There was a time, not long ago, when little was known about what happened to survivors of critical illness, and our understanding of outcomes after discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU) was a blank canvas. However, the past three decades have witnessed a rapid acceleration of research in this area. More than 400 studies of outcomes after critical illness have now been published, most within the last 10 years (1). Unfortunately, a meaningful synthesis of this jumble of data is limited by the marked heterogeneity of the approaches used to measure outcomes. A recent scoping review described over 250 unique instruments used in studies of this population. For example, investigators have reported a single outcome—post-traumatic stress—using 15 different instruments at multiple time points, and various approaches for administration (1). In addition, many studies have omitted key data points, which may be inefficient given the significant time, effort, and costs involved in maintaining a post-ICU cohort (2). Overall, this approach to assessment of post-ICU outcomes has painted a picture that is rich but incomplete, chaotic, and difficult to interpret.

One way to find order in the chaos of outcomes research is to develop core outcome sets (COSs). COSs are consensus-based, standardized collections of outcomes for adoption in all trials within a specific clinical area (3), which for many years have been major features of successful advances in clinical research conduct in specialties such as rheumatology (4) and dermatology (5). More recently, COSs have emerged as a methodological approach in critical care in response to the need to converge the proliferation in outcomes assessment of critical-illness survivorship into a more coherent and streamlined means of evaluation. The proposed benefits of a COS include a reduced potential for selective outcome reporting bias, enhanced data meta-analysis, and the inclusion of priority outcomes valued by stakeholders who were previously underrepresented in the research design process (6).

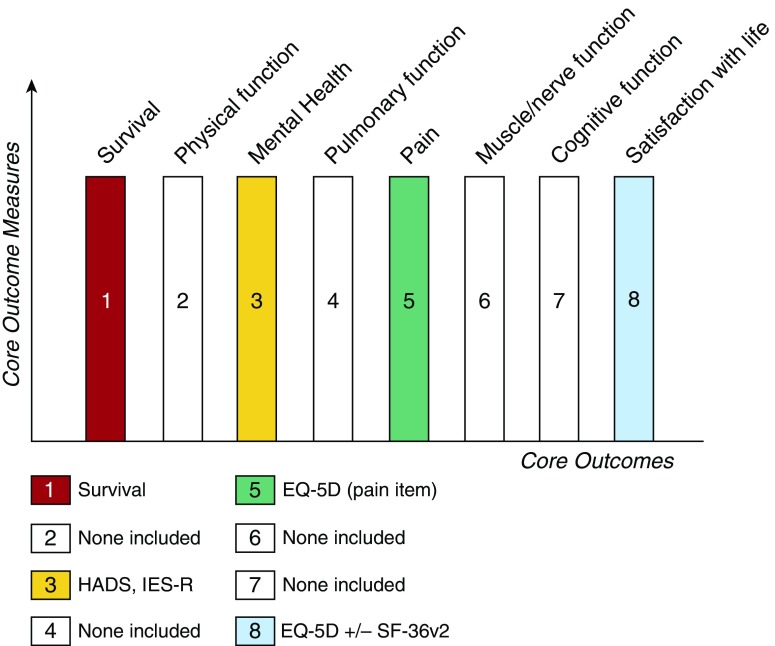

The COS development process broadly focuses on two stages: (1) establishing what outcomes to measure and (2) deciding how to measure them (3), drawing the outlines and then coloring them in. In this issue of the Journal, Needham and colleagues (pp. 1122–1130) address the second stage, reporting the results of their consensus process to determine core outcome measures for use in clinical research in survivors of acute respiratory failure after hospital discharge (7). Preceding work identified eight core domains of outcomes to be evaluated (7, 8), namely, survival, physical function, mental health, pulmonary function, pain, muscle and/or nerve function, cognition, and satisfaction with life or personal enjoyment (conceptually health-related quality of life). The authors’ task in the current study was to identify measurement instruments for outcome evaluation with appropriate psychometric properties and feasible utility. At present, there is no established, consistent taxonomy for describing the steps involved in producing a COS, and different terms are applied to describe collections of core outcomes and, separately, their measures (3–5). To address the latter issue, the authors describe their development of a “core outcome measurement set” (COMS) (7).

With the exclusion of survival (a domain considered to not require consensus for a measurement instrument), measurement instruments were agreed upon for three of the remaining seven core outcomes: the EuroQol five dimensions (EQ-5D) and 36-Item Short Form Survey version 2 (SF-36v2) for “satisfaction with life and personal enjoyment” and “pain” outcomes, and both the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Impact of Event Scale—Revised (IES-R) for “mental health.” These results were neatly tabulated by the authors to provide a succinct précis of the estimated time and financial costs required to complete various configurations of the COMS, as well as the volume of questions required to reflect potential patient burden. This is a valuable interpretation of these findings that should facilitate implementation of the COMS. Furthermore, the authors provide suggestions for expanding the COMS with the highest-ranking (albeit nonconsensus) measurement instruments for other outcomes, such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Blind tool to evaluate cognition.

The COMS suggested by Needham and colleagues is a significant step forward. With successful implementation, use of this COMS across ICU follow-up studies would markedly decrease heterogeneity, increase opportunities for meta-analysis, and substantially add to the body of knowledge about the natural history of recovery after discharge from the ICU, as well as the potential effects of interventions. Notably, the measurement instruments that are included in the final COMS are all patient reported by nature, meaning that it can be completed relatively quickly, simply, and via telephone, negating the need for in-person testing, which can restrict longitudinal follow-up of survivors in both trials and cohort studies. Furthermore, there is confidence that this COMS can be considered a true reflection of stakeholder opinions, with minimal attrition evident and response rates of 91–97% across the three survey rounds from an international multidisciplinary and patient/caregiver panel.

However, this work is certainly not done. First, as Needham and colleagues highlight in their “suggestions for a future research agenda,” measurement properties need to be established for both included measures (such as the “pain” item in the EQ-5D) and candidate measures for the remaining outcomes that failed to garner consensus (cognition, physical function, muscle and/or nerve function, and pulmonary function). Second, new approaches are needed to reduce redundancy in the current COMS—the HADS, IES-R, EQ5-D, and SF-36 all contain overlapping content. Third, new instruments, including those that use item response theory and computer adaptive testing, need to be studied in tandem with the suggested COMS to allow future growth and improvement of the set. New instruments may provide an opportunity for recalibration within the current set, in which measures may not entirely represent the intent of the outcome; for example, using the SF-36, a measure of health status, to measure the outcome of “life satisfaction and personal enjoyment” may be improved upon in the future. Fourth, the science of developing COSs and measures itself will need to evolve and establish its own evidence base to guide future versions and address issues such as how to determine the makeup of the stakeholder group that is participating in the consensus process (9). Finally, it will be important to assess the experience of incorporating the suggested COMS into observational and interventional research.

Although the benefits of adopting the COMS for ICU research are clearly significant, there are potentially negative consequences as well. Although the COMS only specifies the minimum assessment required, and in no way restricts the use of additional measurements, with limited resources and the risk of increasing participant burden, opportunities to explore new domains and new instruments may be reduced, resulting in a “coloring by number” approach (Figure 1). As a research community, we must remember that our understanding of ICU survivorship is incomplete, and that the palette required to paint this landscape has many more than four—or even eight—colors. Implementation of the COMS developed by Needham and colleagues will help focus the image of ICU survivorship. But continued innovations in core outcomes, their measures, and other assessment methods, will reveal the many hues and details and depth of the true experience of life after critical illness.

Figure 1.

A “coloring by number” of the suggested core outcomes and measures for survivors of acute respiratory failure. Four of eight core domains of outcomes for follow-up after hospital discharge (7, 8) are “colored in” with agreed-upon core outcome measures. Those for which there is no consensus on core measures remain blank outlines. HADS = hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IES-R = Impact of Event Scale—Revised; EQ-5D = EuroQol five dimensions; SF-36v2 = 36-Item Short Form Survey version 2.

Footnotes

B.C. is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) postdoctoral fellowship (2015-08-015) and is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1239ED on July 12, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, Nasser MF, Venna VR, Lolitha R, Hopkins RO, Bienvenu OJ, Robinson KA, Needham DM. Outcome measurement in ICU survivorship research from 1970 to 2013: a scoping review of 425 publications. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1267–1277. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abshire M, Dinglas VD, Cajita MIA, Eakin MN, Needham DM, Himmelfarb CD. Participant retention practices in longitudinal clinical research studies with high retention rates. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:30. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Devane D, Gargon E, Tugwell P. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt J, Apfelbacher C, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, Simpson EL, Furue M, Chalmers J, Williams HC. The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) roadmap: a methodological framework to develop core sets of outcome measurements in dermatology. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:24–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson P, Altman D, Blazeby J, Clarke M, Gargon E. Driving up the quality and relevance of research through the use of agreed core outcomes. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17:1–2. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Aronson Friedman L, Bingham C, III, Turnbull AE. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors: an international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turnbull AE, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Bingham COI, Needham DM. Core domains for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors: an international modified Delphi consensus study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1001–1010. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, Barnes KL, Blazeby JM, Brookes ST, Clarke M, Gargon E, Gorst S, Harman N, et al. The COMET handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18:280. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]