Abstract

Coordinating cell growth with nutrient availability is critical for cell survival. The evolutionarily conserved TOR (target of rapamycin) controls cell growth in response to nutrients, in particular amino acids. As a central controller of cell growth, mTOR (mammalian TOR) is implicated in several disorders, including cancer, obesity, and diabetes. Here, we review how nutrient availability is sensed and transduced to TOR in budding yeast and mammals. A better understanding of how nutrient availability is transduced to TOR may allow novel strategies in the treatment for mTOR‐related diseases.

Keywords: amino acids, glucose, mammals, nutrients, RAG, TORC1, yeast

Subject Categories: Metabolism, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Nutrients provide energy and building blocks for organismal growth. An effective response to changes in nutrient availability is crucial for organismal viability. In response to nutrients, the target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway stimulates anabolic processes such as protein, lipid, and nucleotide synthesis, and represses catabolic processes such as autophagy, to ultimately promote cell growth (for review, see Wullschleger et al, 2006; Loewith & Hall, 2011; Howell et al, 2013; Laplante & Sabatini, 2013; Shimobayashi & Hall, 2014). TOR was discovered in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, by mutations that confer resistance to the growth inhibitory effect of rapamycin (Heitman et al, 1991; Kunz et al, 1993). Shortly thereafter, it was identified in mammalian cells (Brown et al, 1994; Chiu et al, 1994; Sabatini et al, 1994; Sabers et al, 1995). TOR forms two structurally and functionally different conserved complexes termed TOR complex 1 (TORC1) and TORC2, of which only TORC1 is sensitive to rapamycin (Loewith et al, 2002). The essential components of budding yeast TORC1 are TOR1 or TOR2, Kog1, and Lst8; the mammalian orthologs are mTOR (mammalian TOR), RAPTOR (regulatory‐associated protein of TOR), and mLST8 (mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8), respectively (Hara et al, 2002; Kim et al, 2002; Loewith et al, 2002). Nutrients, growth factors, and cellular energy regulate TORC1 activity. Nutrients are particularly important TORC1 activators as they alone are sufficient to activate TORC1 in unicellular organisms. Growth factor signaling evolved and was grafted onto the TORC1 signaling pathway in multicellular organisms. Here, we review amino acid and glucose sensing mechanisms and how nutrient availability is transduced to TORC1 in yeast and mammals.

RAG GTPases and their upstream regulators

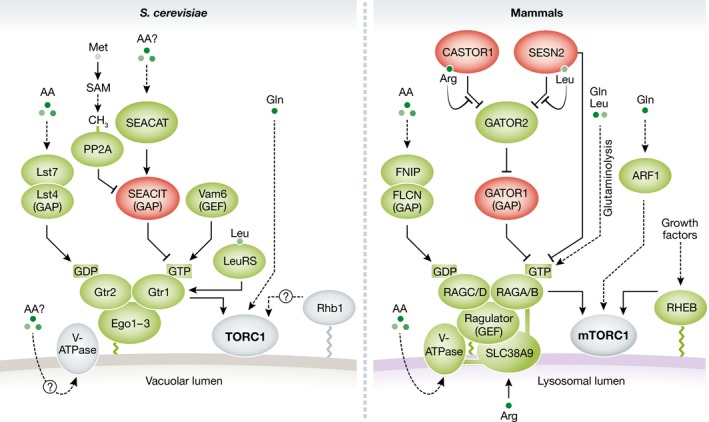

Amino acid sufficiency regulates TORC1 via different mechanisms that largely involve the conserved RAG family of small GTPases (for review, see Jewell et al, 2013; Bar‐Peled & Sabatini, 2014; Shimobayashi & Hall, 2015; Hatakeyama & De Virgilio, 2016; Powis & De Virgilio, 2016; Fig 1). There are four RAGs in mammals (RAGA, RAGB, RAGC, and RAGD) and two in S. cerevisiae (Gtr1 and Gtr2) (Schürmann et al, 1995; Hirose et al, 1998; Sekiguchi et al, 2001). Mammalian RAGs localize to the lysosome irrespective of amino acid availability, by interacting with the lysosomal pentameric complex RAGULATOR (Sancak et al, 2010; Bar‐Peled et al, 2012). In yeast, the EGO (Ego1–Ego2–Ego3) ternary complex, the ortholog of RAGULATOR, tethers Gtr1/2 to the vacuole (the yeast equivalent of the lysosome) (Kogan et al, 2010; Zhang et al, 2012; Levine et al, 2013; Powis et al, 2015). RAGs function as heterodimers in which RAGA or RAGB dimerizes with RAGC or RAGD, and Gtr1 dimerizes with Gtr2 (Nakashima et al, 1999; Sekiguchi et al, 2001). Amino acid sufficiency promotes the active conformation of the RAG heterodimer in which RAGA/B or Gtr1 is loaded with GTP, and RAGC/D or Gtr2 is loaded with GDP (Kim et al, 2008; Sancak et al, 2008; Binda et al, 2009; Fig 1). In mammals, the active RAG heterodimer binds RAPTOR and thereby recruits mTORC1 to the lysosome (Sancak et al, 2008). Once on the lysosome, the growth factor‐stimulated GTP‐loaded form of the small GTPase RHEB (RAS homolog enriched in brain) binds and activates mTORC1 (Long et al, 2005). Growth factors stimulate lysosomal RHEB through the PI3K‐PDK1‐AKT pathway (reviewed in Pearce et al, 2010; Dibble & Cantley, 2015). AKT phosphorylates and inactivates TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 2) by inducing its release from the lysosome (Inoki et al, 2002; Manning et al, 2002; Menon et al, 2014). TSC2 otherwise associates with TSC1 and TBC1D7 to form the TSC complex that functions as GAP (GTPase‐activating protein) toward lysosomal RHEB (Gao et al, 2002; Kenerson et al, 2002; Kwiatkowski et al, 2002; Onda et al, 2002; Tee et al, 2002; Garami et al, 2003; Inoki et al, 2003a; Dibble et al, 2012). Thus, full activation of mTORC1 requires input from amino acids and growth factors. In budding yeast, the active Gtr1GTP–Gtr2GDP heterodimer similarly binds Kog1 to stimulate TORC1, but via a mechanism that possibly differs from that of mammals since (i) yeast TORC1 is constitutively localized to the limiting membrane of the vacuole or to discrete perivacuolar sites irrespective of the presence or absence of leucine (Binda et al, 2009) or a nitrogen source (Kira et al, 2014, 2015; Hughes Hallett et al, 2015), and (ii) budding yeast does not express TSC or RHEB orthologs. We note that yeast contains a protein, termed Rhb1 (Urano et al, 2000), that resembles RHEB, but is not a functional RHEB homolog.

Figure 1. Regulation of TORC1 by amino acids in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and mammals.

Proteins shown in green promote TORC1 activation. Proteins in red inhibit TORC1. GAP and GEF between parentheses indicate that the proteins act as GTPase‐activating proteins or guanine exchange factors, respectively. Dashed lines indicate indirect interactions. There is no evidence that the yeast RHEB‐related protein Rhb1 plays a role in TORC1 regulation. See main text for details.

mTORC1 inactivation is an active process that requires translocation of TSC2 to the lysosome to inhibit RHEB upon growth factor deprivation (Menon et al, 2014; Fawal et al, 2015; Demetriades et al, 2016), amino acid deprivation (Demetriades et al, 2014; Deng et al, 2015), or other stress conditions (e.g., hypoxia or osmotic stress) (Plescher et al, 2015; Demetriades et al, 2016). It has been proposed that the “inactive” RAGA/BGDP–RAGC/DGTP heterodimer recruits TSC2 to the lysosome in amino acid‐starved cells (Demetriades et al, 2014). However, two studies have concluded that amino acids do not regulate lysosomal localization of TSC2 (Menon et al, 2014; Fawal et al, 2015). This discrepancy is likely due to differences in cell types and experimental conditions (Demetriades et al, 2016). The inactive GDP‐loaded version of Gtr1 has been reported to inhibit TORC1 activity and growth via the non‐essential TORC1 component Tco89 (Binda et al, 2009).

The nucleotide binding status of the mammalian RAGs and yeast Gtr1/2 is tightly regulated by conserved GAPs and GEFs (guanine exchange factors) (for review, see Shimobayashi & Hall, 2015; Powis & De Virgilio, 2016; Fig 1). RAGULATOR, besides serving as a scaffold for the RAGs, has GEF activity toward RAGA/B (Bar‐Peled et al, 2012). In yeast, rather than the EGO complex, the vacuolar protein Vam6 has been proposed to be the GEF for Gtr1 (Binda et al, 2009). The heterotrimeric protein complexes GATOR1 (GAP activity toward RAGs 1) and SEACIT (Seh1‐associated subcomplex inhibiting TORC1) function as GAPs for RAGA/B and Gtr1, respectively. GATOR1 is composed of DEPDC5 (DEP domain‐containing protein 5), NPRL2 (nitrogen permease regulator 2‐like protein), and NPRL3 where DEPDC5 is thought to possess the GAP activity toward RAGA/B (Bar‐Peled et al, 2013; Panchaud et al, 2013a). SEACIT is composed of Npr2, Npr3, and the catalytic subunit Iml1 (Panchaud et al, 2013a). The mammalian pentameric complex GATOR2, consisting of SEC13 (protein SEC13 homolog), SEH1L (nucleoporin SEH1), WDR24 (WD repeat‐containing protein 24), WDR59, and MIOS (WD repeat‐containing protein MIO), and the yeast SEACAT (Seh1‐associated complex subcomplex activating TORC1), consisting of Sec13, Seh1, Sea2, Sea3, and Sea4, bind and negatively regulate GATOR1 and SEACIT, respectively, via an undefined mechanism (Bar‐Peled et al, 2013; Panchaud et al, 2013b; Dokudovskaya & Rout, 2015). Mammalian FLCN (folliculin) and its binding partners FNIP1 and 2 (folliculin‐interacting proteins 1 and 2) as well as their yeast orthologs Lst4 and Lst7 are the GAPs for RAGC/D (Petit et al, 2013; Tsun et al, 2013) and Gtr2 (Péli‐Gulli et al, 2015), respectively. The identity of the GEF for RAGC/D and Gtr2 remains unknown. Two independent studies recently demonstrated that amino acids regulate RAGA activity via ubiquitination (Deng et al, 2015; Jin et al, 2015).

Amino acid sensing and signaling to TORC1

Amino acids modulate the guanine nucleotide binding status of RAG/Gtr and eventually TORC1 activity. How amino acid sufficiency is sensed and signaled to RAGs are long‐standing questions. Several mechanisms have been proposed, including amino acids being sensed in the cytosol, lysosome, and mitochondria. How many different amino acids are actually sensed remains unknown. mTORC1 activity is particularly sensitive to leucine and arginine levels (Hara et al, 1998), whereas yeast TORC1 responds best to the amino acid and nitrogen source glutamine (Godard et al, 2007; Stracka et al, 2014).

Leucine and glutamine sensing mechanisms

SESTRIN1 through 3 are stress‐responsive proteins that mediate metabolic homeostasis in metazoans (for a review, see Lee et al, 2013). SESTRINS have been proposed to repress mTORC1 through at least three different mechanisms: (i) by activating AMPK (AMP‐activated protein kinase) and the TSC complex (Budanov & Karin, 2008), (ii) by acting as a GDI (guanosine dissociation inhibitor) to prevent GDP dissociation from RAGA/B (Peng et al, 2014), and (iii) by binding and inhibiting GATOR2 to prevent mTORC1 lysosomal localization in response to amino acids (Chantranupong et al, 2014; Parmigiani et al, 2014; Kim et al, 2015b). Recently, Wolfson et al (2016) demonstrated that the cytoplasmic protein SESTRIN2 directly binds leucine in vitro. Leucine fails to stimulate mTORC1 in cells expressing a leucine binding‐deficient mutant of SESTRIN2. Leucine (also isoleucine, methionine, and less potently, valine) disrupts the interaction between SESTRIN2 and GATOR2 in vitro and in cells. In cells starved for leucine, SESTRIN2 binds and inhibits GATOR2. Leucine deprivation fails to inhibit mTORC1 in SESTRIN‐depleted cells expressing a GATOR2 binding‐deficient mutant of SESTRIN2, indicating that SESTRIN2 controls mTORC1 via GATOR2. Upon leucine binding, SESTRIN2 dissociates from GATOR2, which results in mTORC1 translocation to the lysosome (Wolfson et al, 2016). Thus, Wolfson et al proposed that SESTRIN2 is almost certainly a cytosolic leucine sensor that acts upstream GATOR2 (Wolfson et al, 2016) (Fig 1). However, the role of SESTRINS as leucine sensors has been questioned, as SESTRINS can inhibit mTORC1 in cells growing in medium containing leucine (see Lee et al, 2016 and references therein). Recently, Saxton et al (2016c) resolved the structure of SESTRIN2 bound to leucine, and identified the leucine binding pocket and the GATOR2 binding site. They suggest that leucine promotes a conformational change in SESTRIN2 that alters the GATOR2 binding site, thereby causing dissociation of SESTRIN2 from GATOR2 (Saxton et al, 2016c). Kim et al recently reported a crystal structure of SESTRIN2 obtained without the addition of exogenous leucine (Kim et al, 2015a). This structure is largely identical to the one generated by Saxton et al in the presence of leucine, suggesting that leucine binding does not induce a significant conformational change in SESTRIN2 (Lee et al, 2016). However, the apo‐SESTRIN2 crystal structure presented by Kim et al possibly contains leucine (Saxton et al, 2016b). Thus, more studies are required to elucidate how leucine binding affects the conformation of SESTRIN2 to induce its dissociation from GATOR2 and how the SESTRIN2–GATOR2 interaction affects GATOR1 and RAGs. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether additional factors regulate the dissociation of leucine from SESTRIN2 upon leucine starvation.

In budding yeast, leucine activates TORC1 via Gtr1 (Binda et al, 2009), although it is unknown whether leucine signals to Gtr1 through SEACAT. Yeast lacks SESTRIN orthologs, suggesting that functional counterparts of SESTRINS exist or that yeast and mammalian cells sense leucine differently. Two studies demonstrated that yeast and mammalian leucyl‐tRNA synthetases (LeuRS) act as cytoplasmic leucine sensors to activate TORC1/mTORC1, although via different mechanisms (Bonfils et al, 2012; Han et al, 2012; Fig 1). Bonfils et al demonstrated that yeast leucine‐bound LeuRS binds Gtr1, and suggested that this interaction is necessary and sufficient to mediate leucine signaling to TORC1. Han et al (2012) reported that mammalian LeuRS senses leucine to induce lysosomal localization and activity of mTORC1. This study also suggested that LeuRS has GAP activity toward RAGD. The role of LeuRS as a GAP, however, has been questioned (Tsun et al, 2013). Yoon et al (2016) recently showed that LeuRS is part of a RAG‐independent mechanism by which amino acid sufficiency activates mTORC1. This mechanism involves the class III PI‐3‐kinase VPS34 and PLD1 (phospholipase D1; Yoon et al, 2011). Further studies are required to reconcile the RAG‐dependent and RAG‐independent roles of LeuRS as an mTORC1 regulator.

Consistent with leucine sensing regulating mTORC1 activity, plasma membrane leucine (SLC7A5–SLC3A2) and glutamine (SLC1A5) transporters affect mTORC1 signaling (reviewed in Taylor, 2014). Cytosolic glutamine is used as an anti‐solute to import leucine via the SLC7A5–SLC3A2 heterodimeric antiporter. Decreased leucine import due to the loss of SLC1A5 or SLC7A5–SLC3A2 impairs mTORC1 activity, indicating that glutamine acts upstream of leucine as an efflux solute to increase cytosolic leucine levels and activate mTORC1 (Nicklin et al, 2009). A recent study demonstrated that overexpression of LAPTM4b (lysosomal protein transmembrane 4 beta) recruits SLC7A5–SLC3A2 to the lysosome, thereby increasing leucine accumulation in the lysosome. Knockdown of LAPTM4b reduces mTORC1 activity in cells stimulated with leucine (Milkereit et al, 2015), indicating that leucine sensing occurs at lysosomes. Pharmacological inhibition of SLC1A5 also reduces mTORC1 activity in triple‐negative basal‐like breast cancer cells (Van Geldermalsen et al, 2016).

Glutaminolysis, the double deamination of glutamine to produce α‐ketoglutarate, provides a mechanism for leucine and glutamine sensing in mitochondria (Durán et al, 2012). GLS (glutaminase) catalyzes the deamination of glutamine to yield glutamate. GDH (glutamate dehydrogenase), which requires leucine as a cofactor, then converts glutamate to α‐ketoglutarate. α‐Ketoglutarate activates RAG‐mTORC1 through PHD (prolyl hydroxylase) (Durán et al, 2012, 2013). Thus, in mammalian cells, leucine and glutamine activate mTORC1 via glutaminolysis and α‐ketoglutarate production upstream of RAG (Fig 1). PHDs are conserved from yeast to mammals. It would be of interest to determine whether the budding yeast putative prolyl‐4‐hydroxylase Tpa1 (Henri et al, 2010) regulates TORC1.

Glutamine activates TORC1 also independently of the RAGs/Gtr1/2, in yeast and mammals. Stracka et al (2014) demonstrated that glutamine activates TORC1 in yeast cells lacking Gtr1 or Vam6. Although the Gtr1‐independent mechanism of TORC1 activation remains elusive, genetic experiments suggest that it could involve the vacuolar membrane‐associated phosphatidylinositol 3‐phosphate binding protein Pib2 (Kim & Cunningham, 2015). Consistent with the observations reported in yeast, glutamine stimulates lysosomal translocation and activation of mTORC1 in a RAGA/B and RAGULATOR‐independent manner via the small GTPase ARF1 (ADP‐ribosylation factor 1) and v‐ATPase (vacuolar ATPase; Jewell et al, 2015; Fig 1). How ARF1 senses glutamine and regulates mTORC1 is unclear.

Arginine sensing mechanisms

The lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 has been proposed as an arginine sensor upstream of mTORC1. SLC38A9 binds RAGULATOR and RAGs, and knockdown of SLC38A9 impairs arginine‐induced activation of mTORC1 (Jung et al, 2015; Rebsamen et al, 2015; Wang et al, 2015; Fig 1). The yeast vacuolar amino acid transporters Avt1‐7 (Russnak et al, 2001) are the transporters most closely related to SLC38A9. Whether Avt proteins regulate TORC1 activity requires further investigation.

Recently, Chantranupong et al (2016) identified the GATOR2‐interacting protein CASTOR1 (cellular arginine sensor for mTORC1) as a cytoplasmic arginine sensor upstream of mTORC1. CASTOR1 forms homodimers or, with the highly related protein CASTOR2, heterodimers. CASTOR1 homodimers or CASTOR1–CASTOR2 heterodimers directly bind arginine in vitro. Arginine binding disrupts the interaction of CASTOR dimers with GATOR2, presumably allowing free GATOR2 to inhibit GATOR1 and thereby activate mTORC1. Arginine fails to stimulate mTORC1 activity in cells expressing an arginine binding‐deficient mutant of CASTOR1. Thus, binding of arginine to CASTOR1 enables GATOR2 to enhance mTORC1 activity (Fig 1). The crystal structure of CASTOR1 in complex with arginine, reported by two independent groups, illustrates in detail the arginine binding pocket of CASTOR1 (Saxton et al, 2016a; Xia et al, 2016). Furthermore, Saxton et al (2016a) identified several residues in CASTOR1 required for interaction with GATOR2, and speculated that arginine binding transmits an allosteric signal to trigger dissociation of CASTOR dimers from GATOR2. The structure of apo‐CASTOR1 or the CASTOR1–GATOR2 complex would contribute to understanding this mechanism. In addition, it would be of interest to investigate if and how CASTOR1 and SESTRIN2 bind GATOR2 simultaneously in cells starved for arginine and leucine. CASTOR homologs are present in vertebrates, but are absent in worms, flies, and yeast. How arginine is sensed in non‐vertebrates remains to be clarified.

Based on genetic experiments, it has been suggested that CASTOR1 and SLC38A9 regulate mTORC1 activation by arginine via parallel mechanisms (Chantranupong et al, 2016). However, it appears that CASTOR1 is the more important regulator of the two since mTORC1 is essentially fully active in arginine‐starved, CASTOR1‐knockout cells. Furthermore, additional regulators may exist since arginine slightly activates mTORC1 in SLC38A9‐knockout CASTOR1‐knockdown cells. Curiously, Carroll et al (2016) recently reported that arginine cooperates with growth factors to prevent the interaction between TSC2 and RHEB at the lysosome, and thereby to activate mTORC1.

Methionine sensing mechanism

It has been proposed that in yeast cells utilizing lactate as carbon source, methionine signals to Gtr1/2 through synthesis of the methyl donor SAM (S‐adenosylmethionine). SAM promotes Ppm1‐mediated methylation of the catalytic subunit of the type 2A protein phosphatase (PP2A). Methylated PP2A dephosphorylates the SEACIT complex component Npr2 to prevent assembly of the complex and eventually to activate TORC1 (Sutter et al, 2013; Fig 1).

Amino acid sensing in the lysosome

It has also been suggested that amino acid levels are sensed in the lysosome. Zoncu et al (2011) proposed that mTORC1 senses amino acids in the lumen of the lysosome through an “inside‐out” mechanism that requires the v‐ATPase. According to this model, amino acids in the lumen of the lysosome signal to the RAGs via v‐ATPase and RAGULATOR. Whether the yeast v‐ATPase mediates amino acid signaling toward Gtr1/2 is unknown (Fig 1).

SLC15A4 is a lysosomal proton‐coupled histidine transporter, which exports histidine from the lysosome to the cytoplasm. SLC15A4 is preferentially expressed in immune cells, including dendritic and B cells. SLC15A4‐depleted B cells accumulate histidine in the lysosome and display increased lysosomal pH, impaired v‐ATPase function, and reduced mTORC1 activity (Kobayashi et al, 2014). SLC15A4 may affect mTORC1 activity through v‐ATPase although the mechanism remains elusive.

The proton and amino acid symporter PAT1/SLC36A1 is required for mTORC1 activation by amino acids (Heublein et al, 2010). PAT1/SLC36A1 is located mainly in endosomal compartments and can potentially export amino acids to the cytoplasm. PAT1/SLC36A1 physically interacts with RAGC/D. Knockdown of PAT1 reduces the amino acid‐stimulated translocation of mTORC1 to the lysosome (Ögmundsdóttir et al, 2012).

Amino acid sensing in the Golgi

Thomas et al (2014) reported that mTORC1 on the Golgi can be activated by amino acids in a RAG‐independent manner. Mechanistically, amino acids promote GTP loading of the small GTPase RAB1A (Ras‐related protein RAB‐1A) which in turn stimulates mTORC1 interaction with Golgi‐resident RHEB (Thomas et al, 2014). The proton and amino acid symporter PAT4/SLC36A4 is required for mTORC1 activation by amino acids (Heublein et al, 2010). PAT4/SLC36A4 is mainly localized to the Golgi where it physically interacts with mTOR, RAPTOR, and RAB1A (Fan et al, 2016). Ypt7, the yeast RAB1A ortholog, is also required for amino acids to activate TORC1 (Thomas et al, 2014), indicating that amino acid sensing could occur at the Golgi in both mammals and yeast.

Extracellular amino acid sensing

The G protein‐coupled receptor T1R1/T1R3 is an amino acid receptor originally discovered in gustatory neurons as a detector of the umami (glutamate) flavor (Matsunami et al, 2000; Nelson et al, 2002). Knockdown of T1R1/T1R3 impairs amino acid‐induced mTORC1 lysosomal translocation and activation without significantly affecting intracellular amino acid levels (Wauson et al, 2012). This study suggests that extracellular amino acid availability could be sufficient to modulate mTORC1 activity.

The GAAC signaling pathway

The conserved GAAC (general amino acid control) signaling pathway coordinates amino acid availability with translation initiation to allow cells to adapt to amino acid starvation (reviewed in Hinnebusch, 2005). The GAAC signaling pathway senses the absence of amino acids via uncharged tRNAs that accumulate when free amino acid levels are low. In amino acid‐starved cells, uncharged tRNAs bind and activate the protein kinase GCN2 (general control non‐derepressible 2; Wek et al, 1989, 1995; Diallinas & Thireos, 1994; Dong et al, 2000; Narasimhan et al, 2004). Active GCN2 phosphorylates the alpha subunit of eIF2 (eukaryotic initiation factor 2α), thereby inhibiting eIF2 and ultimately leading to a general repression of mRNA translation (Dever et al, 1992). Paradoxically, this favors selective translation of mRNA with a unique 5′UTR structure containing short uORFs (upstream open reading frames). The uORF containing mRNA encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor termed ATF4 (activating transcription factor 4) in mammals (Harding et al, 2000; Vattem & Wek, 2004) and Gcn4 in yeast (Hinnebusch, 1984). ATF4/Gcn4 induces the expression of amino acid transporters, enzymes involved in amino acid metabolism (Hinnebusch & Natarajan, 2002; Siu et al, 2002; Averous et al, 2004; Hinnebusch, 2005; Kilberg et al, 2009; Staschke et al, 2010), and factors involved in autophagy (B'chir et al, 2013; Fig 2), thereby allowing adaptation to amino acid starvation.

Figure 2. Crosstalk between TORC1 and GAAC signaling pathways in yeast and mammals.

Proteins shown in green promote Gcn4/ATF4‐dependent transcription. Proteins in red inhibit Gcn4/ATF4‐dependent transcription. PPase, protein phosphatase. See main text for details.

The potential crosstalk between GAAC and mTORC1 has not been studied in detail, although inhibition of hepatic mTORC1 in mice fed a leucine‐free diet or in cells starved for leucine requires GCN2 (Anthony et al, 2004; Xiao et al, 2011). Recently, two independent studies confirmed that mTORC1 inhibition in response to amino acid deprivation requires GCN2 (Ye et al, 2015; Averous et al, 2016). Averous et al (2016) proposed that, upon short‐term (0.5 to 1 h) deprivation of leucine or arginine, GCN2 inhibits mTORC1 via an uncharacterized ATF4‐independent mechanism (Fig 2). Short‐term deprivation of leucine also requires phosphorylated eIF2α to inhibit mTORC1. Ye et al reported that, upon long‐term (24 h) deprivation of leucine, arginine, or glutamine, GCN2 inhibits mTORC1 through ATF4‐mediated induction of SESTRIN2 expression. SESTRIN2 in turn inhibits mTORC1 in a RAGA/B‐dependent manner (Ye et al, 2015) (Fig 2). The findings by Ye et al imply that SESTRIN2 inhibits mTORC1 even in the presence of leucine. It would be of interest to determine whether SESTRIN2‐mediated inhibition of mTORC1 requires GATOR2 and whether leucine‐binding ability of SESTRIN2 is required to inhibit mTORC1 under these conditions.

A link between TORC1 and GAAC has been demonstrated in S. cerevisiae. TORC1 prevents dephosphorylation of Ser577 in Gcn2 by inhibiting one or more phosphatases. Phosphorylation of Gcn2 at Ser577 inhibits Gcn2 by decreasing its uncharged tRNA binding ability (Cherkasova & Hinnebusch, 2003; Kubota et al, 2003). Thus, in budding yeast, Gcn2 activation upon amino acid starvation is a consequence of an increase in uncharged tRNAs and the release of an inhibitory effect of TORC1 (Fig 2). Despite the conserved role of Gcn2 in translation, it is unknown whether mTORC1 regulates GCN2. Interestingly, a recent report showed that mTORC1 stimulates purine synthesis through ATF4 activation independent of eIF2α phosphorylation (Ben‐Sahra et al, 2016). Further studies are required to better understand how GAAC and TORC1 signaling pathways coordinate to allow cells to adapt to changes in nutrient availability.

The yeast SPS amino acid sensing pathway

The SPS pathway senses amino acid availability and regulates amino acid uptake (reviewed in Ljungdahl, 2009; Ljungdahl & Daignan‐Fornier, 2012). The SPS pathway is present only in fungi (Martínez & Ljungdahl, 2005). In contrast to the GAAC pathway, the SPS pathway is activated by amino acids. The primary amino acid sensor is a plasma membrane‐localized complex composed of Ssy1, Ptr3, and Ssy5 (named as SPS sensor) (Forsberg & Ljungdahl, 2001). Ssy1 is a multi‐spanning transmembrane sensor structurally related to amino acid permeases but lacking transporting capacity (Didion et al, 1998; Iraqui et al, 1999; Klasson et al, 1999). Ssy1 possesses an exclusively cytoplasmic N‐terminal domain, which binds the scaffold protein Ptr3, and the endoprotease Ssy5. Ssy5 is expressed as a zymogen composed of a catalytic domain attached to an inhibitory domain (Abdel‐Sater et al, 2004a; Andréasson et al, 2006; Poulsen et al, 2006). Binding of extracellular amino acids to exposed Ssy1 induces a conformational change that stimulates the phosphorylation and ubiquitin‐mediated degradation of the inhibitory domain of Ssy5 (Pfirrmann et al, 2010; Omnus et al, 2011). Active Ssy5 cleaves the N‐terminal cytoplasmic retention motif of the transcription factors Stp1 and 2 (Andréasson & Ljungdahl, 2002). Processed Stp1/2 translocates into the nucleus to induce the expression of genes encoding amino acid permeases (Abdel‐Sater et al, 2004b; Boban & Ljungdahl, 2007). The SPS pathway and TORC1 are interconnected. TORC1, via the PP2A‐like phosphatase Sit4, promotes the stability of nuclear Stp1 and thus amino acid uptake (Shin et al, 2009).

Glucose sensing and signaling to TORC1

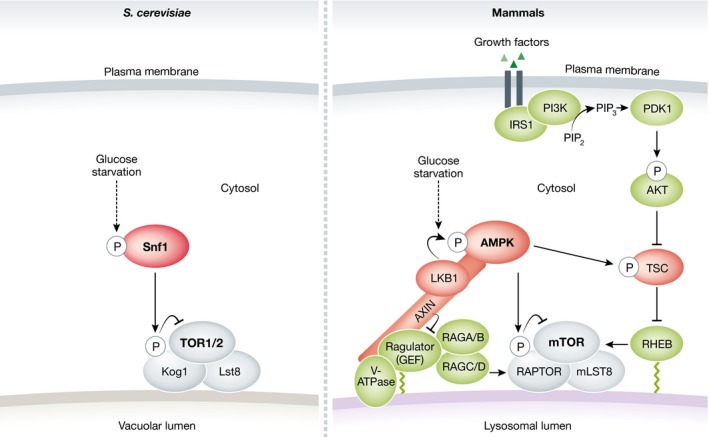

AMPK is a conserved sensor of cellular energy status. It is activated by metabolic stress, such as glucose deprivation, that increases cellular ADP/ATP and AMP/ATP ratios (reviewed in Hardie, 2007; Hardie et al, 2012). AMPK promotes catabolic processes such as autophagy and inhibits anabolic processes such as protein synthesis, in part by negatively regulating TORC1 signaling (for review, see Hardie, 2014; Hindupur et al, 2015). In mammals, AMPK inhibits mTORC1 via at least two different mechanisms (Fig 3): (i) AMPK phosphorylates and activates TSC2, thereby inactivating RHEB (Inoki et al, 2003b), and (ii) AMPK phosphorylates RAPTOR on Ser722 and Ser792 to inhibit mTORC1 (Gwinn et al, 2008). Although budding yeast does not express TSC2, the AMPK Snf1 is required for TORC1 inactivation in glucose‐starved cells (Hughes Hallett et al, 2014). Active Snf1 phosphorylates Kog1 at Ser491 and Ser494. Curiously, phosphorylated Kog1 dissociates from TORC1 and translocates to discrete perivacuolar sites, leading to a reduction in TORC1 activity (Hughes Hallett et al, 2015). The Snf1 phosphorylation sites in Kog1 are located in a glutamine‐rich, prion‐like motif. This motif and a similar motif, separated by 300 residues, are essential for Kog1 translocation to perivacuolar sites upon glucose deprivation (Fig 3). Interestingly, organisms that express Kog1/RAPTOR proteins containing prion‐like motifs (e.g., S. cerevisiae and C. elegans) lack TSC orthologs, whereas species lacking such motifs in Kog1/RAPTOR (e.g., fission yeast, flies, and mammals) express TSC proteins. Thus, mechanisms by which AMPK inhibits TORC1 may have diverged during evolution.

Figure 3. Crosstalk between TORC1 and AMPK signaling pathways in yeast and mammals.

Proteins shown in green promote TORC1 activation. Proteins in red inhibit TORC1. IRS1, insulin receptor substrate 1. See main text for details.

Glucose deprivation inhibits TORC1 in yeast cells expressing constitutively active versions of Gtr1 and Gtr2 (Gtr1GTP–Gtr2GDP) (Hughes Hallett et al, 2015), suggesting that TORC1 inhibition upon glucose starvation does not require Gtr1/2. In contrast, Efeyan et al (2014) reported that glucose deprivation fails to inhibit mTORC1 in primary MEFs expressing a constitutively active form of RAGA (RAGAGTP), indicating that RAGs may signal glucose sufficiency to mTORC1. In this regard, Zhang et al reported that AXIN (axis inhibition protein 1), originally discovered as an inhibitor of WNT signaling (Zeng et al, 1997), is required for AMPK activation by its upstream kinase LKB1 (liver kinase B1) at the lysosomal surface (Zhang et al, 2013). A subsequent study demonstrated that, upon glucose starvation, AXIN/LKB1 promotes AMPK phosphorylation and activation at the lysosomal surface via v‐ATPase‐RAGULATOR. Concurrently, AXIN inhibits GEF activity of RAGULATOR toward RAGA/B, thereby inactivating mTORC1 (Zhang et al, 2014) (Fig 3). These observations provide an explanation for how glucose availability is transduced to RAGs and suggest that the lysosomal surface may represent a key platform where nutrients are sensed in a reciprocal manner by mTORC1 and AMPK. A better understanding of the interplay between TORC1 and AMPK in coordinating nutrient‐sensing pathways in yeast and mammals will provide new insights into the regulation of cellular metabolism.

Concluding remarks and future directions

Although it has long been known that TORC1 promotes cell growth in response to nutrients (Barbet et al, 1996) and that amino acids activate mTORC1 (Hara et al, 1998), the identity of amino acid sensors upstream of TORC1 has started to emerge only recently. Amino acid sufficiency regulates TORC1 via different RAG/Gtr‐dependent and RAG/Gtr‐independent mechanisms. The RAGs, as well as their upstream regulators, are largely conserved from yeast to mammals. Intriguingly, the recently identified mammalian cytosolic leucine and arginine sensors seem to lack yeast counterparts although they impinge on GATOR2 that does have a counterpart in yeast. The reason for this is unclear and follow‐up studies are required to elucidate if and how amino acids regulate the yeast GATOR2 ortholog SEACAT.

Finally, mutations affecting mammalian amino acid sensing components are linked to immunodeficiency, epilepsy, and cancer (Shimobayashi & Hall, 2015), and mTOR is often deregulated in metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes, and cancer (Efeyan et al, 2012; Liko & Hall, 2015). A better understanding of how nutrient availability is transduced to TOR may allow novel therapies against mTOR‐related diseases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the Louis Jeantet Foundation, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the European Research Council, SystemsX.ch, and the Canton of Basel.

The EMBO Journal (2017) 36: 397–408

References

- Abdel‐Sater F, El Bakkoury M, Urrestarazu A, Vissers S, André B (2004a) Amino acid signaling in yeast: casein kinase I and the Ssy5 endoprotease are key determinants of endoproteolytic activation of the membrane‐bound Stp1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol 24: 9771–9785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel‐Sater F, Iraqui I, Urrestarazu A, André B (2004b) The external amino acid signaling pathway promotes activation of Stp1 and Uga35/Dal81 transcription factors for induction of the AGP1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics 166: 1727–1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andréasson C, Ljungdahl PO (2002) Receptor‐mediated endoproteolytic activation of two transcription factors in yeast. Genes Dev 16: 3158–3172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andréasson C, Heessen S, Ljungdahl PO (2006) Regulation of transcription factor latency by receptor‐activated proteolysis. Genes Dev 20: 1563–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony TG, McDaniel BJ, Byerley RL, McGrath BC, Cavener DR, McNurlan MA, Wek RC (2004) Preservation of liver protein synthesis during dietary leucine deprivation occurs at the expense of skeletal muscle mass in mice deleted for eIF2 kinase GCN2. J Biol Chem 279: 36553–36561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averous J, Bruhat A, Jousse C, Carraro V, Thiel G, Fafournoux P (2004) Induction of CHOP expression by amino acid limitation requires both ATF4 expression and ATF2 phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 279: 5288–5297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averous J, Lambert‐Langlais S, Mesclon F, Carraro V, Parry L, Jousse C, Bruhat A, Maurin A‐C, Pierre P, Proud CG, Fafournoux P (2016) GCN2 contributes to mTORC1 inhibition by leucine deprivation through an ATF4 independent mechanism. Sci Rep 6: 27698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet NC, Schneider U, Helliwell SB, Stansfield I, Tuite MF, Hall MN (1996) TOR controls translation initiation and early G1 progression in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 7: 25–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar‐Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM (2012) Ragulator is a GEF for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Cell 150: 1196–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar‐Peled L, Chantranupong L, Cherniack AD, Chen WW, Ottina KA, Grabiner BC, Spear ED, Carter SL, Meyerson M, Sabatini DM (2013) A tumor suppressor complex with GAP activity for the Rag GTPases that signal amino acid sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 340: 1100–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar‐Peled L, Sabatini DM (2014) Regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. Trends Cell Biol 24: 400–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- B'chir W, Maurin A‐C, Carraro V, Averous J, Jousse C, Muranishi Y, Parry L, Stepien G, Fafournoux P, Bruhat A (2013) The eIF2α/ATF4 pathway is essential for stress‐induced autophagy gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 7683–7699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Sahra I, Hoxhaj G, Ricoult SJH, Asara JM, Manning BD (2016) mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science 351: 728–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda M, Péli‐Gulli M‐P, Bonfils G, Panchaud N, Urban J, Sturgill TW, Loewith R, De Virgilio C (2009) The Vam6 GEF controls TORC1 by activating the EGO complex. Mol Cell 35: 563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boban M, Ljungdahl PO (2007) Dal81 enhances Stp1‐ and Stp2‐dependent transcription necessitating negative modulation by inner nuclear membrane protein Asi1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics 176: 2087–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfils G, Jaquenoud M, Bontron S, Ostrowicz C, Ungermann C, De Virgilio C (2012) Leucyl‐tRNA synthetase controls TORC1 via the EGO complex. Mol Cell 46: 105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Albers MW, Bum Shin T, ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL (1994) A mammalian protein targeted by G1‐arresting rapamycin–receptor complex. Nature 369: 756–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budanov AV, Karin M (2008) p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell 134: 451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll B, Maetzel D, Maddocks ODK, Otten G, Ratcliff M, Smith GR, Dunlop EA, Passos JF, Davies OR, Jaenisch R, Tee AR, Sarkar S, Korolchuk VI (2016) Control of TSC2‐Rheb signaling axis by arginine regulates mTORC1 activity. Elife 5: e11058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantranupong L, Wolfson RL, Orozco JM, Saxton RA, Scaria SM, Bar‐Peled L, Spooner E, Isasa M, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM (2014) The Sestrins interact with GATOR2 to negatively regulate the amino‐acid‐sensing pathway upstream of mTORC1. Cell Rep 9: 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantranupong L, Scaria SM, Saxton RA, Gygi MP, Shen K, Wyant GA, Wang T, Harper JW, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM (2016) The CASTOR proteins are arginine sensors for the mTORC1 pathway. Cell 165: 153–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkasova VA, Hinnebusch AG (2003) Translational control by TOR and TAP42 through dephosphorylation of eIF2alpha kinase GCN2. Genes Dev 17: 859–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu MI, Katz H, Berlin V (1994) RAPT1, a mammalian homolog of yeast Tor, interacts with the FKBP12/rapamycin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 12574–12578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriades C, Doumpas N, Teleman AA (2014) Regulation of TORC1 in response to amino acid starvation via lysosomal recruitment of TSC2. Cell 156: 786–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriades C, Plescher M, Teleman AA (2016) Lysosomal recruitment of TSC2 is a universal response to cellular stress. Nat Commun 7: 10662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Jiang C, Chen L, Jin J, Wei J, Zhao L, Chen M, Pan W, Xu Y, Chu H, Wang X, Ge X, Li D, Liao L, Liu M, Li L, Wang P (2015) The ubiquitination of RagA GTPase by RNF152 negatively regulates mTORC1 activation. Mol Cell 58: 804–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever TE, Feng L, Wek RC, Cigan AM, Donahue TF, Hinnebusch AG (1992) Phosphorylation of initiation factor 2 alpha by protein kinase GCN2 mediates gene‐specific translational control of GCN4 in yeast. Cell 68: 585–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallinas G, Thireos G (1994) Genetic and biochemical evidence for yeast GCN2 protein kinase polymerization. Gene 143: 21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibble CC, Elis W, Menon S, Qin W, Klekota J, Asara JM, Finan PM, Kwiatkowski DJ, Murphy LO, Manning BD (2012) TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1‐TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol Cell 47: 535–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibble CC, Cantley LC (2015) Regulation of mTORC1 by PI3K signaling. Trends Cell Biol 25: 545–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didion T, Regenberg B, Jørgensen MU, Kielland‐Brandt MC, Andersen HA (1998) The permease homologue Ssy1p controls the expression of amino acid and peptide transporter genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Microbiol 27: 643–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokudovskaya S, Rout MP (2015) SEA you later alli‐GATOR – a dynamic regulator of the TORC1 stress response pathway. J Cell Sci 128: 2219–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Qiu H, Garcia‐Barrio M, Anderson J, Hinnebusch AG (2000) Uncharged tRNA activates GCN2 by displacing the protein kinase moiety from a bipartite tRNA‐binding domain. Mol Cell 6: 269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán RV, Oppliger W, Robitaille AM, Heiserich L, Skendaj R, Gottlieb E, Hall MN (2012) Glutaminolysis activates Rag‐mTORC1 signaling. Mol Cell 47: 349–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán RV, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Frezza C, Heiserich L, Tardito S, Bussolati O, Rocha S, Hall MN, Gottlieb E (2013) HIF‐independent role of prolyl hydroxylases in the cellular response to amino acids. Oncogene 32: 4549–4556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM (2012) Amino acids and mTORC1: from lysosomes to disease. Trends Mol Med 18: 524–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efeyan A, Schweitzer LD, Bilate AM, Chang S, Kirak O, Lamming DW, Sabatini DM (2014) RagA, but not RagB, is essential for embryonic development and adult mice. Dev Cell 29: 321–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S‐J, Snell C, Turley H, Li J‐L, McCormick R, Perera SMW, Heublein S, Kazi S, Azad A, Wilson C, Harris AL, Goberdhan DCI (2016) PAT4 levels control amino‐acid sensitivity of rapamycin‐resistant mTORC1 from the Golgi and affect clinical outcome in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 35: 3004–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawal M‐A, Brandt M, Djouder N (2015) MCRS1 binds and couples Rheb to amino acid‐dependent mTORC1 activation. Dev Cell 33: 67–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg H, Ljungdahl PO (2001) Genetic and biochemical analysis of the yeast plasma membrane Ssy1p‐Ptr3p‐Ssy5p sensor of extracellular amino acids. Mol Cell Biol 21: 814–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, Hino O, Kobayashi T, Yeung RS, Ru B, Pan D (2002) Tsc tumour suppressor proteins antagonize amino‐acid‐TOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol 4: 699–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garami A, Zwartkruis FJT, Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Stocker H, Kozma SC, Hafen E, Bos JL, Thomas G (2003) Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E‐BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell 11: 1457–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godard P, Urrestarazu A, Vissers S, Kontos K, Bontempi G, van Helden J, André B (2007) Effect of 21 different nitrogen sources on global gene expression in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Cell Biol 27: 3065–3086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ (2008) AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell 30: 214–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JM, Jeong SJ, Park MC, Kim G, Kwon NH, Kim HK, Ha SH, Ryu SH, Kim S (2012) Leucyl‐tRNA synthetase is an intracellular leucine sensor for the mTORC1‐signaling pathway. Cell 149: 410–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Yonezawa K, Weng QP, Kozlowski MT, Belham C, Avruch J (1998) Amino acid sufficiency and mTOR regulate p70 S6 kinase and eIF‐4E BP1 through a common effector mechanism. J Biol Chem 273: 14484–14494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (2002) Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell 110: 177–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG (2007) AMP‐activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 774–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA (2012) AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 251–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG (2014) AMPK–sensing energy while talking to other signaling pathways. Cell Metab 20: 939–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D (2000) Regulated translation initiation controls stress‐induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell 6: 1099–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama R, De Virgilio C (2016) Unsolved mysteries of Rag GTPase signaling in yeast. Small GTPases 7: 239–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN (1991) Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science 253: 905–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henri J, Rispal D, Bayart E, van Tilbeurgh H, Séraphin B, Graille M (2010) Structural and functional insights into Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tpa1, a putative prolylhydroxylase influencing translation termination and transcription. J Biol Chem 285: 30767–30778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heublein S, Kazi S, Ogmundsdóttir MH, Attwood EV, Kala S, Boyd CAR, Wilson C, Goberdhan DCI (2010) Proton‐assisted amino‐acid transporters are conserved regulators of proliferation and amino‐acid‐dependent mTORC1 activation. Oncogene 29: 4068–4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindupur SK, González A, Hall MN (2015) The opposing actions of target of rapamycin and AMP‐activated protein kinase in cell growth control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a019141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG (1984) Evidence for translational regulation of the activator of general amino acid control in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 6442–6446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG, Natarajan K (2002) Gcn4p, a master regulator of gene expression, is controlled at multiple levels by diverse signals of starvation and stress. Eukaryot Cell 1: 22–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG (2005) Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol 59: 407–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose E, Nakashima N, Sekiguchi T, Nishimoto T (1998) RagA is a functional homologue of S. cerevisiae Gtr1p involved in the Ran/Gsp1‐GTPase pathway. J Cell Sci 111: 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell JJ, Ricoult SJH, Ben‐Sahra I, Manning BD (2013) A growing role for mTOR in promoting anabolic metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans 41: 906–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Hallett JE, Luo X, Capaldi AP (2014) State transitions in the TORC1 signaling pathway and information processing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics 198: 773–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Hallett JE, Luo X, Capaldi AP (2015) Snf1/AMPK promotes the formation of Kog1/Raptor‐bodies to increase the activation threshold of TORC1 in budding yeast. Elife 4: e09181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan K‐L (2002) TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol 4: 648–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan K‐L (2003a) Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev 17: 1829–1834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan K‐L (2003b) TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 115: 577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iraqui I, Vissers S, Bernard F, de Craene JO, Boles E, Urrestarazu A, André B (1999) Amino acid signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a permease‐like sensor of external amino acids and F‐Box protein Grr1p are required for transcriptional induction of the AGP1 gene, which encodes a broad‐specificity amino acid permease. Mol Cell Biol 19: 989–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan K‐L (2013) Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14: 133–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell JL, Kim YC, Russell RC, Yu F‐X, Park HW, Plouffe SW, Tagliabracci VS, Guan K‐L (2015) Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science 347: 194–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin G, Lee SW, Zhang X, Cai Z, Gao Y, Chou PC, Rezaeian AH, Han F, Wang CY, Yao JC, Gong Z, Chan CH, Huang CY, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH, Tu SH, Wu CH, Sarbassov DD, Ho YS, Lin HK (2015) Skp2‐mediated RagA ubiquitination elicits a negative feedback to prevent amino‐acid‐dependent mTORC1 hyperactivation by recruiting GATOR1. Mol Cell 58: 989–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Genau HM, Behrends C (2015) Amino acid‐dependent mTORC1 regulation by the lysosomal membrane protein SLC38A9. Mol Cell Biol 35: 2479–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenerson HL, Aicher LD, True LD, Yeung RS (2002) Activated mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in the pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis complex renal tumors. Cancer Res 62: 5645–5650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilberg MS, Shan J, Su N (2009) ATF4‐dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 20: 436–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D‐H, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument‐Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM (2002) mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient‐sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell 110: 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Goraksha‐Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP, Guan K‐L (2008) Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat Cell Biol 10: 935–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A, Cunningham KW (2015) A LAPF/phafin1‐like protein regulates TORC1 and lysosomal membrane permeabilization in response to endoplasmic reticulum membrane stress. Mol Biol Cell 26: 4631–4645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, An S, Ro S‐H, Teixeira F, Park GJ, Kim C, Cho C‐S, Kim J‐S, Jakob U, Lee JH, Cho U‐S (2015a) Janus‐faced Sestrin2 controls ROS and mTOR signalling through two separate functional domains. Nat Commun 6: 10025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Ro S‐H, Kim M, Park H‐W, Semple IA, Park H, Cho U‐S, Wang W, Guan K‐L, Karin M, Lee JH (2015b) Sestrin2 inhibits mTORC1 through modulation of GATOR complexes. Sci Rep 5: 9502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira S, Tabata K, Shirahama‐Noda K, Nozoe A, Yoshimori T, Noda T (2014) Reciprocal conversion of Gtr1 and Gtr2 nucleotide‐binding states by Npr2‐Npr3 inactivates TORC1 and induces autophagy. Autophagy 10: 1565–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira S, Kumano Y, Ukai H, Takeda E, Matsuura A, Noda T (2015) Dynamic relocation of the TORC1‐Gtr1/2‐Ego1/2/3 complex is regulated by Gtr1 and Gtr2. Mol Biol Cell 27: 382–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasson H, Fink GR, Ljungdahl PO (1999) Ssy1p and Ptr3p are plasma membrane components of a yeast system that senses extracellular amino acids. Mol Cell Biol 19: 5405–5416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Shimabukuro‐Demoto S, Yoshida‐Sugitani R, Furuyama‐Tanaka K, Karyu H, Sugiura Y, Shimizu Y, Hosaka T, Goto M, Kato N, Okamura T, Suematsu M, Yokoyama S, Toyama‐Sorimachi N (2014) The histidine transporter SLC15A4 coordinates mTOR‐dependent inflammatory responses and pathogenic antibody production. Immunity 41: 375–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan K, Spear ED, Kaiser CA, Fass D (2010) Structural conservation of components in the amino acid sensing branch of the TOR pathway in yeast and mammals. J Mol Biol 402: 388–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota H, Obata T, Ota K, Sasaki T, Ito T (2003) Rapamycin‐induced translational derepression of GCN4 mRNA involves a novel mechanism for activation of the eIF2 alpha kinase GCN2. J Biol Chem 278: 20457–20460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz J, Henriquez R, Schneider U, Deuter‐Reinhard M, Movva NR, Hall MN (1993) Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression. Cell 73: 585–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Zhang H, Bandura JL, Heiberger KM, Glogauer M, el‐Hashemite N, Onda H (2002) A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex‐dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up‐regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum Mol Genet 11: 525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM (2013) mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149: 274–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Budanov AV, Karin M (2013) Sestrins orchestrate cellular metabolism to attenuate aging. Cell Metab 18: 792–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Cho U‐S, Karin M (2016) Sestrin regulation of TORC1: is Sestrin a leucine sensor? Sci Signal 9: re5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine TP, Daniels RD, Wong LH, Gatta AT, Gerondopoulos A, Barr FA (2013) Discovery of new longin and roadblock domains that form platforms for small GTPases in ragulator and TRAPP‐II. Small GTPases 4: 62–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liko D, Hall MN (2015) mTOR in health and in sickness. J Mol Med (Berl) 93: 1061–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungdahl PO (2009) Amino‐acid‐induced signalling via the SPS‐sensing pathway in yeast. Biochem Soc Trans 37: 242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungdahl PO, Daignan‐Fornier B (2012) Regulation of amino acid, nucleotide, and phosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics 190: 885–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN (2002) Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell 10: 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewith R, Hall MN (2011) Target of rapamycin (TOR) in nutrient signaling and growth control. Genetics 189: 1177–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz‐Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J (2005) Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase. Curr Biol 15: 702–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC (2002) Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex‐2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3‐kinase/akt pathway. Mol Cell 10: 151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez P, Ljungdahl PO (2005) Divergence of Stp1 and Stp2 transcription factors in Candida albicans places virulence factors required for proper nutrient acquisition under amino acid control. Mol Cell Biol 25: 9435–9446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami H, Montmayeur JP, Buck LB (2000) A family of candidate taste receptors in human and mouse. Nature 404: 601–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon S, Dibble CC, Talbott G, Hoxhaj G, Valvezan AJ, Takahashi H, Cantley LC, Manning BD (2014) Spatial control of the TSC complex integrates insulin and nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome. Cell 156: 771–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkereit R, Persaud A, Vanoaica L, Guetg A, Verrey F, Rotin D (2015) LAPTM4b recruits the LAT1‐4F2hc Leu transporter to lysosomes and promotes mTORC1 activation. Nat Commun 6: 7250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima N, Noguchi E, Nishimoto T (1999) Saccharomyces cerevisiae putative G protein, Gtr1p, which forms complexes with itself and a novel protein designated as Gtr2p, negatively regulates the Ran/Gsp1p G protein cycle through Gtr2p. Genetics 152: 853–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan J, Staschke KA, Wek RC (2004) Dimerization is required for activation of eIF2 kinase Gcn2 in response to diverse environmental stress conditions. J Biol Chem 279: 22820–22832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Feng L, Zhao G, Ryba NJP, Zuker CS (2002) An amino‐acid taste receptor. Nature 416: 199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklin P, Bergman P, Zhang B, Triantafellow E, Wang H, Nyfeler B, Yang H, Hild M, Kung C, Wilson C, Myer VE, MacKeigan JP, Porter JA, Wang YK, Cantley LC, Finan PM, Murphy LO (2009) Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell 136: 521–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ögmundsdóttir MH, Heublein S, Kazi S, Reynolds B, Visvalingam SM, Shaw MK, Goberdhan DCI (2012) Proton‐assisted amino acid transporter PAT1 complexes with Rag GTPases and activates TORC1 on late endosomal and lysosomal membranes. PLoS ONE 7: e36616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omnus DJ, Pfirrmann T, Andréasson C, Ljungdahl PO (2011) A phosphodegron controls nutrient‐induced proteasomal activation of the signaling protease Ssy5. Mol Biol Cell 22: 2754–2765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onda H, Crino PB, Zhang H, Murphey RD, Rastelli L, Gould Rothberg BE, Kwiatkowski DJ (2002) Tsc2 null murine neuroepithelial cells are a model for human tuber giant cells, and show activation of an mTOR pathway. Mol Cell Neurosci 21: 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchaud N, Péli‐Gulli M‐P, De Virgilio C (2013a) Amino acid deprivation inhibits TORC1 through a GTPase‐activating protein complex for the Rag family GTPase Gtr1. Sci Signal 6: ra42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchaud N, Péli‐Gulli M‐P, De Virgilio C (2013b) SEACing the GAP that nEGOCiates TORC1 activation: evolutionary conservation of Rag GTPase regulation. Cell Cycle 12: 2948–2952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmigiani A, Nourbakhsh A, Ding B, Wang W, Kim YC, Akopiants K, Guan K‐L, Karin M, Budanov AV (2014) Sestrins inhibit mTORC1 kinase activation through the GATOR complex. Cell Rep 9: 1281–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LR, Komander D, Alessi DR (2010) The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 9–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péli‐Gulli M‐P, Sardu A, Panchaud N, Raucci S, De Virgilio C (2015) Amino acids stimulate TORC1 through Lst4‐Lst7, a GTPase‐activating protein complex for the rag family GTPase Gtr2. Cell Rep 13: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Yin N, Li MO (2014) Sestrins function as guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors for Rag GTPases to control mTORC1 signaling. Cell 159: 122–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit CS, Roczniak‐Ferguson A, Ferguson SM (2013) Recruitment of folliculin to lysosomes supports the amino acid‐dependent activation of Rag GTPases. J Cell Biol 202: 1107–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfirrmann T, Heessen S, Omnus DJ, Andréasson C, Ljungdahl PO (2010) The prodomain of Ssy5 protease controls receptor‐activated proteolysis of transcription factor Stp1. Mol Cell Biol 30: 3299–3309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plescher M, Teleman AA, Demetriades C (2015) TSC2 mediates hyperosmotic stress‐induced inactivation of mTORC1. Sci Rep 5: 13828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen P, Lo Leggio L, Kielland‐Brandt MC (2006) Mapping of an internal protease cleavage site in the Ssy5p component of the amino acid sensor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and functional characterization of the resulting pro‐ and protease domains by gain‐of‐function genetics. Eukaryot Cell 5: 601–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis K, Zhang T, Panchaud N, Wang R, De Virgilio C, Ding J (2015) Crystal structure of the Ego1‐Ego2‐Ego3 complex and its role in promoting Rag GTPase‐dependent TORC1 signaling. Cell Res 25: 1043–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis K, De Virgilio C (2016) Conserved regulators of Rag GTPases orchestrate amino acid‐dependent TORC1 signaling. Cell Discov 2: 15049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebsamen M, Pochini L, Stasyk T, de Araújo MEG, Galluccio M, Kandasamy RK, Snijder B, Fauster A, Rudashevskaya EL, Bruckner M, Scorzoni S, Filipek PA, Huber KVM, Bigenzahn JW, Heinz LX, Kraft C, Bennett KL, Indiveri C, Huber LA, Superti‐Furga G (2015) SLC38A9 is a component of the lysosomal amino acid sensing machinery that controls mTORC1. Nature 519: 477–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russnak R, Konczal D, McIntire SL (2001) A family of yeast proteins mediating bidirectional vacuolar amino acid transport. J Biol Chem 276: 23849–23857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini DM, Erdjument‐Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH (1994) RAFT1: a mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin‐dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell 78: 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT (1995) Isolation of a protein target of the FKBP12‐rapamycin complex in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 270: 815–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar‐Peled L, Sabatini DM (2008) The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science 320: 1496–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Bar‐Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM (2010) Ragulator‐Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell 141: 290–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, Chantranupong L, Knockenhauer KE, Schwartz TU, Sabatini DM (2016a) Mechanism of arginine sensing by CASTOR1 upstream of mTORC1. Nature 536: 229–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, Knockenhauer KE, Schwartz TU, Sabatini DM (2016b) The apo‐structure of the leucine sensor Sestrin2 is still elusive. Sci Signal 9: ra92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, Knockenhauer KE, Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Pacold ME, Wang T, Schwartz TU, Sabatini DM (2016c) Structural basis for leucine sensing by the Sestrin2‐mTORC1 pathway. Science 351: 53–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürmann A, Brauers A, Massmann S, Becker W, Joost HG (1995) Cloning of a novel family of mammalian GTP‐binding proteins (RagA, RagBs, RagB1) with remote similarity to the Ras‐related GTPases. J Biol Chem 270: 28982–28988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi T, Hirose E, Nakashima N, Ii M, Nishimoto T (2001) Novel G proteins, Rag C and Rag D, interact with GTP‐binding proteins, Rag A and Rag B. J Biol Chem 276: 7246–7257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimobayashi M, Hall MN (2014) Making new contacts: the mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimobayashi M, Hall MN (2015) Multiple amino acid sensing inputs to mTORC1. Cell Res 26: 7–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin C‐S, Kim SY, Huh W‐K (2009) TORC1 controls degradation of the transcription factor Stp1, a key effector of the SPS amino‐acid‐sensing pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Cell Sci 122: 2089–2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu F, Bain PJ, LeBlanc‐Chaffin R, Chen H, Kilberg MS (2002) ATF4 is a mediator of the nutrient‐sensing response pathway that activates the human asparagine synthetase gene. J Biol Chem 277: 24120–24127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staschke KA, Dey S, Zaborske JM, Palam LR, McClintick JN, Pan T, Edenberg HJ, Wek RC (2010) Integration of general amino acid control and target of rapamycin (TOR) regulatory pathways in nitrogen assimilation in yeast. J Biol Chem 285: 16893–16911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracka D, Jozefczuk S, Rudroff F, Sauer U, Hall MN (2014) Nitrogen source activates TOR complex 1 via glutamine and independently of Gtr/Rag. J Biol Chem 289: 25010–25020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter BM, Wu X, Laxman S, Tu BP (2013) Methionine inhibits autophagy and promotes growth by inducing the SAM‐responsive methylation of PP2A. Cell 154: 403–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PM (2014) Role of amino acid transporters in amino acid sensing. Am J Clin Nutr 99: 223S–230S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Cantley LC, Blenis J (2002) Tuberous sclerosis complex‐1 and ‐2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)‐mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 13571–13576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Zhang Y‐J, Wei Y‐H, Cho J‐H, Morris LE, Wang H‐Y, Zheng XFS (2014) Rab1A is an mTORC1 activator and a colorectal oncogene. Cancer Cell 26: 754–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsun Z‐Y, Bar‐Peled L, Chantranupong L, Zoncu R, Wang T, Kim C, Spooner E, Sabatini DM (2013) The folliculin tumor suppressor is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Mol Cell 52: 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano J, Tabancay AP, Yang W, Tamanoi F (2000) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rheb G‐protein is involved in regulating canavanine resistance and arginine uptake. J Biol Chem 275: 11198–11206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Geldermalsen M, Wang Q, Nagarajah R, Marshall AD, Thoeng A, Gao D, Ritchie W, Feng Y, Bailey CG, Deng N, Harvey K, Beith JM, Selinger CI, O'Toole SA, Rasko JEJ, Holst J (2016) ASCT2/SLC1A5 controls glutamine uptake and tumour growth in triple‐negative basal‐like breast cancer. Oncogene 35: 3201–3208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vattem KM, Wek RC (2004) Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 11269–11274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Tsun Z‐YZ‐Y, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant GA, Plovanich ME, Yuan ED, Jones TD, Chantranupong L, Comb W, Wang T, Bar‐Peled L, Zoncu R, Straub C, Kim C, Park J, Sabatini BL, Sabatini DM (2015) Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 347: 188–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauson EM, Zaganjor E, Lee A‐Y, Guerra ML, Ghosh AB, Bookout AL, Chambers CP, Jivan A, McGlynn K, Hutchison MR, Deberardinis RJ, Cobb MH (2012) The G protein‐coupled taste receptor T1R1/T1R3 regulates mTORC1 and autophagy. Mol Cell 47: 851–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek RC, Jackson BM, Hinnebusch AG (1989) Juxtaposition of domains homologous to protein kinases and histidyl‐tRNA synthetases in GCN2 protein suggests a mechanism for coupling GCN4 expression to amino acid availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 4579–4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek SA, Zhu S, Wek RC (1995) The histidyl‐tRNA synthetase‐related sequence in the eIF‐2 alpha protein kinase GCN2 interacts with tRNA and is required for activation in response to starvation for different amino acids. Mol Cell Biol 15: 4497–4506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Saxton RA, Shen K, Scaria SM, Cantor JR, Sabatini DM (2016) Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science 351: 43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN (2006) TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124: 471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Wang R, Zhang T, Ding J (2016) Structural insight into the arginine‐binding specificity of CASTOR1 in amino acid‐dependent mTORC1 signaling. Cell Discov 2: 16035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F, Huang Z, Li H, Yu J, Wang C, Chen S, Meng Q, Cheng Y, Gao X, Li J, Liu Y, Guo F (2011) Leucine deprivation increases hepatic insulin sensitivity via GCN2/mTOR/S6K1 and AMPK pathways. Diabetes 60: 746–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Palm W, Peng M, King B, Lindsten T, Li MO, Koumenis C, Thompson CB (2015) GCN2 sustains mTORC1 suppression upon amino acid deprivation by inducing Sestrin2. Genes Dev 29: 2331–2336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon MS, Du G, Backer JM, Frohman MA, Chen J (2011) Class III PI‐3‐kinase activates phospholipase D in an amino acid‐sensing mTORC1 pathway. J Cell Biol 195: 435–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon MS, Son K, Arauz E, Han JM, Kim S, Chen J (2016) Leucyl‐tRNA synthetase activates Vps34 in amino acid‐sensing mTORC1 signaling. Cell Rep 16: 1510–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Fagotto F, Zhang T, Hsu W, Vasicek TJ, Perry WL, Lee JJ, Tilghman SM, Gumbiner BM, Costantini F (1997) The mouse Fused locus encodes Axin, an inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway that regulates embryonic axis formation. Cell 90: 181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Péli‐Gulli M‐P, Yang H, De Virgilio C, Ding J (2012) Ego3 functions as a homodimer to mediate the interaction between Gtr1‐Gtr2 and Ego1 in the ego complex to activate TORC1. Structure 20: 2151–2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y‐L, Guo H, Zhang C‐S, Lin S‐Y, Yin Z, Peng Y, Luo H, Shi Y, Lian G, Zhang C, Li M, Ye Z, Ye J, Han J, Li P, Wu J‐W, Lin S‐C (2013) AMP as a low‐energy charge signal autonomously initiates assembly of AXIN‐AMPK‐LKB1 complex for AMPK activation. Cell Metab 18: 546–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C‐S, Jiang B, Li M, Zhu M, Peng Y, Zhang Y‐L, Wu Y‐Q, Li TY, Liang Y, Lu Z, Lian G, Liu Q, Guo H, Yin Z, Ye Z, Han J, Wu J‐W, Yin H, Lin S‐Y, Lin S‐C (2014) The lysosomal v‐ATPase‐Ragulator complex is a common activator for AMPK and mTORC1, acting as a switch between catabolism and anabolism. Cell Metab 20: 526–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R, Bar‐Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM (2011) mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside‐out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)‐ATPase. Science 334: 678–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]