Abstract

Rates of chlamydia (CT) and gonorrhea (GC) have risen for the first time in the United States since 2006. Certain population groups are disproportionately affected by these sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as well as HIV. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and professional societies have published screening guidelines for these STIs for women under the age of 25. We aimed to quantify physician adherence to GC/CT and HIV screening guidelines and to determine demographic factors associated with GC/CT and HIV screening recommendations among women 14–25 years old in Honolulu, Hawai‘i. We conducted a retrospective chart review of all visits to an OB/GYN teaching clinic in 2014 to determine rates of STI screening recommendations and evaluate differences in screening recommendations by demographic factors such as patient age, race, insurance type, visit type, and visit number during the study period. Electronic medical records of 726 visits by 446 patients were reviewed. Among visits by patients with indications for screening, 71.0% and 21.6% received screening recommendations for GC/CT and HIV, respectively. Age group, race, and visit type were significantly associated with receiving screening recommendations. A lack of appropriate documentation regarding the assessment of risk factors for GC/CT and HIV screening was observed. Emphasis should be placed on more thorough ascertainment and documentation of patients' risk factors for STI acquisition to determine screening needs at each clinical visit based on professional guidelines, as substantial public health benefits may be gained through the identification and prompt treatment of GC/CT and HIV infections.

Keywords: chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV, sexually transmitted infection, screening, Hawai‘i, adolescent, resident physician

Introduction

In 2014, rates of chlamydia (CT) and gonorrhea (GC) infections rose for the first time since 2006 in the United States (U.S.).1 Surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) demonstrated a CT rate increase of 2.8% in 2014 (456.1 cases per 100,000, compared to 443.5 cases per 100,000 in 2013). The GC rate increased from the previous year by 5.1% (110.7 cases per 100,000 compared to 105.3 cases per 100,000 in 2013).1 These sexually transmitted infections (STIs) disproportionately affect young people and people of color.2 In 2014, 66% of all CT cases were found in young people aged 15–24, despite this group comprising less than 14% of the total U.S. population.2,3 Furthermore, national incidence rates of chlamydia infections among Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) populations were 3.5 times greater than among Whites and 5.7 times greater than among Asians in 2013. Similarly, gonorrhea incidence among NHOPI were 2.7 times greater than Whites in the U.S.4 In the same year, Hawai‘i, the state with the largest percentage of these racial groups, had higher reported rates of CT infection than the national average, ranking 15th among the 50 states.5,6 Although national Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) incidence has declined since 2005, and the incidence in Hawai‘i is relatively low (38th among the 50 states), the life-threatening consequences of this infection underscore the importance of routine screening.6–9

Chlamydia, gonorrhea and HIV infections are frequently asymptomatic, and untreated infections may have severe long-term health consequences. Among women, chlamydial and gonorrheal infections increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, and undiagnosed and untreated HIV can progress to Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).7–11 Unrecognized transmission of these infections to sexual partners is a substantial public health concern. It is for these reasons that the CDC and the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend annual chlamydia and gonorrhea screening for all sexually active women under 25 years of age, with additional screening when new risk factors are identified.12,13 These risk factors include new or multiple partners, having a partner with a sexually transmitted infection, having a partner with concurrent partners, or having symptoms of infection. All persons aged 13–64 are recommended to receive HIV screening at least once in their lives, and more frequently for risk factors such as unprotected sex or use of injection drugs.14 Despite clear guidelines for routine GC/CT and HIV screening, many physicians do not routinely recommend such testing, and less than half of all sexually active women under 25 years of age reported having been screened for an STI in 2009.15 Each clinical visit is an important opportunity to assess new or continuing risk factors for GC/CT and HIV and to make appropriate recommendations for testing, as patients may present with additional indications at any time and may not present for scheduled preventive health visits. Thorough documentation of this information, as well as testing history, are critical to the provision of high quality reproductive health care in this age group with documented disparities in the incidence of sexually transmitted infections.

The purpose of this study is to (1) quantify physician adherence to GC/CT and HIV screening guidelines (2) quantify the proportion of patient visits in which recommended screening was received, and (3) identify demographic factors associated with GC/CT and HIV screening recommendations among visits by women 14–25 years old to an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) resident clinic in Honolulu, Hawai‘i.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of all patient visits by non-pregnant women ages 14–25 years at a single outpatient OB/GYN resident clinic in 2014. Researchers reviewed resident and attending physician notes, problem list tabs, laboratory tests ordered and conducted, and scanned media files of testing received outside of our health system in each respective electronic health record (EHR). Women with a minimum age of 14 were included in the review as this is the age at which patients are able to provide consent for reproductive health services in Hawai‘i.16 Pregnant women were excluded from the study as they are a special population with unique STI screening recommendations.11 Some patients were seen more than once during the study period and each visit was viewed as a unique encounter and recorded independently, as new or additional STI risk factors may have been reported during subsequent visits during the study period. Demographic variables contained within the EHR such as age, race, insurance type, visit type, and number of clinic visits within the study period were collected. Age was recorded as a dichotomous variable, 14–19 or 20–25 years. This was to facilitate comparison of outcomes between patients considered adolescent (14–19) and young adult (20–25). The study was approved by the Hawai‘i Pacific Health Research Institute and the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB Protocol # 20150630).

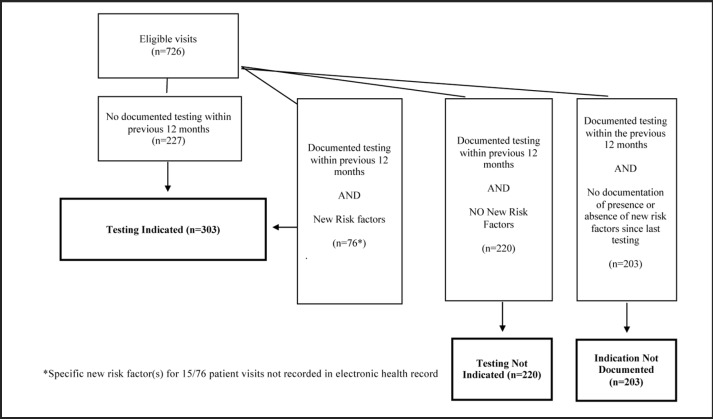

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The primary outcome variable was a documented recommendation for GC/CT screening by a resident or attending physician among patients indicated for screening per CDC/USPSTF guidelines. Indications for GC/CT screening were defined as: lack of documented history of GC/CT testing in the prior 12 months (if sexually active), or the presence of new risk factors, including new or multiple partners, symptoms potentially indicative of an STI, a positive test for another STI since last testing, a partner with positive test for any STI since last testing, or concern that a sexual partner had new concurrent partners since last testing. Patients with a documented GC/CT test within the past 12 months, but without explicit documentation of the presence or lack of risk factors at the current visit, were categorized as “indication not documented”. Patients without a documented GC/CT test within the past 12 months were categorized as indicated for GC/CT screening at the current visit (Figure 1). An additional study outcome was a documented recommendation for HIV screening among patients with indications for screening. Indications for HIV screening included: never having been screened for HIV (if sexually active) or the presence of new risk factors such as diagnosis of an STI since last testing, unprotected sex since last testing, having a partner with an STI since last testing, new or multiple partners, injection drug use by self or partner, or having a partner with new or concurrent partners since last testing. Patients with lack of documentation of ever receiving an HIV test were categorized as indicated for HIV screening at the current visit (Figure 2). The secondary study outcome was documentation of GC/CT and/or HIV testing having been performed when recommended by a physician. This was determined by reviewing laboratory tests, and scanned media results from testing conducted in other facilities, within the medical record.

Figure 1.

Determination of Testing Indications for GC/CT

Figure 2.

Determination of Testing Indications for HIV

To identify factors potentially associated with GC/CT and HIV screening recommendations, Chi-square tests of independence or Fisher's exact tests (when n<5), and bivariable generalized linear models with logit link functions were employed among all demographic variables collected. Potentially significant variables (P<.1) were then examined using a multivariable generalized linear model, with a logit link function, to identify associations after controlling for other factors.

Results

A total of 1,039 clinic visits by non-pregnant women aged 14–25 in 2014 were initially reviewed. Of those visits, 313 were excluded due to self-reported virginal status documented in the medical record, a new diagnosis of pregnancy, or receipt of only ancillary services (such as a vaccination or pregnancy test not including interaction with a physician), resulting in 726 remaining visits among 446 patients with potential indications for STI screening. Indications for GC/CT and HIV screening were present in 41.7% (303 visits among 192 patients) and 42.1% (306 visits among 188 patients) of all eligible visits, respectively. The majority of unique patients with indications for GC/CT and/or HIV screening were Asian or Native Hawaiian and seen once during the study period. Medicaid was the most common payer in this population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics: Demographics of unique patients with visits that included indications for GC/CT screening (n=192) and HIV screening (n=188)

| Patients with GC/CT testing indication (n=192) | Patients with HIV testing indication (n=188) | |

| Age Group | ||

| 14–19 | 80 (42%) | 95 (51%) |

| 20–25 | 112 (58%) | 93 (49%) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 61 (32%) | 62 (33%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 63 (33%) | 46 (24%) |

| Other | 16 (8%) | 16 (9%) |

| Pacific Islander | 21 (11%) | 22 (12%) |

| White | 31 (16%) | 42 (22%) |

| Insurance* | ||

| Clinic subsidized visit | 13 (7%) | 16 (8%) |

| Federal | 4 (2%) | 5 (3%) |

| None | 29 (15%) | 37 (20%) |

| Private | 40 (21%) | 42 (22%) |

| Public | 106 (55%) | 88 (47%) |

| Visit Type** | ||

| Annual Exam | 80 (42%) | 56 (30%) |

| Gynecological Care | 105 (55%) | 131 (69%) |

| Postpartum Exam | 7 (3%) | 1 (1%) |

| Visit Number | ||

| Visited once | 140 (73%) | 129 (69%) |

| Visited twice | 37 (19%) | 43 (23%) |

| Visited 3 or more times | 15 (8%) | 16 (8%) |

Federal = coverage received by members of the military or their dependents , as well as some federal civilian employees

Public = coverage provided by state government programs, such as Medicaid/Quest

Initial visit type among patients who were seen more than once during the study period

GC/CT Screening Recommendations

Three hundred and three visits, representing 192 unique patients, had an indication for GC/CT screening. Recommendations for screening were documented in 71.0% (215) of all indicated patient visits. When recommended during the visit, GC/CT screening was conducted at a rate of 85.6% (184), while screening was not completed at a rate of 14.4% (31). Among visits in which recommended testing was not completed, 45% (14) of patients declined and for 55% (17) of patients, the medical record contained no documented reason for why testing wasn't performed. Among those tested, 6% (11) of tests returned positive for CT. No positive GC tests were reported.

Bivariate analyses evaluating the association between testing recommendations among indicated patients and demographic variables revealed a significant association with age group (P<.0001), race, (P<.0001), insurance type (P<.0001), visit type (P=.0039), and visit number (P<.0001). The multivariable model demonstrated a higher likelihood of receiving a recommendation for indicated GC/CT screening among visits scheduled as annual gynecologic preventive care exams, after adjusting for the effects of age group, race, insurance type, and visit number (Adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR]:7.61 95% CI: 3.65–16.66) (Table 2). All other covariates were found to be statistically non-significant.

Table 2.

GC/CT Screening Recommendations Bivariable and Multivariable Analysis: Unadjusted and adjusted* odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of receiving recommendations for GC/CT among indicated visits (n=303)

| OR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Age Group | ||||

| 14–19 | 0.91 | 0.55–1.51 | 1.30 | 0.64–2.39 |

| 20–25 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 0.38 | 0.14–0.93 | 0.53 | 0.71–1.48 |

| Native Hawaiian | 0.41 | 0.15–1.01 | 0.66 | 0.19–1.85 |

| Other | 0.65 | 0.18–2.32 | 1.12 | 0.24–4.62 |

| Pacific Islander | 0.31 | 0.11–0.92 | 0.59 | 0.27–2.1 |

| White | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Insurance | ||||

| Clinic subsidized visit | 1.78 | 0.57–5.61 | 1.91 | 0.53–6.89 |

| Federal | 2.85 | 0.34–24.25 | 1.70 | 0.18–17.12 |

| None | 1.64 | 0.73–3.66 | 1.37 | 0.51–3.69 |

| Private | 1.33 | 0.67–2.63 | 1.38 | 0.64–2.98 |

| Public | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Visit Type | ||||

| Annual Exam | 9.03 | 3.51–15.63 | 7.61 | 3.48–16.66 |

| Gynecological Care | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Postpartum Exam | 0.32 | 0.11.0.89 | 0.34 | 0.11–1.05 |

| Visit Number | ||||

| 1 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2 | 0.68 | 0.36–1.26 | 0.96 | 0.48–1.90 |

| 3+ | 1.02 | 0.41–2.54 | 1.58 | 0.59–4.22 |

Adjusted for age group, race, insurance, visit type, and visit number

HIV Screening Recommendations

Three hundred and six patient visits, representing 188 unique patients, had an indication for HIV screening. Among those patient visits, 21.6% (66) resulted in a recommendation for screening. When recommended, HIV testing was completed 42% (28) of the time. Among visits in which testing was not completed, 58% (22) of patients declined, 37% (14) were referred elsewhere for testing, and for 5% (2) of patients there were no documented reasons for why testing wasn't performed. All HIV tests resulted as negative.

Bivariable analyses evaluating the potential associations between screening recommendations among indicated patients and demographic variables revealed significant associations with age group (P<.0001), race (P<.0001), insurance type (P<.0001), visit type (P<.0001, and visit number (P<.0001). The multivariable model demonstrated a significantly greater likelihood of receiving a recommendation for HIV testing when indicated among patients who were Native Hawaiian or Other race, adolescent, or were presenting for an annual exam (Table 3).

Table 3.

HIV Screening Recommendations Bivariable and Multivariable Analysis: Unadjusted and adjusted* odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of receiving recommendations for HIV testing among indicated visits (n=306)

| OR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Age Group | ||||

| 14–19 | 5.92 | 2.67–13.09 | 5.66 | 2.29–14.02 |

| 20–25 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 3.61 | 1.16–11.20 | 2.95 | 0.87–10.07 |

| Native Hawaiian | 5.85 | 1.90–18.01 | 4.80 | 1.41–16.32 |

| Other | 4.50 | 1.15–17.67 | 4.44 | 1.00–19.77 |

| Pacific Islander | 0.46 | 0.05–4.29 | 0.47 | 0.04–4.98 |

| White | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Insurance | ||||

| Clinic subsidized visit | 1.75 | 0.70–4.40 | 1.47 | 0.50–4.32 |

| Federal | 0.49 | 0.06–4.08 | 0.59 | 0.05–6.65 |

| None | 0.29 | 0.08–0.99 | 0.56 | 0.14–2.19 |

| Private | 0.80 | 0.37–1.76 | 0.91 | 0.38–2.19 |

| Public | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Visit Type | ||||

| Annual Exam | 1.4 | 0.73–2.68 | 2.26 | 1.00–5.09 |

| Gynecological Care | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Visit Number | ||||

| 1 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2 | 0.45 | 0.19–1.05 | 0.42 | 0.17–1.06 |

| 3+ | 0.38 | 0.11–1.32 | 0.33 | 0.09–1.23 |

Adjusted for age group, race, insurance, visit type, and visit number

Note: Among 7 postpartum visits with indications for testing, no visits included a recommendation for HIV screening.

Discussion

While recommendations for GC/CT and HIV screening are clear for women under age 25, our study identified a significant gap in physician adherence to such guidelines in an OB/GYN teaching clinic. Specifically, GC/CT screening was not recommended in approximately 30% of visits in which it was indicated. Further, we identified a lack of adequate physician documentation regarding the presence of new risk factors for GC/CT and HIV infections in women who had documented testing in the past 12 months, or ever, respectively, which points toward the likelihood of an even higher rate of missed testing. However, when physicians recommended GC/CT screening, 85.5% of patients underwent testing during the visit. This highlights the importance of physician recommendations as an important link in ensuring adolescents and young adults receive appropriate STI screening, as well as patient willingness to be screened when prompted. In contrast, the majority of patient visits with indications for HIV screening did not include a recommendation for screening, and when prompted approximately half (58%) of patients declined screening at these visits. Further analysis should be conducted on motivators and barriers to HIV screening among this population.

Bivariable and multivariable modeling showed significant associations between the receipt of GC/CT screening recommendations among indicated patients and demographic factors. Although the effects of race were attenuated and no longer statistically significant after controlling for other factors, a decreased likelihood of receiving GC/CT screening recommendations among indicated Asian and Pacific Islander compared to White patients remained. These findings should be examined further in a larger sample through which more precise estimates may be ascertained. Having a visit scheduled as an annual gynecological preventative appointment was identified as the strongest predictor of receiving GC/CT and HIV screening recommendations in alignment with professional guidelines in this study. It is likely that physicians are attuned to addressing STI screening at these dedicated visits, however, interventions should be implemented to prompt screening during other types of scheduled visits. Visits by patients aged 14–19, Native Hawaiians or other race women, were more likely to receive appropriate HIV screening recommendations, which suggests a need to further evaluate factors influencing physician provision of testing recommendations.

Strengths of this study include that it is the first to analyze physician adherence to professional STI screening guidelines over a full calendar year in a population with nationally documented disparities in GC/CT incidence (Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders)4 in Hawai‘i. Despite having unique health experiences, NHOPI are commonly grouped into a single race category in national data. As Hawai‘i has the largest proportion of these racial groups in the nation, this clinic is an ideal setting to evaluate testing rates for these and other groups that are generally underrepresented nationally.5 Additionally, we were able to assess actual tests conducted. This has not been possible in prior studies using administrative data such as laboratory billing, or national surveys, which is unable to accurately differentiate between recommendations provided and testing conducted19–22 Furthermore, the study site represents the primary OB/GYN resident training site in the State of Hawai‘i. Future physician interventions aimed at increasing physician adherence to STI screening guidelines would have substantial impacts on reproductive health practices in the state.

This study also has several limitations. First, the small number of observations available for some study outcomes (particularly HIV screening recommendations) reduced precision and limited our statistical power to detect associations between demographic factors and provision of testing recommendations. Additionally, physicians may have made recommendations for STI testing but failed to document them in the EHR, causing such recommendations to be missed if the tests were not ordered. Second, all GC/CT and/or HIV testing conducted at non-affiliated institutions may not have been captured in our study, particularly when such testing wasn't endorsed by patients. However, we consider our comprehensive review of notes (including patient self-report of prior screening), problem list tabs, and scanned media from outside facilities within the EHR to have optimized collection of this data. Third, additional risk factors for HIV screening such as intravenous (IV) drug use have not been routinely assessed in this setting, which may have led to an under recognition of HIV testing indications. Fourth, the results of this study may be limited in generalizability. The data originated from a single hospital-based clinic. A larger sample that includes males, private offices, and state-run clinics, and the collection of data that contains patients' motivations for accepting or refusing testing, may provide additional insights regarding trends in screening gaps among specific demographic groups. Lastly, patients were restricted from choosing multiple race categories for inclusion in the electronic health record. Allowing the selection of multiple races may influence the effect of race and ethnicity on GC/CT screening recommendations, as an estimated 23% of Hawai‘i residents self-identify with two or more races.3

In summary, among patient visits with a documented indication(s) for screening, 29.0% were not recommended for GC/CT screening and 78.4% were not recommended for HIV screening in this resident training clinic. Annual gynecologic preventive health visits were positively associated with receiving GC/CT and HIV screening recommendations. Groups such as women aged 14–19, Native Hawaiians, or other races had greater likelihood of receiving recommendations for HIV screening when indicated. Moving forward, emphasis should be placed on interventions aimed at increasing physician documentation of STI risk factors, and promoting screening at all clinical opportunities to increase adherence to screening guidelines, as substantial public health benefits may be gained through the identification and prompt treatment of GC/CT and HIV infections.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by grant number #5U54MD007584-05 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIMHD or NIH.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CT

chlamydia

- EHR

electronic health record

- GC

gonorrhea

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- NHOPI

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify any conflicts of interest related to this publication.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2014. 2015. [January 21, 2016]. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/std-trends-508.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. STDs in Adolescents and Young Adults. 2015. [January 21, 2016]. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/adol.htm.

- 3.United States Census Bureau, author. American Fact Finder. [January 21, 2016]. http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_14_1YR_S0101&prodType=table.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. STDs in Racial and Ethnic Minorities. 2014. [January 21, 2016]. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats13/minorities.htm.

- 5.Hixson, Hepler BR, Kim MO. The Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander Population: 2010. 2012. [January 21, 2016]. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-12.pdf.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Hawaii — 2015 State Health Profile. 2015. [January 21, 2016]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/stateprofiles/pdf/hawaii_profile.pdf.

- 7.Davaro RE, Thirumalai A. Life-threatening consequences of HIV infection. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2007;22(2):73–81. doi: 10.1177/0885066606297964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD, Low N, Xu F, Ness RB. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;(201 Suppl 2):S134–S155. doi: 10.1086/652395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Aghaizu A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of screening for Chlamydia trachomatis to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: the POPI (prevention of pelvic infection) trial. BMJ (Clinical Research Education) 2010;340:c1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cates W, Jr, Wasserheit JN. Genital chlamydial infections: epidemiology and reproductive sequelae. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;164:1771–1781. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90559-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker CE, Sweet RL. Gonorrhea Infection in Women. Prevalence, Effects, Screening, and Management. International Journal of Women's Health. 2011;3:197–206. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(No. RR-3):1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Screening for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea: U.S. Preventative Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;161(12):I–30. doi: 10.7326/P14-9042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Routine human immunodeficiency virus screening. Committee Opinion No. 596. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;123:1137–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000446828.64137.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Quality Assurance, author. The State of Healthcare Quality. 2010. [January 21, 2016]. https://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/State%20of%20Health%20Care/2010/SOHC%202010%20-%20Full2.pdf.

- 16.Guttmacher Institute, author. An Overview of Minors' Consent Laws. 2016. [November 11, 2016]. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law.

- 17.Wiehe SE, Rosenman MB, Wang J, Katz BP, Fortenberry JD. Chlamydia Screening Among Young Women: Individual- and Provider- Level Differences in Testing. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e336–e344. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hipp LE, Kane Low L, Van Anders SM. Exploring Women's Postpartum Sexuality: Social, Psychological, Relational, and Birth-Related Contextual Factors. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9(9):2330–2341. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Malley KJ, Cook KF, Price MD, Raiford Wildes K, Hurdle JF, Ashton CM. Measuring Diagnoses: ICD Code Accuracy. Health Services Research. 2005;40:1620–1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Hiatt L. Screening for Chlamydia in Adolescents and Young Women. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescnt Medicine. 2000;154(11):1108–1113. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.11.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoover KW, Leichliter JS, Torrone EA, Loosier PS, Gift TL, Tao G. Chlamydia Screening Among Females Aged 15–21 Years - Multiple Data Sources, United States, 1999–2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63(02):80–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray MN, Wall T, Casebeer L, Weissman Norman, Spettell C, Abdolrasulnia M, Mian MAH, Collins B, Kiefe CI, Allison JJ. Chlamydia Screening of At-Risk Young Women in Managed Health Care: Characteristics of Top-Performing Primary Care Offices. http://journals.lww.com/stdjournal/Abstract/2005/06000/Chlamydia_Screening_of_At_Risk_Young_Women_in.10.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]