Abstract

Objective

To test a priori hypothesis of an association between season-specific cold spells and sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Methods

We conducted a case–crossover study of 3614 autopsy-verified cases of SCD in the Province of Oulu, Finland (1998–2011). Cold spell was statistically defined by applying an individual frequency distribution of daily temperatures at the home address during the hazard period (7 days preceding death) and 50 reference periods (same calendar days of other years) for each case using the home coordinates. Conditional logistic regression was applied to estimate ORs for the association between the occurrence of cold spells and the risk of SCD after controlling for temporal trends.

Results

The risk of SCD was associated with a preceding cold spell (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.00, 1.78). A greater number of cold days preceding death increased the risk of SCD approximately 19% per day (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.32). The association was strongest during autumn (OR 2.51; 95% CI 1.27 to 4.96) and winter (OR 1.70; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.55) and lowest during summer (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.15 to 1.18) and spring (OR 0.89; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.79). The association was stronger for ischaemic (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.12 to 2.13) than for non-ischaemic SCD (OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.45) verified by medicolegal autopsy.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that there is an association between cold spells and SCD, that this association is strongest during autumn, when the weather event is prolonged, and with cases suffering ischaemic SCD. These findings are subsumed with potential prevention via weather forecasting, medical advice and protective behaviour.

Keywords: sudden cardiac death, sudden death, cold spell, temperature, weather, cardiac epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cases from the world’s largest autopsy-verified data set of sudden cardiac death were linked with 51 years of coordinate-specific weather data at their home coordinates.

Individual frequency distributions of daily temperatures at each home coordinate were used to define unusually cold weather pertinent to the location and time of death.

Stratified analyses between ischaemic and non-ischaemic sudden cardiac death in relation to unusually cold weather were performed based on medicolegal autopsy findings.

The study did not elaborate the relative roles of temperature and air pollution during the weather phenomenon.

Behavioural activity patterns of the cases for the week preceding death were not available.

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the leading cause of death, currently estimated to represent 60% of all cardiovascular deaths.1 2 In contrast to acute myocardial infarction, or most chronic cardiovascular diseases, SCD affects individuals who have been considered at zero-to-low risk of cardiovascular death.3 4 In over half of the cases, SCD is the first manifestation of the underlying cardiac disease.3 It commonly occurs in the prime of life,1 affecting approximately one in every five people in the western society.4 Substantial global research efforts have yielded specific risk markers of SCD, such as certain abnormalities in ECG.4 However, predicting SCD on both an individual level and in the general population remains challenging.4

Weather, on the other hand, can be predicted and preventive measures taken. There is substantial evidence that cardiovascular mortality is associated with the temperature of the day or the preceding days.5 6 According to our recent systematic review and meta-analysis, cold spells are associated with 11% increase in cardiovascular mortality rates around the world.6 Whether or not and how much SCD might contribute to these associations is unknown. There are only a handful of studies on the association between cold weather and SCD,7–10 and one study on the association between cold spells and ischaemic SCD.11 We recently showed an association between cold spells and ischaemic SCD, with effect modification by cardioprotective medications.11 There is also considerable evidence on the association between cold ambient temperature and acute myocardial infarction,12–14 with pathophysiological basis previously described.15 Whether or not and how much SCD might contribute to these associations is also unknown, since SCD entails a broader range of pathologies and has many distinctive features from acute myocardial infarction or out-of-hospital coronary death.4 16–18

Based on the international shift from broad to specific approaches on SCD risk assessment,4 18 our general objective was to estimate the association between cold weather and SCD applying measures that maximise the accuracy of both the exposure and the outcome. Our specific objectives were to test the a priori hypotheses that cold spells are associated with the risk of SCD; that the effect is stronger according to an increasing number of unusually cold days preceding the death; and to assess potential seasonal modification of the effect; to identify susceptible groups in terms of age and sex; to investigate if the association is stronger for ischaemic than for non-ischaemic SCD.

Methods

This study is based on a priori protocol accessible at www.oulu.fi/cerh/node/31850. STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were applied to ensure transparency of the reporting of results.

Study design and population

We conducted a case–crossover study to assess the relation between cold spells and SCD. Case–crossover design is well suited for studying the effects of transient short-term exposures on the risk of acute events.19 We assigned to each case a hazard period (HP) of 7 days preceding the day of death and 50 reference periods (RP) comprising of the same calendar days of the other years of the study period 1961–2011.

The study population included 3707 cases from The Finnish Study of Genotype and Phenotype Characteristics of Sudden Cardiac Death (FinGesture) in the province of Oulu, Northern Finland,16 who died between 1998 and 2011. Ninety-three cases were excluded because their home coordinates for the time of death were unavailable. This resulted in 3614 cases. All cases underwent postmortem examinations at the Department of Forensic Medicine of the University of Oulu. Case validation was conducted by a forensic specialist through medicolegal autopsy, detailed histological sampling, full medical history and police reports. Those with any other cause than SCD, including intoxications during an acute coronary event, were excluded. All witnessed SCDs occurred within 6 hours of the onset of the forewarning symptoms. All unwitnessed victims of SCD were seen alive and in a normal state of health within 24 hours preceding the death. Postmortem studies of unexpected death are mandatory in Finland, and the selection bias in victims with unexpected SCD is minimal.16 Hence, this provides unique opportunity to cover the entire breadth of SCD cases in the general population.

Exposure assessment

The home coordinates (EUREF ETRS-TM35FIN) of the cases at the time of death were retrieved from the Population Register Centre. Geographical Information System (GIS) was used to allocate daily temperatures at the home coordinates of each case for the days in HP and RP over the study years 1961–2011. For this purpose, a data set containing minimum, mean and maximum daily temperatures in the study period was obtained from the Finnish Meteorological Institute. In this data set, point measurements have been interpolated onto a 10×10 km grid covering the whole of Finland using a Kriging method.20 We organised the temperature data set into a GIS database, and GIS-based functions were then used to extract temperature values from the database according to location and date.

Individual frequency distributions of daily temperatures during the HP and RP for the home coordinates of each case were formed. Cold spell was defined as a period of ≥3 consecutive days with daily minimum temperature below the fifth percentile of the individual frequency distribution. Conceptually, this approach identifies events that are unusually cold in the respective place and time of the year. We used the same frequency distributions and thresholds to identify single cold days and any combination of single cold days in different definitions of unusually cold weather used in this study (eg, 2 consecutive days). Individual exposure assessment was conducted for the HP. In contrast to this, the occurrence of cold spells during the RPs represents the usual exposure at the individual’s place of residence. Thus, we estimated the occurrence of the weather phenomenon during the two period types and analysed whether the possible differences in the occurrence could be explained by random variation.

To describe the general weather during the study, we formed a time series of minimum, mean and maximum daily temperatures at the central coordinate 27.39E/64.79N of the province of Oulu, Finland, over the study period 1961–2011 using the same databases, programmes and methods as described above.

Statistical methods

Conditional logistic regression was applied to estimate the ORs and 95% CIs representing the proportion of cold spells occurring during HP and RP. Conditional logistic regression was performed using PROC PHREG in SAS (SAS, V.9.4; SAS Institute) using the discrete logistic model and forming a stratum for each ID. An indicator variable consisting of 5-year intervals over the study period was formed to control for long time trends in the occurrence of cold spells. Season, month, day of the week, weekends and holidays were controlled by design.19 We conducted a priori stratified analyses according to an increasing number of cold days preceding death and according to the season of death. Calendar time was used to define the four seasons (autumn, September to November; winter, December to February; spring, March to May; summer, June to August). We conducted a priori subgroup analyses using gender, age and ischaemic versus non-ischaemic aetiology of the death confirmed by the autopsy finding as BY-variables in conditional logistic regression. Cases aged under 35 were excluded from the subgroup analyses a priori because of the few numbers (n=40) and expected heterogeneity. The difference between ORs in each subgroup was estimated using Q-statistics for heterogeneity, by applying the DerSimonian-Laird method using a SAS macro provided by Hertzmark and Spiegelman.21 22

Results

The characteristics of the study population are shown in table 1. Online supplementary table 1 elaborates the underlying cardiac disease of the victims of non-ischaemic SCD, with diagnostic criteria previously reported.16

Table 1.

The characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Men, n (%) | Women, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

| All | 2878 | 736 | 3614 |

| Age | |||

| 0–34 | 32 (1.1) | 8 (1.1) | 40 (1.1) |

| 35–64 | 1583 (55.0) | 231 (31.4) | 1814 (50.2) |

| ≥65 | 1263 (43.9) | 497 (67.5) | 1760 (48.7) |

| Autopsy finding | |||

| Ischaemic | 2214 (76.9) | 545 (74.0) | 2759 (76.3) |

| Non-ischaemic | 664 (23.1) | 191 (26.0) | 855 (23.7) |

| Season of death | |||

| Autumn | 688 (23.9) | 198 (26.9) | 886 (24.5) |

| Winter | 688 (23.9) | 174 (23.6) | 862 (23.9) |

| Spring | 802 (27.9) | 188 (25.5) | 990 (27.4) |

| Summer | 700 (24.3) | 176 (23.9) | 876 (24.2) |

bmjopen-2017-017398supp001.pdf (86KB, pdf)

A total of 3974 location-specific cold spells were identified for the analyses. The distribution parameters of daily temperatures in the province of Oulu over the study period 1961–2011 are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

The distribution parameters of daily temperatures (T) in the province of Oulu, Finland, over the study period 1961–2011

| Variable | Autumn | Winter | Spring | Summer | Total |

| Mean average T (SD), °C | +1.7 (6.7) | −10.5 (7.9) | +0.4 (7.2) | +13.8 (3.7) | +1.4 (10.8) |

| T range, °C | 58.6 | 49.7 | 61.9 | 35.7 | 74.3 |

| Lowest minimum T, °C | −34.4 | −41.3 | −34.2 | −2.7 | −41.3 |

| Highest maximum T, °C | +24.2 | +8.4 | +27.7 | +33.0 | +33.0 |

| T quartiles, Q1, Q2, Q3, °C | −2.1,+2.1,+6.4 | −16.0,–9.2, −4.1 | −3.9,+0.8,+5.0 | +11.3,+13.7,+16.2 | −5.5,+1.6,+10.3 |

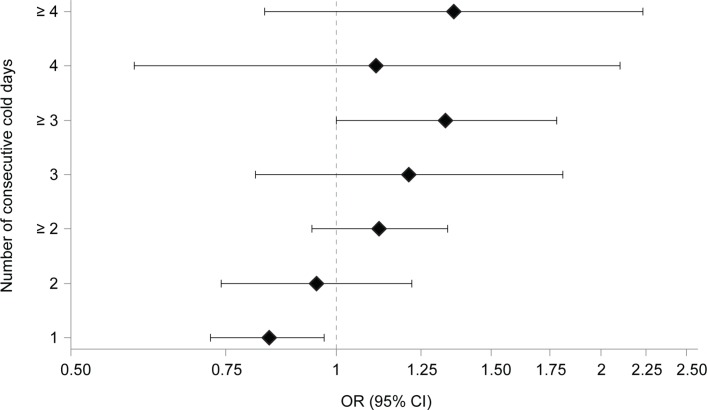

Cold spells were associated with an increased risk of SCD (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.78). The effect estimate for a singular cold day was below unity (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.72 to 0.97), and increasing the number of cold days occurring during the HP increased the risk of SCD approximately 19% per day (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.32). Figure 1 shows the relation between the occurrence of different combinations of consecutive days below the threshold temperature and the risk of SCD.

Figure 1.

The relation between sudden cardiac death and consecutive days below threshold temperature. X-axis presents the ORs and 95% CIs on a logarithmic scale; y-axis presents the number of consecutive days with daily minimum temperature below threshold occurring during the week preceding death. Each effect estimate is derived by a stratified analysis according to the number of days, an integer being the exact number of consecutive days, and ‘≥’ indicating the minimum number of consecutive days (eg, at least n consecutive days).

In the analyses stratified by season, distinct seasonal differences in the association between cold spells and SCD were observed. The effect estimates were highest during autumn and winter, and lowest during summer and spring (table 3), while the underlying seasonal variation in the incidence of SCD was negligible (table 1).

Table 3.

The relation between the occurrence of cold spells and the risk of SCD based on stratified analyses by season

| Season | OR (95% CI) |

| Autumn | 2.51 (1.27 to 4.96) |

| Winter | 1.70 (1.13 to 2.55) |

| Spring | 0.89 (0.45 to 1.79) |

| Summer | 0.42 (0.15 to 1.18) |

SCD, sudden cardiac death.

We conducted several subgroup analyses for the purpose of elaborating effect modification of the relation between cold spells and SCD (table 4). There were no distinct differences in sensitivity to cold spells between subjects aged over 65 years and those aged 35–64 years. Likewise, gender did not significantly modify the effect.

Table 4.

The relation between the occurrence of cold spells and the risk of SCD by various subgroups of cases over 34 years of age

| Subgroup | OR (95% CI) | Q-statistics (p) |

| Age | ||

| 35–64 | 1.28 (0.84 to 1.97) | 0.03 (0.84) |

| ≥65 | 1.36 (0.91 to 2.04) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.30 (0.94 to 1.81) | 0.04 (0.83) |

| Female | 1.41 (0.74 to 2.67) | |

| Autopsy finding | ||

| Ischaemic | 1.55 (1.12 to 2.13) | 3.85 (0.05) |

| Non-ischaemic | 0.68 (0.32 to 1.45) |

SCD, sudden cardiac death.

In the subgroup analysis according to the aetiology of underlying structural heart disease at autopsy, the effect estimate for ischaemic SCD was greater than for non-ischaemic SCD, confirmed by Q-statistics 3.85, p=0.05 (table 4).

Discussion

Cold spells were associated with an increased risk of SCD. Additional number of cold days during the 1-week period preceding death increased the risk of SCD by approximately 19% per cold day. The association between cold spells and SCD was strongest during autumn and winter, and non-existent during spring and summer. Cold spells increased the risk of SCD caused by ischaemic heart disease, whereas there was no association with non-ischaemic aetiology.

The incidence of SCD was similar during different seasons (table 1), but the associations between seasonally defined cold spells and the risk of SCD varied significantly depending on the season (table 3). The highest effect estimate during autumn promotes the concept of relative, instead of absolute, temperature playing an important role in the association.6 The first few cold temperatures of autumn might involve an increased risk due to lack of cold habituation and the associated aggravated physiological responses,23 or due to a delay in behavioural adaptation such as appropriate clothing and sufficient indoor heating.24 The contrast in effect estimates between autumn and spring, both of which have similar temperature indices (table 2), and similar incidence of SCD (table 1), is noteworthy. A gradual change towards colder temperatures or the rapidly increasing temperature range after summer might modify the association with cold spells. The contrast in the effect estimates between winter and summer suggests that absolute temperature level, complementary to the relative or changing temperature, plays a role in the association. None of these interpretations are in conflict with previous evidence, and the results suggest that physicians should start advising cardiologic patients on the risks associated with cold weather before winter.

Additional number of cold days during the 1-week period preceding death increased the risk of SCD. This could indicate sustained cold-related physiological strain and/or increasing probability of exposure. On the other hand, the protective effect of a single cold day might be explained by protective behaviour such as first staying indoors but then having to return to normal behaviour. Both speculations presume that the most harmful exposure during cold spells occurs outdoors, which has not been confirmed.6

Cold spells increased the risk of SCD caused by ischaemic heart disease, whereas there was no association with non-ischaemic aetiology. This finding, if repeated in other settings, might provide further insight into the cold-induced pathological pathways of SCD. We have recently summarised some of the hypothesised pathways between cold spells and SCD.11 Briefly, evidence from experimental studies shows that exposure to cold ambient temperature induces changes in blood composition, loss of plasma fluid, haemoconcentration and redistribution of thrombogenic factors25 26; induces peripheral vasoconstriction and a sudden increase in systemic vascular resistance, systolic and diastolic and central aortic blood pressures, preload, cardiac output and oxygen demand of the heart15 27; and under experimental conditions induces coronary spasm in susceptible individuals.28 All these factors increase specifically the susceptibility to SCD caused by acute ischaemic event, which was evident in our findings. Cooling of the face and body also results in simultaneous coactivation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, which may be proarrhythmic given suitable myocardial substrates.29 This pathway might be less significant during cold weather, since cold spells were not associated with an increased risk of SCD in subjects with non-ischaemic heart disease. However, no definite conclusions should be made on the pathways or their relevance before extensive studies into the topic. Insight might offer direct targets for intervention with pharmacological agents, as recently shown.11

Strengths and limitations

Improvements were introduced to the definition of cold spell based on the findings of our recent systematic review and meta-analysis.6 In the reviewed studies, cold spell threshold was commonly defined as the first to fifth percentiles of the frequency distribution of the daily temperatures over the entire study period. Conceptually, this tends to place all cold spells in cold winter months and disregards unusually cold events occurring during warmer months. Because the adverse effects of cold temperatures have been shown to be more pronounced in warmer climates,5 24 or because lack of cold habituation during warmer months could elicit aggravated cardiovascular responses to a suddenly decreasing temperature,23 it is reasonable to ask whether exceptionally cold weather during months other than those of winter could also have adverse effects on health. Our approach identifies events that are unusually cold in the respective place and time of the year. It is telling that we would not have been able to observe the highest risk during autumn without this approach. Generally speaking, frequency distribution-based exposure assessment is beneficial in terms of being able to generalise results, making it easier to compare estimates obtained from different geographical regions.6 It would be interesting to see whether comparable results obtained with these methods would produce different effect estimates in different climates.30

There is evidence on the benefits of confirming the diagnosis and mode of sudden death by medicolegal autopsy in order to provide unbiased information on the incidence of SCD.2 3 18 It is difficult to distinguish between cardiac and non-cardiac cause of sudden death without an autopsy, since many conditions that evolve rapidly, such as aortic dissection, massive pulmonary embolism or stroke, can lead to sudden collapse and death. We conducted our analyses using the world’s largest autopsy-verified data set of SCD. We took advantage of the individual-level nature of the data by forming and assessing individual frequency distributions of temperatures at each home coordinate to define cold weather for the cases.

The present study assessed the association between cold spells and occurrence of SCD without elaborating the relative roles of temperature and air pollution. In other words, we estimated the overall effect of the entire weather phenomenon rather than focusing on individual physical parameters related to this phenomenon. Ours is the primary question from clinical and public health practice, although additional information on the contribution on air pollution in general and specific compounds would be interesting. If part of the effects of cold spells was mediated by increased air pollution levels, adjustment for air pollution would lead to underestimation of the overall effects of cold spells.

Although we estimated the outdoor temperatures for each home coordinate for the week preceding the death of the resident, the behavioural activity patterns for the week preceding death were not available. Therefore, it was not possible to estimate how much time the cases spent outdoors, and what kind of thermal patterns they were exposed to. This is a common limitation in studies without personal measuring devices and activity pattern diaries. It also remains an important question how changes in weather manifest as changes in different indoor environments, and whether some of these changes mediate the harmful effects of weather. Variations between individuals in their attitudes towards cold weather, use of protective clothing, physical activity, comorbidity, substance abuse and use of medications are likely to exist in our data and in the general population. Combinations of these and other individual factors might influence personal risk profiles in ways that are difficult to predict from an epidemiological stance, and although our results can be generalised over a population, they cannot be directly translated to individual risk. It is reasonable to assume that the association between cold spells and risk of SCD is modified by a variety of factors still unknown.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that there is an association between cold spells and SCD, that this association is strongest during autumn, when the weather event is prolonged, and with cases suffering ischaemic SCD. These findings are subsumed with potential prevention via weather forecasting, medical advice and protective behaviour. We believe more studies on the associations between cold weather and SCD should identify potential targets for intervention, be it pharmacological modification, diagnosis and treatment of underlying cardiovascular diseases, or behavioural patterns during cold weather.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NRIR and JJKJ designed the study. MLK contributed significantly to the performing of the medicolegal autopsies over 1998–2011. EH complemented the autopsy data to constitute the FinGesture database under the supervision of MJJ and HVH. HA collected the weather data from Finnish Meteorological Institution, designed and applied the GIS model to produce the case-specific exposure data. EMSM designed the SAS program for the main analyses and executed the analyses together with NRIR. TMI contributed expertise in cold-related physiology and substantial scientific input in interpretation of the results. HVH contributed expertise in cardiology and substantial scientific input in the interpretation of the results. JJKJ contributed expertise in epidemiology and public health and substantial scientific input in interpretation of results. NRIR and JJKJ drafted the manuscript and all authors have accepted the final version. JJKJ and HVH have equal senior authorship, had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This work was funded by the Research Council for Health, Academy of Finland (grant no. 266314 and 267435), University of Oulu Strategic Funding for CERH, Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Sigrid Juselius Foundation, and Foundation for Cardiovascular Disease. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors are independent of the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Oulu University Hospital (ID of the approval EETTMK: 18/2014). National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health (Valvira) has approved the review of postmortem data by the investigators.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL, et al. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:216–25. 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chugh SS, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: clinical and research implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2008;51:213–28. 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myerburg RJ, Junttila MJ. Sudden cardiac death caused by coronary heart disease. Circulation 2012;125:1043–52. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.023846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wellens HJ, Schwartz PJ, Lindemans FW, et al. Risk stratification for sudden cardiac death: current status and challenges for the future. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1642–51. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Analitis A, Katsouyanni K, Biggeri A, et al. Effects of cold weather on mortality: results from 15 European cities within the PHEWE project. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:1397–408. 10.1093/aje/kwn266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryti NR, Guo Y, Jaakkola JJ. Global association of cold spells and adverse health effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect 2016;124:12–22. 10.1289/ehp.1408104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Töro K, Bartholy J, Pongrácz R, et al. Evaluation of meteorological factors on sudden cardiovascular death. J Forensic Leg Med 2010;17:236–42. 10.1016/j.jflm.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber Y, Jacobsen SJ, Killian JM, et al. Seasonality and daily weather conditions in relation to myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979 to 2002. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:287–92. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arntz HR, Müller-Nordhorn J, Willich SN. Cold monday mornings prove dangerous: epidemiology of sudden cardiac death. Curr Opin Crit Care 2001;7:139–44. 10.1097/00075198-200106000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz A, Biron A, Ovsyshcher E, et al. Seasonal variation in sudden death in the Negev desert region of Israel. Isr Med Assoc J 2000;2:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryti NR, Mäkikyrö EM, Antikainen H, et al. Cold spells and ischaemic sudden cardiac death: effect modification by prior diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease and cardioprotective medication. Sci Rep 2017;7:41060 10.1038/srep41060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Haines A, et al. Effects of ambient temperature on the incidence of myocardial infarction. Heart 2009;95:1760–9. 10.1136/hrt.2009.175000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Haines A, et al. Short term effects of temperature on risk of myocardial infarction in England and Wales: time series regression analysis of the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) registry. BMJ 2010;341:c3823 10.1136/bmj.c3823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen R, Li T, Cai J, et al. Extreme temperatures and out-of-hospital coronary deaths in six large Chinese cities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:1119–24. 10.1136/jech-2014-204012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manou-Stathopoulou V, Goodwin CD, Patterson T, et al. The effects of cold and exercise on the cardiovascular system. Heart 2015;101:808–20. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hookana E, Junttila MJ, Puurunen VP, et al. Causes of nonischemic sudden cardiac death in the current era. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:1570–5. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huikuri HV, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ. Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1473–82. 10.1056/NEJMra000650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chugh SS, Jui J, Gunson K, et al. Current burden of sudden cardiac death: multiple source surveillance versus retrospective death certificate-based review in a large U.S. community. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:1268–75. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:144–53. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venäläinen A, Heikinheimo M. Meteorological data for agricultural applications. Phys Chem Earth 2002;27:1045–50. 10.1016/S1474-7065(02)00140-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertzmark E, Spiegelman D. The SAS METAANAL Macro. Written for the Channing Laboratory 2012. http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/donna-spiegelman/software/metaanal/ (Accessed 24 june 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makinen TM. Different types of cold adaptation in humans. Front Biosci 2010;2:1047–67. 10.2741/s117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Eurowinter Group. Cold exposure and winter mortality from ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, and all causes in warm and cold regions of Europe. Lancet 1997;349:1341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keatinge WR, Coleshaw SR, Cotter F, et al. Increases in platelet and red cell counts, blood viscosity, and arterial pressure during mild surface cooling: factors in mortality from coronary and cerebral thrombosis in winter. Br Med J 1984;289:1405–8. 10.1136/bmj.289.6456.1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neild PJ, Syndercombe-Court D, Keatinge WR, et al. Cold-induced increases in erythrocyte count, plasma cholesterol and plasma fibrinogen of elderly people without a comparable rise in protein C or factor X. Clin Sci 1994;86:43–8. 10.1042/cs0860043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hintsala H, Kandelberg A, Herzig KH, et al. Central aortic blood pressure of hypertensive men during short-term cold exposure. Am J Hypertens 2014;27:656–64. 10.1093/ajh/hpt136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raizner A, Chahine RA, Ishimori T, et al. Provocation of coronary artery spasm by the cold pressor test. Circulation 1980;62:925–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shattock MJ, Tipton MJ. ’Autonomic conflict': a different way to die during cold water immersion? J Physiol 2012;590:3219–30. 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.229864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart S, Keates AK, Redfern A, et al. Seasonal variations in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017. 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017398supp001.pdf (86KB, pdf)