Abstract

Aims

We aimed to explore the burden of frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) associated with myocardial dysfunction in patients with outflow tract arrhythmia (OTA). We hypothesized that this threshold is lower than the previously suggested threshold of 24 000 PVCs/24 h (24%PVC) when systolic function is assessed by strain echocardiography. Furthermore, we aimed to characterize OTA patients with malignant arrhythmic events.

Methods and results

We included 52 patients referred for OTA ablation (46 ± 12 years, 58% female). Left ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) and mechanical dispersion were assessed by speckle tracking echocardiography. A subset underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. PVC burden (%PVC) was assessed by Holter recording. Sinus rhythm QRS duration and PVC QRS duration were recorded from electrocardiogram, and the ratio was calculated (PVC QRS duration / sinus rhythm QRS duration). Median %PVC was 7.2 (0.2–60.0%). %PVC correlated with GLS (R = 0.44, P = 0.002) and with mechanical dispersion (R = 0.48, P < 0.001), but not with ejection fraction (R = 0.22, P = 0.12). %PVC was higher in patients with impaired systolic function by GLS (worse than −18%) compared with patients with normal function (22% vs. 5%, P = 0.001). Greater than 8%PVC optimally identified patients with abnormal GLS (area under the curve 0.79). Serious arrhythmic events occurred in 11/52 (21%) patients characterized by high QRS ratios (1.56 vs. 1.91, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

More than 8%PVC was associated with impaired systolic function by GLS, which is a lower threshold than previously reported. Patients with serious arrhythmic events had higher QRS ratios, which may represent a more malignant phenotype of OTA.

Keywords: Outflow tract arrhythmia, RVOT, Premature ventricular contractions, Heart failure, Echocardiography, Global longitudinal strain

Introduction

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are a frequent complaint in the adult population and a common cause of cardiological referral. Frequent PVCs, non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), and ventricular tachycardia (VT) occurring in the absence of structural heart disease, channelopathy, and metabolic disturbances are defined as idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias. These arrhythmias most commonly arise from the ventricular outflow tracts. More than 80% of outflow tract arrhythmias (OTAs) originate from the right ventricular (RV) outflow tract (RVOT) and are characterized by a dominating left bundle branch block configuration and inferior electrical axis on the electrocardiogram (ECG).1 VTs originating from the outflow tract area are usually monomorphic, well tolerated, and rarely thought to cause syncope or sudden cardiac death. However, the notion of a benign disease has been repeatedly challenged.2 Very frequent PVCs from the outflow tract area can impair myocardial function and may cause dilated cardiomyopathy.3, 4, 5, 6 A PVC burden (%PVC) of >24% (almost one in four heartbeats, and approximately 24 000 PVCs in 24 h) has been associated with impaired myocardial function as measured by left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF).7

Strain echocardiography can detect early and subtle myocardial dysfunction and adds prognostic value in patients with cardiomyopathies.8, 9 LV global longitudinal strain (GLS) is an accurate and sensitive marker of systolic dysfunction.10, 11 Systolic dysfunction due to frequent PVCs has not been evaluated by GLS.

We aimed to identify the %PVC associated with impaired myocardial function in patients with idiopathic OTA. We hypothesized that the threshold is lower than previously suggested when impairment is measured by strain echocardiography. As a secondary objective, we wanted to explore ECG and imaging characteristics of the subset of OTA patients with serious arrhythmic events.

Methods

Population and clinical evaluation

We retrospectively included patients with OTA and frequent PVCs referred to the Department of Cardiology, Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet, between 2011 and 2015. Patients with monomorphic PVCs with left bundle branch block configuration and inferior electrical axis were included if 24 h Holter recordings and echocardiography prior to the ablation procedure was available. We excluded patients with underlying cardiomyopathy, channelopathy, overt structural heart disease, or polymorphic PVCs. In particular, we carefully excluded patients who fulfilled an arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) diagnosis according to the revised task force criteria of 2010.12 Data from clinical examinations, history of syncope of suspected cardiac origin, comorbidities, and medications were recorded.

Written informed consent was given by all study participants. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical Research Ethics in Norway.

Electrocardiogram

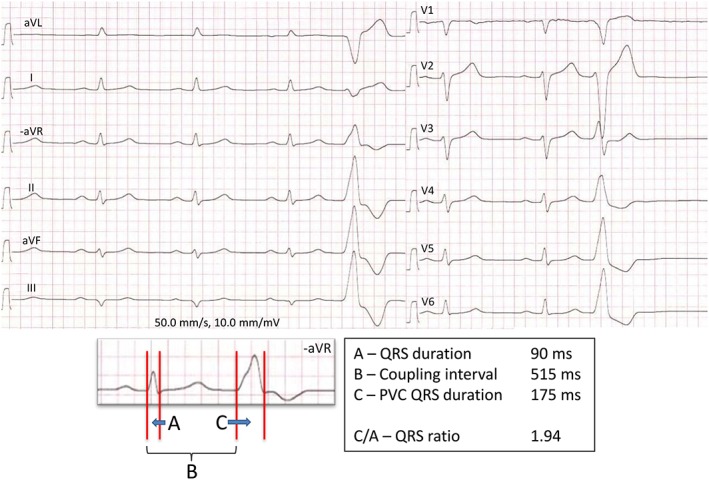

On the 12‐lead ECG, we manually measured the sinus rhythm (SR) QRS duration and the PVC QRS duration in the lead with the widest QRS complex. The QRS ratio was calculated by dividing the PVC QRS duration by the QRS duration of the preceding normally conducted sinus beat (Figure 1 ). A QRS ratio of ≥1.9 was defined as suggestive of an RVOT‐free wall PVC origin, and a lower QRS ratio was suggestive of a septal RVOT origin as previously described.13 Furthermore, we considered an LV outflow tract PVC origin when the PVCs had an early precordial R/S transition, with R/S amplitude index >0.3 in V1 or V2. The coupling interval was measured from the initial Q/R wave of the preceding sinus beat to the Q/R start of the subsequent PVC (Figure 1 ). ECG interpretations were blinded to clinical data.

Figure 1.

Outflow tract arrhythmia on the electrocardiogram. Twelve‐lead electrocardiogram of patient X with outflow tract arrhythmia and history of sustained ventricular tachycardia and syncope. There is dominating left bundle branch block morphology and inferior electrical axis of the premature ventricular contraction (PVC), and the QRS ratio, calculated by dividing the PVC QRS duration (C) by the sinus rhythm QRS duration (A), is > 1.9. This is suggestive of a right ventricular outflow tract‐free wall PVC origin. By Holter recording, this patient had 33% PVCs.

Holter recording

A %PVC was assessed by a 24 h Holter recording performed at the same clinical visit as the echocardiography, and was expressed as the percentage of PVCs to total recorded beats. Sustained and non‐sustained VTs were categorized as present or absent, defining sustained VT as lasting >30 s and NSVT as three or more consecutive PVCs ≥100 beats per minute, self‐terminating within 30 s.14 We defined serious arrhythmic events as sustained VT requiring acute medical attention or syncope of suspected cardiac origin, and recorded them retrospectively. Occurrence of NSVT alone without syncope was not defined as a serious arrhythmic event.

Echocardiography

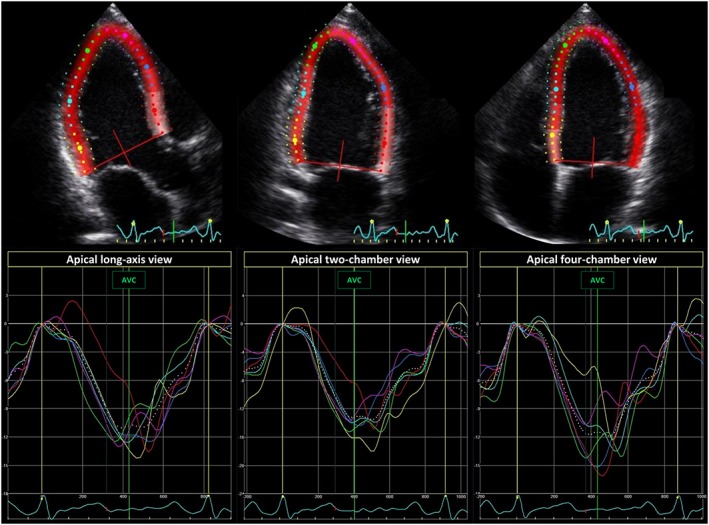

Echocardiography was performed with Vivid 7 or Vivid E9 scanners (GE Healthcare, Horten, Norway) with offline data analysis (EchoPac® version 112 GE Healthcare) blinded to clinical data. Only loops from sinus beats with normal conduction were analysed. EF was calculated by modified Simpson's biplane method. An abnormal EF was defined as <52% in males and <54% in females.15 LV dimensions were obtained in 2D mode, and a dilated LV was defined as LV internal diameter in diastole (LVIDd) >58 mm in males and >52 mm in females.15 We further assessed myocardial function by speckle‐tracking echocardiography‐derived GLS defined as the peak longitudinal strain from three apical views averaged in a 16‐segment LV model10 (Figure 2 ). We defined GLS worse than −18% as abnormal, based on a previous meta‐analysis which included 2597 subjects.16 Mechanical dispersion was expressed by the standard deviation of the time from R on ECG to peak strain in 16 LV segments.9 Measurements from the RV included proximal RVOT diameter from the parasternal short‐axis view, basal RV diameter, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion,15 and RV longitudinal strain (RVLS) calculated from three free wall RV segments.17, 18, 19

Figure 2.

Global longitudinal strain. Echocardiographic strain curves from the three apical views of patient X with 33% premature ventricular contractions. Global longitudinal strain (GLS) was calculated as the average peak longitudinal strain in 16 left ventricular segments. Patient X had a GLS of −14.3%.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) was performed in a subset of patients (n = 22) as a part of the clinical evaluation and exclusion of ARVC, using a 1.5 Tesla unit (Magnetom Sonata, Vision Plus or Avanto Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a phased array body coil as previously described.20 LV and RV volumes and EFs were recorded, as well as the presence of late gadolinium enhancement or contraction abnormalities.

Statistics

Parametric data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared by unpaired Student's t‐test or χ2. %PVC and coupling interval were not normally distributed and presented as median (range) and compared by Mann–Whitney U test. We defined GLS worse than −18% as the primary endpoint of the study, and the occurrence of serious arrhythmic events as the secondary endpoint. Associations between %PVC and measures of LV and RV function were evaluated by linear regression‐derived Pearson's correlation. Significant markers (P < 0.05) of GLS worse than −18% and of serious arrhythmic events in univariable analyses were analysed in multivariable logistic regression models, in addition to sex and age which were forced in (IBM SPSS statistics 21). Multicollinearity was observed between ECG parameters associated with serious arrhythmic events, and only the QRS ratio was included in multivariable analyses. Receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curves were constructed for the ability of %PVC to discriminate between patients with normal and abnormal myocardial function. Coordinates from the ROC curves closest to the upper left corner defined optimal cut‐off values. All P‐values were two‐sided, and values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

A total of 135 patients with frequent outflow tract PVCs and/or VT were referred for ablation therapy to the Department of Cardiology at Oslo University Hospital. Of these, 76 had both a Holter recording and an echocardiographic examination available prior to the ablation procedure. Fourteen patients were excluded because of a concomitant cardiovascular condition [eight fulfilled criteria for probable (>1 minor criterion) ARVC, two were pregnant, one had atrial fibrillation, one moderate to severe mitral regurgitation, one KCNH2 mutation, and one had pre‐excitation on ECG], and five patients were excluded because of ECG morphology not suggestive of OTA. In four patients, the echocardiographic examination was excluded because of bigeminal PVCs, and one patient was excluded due to poor echocardiographic image quality.

In total, 52 patients (age 46 ± 12 years, 58% female) were included (Table 1). Five patients had been admitted and treated for sustained VT, and four of these had also experienced cardiac syncope. Another six patients had syncope of suspected cardiac origin, of which three had NSVT. Thus, 11 patients had experienced serious events according to our definition. Thirty patients (58%) had documented NSVT.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 52 patients with outflow tract arrhythmia and normal and abnormal left ventricular (LV) global longitudinal strain (GLS)

| All patients n = 52 | LV GLS better than −18% n = 37 | LV GLS worse than −18% n = 15 | P‐value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 29 (56) | 24 (65) | 5 (33) | 0.04 | 0.7 (0.1–4.3) | 0.70 |

| Age, years | 46.2 ± 11.7 | 43.4 ± 13.8 | 48.1 ± 8.9 | 0.45 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.96 |

| BSA, m2 (by 0.1 increase) | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.01 | 2.1 (1.1–4.0) | 0.02 |

| Syncope, n (%) | 10 (20) | 9 (24) | 1 (7) | 0.15 | ||

| VT, n (%) | 5 (10) | 5 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.14 | ||

| NSVT, n (%) | 30 (58) | 21 (57) | 9 (60) | 0.83 | ||

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 43 (83) | 31 (84) | 12 (80) | 0.75 | ||

| Flecainide, n (%) | 10 (19) | 7 (19) | 3 (20) | 0.93 | ||

| ECG parameters | ||||||

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 63 ± 12 | 62 ± 11 | 67 ± 11 | 0.12 | ||

| PVC, % | 7 (0, 60) | 5 (0, 46) | 22 (3, 60) | 0.001 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.008 |

| PVC QRS, ms | 145 ± 18 | 144 ± 19 | 148 ± 15 | 0.55 | ||

| Sinus QRS, ms | 90 ± 11 | 89 ± 11 | 92 ± 10 | 0.35 | ||

| QRS ratio | 1.64 ± 0.28 | 1.65 ± 0.30 | 1.61 ± 0.21 | 0.71 | ||

| Coupling interval, ms | 455 (300, 840) | 470 (320, 840) | 440 (300, 520) | 0.37 | ||

| RVOT‐free wall origin, n (%) | 9 (18) | 8 (23) | 1 (7) | 0.18 | ||

| Imaging | ||||||

| LVEF, % | 56 ± 6 | 58 ± 5 | 52 ± 6 | 0.002 | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.04 |

| GLS, % | −20.2 ± 2.8 | −21.6 ± 2.0 | −16.8 ± 1.0 | n.a. | ||

| LVIDd, mm | 54 ± 5 | 53 ± 5 | 57 ± 5 | 0.03 | 0.8 (0.7–1.1) | 0.32 |

| TAPSE, mm | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 21 ± 4 | 0.19 | ||

| RVD, mm | 39 ± 5 | 39 ± 5 | 38 ± 4 | 0.76 | ||

| RVOT, mm | 33 ± 5 | 33 ± 5 | 35 ± 4 | 0.24 | ||

| RVLS, % | −27.6 ± 5.1 | −27.8 ± 5.4 | −27.1 ± 4.3 | 0.61 | ||

| CMR LVEF (n = 22), % | 53 ± 6 | 52 ± 5 | 54 ± 8 | 0.52 | ||

| CMR RVEF (n = 22), % | 51 ± 3 | 51 ± 3 | 52 ± 3 | 0.37 |

BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter in diastole; NSVT, non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia; PVC, premature ventricular contractions; RVD, basal right ventricular diameter; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; RVLS, right ventricular longitudinal strain; RVOT, proximal right ventricular outflow tract diameter in parasternal short‐axis view; TAPSE, tricuspid annulus plane systolic excursion; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Values are mean ± SD or median (range) unless stated otherwise. P‐values are calculated by unpaired Student's t‐test, χ2, or Mann–Whitney U test. Odds ratio and adjusted P‐values by multivariable logistic regression.

Holter recordings and electrocardiogram

Resting heart rate was 64 ± 12 beats per minute. The median %PVC from Holter recordings was 7.2 (range 0.2–60.0%). %PVC was higher in patients with impaired systolic function by GLS (worse than −18%) compared with patients with normal function (22% vs. 5% P = 0.001). On 12‐lead ECGs, mean PVC QRS duration was 145 ± 18 ms and the SR QRS duration was 90 ± 11 ms, generating a mean QRS ratio of 1.64 ± 0.28. Using the QRS morphology and ratio to suggest origin of the ectopy, nine patients had RVOT‐free wall PVC origin and 41 had septal RVOT origin. Two patients had ECGs suggestive of LV outflow tract arrhythmia.

Myocardial function and premature ventricular contraction burden

Mean EF in all patients was 56 ± 6%, and GLS was −20.2 ± 2.8%. %PVC was a marker of worse GLS, independently of age, sex, EF, LVIDd, and body surface area. By ROC analyses, a %PVC >8 optimally detected patients with a GLS worse than −18%, with a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 70%, and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66–0.92] (Table 2). %PVC >10 optimally detected patients with abnormal EF (<52% and <54%) (AUC = 0.75, 95% CI 0.62–0.89). %PVC could not identify an abnormal LVIDd (AUC = 0.65, 95% CI 0.49–0.80).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 52 patients with outflow tract arrhythmia, with %PVC < 8 and > 8

| %PVC < 8 | %PVC > 8 | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 28 | n = 24 | ||

| Female, n (%) | 19 (68) | 10 (42) | 0.06 |

| Age, years | 43.9 ± 11.2 | 48.8 ± 12.0 | 0.13 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.28 |

| Syncope, n (%) | 6 (21) | 4 (17) | 0.67 |

| VT, n (%) | 4 (14) | 1 (4) | 0.23 |

| NSVT, n (%) | 14 (50) | 16 (67) | 0.23 |

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 25 (89) | 18 (75) | 0.18 |

| Flecainide, n (%) | 8 (29) | 2 (8) | 0.07 |

| ECG parameters | |||

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 60 ± 9 | 67 ± 13 | 0.02 |

| PVC, % | 3 (0, 8) | 22 (8, 60) | n.a. |

| PVC QRS, ms | 145 ± 18 | 145 ± 18 | 0.97 |

| Sinus QRS, ms | 89 ± 11 | 92 ± 11 | 0.34 |

| QRS ratio | 1.67 ± 0.32 | 1.60 ± 0.22 | 0.36 |

| Coupling interval, ms | 455 (320, 840) | 460 (300, 710) | 0.59 |

| PVC free wall origin, n (%) | 7 (27) | 2 (8) | 0.09 |

| Imaging | |||

| LVEF, % | 58 ± 4 | 54 ± 7 | 0.004 |

| GLS, % | −21.6 ± 2.5 | −18.6 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| LVIDd, mm | 52 ± 5 | 56 ± 4 | 0.01 |

| MD, ms | 37 ± 13 | 50 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| TAPSE, mm | 23 ± 3 | 22 ± 4 | 0.11 |

| RVD, mm | 38 ± 5 | 39 ± 5 | 0.33 |

| RVOT, mm | 32 ± 5 | 34 ± 4 | 0.16 |

| RVLS, % | −28.2 ± 5.7 | −27.0 ± 4.3 | 0.40 |

| CMR LVEF (n = 22), % | 55 ± 5 | 50 ± 6 | 0.06 |

| CMR RVEF (n = 22), % | 52 ± 2 | 51 ± 4 | 0.40 |

BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter in diastole; MD, mechanical dispersion; NSVT, non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia; PVC, premature ventricular contractions; RVD, basal right ventricular diameter; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; RVLS, right ventricular longitudinal strain; RVOT, proximal right ventricular outflow tract in parasternal short‐axis view; TAPSE, tricuspid annulus plane systolic excursion; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Values are mean ± SD or median (range) unless stated otherwise. P‐values are calculated by unpaired Student's t‐test, χ2, or Mann–Whitney U test.

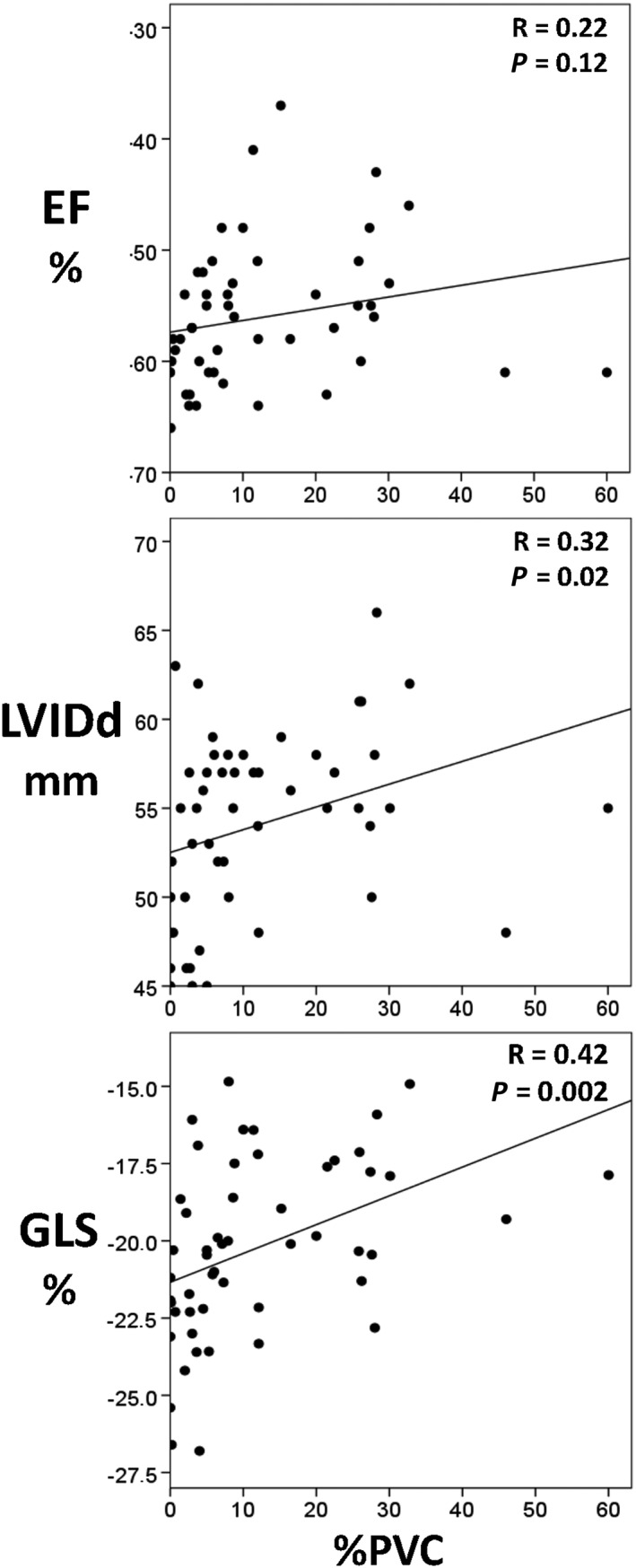

There was a moderate, significant correlation between higher %PVC and worse GLS (R = 0.44, P = 0.002) (Figure 3 ) and increased mechanical dispersion (R = 0.48, P < 0.001), while no significant correlation was found between %PVC and EF (R = 0.22, P = 0.12). Mechanical dispersion was more pronounced in patients with %PVC > 8 (Table 2). %PVC correlated weakly with LVIDd (R = 0.32, P = 0.02) and RVOT diameter (R = 0.37, P = 0.02). No correlations were observed between %PVC and other RV measures [RVLS (R = 0.05, P = 0.74), RV diameter (R = 0.05, P = 0.73), or tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (R = 0.09, P = 0.51)].

Figure 3.

The correlation between premature ventricular contractions and left ventricular function. Correlation plots between the burdens of premature ventricular contractions (%PVC) as evaluated on a 24 h Holter recording and presented as a percentage of total recorded heart beats (X‐axis) and parameters of myocardial function derived from echocardiography on the Y‐axis. EF, ejection fraction; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter in diastole.

Resting heart rate did not differ between the patients with normal and abnormal myocardial function determined by GLS (P = 0.15) but was slightly higher in patients with >8%PVC (P = 0.02). There was no correlation between resting heart rate and GLS or EF (R = 0.21, P = 0.14, and R = 0.14, P = 0.32, respectively).

As expected, there was a significant correlation between GLS and EF (R = 0.53, P < 0.001). Furthermore, LVIDd and GLS correlated (R = 0.37, P = 0.007), as well as LVIDd and EF (R = 0.52, P < 0.001). Female subjects had smaller LVIDd than males (LVIDd 52 ± 5 vs. 57 ± 4 mm, P = 0.001), higher EF (58 ± 5% vs. 54 ± 7%, P = 0.009), and better GLS (−21.1 ± 2.8% vs. −19.1 ± 2.5%, P = 0.009).

By CMR, LVEF was 53 ± 6%, and RVEF was 51 ± 3%. There was a trend towards lower LVEF by CMR in patients with %PVC ≥ 8 (P = 0.06). There was a moderate correlation between CMR LVEF and %PVC (R = 0.44, P = 0.04) but no correlation between RVEF and %PVC (R = 0.13, P = 0.56). No subjects had CMR‐criteria for ARVC12 or signs of other heart disease.

Serious arrhythmic events

Eleven patients (21%) had experienced cardiac syncope and/or sustained VT requiring acute medical attention (Table 3). Compared with patients without events, these patients had wider PVC QRS duration (156 ± 19 vs. 142 ± 17 ms, P = 0.03), shorter SR QRS duration (82 ± 9 vs. 92 ± 11 ms, P = 0.006), and thus an increased QRS ratio (1.91 ± 0.30 vs. 1.56 ± 0.20, P < 0.001). QRS ratio was a marker of serious arrhythmic events, independently of age, sex, flecainide use, GLS, and RVLS (Table 3). Using the predefined QRS ratio ≥1.9 as a marker of an RVOT‐free wall PVC origin,13 serious events occurred in 7/9 (78%) patients with RVOT‐free wall PVC origin, while only in 4/41 (10%) of patients with an RVOT septal wall PVC origin (P < 0.001). %PVC and resting heart rate did not differ between patients without and with arrhythmic events (P = 0.71 and P = 0.82, respectively). In univariable analyses, GLS and RVLS were slightly better in patients with serious arrhythmic events; however, in a multivariable analysis, these associations were no longer evident.

Table 3.

Characteristics of 52 patients with outflow tract arrhythmia, without and with serious arrhythmic events.

| No serious events | Serious events | P‐value | Adjusted odds ratio | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 41 | n = 11 | (95% CI) | |||

| Female, n (%) | 21 (51) | 8 (73) | 0.21 | 1.0 (0.1–9.3) | 0.97 |

| Age, years | 47.4 ± 10.8 | 41.5 ± 14.2 | 0.14 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.00 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.97 ± 0.18 | 1.94 ± 0.25 | 0.66 | ||

| NSVT, n (%) | 24 (59) | 6 (55) | 0.82 | ||

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 35 (85) | 8 (73) | 0.36 | ||

| Flecainide, n (%) | 5 (12) | 5 (45) | 0.01 | 13 (1–160) | 0.05 |

| ECG parameters | |||||

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 64 ± 12 | 63 ± 12 | 0.82 | ||

| PVC, % | 8 (0, 60) | 7 (0, 46) | 0.76 | ||

| PVC QRS, ms | 142 ± 17 | 156 ± 19 | 0.03 | ||

| Sinus QRS, ms | 92 ± 11 | 82 ± 9 | 0.006 | ||

| QRS ratio | 1.56 ± 0.22 | 1.91 ± 0.29 | <0.001 | 1.7 (1.0–2.7) | 0.04 |

| Coupling interval, ms | 470 (300, 840) | 430 (350, 580) | 0.74 | ||

| RVOT free wall, n (%) | 2 (5) | 7 (64) | <0.001 | ||

| Imaging | |||||

| LVEF, % | 56 ± 6 | 58 ± 5 | 0.36 | ||

| GLS, % | −19.8 ± 2.8 | −21.7 ± 2.6 | 0.05 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.52 |

| LVIDd, mm | 54 ± 6 | 53 ± 3 | 0.28 | ||

| MD, ms | 44 ± 13 | 38 ± 14 | 0.16 | ||

| TAPSE, mm | 23 ± 4 | 22 ± 4 | 0.75 | ||

| RVD, mm | 39 ± 4 | 37 ± 6 | 0.20 | ||

| RVOT, mm | 34 ± 5 | 32 ± 6 | 0.44 | ||

| RVLS, % | −26.8 ± 4.6 | −30.5 ± 5.8 | 0.03 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.16 |

| CMR LVEF (n = 22), % | 53 ± 6 | 51 ± 5 | 0.65 | ||

| CMR RVEF (n = 22), % | 51 ± 4 | 52 ± 2 | 0.72 | ||

BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal strain; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter in diastole; MD, mechanical dispersion; NSVT, non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia; PVC, premature ventricular contractions; RVD, basal right ventricular diameter; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; RVLS, right ventricular longitudinal strain; RVOT, proximal right ventricular outflow tract in parasternal short axis view; TAPSE, tricuspid annulus plane systolic excursion; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Values are mean ± SD or median (range) unless stated otherwise. P‐values are calculated by unpaired Student's t‐test, χ2, or Mann–Whitney U test. Odds ratio and adjusted P‐values by multivariable logistic regression.

Discussion

This study showed that a %PVC >8 was associated with impaired myocardial function in patients with OTA. This is only one third of the %PVC threshold suggested to impair cardiac function in previous studies,7 indicating that early impairment of myocardial function can be detected by GLS and may warrant PVC‐reducing therapy. Furthermore, serious arrhythmic events were relatively frequent, occurring in about 20% of patients. Serious arrhythmic events were associated with a suggested RVOT‐free wall PVC origin.

Myocardial function

Previous reports have defined %PVC >24 as a critical threshold for PVC‐induced cardiomyopathy.7 Our results indicated that a significantly lower %PVC may impair the myocardial function. An impaired myocardial function by GLS was evident already at %PVC >8, and %PVC was a robust marker of worse GLS independently of sex, age, and body surface area. Furthermore GLS correlated linearly with %PVC, while EF did not. GLS is superior to EF in detecting subtle myocardial dysfunction, in particular when EF is relatively preserved.9, 21 A GLS worse than −18% has been reported to be a sensitive and independent predictor of heart failure.22 It may indicate the onset of adverse cardiac remodelling and be an early sign of heart failure also when EF is preserved.23 We found abnormal myocardial function with reduced GLS and increased mechanical dispersion at a %PVC far below the previously suggested values, indicating that PVC inhibiting therapy may be considered in patients with less frequent PVCs than previously reported. This was further supported by a trend towards higher LVEF by CMR in patients with %PVC >8, although only a subset of patients underwent CMR. Furthermore, previous studies on PVC‐induced cardiomyopathy have defined impaired LV function by EF <45–50%.7, 24, 25, 26, 27 EF <45–50% indicates a clearly impaired systolic function, as novel reference values for EF define 52% (male) and 54% (female) as the lower normal values.15 This may explain the higher %PVC thresholds reported in previous studies compared with our results.

We observed a weak correlation between %PVC and proximal RVOT diameter, although the RVOT diameter did not differ between the patients with high and low %PVC. This study was not designed to evaluate the causal relationship. Future studies should explore whether the RVOT dilates with increasing %PVC or if a dilated RVOT elicits more frequent PVCs in OTA.

Premature ventricular contraction origin and serious arrhythmic events

Although OTA is normally considered a benign condition, as many as one fifth of our OTA patients had experienced sustained VT and/or syncope. This high frequency was likely to have been influenced by the frequent referral of patients with events for evaluation and treatment at our tertiary centre and did probably not represent the true incidence of serious arrhythmic events in this patient group. Nevertheless, it highlights that OTA is not a uniformly benign condition. Patients with serious arrhythmic events had increased PVC QRS duration and shorter sinus QRS duration resulting in an increased QRS duration ratio, which has been associated with a PVC origin in the free wall of the RVOT.13 The QRS ratio was an independent marker of serious arrhythmic events. Our study therefore indicated that OTA patients with PVCs from the RVOT‐free wall may have a more malignant arrhythmic phenotype. Flecainide was more frequent in patients with serious events (n = 5). However, these five patients received flecainide after the serious arrhythmic event, excluding the interpretation of pro‐arrhythmic effects of flecainide. The mechanism behind RVOT‐free wall as a more malignant PVC origin was not explored in this study. Electrophysiological studies are needed to confirm the origin and to further explain our finding. Patients with events had a tendency to better GLS and RVLS than patients without events. However, when adjusted for confounders in multivariable analysis, this difference was no longer evident. Arrhythmic events were recorded retrospectively prior to echocardiography, with inherent uncertainties. These results may however indicate that fibrosis was not the arrhythmogenic aetiology in those with serious arrhythmic events and were supported by the lack of fibrosis on CMR and by measures of preserved GLS and mechanical dispersion. However, because of the limited number of serious events, negative findings should be interpreted with caution.

Clinical implications

Our results indicated that patients with OTA and >8%PVC (app. 8000 PVCs/24 h) should be evaluated by echocardiography to assess cardiac function and be considered for PVC inhibiting treatment. Myocardial function by GLS was reduced at >8%PVC, but although it was a sensitive functional correlate of PVC burden, our study did not investigate the prognostic impact of reduced GLS on long‐term heart failure development. This study was not designed to investigate the treatment effects of inhibiting PVCs, but previous studies have demonstrated improved myocardial function after catheter ablation of the PVC focus.28, 29 Future prospective clinical studies should explore whether discrete myocardial dysfunction is associated with risk of heart failure in OTA patients and whether heart failure treatment should be initiated at an early stage in addition to PVC inhibiting treatment.

A suggested RVOT‐free wall PVC origin was associated with a more malignant clinical phenotype, a finding that should be evaluated in prospective clinical studies and confirmed by electrophysiological studies.

Limitations

The number of patients in the present study was limited. Furthermore, the PVC frequency is dynamic,30 and our %PVC estimate was based on a single 24 h Holter recording. However, this is a reflection of everyday clinical practice. Our definition of abnormal GLS worse than −18% was based on a previous meta‐analysis.16 There is currently no clear consensus on the normal range of GLS, and the optimal range is probably vendor and lab‐specific. A referral bias due to selection of patients with serious arrhythmic events for evaluation and therapy at our tertiary centre may have overestimated the prevalence of serious arrhythmic events among OTA patients. The PVC origin was merely suggested by PVC morphology and QRS ratio and was not confirmed by invasive electrophysiological studies. However, the algorithm suggesting optimal ablation site in OTA has been validated to correlate well with the invasively established origin of PVCs.13 We also recognize that because of a limited number of variables, there was a possibility of overfitting in the multivariable logistical regression analyses.

Conclusions

More than 8%PVC was associated with impaired myocardial function by GLS in patients with OTA, which is a considerably lower threshold of %PVC than previously reported. This finding indicates that patients with more than approximately 8000 PVCs/24 h should undergo strain echocardiography to evaluate cardiac function and to consider PVC inhibiting treatment if appropriate, although the prognostic value remains unclear. OTA is considered a benign condition, but one fifth had serious arrhythmic events. These patients more frequently had an RVOT‐free wall PVC origin.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by a public research grant from the South‐Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, Oslo, Norway, and the Center for Cardiological Innovation funded by the Norwegian Research Council.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all study participants for their valuable contribution.

Lie, Ø. H. , Saberniak, J. , Dejgaard, L. A. , Stokke, M. K. , Hegbom, F. , Anfinsen, O.‐G. , Edvardsen, T. , and Haugaa, K. H. (2017) Lower than expected burden of premature ventricular contractions impairs myocardial function. ESC Heart Failure, 4: 585–594. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12180.

References

- 1. Lerman BB. Mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment of outflow tract tachycardia. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015; 12: 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Viskin S, Antzelevitch C. The cardiologists' worst nightmare sudden death from “benign” ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46: 1295–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Osmonov D, Ozcan KS, Ekmekci A, Gungor B, Alper AT, Gurkan K. Tachycardia‐induced cardiomyopathy due to repetitive monomorphic ventricular ectopy in association with isolated left ventricular non‐compaction. Cardiovasc J Afr 2014; 25: e5–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yao J, Xu J, Yong YH, Cao KJ, Chen SL, Xu D. Evaluation of global and regional left ventricular systolic function in patients with frequent isolated premature ventricular complexes from the right ventricular outflow tract. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012; 125: 214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rita E, Marinelli A, Scipione P, Cecchetti P, Molini S, Misiani A, Pupita G, Capucci A. Cardiomyopathy induced by frequent premature ventricular complexes originating from the right ventricular outflow tract: left ventricular systolic function recovery after transcatheter ablation. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2011; 12: 383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chugh SS, Shen WK, Luria DM, Smith HC. First evidence of premature ventricular complex‐induced cardiomyopathy: a potentially reversible cause of heart failure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2000; 11: 328–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baman TS, Lange DC, Ilg KJ, Gupta SK, Liu TY, Alguire C, Armstrong W, Good E, Chugh A, Jongnarangsin K, Pelosi F Jr, Crawford T, Ebinger M, Oral H, Morady F, Bogun F. Relationship between burden of premature ventricular complexes and left ventricular function. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7: 865–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leren IS, Hasselberg NE, Saberniak J, Haland TF, Kongsgard E, Smiseth OA, Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH. Cardiac mechanical alterations and genotype specific differences in subjects with long QT syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015; 8: 501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haugaa KH, Grenne BL, Eek CH, Ersboll M, Valeur N, Svendsen JH, Florian A, Sjoli B, Brunvand H, Kober L, Voigt JU, Desmet W, Smiseth OA, Edvardsen T. Strain echocardiography improves risk prediction of ventricular arrhythmias after myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 6: 841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH. Imaging assessment of ventricular mechanics. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2011; 97: 1349–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kolias TJ, Edvardsen T. Beyond ejection fraction: adding strain to the armamentarium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9: 922–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MG, Daubert JP, Fontaine G, Gear K, Hauer R, Nava A, Picard MH, Protonotarios N, Saffitz JE, Sanborn DM, Steinberg JS, Tandri H, Thiene G, Towbin JA, Tsatsopoulou A, Wichter T, Zareba W. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation 2010; 121: 1533–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang F, Chen M, Yang B, Ju W, Chen H, Yu J, Lau CP, Cao K, Tse HF. Electrocardiographic algorithm to identify the optimal target ablation site for idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract ventricular premature contraction. Europace 2009; 11: 1214–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pedersen CT, Kay GN, Kalman J, Borggrefe M, Della‐Bella P, Dickfeld T, Dorian P, Huikuri H, Kim YH, Knight B, Marchlinski F, Ross D, Sacher F, Sapp J, Shivkumar K, Soejima K, Tada H, Alexander ME, Triedman JK, Yamada T, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Kuck KH, Mont L, Haines D, Indik J, Dimarco J, Exner D, Iesaka Y, Savelieva I. EHRA/HRS/APHRS expert consensus on ventricular arrhythmias. Europace 2014; 16: 1257–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015; 16: 233–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yingchoncharoen T, Agarwal S, Popovic ZB, Marwick TH. Normal ranges of left ventricular strain: a meta‐analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013; 26: 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saberniak J, Hasselberg NE, Borgquist R, Platonov PG, Sarvari SI, Smith HJ, Ribe M, Holst AG, Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH. Vigorous physical activity impairs myocardial function in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and in mutation positive family members. Eur J Heart Fail 2014; 16: 1337–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mukherjee M, Chung SE, Ton VK, Tedford RJ, Hummers LK, Wigley FM, Abraham TP, Shah AA. Unique abnormalities in right ventricular longitudinal strain in systemic sclerosis patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9: e003792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Motoki H, Borowski AG, Shrestha K, Hu B, Kusunose K, Troughton RW, Tang WH, Klein AL. Right ventricular global longitudinal strain provides prognostic value incremental to left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with heart failure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014; 27: 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saberniak J, Leren IS, Haland TF, Beitnes JO, Hopp E, Borgquist R, Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH. Comparison of patients with early‐phase arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and right ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 18:62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stanton T, Leano R, Marwick TH. Prediction of all‐cause mortality from global longitudinal speckle strain: comparison with ejection fraction and wall motion scoring. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009; 2: 356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang H, Negishi K, Wang Y, Nolan M, Saito M, Marwick TH. Echocardiographic screening for non‐ischaemic stage B heart failure in the community. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 1331–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haugaa KH, Edvardsen T. Global longitudinal strain: the best biomarker for predicting prognosis in heart failure? Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 1340–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yokokawa M, Kim HM, Good E, Crawford T, Chugh A, Pelosi F Jr, Jongnarangsin K, Latchamsetty R, Armstrong W, Alguire C, Oral H, Morady F, Bogun F. Impact of QRS duration of frequent premature ventricular complexes on the development of cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9: 1460–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanei Y, Friedman M, Ogawa N, Hanon S, Lam P, Schweitzer P. Frequent premature ventricular complexes originating from the right ventricular outflow tract are associated with left ventricular dysfunction. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2008; 13: 81–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bogun F, Crawford T, Reich S, Koelling TM, Armstrong W, Good E, Jongnarangsin K, Marine JE, Chugh A, Pelosi F, Oral H, Morady F. Radiofrequency ablation of frequent, idiopathic premature ventricular complexes: comparison with a control group without intervention. Heart Rhythm 2007; 4: 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yarlagadda RK, Iwai S, Stein KM, Markowitz SM, Shah BK, Cheung JW, Tan V, Lerman BB, Mittal S. Reversal of cardiomyopathy in patients with repetitive monomorphic ventricular ectopy originating from the right ventricular outflow tract. Circulation 2005; 112: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wijnmaalen AP, Delgado V, Schalij MJ, van Huls van Taxis CF, Holman ER, Bax JJ, Zeppenfeld K. Beneficial effects of catheter ablation on left ventricular and right ventricular function in patients with frequent premature ventricular contractions and preserved ejection fraction. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2010; 96: 1275–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takemoto M, Yoshimura H, Ohba Y, Matsumoto Y, Yamamoto U, Mohri M, Yamamoto H, Origuchi H. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of premature ventricular complexes from right ventricular outflow tract improves left ventricular dilation and clinical status in patients without structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45: 1259–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loring Z, Hanna P, Pellegrini CN. Longer ambulatory ECG monitoring increases identification of clinically significant ectopy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol: PACE 2016; 39: 592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]