Abstract

Rational

Incarcerated transgender individuals may need to access physical and mental health services to meet their general and gender-affirming (e.g., hormones, surgery) medical needs while incarcerated.

Objective

This study sought to examine correctional healthcare providers’ knowledge of, attitudes toward, and experiences providing care to transgender inmates.

Method

In 2016, 20 correctional healthcare providers (e.g., physicians, social workers, psychologists, mental health counselors) from New England participated in in-depth, semi-structured interviews examining their experiences caring for transgender inmates. The interview guide drew on healthcare-related interviews with recently incarcerated transgender women and key informant interviews with correctional healthcare providers and administrators. Data were analyzed using a modified grounded theory framework and thematic analysis.

Results

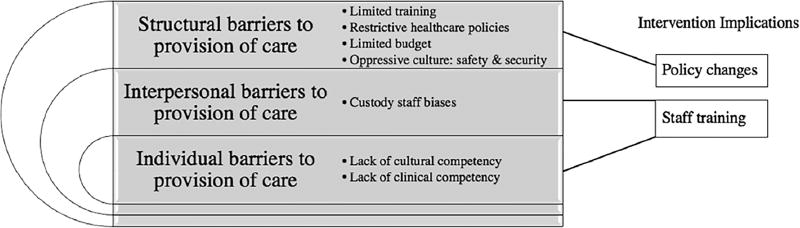

Findings revealed that transgender inmates do not consistently receive adequate or gender-affirming care while incarcerated. Factors at the structural level (i.e., lack of training, restrictive healthcare policies, limited budget, and an unsupportive prison culture); interpersonal level (i.e., custody staff bias); and individual level (i.e., lack of transgender cultural and clinical competence) impede correctional healthcare providers’ ability to provide gender-affirming care to transgender patients. These factors result in negative health consequences for incarcerated transgender patients.

Conclusions

Results call for transgender-specific healthcare policy changes and the implementation of transgender competency trainings for both correctional healthcare providers and custody staff (e.g., officers, lieutenants, wardens).

Keywords: Transgender, Incarceration, Healthcare, Prisons and jails, Corrections

1. Introduction

Transgender individuals face high rates of victimization and violence, substance use, mental health issues and suicide attempts, and incarceration relative to the general population (Bradford et al., 2013; Stotzer, 2009; Yang et al., 2015). Structural stigma exacerbates these disparities (White Hughto et al., 2015), which is perhaps most evident in the overrepresentation of transgender individuals in the U.S. prison system. Barriers to employment and secure housing drive involvement in illegal economies, including sex work and substance use, for some transgender people, which in turn places them at risk for arrest and incarceration (Fletcher et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2011; Nadal et al., 2012; Reback and Fletcher, 2014; Wilson et al., 2009). Once incarcerated, transgender individuals are placed in either male or female facilities according to their genitalia (Sevelius and Jenness, 2017). Due to sex-segregation in U.S. jails and prisons, the number of incarcerated transgender individuals is unknown. Yet, it is estimated that about 16% of transgender people (21% of transgender women) have been incarcerated in their lifetime (Grant et al., 2011), compared to estimates ranging from 2.8% to 6.6% of the general U.S. population (Bonczar, 2003; Glaze and Kaeble, 2011).

Every year that a member of the general population is incarcerated is associated with a two-year reduction in life expectancy (Patterson, 2013). For transgender individuals, incarceration experiences may lead to particularly deleterious health outcomes. Extensive research highlights the heightened prevalence of victimization among incarcerated transgender individuals, including severe verbal harassment, purposeful humiliation, physical assault and beatings, unwanted sexual touching, unwarranted strip searches and pat-downs, and forcible penetrative sex from other inmates and custody staff (e.g., corrections officers, lieutenants, wardens) (Bassichis and Spade, 2007; Edney, 2004; Jenness et al., 2007; Okamura, 2011; Rosenblum, 1999; Sumner and Sexton, 2015). Further, transgender individuals likely enter the correctional system with poorer health than the general population due to aforementioned health disparities.

Incarcerated transgender people, like all detainees, may need to access physical and mental health services to meet their general healthcare needs; some transgender inmates also require medical care in order to “transition” or medically affirm their gender. Medically affirming one's gender can include the use of exogenous hormone therapy (e.g., estrogen) or surgery to masculinize or feminize the body, with hormone therapy often being the first and sometimes only gender-affirming medical intervention sought (Coleman et al., 2012). Failure to treat symptoms associated with gender dysphoria can result in depression, suicidality, auto-castration, and death (Coleman et al., 2012; Routh et al., 2015).

Structural barriers (i.e., laws, policies, regulations) impede adequate healthcare provision for incarcerated transgender individuals. As of 2015, just seven states had a policy allowing sex-reassignment surgery (SRS) for transgender inmates (Routh et al., 2015); until January 2017, when the California prison system funded SRS for a transgender inmate under their care, no transgender inmate had been successful in obtaining SRS (Thompson, 2017). Medically necessary hormone therapy (Coleman et al., 2012) is often equally difficult for transgender people to procure while incarcerated. A national study investigating the incarceration experiences of transgender inmates (N = 129; 97% transgender women) across 24 states found that just 14% of the participants reported accessing cross-sex hormones (Brown, 2014). Qualitative research conducted with recently incarcerated transgender women (N = 20) found that correctional policies required transgender women to prove that prior to incarceration, a physician had prescribed them hormones. This policy presented challenges for many of the women, some of whom had not been regularly engaged in care or had been taking “street hormones” (e.g., acquired through friends or online) prior to being incarcerated (White Hughto et al., in press-a). Due to the high rates of illicit street hormone use among low income transgender individuals (Rotondi et al., 2013; Sanchez et al., 2009) and widespread policies requiring documentation of physician-prescribed medications (Brown and McDuffie, 2009; Routh et al., 2015), a high percentage of incarcerated transgender individuals are forced to stop their hormone regimen once incarcerated. While such structural barriers to healthcare are relatively well-documented in the literature, less is known about the quality of care transgender inmates receive from correctional healthcare providers.

Individual-level (i.e., lack of provider knowledge and bias) and interpersonal-level (i.e., interactions with custody staff) barriers may also impede adequate healthcare provision for incarcerated transgender individuals. A recent qualitative study with 20 formerly incarcerated transgender women found that correctional healthcare providers lacked the ability to provide gender-affirming care due to transgender-related biases and had limited knowledge of appropriate care (White Hughto et al., in press-a). Tenets of gender-affirming care for transgender individuals include access to transition-related medical care (i.e., hormone therapy, surgeries) in a culturally-tailored environment provided by knowledgeable healthcare providers (Reisner et al., 2015). Similarly, a 2009 survey of transgender and gender non-conforming inmates in Pennsylvania (N = 59) found that 42.4% of the sample believed their medical needs were not taken seriously by medical staff (Emmer et al., 2011). Further, studies have shown that there is often tension between custody and care in the prison system, in which the goals of custody staff (i.e., safety, security, management) are at odds with the treatment goals of prison healthcare providers (Short et al., 2009; Willmott, 1997); however, no research to date has investigated this conflict in regards to transgender patient care.

While research has documented the healthcare experiences of transgender inmates, to our knowledge, no study to date has sought to understand correctional healthcare providers' experiences providing care to transgender patients from the perspective of providers themselves. By understanding the perspective of correctional healthcare providers in their care of transgender inmates, this study intends to provide information to better intervene at the staff-level to influence adequate provision of care. This study comprised a qualitative investigation to better understand healthcare provision for incarcerated transgender individuals from the perspective of correctional healthcare providers. The aim of this study was to investigate healthcare provider's knowledge, attitudes and experiences providing healthcare to transgender individuals in correctional settings. Results were expected to inform future interventions to ensure access to quality gender-affirming care for incarcerated transgender individuals.

2. Method

2.1. Sample

Twenty correctional healthcare providers were recruited to participate in an in-depth, semi-structured interview to examine their knowledge, attitudes, and experiences caring for transgender inmates. Eligible participants were age 18 years and older; self-identified as a correctional healthcare provider (e.g., physician, nurse, psychologist, mental health counselor, social worker); worked within a correctional facility in New England; and had prior experience caring for or interacting with one or more transgender inmates. All correctional healthcare providers worked in state prisons and were employed by an external healthcare organization affiliated with a local university. Following IRB approval, an administrator within the central branch of the affiliated healthcare organization emailed a recruitment flyer to all correctional healthcare providers in the state. Interested providers contacted study investigators for additional information.

2.2. Procedures and data analysis

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between January and February 2016. Interviews were conducted by the first and second author and lasted between 25 and 75 min. The interview guide was created in collaboration with the authorship team; it drew on healthcare-related interviews with recently incarcerated transgender women (White Hughto et al., in press-a) and formative key informant interviews with correctional healthcare providers and administrators. Drafts of the interview guide were reviewed for cultural relevance to the correctional system (e.g., use of appropriate terms and language used by correctional staff). Prior to data collection, the interview guide was pilot tested with three correctional healthcare providers to finalize the interview guide. The final interview guide included themes related to the providers' background, the prison setting in which they worked, and providers' experiences caring for transgender people, including perceived facilitators and barriers to caring for transgender people in correctional settings. To limit social desirability, interviews were conducted by phone and were not audio recorded, as recommended by research showing that audio recording can cause interview participants to become less comfortable and more formal in their responses (Al-Yateem, 2012). To ensure exact recording of study findings, one of the authors interviewed the participant while the other author transcribed the conversation verbatim. Interview data were reviewed throughout the recruitment process. Once thematic saturation was reached, no new participants were recruited for participation. All participants provided verbal consent prior to participation. Participants received a $20 gift card for their time. All study activities were approved by Yale Human Subject Committee.

Data were analyzed in Dedoose using a modified grounded theory framework (Strauss and Corbin, 1994) and thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Specifically, the first and second authors, both trained in qualitative methodology, open-coded the transcripts for broad analytic themes. Using a priori codes derived from the thematic content areas of the interview guide (e.g., personal background, prison context, experiences with transgender patients) and emergent codes derived from open coding, the first and second author worked collaboratively to organize the data into a fixed code structure. This code structure was iteratively refined in a series of meetings. Once the codebook was finalized, the first and second authors coded the transcripts using Dedoose software (Dedoose, 2016). The authors met frequently throughout the coding process to discuss coding questions and ensure consistent application of codes.

3. Results

3.1. Conceptual model

An adapted social-ecologic model demonstrating the multiple levels at which transgender-related stigma operates (White Hughto et al., 2015) was used to conceptualize the emergent themes and intervention implications (see Fig. 1). This conceptual model illustrates how structural, interpersonal, and individual-level factors impede provision of gender-affirming care to transgender patients. Specifically, structural barriers such as lack of training, restrictive healthcare policies, limited budget, and an unsupportive prison culture work at the institutional level to impede access to care. Interpersonal barriers refer to interactions between healthcare providers and biased custody staff that restrict adequate care for transgender inmates. Finally, individual barriers refer to providers' personal knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs that may inhibit their adequate care for transgender inmates.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of barriers to provision of care for transgender inmates among correctional healthcare providers.

3.2. Demographics

The majority of the samplewas female (n = 18; 90%). The sample consisted of three medical doctors (15%), three nurses (15%), three psychologists (15%), eight social workers (40%), two mental health counselors (10%), and one clinical administrator (5%). A large majority of participants worked in prisons housing only male inmates (70%), which reflects the ratio of male to female prisons in the U.S (Glaze and Kaeble, 2011). Participants had worked in the prison system for an average of 7.71 years (SD = 5.16; range: 1.5–21). All participants worked at a state correctional facility ranging from medium security (level 3) to maximum security (level 5).

3.3. Structural barriers

Structural barriers, including limited training, restrictive transgender healthcare policies, limited budget, and the cultural mandate of safety and security above patient care impeded the ability of correctional healthcare providers to provide supportive, gender-affirming care for transgender inmates.

A primary institutional barrier to transgender-affirming care was lack of transgender healthcare training. One social worker who worked at a male facility highlighted that the only way to gain adequate knowledge about transgender health was to independently find training outside the prison facility. She explained, “I have done trainings on my own. [Transgender health] was briefly covered in an LGBT training, and then just my own kind of readings. But [the prison] doesn't offer anything in particular about it.” Another social worker who had worked at both male and female facilities explained that the lack of training on transgender issues often led to confusion among healthcare staff about gender-affirming care. The social worker explained:

Frequently, like half of the healthcare staff might refer to the person as “she” and the other staff might refer to them as “he.” Or if the person has changed their name, some of the healthcare staff might use the name of their choice, while other staff will use the name given on their birth certificate. No one really knows, what's the right thing to do? … So I think that causes a lot of trauma for the clients. So maybe some training about what specifically would be most appropriate in that situation might be helpful.

These providers illustrate how lack of training on how to appropriately interact with transgender patients caused confusion among staff and also likely adversely impacted transgender patients.

Restrictive healthcare policies also acted as structural barriers to adequate care for transgender inmates. Almost all healthcare providers highlighted that unless a transgender inmate could provide documentation of prescribed hormones by a physician, hormone therapy ceased upon incarceration. This policy negatively impacted transgender patients who were taking hormones outside a provider's care (e.g., street hormones) or who could not secure the appropriate documentation of their prior hormone use. A social worker who had been working in corrections for eight years explained the deleterious mental health impact of hormone cessation on one of her transgender clients. She stated:

They can't continue [street hormones]. That actually happened with a client of mine. [The client] was getting his hormones out in California. Not really sure from where, but it seemed like a drop-in place for prostitutes, so they didn't really keep any records, and we couldn't verify anything, and so they weren't continued. It was devastating because that client began to grow facial hair again and they just were devastated. It impacts their depression and suicidality because they just feel so out of place.

This statement highlights how policies requiring proper documentation of prior prescribed hormone use can prevent transgender patients from accessing hormone therapies in prison with adverse mental health consequences. Additionally, while the social worker was sympathetic to the impact that lack of access to care had on her patient and was well-meaning in her treatment, her use of male pronouns to refer to her female-identified patient highlights a need for further cultural competency training in regards to gender-affirming interactions.

Providers also faced structural barriers to providing care in their inability to initiate hormone therapy for transgender inmates with gender dysphoria. One physician who had been working in corrections for ten years described the challenges her transgender patient faced when attempting to initiate hormone therapy. She explained,

I encountered a transgender woman in the male facility … This inmate had decided to transition while incarcerated and had partially begun the process as far as changing her gender expression, and using different pronouns and name. She was still in the male facility due to her anatomy. She wasn't able to start hormones because she had not been on them on the outside.

This physician's statement highlights how prison policies limited the ability of correctional providers to help transgender patients medically affirm their gender, even for transgender inmates who had already socially affirmed their gender inside the prison (i.e., by living full-time in their identified gender).

Correctional healthcare providers also cited the limited prison healthcare budget as a structural barrier to providing gender-affirming care. For instance, many correctional healthcare providers explained that the hormones' expense limited transgender patients' access to them. One clinical administrator who had worked in a male facility for eight years highlighted that although healthcare providers knew that transgender inmates had specific medical needs, it was often simply too costly to treat them. She explained:

There are limitations we have in the system with the budget that we're given by the state. It speaks volumes that our costs are different to house someone for a year with a medical diagnosis. Transgender is expensive. It takes a lot of provider time and we have 20,000 inmates. No one denies it's there and it's something that needs to be addressed but the venue is the challenge and not the place for it.

Other providers saw hormone therapy as a controversial issue that would not be prioritized in light of the limited institutional budget for healthcare. For example, one psychologist stated, “Hormone therapy is still controversial. Still a hard sell about starting that process [initiating hormone therapy while incarcerated] in terms of cost. There would need to be a very in-depth assessment performed before a prison could even consider providing hormone therapy without a prescription. We are just not equipped for it.” The controversial nature of hormone use, together with the state's limited budget was further articulated by several providers, including a medical nurse who had worked in a male facility for eight years and who spoke bluntly about the role that prison finances play in the medical care of transgender inmates. She stated, “The state wouldn't pay [for hormones] because it's expensive. The state cares about something that would kill them.” Provider narratives suggested that concerns about the limited state budget were often used as a justification to withhold hormones.

The overarching prison culture that prioritizes physical safety and security over treatment emerged as the dominant structural barrier to provision of adequate healthcare to transgender inmates. Nearly all providers cited that the cultural mandate to ensure safety and security of the facility was prioritized over the healthcare of individual inmates. One mental health counselor who worked at a male facility explained how the focus on security impeded her ability to provide care. She stated, “The primary focus [of the facility] will be safety and everything comes second to that. So it's hard that safety comes first and sometimes that takes precedent over what's needed including therapy or what's culturally appropriate.” One social worker highlighted the impact that a focus on security had on treatment provision during therapy sessions. She explained, “[During counseling], the inmate is often handcuffed behind his back. I have often wiped a tear or held a tissue over their nose, because they can't. It's just that safety and security trumps all treatment.”

Most interviewees explained that the safety and security mandate actually served to make their patients psychologically worse than when they arrived at the facility. One psychologist who had been working at a male facility for less than two years explained her frustration with the cultural focus on safety and security over treatment. She noted, “Certainly, no one is thinking about long term, that most of these guys are getting out. And frankly we're making them worse. It's a disaster, really. It really is.” While most providers understood the negative health implications of prioritizing security over medical treatment, a handful of providers supported the prison system's claims that safety outweighs treatment. One male mental health counselor noted:

I can see it's difficult on both sides of the inmates and the staff on being able to accommodate appropriately to the LGBTs, transgender, all the letters … what it falls back on is that you're an inmate before anything and safety of everyone comes before anyone else. If they're gonna try to come out and everything, and be all effeminate, and trying to attract other inmates, that's dangerous for them. That's a huge danger there that they need to realize, staff needs to realize. We need to look at this from a safety standpoint.

This counselor accepted the overarching culture that safety and security must come before all treatment and care provision; indeed, he viewed transgender women's coming out process as a threat to their personal safety and the security of the facility. The cultural mandate of safety and security above patient care, along with limited budget, restrictive transgender healthcare policies, and limited training all served as structural barriers to the provision of adequate care for transgender inmates.

3.4. Interpersonal barriers

Interpersonal interactions between custody staff and healthcare providers emerged as a clear barrier to appropriate, gender-affirming care of transgender patients. Almost all healthcare providers noted that custody staff biases towards both healthcare providers and transgender inmates obstructed healthcare providers’ ability to adequately care for their transgender patients.

A recurrent theme among providers was that custody staff did not respect them in their role as healthcare providers. Indeed, custody staff bias toward healthcare providers routinely impeded providers' ability to provide adequate care to vulnerable patients, including transgender inmates. One social worker who worked at a male facility explained, “I wish they understood what we do. I think a lot of them think it's psychobabble bullshit and if we didn't have psychologists we wouldn't need psychologists. They think nothing of cancelling a group or cancelling one-on-one stuff. We're guests in their house.” This provider illustrates how lack of understanding and sensitivity on the part of custody staff often resulted in interrupted patient care.

A number of healthcare providers reported conflicts with custody staff over appropriate care of transgender inmates. One social worker explained the reaction she received when she tried to address a transgender woman by the appropriate name and pronoun in a male prison. She recalled:

With respect to the transgender piece, I remember one of the lieutenants was talking about somebody, and I referred to the person as ‘she’ and he goes, ‘She?’ and I said, ‘Yeah we refer to them as they self-identify.’ And he goes, ‘Of course you would. We call them ‘It’.’ And that's coming from the supervisors. If that's your supervisor and you're one of the officers, then, you know, you're going to pick up that kind of attitude as well.

This social worker showcases the lack of respect that some custody staff have for gender-affirming providers. The quotation also highlights the para-militaristic hierarchy within the prison and the ways in which this hierarchy negatively influenced custody staff attitudes towards transgender patients and their providers. Indeed, many correctional healthcare providers explained that continued advocacy for any patient could lead them being labeled as an “inmate lover” by custody staff. One psychologist who worked in a male prison explained:

It's hard because I have to walk a fine line, I have to, like, align myself with custody, while still hearing the inmates too. Because if you get looked at by custody that you're an – they'll call you an “inmate lover” – then they'll shun you. But I see things here every day that I wish I didn't have to see. They'll yell at them, call them a piece of shit, they're rough with them. It's a very adversarial relationship and with me, they view me very differently.

Like many other providers in the sample, this psychologist described how custody staff looked down upon healthcare providers’ compassion for inmates. Since providers rely on custody staff to escort inmates to medical appointments, any conflict between healthcare providers and custody staff can culminate in lack of patient care. The adversarial relationship between custody staff and both healthcare providers and inmates was highlighted across interviews as an interpersonal barrier to provision of patient care.

3.5. Individual barriers

Individual barriers refer to aspects within correctional healthcare providers themselves that impede their ability to provide competent care. A lack of cultural and clinical competency, stemming from personal bias and lack of knowledge and experience, were the primary individual barriers resulting in inadequate and non-gender-affirming provision of care to transgender inmates.

Cultural competency refers to one's ability to provide culturally sensitive care to patients in a way that acknowledges and respects gender diversity. Many of the healthcare providers lacked such competency. One mental health counselor rationalized that since he was working in a male facility, he viewed all of his patients as males and treated them as such. He explained:

“I have at least two [patients] who prefer to be called Ms. vs. Mr … they prefer ‘call me Ms. XYZ.’ For the most part, we kind of accommodate that to a point, but in general you gotta address them as you see fit. Everybody in the facility is a male. You have male, you have female. There's nothing in-between.” By refusing to acknowledge the existence of transgender inmates in prison, this counselor effectively erased the experiences of his transgender patients. Some providers also viewed any expression of femininity in a male facility or masculinity in a female facility as a show of attention. One social worker explained:

We have the people who are going through the transgender thing and we work with them to get them to not be, like, the “flag-waving, I'm going to change the world” types. That brings problems for them … Particularly for the transgender [females], they really want to be in people's faces about it and it causes problems. I'm kind of okay with it but stop saying it to my face all time, not everything is about that.

The social worker highlights that displays of one's non-concordant gender identity is an issue that causes problems. The view of transgender individuals as “flag-waving” or showing off in a sex-segregated system was a recurrent theme across interviews and suggests a distinct lack of cultural competency among healthcare providers.

Some providers also held misguided beliefs of transgender inmates as innately manipulative. Attempts by transgender inmates to be called by their preferred pronouns or to access gender-affirming care were viewed by many healthcare providers as a manipulative attempt to gain preferential treatment or attention. One nurse who had been working in corrections for ten years elucidated this belief by describing the efforts of transgender inmates to be called by their preferred pronouns. She explained:

We're not supposed to [use female pronouns/names]. We call them by their last names. Yeah, we can't call them “Miss” or anything like that. But they will try. Like, if a new nurse comes on they will try to be, um, treated differently than the rest. Because they want to stand out … when they're in the prison setting, they tend to strut their stuff a lot more and look for more attention more often.

Rather than viewing patients' requests for providers to use female pronouns as a desire for gender affirmation, the nurse instead interpreted these requests as calculating attempts to gain attention. Providers’ perceptions that transgender women seeking gender affirmation were trying to be manipulative suggest a lack of cultural awareness regarding need for gender affirmation and its psychological benefit for transgender individuals.

While many of the providers in the sample lacked cultural competency regarding their transgender patients, a few providers spoke positively about their interactions with transgender inmates. For instance, two participants talked about their office as a “safe space” where they could affirm their transgender patients' gender without fear of being overheard and admonished by custody staff. A psychiatrist who had worked in a male facility for four years explained, “In my office, I can call [transgender patients] he or she.” In regards to affirming her patient's gender, one social worker who had worked in corrections for eleven years explained, “Sometimes I can pick up based on how the they present themselves. Depending on what they want, I will either say ‘Miss or Mr. Williams’.” This social worker also explained her ethos in working with transgender patients: “Don't form a judgment or opinion. They are a person first and foremost.” While these correctional healthcare providers delivered gender-affirming care, statements like these were not in the majority among the providers.

Clinical competency refers to a provider's knowledge of transgender health issues and ability to provide adequate gender-affirming healthcare. One way in which a lack of clinical competency was demonstrated by healthcare staff was through the conflation of being transgender with mental illness. Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis currently included in APA's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, gender dysphoria refers to distress stemming from having a gender identity that is discordant with one's assigned sex at birth, not simply the experience of being transgender. Additionally, transgender individuals do, in fact, report higher rates of mental illness (Reisner et al., 2014, 2016) than cisgender individuals (Kessler et al., 2005), most plausibly explained by their disproportionate exposure to stigma-related stress (White Hughto et al., 2015). However, some healthcare providers conflated transgender identity itself with mental illness, often as some form of a personality disorder or as a consequence of prior trauma or psychosis. Such conflation does not align with current psychiatric conceptualizations and contradicts gender-affirming practice. The inability to distinguish mental illness, trauma, and transgender experience was illustrated across several interviews. One social worker who had worked in corrections for eleven years explained that prison medical staff often did not have a general understanding of the psychology behind transgender issues. She explained, “Oddly enough, you would think that medical staff would have basic knowledge of psychology but they don't, and a lot of them react like, ‘I don't know why they're doing this and they're making a choice or they're making a statement’.” Interviews with other providers corroborated this social worker's account. For instance, one healthcare provider explained that all transgender people seemed mentally ill simply because they protested when their transgender-related healthcare needs were not being met. He stated, “[Being transgender] is certainly not an encouraged thing. Everyone I've seen in here who's transgender seems to have, like, histrionic personality disorder. Like they're screaming about it, ‘I'm transgender!’” Rather than considering that transgender inmates may highlight their identity as a transgender person in an attempt to gain medically necessary treatment, many healthcare providers instead conflated being transgender with being mentally ill. One social worker found it difficult to determine whether being transgender was simply a manifestation of trauma. He explained, “It's hard, too, with the mentally ill, it's hard to tell – there's been quite a few transgenders over the years – the trauma has created them to be transgender, but you don't know if they actually are transgender. It's hard to parse out whether they actually feel like a different sex or if the trauma has just screwed them up.” The view that transgender experience might be caused by prior trauma highlighted the limited clinical competency of some providers.

Several primary care providers also demonstrated limited clinical competency related to transgender care. For example, one physician who had worked in corrections for twenty-one years highlighted that due to a lack of experience, she did not know how to correctly titrate hormones for her transgender patients. She explained: “I have a few [transgender] patients. I never know if you're supposed to titrate [hormones], what they titrate it for, how you approach dosing. I don't have enough experience to know. I usually just keep them what they're on.” This physician highlights how lack of clinical competency surrounding transgender healthcare can result in uninformed clinical decision-making that could have serious health consequences for transgender inmates.

Lack of clinical competence was also demonstrated through providers' provision of medications. Several providers reported withholding patient medications as a means of control. One social worker who had been working in a male prison for eleven years described an account of hormone therapy being withheld by healthcare providers on the basis of the patient's behavior. She explained, “They get the hormone shots. Sometimes they are refused it because they're acting up.” That hormones were refused if a patient was not behaving appropriately highlighted a lack of clinical competency among healthcare providers; indeed, rather than viewing hormone therapy as a medically necessary treatment, some providers instead used it as a tool for controlling the inmates' behavior. Ultimately, a lack of cultural and clinical competency among correctional healthcare providers, stemming from both bias and lack of knowledge and experience, resulted in inadequate provision of care to transgender inmates.

4. Discussion

This study innovatively draws upon the perspectives of correctional healthcare providers to develop a conceptual model of healthcare provision to incarcerated transgender individuals spanning structural, interpersonal, and individual-level barriers. Results can inform future policy and training interventions to improve transgender healthcare provision in the U.S. prison system and globally. Indeed, there is a paucity of research investigating gender-affirming care in prison systems worldwide. Given the novel findings of this study and the relative lack of research in the U.S. and elsewhere, results from this study lay the foundation for national and international work regarding providing gender-affirming healthcare to transgender inmates.

4.1. Structural barriers

Structural factors were among the most frequently cited barriers to the provision of gender-affirming care for transgender inmates. Prior research conducted with formerly incarcerated transgender women cited healthcare provider trainings as an urgent need to improve the quality of care to transgender patients (White Hughto et al., in press-a). The present study complements the perspectives of transgender women themselves by confirming that healthcare providers often evidence a lack of appropriate training. The present study also offers new evidence that while many providers may aspire to provide gender-affirming care, they lack the requisite knowledge to do so.

In addition to a lack of training, findings demonstrated that restrictive policies and limited institutional budget impacted the delivery of transgender care. Indeed, many providers described the ways in which prison policies restricted providers' ability to prescribe hormones to patients who were unable to provide proper documentation of their prior hormone use. Additionally, the restriction on provider's ability or initiate hormones for transgender patients seeking to begin the gender-affirming medical transition process while incarcerated was described. While prior research has documented the presence of restrictive correctional policies pertaining to hormone therapy (Routh et al., 2015) and the impact of such policies on transgender patients (White Hughto et al., in press-a), this study contextualizes the perspectives of transgender patients and policy reports. This study demonstrates that many correctional providers intend to support transgender people in medically affirming their gender, but are inhibited by policies that only allow hormone therapy under certain conditions.

Budget concerns were frequently cited as rationale for curtailing access to gender-affirming medical interventions. Providers explained that gender-related healthcare needs are often ignored or de-prioritized over health needs that are perceived to be less controversial than medical gender affirmation. While substantial increases in prison healthcare spending in the past decade and pressure on state budgets to provide for an aging prison population limits available correctional funds (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2013), hormone therapy is a low-cost intervention (e.g., generic estrogen pills cost less than $15 per month; Consumer Reports, 2008) with documented psychological benefit (White Hughto and Reisner, 2016). Increased access to hormone therapy while incarcerated could therefore reduce clinically significant psychological distress, depression, suicidality, auto-castration, and death by suicide among incarcerated transgender individuals (Brown, 2010, 2014; Colizzi et al., 2014) and in turn reduce the costs associated with these negative health outcomes.

The overarching prison culture that prioritizes safety and security over treatment emerged as the dominant structural barrier to the provision of adequate care to transgender inmates. Providers reported that custody staff – and some healthcare providers – often viewed transgender inmates as high risk for victimization due to their gender expression. This risk for victimization was then utilized as a rationale for discouraging transgender inmates’ gender expression in the name of safety. While transgender inmates are at greater risk of sexual assault and violence than other inmates (Jenness et al., 2007), the prevention of gender expression can lead to deleterious mental health outcomes (Coleman et al., 2012; White Hughto et al., in press-a). Further, transgender inmates likely have poorer mental health at intake than the general prison population, given documented mental health disparities (Clements-Nolle et al., 2001; Mizock and Fleming, 2011). Problematically, however, numerous mental health providers in the present study reported that the safety and security mandate often resulted in loss of adequate psychological treatment, including sudden cancellation of client appointments or unnecessary safety measures that negatively impacted care provision. Correctional systems can have positive health effects on incarcerated individuals by offering direct mental health services and continuity of care upon re-entry (Freudenberg, 2001). However, increased psychological distress stemming from lack of gender-affirming care and inadequate psychological treatment could potentially lead to increased isolation and additional disciplinary citations and ultimately longer periods of incarceration (Bassichis and Spade, 2007; Edney, 2004; Emmer et al., 2011). Increased psychological distress can also impede successful transition to the community and increase recidivism. Indeed, psychological distress is associated with coping through illegal substance use and inability to access medical and mental healthcare or safe and affordable housing, all of which are predictors of recidivism (Baillargeon et al., 2009; Hammett et al., 2001). While the culture of safety and security is ultimately in place to ensure the welfare of all inmates and staff, healthcare must also be prioritized under the umbrella of safety and security in order to ensure the health and wellbeing of vulnerable inmates, including incarcerated transgender individuals.

4.2. Interpersonal barriers

Findings from this research demonstrate that custody staff hold biases toward both transgender inmates and correctional healthcare providers, which inhibits providers' ability to provide adequate patient care. Prior research has documented negative interpersonal interactions between custody staff and transgender inmates from the perspective of transgender patients (Rosenblum, 1999; Sumner and Sexton, 2015; White Hughto et al., in press-a). This study's findings are novel in that they confirm the presence of custody staff bias from the perspective of correctional providers themselves and further reveal that custody staff also hold biased views of correctional healthcare providers. Providers described the ways in which custody staff belittled provider efforts to improve the health of the inmate population by labeling well-meaning providers as “inmate lovers” – a term considered derogatory by custody staff. Correctional healthcare providers also noted that they had to juggle patient healthcare needs while appeasing custody staff who have almost total control over inmate movements (i.e., custody staff decide whether or not a patient receives medical care) (Hatton et al., 2006). A qualitative study with correctional nurses in England reported a similar conflict between “custody vs. care” as nurse participants reported that healthcare was sometimes at odds with the prison regime; however, nurses in that study also expressed solidarity with custody staff and felt supported by them (Powell et al., 2010). This research instead highlighted a strong disconnect between custody staff and healthcare providers. For instance, one healthcare provider expressed exasperation that custody staff seemed to forget that most inmates would be reentering the community. Research has shown that adequate care in prison and continuity of care upon re-entry are vital for rehabilitating prisoners and reducing recidivism, especially for vulnerable inmates with complex health-related needs (Hammett et al., 2001). Further, mental health providers in the current study reported that counseling appointments or group-therapy sessions were often suddenly cancelled by custody staff who did not understand or care about the importance of mental health treatment. Healthcare providers often felt disrespected by custody staff and reported that custody staff undermined patient care; however, providers were afraid to report these issues for fear of being “shunned” by custody staff, which would also limit patient care e an impossible bind.

4.3. Individual barriers

Findings highlight a lack of cultural and clinical competence among many healthcare providers and the ways in which these deficits obstructed correctional healthcare providers' ability to provide gender-affirming care to transgender inmates. Prior research conducted among currently and formerly incarcerated transgender people finds that transgender patients are often treated disrespectfully by correctional healthcare providers, and providers are unprepared to meet transgender healthcare needs (Lydon et al., 2015; White Hughto et al., in press-a). The present study confirms that correctional healthcare providers lack transgender cultural competence, as some providers perceived transgender inmates' requests for social and medical gender affirmation to be manipulative efforts to gain attention. Additionally, many providers reported that they were unable and, in some cases, unwilling to call transgender patients by their preferred name and pronoun in the context of the sex-segregated institution. Further, many providers referred to transgender patients by the wrong pronoun even during study interviews (i.e., used male pronouns to refer to a transgender women). While there were a couple of interviews in which providers spoke about using their office as a “safe space” in which they could appropriately affirm their patients’ gender, overall, interviews suggest that patient-provider interactions were often fraught with language that was not gender-affirming, which seemed to contribute to inadequate patient care. Further, gender-affirming healthcare requests were sometimes brushed aside as simply attention-seeking behavior.

Lack of clinical competence also impeded correctional healthcare provision to transgender inmates. With regard to primary care, many providers lacked basic competencies such as how to initiate and monitor hormone therapy. Providers also evidenced a lack of competency regarding mental health, as some providers conflated mental illness with transgender experience, which likely translates into uninformed healthcare interactions and inadequate mental healthcare provision. The denial of transgender-related care to transgender individuals with co-occurring mental illness can exacerbate patient distress (Mizock and Fleming, 2011), leading to poorer mental health outcomes. Further, some providers intentionally withheld hormones from transgender patients based on perceived poor behavior, highlighting that medication was used as a tool to control transgender patient behavior. Denying medically necessary hormone therapy based on patient behavior is an infringement on the rights of incarcerated patients, and highlights that transgender patients' medical gender affirmation needs are sometimes viewed as unnecessary. The U.S. protects individuals against cruel and unusual punishments under the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Internationally, the UN Nelson Mandela Rules (UNODC, 2015) include protection of vulnerable groups in prison, access to correctional medical and health services, and respect for prisoners' inherent dignity. Consistent with these legal protections and international guidelines, U.S. jails and prisons are obligated to ensure respect for prisoners' inherent dignity, access to medical care, and training for staff on transgender health issues. Together these findings highlight the immediate need for cultural and clinical competence education in order to improve the care of incarcerated transgender individuals.

4.4. Intervention implications and recommendations

Findings suggest that prisons require interventions at multiple levels to improve incarcerated transgender individuals' access to quality gender-affirming care. At the structural level, policy changes are needed to enable staff to use transgender inmates' preferred pronouns (i.e., “he”, “she”, “they”) regardless of the facility in which they are housed (i.e., male vs. female facility). By introducing a simple pronoun-specific guideline that acknowledges transgender experience, transgender individuals will likely experience less distress related to being misgendered. Polices should also be revised to ensure access to hormone therapy regardless of prior documentation of hormone use. Transgender individuals who are taking cross-sex hormones upon incarceration, whether they are street hormones or hormones prescribed by a physician, should be continued. Once incarcerated, current hormone levels can be evaluated by a simple noninvasive saliva swab (Hofman, 2001), which can then be used to tailor medically necessary gender-affirming medical care. For inmates who wish to initiate hormone treatment, primary care providers can follow the informed consent model of care by informing transgender patients of the risks and benefits of hormone therapy and prescribing hormones following patient consent (Cavanaugh et al., 2016). While budget is a consideration in expanding access to hormone therapy, the costs of auto-castration (Maruri, 2010), severe mental health issues (Insel, 2008), and suicide (The Howard League for Penal Reform, 2016) outweigh the relative affordability of hormone therapy.

To reduce interpersonal-level barriers associated with custody staff bias, interventions might include transgender-specific cultural and clinical competency trainings. Presentations, written materials, and webinars are common methods of continuing education training for non-correctional healthcare staff shown to increase knowledge about unfamiliar clinical and cultural content (Hanssmann et al., 2008; Matza et al., 2015). Trainings specifically adapted to transgender health have the potential to decrease bias and increase provider knowledge regarding transgender health complexities. Preliminary evidence from an evaluation of a transgender health training with correctional healthcare providers in New England indicates significant increases in transgender-related cultural and clinical competence following this training, which was specifically adapted to the correctional environment (White Hughto et al., in press-b; White Hughto and Clark, in press). Given the early success of these interventions, future trainings should be adapted to improve the cultural competence of custody staff – a population that this study shows is highly in need of education in this area.

4.5. Limitations

These findings are limited by the qualitative nature of the study (e.g., potential social desirability bias); however, an attempt to attenuate social desirability bias was made through use of phone interviews that were not audio recorded. Further, this was a convenience sample that was susceptible to self-selection bias. Participants were recruited from one state in New England; thus, findings may not be transferable to correctional healthcare providers in other regions of the U.S. Further, a vast majority of the sample (90%) was female. Prior research finds that heterosexual women are less hostile towards LGBT people than heterosexual men (Herek, 1988): future research might consider stratifying by correctional healthcare provider gender to determine whether gender-related differences in provision of care to transgender inmates exist.

5. Conclusion

This study represents the first investigation of structural, interpersonal, and individual barriers to providing transgender-affirming healthcare from the perspective of correctional healthcare providers. Correctional healthcare providers report that transgender individuals do not receive adequate, gender-affirming healthcare while incarcerated. Study interviews evidenced bias and discrimination from custody staff and healthcare providers, refusal of gender-related care, and withholding of medication. Transgender-specific healthcare policy changes and training implementation for both correctional healthcare providers and custody staff are needed to increase access to gender-affirming medical care, help reduce bias and misinformation about transgender inmates' needs, and positively impact the health and wellbeing of this disproportionately affected segment of the U.S. and global prison system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their time as well as the correctional administrators who supported the study and facilitated participant recruitment. This study was funded with the support of the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (Clara Mayo Research Grant, 2015). Kirsty Clark is supported by the Graduate Division, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health (Fellowship in Epidemiology, #104733842). Jaclyn White Hughto is supported by the National Institutes of Minority Health Disparities (1F31MD011203-01).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.052.

References

- Al-Yateem N. The effect of interview recording on quality of data obtained: a methodological reflection. Nurse Res. 2012;19:31–35. doi: 10.7748/nr2012.07.19.4.31.c9222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and StatisticalManual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, Williams BA, Murray OJ. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166:103–109. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassichis D, Spade D. It's War in Here: a Report on the Treatment of Transgender and Intersex People in New York State Men's Prisons. Sylvia Rivera Law Project; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bonczar TP. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the US Population, 1974–2001. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:1820–1829. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GR. Autocastration and autopenectomy as surgical self-treatment in incarcerated persons with gender identity disorder. Int. J. Transgenderism. 2010;12:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GR. Qualitative analysis of transgender inmates' correspondence implications for departments of correction. J. Correct. Health Care. 2014;20:334–342. doi: 10.1177/1078345814541533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GR, McDuffie E. Health care policies addressing transgender inmates in prison systems in the United States. J. Correct. Health Care. 2009;15:280–291. doi: 10.1177/1078345809340423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh T, Hopwood R, Lambert C. Informed consent in the medical care of transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. AMA. J. Ethics. 2016;18:1147. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.11.sect1-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, Katz M. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. Am. J. Public Health. 2001;91:915. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int. J. Transgenderism. 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Transsexual patients' psychiatric comorbidity and positive effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on mental health: results from a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Reports. Evaluating Prescription Drugs Used to Treat the Symptoms of Menopause. Consumer Reports Best Buy Drugs. Consumers Union 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose. SocioCultural Research Consultants. LLC; Los Angeles, CA: 2016. Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. [Google Scholar]

- Edney R. To keep me safe from harm-transgender prisoners and the experience of imprisonment. Deakin. l. Rev. 2004;9:327. [Google Scholar]

- Emmer P, Lowe A, Marshall R. Hearts on a Wire Collective. Philadelphia, PA: 2011. This Is a Prison, Glitter Is Not Allowed: Experiences of Trans and Gender Variant People in Pennsylvania's Prison Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JB, Kisler KA, Reback CJ. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors among transgender women in Los Angeles. Archives Sex. Behav. 2014;43:1651–1661. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0368-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J. Urban Health. 2001;78:214–235. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaze LE, Kaeble D. Correctional Populations in the United States. Vol. 2013. Bureau of Justice Statistics (U.S. Department of Justice: U.S. Department of Justice); 2011. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Mottet L, Tanis JE, Harrison J, Herman J, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: a Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey: National Center for Transgender Equality 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Roberts C, Kennedy S. Health-related issues in prisoner reentry. Crime Delinq. 2001;47:390–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hanssmann C, Morrison D, Russian E. Talking, gawking, or getting it done: provider trainings to increase cultural and clinical competence for transgender and gender-nonconforming patients and clients. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy. 2008;5:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DC, Kleffel D, Fisher AA. Prisoners' perspectives of health problems and healthcare in a US women's jail. Women & Health. 2006;44:119–136. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Heterosexuals' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: correlates and gender differences. J. Sex Res. 1988;25:451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman LF. Human saliva as a diagnostic specimen. J. Nutr. 2001;131:1621S–1625S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1621S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Assessing the economic costs of serious mental illness. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 2008;165(6):663–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness V, Maxson CL, Matsuda KN, Sumner JM. Violence in California correctional facilities: an empirical examination of sexual assault. Bulletin. 2007;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon J, Carrington K, Low H, Miller R, Yazdy M. Coming Out of Concrete Closets: a Report on Black and Pink's LGBTQ Prisoner' Survey. Black and Pink; Boston, MA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maruri S. Hormone therapy for inmates: a metonym for transgender rights. Cornell JL Pub. Pol'y. 2010;20:807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matza AR, Sloan CA, Kauth MR. Quality LGBT health education: a review of key reports and webinars. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2015;22:127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, Fleming MZ. Transgender and gender variant populations with mental illness: implications for clinical care. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2011;42:208. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal K, Vargas V, Meterko V, Hamit S, McLean K, Paludi M. Transgender female sex workers: personal perspectives, gender identity development, and psychological processes. Manag. Divers. today's workplace Strategies employees employers. 2012;1:123–153. [Google Scholar]

- Okamura A. Equality behind bars: improving the legal protections of transgender inmates in the California prison systems. Hastings Race Poverty LJ. 2011;8:109. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson EJ. The dose–response of time served in prison on mortality: New York State, 1989–2003. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:523–528. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J, Harris F, Condon L, Kemple T. Nursing care of prisoners: staff views and experiences. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010;66:1257–1265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reback CJ, Fletcher JB. HIV prevalence, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors among transgender women recruited through outreach. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1359–1367. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0657-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Biello KB, Hughto JMW, Kuhns L, Mayer KH, Garofalo R, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and comorbidities in a diverse, multicity cohort of young transgender women: baseline findings from project lifeskills. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:481–486. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Bradford J, Hopwood R, Gonzalez A, Makadon H, Todisco D, et al. Comprehensive transgender healthcare: the gender affirming clinical and public health model of Fenway health. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2015;92:584. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9947-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, White JM, Bradford JB, Mimiaga MJ. Transgender health disparities: comparing full cohort and nested matched-pair study designs in a community health center. LGBT Health. 2014;1:177–184. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum D. Trapped in Sing Sing: transgendered prisoners caught in the gender binarism. Mich. J. Gend. L. 1999;6:499–571. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi NK, Bauer GR, Scanlon K, Kaay M, Travers R, Travers A. Non-prescribed hormone use and self-performed surgeries: do-it-yourself transitions in transgender communities in Ontario, Canada. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:1830–1836. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routh D, Abess G, Makin D, Stohr MK, Hemmens C, Yoo J. Transgender inmates in prisons a review of applicable statutes and policies. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2015:1–22. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15603745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:713–719. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.132035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelius J, Jenness V. Challenges and opportunities for gender-affirming healthcare for transgender women in prison. Int. J. Prison. Health. 2017;13:32–40. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-08-2016-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short V, Cooper J, Shaw J, Kenning C, Abel K, Chew-Graham C. Custody vs care: attitudes of prison staff to self-harm in women prisoners–a qualitative study. J. Forensic Psychiatry & Psychol. 2009;20:408–426. [Google Scholar]

- Stotzer RL. Violence against transgender people: a review of United States data. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009;14:170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994;17:273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner J, Sexton L. Lost in translation: looking for transgender identity in women's prisons and locating aggressors in prisoner culture. Crit. Criminol. 2015;23:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- The Howard League for Penal Reform. The Cost of Prison Suicide. London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Pew Charitable Trusts. Managing Prison Health Care Spending. Mac-Arthur Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. California funds 1st US inmate sex reassignment. New York Times; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNODC, U.N.O.o.D.a.C. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (The Nelson Mandela Rules) Government of Germany; United Nations: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Clark KA. Designing a transgender health training for correctional healthcare providers: a feasibility study. Prison J. doi: 10.1177/0032885519837237. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Clark K, Altice FL, Reisner SL, Kershaw TS, Pachankis JE. Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: a qualitative study of transgender women’s healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. Int. J. Prison. Health. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-02-2017-0011. (in press-a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Clark K, Altice FL, Reisner SL, Kershaw TS, Pachankis JE. Improving correctional healthcare providers' ability to care for transgender patients: development and evaluation of a theory-driven cultural and clinical competence intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.004. (in press-b) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL. A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgender Health. 2016;1:21–31. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2015.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015;147:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmott Y. Prison nursing: the tension between custody and care. Br. J. Nurs. 1997;6:333–336. doi: 10.12968/bjon.1997.6.6.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E, Garofalo R, Harris RD, Herrick A, Martinez M, Martinez J, et al. Transgender female youth and sex work: HIV risk and a comparison of life factors related to engagement in sex work. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:902–913. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9508-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M-F, Manning D, van den Berg JJ, Operario D. Stigmatization and mental health in a diverse sample of transgender women. LGBT Health. 2015;2:306–312. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.