Abstract

Objectives

Rugby has a high injury incidence and therefore BokSmart introduced the Safe Six injury prevention programme in 2014 in an attempt to decrease this incidence. In 2015, BokSmart used a ‘targeted marketing approach’ to increase the awareness and knowledge of the Safe Six. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the change in the knowledge of coaches and players of the Safe Six programme, compared with the launch year, following a ‘targeted marketing approach’.

Design

Ecological cross-sectional questionnaire study

Setting

The 2014–2016 South African rugby union youth week tournaments.

Participants

Questionnaires were completed by 4502 players and coaches who attended any of the four youth week tournaments during 2014–2016.

Outcome measures

Logistic regression (adjusted OR, 95% CI) was performed in comparison to year prior to targeted marketing, separately for coaches and players, for changes in awareness and knowledge.

Results

The awareness of the Safe Six increased significantly for players in 2015 (1.74 times (95% CI 1.49 to 2.04)) and in 2016 (1.54 times (95% CI 1.29 to 1.84)). Similarly for coaches, there was a 3.55 times (95% CI 1.23 to 9.99) increase in 2015 and a 10.11 times (95% CI 2.43 to 42.08) increase in 2016 compared with 2014. Furthermore, a player was significantly more likely to be aware of the Safe Six if his coach was aware of the programme (p<0.05).

Conclusions

The knowledge and awareness of the BokSmart Safe Six of both players and coaches increased in 2015 and 2016 (compared with 2014) since the launch of the programme. Coaches, the Unions/the South African Rugby Union and social media were the largest contributors to knowledge in coaches and players. While the ‘targeted marketing approach’ was associated with an increase in awareness, future studies should determine if this translates into behavioural change.

Keywords: injury prevention, awareness, cross-sectional, social media

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is novel as it looks at what sources South African coaches and players received their BokSmart injury prevention information from.

The findings could help BokSmart and other nationwide injury prevention programmes target audiences more effectively.

The number of repeat participants completing the survey in consecutive years is unknown and assumed to be minimal.

The results are self-reported and not observed behaviour and should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

Rugby union (hence referred to as ‘rugby’) is a sport played globally and has a high risk of injury when compared with other sports.1–3 Owing to this high risk, multiple nationwide injury prevention programmes have been designed and implemented in various countries, such as RugbySmart in New Zealand and Smart Rugby in Australia.4 5 In South Africa, the South African Rugby Union (SARU) developed and implemented BokSmart in an attempt to decrease the injury burden through research-based initiatives.6

The BokSmart injury prevention programme focuses its initiatives through mandatory biennial courses, which are DVD-facilitated workshops for all coaches and referees in South Africa.7 RugbySmart also targets the coaches and referees, and has been associated with decreases in spinal cord injuries and overall injury rates in specifically targeted areas.8 9 There was also an increase in ‘safe’ behaviours in the contact situations following the introduction of RugbySmart.8 Similarly, the BokSmart programme has also been associated with improvements in injury prevention behaviours in players, which is hypothesised to lead to a decrease in injuries.10 11 Furthermore, BokSmart has been associated with a decrease in catastrophic injuries in junior rugby players in South Africa.12 These studies all indicate that the coach-targeted approach for injury prevention in rugby is successful.11 These studies were all quantitative and descriptive studies, which provide information regarding changes over time in injury rates, knowledge and awareness of the programme and allow for inferences to be made.

Following the success of the BokSmart programme, BokSmart further developed and implemented the Safe Six exercise-based injury prevention programme in the beginning of 2014 (http://boksmart.sarugby.co.za/content/safe-six). The BokSmart Safe Six programme is coach-targeted, and aimed at being implemented as a warm-up before training or competition.13 The Safe Six was developed using clinical knowledge and research to address the most commonly occurring injuries in rugby union, and was designed to be implemented by rugby players of all ages. Following the introduction in 2014, no explicit marketing was performed (deemed the ‘pre’marketing period). Subsequently in 2015, prior to the annual SARU youth week tournaments, a ‘targeted marketing approach’ was taken using emails to the respective youth week teams’ coaches, provincial unions and SARU. As with all BokSmart programmes, while the Safe Six is coach-targeted, it is hypothesised that there will be knowledge transfer from the coaches to the players.

This study had three aims. First, to determine the change in the knowledge of coaches and players of the Safe Six programme, compared with the launch year, following a targeted marketing approach. Second, to evaluate whether a coach-targeted intervention approach is associated with player knowledge and awareness of the Safe Six programme. Finally, to explore the reasons why coaches and players use the Safe Six programme.

Methods

Participants

The players and coaches of all South African teams attending the SARU youth week tournaments in 2014, 2015 and 2016 were invited to complete a questionnaire (not the same players every year, but all players at all tournaments every year). The youth week tournaments are an annual opportunity to showcase the talent of the best youth rugby players in South Africa’s various provincial unions. The youth week tournaments included in this study were the Under 13 Craven Week, U16 Grant Khomo Week, Under 18 Academy Week, Under 18 Craven Week, Under 18 Learners with Special Education Needs Week and Under 17 Sevens Tournament. The players and coaches were asked to complete the questionnaire independently at any point during the tournament and to return it to the tournament medical officer. Hard copies of the questionnaire were distributed to the players and coaches and their handwritten responses were transferred into Excel for data entry and then into SPSS for statistical analysis. Each coach, parent of a player under the age of 18 and player gave written consent prior to the tournament to be involved in the study.

BokSmart Safe Six targeted marketing

In 2014, BokSmart launched the Safe Six programme, but did not perform any explicit marketing; this is deemed the ‘pre’marketing period for the current study. In 2015, before the youth week tournaments, a targeted marketing approach was taken, using emails (including the full Safe Six programme) to the respective youth week coaches, that is, provincial unions and SARU both provided informative material to all coaches attending the youth weeks. The social media accounts of SA Rugby Youth Weeks (10 172 Facebook and 1959 Twitter followers, 2017) and BokSmart (4060 Facebook and 2996 Twitter followers, 2017) were used as platforms to market the Safe Six programme, and so the 2015 year is the ‘during’ marketing period. The social media marketing included copies of the Safe Six posters (details regarding the exercises, repetitions and images) and links to YouTube instructional videos. This targeted marketing took place during the 10 weeks leading up to all the tournaments in 2015. In 2016, similarly to 2014, no specific marketing was made towards those attending the youth weeks and can be considered the ‘post’marketing period.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed by BokSmart to determine the players’ and coaches’ knowledge, behaviour and awareness of the Safe Six injury prevention programme. The BokSmart Safe Six is targeted at the coach and therefore the questionnaire (see online supplementary material 1) assesses knowledge (of the BokSmart Safe Six) and its transfer to behaviour (reported usage of the BokSmart Safe Six) of the coaches, as well as the barriers and facilitators in this process. The questionnaire also assesses the fidelity of knowledge by requiring the participants to correctly name the exercises included in the BokSmart Safe Six programme. Following this, the BokSmart coach-targeted approach would assume that this knowledge of the programme would transfer from the coach to the player, and therefore, the questionnaire also assesses the knowledge and behaviour of the players regarding the BokSmart Safe Six.

bmjopen-2017-018575supp001.pdf (454.8KB, pdf)

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were performed on the tournaments, the participants, their roles and their responses. Logistic regression was performed to determine an adjusted OR (aOR, with 95% CIs) (adjusting for team role and year) on various binary outcomes (yes or no). All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.23 (2015). Statistical significance was accepted when the p<0.05.

Results

Over the 3 years of data collection, a total of 4502 participants completed the questionnaire from six different tournaments in three consecutive years. Of the participants, 92% were players, and the rest were coaches or of unknown role (table 1).

Table 1.

The team roles of participants who completed the questionnaire (n=4502)

| Team role | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total |

| Coach | 27 | 52 | 33 | 112 |

| Player | 1351 | 1715 | 1070 | 4136 |

| Unknown | 136 | 80 | 38 | 254 |

| Total | 1514 | 1847 | 1141 | 4502 |

For players, the awareness of the Safe Six increased significantly in 2015 (1.74 times (95% CI 1.49 to 2.04)) and in 2016 (1.54 times (95% CI 1.29 to 1.84)) compared with 2014 (table 2). Similarly, for coaches, there was a 3.55 times (95% CI 1.23 to 9.99) increase in 2015 and a 10.11 times (95% CI 2.43 to 42.08) increase in 2016 compared with 2014. However, the difference between 2015 and 2016 for both coaches and players was not significant.

Table 2.

Responses to the question “Have you ever heard of the BokSmart Safe Six?” (n=4050, unknown role=245, blank=207)

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | |||||

| Team role | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Coach, n (%) | 13 (52) | 12 (48) | 11 (23) | 36 (77) | 3 (10) | 28 (90) | 27 (26) | 76 (74) |

| Player, n (%) | 946 (73) | 341 (27) | 1002 (62) | 627 (38) | 663 (64) | 368 (36) | 2611 (66) | 1336 (34) |

| Total | 959 (73) | 353 (27) | 1013 (60) | 663 (40) | 666 (63) | 396 (37) | 2638 (65) | 1412 (35) |

Furthermore, in 2015 players were 4.94 (95% CI 2.78 to 8.80) times more likely to be aware of the Safe Six if their respective coaches were aware of the programme (table 3).

Table 3.

The players’ responses related to what their respective coaches answered to the question “Have you ever heard of the BokSmart Safe Six?” during 2015 (number of coaches=47)

| Coaches’ response | Players’ response % (n) | ||

| No | Yes | Total | |

| No | 20 (123) | 2 (11) | 22 (134) |

| Yes | 46 (278) | 32 (190) | 78 (468) |

| Total | 66 (401) | 34 (201) | 100 (602) |

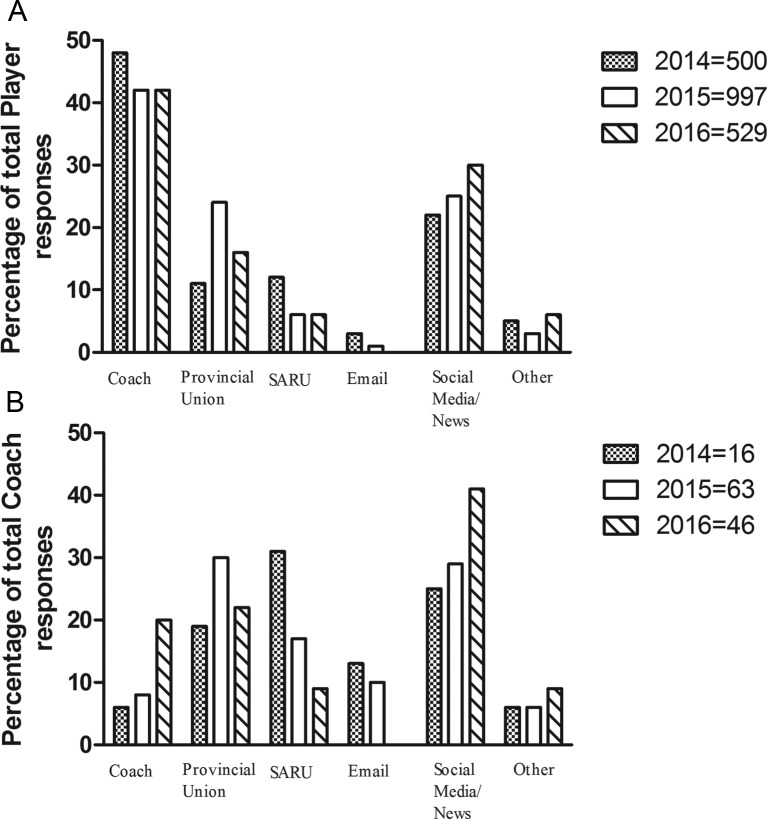

SARU (2014), provincial unions (2015) and social media/news (2016) were the largest sources of information of the Safe Six over the years for coaches (figure 1). For players, the largest source of information regarding the Safe Six was through coaches, social media/news was the second largest and the provincial unions were also large contributors to the dissemination of knowledge.

Figure 1.

(A) Players’ responses to the question “How did you come to hear about the BokSmart Safe Six?” (participants could choose multiple options). (B) Coaches’ responses to the question “How did you come to hear about the BokSmart Safe Six?” (participants could choose multiple options).

The overall finding was that the players had a poor ability to name the exercises. Multiple participants could name some of the six exercises, but not all of them, and different combinations of the exercises (table 4).

Table 4.

The number of correct answers when the participants were asked to list as many of the BokSmart Safe Six exercises as they could remember in 2015 only

| Exercise | Coach | Players | Total |

| Six metre shuttle run | 22 | 321 | 343 |

| Six-point lunge | 19 | 294 | 313 |

| Buttsmart six | 14 | 257 | 271 |

| Six-on-a-side push pp | 16 | 247 | 263 |

| Six bok lunge | 18 | 223 | 241 |

| Six dynamic reaches | 17 | 139 | 156 |

In 2015, the reported usage of the Safe Six exercises was significantly higher for players than that of 2014 (aOR=1.75 (95% CI 1.36 to 2.26)), but in 2016 there was no significant change compared with 2014 (table 5). For coaches, the usage was significantly higher in 2015, with a 4.14 times (95% CI 1.15 to 14.92) increase, however in 2016 there was no significant change when compared with 2014. If a participant had answered ‘no’ to ‘have they ever heard of the BokSmart Safe Six’, they were screened to not be included in this question, however if they left that question blank, they could be included.

Table 5.

Participants’ responses to the question “In the last 6–8 weeks, have you ever used the BokSmart Safe Six exercises?” (n=1599, blank=48)

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | |||||

| Team role | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Coach, n (%) | 8 (50) | 8 (50) | 7 (19) | 29 (81) | 6 (21) | 22 (79) | 21 (26) | 59 (74) |

| Player, n (%) | 146 (43) | 195 (57) | 224 (32) | 466 (68) | 233 (53) | 207 (47) | 603 (41) | 868 (59) |

| Total, n (%) | 154 (43) | 203 (57) | 231 (32) | 495 (68) | 239 (51) | 229 (49) | 624 (40) | 927 (60) |

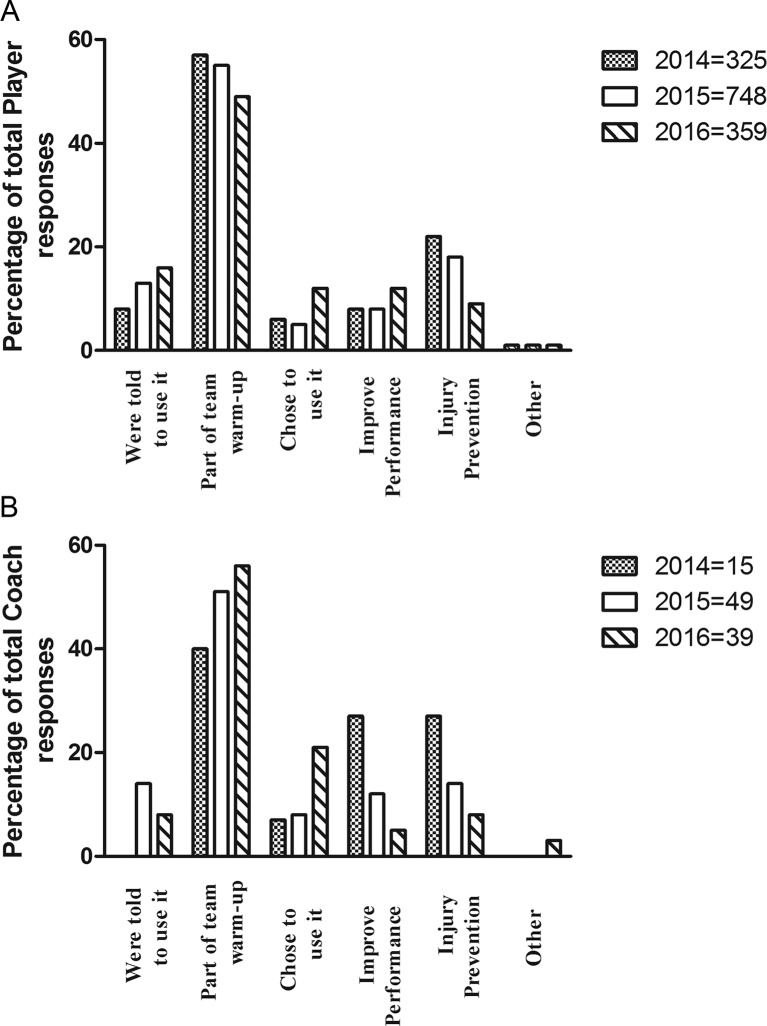

The largest number of participants reported using the Safe Six because it was ‘part of their team warm-up’ (over all the years) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Players’ who claimed to use the exercises, these are their responses to the question “Why did you use the BokSmart Safe Six exercises?” (participants could tick multiple options). (B) Coaches’ who claimed to use the exercises, these are their responses to the question “Why did you use the BokSmart Safe Six exercises?” (participants could tick multiple options).

Discussion

Overall, there were significant changes in the awareness and knowledge of the coaches’ and players’ of the BokSmart Safe Six injury prevention programme. Furthermore, there was a significant relationship between the knowledge and awareness of coaches and their respective players. This finding supports BokSmart’s coach-targeted approach.

Awareness of the Safe Six increased in 2015 and 2016 compared with 2014, in coaches and players following the targeted marketing period. The coaches’ knowledge and awareness of the Safe Six was significantly higher than that of the players’, which was to be expected because BokSmart as a whole and specifically the Safe Six is a coach-targeted programme.7 Furthermore, when comparing the coaches’ knowledge and awareness to their respective players’ knowledge and awareness, there was a significant relationship in the marketing year, indicating that the coach-driven approach was effective in knowledge transfer to the players. Furthermore, when considering the reported use of the exercises, in 2016 more than half of the players reported not using the exercises, whereas the majority of coaches reported that they did use the exercises. While the question might overestimate the implementation of the exercises, either the coaches are showing social desirability bias or the knowledge transfer from coach to player appears to have decreased. If it is the latter, at least the exercises are still being implemented. This relationship, and the consequences of this relationship has been illustrated in other studies in rugby. In New Zealand, RugbySmart is a coach-targeted programme, which has been associated with an increase in injury preventing behaviours in players.8 In South Africa, the BokSmart programme as a whole has also been associated with positive changes in injury prevention behaviours in the players.10 Other more specific exercise-based injury prevention programmes have also been coach-targeted, with their results indicating a preventive effect (in certain areas, not overall injuries) for the players.14 15 These programmes indicate that coach-targeted programmes have the desired effect on the players they are trying to reach.

However, when further analysing the fidelity of knowledge of the coaches and players of the Safe Six, their ability to name the exercises was poor, compared with the total number of participants. Therefore, if the Safe Six is a programme important to BokSmart, and is potentially effective in preventing injuries,13 it is suggested that BokSmart continues to perform the marketing measures on an annual basis (more than just incorporated into the current BokSmart biennial courses)7 to reach the target audiences and to increase the use of the programme.

As mentioned above, the Safe Six programme was designed as an injury prevention programme, but exploring the arguments as to why players and coaches implement the exercises is important to understand. The explanations for use of the Safe Six programme were predominantly for the warm-up in both the players and coaches, however, the second most popular explanation for players was injury prevention and for coaches was to improve performance. The programme was designed to be incorporated into the warm-up as an injury prevention programme, and therefore is being used as intended. However, there could also be a ‘misconception’ between coaches that the Safe Six is a performance enhancement programme, instead of an injury prevention programme. It must be noted that a significant number of both the coaches and players perceived the Safe Six to be easy to use (which was BokSmart’s goal when designing the programme), which therefore did not hamper their experiences regarding the programme.

The source of information varied between coaches and players. The coaches reported receiving most of their information from social media/news. Coaches received communication from their respective provincial unions who are governed by SARU, and therefore this relationship was expected. Social media/news were especially targeted in the marketing period using mostly the Twitter and Facebook BokSmart accounts (2996 and 4065 followers, respectively) (April 2017). For the players, most heard of the Safe Six from their coaches. The next popular source of hearing about the programme was from social media/news. This raises an interesting method of communicating for injury prevention awareness. The method was free and proved effective in reaching both the coaches and players. Social media and phone applications have become a new form of implementation for injury prevention programmes.16 17 In a review of phone-based injury prevention applications, there were 18 applications which claimed to have sports or health benefits.16 Such findings indicate a shift towards the technology-based form of injury prevention methods. While these applications may not all have been based on scientific principles, they still attract attention.

While technology-based reach can be high, full utilisation may be low. For example, an application focused on reducing ankle sprains had a low compliance once downloaded.17 Therefore targeted efforts are required to ensure that the programme is used appropriately.17 This principle could also be applied to the Safe Six where the reach and usage increased during the marketing period (possibly because of the social media exposure), and then decreased postmarketing. This is important knowledge for BokSmart and how they continue to disseminate knowledge regarding the Safe Six and future initiatives.

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional study with self-reported knowledge, usage and exposure. Therefore, the results must be interpreted in this context. Forty-four percent of players could not be linked to a coach to determine the player/coach knowledge transfer, and this must be considered when interpreting those results. It must be noted that the percentage of repeat players completing the questionnaire in subsequent years is assumed to be minimal (as with all studies using the SARU youth week rugby tournaments as the cohort), however the coaches have never been assessed and there could be more repeat participants.18–22

Conclusion

The knowledge and awareness of the BokSmart Safe Six of both players and coaches increased in 2015 and 2016 (compared with 2014) since the launch of the programme, however, did slightly decrease during the postmarketing period. The coaches reported receiving their information regarding the Safe Six from the Unions/SARU and social media/news. The information for the players, came from the coaches and social media/news. Reported usage of the programme increased in 2015 (ie, the marketing period), but decreased to the premarketing levels in 2016. Finally, the reasons for using the programme were predominantly for the warm-up, injury prevention and for performance improvements. The information gathered in this study will help with designing targeted marketing for future programmes and for further promotion of the BokSmart Safe Six. It also provides insight into the perceptions of the coaches and players regarding the Safe Six and therefore allows for BokSmart to make adjustments accordingly.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NS was granted access to the data and was involved in conceptualising the manuscript; she also conducted statistical analyses and wrote the initial drafts of the manuscript. JB and EV were also involved in the statistical analyses. All authors (EV, ML, WvM and JB) were involved in conceptualising and editing drafts of the paper, in the order that they appear on the author list.

Funding: NS’s PhD is funded by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam/National Research Foundation South Africa through the Desmond Tutu Doctoral Scholarship, administered through the South Africa Vrije Universiteit Strategic Alliance (SAVUSA). NS also receives funding from the University of Cape Town, Zuid-Afrika Huis study foundation and the Oppenheimer Memorial Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study received ethical clearance from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town (HREC 108/2017).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are published, and therefore there is no additional data available. If raw data are requested, requests will be reviewed on a discretionary basis by BokSmart (who can be contacted via email through the corresponding author: swrnic009@myuct.ac.za).

References

- 1. Brooks JH, Kemp SP. Recent trends in rugby union injuries. Clin Sports Med 2008;27:51–73. 10.1016/j.csm.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train 2007;42:311–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams S, Trewartha G, Kemp S, et al. A meta-analysis of injuries in senior men’s professional rugby union. Sports Med 2013;43:1043–55. 10.1007/s40279-013-0078-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Union NZR. Key points for the tackler and ball-carrier, Australian Rugby Union SmartRugby: confidence in contact. A guide to the SmartRugby program, 2008:18–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Union NZR. Technique: the key factors in the tackle and taking the ball into contact. RugbySmart 2007: a guide to injury prevention for peak performance, 2007:12–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rugby S. BokSmart: safe and effective techniques in Rugby - practical guidelines. BokSmart, Cape Town, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viljoen W, Patricios J. BokSmart - implementing a National Rugby Safety Programme. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:692–3. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gianotti SM, Quarrie KL, Hume PA. Evaluation of RugbySmart: a rugby union community injury prevention programme. J Sci Med Sport 2009;12:371–5. 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quarrie KL, Gianotti SM, Hopkins WG, et al. Effect of nationwide injury prevention programme on serious spinal injuries in New Zealand rugby union: ecological study. BMJ 2007;334:1150 10.1136/bmj.39185.605914.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown JC, Gardner-Lubbe S, Lambert MI, et al. The BokSmart intervention programme is associated with improvements in injury prevention behaviours of rugby union players: an ecological cross-sectional study. Inj Prev 2015;21:173–8. 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown JC, Gardner-Lubbe S, Lambert MI, et al. Coach-directed education is associated with injury-prevention behaviour in players: an ecological cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med 2016. (Epub ahead of print: 25 Nov 2016). 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown JC, Verhagen E, Knol D, et al. The effectiveness of the nationwide BokSmart rugby injury prevention program on catastrophic injury rates. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016;26:221–5. 10.1111/sms.12414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sewry N, Verhagen E, Lambert M, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness and implementation of the BokSmart Safe Six Injury Prevention Programme: a study protocol. Inj Prev 2016. (Epub ahead of print: 2 Nov 2016). 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finch CF, Twomey DM, Fortington LV, et al. Preventing Australian football injuries with a targeted neuromuscular control exercise programme: comparative injury rates from a training intervention delivered in a clustered randomised controlled trial. Injury prev 2015;22:123–8. 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hislop M, Stokes K, Williams S, et al. The efficacy of a movement control exercise programme to prevent injuries in youth rugby: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:330.3–1. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097372.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Mechelen DM, van Mechelen W, Verhagen EA. Sports injury prevention in your pocket?! Prevention apps assessed against the available scientific evidence: a review. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:878–82. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vriend I, Coehoorn I, Verhagen E. Implementation of an app-based neuromuscular training programme to prevent ankle sprains: a process evaluation using the RE-AIM Framework. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:484–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown J, Verhagen E, Viljoen W, et al. The incidence and severity of injuries at the 2011 South African Rugby Union (SARU) Youth Week tournaments. South Afr J Sports Med 2012:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burger N, Lambert MI, Viljoen W, et al. Mechanisms and factors associated with tackle-related injuries in South African Youth Rugby Union players. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:278–85. 10.1177/0363546516677548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burger N, Lambert MI, Viljoen W, et al. Tackle-related injury rates and nature of injuries in South African Youth Week tournament rugby union players (under-13 to under-18): an observational cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005556 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burger N, Lambert MI, Viljoen W, et al. Tackle technique and tackle-related injuries in high-level South African Rugby Union under-18 players: real-match video analysis. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:932–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mc Fie S, Brown J, Hendricks S, et al. Incidence and factors associated with concussion injuries at the 2011 to 2014 South African Rugby Union Youth Week Tournaments. Clin J Sport Med 2016;26:398–404. 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018575supp001.pdf (454.8KB, pdf)