Abstract

Nanotechniques that can improve the effectiveness of radiotherapy (RT) by integrating it with multimodal imaging are highly desirable.

Results In this study, we fabricated Bi2S3 nanorods that have attractive features such as their ability to function as contrast agents for X-ray computed tomography (CT) and photoacoustic (PA) imaging as well as good biocompatibility. Both in vitro and in vivo studies confirmed that the Bi2S3 nanoagents could potentiate the lethal effects of radiation via amplifying the local radiation dose and enhancing the anti-tumor efficacy of RT by augmenting the photo-thermal effect. Furthermore, the nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia could effectively increase the oxygen concentration in hypoxic regions thereby inhibiting the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α). This, in turn, interfered with DNA repair via decreasing the expression of DNA repair-related proteins to overcome radio-resistance. Also, RT combined with nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia could substantially suppress tumor metastasis via down-regulating angiogenic factors.

Conclusion In summary, we constructed a single-component powerful nanoagent for CT/PA imaging-guided tumor radiotherapy and, most importantly, explored the potential mechanisms of nanoagent-mediated photo-thermal treatment for enhancing the efficacy of RT in a synergistic manner.

Keywords: multimodal imaging, radiation therapy, hypoxia, DNA repair, synergistic therapy.

Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT), alone or in combination with other treatments, is commonly used in cancer treatment with up to 50% of cancer patients receiving this treatment modality 1, 2. Ionizing irradiation, by reacting with the aqueous environment, induces bursts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are also capable of reacting with important biomolecules such as DNA, proteins, and the fatty-acid moieties of phospholipid cell membranes 3-6. Nevertheless, external RT in which high-energy radiation (X-ray or γ-ray) is used suffers from a series of limitations, including serious injuries to normal tissues 7-9. Furthermore, due to the hypoxic internal tumor microenvironment, tumor cells are less sensitive to ionizing radiation compared with normal cells 10, which is the reason for the resistance or failure of RT. Previous studies have shown that mild hyperthermia treatment can improve the inadequacy of oxygen supply in tumor vascular systems 11-13. In this respect, some nanomaterials hold great promise due to their sensitivity to internal/external redox stimuli 14-16.

A greater local radiation dose can be concentrated by radiosensitizers with strong photoelectric absorbance capacities 17-22. For this purpose, nanomaterials with high atomic number (Z), such as Au, rare earth elements, W, Pt and Bi, have been introduced. Thus, an improvement in the efficacy of RT for cancer cells is achieved while minimizing the radio-toxicity to the surrounding normal tissues 23-25. Among numerous intensifiers, bismuth-based nanomaterials are predicted to be superior to others not only because of their ability to enhance the radiation dose but also because of their use in multimodal imaging 26-30. Bismuth-based nanomaterials such as Bi2S3 nanodots and Bi2Se3 nanoplates have been employed as CT contrast agents due to their high X-ray attenuation capability, which reduces the dose and allows more flexibility in the clinical setting 31-35.

Hypoxia or oxygen deficiency is an essential feature of the microenvironment in solid tumors 36. It is a significant regulative factor in tumor growth 37 and has long been known to have a crucial role in radiotherapy resistance 38-40. Hypoxic tumors are often resistant to traditional cancer therapies, and there is a correlation between tumor hypoxia and advanced stages of malignancy. Previous studies have shown that hyperthermia treatment can also effectively resolve hypoxia. In addition to improving hypoxia, hyperthermia treatment can also effectively suppress DNA repair thereby greatly enhancing the efficacy of RT 41, 42. Therefore, a strong synergistic effect could be efficiently generated by combining hyperthermia and nanomaterials-enhanced RT. In this study, we constructed Bi2S3 nanorods as single-component omnipotent nanoagents and explored their competence as both radio sensitizers and photothermal adsorbing agents for combined PTT and RT. Our work not only introduces Bi-based nanostructures with highly integrated imaging and therapy abilities but also elucidates a detailed mechanism of their synergistic effect.

Results

Synthesis and characterization

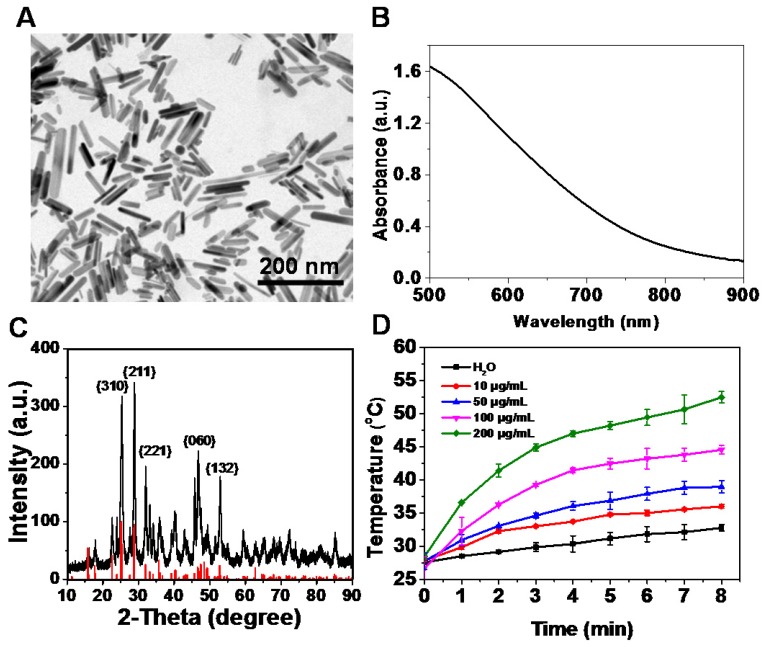

Bi2S3 nanorods were synthesized using the hydrothermal reaction according to the procedure described in previous studies 43-45. The successful fabrication of Bi2S3 nanorods was evidenced by high-resolution transmission electron microscope (TEM) imaging (Figure S1A&B) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDX) (Figure S2). The characterization of the nanoagents by TEM showed average diameters of 10-70 nm in length (Figure 1A). The UV-vis-NIR spectrum of the nanoagents exhibited a broad absorbance band from 700 nm to 1000 nm (Figure 1B) and the XRD pattern demonstrated that all the peaks were well indexed to the orthorhombic Bi2S3 crystal (Figure 1C). When exposed to an 808 nm laser at a power density of 2 W/cm2, the nanoagents exhibited concentration- and time-dependent photothermal effects (Figure 1D). The dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis showed that the hydrodynamic size of the nanorods was 155.4±2.8 nm (Figure S1C) and was almost unchanged in different media within 72 h (Figure S1D). No obvious change was detected for the DLS, UV-vis-NIR absorbance, and XRD characterizations of nanorods upon irradiation by NIR laser for different times (Figure S3A-C) demonstrating good thermal stability. Also, when the nanoagents were subjected to a temperature increase, no obvious change during four repeated laser on/off cycles was observed indicating stable photothermal conversion (Figure S3D).

Figure 1.

Characterization of Bi2S3 nanorods. (A) TEM images (B) UV-vis-NIR absorbance spectra (C) XRD characterization of nanoagents (D) Photothermal curves of different concentrations of Bi2S3 nanorods under 808 nm laser (2.0 W/cm2).

In vitro enhanced radiotherapy combined with photo-thermal treatment

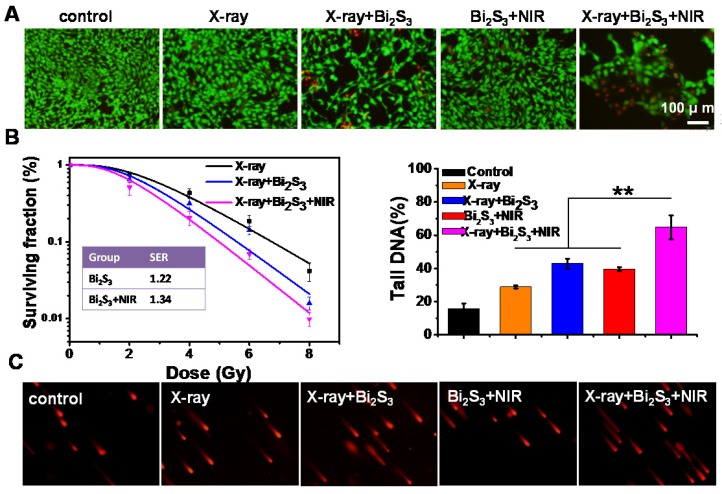

The cell viability assays indicated that Bi2S3 nanorods, even at concentrations up to 200 μg mL-1, caused no obvious cytotoxicity (Figure S4) confirming their good biocompatibility. No obvious influence on the cell viability was observed upon exposure to low-dose X-ray or lower-power NIR laser irradiation, whereas treatment with Bi2S3 nanorods promoted the loss of cell viability. The combination of X-ray and NIR laser irradiation plus treatment with Bi2S3 nanorods resulted in the most significant cell damage causing the death of a large number of cells (Figure 2A). The quantitative analysis of the cell viability confirmed that X-ray irradiation combined with photo-thermal treatment had the greatest cancer cell killing ability (Figure S5).

Figure 2.

In vitro enhanced radiation therapy combined with photothermal treatment. (A) Representative fluorescence images of live (green) and dead (red) cells with various treatments. (B) Clonogenic survival assay of cells treated with X-ray alone, X-ray plus Bi2S3 nanorods, and X-ray plus Bi2S3 nanorods combined with NIR irradiation under a series of radiation doses of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy. (C) Imaging of DNA fragmentation using comet assay in 4T1 cells with different treatments. Histograms correspond to quantification of tail DNA (%). The data are the means and standard deviation from three parallel experiments. More than 50 comets were analyzed in each experiment. P values were calculated by the student's test: **p < 0.01.

Next, a clonogenic survival assay, the gold standard technique for determining cellular radio sensitivity, was performed to evaluate the in vitro efficacy of RT. As expected, the high-Z Bi-based nanoagents exerted a radio-sensitization effect, and nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia synergistically enhanced the efficacy (Figure 2B). Using a linear-quadratic model, the sensitizing enhancement ratio of the nanoagent was calculated to be ~1.22, which upon NIR irradiation was ~1.34. To directly evaluate the DNA damage, a comet assay was conducted, which is a very sensitive method for detecting both single and double-strand DNA breaks in a single cell. As shown in Figure 2C, almost no comet could be observed in control cells. The tail could be observed at low-dose X-ray irradiation and its length increased by 1.5× due to the radio sensitizing effect of Bi. Importantly, upon both X-ray and NIR irradiation, cells treated with nanoagents gave rise to remarkably long stained tails, illustrating the most significant DNA damage (**p< 0.01). The in vitro data presented above indicated that Bi2S3 nanorods had a good radio-sensitizing effect and nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia synergistically strengthened the efficacy of RT.

Dual-modal imaging

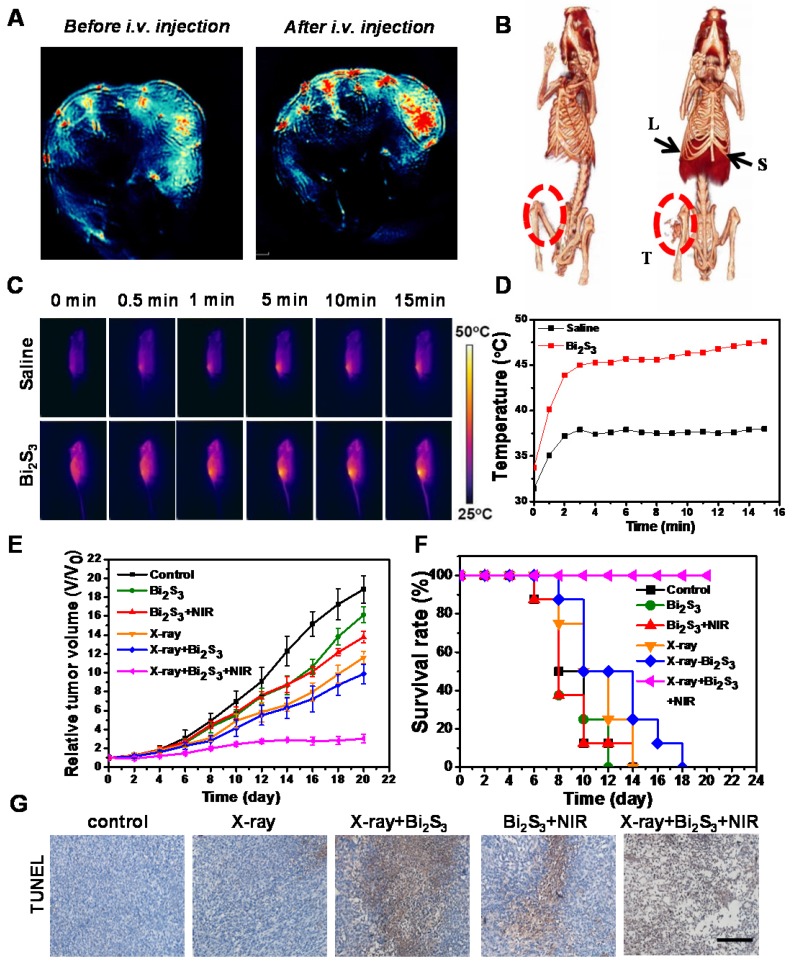

Bi2S3 nanorods with high NIR absorbance are potentially ideal contrast agents for photoacoustic (PA) imaging, which is especially helpful in analyzing the information in the tumor area. We performed PA imaging to understand the distribution of the nanoagents inside tumors. Animal experiments were carried out under protocols approved by Soochow University Laboratory Animal Center. The nanoagents were intravenously (i.v.) injected into the tail vein of tumor-bearing mice, and then the cross-sectional PA signal of tumors was obtained. Before injection, the PA image showed observable but weak signals in the tumor region arising from the tumor blood, whereas PA signals remarkably increased after i.v. injection of the nanoagents indicating the gradual accumulation of Bi2S3 in the tumor sites (Figure 3A). The dynamic MSOT images of tumors at different time points (0.5, 3, 6, and 24 h) showed that the PA signal reached a maximum value and lasted for as long as 24 h (Figure S6).

Figure 3.

Dual-modal imaging and enhanced radiation therapy combined with photothermal treatment in vivo. (A) Photoacoustic images of tumor (B) CT images of tumor-bearing mice before and after i.v. injection of Bi2S3 nanorods: liver (L), spleen (S), and tumor (T) (C) IR thermal images of tumor-bearing mice under 808 nm laser irradiation (0.75 W/cm2) (D) Temperature changes of tumors during laser irradiation (E) Tumor volume growth curves of mice after various treatments (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis (G) TUNEL analysis for apoptosis in tumor sections after different treatments.

The X-ray attenuation property (HU value) of the nanoagents is shown in Figure S7 (iopromide was used as control). The slope of the HU value for the nanoagents was higher than that of a clinically used CT contrast agent (iopromide). The in vivo CT imaging indicated strong tumor contrast demonstrating the superior contrasting efficiency of the Bi2S3 nanorods (Figure 3B). These imaging results collectively confirmed the interesting optical and X-ray absorbance properties of Bi2S3 nanorods as an ideal contrast agent for CT and photoacoustic dual-modal imaging.

In vivo enhanced radiotherapy combined with photo-thermal treatment

We also tested the blood circulation behavior of Bi2S3 nanorods in Balb/c mice bearing 4T1 tumors. According to the two-component pharmacokinetic model, the pharmacokinetic parameters were as follows: t1/2α = 0.4 h; t1/2β = 4.5 h (Figure S8A). Meanwhile, the single-component pharmacokinetic model (C = C0·e-Kt) was also used to calculate the blood half-life as follows: t1/2 = 4.69*ln2 = 3.25 h. Furthermore, we evaluated the biodistribution of Bi2S3 by determining the Bi content in the major organs and tumors. The results revealed that the %ID/g value of tumors was ~2.4% (Figure S8B).

After 15 min of NIR laser irradiation (0.75 W/cm2), the temperature of tumors injected with Bi2S3 increased to ~45 ºC, whereas the tumors in the saline group were not heated (final temperature ~36 ºC) (Figure 3C&D). The tumor growth curves from different groups (Figure 3E) showed that both low-dose X-ray irradiation and nanoagent-based hyperthermia exhibit limited inhibitory effects on the growth of 4T1 solid tumors. In the presence of nanoagents, X-ray irradiation increased tumor growth inhibition attributable to the strong radio sensitizing effect of Bi. Most importantly, in the combination therapy group, remarkably suppressed tumor growth was observed, attributable to the synergistically enhanced therapeutic effect. It is possible that an increased dose of the nanomaterial and/or elevated dose of NIR power density/X-ray radiation dose is needed for complete eradication of tumors.

To compare the overall clinical efficacy as defined by morbidity-free survival, a Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed. Mice in each group were scored when the tumor volume increased five-fold. In this model, we found that the combined treatment was obviously superior to X-ray or NIR alone, further confirming the synergistic effect of nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia on the efficacy of RT treatment (Figure 3F). The anti-tumor efficacy of different treatments was further assessed using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) of the paraffin-embedded tissues (Figure 3G). The combination treatment could induce tumor cell apoptosis to a relatively high level via down-regulating the expression of anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-2 (Figure S9). The activated caspase-3 initiated a caspase-3-dependent mitochondrial pathway to induce apoptosis.

Mechanism of synergistic effect

Based on the preceding experimental observations that Bi-based nanoagents could significantly enhance the therapeutic outcome of radiotherapy together with the photothermal effect, we performed isobologram analysis to determine the interaction between the photothermal therapy and radiotherapy of Bi2S3 nanorods in vitro and in vivo. As shown in Figure S10, the inhibitory effect of PTT and RT on 4T1 cells was synergistic, as evidenced by the fact that data points in the isobologram are far below the line defining additive effects.

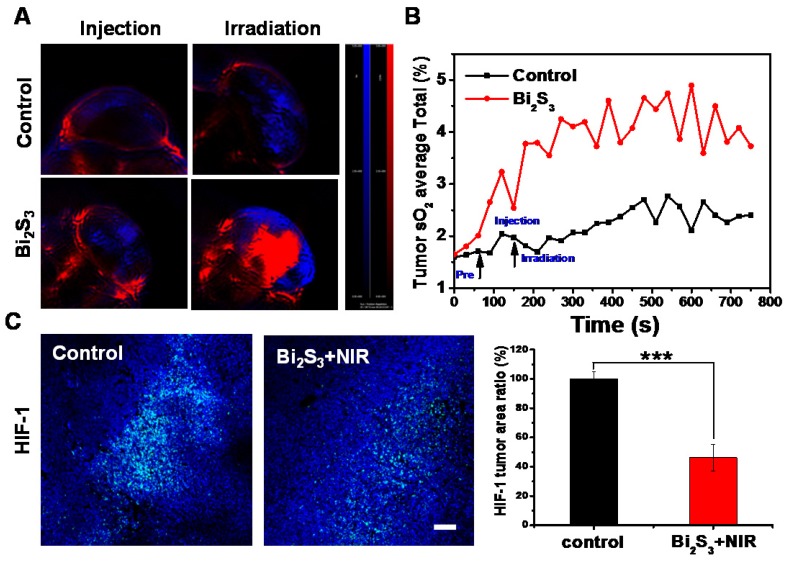

Next, we investigated the possible mechanism of the synergistic effects. Hypoxia is one of the most important factors in the tumor micro-environment and is associated with tumor radio-resistance 46. Previous studies have shown mild hyperthermia to be a radio-sensitizing agent because it could increase the blood flow into the tumor and thus improve the oxygen level in the tumor microenvironment. Thus, the effect of nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia on oxygen saturation within 4T1 tumors was assessed by measuring vascular saturated O2 (sO2). Compared to controls, the injection of nanoagents upon NIR irradiation could not only increase the signal intensity of deoxygenated hemoglobin indicated by the blue color, but also markedly increased the signal intensity of oxygenated hemoglobin indicated by the red color (Figure 4A). By quantifying the average total sO2 in the tumor over time, we observed that sO2 increased promptly by approximately 20% as compared with control (Figure 4B). Hypoxia is known to induce tumor radio resistance 47 through the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). The immunofluorescence assay for HIF revealed that compared to controls nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia significantly inhibited HIF-1α expression, confirming the decreased hypoxia and increased oxygenation (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Effect of photo-thermal treatment on tumor oxygenation. (A) PA images of 4T1 tumors after different treatments by measuring signals at 750 nm and 850 nm representative of deoxygenated hemoglobin and oxygenated hemoglobin (B) Average total sO2 of tumor measured over time (C) Representative images of immunofluorescent staining of HIF-1 from 4T1 tumors after treatment with saline/Bi2S3+NIR (positive expression: bright green regions). Histogram: quantification of HIF-1, determined from classified images (n = 3). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. P values were calculated by the student's test: ***p < 0.001.

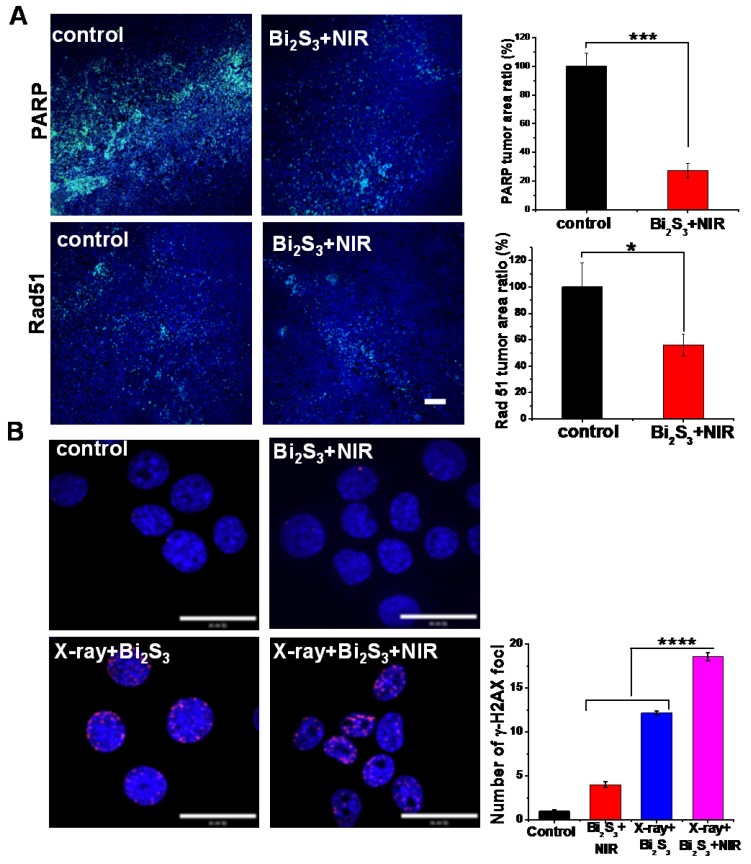

Cancer radiotherapy kills cancer cells mostly by inducing DNA damage, and thus if the damaged lesions are successfully repaired, the cancer cells would survive 48. Of the known DNA repair-related proteins, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is involved in the single strand break repair of DNA 49, 50. Also, as a major homologous recombination protein, Rad 51, dissociates from DNA double strand breaks in response to hyperthermia following exposure to ionizing radiation 51. To verify the effects of mild photothermal heating on DNA repair, immunofluorescence staining for PARP and Rad 51 were performed. As shown in Figure 5A, nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia induced by NIR irradiation significantly decreased the activity of PARP and Rad 51. As compared with the saline control, the tumors treated with nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia showed a 73% and 46% decrease in the expression of PARP and Rad 51, respectively. Moreover, we determined the effect of X-ray on DNA repair and no obvious change was found (Figure S11). This implied that nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia could attenuate irradiation-induced DNA damage because hyperthermia can fix the DNA damage by interfering with the repair of radiation-induced DNA damage.

Figure 5.

Effect of photo-thermal treatment on DNA repair. (A) Representative images of immunofluorescent staining of PARP (upper panels) and rad 51 (lower panels) in continuous sections from 4T1 tumors after treatment with saline/Bi2S3+NIR (positive expression: bright green regions. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. Histograms: quantification of PARP and rad 51 determined from classified images (n = 3). Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean. P values were calculated by the student's test: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. (B) Representative images of γH2AX immunofluorescent staining of 4T1 cells treated with saline/Bi2S3+NIR (γ-H2AX foci are shown as red fluorescence, cell nuclei stained with Hoechst shown as blue fluorescence). Histogram: quantitation of γ-H2AX immunofluorescent foci formation determined from classified images (n = 3). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. P values were calculated by the student's test: ****p < 0.0001.

Among various types of DNA damage, the most deleterious is the DNA double-strand break (DSB) 52, 53. We labeled 4T1 cells with the immunofluorescent label phosphor-histone 2AX (γH2AX), a marker of double-strand DNA breaks 54. As shown in Figure 5B, negligible γH2AX foci were observed in the cells treated with the nanoagents upon NIR irradiation implying limited DNA damage level induced by hyperthermia. However, a remarkably increased level of γH2AX occurred in cells treated with nanoagents upon both X-ray and NIR irradiation compared to those treated with X-ray irradiation alone (shown as red fluorescent spots). These results indicated that DNA repair is heat-sensitive and that nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia significantly increased levels of DNA strand breaks and promoted X-ray irradiation-induced DNA damage.

Anti-invasion and anti-metastasis experiments in vitro and in vivo

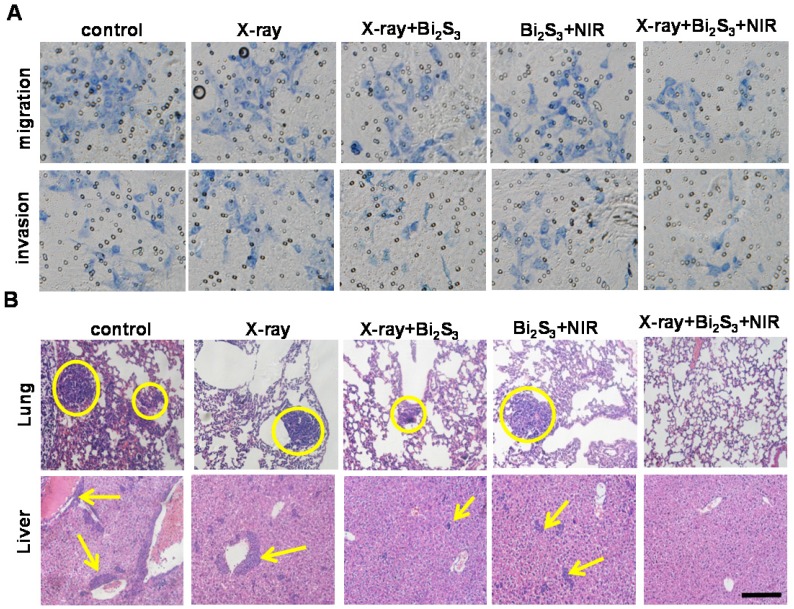

Tumor metastasis is the leading cause of cancer mortality 55 and invasion and metastasis are among the greatest obstacles to successful tumor treatment 56, 57. A significant finding of our study was that the combination treatment of nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia and X-ray/NIR irradiation not only inhibited tumor growth but also greatly suppressed tumor metastasis. To understand the underlying mechanism, transwell assays were performed and the results are presented in Figure 6A&S12. Compared to nanoagent-enhanced X-ray irradiation or nanoagent-based NIR irradiation, the combination treatment significantly reduced the number of migratory and invasive cells. Next, we examined the lungs and livers from mice using H&E staining. The results showed aggressive lung and liver metastases in the organs of control animals, whereas nanoagent-enhanced X-ray irradiation demonstrated superiority in treating metastasis over X-ray irradiation or NIR irradiation alone (Figure 6B&S13). Most significantly, no pulmonary metastasis was observed in mice after combined treatments 58, 59. Furthermore, far fewer blood vessels and lower expression of CD34, a commonly used marker for quantifying angiogenesis, were found in the combination treatment group (Figure S14, first row). The expression levels of the enzyme, MMP-2, and the angiogenic growth factor, VEGF, which are essential for angiogenesis and tumor development 60, 61, showed a similar trend (Figure S14).

Figure 6.

In vitro and in vivo effects of combination treatment on tumor metastasis. (A) Invasion and migration assay of 4T1 cells with different treatments. (B) Micrographs of H&E-stained lung and liver slices collected from different groups of mice. Tumor metastasis sites are highlighted by dashed circles and arrows. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm.

Biosafety and biocompatibility of Bi2S3 nanorods

For the safety evaluation, the plasma levels of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), albumin (ALB), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) for liver toxicity, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine for kidney toxicity were determined and are shown in Table S1. There was no significant difference in the data between Bi2S3 nanorods- and saline-treated groups. Furthermore, the histological analysis of the liver, spleen, and kidney using the hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining displayed no pathological changes compared to treatment with saline (Figure S15).

Discussion

As a common method for cancer therapeutics, the development and application of radio-therapy (RT) are limited by some bottlenecks. RT kills cancer cells mostly by inducing DNA damage, and thus if the damaged lesions are successfully repaired, the cancer cells would survive. Another limitation is of severe damage to surrounding normal tissues. Bismuth-based nanomaterials can improve the efficacy of RT for cancer cells because of several characteristic features such as the ability to enhance the radiation dose, application in multimodal imaging, ability to serve as CT contrast agents, and, above all, good biocompatibility. Exploiting these attractive attributes of bismuth, we have constructed a single-component powerful nanoagent, Bi2S3 nanorods. The strong X-ray attenuation and high NIR absorption make Bi2S3 nanorods attractive as contrast agents for PA and CT imaging, which favors precise positioning of the tumor. Importantly, we have shown that Bi2S3 nanorod-mediated hyperthermia inhibited HIF-1 expression thereby causing decreased hypoxia and increased oxygenation. Cancer radiotherapy kills cancer cells mostly by inducing DNA damage, and thus if the damaged lesions are successfully repaired, the cancer cells would survive. In our study, nanorod-mediated hyperthermia induced by NIR radiation could significantly decrease the activity of DNA repair enzymes, PARP and Rad 51, and substantially interfere with DNA repair, potentiating DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation. Therefore, the integration of RT and nanomaterial-mediated hyperthermia generate a remarkable synergistic therapeutic effect by overcoming the inherent drawbacks of RT.

Tumor metastasis is the leading cause of cancer mortality and invasion and metastasis are among the greatest obstacles to successful tumor treatment. A significant finding of our study was that the combination treatment of nanoagent-mediated hyperthermia and X-ray irradiation not only inhibited tumor growth but also greatly suppressed tumor metastasis. Significantly, our results elucidated the underlying mechanism of inhibition of distant metastasis in our tumor model. We believe that this research provides important proof for nanomaterial-mediated hyperthermia synergistically enhancing the efficacy of RT.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and characterization of Bi2S3 nanoagents

The Bi2S3 nanorods were fabricated by a facial solve thermal method as previously described 42. Tween-20 was employed to functionalize the nanorods, render them water-dispersible, and to improve their biocompatibility. The morphology of Bi2S3 nanorods was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI TECNAI G2, 200 kV). Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu) was utilized to obtain the UV-vis-NIR absorbance spectra. The Rigaku D/max-2500 diffractometer (λ = 1.5418 Å) was used to measure the powder XRD patterns of the dried Bi2S3 nanorods products.

Cell line and culture conditions

Murine breast carcinoma cell line (4T1) was purchased from Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, HyClone), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco BRL), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep, HyClone)) at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Cytotoxicity evaluation and synergistic therapy in vitro

4T1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3×103 per well. After 24 h incubation, the cells had grown to 90% confluence and were distributed in five groups (saline, X-ray, Bi2S3+X-ray, Bi2S3+NIR, Bi2S3+X-ray+NIR). For radiotherapy alone, cells were irradiated with 4 Gy X-ray. For enhanced radiotherapy and hyperthermia, cells were treated with Bi2S3 nanorods (100 μg/mL) for 24 h and then irradiated with X-ray or 808 nm NIR laser (2.0 W/cm2). For the combined group, cells were incubated with Bi2S3 nanorods for 24 h and then subjected to co-exposure to NIR laser and X-ray irradiation. After treatment, 10 μL of CCK-8 was added, the cells were incubated for 2 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm was read using a microplate reader (BioTek, Synergy NEO).

Clonogenic survival assays

4T1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at different numbers (100, 200, 300, 600, 1000 cells) and allowed to adhere overnight. Subsequently, cells were treated with or without Bi2S3 nanorods (100 μg/mL) for 24 h and then irradiated with or without X-ray under different doses of radiation (0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy). Following irradiation, nanoagents were removed and fresh media was added. After 10 days of incubation, cells were washed with PBS before fixation with 100% methanol for 10 min. Methanol was aspirated and colonies were stained with Giemsa dye for 10 min. The number of colonies containing at least 50 cells was determined and the surviving fractions were calculated. The survival curves were plotted using a standard linear quadratic model and triplicate data of each sample were normalized. The sensitization enhancement ratio (SER) was calculated by the linear-quadratic model using origin software. According to the equation, y = exp(-(a*x+b*x2)), where y is the survival fraction, x is the dose of X-ray, 1/a is the mean lethal dose (D0), and SER = D0(with radiosensitizer) / D0(without radiosensitizer).

DNA double-strand breaks

4T1 cells were seeded into 35 mm dishes at a density of 2×104. After 24 h incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, 0.2% Triton X-100 was added to permeate the cells for 10 min. Fixed cells were rehydrated, centrifuged, and immunostained with anti-γ-H2AX antibody (ab81299, Abcam) overnight at 4 °C. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h at 37 °C. Finally, Hoechst (Invitrogen, CA) was added to stain the cell nuclei and the cells were visualized with a confocal laser microscopy (FV1200, OLYMPUS, Japan).

Migration and invasion assays

For the migration assay, serum-free cell suspension was placed into the upper chamber of the 24-well transwell plate containing a polycarbonate membrane (8 μm pore size), and medium containing 10% FBS was placed in the lower chamber. For radiotherapy alone, cells were irradiated with 4 Gy X-ray. For enhanced radiotherapy or hyperthermia, cells were treated with Bi2S3 nanorods (100 μg/mL) for 24 h and then irradiated with X-ray or 808 nm NIR laser (2.0 W/cm2). For combined group, cells were incubated with Bi2S3 nanorods for 24 h and then subjected to co-exposure to NIR laser and X-ray irradiation. After treatment, the cells on the upper chamber were scraped gently and washed with PBS. The cells migrated to the lower surface of the membrane were stained with Giemsa and counted in three independent high-power fields (200×). The invasion assay was performed using a polycarbonate membrane coated with Matrigel and the protocols were the same as for the migration assay.

Tumor model

BALB/c mice were purchased from Chang Zhou Cavens Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd. For the 4T1 tumor model, the right hind legs of BALB/c mice were subcutaneously implanted with 4T1 cells suspended in saline.

CT and PA imaging in vivo

For PA imaging, 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were i.v. injected with 200 μL of Bi2S3 nanorods (10 mg/mL). Subsequently, the signal was recorded on the photoacoustic instrument (MSOT in sight/Vision 256, iThera medical, Germany). Imaging parameters were as follows: the region of interest was 20 mm, and the wavelengths for each slice were from 700 nm to 900 nm. For CT imaging, tumor-bearing mice were injected via the tail vein with 200 μL of Bi2S3 nanorods (15 mg/mL) and a small X-ray CT (Gamma Medica-Ideas) was used to image. To obtain reconstruction images, the filtrated back projection method was performed to reconstruct images, which were analyzed by the Amira 4.1.2 system. The main parameters were as follows: tube voltage 80 kV, effective pixel size 50 μm, tube current 270 μA, field of view 1024 pixels × 1024 pixels.

Synergistic therapy in vivo

When the tumor volume reached approximately 75 mm3, the animals were randomly divided into six groups (n = 8 per group) for various treatments: saline control, X-ray, X-ray + Bi2S3, Bi2S3 +NIR, X-ray + Bi2S3 + NIR. Mice bearing 4T1 tumors were i.v. injected with Bi2S3 nanorods (2 mg/mL, 100 μL) and two hours later irradiated with 808 nm laser (0.75 W/cm2) for 15 min or 4 Gy X-ray (1.23 Gy/min). IR thermal camera (IRS E50 Pro thermal imaging camera) was used to record the temperature of the tumor surface and the tumor size was measured using a caliper every other day. Paraffin sections of tumor tissues were prepared for H&E and TUNEL staining.

Rabbit monoclonal HIF-1alpha antibody (dilution 1:100, Abcam,) and rabbit polyclonal anti-PARP, anti-Rad 51, anti-CD 34, anti-MMP-2, anti-VEGF (dilution 1:100, Abcam) were used for the staining of HIF-1alpha, PARP, Rad 51, CD 34, MMP-2, and VEGF, respectively. Briefly, tumor-bearing mice were treated i.v. with Bi2S3 nanoagents or saline (control). After treatment, the dissected tumor tissues were incubated with various primary antibodies and then Alex 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (dilution 1:200, Abcam) following the vendor's instructions.

Tumor oxygenation measurements

A photoacoustic imaging system (MSOT in sight/Vision 256, iThera Medical, Germany) was used to measure vascular oxygen saturation (sO2) over time before and after i.v. treatment with Bi2S3 nanorods. 750 nm and 850 nm wavelength illumination were selected for deoxygenated and oxygenated hemoglobin, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Blood chemistry analysis of mice, cell viability, X-ray CT images, H&E staining and immuno-histochemical analysis of tumors, the numbers of migratory and invasive cells, mechanism of combination cancer treatments on metastasis and H&E-staining of organs. Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program Grant No. 2014CB931900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (11575123 and 51402203), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province for Young Scholars (BK20140326), Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine and Protection, and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). C. G appreciates the support from the Open Project Program of Key Laboratory for Biomedical Effects of Nanomaterials and Nanosafety, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NSKF201611).

Abbreviations

- RT

radiotherapy

- CT

computed tomography

- PA

photpacoustic

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- PTT

photothermal therapy

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- EDX

energy dispersive spectroscopy

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- NIR

near infrared spectra

- MOST

multispectral optoacoustic tomography scanner

- HU

hounsfield unit

- sO2

saturated O2

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- DSB

double-strand break

- γH2AX

phosphor-histone 2AX

- H&E staining

hematoxylin-eosin staining

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase-2

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- ALB

albumin

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- DMEM

dulbecco's modified eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- CCK-8

cell counting kit-8

- SER

sensitization enhancement ratio.

References

- 1.Harrington K, Billingham L, Brunner T, Burnet N, Chan C, Hoskin P. et al. Guidelines for preclinical and early phase clinical assessment of novel radiosensitisers. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:628–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falk S. Principles of cancer treatment by radiotherapy. Surgery (Oxford) 2006;24:62–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tubiana M. Introduction to radiobiology. CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azzam EI, Jay-Gerin JP, Pain D. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Lett. 2012;327:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noda A, Hirai Y, Hamasaki K, Mitani H, Nakamura N, Kodama Y. Unrepairable DNA double-strand breaks that are generated by ionising radiation determine the fate of normal human cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5280–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santivasi WL, Xia F. Ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage, response, and repair. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:251–9. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M, Atkinson RL, Rosen JM. Selective targeting of radiation-resistant tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:3522–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910179107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meijer TW, Kaanders JH, Span PN, Bussink J. Targeting hypoxia, HIF-1, and tumor glucose metabolism to improve radiotherapy efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5585–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CC, Reardon MA, Ball BZ, Chen CJ, Yen CP, Xu Z. et al. The predictive value of magnetic resonance imaging in evaluating intracranial arteriovenous malformation obliteration after stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:136–44. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS141565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Zhang J, Wang X, Li Y, Chen Y, Li K. et al. HIF-1 and NDRG2 contribute to hypoxia-induced radioresistance of cervical cance hela cells. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1985–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song CW, Park H, Griffin RJ. Improvement of tumor oxygenation by mild hyperthermia. Radiat Res. 2001;155:515–28. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0515:iotobm]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song C, Shakil A, Osborn J, Iwata K. Tumour oxygenation is increased by hyperthermia at mild temperatures. Int J Hyperthermia. 2009;25:91–5. doi: 10.1080/02656730902744171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata K, Shakil A, Hur W, Makepeace C, Griffin R, Song C. Tumour Po2 can be increased markedly by mild hyperthermia. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1996;27:S217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan W, Bu W, Shen B, He Q, Cui Z, Liu Y. et al. Intelligent MnO2 nanosheets anchored with upconversion nanoprobes for concurrent pH-/H2O2-responsive UCL imaging and oxygen-elevated synergetic therapy. Adv Mater. 2015;27:4155–61. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian J, Chen J, Ge C, Liu X, He J, Ni P. et al. Synthesis of PEGylated ferrocene nanoconjugates as the radiosensitizer of cancer cells. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27(6):1518–24. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q, Feng L, Liu J. Zhu W, Dong Z, Wu Y, et al. Intelligent albumin-MnO2 nanoparticles as pH-/H2O2-Responsive dissociable nanocarriers to modulate tumor hypoxia for effective combination therapy. Adv Mater. 2016;27:4155–61. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dou Y, Guo Y, Li X, Wang S, Wang L, Lv G. et al. Size-Tuning Ionization To Optimize GoldNanoparticles for Simultaneous Enhanced CT Imaging and Radiotherapy. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2536–48. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Zhang X, Zhu M, Lin G, Liu J, Zhou Z. et al. PEGylated Au@Pt Nanodendrites as Novel Theranostic Agents for CT Imaging and Photothermal/Radiation Synergistic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:279–85. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yong Y, Cheng X, Bao T, Zu M, Yan L, Yin W. et al. Tungsten sulfide quantum dots as multifunctional nanotheranostics for in vivo dual-modal image-guided photothermal/radiotherapy synergistic therapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9:12451–63. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao Q, Zheng X, Bu W, Ge W, Zhang S, Chen F. et al. A core/satellite multifunctional nanotheranostic for in vivo imaging and tumor eradication by radiation/photothermal synergistic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13041–8. doi: 10.1021/ja404985w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng Y, Li E, Cheng X, Zhu J, Lu S, Ge C. et al. Facile preparation of hybrid core-shell nanorods for photothermal and radiation combined therapy. Nanoscale. 2016;8:3895–9. doi: 10.1039/c5nr09102k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wen L, Chen L, Zheng S, Zeng J, Duan G, Wang Y. et al. Ultrasmall biocompatible WO3-x nanodots for multi-modality imaging and combined therapy of cancers. Adv Mater. 2016;28:5072–9. doi: 10.1002/adma.201506428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Zaki A, Joh D, Cheng Z, De Barros ALB, Kao G, Dorsey J. et al. Gold-loaded polymeric micelles for computed tomography-guided radiation therapy treatment and radiosensitization. ACS Nano. 2014;8:104–12. doi: 10.1021/nn405701q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su XY, Liu PD, Wu H, Gu N. Enhancement of radiosensitization by metal-based nanoparticles in cancer radiation therapy. Cancer Biol Med. 2014;11:86–91. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song G, Chen Y, Liang C, Yi X, Liu J, Sun X. et al. Catalase-loaded TaOx nanoshells as bio-nanoreactors combining high-z element and enzyme delivery for enhancing radiotherapy. Adv Mater. 2016;28:7143–8. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabin O, Perez JM, Grimm J, Wojtkiewicz G, Weissleder R. An X-ray computed tomography imaging agent based on long-circulating bismuth sulphide nanoparticles. Nat Mater. 2006;5:118–22. doi: 10.1038/nmat1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Zheng X, Yan L, Zhou L, Tian G, Yin W. et al. Bismuth sulfide nanorods as a precision nanomedicine for in vivo multimodal imaging-guided photothermal therapy of tumor. ACS Nano. 2015;9:696–707. doi: 10.1021/nn506137n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S, Salavati-Niasari M. Nanocrystalline Pr6O11: synthesis, characterization, optical and photocatalytic properties. New J Chem. 2015;39:3948–55. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S, Salavati-Niasari M, Hamadanian M. Praseodymium oxide nanostructures: novel solvent-less preparation, characterization and investigation of their optical and photocatalytic properties. RSC Adv. 2015;5:33792–800. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S, Salavati-Niasari M, Zinatloo-Ajabshir Z. Nd2Zr2O7-Nd2O3 nanocomposites: new facile synthesis, characterization and investigation of photocatalytic behaviour. Mater Lett. 2016;180:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ai K, Liu Y, Liu J, Yuan Q, He Y, Lu L. Large- scale synthesis of Bi2S3 nanodots as a contrast agent for in vivo X-ray computed tomography imaging. Adv Mater. 2011;23:4886–91. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinsella JM, Jimenez RE, Karmali PP, Rush AM, Kotamraju VR, Gianneschi N. et al. X-Ray computed tomography imaging of breast cancer by using targeted peptide-labeled bismuth sulfide nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:12308–11. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salavati-Niasari M, Bazarganipour M, Davar F. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of bismuth selenide nanorods via a co-reduction route. Inorganica Chim Acta. 2011;365:61–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu J, Wang J, Wang X, Wang X, Zhu J, Yang Y. et al. Facile synthesis of magnetic core-shell nanocomposites for MRI and CT bimodal imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;34:6905–10. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00775e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salavati-Niasari M, Ghanbari D, Davar F. Synthesis of different morphologies of bismuth sulfide nanostructures via hydrothermal process in the presence of thioglycolic acid. J Alloys Compd. 2009;488:442–7. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y, Lin Q, Glazer PM, Yun Z. Hypoxic tumor microenvironment and cancer cell differentiation. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:425–34. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris AL. Hypoxia-a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Overgaard J. Hypoxic modification of radiotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown JM. Tumor hypoxia in cancer therapy. Methods Enzymol. 2007;435:295–321. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)35015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugrue T, Lowndes NF, Ceredig R. Hypoxia enhances the radioresistance of mouse mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2188–200. doi: 10.1002/stem.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Awady R, Dikomey E, Dahm-Daphi J. Heat effects on DNA repair after ionising radiation: hyperthermia commonly increases the number of non-repaired double-strand breaks and structural rearrangements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1960–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oei AL, Vriend LE, Crezee J, Franken NA, Krawczyk PM. Effects of hyperthermia on DNA repair pathways: one treatment to inhibit them all. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:165–178. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0462-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng X, Shi J, Bu Y, Tian G, Zhang X, Yin W. et al. Silica-coated bismuth sulfide nanorods as multimodal contrast agents for a non-invasive visualization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nanoscale. 2015;7:12581–91. doi: 10.1039/c5nr03068d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qazvini NT, Zinatloo S. Synthesis and characterization of gelatin nanoparticles using CDI/NHS as a non-toxic cross-linking system. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22:63–9. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babu R, Thomas S, Hazzard MA, Friedman AH, Sampson JH, Adamson C. et al. Worse outcomes for patients undergoing brain tumor and cerebrovascular procedures following the ACGME resident duty-hour restrictions. J Neurosurg. 2014;121:262–76. doi: 10.3171/2014.5.JNS1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffin R J, Ogawa A, Williams BW, Song CW. Hyperthermic enhancement of tumor radiosensitization strategies. Immunol Invest. 2005;34:343–59. doi: 10.1081/imm-200066270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jain S, Coulter JA, Butterworth KT, Hounsell AR, McMahon SJ, Hyland WB. et al. Gold nanoparticle cellular uptake, toxicity and radiosensitisation in hypoxic conditions. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:342–7. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hosoya N, Miyagawa K. Targeting DNA damage response in cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:370–88. doi: 10.1111/cas.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robu M, Shah RG, Petitclerc N, Brind'Amour J, Kandan-Kulangara F, Shah GM. Role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in the removal of UV-induced DNA lesions by nucleotide excision repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:1658–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209507110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher AE, Hochegger H, Takeda S, Caldecott KW. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 accelerates single-strand break repair in concert with poly (ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. Mol Cell Bio. 2007;27:5597–605. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02248-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sak A, Stueben G, Groneberg M, Bocker W, Stuschke M. Targeting of Rad51-dependent homologous recombination: implications for the radiation sensitivity of human lung cancer cell line. Br JCancer. 2005;92:1089–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Y, Caron P, Legube G, Paull TT. Quantitation of DNA double-strand break resection intermediates in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;43:e19–e19. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huhn D, Bolck HA, Sartori AA. Targeting DNA double-strand break signalling and repair: recent advances in cancer therapy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:523–9. doi: 10.4414/smw.2013.13837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuo LJ, Yang LX. γ-H2AX-a novel biomarker for DNA double-strand breaks. In Vivo. 2008;22:305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin TA, Ye L, Sanders AJ, Lane J, Jiang WG. Cancer invasion and metastasis: molecular and cellular perspective. 2000.

- 56.Van ZijlF, Krupitza G, Mikulits W. Initial steps of metastasis: cell invasion and endothelial transmigration. mutat. Mutat Res. 2011;728:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nico B, Benagiano V, Mangieri D, Maruotti N, Vacca A, Ribatti D. et al. Evaluation of microvascular density in tumors, Pro And Contra. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:601–7. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leon SP, Folkerth RD, Black PM. Microvessel density is a prognostic indicator for patients with astroglial brain tumors. Cancer. 1996;77:362–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960115)77:2<362::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferrara N, Alitalo K. Clinical applications of angiogenic growth factors and their inhibitors. Nat Med. 1999;5:1359–64. doi: 10.1038/70928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rundhaug JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:267–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Blood chemistry analysis of mice, cell viability, X-ray CT images, H&E staining and immuno-histochemical analysis of tumors, the numbers of migratory and invasive cells, mechanism of combination cancer treatments on metastasis and H&E-staining of organs. Supplementary figures and tables.