SUMMARY

Greater understanding of the complex host responses induced by type 1 Interferon (IFNs) cytokines could allow new therapeutic approaches for diseases in which these cytokines are implicated. We found that in response to the Toll-like receptor-9 agonist CpGA, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) produced type 1 IFNs which, through an autocrine type 1 IFN receptor-dependent pathway, induced changes in cellular metabolism characterized by increased fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Direct inhibition of FAO, and of pathways that support this process, such as fatty acid synthesis, prevented full pDC activation. Type 1 IFNs also induced increased FAO and OXPHOS in non-hematopoietic cells and were found to be responsible for increased FAO and OXPHOS in virus-infected cells. Increased FAO and OXPHOS in response to type 1 IFNs was regulated by PPARα. Our findings reveal FAO, OXPHOS and PPARα as potential targets to therapeutically modulate downstream effects of type 1 IFNs.

eTOC blurb

Type 1 IFN cytokines play complex and incompletely understood roles in immunity. Pearce and colleagues have shown that these cytokines upregulate fatty acid oxidation, and that this metabolic change plays a critical role in plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation and in anti-viral effects induced by type 1 IFNs.

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic changes in mammalian cells are known to occur in response to changes in nutrients and/or oxygen availability and to growth factors. However, recent evidence indicates that, in innate immune cells, signaling downstream of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokine receptors is able to affect metabolism, and that this plays a role in determining cellular function and fate (O’Neill and Pearce, 2016). For example, in conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), Toll like receptor (TLR) agonists induce a rapid (within minutes) increase in glycolysis that results in increased flux of glucose carbon into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Everts et al., 2014). This is required to meet demands for fatty acid synthesis, which is critical for DC activation (Everts et al., 2014; Pearce and Everts, 2015).

Amongst DCs, plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) represent a lineage that is distinct from cDCs, and specialized for type 1 interferon (IFN) production (Swiecki and Colonna, 2015) in response to TLR7 or TLR9 agonists (Ito et al., 2005). In response to stimulation though these PRRs, pDCs can also produce IL-6, TNF-α and IL-12, and increase their antigen presenting abilities. The type 1 IFNs IFN-α and IFN-β bind to the IFN-α receptor, IFNAR, which is broadly expressed on many cell types (Ivashkiv and Donlin, 2014). Signaling through IFNAR induces the expression of hundreds of Interferon Response Genes (ISGs) (Schneider et al., 2014), which amongst other functions elicit anti-viral programs, and modulate immunity through effects on antigen presenting cells and T cells (Swiecki and Colonna, 2015). Recent reports have indicated that type 1 IFNs affect cellular lipid metabolism by inhibiting de novo cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis and upregulating uptake of exogenous lipids (Blanc et al., 2011; York et al., 2015) and that this is critical for resistance to viral challenge.

We speculated that the distinct ontogeny and function of pDCs compared to cDCs could mean that they differ metabolically. We observed a significant increase in OXPHOS supported by FAO in pDCs stimulated with the TLR9 agonist CpGA that developed with a kinetic that indicated that late changes in gene expression were critical. Deeper analysis revealed that this process was initiated following type 1 IFN production and autocrine (or paracrine) signaling through IFNAR. Our data indicate that changes in fatty acid metabolism are integral to, and critical for, changes in target cell function induced by type 1 IFNs, and raise the possibility of manipulating metabolic pathways to regulate beneficial and detrimental type 1 IFN-related immune effects.

RESULTS

pDCs stimulated through TLR9 have increased FAO and OXPHOS that are critical for activation

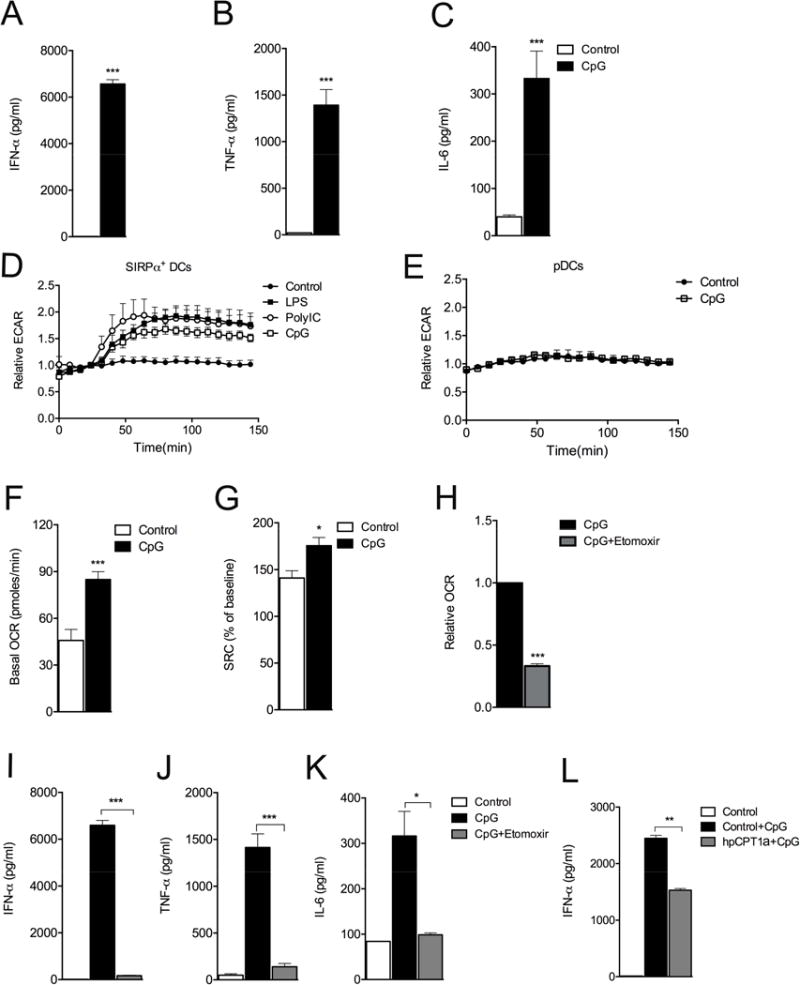

DC activation in response to TLR agonists is accompanied by coordinated increases in glucose utilization and the expression of genes encoding cytokines, chemokines and surface proteins that collectively allow DCs to promote inflammation and present antigens to T cells to initiate adaptive immunity (Joffre et al., 2009). The increase in glycolytic rate in TLR-agonist stimulated DCs is essential for DC activation and occurs in all types of cDCs examined (Everts et al., 2012; Krawczyk et al., 2010). We asked whether similar changes in metabolism are critical for pDC activation. When we stimulated pDCs sorted from FLT3-L bone marrow cultures (Fig. S1A) (Naik et al., 2007) with CpGA for 24 h, we were able to measure secreted IFN-α (Fig. 1A), TNF-α (Fig. 1B) and IL-6 (Fig. 1C) in cell supernatants, and increased surface expression of CD86 (Fig. S1B). We asked whether activation of pDCs in response to CpGA was accompanied by metabolic changes. SIRPα+ cDCs sorted from FLT3-L cultures, like other cDCs, responded to a range of TLR agonists, including CpGA, with a rapid increase in aerobic glycolysis (measured by extracellular flux analysis, EFA, as increased extracellular acidification rate, ECAR, an indication of the secretion of lactate, an end product of aerobic glycolysis) (Fig. 1D). However, pDC activation in response to CpGA was not accompanied by a rapid change in ECAR (Fig. 1E). Nevertheless, using EFA we measured increases in basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and spare respiratory capacity (SRC) (Brand and Nicholls, 2011; Ferrick et al., 2008), in pDCs that had been activated with CpGA for 24 h compared to in resting pDCs (Fig. 1F,G, S1C). The control dinucleotide CpGB had no effect on metabolism (Fig. S1D), and compared to CpGA, the TLR7 agonist.imiquimod induced the expression of lower amounts of IFN-α and larger amounts of IL-6 and TNF-α, but also increased basal OCR (Fig. S1E).

Figure 1. Stimulation of pDCs by CpGA results in an increase in FAO that is essential for cellular activation.

CD11cintB220+Siglec H+ pDCs were sorted from Flt3L-bone marrow cultures at day 8, and stimulated with TLR agonists. (A) IFN-α was measured by ELISA at 24h post activation. (B) IL-6 and (C) TNF-α were measured in the same samples using CBA. (D,E) ECAR of SIRPα+DCs (D) and pDCs (E), following treatment with TLR agonists, were determined by EFA. (F) Basal OCR, and (G) SRC were determined by EFA. (H,I,J,K) Relative basal OCR (I), or cytokine production (I–K) of pDCs activated with CpGA without or with etomoxir. (L) IFNα production by pDCs transduced with retrovirus encoding either shRNA against luciferase (control) or CPT1a (hpCPT1a) and stimulated without or with CpGA. In D and E, data are mean ± SEM of reads from triplicate samples from one experiment, and are representative of data from 3 experiments. In the other panels, data are mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments. All differences are statistically significant (at least P< 0.05, Student’s t-test); *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Please see Figure S1.

Given the marked differences in ECAR in CpGA stimulated cDCs and pDCs, we additionally examined CpGA-induced changes in OXPHOS in cDCs. While CpGA did induce increases in OCR in these cells, these were lower than in pDCs, and cDCs had comparatively little SRC (Fig. S1F). We found that the TLR3 agonist, PolyI:C, which also promotes Type 1 IFN production, had no effect on pDC OCR (Fig. S1G), but had an equivalent effect to CpGA on cDC OCR (Fig. S1H), consistent with the fact that TLR3 is expressed by cDCs and not pDCs (Wang et al., 2011).

In other immune cells, increased basal OCR and SRC are indicators of enhanced FAO (Huang et al., 2014; van der Windt et al., 2012). To explore whether increased OCR and SRC reflect increased FAO in CpGA-activated pDCs, we targeted Cpt1a, which is responsible for the entry of activated fatty acids (FA) into mitochondria for FAO. First, we stimulated pDCs with CpGA in the presence or absence of the Cpt1a inhibitor etomoxir. Etomoxir inhibited the TLR agonist-induced increase in basal OCR (Fig. 1H) and collapsed the SRC in pDCs stimulated with CpGA for 24h (Fig. S1D), indicating that stimulation of pDCs by CpGA results in enhanced OXPHOS largely due to increased FAO. Consistent with this, we found that mitochondrial membrane potential was significantly increased by stimulation with CpGA, and that this effect was partially blocked by etomoxir (Fig. S1I). We next asked whether the observed metabolic changes were necessary for cellular activation. We found that pDCs cultured with CpGA plus etomoxir produced significantly less IFN-α, TNF-α, and IL-6 than cells stimulated with CpGA alone (Fig. 1I,J,K). Increased expression of CD86 following stimulation with CpGA was also inhibited by etomoxir (Fig. S1B). Etomoxir had no effect on viability (Fig. S1J). Moreover, we found that CpGA-induced pDC activation, measured by IFN-α production, was significantly impaired when Cpt1a expression was suppressed genetically using a shRNA, (Fig. 1L). Imiquimod-stimulated IFN-α production was also diminished by etomoxir (Fig. S1K), although not to the same extent as in cells stimulated with CpGA.

Together, our data show that TLR9-mediated pDC activation is accompanied by increased OXPHOS due to FAO, and that this metabolic change is essential for activation.

CpGA simulates type 1 IFN production and changes in expression of genes encoding metabolic pathways

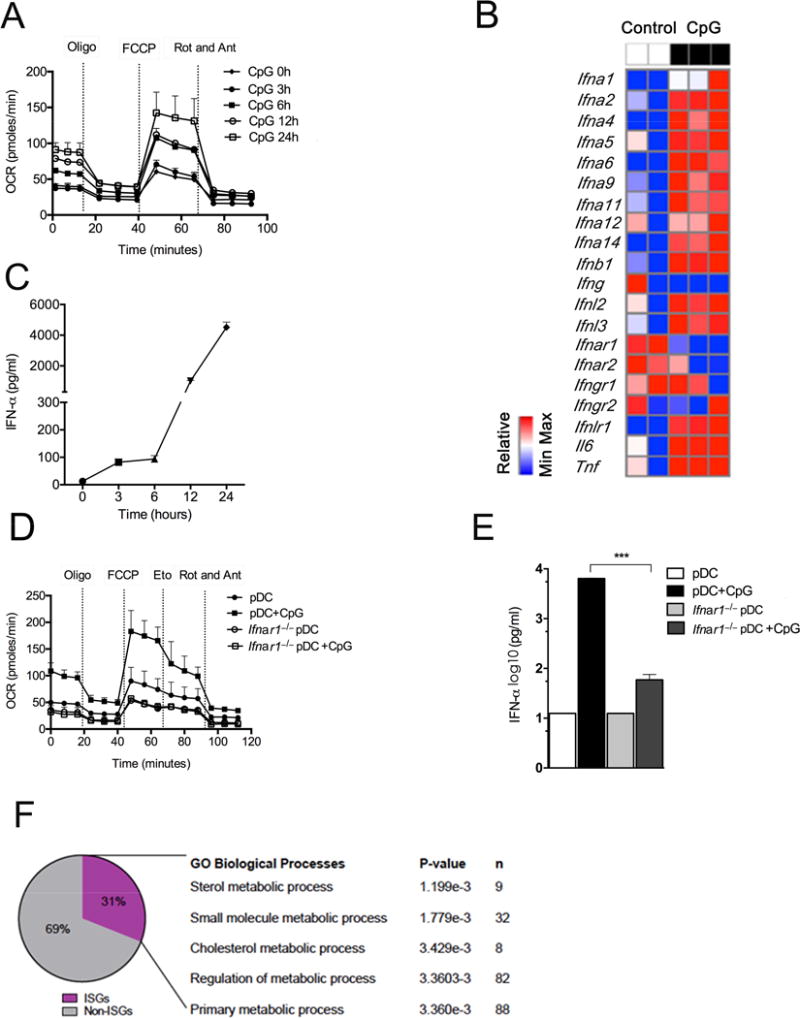

Observed changes in OXPHOS at 24h post stimulation prompted us to look at earlier time points to determine when metabolic reprogramming occurred. Unlike changes in ECAR in cDCs following stimulation with TLR agonists, changes in OCR were not apparent at early times after pDCs were treated with CpGA (Fig. S2A). This suggested that metabolic change was the result of new gene expression rather than early posttranscriptional changes associated with TLR9 ligation. We found that increased OCR was first evident at 6 h post stimulation, and became increasingly apparent thereafter (Fig. 2A). This pattern was consistent with feedback stimulation by the product of a gene that was expressed directly in response to CpGA, a candidate for which is type 1 IFN. Typically, type 1 IFNs are made in response to an initial stimulus and then are further induced in response to binding of type 1 IFN to IFNAR, a receptor that is expressed on pDCs and most other cell types (Ivashkiv and Donlin, 2014). Type 1 IFNs have been implicated in DC activation previously (Asselin-Paturel et al., 2005; Dai et al., 2011; Faul et al., 2010). We examined type 1 IFN production following CpGA-stimulation and found that mRNAs coding Type 1 IFNs were increased in CpGA-stimulated cells (Fig. 2B). We found that IFN-α protein was produced in two phases, the first between 0 and 6h, during which relatively small amounts of cytokine were made, and then during a second phase between 12h and 24h, which accounted for the majority of IFN-α produced (Fig. 2C), consistent with auto-induction of this cytokine. A two phase kinetic was also apparent for TNF-α and IL-6 production (Figs. S2B,C). To directly ask whether type 1 IFN signaling is critical for increased FAO in response to CpGA, we stimulated Ifnar1−/− pDCs with CpGA and measured OCR. We found that the increase in FAO characteristic of CpGA-stimulated WT pDCs failed to occur in the absence of IFNAR (Fig. 2D). IFNAR deficiency, like etomoxir-treatment (Fig. 1), inhibited IFN-α production in response to CpGA (Fig. 2E), and diminished IFN-α production in response to imiquimod (Fig. S2D). We found that inhibitory effects of etomoxir on OCR and SRC were similar in unstimulated pDCs and in pDCs that had been stimulated with CpGA for 3h, but more marked in stimulated cells by 6h, when OCR and SRC were enhanced (Fig. 2A) presumably due to the initiation of type 1 IFN signaling (Fig. S2E). Thus IFN-α production and IFNAR signaling are interlinked with changes in metabolism and activation following CpGA-stimulation in pDCs. Analysis of changes in gene expression induced by CpGA revealed a distinct ISG signature in which, of the genes that were differentially expressed (vs. unstimulated cells) at 24h post CpGA stimulation, approximately one third were ISGs, indicating that the cells had responded to type 1 IFN despite having been stimulated only with CpGA. Of these ISGs, over 25% were involved in metabolic processes (Fig. 2F). Thus CpGA stimulates type 1 IFN production and autocrine signaling that leads to extensive changes in the expression of metabolism genes.

Figure 2. Stimulation of pDCs with CpGA results in type 1 IFN production that plays an essential role in subsequent changes in cellular metabolism and activation.

(A)Mitochondrial fitness tests were used to compare OCR of pDCs stimulated with CpGA for times indicated. Data represent mean ± SEM of reads from triplicate samples from one experiment, and are representative of data from 3 experiments. (B) RNAseq analysis of Type 1 IFNs, Il6 and Tnf expression induced in pDCs by CpGA stimulation for 24h. Data from 2 separate control and 3 separate CpGA-stimulated cell samples are shown. (C) IFN-α accumulation in pDC culture supernatant at times indicated post activation with CpGA. Data are mean ± SEM from 3 independent samples from one experiment, and are representative of data from 4 experiments. (D) Mitochondrial fitness tests were used to compare OCR of resting or CpGA-stimulated WT or Ifnar1−/− pDCs. Data are mean ± SEM of reads from triplicate samples from one experiment, and are representative of data from 3 experiments. (E) IFN-α production by resting or CpGA-stimulated WT or Ifnar1−/− pDCs. Bars represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (F) Genes expressed differentially in CpGA-activated vs. resting pDCs were identified by analysis of RNAseq data. This dataset was analyzed using INTERFEROME. The subset of ISGs was analyzed for GO biological processes using DAVID. All differences shown are statistically significant (at least P < 0.05, Student’s t-test); *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Please see Figure S2.

Type 1 IFN alone is sufficient to induce increased FAO and OXPHOS

The finding that changes in OXPHOS in CpGA-stimulated pDCs result from signaling through IFNAR raised the possibility that stimulation with type 1 IFNs alone may be able to promote FAO. We stimulated pDCs with IFNα and measured OCR in a mitochondrial stress test 24h later. In this assay, FAO, evident as increased basal OCR, SRC, and sensitivity of SRC to etomoxir, was increased in response to IFN-α, and this response was IFNAR-dependent (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the fact that IFNAR is also the receptor for IFN-β, this type 1 IFN was also able to stimulate an increase in FAO in pDCs (Fig S3A). Additionally, we found that IFN-α was as capable as CpG at stimulating increases in OCR in cDCs (Fig. S3B compared with Fig. S1F).

Figure 3. IFN-α directly promotes FA oxidation.

(A) Mitochondrial fitness tests were used to compare OCR of WT and Ifnar1−/− pDCs stimulated with IFN-α, as indicated. (B) OCR values during a mitochondrial fitness test, (C) basal OCR, and (D) maximal OCR of PDV epithelial cells that had been cultured without (control) or with IFN-α for 24 h. (E) OCR values during a mitochondrial fitness test, and (F) basal OCR comparison, of PDV epithelial cells that had been cultured without (control) or with IFN-α or IFN-α plus anti-IFNAR (MAR1-5A3) for 24 h. Data are mean ± SEM of reads from triplicate samples from one experiment representative of 3 (A,B,E), or mean values ± SEM from 3 or more independent experiments (C,D,F). All differences shown are statistically significant (at least P < 0.05, Student’s t-test); *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Please see Figure S3.

IFNAR is expressed broadly, so other cell types may be receptive to type 1 IFN-driven-alterations in metabolism. To test this we asked whether type 1 IFN could promote OXPHOS in epithelial cells (PDV keratinocytes). We found that basal (Fig. 3B,C) and maximal OCR (Fig. 3B,D) were increased by stimulation with IFN-α, although these cells had measurable SRC at rest that was not increased following stimulation with IFN-α (Fig. 3B). A blocking antibody against IFNAR (MAR1-5A3) prevented changes in OCR following the addition of IFNα (Fig. 3E,F). We also examined type 1 IFN induced changes in CD8+ T cell metabolism. In these cells, IL-15 stimulates differentiation into memory cells that is coupled to, and dependent upon, enhanced OXPHOS due to FAO and evident as increased SRC (van der Windt et al., 2012). We examined the effects of IFN-α on OXPHOS in CD8+ T cells that had been activated with IL-2 alone (which generates short-lived effector, TEFF, cells), or IL-2 plus IL-15 (which generates memory, TMEM cells) (Fig. S3C). As expected, TMEM cells but not TEFF cells had SRC (Figs. S3D,E respectively). IFN-α increased SRC, although not basal OCR, in the TMEM cells but had no measurable effect on TEFF cells (Figs. S3D,E respectively). Together, these data indicate that type 1 IFNs are capable of enhancing oxidative metabolism in disparate hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells.

Type 1 IFN induced changes in metabolism, type 1 IFN production and viral infection are interlinked

Type 1 IFN production is stimulated by viral infection. We reasoned that, due to autocrine signaling through IFNAR, virus infected cells would exhibit similar metabolic changes to cells stimulated directly with IFN-α. We found that basal and maximal OCR were markedly increased by infection of PDV cells with LCMV Arm for 24h (Figs. 4A,B), and that increased basal OCR due to viral infection was prevented by MAR1-5A3 (Fig. 4B, and data not shown) and by etomoxir (Fig. S4A). Moreover, SRC in virus-infected cells was sensitive to etomoxir (Fig. S4B). To test whether FAO is generally important for type-1 IFN production in vivo, we treated mice with etomoxir, and then infected them and untreated controls with LCMV. We found that plasma IFN-α at day 3 post infection was significantly reduced in infected mice as a result of etomoxir treatment (Fig. 4C). Etomoxir-treated and infected mice also had substantially fewer splenic pDCs than untreated infected controls (which themselves exhibited a decrease in pDCs compared to uninfected controls, as reported previously (Swiecki et al., 2011)) (Fig. S4C), and significantly more LCMV was detected in liver and spleen of etomoxir treated vs. untreated infected mice (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that the induction of FAO and OXPHOS by type 1 IFN, and optimal type 1 IFN production and viral control following infection, are interlinked.

Figure 4. Viral infection induces type 1 IFN-dependent changes in host cell FAO that are important for further type 1 IFN production and anti-viral effects.

(A) OCR values during a mitochondrial fitness test of uninfected PDV epithelial cells versus PDV cells infected LCMV Arm for 24 h. (B) Basal OCR of PDV cells at 24 h post infection in the absence or presence of blocking anti-IFNAR Ab. (C,D) C57BL/6J mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV Arm and treated with etomoxir (20 mg/kg) 1 day prior to infection and 1 day afterwards. Serum and tissue were collected at 72 h post-infection and (C) serum IFN-α, and (D) expression of LCMV glycoprotein (LCMV gp) in liver and spleen were measured. Data are mean ± SEM of reads from triplicate samples from one experiment representative of 3 (A), or mean ± SEM of reads from 3 independent experiments (B-E). All differences shown are statistically significant (at least P < 0.05, Student’s t-test); *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Please see Figure S4.

Increased FAO and OXPHOS in type 1 IFN-activated pDCs are dependent on mitochondrial import of pyruvate and FA synthesis

We attempted to identify mechanisms underlying type 1 IFN induced changes in oxidative metabolism. In recent work it became clear that immune cells can utilize distinct sources of FA to support FAO. For example, CD8+ TMEM cells utilize glucose to synthesize their own FA for FAO (O’Sullivan et al., 2014), whereas M2 macrophages appear to rely more on fats taken up from the environment for FAO (Huang et al., 2014). While CpGA-activated pDCs did not exhibit the rapid changes in glycolytic metabolism that typify TLR-stimulated cDCs, basal ECAR was significantly increased in activated pDCs at 24h post stimulation (Fig. 5A). We asked whether this, as in CD8+ TMEM cells, could be linked to changes in OXPHOS. For this we inhibited the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) using UK5099, which blocks entry of glucose carbon into the TCA cycle (Halestrap, 1975). This had an inhibitory effect on the CpGA-induced production of IFN-α,TNF-α (Figs. 5B,C), IL-6 (data not shown) and expression of CD86 (Fig. S5A). Through the TCA cycle glucose carbon is converted into citrate, which can continue through the TCA cycle to support OXPHOS or be exported into the cytoplasm for FA synthesis (FAS). To explore whether the latter pathway is contributing to FAO in pDCs, we examined the effect of TOFA, an inhibitor of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, a key enzyme in FAS, on CpGA induced activation, and found that it significantly inhibited IFN-α, TNF-α and IL-6 production (Figs. 5D,E, and data not shown), and CD86 expression (Fig. S5A). The FA synthase inhibitor C75 had an equivalent effect on cytokine production by CpGA-activated pDCs (Fig. S5B). Thus CpGA-induced pDC activation is dependent on the import of pyruvate into mitochondria, and on FAS, suggesting that de-novo synthesized FA are important for FAO and OXPHOS in activated pDCs. In support of this, UK5099 and TOFA both significantly diminished basal OCR in CpGA-activated pDCs (Fig. 5F). These inhibitors had no effect on viability (Fig. S5D).

Figure 5. pDC activation is associated with a late increase in glycolysis and requires mitochondrial pyruvate import, and FAS.

Purified pDCs were stimulated with CpGA plus or minus inhibitors for 24 h. (A) Relative change in basal ECAR at 24h post activation with CpGA. (B,C) Effect of the MPC inhibitor UK5099 on IFN-α and TNF-α production by CpGA-stimulated pDCs. (D,E) Effect of the ACC1 inhibitor TOFA on IFN-α and TNF-α production by CpGA-stimulated pDCs. (F) Relative basal OCR of pDCs activated with CpGA without or with inhibitors. (G) Relative basal ECAR of resting pDCs or pDCs stimulated with IFNα for 24 h. (H,I). Relative basal OCR of pDCs (H) or PDV cells (I) stimulated with IFN-α in the absence or presence of inhibitors. For all panels, data are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. All differences shown are statistically significant (at least P < 0.05, Student’s t-test); *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Please see Figure S5.

The regulation of FAO and OXPHOS in pDCs by CpGA was largely the result of autocrine type 1 IFN signaling, and as shown above, IFN-α was able to directly regulate metabolism in pDCs and epithelial cells. Consistent with this, we found that pDCs stimulated with IFN-α for 24 h had increased ECAR (Fig. 5G). Moreover, inhibiting mitochondrial pyruvate import or FAS inhibited increased OCR due to stimulation with IFN-α (Fig. 5H). Increased basal OCR due to stimulation with IFN-α in PDV cells, was also significantly inhibited by TOFA and UK5099 (Fig. 5I).

One possibility to explain the convergent effects of inhibiting pyruvate entry into mitochondria, FAS and FAO is that the inhibitors used to interrogate these pathways affect IFNAR expression and thereby inhibit type 1 IFN signaling. We found that neither UK5099 nor TOFA had any direct effect on IFNAR expression, although etomoxir did diminish IFNAR expression in unstimulated pDCs (Fig. S5C). As expected from our expression analysis (Fig. 2B), CpG stimulation resulted in reduced surface expression of IFNAR (Fig. S5C). However, this reduction in expression associated with stimulation (which was significantly greater than that caused by etomoxir alone), was unaffected by UK5099, TOFA or etomoxir (Fig. S5C).

On balance, our data indicate that cellular activation coupled to the metabolic regulation of FAO and OXPHOS by type 1 IFNs is dependent on the mitochondrial import of pyruvate and the synthesis of FA to support FAO.

Metabolic reprogramming induced by type 1 IFN leads to enhanced ATP availability

We reasoned that type 1 IFN dependent increases in FAO would lead to increased ATP and therefore that the dependence of FAO on pyruvate import into mitochondria and on FAS would mean that inhibition of any of these steps in the pathway would negatively affect the energy balance of activated pDCs. To test this we measured ATP in pDCs before and after activation with CpG, and found that activated cells had significantly increased amounts of ATP (Fig. 6A). This increase was prevented by IFNAR blockade, and stimulation with IFN-α alone led to increases in ATP that were equivalent to those seen in CpGA stimulated cells (Fig. 6A). Moreover, inhibition of FAO, pyruvate import into mitochondria, or FAS all resulted in significant reductions in ATP (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that type 1 IFN-dependent metabolic reprograming in pDCs is associated with increased availability of cellular ATP.

Figure 6. Metabolic reprogramming induced by type 1 IFN leads to enhanced ATP availability.

ATP was measured in pDCs that had been stimulated under various conditions for 24 h: (A) Resting pDCs, or pDCs stimulated with CpGA alone or in the presence of MAR1-5A3 to block IFNAR, or with IFN-α, or (B) pDCs cultured alone or with the indicated inhibitors, or with CpG alone or with the indicated inhibitors. Data are mean ± SEM of reads from triplicate samples from one experiment, representative of 3. The statistical significance of differences in ATP, by Student’s t-test, are marked as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

The metabolic changes in FAO and OXPHOS induced by type 1 IFN are in part PPARα-dependent

We used an unbiased RNA-seq based approach to identify pathways involved in changes in metabolism induced by type 1 IFNs in pDCs. We defined genes that had fold changes of expression >2, and within this set selected all genes related to metabolic pathways as defined by the RGD database (http://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/search/genes.html) (Shimoyama et al., 2015). OXPHOS was the most significant GO term represented within this dataset (Fig. 7A). We performed KEGG pathway enrichment analysis and STRING, a database of known and predicted protein interactions, to analyze the gene set (Jensen et al., 2009). This analysis again showed OXPHOS as a major network induced by IFN-α, and connected FAO to this network (Fig. 7B). These data are consistent with, and support our findings from EFA, inhibitor and genetic loss of function analyses. However, STRING and additional KEGG analysis also revealed a PPARα signature in the data (Fig. 7A,B). We confirmed that PPARα is expressed in pDCs using immunoblot in bone marrow-derived pDCs (Fig. 7C) and flow cytometry in splenic pDCs (Fig. 7D). We found that expression of PPARα in pDCs was not increased by stimulation with CpG (Fig. 7C), although we did detect an approximately 2 fold increase in PPARα mRNA in IFN-α stimulated PDV cells (data not shown). We found only a weak signal for PPARα in cDCs (Fig. 7C). We examined whether PPARα could be playing a role in pDC activation downstream of stimulation with CpGA. We found that the PPARα antagonist GW6471 had an inhibitory effect on CpGA-induced IFN-α production (Fig. 7E) and increases in basal OCR in pDCs (Fig 7F). Moreover, GW6471 inhibited the increases in OCR induced in PDV cells by type 1 IFN (Fig. 7G) and LCMV infection (Fig. 7H,I), and in these cells this was accompanied by a decline in IFN-α-induced protection against viral replication (Fig. 7J).

Figure 7. PPARα responsive gene signature is present in response to stimulation with type I IFN and plays a central role in regulating changes in FA metabolism induced by this cytokine.

Data from RNAseq analysis of resting pDCs vs. pDCs stimulated with IFN-α for 24 h were analyzed. (A) Differentially expressed genes (> 2-fold change) were analyzed to identify metabolic genes defined by RGD genes database (http://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/search/genes.html), which were then examined further using DAVID focused on KEGG pathways. Pathways are color coded to match data in A. This set of differentially expressed metabolic genes was used to develop an interactive network of genes using STRING, that was annotated and modified using Cytoscape. Thicker edges represent interactions with higher support form published literature. KEGG pathways are color-highlighted as in A. Each circle represents an individual gene. Genes with more than one color are components of more than one pathway. (B) Based on the KEGG analysis in A, we specifically expanded the gene search for PPAR signaling pathways and built a network using the same strategy described in A. Individual gene names are shown. (B) Extracts of pDCs, treated as indicated, cDCs, or heart tissue, were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a membrane and probed for PPARα and GAPDH (loading control). (D) Splenic pDCs were fixed and permeabilized, stained with an anti- PPARα antibody, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (E,F) pDCs were stimulated with CpG with or without the PPARα antagonist GW6471 for 24h, after which (E) IFN-α and (F) basal OCR were measured. (G) pDCs were stimulated with IFNα with or without GW6471 for 24h, after which OCR was measured. (H) OCR during a mitochondrial fitness test of PDV cells infected with LCMV Arm in the presence or absence of GW6471 for 24h. (I) Basal OCR of PDV cells infected with LCMV Arm in the presence or absence of GW6471 for 24h. (I) PDV cells were infected with LCMV for 24h in the presence or absence of IFN-α and/or GW6471, after which LCMV gp expression was measured by real time RT-PCR. The data in A and B are from RNAseq analysis of three samples of stimulated and three samples of unstimulated pDCs. Data in C and D are from individual experiments representative of 2 experiments. Data in H are mean ± SEM of reads from triplicate samples from one experiment representative of 3. Data in E-G, I, J are mean values ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. All differences shown are statistically significant (at least P < 0.05, Student’s t-test); *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Please see Figure S6.

We also asked whether PPARα agonism influences metabolism in pDCs or PDV cells. The PPARα agonist gemfibrozil increased basal OCR and SRC in both cell types (Fig.S6A,B). We tested the combined PPARα and PPARγ agonist muraglitazar, and found that it mirrored the effects of gemfibrozil (Fig S6A), suggesting that PPARα has the dominant effect in promoting OXPHOS in pDCs. Gemfibrozil had no effect on basal OCR in cDCs (Fig. S6C).

The requirement for FAS in the type 1 IFN-induced increase in FAO and OXPHOS (Fig. 5) raised the possibility that this pathway could be important for generating lipid ligands to activate PPARα rather than to fuel FAO. We examined this by measuring the effect of inhibiting FAS on the CpGA induced expression of PPARα target genes Acadl and Pltp in pDCs, but found TOFA had no measurable effect on the expression of either of these (Fig. S6D).

These data indicate that PPARα plays a role in promoting FAO and OXPHOS in response to stimulation by type 1 IFNs.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that activation of pDCs by CpGA leads to changes in core metabolism involving increased FAO and OXPHOS. TLR9 ligation induces type 1 IFNs which autocrine signal to drive a metabolic change in lipid metabolism that, in part, depends on the nuclear receptor PPARα. In pDCs the metabolic changes induced by this pathway led to increases in ATP and are critical for full cellular activation. We found that increased FAO and ATP downstream of type 1 IFN initiated signaling requires pyruvate transport into mitochondria and FAS, and our data suggest that FA synthesized de novo are required to fuel FAO in pDCs. Our findings indicate that type 1 IFNs also promote FAO and OXPHOS in non-hematopoietic cells and that FAO is induced by viral infection in an IFNAR-dependent fashion. Our studies suggest that FAO is critical for innate resistance to virus infection in vivo. Together, our data indicate that type 1 IFNs promote FAO and OXPHOS and that this change in metabolism is integral to the functions of these cytokines.

Prior reports showed that type 1 IFNs increase mitochondrial ROS and membrane potential (Yim et al., 2012), both of which are consistent with accentuated FAO and OXPHOS. Our findings illuminate the mechanism through which the commitment to FAO in pDCs occurs via PPARα-mediated changes in metabolism induced by type 1 IFNs. PPARs, in complex with retinoic acid receptors and FA ligands bind to response elements in the promoters of target genes and regulate gene expression (Evans and Mangelsdorf, 2014; Varga et al., 2011). PPARγ has been implicated in DC and macrophage biology (Varga et al., 2011), but our data point to PPARα regulating changes in metabolism in pDCs via IFNAR. PPARα is expressed constitutively in liver and muscle where it controls the expression of genes involved in FAO (Desvergne et al., 2006).

In cDCs TLR signaling is accompanied by a rapid increase in glycolysis which supports FAS to expand endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi for producing and secreting effector molecules (Everts et al., 2014). Since pDCs also become highly secretory upon activation (Swiecki and Colonna, 2015), we assumed they would also require an early burst of glycolysis. However, this was not the case following CpGA stimulation in pDCs. This may reflect the fact that even at rest, pDCs have well developed ER (Siegal et al., 1999), and are primed for high-output protein secretion. Alternatively, pDCs may not need to commit resources for secretion until late following activation, when they start producing cytokines after synthesis of type 1 IFNs and signaling via IFNAR. Our data support the view that newly synthesized FA directly fuel FAO in pDCs, rather than acting as ligands to activate PPARα-containing receptors that regulate FAO (Evans and Mangelsdorf, 2014). Our results imply that FAS occurs after type 1 IFN-stimulation in pDCs. These findings diverge from those shown for macrophages that were stimulated with type1 IFNs for 48h, in which long chain FAS was inhibited (York et al., 2015). A directed analysis of lipid synthesis in our system will be required to definitively address these disparities, but it is plausible that: 1) IFN effects differ between cell types; 2) type 1 IFNs induce a biphasic response in which during the first 24h FAS is increased, and thereafter, e.g at 48h, this pathway is diminished, or 3) flux through the FAS pathway is diminished but remains critical.

The activation of mouse splenic cDCs by polyI:C was reported to require an autocrine type 1 IFN-induced increase in glycolysis and decrease in OXPHOS (Pantel et al., 2014). While not a focus of our work, we did examine PolyI:C-stimulated bone marrow derived cDCs and found them to have increased rather than decreased OCR. These divergent findings may reflect differences in the composition of culture-derived and splenic cDC populations, both of which are heterogeneous. It is also intriguing that the early glycolytic response to CpGA is so different in pDCs and cDCs. We reported that TBK1 plays a role in the induction of glycolysis by TLR4 in DCs grown from bone marrow in GM-CSF (Everts et al., 2014). We speculate that, as in macrophages (Clark et al., 2011), signaling downstream of TLR9 engages TBK1 in cDCs but not pDCs and that this underlies the difference in the early metabolic response between these cell types.

Inhibition of FAO in vivo resulted in a diminished capacity to control viral infection suggesting that induced FAO could serve an anti-viral role. Previous reports indicated that intracellular pathogens manipulate host cell lipid metabolism to meet their own needs and a systems-based approach identified increased glucose carbon flux through the TCA cycle into FAS in cells infected with HCMV (Munger et al., 2008). This study showed that inhibition of FAS prevented HCMV and influenza A replication and thereby identified enzymes in the FAS pathway as targets for the development of anti-virals. In another study, AMP activated kinase (AMPK) was shown to inhibit Rift Valley Fever virus replication by inhibiting ACC1, the enzyme that catalyzes the first step in FAS (Moser et al., 2012); AMPK is a well-documented inducer of FAO (O’Neill and Pearce, 2016). We speculate that FAO induction by type 1 IFNs diverts FA away from anabolic towards catabolic processes, resulting in the oxidation of FA that could otherwise be used for viral replication. However, a counterpoint is that FAS and FAO are needed for producing ATP to support vaccinia virion assembly (Greseth and Traktman, 2014), and ATP from FAO is important for Dengue virus replication (Heaton and Randall, 2010). We speculate that increases in ATP and mitochondrial fitness in type 1 IFN-stimulated pDCs support the energetic demands of activation that include the requirement to produce and export cytokines, and in non-hematopoietic cells to support survival in the face of infection.

Our data show that treatment of pDCs with type 1 IFNs leads to increases in FAO-dependent SRC, which in CD8+ T cells and macrophages is a mark of increased longevity (Huang et al., 2014; van der Windt et al., 2012). Therefore we reasoned that pDC numbers would be reduced in virus-infected mice following treatment with etomoxir. Our finding that etomoxir treatment resulted in a reduction in pDC numbers over untreated infected mice is consistent with this assumption. However, infection, or the injection of TLR agonists, results in an equal or greater reduction in pDC numbers compared to in naïve mice, an effect that has been shown to be due to the induction of intrinsic apoptosis by type 1 IFNs (Swiecki et al., 2011). It is conceivable that type 1 IFN-induced pro-apoptotic pathways are to some extent mitigated by simultaneously-induced increases in mitochondrial fitness to prolong pDC lifespan. Our finding that type 1 IFNs promote SRC in CD8+ T cells suggests that these cytokines should enhance TMEM cell development, a conclusion that is consistent with reports on the beneficial effects of type 1 IFNs on CD8+ T cell survival (Kolumam et al., 2005).

As expected, CpGA strongly induced expression of type 1 IFNs. This occurs via a pathway that includes MyD88, IKKα and IRF7, with the subsequent amplification of type 1 IFN production by autocrine IFNAR signaling by the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex, which initiates chromatin remodeling and the recruitment of transcription factors to ISG promoter sites (Ivashkiv and Donlin, 2014; Swiecki and Colonna, 2015). IFNAR dependent expression of ISGs is subject to extensive regulation and how PPARα signaling and other facets of FAO and OXPHOS are promoted by type 1 IFNs is currently unclear. However, chromatin remodeling is regulated by the posttranscriptional modification of histones by acetylation. Acetate for acetylation as well as for FAS are generated through the same pathway downstream of glycolysis and the export of citrate from the TCA cycle (Wellen et al., 2009), so we speculate that the metabolic changes reported here serve to support epigenetic changes that are critical for the accentuation of type 1 IFN production downstream of IFNAR.

Given the importance of type 1 IFNs during infection (McNab et al., 2015), cancer (Zitvogel et al., 2015) and autoimmune diseases (Crow, 2010), there is a clinical need for approaches that can alter downstream effects of these cytokines. Our findings suggest that inhibiting FAO and OXPHOS may allow the amelioration of diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, associated with excessive type 1 IFN production and/or pDC activation (Sisirak et al., 2014). Metabolic targeting may provide a powerful adjunct to more conventional therapies in these setting. Additionally, approaches that accentuate FAO and OXPHOS may have clinical application in the treatment of viral infections.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

WT C57BL6 (B6), Ifnar−/− B6, and OT-I B6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were maintained at Washington University under SPF conditions under protocols approved by the IACUC and used for experiments between 6 and 12 weeks of age.

In vitro DC differentiation

DCs were generated from bone marrow in the presence of Flt3L (PeproTech, 160 ng/ml) in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine for 9 days (Naik et al., 2007). CD11cintSiglec H+ B220+ pDCs, and CD11chiSIRPα+ cDCs were isolated by FACS using a BD FACSaria II.

DC culture

DCs were cultured in 1.5 × 105 cells/well in 200 μl, and where indicated pre-treated for 24h with CpG-A (5 μg/mL; InvivoGen), IFN-α (100U/ml, PBL Assay Science), Imiquimod (6 μM, Calbiochem), Poly I:C (25 μg/ml, Sigma), etomoxir (200 μM, Tocris Biochemicals), 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid (TOFA; 20 μM, Sigma Aldrich), UK-5099 (50 μM, Sigma Aldrich), MAR1-5A3 (5 μg/ml, Leinco Technologies) or GW6471 (3 μM; Tocris Biochemicals). pDCs were incubated overnight with 100 μM Gemfibrozil or 100 μM Muraglitazar (Santa Cruz). IFNα was detected using a mouse IFNα elisa kit (PBL assay science). TNF-α and IL-6 were measured using BD™ Cytometric Bead Array (CBA).

Virus infection

LCMV Arm was grown, stored and quantified according to published methods (Pearce et al., 2004) and injected i.p. at a dose of 2 × 105 plaque forming units per mouse. Mice were treated with etomoxir (20 mg/kg) i.p. and sacrificed on day 3. Tissues were collected and frozen at −80 °C for subsequent analysis.

CD8+ T cells culture

Splenocytes from naïve OT-1 mice were activated with SIINFEKL peptide and 100U/ml IL-2 for 3 days and subsequently cultured with 100 U/ml of IL-2 or 10 μg/ml IL-15 for another 3 days. Activated cells were treated with IFNα (100U/ml) for 24h prior to EFA.

PDV epithelial cell culture

PDV murine keratinocytes (CLS, Heidelberg, Germany) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 μM Non-Essential Amino Acid (NEAA), and 2 mM L-glutamine. PDV cells were infected with LCMV Arm for 2 h, washed, and cultured in medium with IFNα, and/or inhibitors as described above for DC culture.

Retroviral transduction

Retroviral transduction of pDCs was accomplished using a protocol described previously (Krawczyk et al., 2010). Sequences for short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were obtained from Open Biosystems and cloned into LMP retroviral vectors expressing either huCD8 or GFP. Transduced cells were gated or sorted based on GFP or huCD8 expression.

Metabolism Assays

An XF-96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) was used for EFA, of pDCs (1.5 × 105 cells/well) or PDV (3× 104 cells/well) as described (Everts et al., 2012). For mitochondrial fitness tests, OCR was measured sequentially at basal, and following the addition of 1 μM oligomycin, 1.5 μM FCCP (fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone), 200μM etomoxir (in some cases) and 100 nM rotenone + 1 μM antimycin A. An ATP determination kit (Life technologies) was used to measure ATP in cell extracts (104 cells/μl). Flow cytometry was used to measure mitochondrial membrane potential in cells stained with TMRM (50nM, Life Technologies).

Flow cytometry

Antibodies specific for CD11c (N418), Siglec H (551), B220 (RA3-6B2) and INFAR were from eBioscience. Antibody specific for CD86 (GL1) was from BD, and antibody specific for PPARα was from Santa Cruz.

Immunoblotting

pDCs and heart were lysed in Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling technology). Equivalent amounts of protein (quantified by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and probed with antibodies against GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology) and PPARα (Santa Cruz).

RT-qPCR

RNA isolations were done using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Single strand cDNA was synthesized using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using SYBR Green (LCMV gp expression) or Taqman (PPARα expression) in an Applied Biosystems 7000 system was used to measure transcripts. Primers for PPARα (Mm00440939-m1) β-actin (Mm00607939-s1) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Expression of PPARα mRNA was normalized to the expression of β-actin. Mouse LCMV gp primers: CAT TCA CCT GGA CTT TGT CAG ACTC (Fwd) and GCA ACT GCT GTG TTC CCG AAAC (Rev). Mouse HPRT primers: AAGGACCTCTCGAAGTGTTGGATA (Fwd) and CATTTAAAAGGAACTGTTGACAACG (Rev). The qRT-PCR was performed in duplicate for each sample. The quantitation of the results was performed by the comparative Ct (2−[delta][delta]Ct) method. The Ct value for each sample was normalized by the value for β-actin or HPRT gene.

RNA-sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

mRNA was extracted using oligo-dT beads (Invitrogen) cells that had been stimulated for 24 hours. cDNA synthesis, sequencing and sequence analysis were performed as described (Jha et al., 2015). For Fig. 2, genes differentially expressed in CpGA-stimulated vs. resting pDCs (fold change ≥ 2 or ≤ −2, p <0.05) were analyzed. Differentially expressed genes that were present in INTERFEROME (http://www.interferome.org) were identified (Rusinova et al., 2013). Overlapping genes were analyzed for GO biological processes using DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) (Huang da et al., 2009). Differentially expressed genes (fold change ≥ 2 or ≤ −2) of IFNα-activated pDCs vs. resting pDCs were analyzed (Fig. 7). Searching with the key words metabolism, glycolysis, FAO, oxidative phosphorylation, lipid uptake, lipid synthesis, FAS, FA uptake, differentially expressed genes that encode proteins involved in metabolic pathways, as defined by the RGD genes database (http://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/search/genes.html) (Shimoyama et al., 2015) were identified. Overlapping genes were archived for network analysis. A network of interactions was constructed using STRING 10 (Shimoyama et al., 2015). Pathway enrichment analysis based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was performed and significantly enriched terms based on low p-values and false discovery rates were used for further analysis. The resulting network of genes was annotated and modified using Cytoscape (Cline et al., 2007). In this analysis, thicker edges represent interactions with higher support form published literature. Raw and processed sequencing data are deposited to PubMed GEO under GSE81889.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism (v5). Two-group comparisons were assessed using unpaired or, where indicated, paired two-tailed Student’s t-tests. The use of these tests was justified based on assessment of normality and variance of the distribution of the data. Differences were considered significant when p-values < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Type 1 IFNs promote fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).

In CpG-stimulated pDCs, FAO is enhanced due to autocrine type 1 IFN signaling.

Increased FAO induced in pDCs by CpG-stimulation is essential for cellular activation.

Type 1 IFN-induced FAO is partly PPARα -dependent and has anti-viral properties.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexey Sergushichev, Wei Yang, Skip Virgin, Joel Schilling, Stanley Huang, David O’Sullivan, Ramon Klein Geltink, Michael Diamond, Kathy Sheehan, Robert Schreiber and the Genome Technology Access Center at Washington University for their generous help and advice. Supported by NIH grants to E.J.P. (CA164062, AI110481) and E.L.P (AI091965, CA158823), The Max Planck Society, a National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant to M.C. (RG4687A1), a Shanghai Rising-Star Program grant to D.W. (13QA1400800), an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship to M.D.B., and a VENI grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and Marie Curie CIG from European Union to B. E.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

D.W., B.E., D.S., E.L.P, M.C. and E.J.P designed the research. D.W., B.E., D.S., Q.C., J.Q., M.B., A.M.S., A.P., C-H.C., Z.L., M.N.A., E.L.P, M.C. and E.J.P. performed experiments and/or analyzed data. D.W., B.E., D.S., M.B., E.L.P., M.C. and E.J.P. prepared the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Asselin-Paturel C, Brizard G, Chemin K, Boonstra A, O’Garra A, Vicari A, Trinchieri G. Type I interferon dependence of plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation and migration. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1157–1167. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc M, Hsieh WY, Robertson KA, Watterson S, Shui G, Lacaze P, Khondoker M, Dickinson P, Sing G, Rodriguez-Martin S, et al. Host defense against viral infection involves interferon mediated down-regulation of sterol biosynthesis. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. The Biochemical journal. 2011;435:297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Cohen P. The TRAF-associated protein TANK facilitates cross-talk within the IkappaB kinase family during Toll-like receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17093–17098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114194108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline MS, Smoot M, Cerami E, Kuchinsky A, Landys N, Workman C, Christmas R, Avila-Campilo I, Creech M, Gross B, et al. Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nature protocols. 2007;2:2366–2382. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow MK. Type I interferon in organ-targeted autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Arthritis research & therapy. 2010;12(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/ar2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai P, Cao H, Merghoub T, Avogadri F, Wang W, Parikh T, Fang CM, Pitha PM, Fitzgerald KA, Rahman MM, et al. Myxoma virus induces type I interferon production in murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells via a TLR9/MyD88-, IRF5/IRF7-, and IFNAR-dependent pathway. Journal of virology. 2011;85:10814–10825. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00104-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvergne B, Michalik L, Wahli W. Transcriptional regulation of metabolism. Physiological reviews. 2006;86:465–514. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear Receptors, RXR, and the Big Bang. Cell. 2014;157:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts B, Amiel E, Huang SC, Smith AM, Chang CH, Lam WY, Redmann V, Freitas TC, Blagih J, van der Windt GJ, et al. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKKε supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:323–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts B, Amiel E, van der Windt GJ, Freitas TC, Chott R, Yarasheski KE, Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Commitment to glycolysis sustains survival of NO-producing inflammatory dendritic cells. Blood. 2012;120:1422–1431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-419747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul EJ, Wanjalla CN, Suthar MS, Gale M, Wirblich C, Schnell MJ. Rabies virus infection induces type I interferon production in an IPS-1 dependent manner while dendritic cell activation relies on IFNAR signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001016. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrick DA, Neilson A, Beeson C. Advances in measuring cellular bioenergetics using extracellular flux. Drug discovery today. 2008;13:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greseth MD, Traktman P. De novo fatty acid biosynthesis contributes significantly to establishment of a bioenergetically favorable environment for vaccinia virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004021. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap AP. The mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Kinetics and specificity for substrates and inhibitors. The Biochemical journal. 1975;148:85–96. doi: 10.1042/bj1480085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton NS, Randall G. Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature protocols. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O’Sullivan D, Nascimento M, Smith AM, Beatty W, Love-Gregory L, Lam WY, O’Neill CM, et al. Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:846–855. doi: 10.1038/ni.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Wang YH, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors/type I interferon-producing cells sense viral infection by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2014;14:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nri3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, et al. STRING 8–a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A, Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E, Chmielewski K, Stewart KM, Ashall J, Everts B, et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 2015;42:419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffre O, Nolte MA, Sporri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory signals in dendritic cell activation and the induction of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:234–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J Exp Med. 2005;202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk CM, Holowka T, Sun J, Blagih J, Amiel E, DeBerardinis RJ, Cross JR, Jung E, Thompson CB, Jones RG, Pearce EJ. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115:4742–4749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O’Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2015;15:87–103. doi: 10.1038/nri3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser TS, Schieffer D, Cherry S. AMP-activated kinase restricts Rift Valley fever virus infection by inhibiting fatty acid synthesis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002661. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger J, Bennett BD, Parikh A, Feng XJ, McArdle J, Rabitz HA, Shenk T, Rabinowitz JD. Systems-level metabolic flux profiling identifies fatty acid synthesis as a target for antiviral therapy. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26:1179–1186. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik SH, Sathe P, Park HY, Metcalf D, Proietto AI, Dakic A, Carotta S, O’Keeffe M, Bahlo M, Papenfuss A, et al. Development of plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell subtypes from single precursor cells derived in vitro and in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1217–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill LA, Pearce EJ. Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J Exp Med. 2016;213:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan D, van der Windt GJ, Huang SC, Curtis JD, Chang CH, Buck MD, Qiu J, Smith AM, Lam WY, DiPlato LM, et al. Memory CD8(+) T cells use cell-intrinsic lipolysis to support the metabolic programming necessary for development. Immunity. 2014;41:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantel A, Teixeira A, Haddad E, Wood EG, Steinman RM, Longhi MP. Direct type I IFN but not MDA5/TLR3 activation of dendritic cells is required for maturation and metabolic shift to glycolysis after poly IC stimulation. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce EJ, Everts B. Dendritic cell metabolism. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2015;15:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nri3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce EL, Shedlock DJ, Shen H. Functional characterization of MHC class II-restricted CD8+CD4- and CD8-CD4- T cell responses to infection in CD4−/− mice. Journal of immunology. 2004;173:2494–2499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinova I, Forster S, Yu S, Kannan A, Masse M, Cumming H, Chapman R, Hertzog PJ. Interferome v2.0: an updated database of annotated interferon-regulated genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1040–1046. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoyama M, De Pons J, Hayman GT, Laulederkind SJ, Liu W, Nigam R, Petri V, Smith JR, Tutaj M, Wang SJ, et al. The Rat Genome Database 2015: genomic, phenotypic and environmental variations and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D743–750. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal FP, Kadowaki N, Shodell M, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly PA, Shah K, Ho S, Antonenko S, Liu YJ. The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science. 1999;284:1835–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisirak V, Ganguly D, Lewis KL, Couillault C, Tanaka L, Bolland S, D’Agati V, Elkon KB, Reizis B. Genetic evidence for the role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1969–1976. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiecki M, Colonna M. The multifaceted biology of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2015;15:471–485. doi: 10.1038/nri3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiecki M, Wang Y, Vermi W, Gilfillan S, Schreiber RD, Colonna M. Type I interferon negatively controls plasmacytoid dendritic cell numbers in vivo. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2367–2374. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Windt GJ, Everts B, Chang CH, Curtis JD, Freitas TC, Amiel E, Pearce EJ, Pearce EL. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8+ T cell memory development. Immunity. 2012;36:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga T, Czimmerer Z, Nagy L. PPARs are a unique set of fatty acid regulated transcription factors controlling both lipid metabolism and inflammation. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1812:1007–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Swiecki M, McCartney SA, Colonna M. dsRNA sensors and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in host defense and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:74–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science. 2009;324:1076–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1164097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim HY, Yang Y, Lim JS, Lee MS, Zhang DE, Kim KI. The mitochondrial pathway and reactive oxygen species are critical contributors to interferon-alpha/beta-mediated apoptosis in Ubp43-deficient hematopoietic cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;423:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York AG, Williams KJ, Argus JP, Zhou QD, Brar G, Vergnes L, Gray EE, Zhen A, Wu NC, Yamada DH, et al. Limiting Cholesterol Biosynthetic Flux Spontaneously Engages Type I IFN Signaling. Cell. 2015;163:1716–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G. Type I interferons in anticancer immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2015;15:405–414. doi: 10.1038/nri3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.