Abstract

Objectives

To investigate factors influencing the effectiveness of intensive sound masking therapy on tinnitus using logistic regression analysis.

Design

The study used a retrospective cross-section analysis.

Participants

102 patients with tinnitus were recruited at the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, China.

Intervention

Intensive sound masking therapy was used as an intervention approach for patients with tinnitus.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Participants underwent audiological investigations and tinnitus pitch and loudness matching measurements, followed by intensive sound masking therapy. The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) was used as the outcome measure pre and post treatment. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to investigate the association of demographic and audiological factors with effective therapy.

Results

According to the THI score changes pre and post sound masking intervention, 51 participants were categorised into an effective group, the remaining 51 participants were placed in a non-effective group. Those in the effective group were significantly younger than those in the non-effective group (P=0.012). Significantly more participants had flat audiogram configurations in the effective group (P=0.04). Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that age (OR=0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.99, P=0.007), audiometric configuration (P=0.027) and THI score pre treatment (OR=1.04, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.07, P<0.001) were significantly associated with therapeutic effectiveness. Further analysis showed that patients with flat audiometric configurations were 5.45 times more likely to respond to intervention than those with high-frequency steeply sloping audiograms (OR=5.45, 95% CI 1.67 to 17.86, P=0.005).

Conclusion

Audiometric configuration, age and THI scores appear to be predictive of the effectiveness of sound masking treatment. Gender, tinnitus characteristics and hearing threshold measures do not seem to be related to treatment effectiveness. A further randomised control study is needed to provide evidence of the effectiveness of prognostic factors in tinnitus interventions.

Keywords: sound masking, tinnitus, audiometric configuration, prognostic factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A relatively large sample of participants were included in the present study.

A robust analytical method (ie, logistic regression) was employed to explore the predictive factors associated with significant effective outcomes of sound masking treatment.

Due to patient adherence in the context of Chinese culture and the healthcare system, only intensive sound masking intervention was provided, and the short-term effectiveness was subsequently assessed in the present study.

Introduction

Tinnitus is the perception of noise in the absence of any external sound. It is considered one of the most common and disturbing health problems.1 It is widely accepted that tinnitus is a symptom caused by diverse pathologies as a result of not only peripheral hearing loss, but also aberrant neural activity in the central auditory nervous system.2–4 Various theories have been proposed to elaborate underlying possible mechanisms, such as discordant theory—the discordant dysfunction of damaged outer hair cells and intact inner hair cells,5 and auditory plasticity theory—damaged cochlea activates auditory plasticity by enhancing neural activity in the central auditory pathway, which results in abnormal input to the central auditory system.4

Epidemiological studies indicate that one third of all adults experience tinnitus at some time in their lives and 10–15% have prolonged tinnitus requiring medical intervention.6 A number of interventions are available for tinnitus management within ENT/Audiology clinics, including pharmacotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), habituation therapy (tinnitus retraining therapy, TRT), electrical suppression (eg, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, r-TMS) and sound therapy (eg, sound masking). Of these, tinnitus sound masking therapy has been widely used in patients reporting any tinnitus characteristics.7 According to the Cochrane review by Hobson et al,8 9 no significant difference was shown in the loudness of tinnitus or the overall severity of tinnitus following the use of sound masking therapy when compared with other interventions.

Furthermore, evidence has shown that no single treatment for tinnitus is found effective in all patients.8 These discrepancies in effectiveness are largely due to the complex mechanisms behind the symptoms as indicated above and the severity of impact on sufferers. Previous studies suggest that there are many influencing factors, such as age, tinnitus characteristics, hearing status and demographic factors, which affect the effectiveness of tinnitus management.1 10 However, the results appear inconsistent. For example, Koizumi et al11 found better outcomes with TRT for patients with higher levels of tinnitus loudness, while Ariizumi et al12 reported lower tinnitus loudness to be predictive of better outcomes with TRT. In addition, Kleinjung et al6 suggest that mild hearing loss and shorter tinnitus duration are more likely to be beneficial when using rTMS. These results are in keeping with the influencing factors seen when using sound masking therapy.1 It is also noteworthy that younger age and severe depression contributed to a positive response with CBT.13 Conrad et al14 further clarify that dysfunctional cognition is associated with CBT outcome, that is, more severe dysfunctional cognition results in a more negative emotional outcome after CBT intervention.

To our best knowledge, there are few studies available on the factors that influence the effectiveness of sound masking therapy. A recent study by Theodoroff et al1 appears to be the only report directly investigating the factors associated with effective tinnitus treatment using sound masking therapy.1 Although they found several positive predictors, such as younger age, better self-reported hearing difficulty, shorter durations of tinnitus and better hearing threshold at low frequency region, these results were obtained by combining tinnitus treatment data from sound masking therapy or TRT. The separate analysis showed that younger participants had significant improvement only in the TRT group (P<0.017) and that age was not a significant factor in the group using sound masking therapy (P=0.143). Such bias indicated that further investigation is needed to clarify possible factors associated with effective sound masking therapy.

Evidence has shown that audiometric configuration is associated with ear pathologies. For example, noise-induced hearing loss is related to the audiogram with a 3–6 kHz dip.15 Understanding audiometric configurations may provide insights into the etiologic mechanism and prevalence of tinnitus.16–19 In the study by Demeester et al,19 tinnitus was found to be significantly more prevalent in individuals with a high-frequency steeply sloping audiogram than those with a flat audiogram. However, it is still unclear as to how audiometric configuration affects sound masking intervention in tinnitus.

The purpose of this study was to use logistic regression analysis to identify any factors that might influence tinnitus sound masking, and which might predict the effectiveness of sound masking interventions in tinnitus sufferers. Significant results would be valuable to practice in predicting the effectiveness of sound masking intervention and thus influence therapeutic strategy selection.

Materials and methods

Participants

The present research was a retrospective study of 102 patients with tinnitus who underwent audiological investigations and specific tinnitus examinations, followed by 7 days of sound masking intervention at the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, China. Detailed selection criteria for inclusion in this sudy were:-

They had sought clinical help for their tinnitus problem, which had lasted more than 2 weeks.

They had no history of head trauma or central nervous system disorders.

They had mild to severe sensorineural hearing loss. All patients with tinnitus with either current conductive hearing loss or previous middle ear surgery (eg, mastoidectomy) were excluded.17

Patients with pulsatile tinnitus due to aberrant vascular malformation were also excluded.

The mean age was 44.98 years (SD 15.41). There were 46 men and 56 women (table 1). This study was approved by the ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and audiological characteristics between the effective and non-effective groups in patients with tinnitus who received the sound masking intervention

| Variable | Total (n=102) |

Effective group (n=51) |

Non-effective group (n=51) |

χ2/t test | P value |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 44.98±15.41 | 41.20±15.41 | 48.76±14.58 | −2.55 | 0.012* |

| Gender (n, %) | 2.53 | 0.163 | |||

| Male | 46 (45.1%) | 19 (37.3%) | 27 (52.9%) | ||

| Female | 56 (54.9%) | 32 (62.7%) | 24 (47.1%) | ||

| Hearing status | |||||

| Hearing threshold in tinnitus ears (dB HL) | 53.75±27.66 | 52.51±26.94 | 54.98±28.57 | −0.45 | 0.65 |

| Audiogram configurations (n, %) | 8.30 | 0.04* | |||

| Flat | 50 (49.02%) | 32 (62.75%) | 18 (35.29%) | ||

| HFGS | 21 (20.59%) | 9 (17.65%) | 12 (23.53%) | ||

| HFSS | 24 (23.63%) | 8 (15.69%) | 16 (31.37%) | ||

| Others | 7 (6.76%) | 2 (3.91%) | 5 (9.81%) | ||

| Tinnitus characteristics | |||||

| Laterality (n, %) | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Left | 54 (52.94%) | 27 (52.94%) | 27 (52.94%) | ||

| Right | 36 (35.29%) | 18 (35.29%) | 18 (35.29%) | ||

| Binaural | 12 (11.77%) | 6 (11.77%) | 6 (11.77%) | ||

| Duration (n, %) | 0.82 | 0.66 | |||

| Acute (<1 month) | 68 (66.66%) | 32 (62.75%) | 36 (70.59%) | ||

| Subacute (1–3 months) | 17 (16.67%) | 10 (19.61%) | 7 (13.73%) | ||

| Chronic (>3 months) | 17 (16.67%) | 9 (17.64%) | 8 (15.68%) | ||

| Tinnitus pitch (n, %) | 4.29 | 0.12 | |||

| Low (250–1000) Hz | 17 (16.67%) | 6 (11.76%) | 11 (21.57%) | ||

| Mid (1000–4000) Hz | 24 (23.53%) | 16 (31.37%) | 8 (15.69%) | ||

| High (4000–8000) Hz | 61 (59.80%) | 29 (56.87%) | 32 (62.74%) | ||

| Tinnitus loudness (dB) | 61.23±23.42 | 61.10±24.71 | 61.35±22.30 | −0.06 | 0.96 |

| Outcome measurement | |||||

| Pre-treatment THI | 45.80±21.76 | 54.04±18.45 | 37.57±21.86 | 4.11 | <0.001* |

| Post- treatment THI | 35.76±19.94 | 34.94±17.39 | 36.59±22.35 | −0.42 | 0.679 |

| THI change | 10.04±11.64 | 19.10±9.69 | 0.98±3.54 | 12.54 | <0.001* |

* There was a significant difference at p<0.05.

HFGS, high-frequency gently sloping; HFSS, high-frequency steeply sloping; THI, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.

Routine audiological examinations

Routine audiological examination consisted of otoscopy, followed by pure-tone audiometry in which air conduction thresholds were measured for both ears at 125 Hz, 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1.0 kHz, 2.0 kHz, 4.0 kHz and 8.0 kHz, and bone conduction hearing thresholds were measured between 250 Hz and 4.0 kHz in a sound-proof booth. The mean hearing threshold is the average of hearing sensitivity at the frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz.

On the basis of the audiograms, the audiometric configurations were classified as flat, high-frequency gently sloping (HFGS), high-frequency steeply sloping (HFSS), low-frequency ascending (LFA), mid-frequency U-curve (MFU) and mid-frequency reversed U-curve (MFRU) in accordance with the criteria used in the study by Hannula et al.15

Tinnitus specific assessments

Patients were asked to describe their tinnitus characteristics, including duration and laterality (ie, being in the right, left or both ears or central in the head). Tinnitus pitch and loudness matching measurements were performed ipsilaterally to the ear with predominant or louder tinnitus if there was a difference between the two sides. However, if the tinnitus ear had severe hearing loss, the contralateral ear was tested instead.20 When the tinnitus was equally loud on both sides or was localised in the head, the matching tones were given to the ear with the better hearing. Otherwise, the ear was chosen randomly if there was no difference between the acuity of the two ears.

During the tinnitus pitch matching tests, the nine audiometric frequencies between 125 Hz and 8.0 kHz (ie, 125 Hz, 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1.0 kHz, 2.0 kHz, 3.0 kHz, 4.0 kHz, 6.0 kHz and 8.0 kHz) were first used to roughly match the tinnitus pitch. Participants were initially asked to make a clear distinction between the tinnitus pitch perception and presented matching tones, and then they reported verbally whether the matching tone needed to go higher or lower until the exact matching tone or a close approximation to their tinnitus was obtained. The test tone was adjusted in a half-octave step. If there was no matching with a pure tone perceived by participants, narrow-band noise was used instead.

When the matching frequency was found, the level was initially set to 5 dB above the measured audiometric threshold to find an approximate tinnitus loudness level, then the level was adjusted in 1 dB steps until the subject indicated that the tone matched the loudness of their tinnitus.20

The sound masking intervention

Due to patient adherence in the context of Chinese culture and the healthcare system, a high drop-out rate occurred when patients received a longer duration of sound masking intervention. Considering the nature (ie, a retrospective study) and main purpose of the present study, current data were obtained only from intensive sound masking intervention, and the short-term effectiveness was assessed. The narrow-band noise at 10 dB above the tinnitus frequency was delivered to mask the tinnitus through headphones (Beyerdynamic DT880 pro), four to six times daily for 20–30 min, for a week.21 22

Self-reported tinnitus issues and Tinnitus Handicap Inventory questionnaire

Information on the tinnitus characteristics was collected. Patients were asked to describe the tinnitus duration and laterality (ie, in the right, left or both ears). According to the tinnitus sound masking therapy protocol, the effectiveness of the sound masking intervention was evaluated using the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) pre and post intervention. The THI questionnaire was provided to the patient before initial treatment, and after 7 days of sound masking therapy at tinnitus review clinics. The THI is a 25-item measure for evaluating the self-perceived level of handicap caused by tinnitus, based on a 0–100 increasing handicap scale (with 100 being total handicap and 0 being no handicap).23 Significant effectiveness was defined as a minimum improvement of seven points in overall THI score after the sound masking intervention.24 25

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as mean±SD or median (IQR), as appropriate, and categorical data are shown as frequencies and percentages. Student’s t tests (for continuous variables), Wilcoxon rank sum tests (for skewed distribution of continuous variables), and χ2 tests (for categorical variables) were used to assess differences in socio-demographic characteristics and tinnitus relevant factors by therapeutic efficacy (effectiveness vs non-effectiveness). Multivariate logistic regression models were performed to assess the independent association of demographic and tinnitus relevant factors with effective therapy. OR and its 95% CI were estimated for each factor. A P value<0.05 (two sided) was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

On the basis of the THI score changes pre and post sound masking intervention (ie, at least seven points), 51 participants were entered in the effective group, whereas the remaining 51 participants were placed in the non-effective group. table 1 shows comparisons of related factors between effective and ineffective groups, respectively. In the present study, age and gender factors were compared between the effective group and the non-effective group using Student’s t test and χ2 test, respectively. Student t test showed that participants in the effective group were significantly younger than those in the non-effective group (t=−2.55, P=0.012). However, there was no significant difference in gender between these two groups (χ2=2.53, df=1, P=0.163).

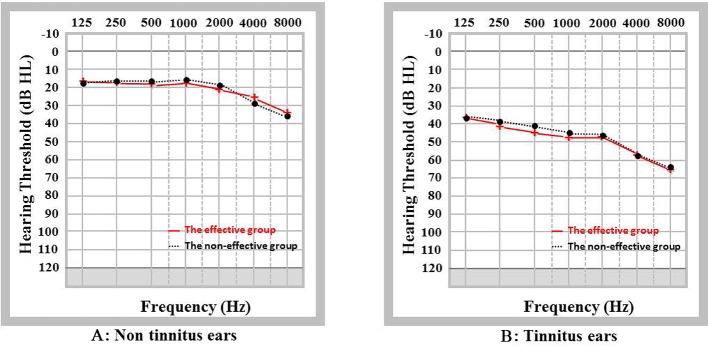

For the purpose of understanding the basic hearing status, the average pure tone hearing thresholds across frequencies from 125 Hz to 8000 Hz on tinnitus ears and non-tinnitus ears were analysed in both groups. As shown in figure 1, the hearing threshold of each frequency from 125 Hz to 8000 Hz revealed no significant differences between the two groups (P>0.05). Significantly worse hearing thresholds at each frequency in tinnitus ears were found in both groups (P<0.05) compared with hearing thresholds in non-tinnitus ears.

Figure 1.

(Colour online) The average pure tone hearing thresholds on tinnitus ears and non-tinnitus ears in effective and non-effective groups.

Based on audiometric configuration classification criteria, patients in the effective group had a flat audiogram (62.75%), HFGS (17.65%) and HFSS (15.69%). Patients in the non-effective group had a flat audiogram (35.29%), HFGS (23.53%) and HFSS (31.37%) configurations, respectively. Only seven cases had LFA, MFU or MFRU, which were classified as ‘others’ for the purpose of analysis. Further comparative analysis indicated that there were significantly more flat audiogram configurations together with lower HFGS and HFSS audiograms in the effective group than in the non-effective group (χ2=8.30, df=3; P=0.04) (table 1). Laterality, duration, tinnitus pitch and loudness showed no significant differences between the two groups.

As shown in table 1, the THI score for pre sound masking intervention was used as a baseline measurement. The average THI scores pre intervention were 54.04 (SD=18.45) and 37.57 (SD=21.86) for the effective and non-effective groups, respectively. Significantly lower THI scores were found pre intervention in the non-effective group (t=4.11, P<0.001). However, there was no significant difference in the THI scores post intervention between the two groups. As a result, significant differences were found in the pre and post THI score changes between the groups as a result of the intervention (19.10 vs 0.98, t=12.54, P<0.001). Further analysis showed that THI scores were significantly reduced in the effective group (t=−14.07, P<0.001), whereas no significant reduction in the THI scores was found in the non-effective group in comparison to the THI score between pre and post sound masking (t=−1.98, P=0.054).

To identify predictive factors for the effectiveness of the sound masking intervention, all factors that showed significance between both effective and non-effective groups were used as variables for a logistic regression analysis. Because the audiometric configuration variable was categorised as four sub-groups, estimates of pair comparisons were subsequently performed. Results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis are summarised in table 2. Age factor was negatively associated with effective treatment (OR=0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.99, P=0.007), indicating that an increase in age of 1 year is associated with a 4% decrease in the effectiveness of the intervention. The audiometric configuration factor was also found to be an independent factor associated with intervention effectiveness (P=0.027). Further analysis showed that patients with tinnitus with a flat audiometric configuration were 5.45 times more likely to have a successful intervention compared with those with HFSS configurations (OR=5.45, 95% CI 1.67 to 17.86, P=0.005). However, no significant results were found when comparing the other audiometric configurations. In addition, THI score pre treatment was positively associated with successful treatment (OR=1.04, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.07, P<0.001), indicating that one unit increase in THI score before treatment was associated with a 4% increase in therapeutic effectiveness.

Table 2.

Association of socio-demographic factors and audiogram configurations with effective therapy: multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Variables | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Age (years) | −0.04 | 0.17 | 7.34 | 0.007* | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.99 |

| Audiogram configurations | 9.18 | 0.027* | |||||

| Flat | 1.70 | 0.61 | 7.85 | 0.005* | 5.45 | 1.67 | 17.86 |

| HFGS | 0.81 | 0.71 | 1.31 | 0.252 | 2.24 | 0.56 | 8.93 |

| HFSS | reference | 1.00 | |||||

| Others | 0.05 | 1.03 | <0.01 | 0.960 | 1.05 | 0.14 | 7.89 |

| Prior treatment THI | 0.04 | 0.01 | 12.58 | <0.001* | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.07 |

* There was a significant difference at p<0.05.

HFGS, high-frequency gently sloping; HFSS, high-frequency steeply sloping; THI, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that certain factors can be prognostic for the effectiveness of intensive sound masking therapy. Logistic regression analysis indicates that age, audiogram configuration and THI scores prior to treatment were significantly related to the effectiveness of sound masking therapy. Patients with a flat audiogram, being younger in age and having higher THI scores were more likely to have positive outcomes. These findings show the importance of individual factors in predicting the likelihood of therapeutic effectiveness.

Participants with a flat audiogram were more likely to respond positively to the intensive sound masking intervention than those with a HFSS audiogram but there was no relation to an average hearing threshold profile. To our best knowledge, no previous study has investigated the influence of audiometric configuration on the outcome of tinnitus intervention, even though the study by Chang et al26 showed that patients with a flat pattern audiogram benefited more from hearing aids compared with those with rising or decreasing audiogram in terms of improvement of psychological handicap and quality of life. The present result is likely to be due to tinnitus characteristics together with their associated hearing status. By recording Transient Otoacoustic Emisions (TEOAEs), Kim et al17 found that normal TEOAE rates were significantly higher in patients with tinnitus with a flat audiogram than those in the HFGS and HFSS groups. Moreover, patients with tinnitus with HFSS had significantly lower response rates of TEOAEs at 3, 4 and 6 kHz than atients with tinnitus with a flat audiogram. Therefore, better hearing status in patients wit tinnitus with a flat audiogram may be the underlying factor, which is consistent with the previous finding reported by Theodoroff et al.1 However, this result should be interpreted with caution due to the retrospective nature of this study. Further prospective research is needed using systematic approaches, such as randomised controlled trials.27

Higher THI scores before treatment were correlated with a better response to sound masking. These results are consistent with the findings of Koizumi et al11 and Theodoroff et al,1 who found tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) more effective in patients with higher THI scores. Koizumi et al11 further suggested that TRT should be introduced to patients with tinnitus with a THI score higher than 50 points. Because overall THI score may reflect the distress in patients with tinnitus, these results suggested that sound masking may be regarded as a useful therapy to alleviate the distress cause by tinnitus, particularly in patients in severe distress.28

There are several possible mechanisms behind sound masking therapy, but the exact mechanism is still unclear. Overall, it is generally accepted that there is a reduction in response to a signal due to the presence of another. The neuro-physiological mechanism can be explained through an understanding that the neural activity caused by the first sound signal (tinnitus) is reduced by the neural activity of the other sound (eg, masking noise). For example, recent magnetoencephalography (MEG) data reported by Adjamianet al,29 support the efficacy of sound masking on psychological handicap (depression and anxiety), reflecting a reduction in delta band activity, which is considered a possible neuronal marker for the effect of masking.7

Various advanced neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI and PET are valuable tools to explore the mechanism of tinnitus. For example, Lanting et al30 used fMRI and PET to identify enhanced neural activity across several areas of the central auditory system. They also found that neural activity in non-auditory areas (ie, frontal areas, limbic system and cerebellum) seemed to be associated with the perception of tinnitus. Further studies comparing the subjective perception of tinnitus and central neural activity changes between pre and post sound masking therapy are needed to clarify the neural marker and the mechanisms of effective sound masking therapy.

In the present study, younger age had a positive effect on the benefits of sound masking therapy. Von Wedel et al31 suggested that younger patients with tinnitus are more likely to report distress and tinnitus annoyance than older patients. Moreover, Seydel et al32 demonstrated that younger tinnitus subjects had more severe distress than older tinnitus subjects, due to higher levels of occupational and personal stress among younger subjects.32 As a result, younger subjects are likely to gain more benefit in alleviating their high levels of distress by sound masking intervention.7 Another explanation could be the better coping capability of younger patients with tinnitus than older subjects.32

There are some limitations in the present study that need to be considered. Influencing factors associated with long-term effectiveness of sound masking therapy could not be investigated due to a patient adherence issue. Moreover, because of the retrospective design of the study, only THI was used to measure the effectiveness of sound masking therapy. Additional tinnitus measurements could be taken into account, such as a visual analogue scale, and the Tinnitus Functional Index.33 Therefore, future prospective longitudinal research is needed to explore the long-term effectiveness of sound masking therapy, together with its associated influencing factors.

Conclusion

This retrospective study suggests that audiometric configuration, age and THI scores pre treatment are predictive of beneficial sound masking outcomes. Further analysis indicates that patients with tinnitus with a flat audiogram configuration are more likely to achieve a successful intervention compared with those with high-frequency steeply sloping audiograms. Gender, tinnitus laterality, duration and hearing threshold are not related to the effectiveness of intensive sound masking treatment. However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the retrospective nature of this study. A future randomised control study is needed to provide further evidence relating to prognostic factors (eg, audiometric configuration, age THI score) and their contribution to the effectiveness of tinnitus interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Christopher Wigham for his proof reading.

Footnotes

YC and QZ contributed equally.

Contributors: YXC and YQZ contributed to the study design. HDY, JJJ, XYH and XYZ collected the data. QZ and HDY designed the plan of analysis. QZ, HX and SJC performed the final analyses. YXC, FZ, HJM and XTC drafted the manuscript and interpreted the results. All authors made substantive editorial contributions at all stages of manuscript preparation.

Funding: This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81600808 and 81570935), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2016A030313318 and 2015A030310134) and National University Student Innovation Training Scheme (Grant No. 201601133).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.6c1s4.

References

- 1. Theodoroff SM, Schuette A, Griest S, et al. Individual patient factors associated with effective tinnitus treatment. J Am Acad Audiol 2014;25:631–43. 10.3766/jaaa.25.7.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Han BI, Lee HW, Kim TY, et al. Tinnitus: characteristics, causes, mechanisms, and treatments. J Clin Neurol 2009;5:11–19. 10.3988/jcn.2009.5.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen YC, Wang F, Wang J, et al. Resting-state brain abnormalities in chronic subjective tinnitus: a meta-analysis. Front Hum Neurosci 2017;11:22 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen YC, Zhang J, Li XW, et al. Aberrant spontaneous brain activity in chronic tinnitus patients revealed by resting-state functional MRI. Neuroimage Clin 2014;6:222–8. 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baguley DM. Mechanisms of tinnitus. Br Med Bull 2002;63:195–212. 10.1093/bmb/63.1.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kleinjung T, Steffens T, Sand P, et al. Which tinnitus patients benefit from transcranial magnetic stimulation? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137:589–95. 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoare DJ, Searchfield GD, El Refaie A, et al. Sound therapy for tinnitus management: practicable options. J Am Acad Audiol 2014;25:62–75. 10.3766/jaaa.25.1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hobson J, Chisholm E, El Refaie A. Sound therapy (masking) in the management of tinnitus in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:D6371 10.1002/14651858.CD006371.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hobson J, Chisholm E, El Refaie A. Sound therapy (masking) in the management of tinnitus in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;12:D6371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koizumi T, Nishimura T, Sakaguchi T, et al. Estimation of factors influencing the results of tinnitus retraining therapy. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2009:40–5. 10.1080/00016480902933072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ariizumi Y, Hatanaka A, Kitamura K. Clinical prognostic factors for tinnitus retraining therapy with a sound generator in tinnitus patients. J Med Dent Sci 2010;57:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graul J, Klinger R, Greimel KV, et al. Differential outcome of a multimodal cognitive-behavioral inpatient treatment for patients with chronic decompensated tinnitus. Int Tinnitus J 2008;14:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conrad I, Kleinstäuber M, Jasper K, et al. The changeability and predictive value of dysfunctional cognitions in cognitive behavior therapy for chronic tinnitus. Int J Behav Med 2015;22:239–50. 10.1007/s12529-014-9425-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hannula S, Bloigu R, Majamaa K, et al. Audiogram configurations among older adults: prevalence and relation to self-reported hearing problems. Int J Audiol 2011;50:793–801. 10.3109/14992027.2011.593562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim SY, Jeon YJ, Lee JY, et al. Characteristics of tinnitus in adolescents and association with psychoemotional factors. Laryngoscope 2017;127:2113–9. 10.1002/lary.26334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim SI, Kim MG, Kim SS, et al. Evaluation of tinnitus patients by audiometric configuration. Am J Otolaryngol 2016;37:1–5. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schecklmann M, Vielsmeier V, Steffens T, et al. Relationship between audiometric slope and tinnitus pitch in tinnitus patients: insights into the mechanisms of tinnitus generation. PLoS One 2012;7:e34878 10.1371/journal.pone.0034878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Demeester K, van Wieringen A, Hendrickx JJ, et al. Prevalence of tinnitus and audiometric shape. B-ENT 2007;3 (Suppl 7):37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim TS, Yoo MH, Lee HS, et al. Short-term changes in tinnitus pitch related to audiometric shape in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Auris Nasus Larynx 2016;43:281–6. 10.1016/j.anl.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Teismann H, Okamoto H, Pantev C. Short and intense tailor-made notched music training against tinnitus: the tinnitus frequency matters. PLoS One 2011;6:e24685 10.1371/journal.pone.0024685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu Y, Zhou H, Yang D. [Clinical observation of the relationship between tinnitus masking curve and masking therapy result]. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2009;23:588–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:143–8. 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim BJ, Chung SW, Jung JY, et al. Effect of different sounds on the treatment outcome of tinnitus retraining therapy. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2014;7:87–93. 10.3342/ceo.2014.7.2.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zeman F, Koller M, Figueiredo R, et al. Tinnitus handicap inventory for evaluating treatment effects: which changes are clinically relevant? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;145:282–7. 10.1177/0194599811403882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang YS, Choi J, Moon IJ, et al. Factors associated with self-reported outcome in adaptation of hearing aid. Acta Otolaryngol 2016;136:905–11. 10.3109/00016489.2016.1170201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scherer RW, Formby C, Gold S, et al. The Tinnitus Retraining Therapy Trial (TRTT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:396 10.1186/1745-6215-15-396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. von Wedel H, von Wedel UC, Streppel M, et al. [Effectiveness of partial and complete instrumental masking in chronic tinnitus. Studies with reference to retraining therapy]. HNO 1997;45:690–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adjamian P, Sereda M, Zobay O, et al. Neuromagnetic indicators of tinnitus and tinnitus masking in patients with and without hearing loss. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2012;13:715–31. 10.1007/s10162-012-0340-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lanting CP, de Kleine E, van Dijk P. Neural activity underlying tinnitus generation: results from PET and fMRI. Hear Res 2009;255:1–13. 10.1016/j.heares.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. von Wedel H, von Wedel UC, Zorowka P. Tinnitus diagnosis and therapy in the aged. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1990;476:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seydel C, Haupt H, Olze H, et al. Gender and chronic tinnitus: differences in tinnitus-related distress depend on age and duration of tinnitus. Ear Hear 2013;34:661–72. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828149f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hall DA, Haider H, Szczepek AJ, et al. Systematic review of outcome domains and instruments used in clinical trials of tinnitus treatments in adults. Trials 2016;17:270 10.1186/s13063-016-1399-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herraiz C, Hernandez FJ, Toledano A, et al. Tinnitus retraining therapy: prognosis factors. Am J Otolaryngol 2007;28:225–9. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.