

Several groups have demonstrated that BMAC is not only safe for patient use, but that it also has the potential to improve pain and activity level in patients with various knee pathologies. Gobbi and Whyte (2016) demonstrated that, after receiving BMAC in a hyaluronic acid scaffold (HA-BMAC), all 50 patients with grade IV chondral lesions showed significantly improved activity and pain outcome scores at 2 years follow-up, and each patient’s function was characterized as normal or nearly normal at 5 years. In comparison, the same study reported a decline in the percentage of patients with normal or nearly normal knee function from two-thirds at 2 years to only one-fourth at 5 years in patients who also had grade IV chondral lesions but who received microfracture instead of HA-BMAC. However, when microfracture was supplemented with a collagen membrane and BMAC, collagen matrix organization began to occur by 1-year follow-up in patients with focal chondral lesions (Enea et al. 2015).

Findings from Krych et al. (2016) support these positive outcomes by demonstrating that, in patients with grades III and IV chondral lesions who were treated with an artificial cartilage scaffold, patients receiving platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or BMAC in addition showed more cartilage fill by MRI after 1 year than patients who were treated with only the control cartilage scaffold. However, only the BMAC group showed MRI T2 relaxation values comparable to superficial hyaline cartilage. Similarly, 22 of 25 active patients with grade IV chondral lesions who received a cartilage scaffold supplemented with BMAC showed integration of the scaffold, while 20 showed complete filling of their lesion by MRI after 3 years.

Skowronski et al. (2013) found positive outcomes after treating large chondral lesions with BMAC similar to Gobbi and Whyte (2016), yet they also concluded that, for a similar population of patients with large chondral lesions, treatment with peripheral blood rather than BMAC yielded better patient outcomes. A recent prospective, single-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study also found that, in patients with bilateral OA, BMAC injections provided after 6 months the same amount of pain relief and increased activity level as saline injected into the patient’s contralateral knee (Shapiro et al. 2017). The findings from this group need to be corroborated by data from longer-term follow-up that includes MRI visualization of any changes in the cartilage structure, but these data suggest that we do not understand the effects that BMAC has on the knee. The studies cited in this review that are in favor of BMAC’s use in the knee largely examined the effects of BMAC in conjunction with a scaffold, while both Skowronski et al. (2013) and Shapiro et al. (2017) found negative and inconclusive results after treating patients with BMAC alone. Thus, despite the data in support of its use for various knee pathologies, the field requires further basic science studies to explain any mechanism of action, as well as strong randomized controlled trials.

Encouraging results have been presented also for patients with moderate to severe osteoarthritis (OA), demonstrating that BMAC injections improved functional activity scores and pain scores (Centeno et al. 2014). Similarly, in patients with chronic patellar tendinopathy, BMAC was found to significantly improve Tegner and International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scores 2 years post-injection (Pascual-Garrido et al. 2012). In a systematic review, which included 11 studies, Chahla et al. (2016) reported a lack of high-quality studies despite growing interest in the use of BMAC. They also reported that the use of BMAC was a safe procedure with reported good results; however, there was a varying degree of beneficial results after BMAC application with and without an additional procedure for the treatment of chondral defects and early stages of osteoarthritis.

In summary, early basic science and clinical studies have elucidated the benefits of BMAC for the treatment of knee pathologies in both animal and human models. The ideal number of BMAC treatments, the volume of treatment, and the timing of injections for BMAC have not been well characterized. Patients with focal chondral defects who received a single BMAC injection have been reported to have improved outcomes (Gobbi et al. 2015). In patients with OA, improved outcomes following BMAC injections have also been reported; however, these studies utilized a variable number of treatments and had limited follow-up intervals (Hauser and Orlofsky 2013, Centeno et al. 2014, Kim et al. 2014). Finally, and most importantly, further clinical studies are needed to identify standardized preparation and application protocols to protect and help patients.

Future directions

Despite the increasing and widespread use of biologic treatment agents in knee pathologies, there are still several areas of controversy and a lack of documentation. There is still no consensus on the optimal protocol for preparing PRP and BMAC. Thus, the products termed “PRP” and “BMAC” are produced differently and have different compositions. It is therefore difficult to compare outcome studies and to evaluate the efficacy of these agents. There is a need to standardize preparation protocols and composition of both PRP and BMAC. There has been increasing interest in the use of scaffolds for the treatment of focal chondral defects. Future research should also evaluate the need for scaffolds in BMAC treatment, and, if one is necessary, what the optimal scaffold is. Therefore, designing optimal scaffolds with the best mechanical and biological properties to treat focal cartilage defects needs further research.

Conclusions

While important advancements have been made in the field of biologics, these therapies are still in their beginnings. In order to advance the knowledge, it is important to first define a minimal standard for each of these treatments and set a clear nomenclature system for reporting. Furthermore, due to the high number of variables that exists when processing these compounds, it is important to characterize the preparation in detail. While most studies suggest having good outcomes with a relatively safe profile, they lack enough power and follow-up time for the evidence to be compelling. Future randomized clinical trials with well-designed and defined protocols with well-defined controls are needed in order to elucidate the real efficacy of these therapies.

Funding and conflicts of interest

No funding was received for this study.

LE: Arthrex Inc (IP royalties, paid consultant), Biomet (research support), iBalance (stock or stock options), Smith & Nephew (research support). RFL: Arthrex Inc (consultant, IP royalties, research support), Ossur (consultant, research support), Smith & Nephew (consultant, IP royalties, research support). GM: research support from South Eastern Norway Health Authorities (Helse Sør-Øst) and Arthrex Inc.

All the authors contributed to the study planning, design, data collection, manuscript writing, and editing.

References

- Braun H J, Wasterlain A S, Dragoo J L.. The use of PRP in ligament and meniscal healing. Sports Med Arthrosc 2013; 21 (4): 206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K A, Saltzman B M, Mascarenhas R, Khair M M, Verma N N, Bach B R Jr., Cole B J.. Does intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injection provide clinically superior outcomes compared with other therapies in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy 2015; 31 (10): 2036–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centeno C, Pitts J, Al-Sayegh H, Freeman M.. Efficacy of autologous bone marrow concentrate for knee osteoarthritis with and without adipose graft. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 370621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervellin M, de Girolamo L, Bait C, Denti M, Volpi P.. Autologous platelet-rich plasma gel to reduce donor-site morbidity after patellar tendon graft harvesting for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A randomized, controlled clinical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20 (1): 114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahla J, Cinque M E, Piuzzi N S, Mannava S, Geeslin A G, Murray I R, Dornan G, Muschler G, LaPrade R F.. A call for standardization in platelet-rich plasma preparation protocols and composition reporting: A systematic review of the clinical orthopaedic literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017; [ePub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, Bridgett L, Williams S, Guillemin F, Hill C L, Laslett L L, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Osborne R, Vos T, Buchbinder R, Woolf A, March L.. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73 (7): 1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar A, Goichberg P, Shinder V, Kalinkovich A, Kollet O, Netzer N, Margalit R, Zsak M, Nagler A, Hardan I, Resnick I, Rot A, Lapidot T.. Chemokine receptor CXCR4-dependent internalization and resecretion of functional chemokine SDF-1 by bone marrow endothelial and stromal cells. Nat Immunol 2005; 6 (10): 1038–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon M, Patel S, Bali K.. Platelet-rich plasma intra-articular knee injections for the treatment of degenerative cartilage lesions and osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19 (5): 863–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon R S, Schwarz E M, Maloney M D.. Platelet-rich plasma therapy—future or trend? Arthritis Res Ther 2012; 14 (4): 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enea D, Cecconi S, Calcagno S, Busilacchi A, Manzotti S, Gigante A.. One-step cartilage repair in the knee: Collagen-covered microfracture and autologous bone marrow concentrate. A pilot study. Knee 2015; 22 (1): 30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry T, Bergstrom U, Hedstrom E M, Lorentzon R, Zeisig E.. Epidemiology of acute knee injuries seen at the Emergency Department at Umea University Hospital, Sweden, during 15 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22 (5): 1149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa D, Figueroa F, Calvo R, Vaisman A, Ahumada X, Arellano S.. Platelet-rich plasma use in anterior cruciate ligament surgery: Systematic review of the literature. Arthroscopy 2015; 31 (5): 981–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming B C, Proffen B L, Vavken P, Shalvoy M R, Machan J T, Murray M M.. Increased platelet concentration does not improve functional graft healing in bio-enhanced ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23 (4): 1161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier L A, Potter H G, Rickey E J, Schnabel L V, Foo L F, Chong L R, Stokol T, Cheetham J, Nixon A J.. Concentrated bone marrow aspirate improves full-thickness cartilage repair compared with microfracture in the equine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (10): 1927–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage B E, McIlvain N M, Collins C L, Fields S K, Comstock R D.. Epidemiology of 6.6 million knee injuries presenting to United States emergency departments from 1999 through 2008. Acad Emerg Med 2012; 19 (4): 378–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi A, Whyte G P.. One-stage cartilage repair using a hyaluronic acid-based scaffold with activated bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells compared with microfracture: Five-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2016; 44(11): 2846–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi A, Chaurasia S, Karnatzikos G, Nakamura N.. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation versus multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large patellofemoral chondral lesions: A nonrandomized prospective trial. Cartilage 2015; 6 (2): 82–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R A, Orlofsky A.. Regenerative injection therapy with whole bone marrow aspirate for degenerative joint disease: A case series. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 6: 65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J D, Lee G W, Jung G H, Kim C K, Kim T, Park J H, Cha S S, You Y B.. Clinical outcome of autologous bone marrow aspirates concentrate (BMAC) injection in degenerative arthritis of the knee. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014; 24 (8): 1505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon E, Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Marcacci M.. PRP for the treatment of cartilage pathology. Open Orthop J 2013; 7: 120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krych A J, Nawabi D H, Farshad-Amacker N A, Jones K J, Maak T G, Potter H G, Williams R J 3rd.. Bone marrow concentrate improves early cartilage phase maturation of a scaffold plug in the knee: A comparative magnetic resonance imaging analysis to platelet-rich plasma and control. Am J Sports Med. 2016; 44(1): 91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPrade C M, James E W, LaPrade R F, Engebretsen L.. How should we evaluate outcomes for use of biologics in the knee? J Knee Surg 2015; 28 (1): 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPrade R F, Geeslin A G, Murray I R, Musahl V, Zlotnicki J P, Petrigliano F, Mann B J.. Biologic Treatments for Sports Injuries II Think Tank Current Concepts, Future Research, and Barriers to Advancement, Part 1: Biologics overview, ligament injury, tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 2016; 44 (12): 3270–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx R E. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): What is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent 2001; 10 (4): 225–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather R C 3rd, Koenig L, Kocher M S, Dall T M, Gallo P, Scott D J, Bach B R Jr., Spindler K P.. Societal and economic impact of anterior cruciate ligament tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95 (19): 1751–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M M, Palmer M, Abreu E, Spindler K P, Zurakowski D, Fleming B C.. Platelet–rich plasma alone is not sufficient to enhance suture repair of the ACL in skeletally immature animals: An in vivo study. J Orthop Res 2009; 27 (5): 639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nin J R, Gasque G M, Azcarate A V, Beola J D, Gonzalez M H.. Has platelet-rich plasma any role in anterior cruciate ligament allograft healing? Arthroscopy 2009; 25 (11): 1206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver K S, Bayes M, Crane D MD, Pathikonda C.. Clinical outcome of bone marrow concentrate in knee osteoarthritis. Journal of Prolotherapy 2015; 7 (2): e937–3946. C [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Garrido C, Rolon A, Makino A.. Treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy with autologous bone marrow stem cells: A 5-year follow-up. Stem Cells Int 2012; 2012: 953510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radice F, Yanez R, Gutierrez V, Rosales J, Pinedo M, Coda S.. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging findings in anterior cruciate ligament grafts with and without autologous platelet-derived growth factors. Arthroscopy 2010; 26 (1): 50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riboh J C, Saltzman B M, Yanke A B, Fortier L, Cole B J.. Effect of leukocyte concentration on the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2016; 44 (3): 792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Bizjajeva S, Fenstad A M, Furnes O, Lidgren L, Mehnert F, Odgaard A, Pedersen A B, Havelin L I.. Knee arthroplasty in Denmark, Norway and Sweden: A pilot study from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rughetti A, Giusti I, D’Ascenzo S, Leocata P, Carta G, Pavan A, Dell’Orso L, Dolo V.. Platelet gel-released supernatant modulates the angiogenic capability of human endothelial cells. Blood Transfus 2008; 6 (1): 12–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson S, Vincent H, Ambach M.. Education and understanding orthobiologics: Then and now In Bio-orthopaedics: A new approach, ed. Gobbi A, Espregueira-Mendes J, Lane J G, Karahan M. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 2017, 41–6. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J S, Lucas J W, Peregoy J A.. Summary health statistics for US adults: National health interview survey, 2011. Vital Health Stat 2012; 10 (256): 1–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S A, Kazmerchak S E, Heckman M G, Zubair A C, O’Connor M I.. A prospective, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial of bone marrow aspirate concentrate for knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2017; 45 (1): 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons P J, Torok–Storb B.. Identification of stromal cell precursors in human bone marrow by a novel monoclonal antibody, STRO-1. Blood 1991; 78 (1): 55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowronski J, Skowronski R, Rutka M.. Large cartilage lesions of the knee treated with bone marrow concentrate and collagen membrane–results. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2013; 15(1): 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundman E A, Cole B J, Karas V, Della Valle C, Tetreault M W, Mohammed H O, Fortier L A.. The anti-inflammatory and matrix restorative mechanisms of platelet-rich plasma in osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42 (1): 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogrin M, Rupreht M, Crnjac A, Dinevski D, Krajnc Z, Recnik G.. The effect of platelet-derived growth factors on knee stability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective randomized clinical study. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2010; 122 (Suppl 2): 91–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J Y, Fabricant P D, Ishmael C R, Wang J C, Petrigliano F A, Jones K J.. Utilization of platelet-rich plasma for musculoskeletal injuries: An analysis of current treatment trends in the United States. Orthop J Sports Med 2016; 4 (12): 2325967116676241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Yuan M, Meng H Y, Wang A Y, Guo Q Y, Wang Y, Peng J.. Basic science and clinical application of platelet-rich plasma for cartilage defects and osteoarthritis: A review. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2013; 21 (11): 1627–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnicki J P, Geeslin A G, Murray I R, Petrigliano F A, LaPrade R F, Mann B J, Musahl V.. Biologic Treatments for Sports Injuries II Think Tank–Current Concepts, Future Research, and Barriers to Advancement, Part 3: Articular cartilage. Orthop J Sports Med 2016; 4 (4): 2325967116642433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]