Abstract

Drosophila melanogaster has become a model system to study interactions between innate immunity and microbial pathogens, yet many aspects regarding its microbial community and interactions with pathogens remain unclear. In this study wild D. melanogaster were collected from tropical fruits in Puerto Rico to test how the microbiota is distributed and to compare the culturable diversity of fungi and bacteria. Additionally, we investigated whether flies are potential vectors of human and plant pathogens. Eighteen species of fungi and twelve species of bacteria were isolated from wild flies. The most abundant microorganisms identified were the yeast Candida inconspicua and the bacterium Klebsiella sp. The yeast Issatchenkia hanoiensis was significantly more common internally than externally in flies. Species richness was higher in fungi than in bacteria, but diversity was lower in fungi than in bacteria. The microbial composition of flies was similar internally and externally. We identified a variety of opportunistic human and plant pathogens in flies such as Alcaligenes faecalis, Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus, A. niger, Fusarium equiseti/oxysporum, Geotrichum candidum, Klebsiella oxytoca, Microbacterium oxydans, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Despite its utility as a model system, D. melanogaster can be a vector of microorganisms that represent a potential risk to plant and public health.

1. Introduction

The microbiota of wild Drosophila melanogaster is distinct from that of flies from laboratory stocks [1–4]. A wide range of bacteria from Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes phyla, among others, have been reported from Drosophila [2, 4]. In contrast, fungi are poorly characterized in Drosophila, with most studies focusing on taxonomy, ecology of yeast in the gut, and importance in the diet [5–7].

In the early 20th century, some Drosophila species were considered a potential vector of disease because its frequency near excrement and public toilets [8]. In a recent study, the Mediterranean fruit flies Ceratitis capitata and D. melanogaster were shown to transmit Escherichia coli to intact apple fruits, suggesting they are potential vectors of pathogens [9, 10]. This is a disturbing conclusion because D. melanogaster has a worldwide distribution and visits a wide variety of human foods [11]. Hence, fruit flies have been considered a common pest in the food industry [12]. In one instance, discovery of a population of fruit flies in an operating room at a New Jersey hospital resulted in the disruption of a dozen surgeries [13].

By the start of the 21st century, Drosophila had been established as a model system for immune studies after analysis of its genome revealed unsuspected sophistication and similarity to the mammalian innate immune system [14–16]. The use of Drosophila for studies of virulence and pathogen interactions requires a deeper knowledge of its microbial symbionts and their internal and external distributions.

In this study, we isolated microorganisms from wild D. melanogaster to answer the following questions: (1) how is the microbiota of Drosophila distributed spatially? We hypothesized that some microorganisms are found in both external and internal tissues of flies [17]; however, other bacteria and fungi will be limited to either internal or external surfaces. (2) Are culturable fungi and bacteria equally diverse in flies? We hypothesize that bacteria will be more diverse than fungi in D. melanogaster because they form stable relationships with flies in nature and are important food sources for larvae [4]. (3) Are fruit flies potential vectors of opportunistic pathogens? Because fruit flies can transport microorganisms of human concern [9, 10, 18], we hypothesize that some fungi and bacteria isolated from wild flies will be potential vectors of plant and animal pathogens.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sampling, Culture Media, and Isolation of Microorganisms

Wild females of Drosophila melanogaster were collected in Puerto Rico from tropical fruits (mango, orange, starfruit, and jackfruit). Only culturable microorganisms were included in order to obtain data and isolates for a related project on probiotics [19]. Flies were attracted using glass jars with fruit and jars were covered with gauze after enough flies entered the jar. This was repeated four times at one-month intervals for a total of 160 flies.

Fungi were isolated on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and bacteria on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA); they are common and nonselective media that provide enough nutrients to encourage growth of a range of fungi and bacteria, respectively. Fungi and bacteria were isolated externally and internally from 40 flies per sample as follows: 5 flies each were placed on plates of PDA and TSA and allowed to walk on the surface for five minutes. Another 10 flies per sample were then anesthetized with CO2, placed in a microcentrifuge tube with sterile water and Tween 80 (0.01%) and mixed in a vortex for 1 minute to release microbial cells from body surfaces [20]. The wash solution was then streaked on the culture media described above. Another 10 flies were surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for 1 min, rinsed three times with sterile water, and placed on PDA and TSA, five per plate. The guts of another 10 flies surface-sterilized were extracted using a sterile forceps and needle. Guts were rinsed in sterile water and streaked with a sterile loop on PDA and TSA (5 guts per plate). Plates were incubated at 28°C for seven days to allow microbial growth.

Microorganisms were isolated every day and plated in a 2 mL glass vial with PDA or TSA. Microorganisms were grouped by morphospecies based on morphological characteristics, for example, colony size, color, texture, and type of margin.

2.2. DNA Extraction

One fungal isolate from each morphospecies was cultured in Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB), filtered, and macerated in liquid nitrogen. DNA was extracted using a phenol-chloroform method [21]. The same procedure was used for Drosophila. One bacterial isolate from each morphospecies was cultured in liquid Nutrient broth for 24–48 hours, cells were then lysed by heat-shock and suspended in 1 mL of sterile distilled water, and DNA was diluted to 4–30 ng/μL for PCR.

2.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction and Sequencing

For fungi, the nuclear ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) was amplified using primers ITS 1F and ITS 4 [21, 22]. For bacteria, part of the 16S ribosomal gene was amplified using primers fD1 and rP2 [23]. For Drosophila, the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I was amplified with primers LCO1490 and HCO2198 [24]. Amplicons were 600–1300 nucleotides for bacteria, 200–500 nucleotides for fungi, and ~600 nucleotides for Drosophila. PCR products were cleaned using Exo-Sap (Fermentas) and sequenced in the Sequencing and Genotyping Facility (SGF) at UPR-RP. Sequences from flies, bacteria, and fungi (GenBank accession numbers KU238836–KU238862) were corrected with Sequencher software and identified by BLASTn searches in GenBank. Names assigned were based on >98% identity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identification and distribution of fungi and bacteria on and in fruit flies. GenBank accession numbers are for ITS sequences of fungi and 16S rDNA sequences for bacteria. The last six columns show numbers of each microorganism isolated with the following protocols: flies that walked across petri plates; flies washed in 0.01% Tween 80; surface-sterilized flies; and guts removed from flies.

| Strain | Species | GenBank accession ID | Highest hit | GenBank accession ID | % identity | External isolation | Internal isolation | Total | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walked | Washed | Insect | Gut | ||||||||

| Fungus | |||||||||||

| H137 | Candida inconspicua | KU238836 | Candida inconspicua | KT207004 | 100 | 27 | 20 | 23 | 14 | 84 | 0.275 |

| H35 | Penicillium crustosum/commune | KU238837 | Penicillium commune | KR012904 | 100 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 28 | 0.705 |

| H127 | Issatchenkia hanoiensis | KU238838 | Issatchenkia hanoiensis | FJ153178 | 99 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 0.013∗ |

| H66 | Aspergillus versicolor/sydowii/nidulans | KU238839 | Aspergillus sydowii | KT989398 | 100 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| H11 | Aspergillus fumigatus | KU238840 | Aspergillus fumigatus | AB298709 | 100 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0.655 |

| H37 | Fusarium sp. | KU238841 | Fusarium equiseti | HQ332532 | 100 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0.655 |

| H44 | Galactomyces candidum/geotrichium | KU238842 | Galactomyces candidum | KJ579946 | 99 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1.000 |

| H102 | Pichia membranifaciens | KU238843 | Pichia membranifaciens | FJ231462 | 99 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0.317 |

| H7 | Rhizopus sp. | — | — | — | — | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.083 |

| H24 | Fusarium equiseti/oxysporum | KU238844 | Fusarium equiseti | KJ174399 | 100 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0.564 |

| H77 | Penicillium citrinum/griseofulvum | KU238845 | Penicillium citrinum | KU681430 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0.564 |

| H31 | Aspergillus niger | KU238846 | Aspergillus niger | KP748369 | 99 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0.564 |

| H46 | Geotrichum candidum | KU238847 | Geotrichum candidum | KF713518 | 100 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.157 |

| H69 | Aspergillus flavus/oryzae | KU238848 | Aspergillus flavus | KU360621 | 100 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.317 |

| H70 | Aspergillus niger/tubingensis | KU238849 | Aspergillus niger | EU645723 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.317 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Bacteria | |||||||||||

| B82 | Klebsiella sp. | KU238850 | Klebsiella sp. | FN178363 | 99 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 13 | 32 | 0.077 |

| B5 | Bacillus sp. | KU238851 | Bacillus pumilus | KU517819 | 99 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 22 | 0.670 |

| B30 | Klebsiella oxytoca | KU238852 | Klebsiella michiganensis | KP717391 | 99 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 20 | 0.371 |

| B44 | Klebsiella pneumoniae/variicola | KU238853 | Klebsiella variicola | KT895843 | 99 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 14 | 0.109 |

| B22 | Erwinia sp. | KU238854 | Uncultured Erwinia sp. | HE575588 | 99 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 0.366 |

| B105 | Bacillus pumilus/safensis | KU238855 | Bacillus pumilus | KU239978 | 99 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 0.096 |

| B39 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | KU238856 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | LT222226 | 99 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 0.739 |

| B84 | Micrococcus luteus/yunnanensis | KU238857 | Micrococcus luteus | KT901825 | 100 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 1.000 |

| B43 | Alcaligenes faecalis | KU238858 | Alcaligenes faecalis | KU179370 | 99 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1.000 |

| B8 | Microbacterium oxydans | KU238859 | Microbacterium oxydans | KT580637 | 99 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.317 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Drosophila | |||||||||||

| D1 | Drosophila melanogaster | KU238860 | Drosophila melanogaster | KP161877 | 99 | ||||||

| D2 | Drosophila melanogaster | KU238861 | Drosophila melanogaster | KP161877 | 99 | ||||||

| D3 | Drosophila melanogaster | KU238862 | Drosophila melanogaster | KP161877 | 99 | ||||||

Asterisk represents significant differences by Chi square test.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

EstimateS (version 9.1.0 for Mac) was used to compare the richness (Chao 1), diversity (Shannon index), and composition (Bray-Curtis index) of communities in flies (http://viceroy.eeb.uconn.edu/estimates/). Species accumulation curves were obtained using the variable S (est). Chi square (χ2) tests were used to compare differences between external versus internal microbial communities.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution and Diversity of Microorganisms Isolated from Drosophila melanogaster

We isolated 314 microorganisms from wild Drosophila melanogaster, including 171 fungi and 143 bacteria, which were grouped into 18 and 12 morphospecies, respectively (Table 1). The most abundant fungus identified was the yeast Candida inconspicua which represented 49% of fungi isolated. The most common bacterial genus was Klebsiella (22%).

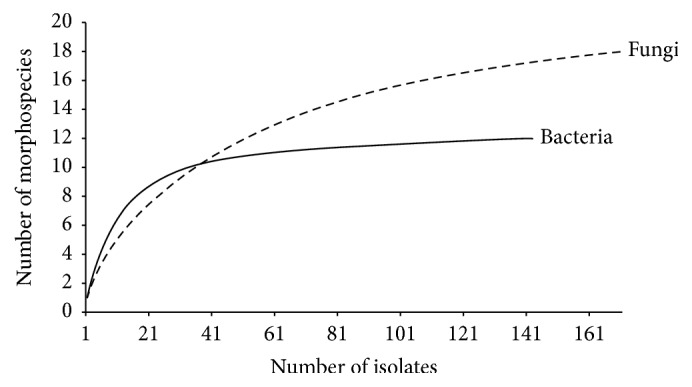

Species richness estimated as Chao 1 was 20 and 12, in fungal and bacterial communities, respectively. Species accumulation curves showed that for bacteria sampling was sufficient, assuming that our morphospecies did not contain cryptic species. For fungi the sampling was insufficient (Figure 1). The microbial diversity estimated with Shannon's index (H′) was 1.87 for fungi and 2.23 for bacteria.

Figure 1.

Species accumulation curves for fungal and bacterial morphospecies isolated from female Drosophila melanogaster in Puerto Rico. Species order was randomized 100 times. Fungal and bacterial species are represented with dashed and solid lines, respectively.

Only the yeast Issatchenkia hanoiensis (χ2 = 6.2, P < 0.013) was significantly more common in fly guts than external surfaces (Table 1). The remaining microorganisms did not differ significantly in frequency between external and internal origin (P > 0.05).

The species composition did not differ significantly between internal and external microbiotas, either for fungi (Bray-Curtis = 0.68) or for bacteria (Bray-Curtis = 0.71).

3.2. Potential Opportunistic Pathogens Isolated from Drosophila melanogaster

Bacteria and fungi isolated from Drosophila melanogaster included opportunistic pathogens of humans and animals, including Klebsiella oxytoca, Alcaligenes faecalis, Microbacterium oxydans, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Aspergillus fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. niger (Table 1). Also, A. flavus, A. niger, Fusarium equiseti/oxysporum, and Geotrichum candidum are considered opportunistic plant pathogens (Table 1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences between Bacteria and Fungi Isolated from Drosophila melanogaster

This study was limited to culturable microorganisms which were used for experiments on probiotics [19]. However, our protocol excluded the majority of bacteria and many fungi which are nonculturable or require specialized media or culture conditions [25].

The richness of fungal morphospecies was higher than that of bacteria (Figure 1). The accumulation curves for flies levelled off, suggesting that nearly all the culturable bacterial species present in flies were detected, but not for fungi. These results contradict a previous study where the fungal communities associated with different Drosophila species sampled around the world were less rich that those of bacteria [26]. However, that study only focused on yeasts isolated from guts of flies, which constitute the vast majority of known Drosophila-associated fungi.

In contrast, even though the fungal community is richer in species, the bacteria community is more diverse in D. melanogaster (H′, fungi = 1.87 versus bacteria = 2.23). This suggests that the population sizes of different bacterial species in the flies are more equitable. This is supported by two studies in which bacterial diversity exceeds fungal diversity in Drosophila populations [2, 26].

The yeast Issatchenkia hanoiensis was more abundant in internal parts of flies than externally (P < 0.013). Yeasts are common Drosophila symbionts, and some are food sources for Drosophila [26]. Yeast like Saccharomyces cerevisiae can survive passage through the digestive tract of flies because the constituents of spore walls are more resistant than vegetative cells [27]. It would be interesting to examine if I. hanoiensis provides any benefit to flies, for example, food source for larvae, roles in attraction, ovoposition, development, or protection against pathogens [5, 7, 28–31]. I. hanoiensis was first described in 2003 from insect frass; it has not previously been reported from Drosophila [32].

Apart from Issatchenkia, species composition internally versus externally in flies was similar for fungi (Bray-Curtis = 0.68) and for bacteria (Bray-Curtis = 0.71). This result contrasts with a previous microbiome study where the internal bacterial communities were a reduced subset of the external bacterial communities, suggesting that flies can control the microorganisms in the digestive tract and internal tissues [3].

4.2. Drosophila melanogaster as a Potential Vector of Pathogens

Drosophila melanogaster can carry opportunistic pathogens of humans [18]. We isolated the Gram-negative bacterium Klebsiella oxytoca which has been reported as a causal agent of hemorrhagic colitis, and Alcaligenes faecalis was previously associated with infections in newborns [33, 34]. Other microorganisms isolated in this study were also reported as emerging clinical pathogens, for example, Microbacterium oxydans and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia [35–38]. We also isolated three opportunistic pathogens capable of causing animal and human aspergillosis: Aspergillus fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. niger [39–42]. Their presence is not surprising because they are ubiquitous in nature with abundant airborne conidia [43].

Fruit flies as sources of contamination could represent a public health risk, especially to patients with compromised immune systems. For example, Mediterranean fruit flies (Ceratitis capitata) exposed to fecal material enriched with GFP-tagged Escherichia coli are capable of transmitting E. coli to intact apples in a cage model system [10]. The same was seen in D. melanogaster [9].

In addition, plant pathogens of agricultural concern were documented in the sampled flies, for example, A. niger, Fusarium equiseti/oxysporum, and Geotrichum candidum [44–47]. A. flavus causes substantial problems in agriculture as a source of aflatoxins and frequently enters plants through insect-induced wounds [40, 48].

Almost one hundred years ago, D. melanogaster, commonly found in exposed fruit in grocery stores and houses, was reported as “not an efficient disease carrier” [8]. This was based on the fact that D. melanogaster is rarely attracted to excrement. However, the studies mentioned support our hypothesis that flies might serve as vectors for opportunistic pathogens to humans and plants. More experiments are necessary to clarify the identity and virulence of the opportunistic pathogens found in this study.

5. Conclusions

The isolation of culturable microorganisms from wild D. melanogaster suggests that its microbiota is rich, diverse, and distributed throughout internal and external surfaces. Issatchenkia hanoiensis was identified as common component of the fly microbiota. Other microorganisms are related to opportunistic human pathogens, which may represent a public health risk, indicating D. melanogaster is a potential vector of disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of the doctoral thesis of Luis A. Ramírez-Camejo [49] and was supported by the following entities: National Science Foundation-Center for Applied Tropical Ecology and Conservation (NSF-CREST, HRD0734826), National Institutes of Health-Support of Continuous Research Excellence (NIH SCORE, 2S06GM08102), Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación of Panamá (SENACYT ITE15-030), and Sistema Nacional de Investigación of Panamá (SNI-NM2017-062). Special thanks are due to undergraduates Ana P. Torres-Ocampo, Ivana Serrano-Lachapel, Michael García-Alicea, and Luisa Bernacet for help in the lab.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Corby-Harris V., Pontaroli A. C., Shimkets L. J., Bennetzen J. L., Habel K. E., Promislow D. E. L. Geographical distribution and diversity of bacteria associated with natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73(11):3470–3479. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02120-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox C. R., Gilmore M. S. Native microbial colonization of Drosophila melanogaster and its use as a model of Enterococcus faecalis pathogenesis. Infection and Immunity. 2007;75(4):1565–1576. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01496-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandler J. A., Lang J., Bhatnagar S., Eisen J. A., Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLoS Genetics. 2011;7(9):p. e1002272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broderick N. A., Lemaitre B. Gut-associated microbes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gut Microbes. 2012;3(4):307–321. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebbert M. A., Marlowe J. L., Burkholder J. J. Protozoan and intracellular fungal gut endosymbionts in Drosophila: Prevalence and fitness effects of single and dual infections. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 2003;83(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2011(03)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morais P. B., Lachance M.-A., Rosa C. A. Saturnispora hagleri sp. nov., a yeast species isolated from Drosophila flies in Atlantic rainforest in Brazil. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2005;55(4):1725–1727. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63673-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anagnostou C., Dorsch M., Rohlfs M. Influence of dietary yeasts on Drosophila melanogaster life-history traits. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 2010;136(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2010.00997.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sturtevant A. H. Flies of the genus Drosophila as possible disease carriers. The Journal of Parasitology. 1918;5(2):84–85. doi: 10.2307/3270764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janisiewicz W. J., Conway W. S., Brown M. W., Sapers G. M., Fratamico P., Buchanan R. L. Fate of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on fresh-cut apple tissue and its potential for transmission by fruit flies. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1999;65(1):1–5. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.1-5.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sela S., Nestel D., Pinto R., Nemny-Lavy E., Bar-Joseph M. Mediterranean fruit fly as a potential vector of bacterial pathogens. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(7):4052–4056. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.4052-4056.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller A. Drosophila melanogaster’s history as a human commensal. Current Biology. 2007;17(3):R77–R81. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chartered Institute of Environmental Health, “Pest control procedures in the food industry,” London, pp.52, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landau J. Fruit flies disrupt surgeries at AtlantiCare hospital in Galloway," Press of Atlantic City, 2013 http://www.pressofatlanticcity.com/news/press/atlantic/fruit-flies-disrupt-surgeries-at-atlanticare-hospital-in-galloway/article_2f2a7fe6-3779-11e3-9754-001a4bcf887a.html.

- 14.Irving P., Troxler L., Heuer T. S., et al. A genome-wide analysis of immune responses in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(26):15119–15124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261573998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alarco A.-M., Marcil A., Chen J., Suter B., Thomas D., Whiteway M. Immune-deficient Drosophila melanogaster: a model for the innate immune response to human fungal pathogens. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(9):5622–5628. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lionakis M. S., Kontoyiannis D. P. The growing promise of toll-deficient Drosophila melanogaster as a model for studying Aspergillus pathogenesis and treatment. Virulence. 2010;1(6):488–499. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.6.13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanada Y., Kaya H. K. Insect Pathology. San Diego, Calif, USA: Academic Press; 1993. Associations between insects and nonpathogenic microorganisms. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munyikombo W. D. Potential for transmission of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacterial and parasitic infectious agents by Drosophila sp. (fruit flies) as mechanical vectors. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare. 2014;4(20):154–170. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramírez-Camejo L. A., García-Alicea M., Maldonado-Morales G. Probiotics may protect Drosophila from infection by Aspergillus flavus. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2017;8(4):1624–1632. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banjo A. D., Lawal O. A., Adeduji O. O. Bacteria and fungi isolated from housefly (Musca domestica L.) larvae. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2005;4(8):780–784. [Google Scholar]

- 21.White T. J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA Genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M W. T. J., Gelfand H D., Sninsky J., editors. PCR Protocols: a Guide to Methods and Applications. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press, Inc; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardes M., Bruns T. D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Molecular Ecology. 1993;2(2):113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1993.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisburg W. G., Barns S. M., Pelletier D. A., Lane D. J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. Journal of Bacteriology. 1991;173(2):697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folmer O., Black M., Hoeh W., Lutz R., Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology. 1994;3(5):294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayman P. Diversity, scale and variation of endophytic fungi in leaves of tropical plants. In: MJ B., AK L., TM T.-W., Spencer-Phillips P. T. N., editors. Microbiol Ecology of Aerial Plant Surfaces. UK: CABI Publishing; 2006. pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandler J. A., Eisen J. A., Kopp A. Yeast communities of diverse Drosophila species: Comparison of two symbiont groups in the same hosts. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(20):7327–7336. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01741-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coluccio A. E., Rodriguez R. K., Kernan M. J., Neiman A. M. The yeast spore wall enables spores to survive passage through the digestive tract of Drosophila. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):p. e2873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northrop J. H. The role of yeast in the nutrition of an insect Drosophila. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1917;30:30–181. [Google Scholar]

- 29.King R. C. The effect of yeast on phosphorus uptake by Drosophila. The American Naturalist. 1954;88(840):155–158. doi: 10.1086/281825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry S. M. The significance of microorganisms in the nutrition of insects. Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1962;24(6 Series II):676–683. doi: 10.1111/j.2164-0947.1962.tb01905.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becher P. G., Flick G., Rozpedowska E., et al. Yeast, not fruit volatiles mediate Drosophila melanogaster attraction, oviposition and development. Functional Ecology. 2012;26(4):822–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02006.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen Thanh V., Anh Hai D., Lachance M.-A. Issatchenkia hanoiensis, a new yeast species isolated from frass of the litchi fruit borer Conopomorpha cramerella Snellen. FEMS Yeast Research. 2003;4(1):113–117. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherman J. D., Ingall D., Wiener J., Pryles C. V. Alcaligenes faecalis infection in the newborn. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1960;100(2):212–216. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1960.04020040214009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Högenauer C., Langner C., Beubler E. Klebsiella oxytoca as a causative organism of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(23):2418–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gneiding K., Frodl R., Funke G. Identities of Microbacterium spp. encountered in human clinical specimens. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2008;46(11):3646–3652. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01202-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Looney W. J., Narita M., Mühlemann K. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging opportunist human pathogen. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2009;9(5):312–323. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woo H. I., Lee J. H., Lee S., Ki C., Lee N. Y. Catheter-related bacteremia due to Microbacterium oxydans identified by 16S rRNA sequencing analysis and biochemical characteristics. Korean Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;13(4):p. 173. doi: 10.5145/KJCM.2010.13.4.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooke J. S. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2012;25(1):2–41. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00019-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latgé J.-P. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1999;12(2):310–350. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedayati M. T., Pasqualotto A. C., Warn P. A., Bowyer P., Denning D. W. Aspergillus flavus: human pathogen, allergen and mycotoxin producer. Microbiology. 2007;153(6):1677–1692. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park S. J., Chung C. R., Rhee Y. K., Lee H. B., Lee Y. C., Kweon E. Y. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;186(10):e16–e17. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0263IM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramírez-Camejo L. A., Torres-Ocampo A. P., Agosto-Rivera J. L., Bayman P. An opportunistic human pathogen on the fly: Strains of Aspergillus flavus vary in virulence in Drosophila melanogaster. Medical Mycology. 2014;52(2):211–219. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myt008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klich M. A. Biogeography of Aspergillus species in soil and litter. Mycologia. 2002;94(1):21–27. doi: 10.2307/3761842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coutinho W. M., Suassuna N. D., Luz C. M., Suinaga F. A., Silva O. R. R. F. Bole rot of sisal caused by Aspergillus niger in Brazil. Fitopatologia Brasileira. 2006;31(6):p. 605. doi: 10.1590/S0100-41582006000600014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goswami R. S., Dong Y., Punja Z. K. Host range and mycotoxin production by Fusarium equiseti isolates originating from ginseng fields. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology. 2008;30(1):155–160. doi: 10.1080/07060660809507506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bourret T. B., Kramer E. K., Rogers J. D., Glawe D. A. Isolation of Geotrichum candidum pathogenic to tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) in Washington state. North American Fungi. 2013;8(14):1–7. doi: 10.2509/naf2013.008.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma L.-J., Geiser D. M., Proctor R. H., et al. Fusarium pathogenomics. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2013;67:399–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barros G., Torres A., Chulze S. Aspergillus flavus population isolated from soil of Argentina’s peanut-growing region. Sclerotia production and toxigenic profile. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2005;85(14):2349–2353. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramírez-Camejo L. A., Bayman P. Aspergillosis in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster as a model system. University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras; 2015. [Google Scholar]