Abstract

Objective

To estimate the proportion of systematic reviews that meet the optimal information size (OIS) and assess the impact heterogeneity and effect size have on the OIS estimate by type of outcome (eg, mortality, semiobjective or subjective).

Methods

We carried out searches of Medline and Cochrane to retrieve meta-analyses published in systematic reviews from 2010 to 2012. We estimated the OIS using Trial Sequential Analysis software (TSA V.0.9) and based on several heterogeneity and effect size scenarios, stratifying by type of outcome (mortality/semiobjective/subjective) and by Cochrane/non-Cochrane reviews.

Results

We included 137 meta-analyses out of 218 (63%) potential systematic reviews (one meta-analysis from each systematic review). Of these reviews, 83 (61%) were Cochrane and 54 (39%) non-Cochrane. The Cochrane reviews included a mean of 6.5 (SD 6.1) studies and the non-Cochrane included a mean of 13.2 (SD 10.2) studies. The mean number of patients was 2619.1 (SD 6245.8 or median 586.0) for the Cochrane and 19 888.5 (SD 32 925.7 or median 6566.5) patients for the non-Cochrane reviews. The percentage of systematic reviews that achieved the OIS for all-cause mortality outcome were 0% Cochrane and 25% for non-Cochrane reviews; for semiobjective outcome 17% for Cochrane and 46% for non-Cochrane reviews and for subjective outcome 45% for Cochrane and 72% for non-Cochrane reviews.

Conclusions

The number of systematic reviews that meet an optimal information size is low and varies depending on the type of outcome and the type of publication. Less than half of primary outcomes synthesised in systematic reviews achieve the OIS, and therefore the conclusions are subject to substantial uncertainty.

Keywords: meta-analysis, systematic review, optimal information size, trial sequential analysis, heterogeneity, effect size

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to estimate the optimal information size by type of outcome.

This study includes only systematic reviews from the Cochrane library and the top five general medical journals; therefore, our results may not be generalisable to systematic reviews published in other journals.

Introduction

The concept of optimum information size (OIS) was first proposed in 1998 by Pogue et al1 2 as ‘the minimum amount of information required in the collective literature for reliable conclusions about an intervention to be reached’. This OIS estimate is based on standard sample size calculations. For example, the required number of participants (information size) for a meta-analysis should match those required in an adequately powered single trial.3 Other measures of information size have been proposed4 5; however, the OIS involves a relatively simple calculation, which under some scenarios will underestimate the information required to define whether firm evidence has been reached to draw robust conclusions.6 Brok et al3 demonstrated, in a subset of Cochrane reviews, that many meta-analyses have false-positive results due to insufficient information, and Turner et al showed that most meta-analysis do not have sufficient power to identify even moderate effects.7 8

Sample size calculation and the OIS are influenced by several variables such as the control event rate (CER) (baseline risk), effect size, the power and the alpha value. Deciding on which values to use can be difficult and is typically based on values observed or estimated from the meta-analysis or one of the included studies. In addition, increased variation can also effect the estimate of the OIS, and there is currently no consensus about which value of heterogeneity should be used to calculate the OIS.

The OIS can help determine the stability of an effect and whether treatment effect estimates are likely to differ based on further information. However, they are difficult to define in advance, and there is no consensus regarding the alpha (significance) or power value used at the outset.

It is therefore not currently known if evidence accumulation and its associated OIS depend on the type of outcome studied and if this varies by publication type (Cochrane or non-Cochrane review). Therefore, we set out to quantify this by studying systematic reviews (SRs) published in the Cochrane Library and the top five general medical journals and in the process describe the impact that observed variation in heterogeneity and effect size (relative risk reduction (RRR)) have on the OIS estimation.

Methods

We defined two sets of SRs to evaluate: Cochrane and non-Cochrane. We identified all Cochrane SRs published during 2010–2012 through the Archie Database (http://archie.cochrane.org), which contains all Cochrane published reviews and allows electronic searching. We randomly selected a total of 120 of these based on random numbers generated using Microsoft Excel for inclusion.

To search for non-Cochrane reviews, we identified all SRs with meta-analyses published in the top five general medical journals (The New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, The Journal of the American Medical Association, Internal Medicine, Annals of Internal Medicine and British Medical Journal) using the following search strategy in Medline (PubMed): ‘BMJ’[Journal] OR ‘Ann Intern Med’[Journal] OR ‘JAMA’[Journal] OR ‘Lancet’[Journal] OR ‘N Engl J Med’[Journal] AND (systematic review [ti] OR meta-analysis [pt] OR meta-analysis [ti]) restricted to SRs published during 2010–2012.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

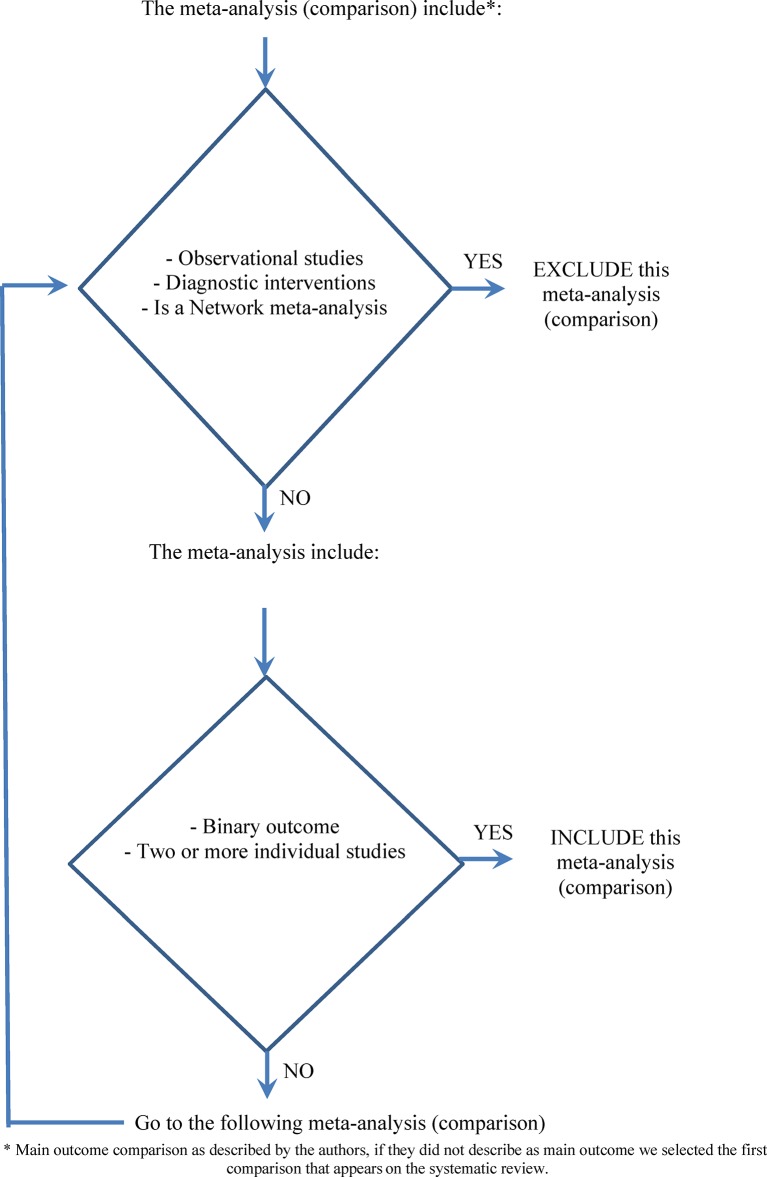

From all the selected Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews, we included one meta-analysis from each. Based on the order the outcomes were reported (eg, outcome 1.1 for Cochrane SRs), we selected the first outcome presented in the meta-analysis that was based on: binary data from two or more individual studies (clinical trials or randomised controlled trials). If the first outcome did not meet this inclusion criteria, we continued through the listed outcomes until one was identified or we had exhausted the list of outcomes reported (figure 1). Meta-analyses that included observational studies, of diagnostic interventions or that were based on network meta-analysis were excluded. Meta-analyses showing no effect (pooled effect=1) or meta-analyses with no events in all included trials were also excluded.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the selection of the meta-analysis (main comparison) in the systematic review.

Data extraction

Full texts were obtained for those abstracts that met the inclusion criteria and assessed for eligibility. One reviewer JMG-A extracted the data, and a second reviewer (RP or NP) checked the data. We developed customised Excel spreadsheets for the data extraction process. From each included meta-analysis, we extracted and calculated the following items: outcome type as defined by Turner9 (‘all cause mortality’, ‘semi-objective’ (cause-specific mortality, major morbidity event) and ‘subjective’ (pain, mental health outcomes)), comparison, number of included patients, number of trials, number of events in each arm, CER, effect size and heterogeneity.

Analyses

We extracted data from each trial and repeated the meta-analysis using random-effects models (DerSimonian and Laird) to account for potential heterogeneity of effects. Estimates for trials with only one group reporting zero events were adjusted with a constant continuity adjustment of 0.5 in each arm (default adjustment in Revman). The obtained estimates for the pooled effect (eg, RR) and I2 were compared with the published results to detect any relevant disagreement, and if required, the analyses were repeated to identify the source of the difference. Meta-analyses and calculation of the OIS were done using Trial Sequential Analysis software (TSA V.0.9)10 freely downloadable at www.ctu.dk/tsa. The TSA software allows meta-analysis of dichotomous or continuous data under fixed or random-effects models and has the option to estimate an information size and the stopping boundary. This estimation of the OIS is based on the alpha spending method (O’Brien Fleming and Lan-DeMets).

To evaluate the impact of changes in heterogeneity and effect size (RRR), we estimated the OIS under different scenarios. For heterogeneity, we analysed three values of heterogeneity: ‘heterogeneity=rep’ as that reported in the meta-analysis using a random-effects model (or obtained from fitting a random effects model if a fixed effect model was used originally), ‘heterogeneity=0’ and ‘heterogeneity=Q3’ (upper quartile or 75th percentile), which was determined based on estimates of predictive distributions published by Rhodes et al.11 These two estimates of ‘heterogeneity=Q3’ and ‘heterogeneity=0’ were chosen as extreme scenarios to evaluate the impact that this parameter has on the OIS. Consistent with Rhodes et al, the estimation of the OIS took into account the outcome type: ‘all cause mortality’, ‘semiobjective’ (cause-specific mortality and major morbidity event) and ‘subjective’ (pain and mental health outcomes) and, for simplicity, was based on assuming an average mean study size between 50 and 200 participants.

To evaluate the impact of effect size on the OIS, we used two different estimates of the effect size for the meta-analyses with mortality outcome: the RRR obtained in each meta-analysis as well as an a priori conservative value of 5% for the RRR as reported by Djulbegovic et al.12 For the transformation of relative risk (RR) measure to RRR, we used the following formula RRR=1 RR. If the RR was greater than 1, we used the RRR as a negative value. We did not determine an alternative estimate for the effect size for the other two outcomes (semiobjective and subjective) as the distribution of possible effects makes the choice of ‘average effect’ difficult to justify. We used only one value, per meta-analysis, for the baseline risk or CER. This was taken to be the median of the proportion of events in the included trials in each meta-analysis, following the method proposed by Hayden et al.13

We used descriptive statistics and plots to quantify differences in CER, effect size and heterogeneity between Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews, stratified by type of outcome (six groups in total). We also determined the proportion of reviews that have achieved the OIS based on reported results and our two extreme scenarios ‘heterogeneity=0’ and ‘heterogeneity=Q3’ comparing between Cochrane and non-Cochrane and again stratifying by type of outcome (‘all-cause mortality’, ‘semiobjective’ and ‘subjective’ outcomes).

The descriptive analysis of the characteristics of included meta-analyses was carried out using SPSS V.22 software.

Results

Search results

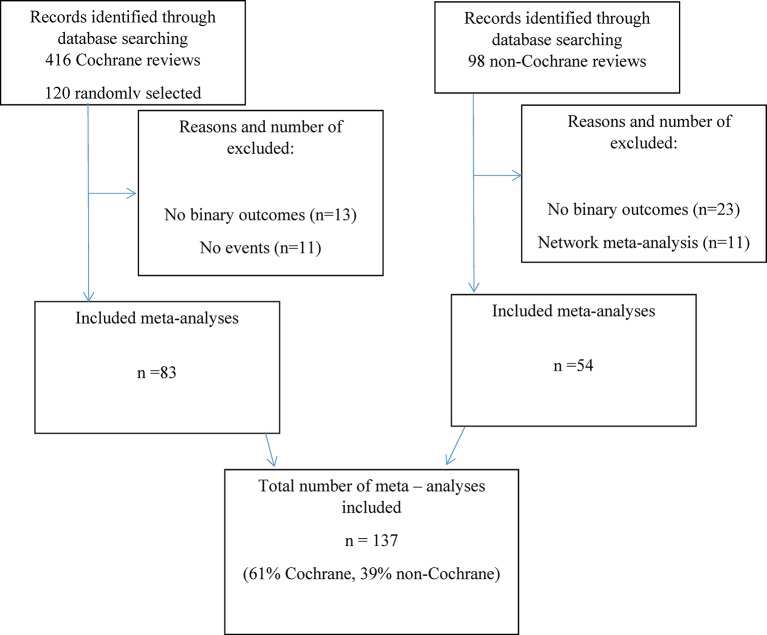

Figure 2 presents a flow chart of the results. We excluded 11 Cochrane SRs due to no events reported in the included trials or due to only one study being included in the review. We included a total of 137 meta-analyses out of 218 (63%) potential SRs (figure 2): 83 (61%) were Cochrane SRs and 54 (39%) non-Cochrane SRs. The Cochrane reviews included a mean of 6.5 (SD 6.1) studies and the non-Cochrane included a mean of 13.2 (SD 10.2) studies. The number of patients was 2619.1 (SD 6245.8 or median 586.0) for the Cochrane and 19 888.5 (SD 32925.7 or median 6566.5) patients for the non-Cochrane reviews.

Figure 2.

Flow chart identification of Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews.

Scenarios under different parameter estimates

Table 1 provides results on the types of outcomes and type of intervention studied for the included meta-analyses by publication type.

Table 1.

Descriptive results of included meta-analyses by type of outcome and intervention

| Cochrane (n=83) | Non-Cochrane (n=54) | All reviews (n=137) | |

| % (n/N) | % (n/N) | % (n/N) | |

| Type of outcome | |||

| All cause mortality | 16.8 (14/83) | 22.2 (12/54) | 19 (26/137) |

| Semiobjective | 21.7 (18/83) | 44.4 (24/54) | 30.7 (42/137) |

| Subjective | 61.4 (51/83) | 33.3 (18/54) | 50.4 (69/137) |

| Type of intervention | |||

| Pharmacological | 56.6 (47/83) | 62.9 (34/54) | 59.1 (81/137) |

| Non-pharmacological | 44.6 (36/83) | 35.2 (20/54) | 40.9 (56/137) |

Of the included meta-analyses, 26 (19%) used ‘all cause mortality’ as an outcome; 42 (31%) were based on ‘semiobjective’ outcomes and 69 (50%) on a ‘subjective’ outcome. The type of intervention was pharmacological in 59% of the meta-analyses. There were significant differences in the type of outcome reported by publication type (χ2; 2df=11.15, p=0.004) but not in the type of intervention reported (χ2; 1df=0.54, p=0.46).

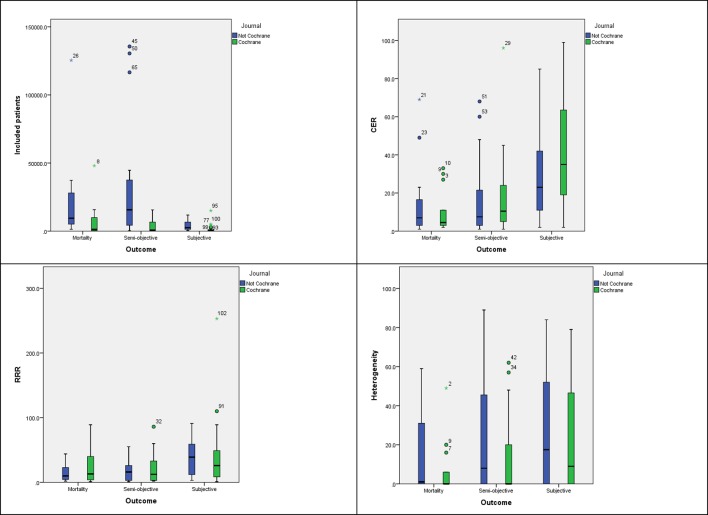

The descriptive analysis of the different parameter estimates (CER, RRR and I2) used in the calculation of the OIS showed considerable variation depending on the type of outcome (table 2 and figure 3).

Table 2.

Descriptive results for the statistical assumptions in the included meta-analyses

| CER | RRR* | Heterogeneity (I2) | Included patients | OIS estimated† | |

| All reviews (n=137) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.9 (26.1) | 28.2 31.5) | 20.4 (26.1) | 9426.0 (22 753.9) | 386 441.1 (1 645 397.1) |

| Cochrane reviews (n=83) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.0 (27.9) | 21.0 36.6) | 0.0 (25.5) | 586 (6245.8) | 2301.0 (1 422 086.6) |

| Non-Cochrane reviews (n=54) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.0 (21.7) | 20.0 20.6) | 14.5 (26.9) | 6566.5 (32 925.7) | 7299.5 (1 946 750.2) |

| All cause mortality (n=26) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.7 (16.5) | 20.3 22.1) | 10.9 (17.6) | 14 314.6 (25 880.1) | 499 090.7 (1 966 940.8) |

| Cochrane reviews (n=14) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.0 (11.2) | 25.5 27.3) | 6.7 (13.7) | 6902.5 (12 971.1) | 813 301.7 (2 678 677.7) |

| Non-Cochrane reviews (n=12) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.8 (21.4) | 14.3 12.6) | 15.7 (20.8) | 22 962.1 (34 232.8) | 132 511.2 (201 708.8) |

| Semiobjective (n=42) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 17.2 (20.9) | 19.0 18.7) | 18.8 (25.9) | 18 683.5 (33 125.7) | 828 450.9 (2 444 468.1) |

| Cochrane reviews (n=18) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 18.5 (10.5) | 21.7 24.0) | 12.8 (22.7) | 3384.8 (4762.7) | 536 616.8 (1 803 091.2) |

| Non-Cochrane reviews (n=24) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.3 20.0) | 16.9 13.7) | 23.3 (27.5) | 30 157.0 (40 233.9) | 1 047 326.5 (2 851 698.9) |

| Subjective (n=69) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.2 (27.1) | 36.8 (37.9) | 24.9 (28.1) | 1948.9 (2971.0) | 74 944.0 (406 792.0) |

| Cochrane reviews (n=51) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.6 (27.9) | 36.5 (41.6) | 23.5 (27.6) | 1173.0 (2244.3) | 78 688.6 (449 189.7) |

| Non-Cochrane reviews (n=18) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 28.5 (22.9) | 37.6 (25.3) | 28.9 (29.7) | 4147.3 (3683.7) | 64 334.2 (261 366.6) |

*For the calculation of this descriptive variable all the values were considered as positive.

†This estimation of the OIS was done under the conditions of the ‘scenario 2’ (heterogeneity=0, alpha 5%).

CER, control event rate; OIS, optimum information size; RRR, relative risk reduction.

Figure 3.

Systematic review characteristics stratified by source (Cochrane vs non-Cochrane) and type of outcome. CER, control event rate; RRR, relative risk reduction.

The number of included patients was higher in non-Cochrane reviews for all outcomes analysed (table 2). The CER for ‘all cause mortality’ had the lowest mean value and the distribution differed between outcome types. For RRR, the highest mean value and heterogeneity was observed for ‘subjective’ outcomes (table 2 and figure 3).

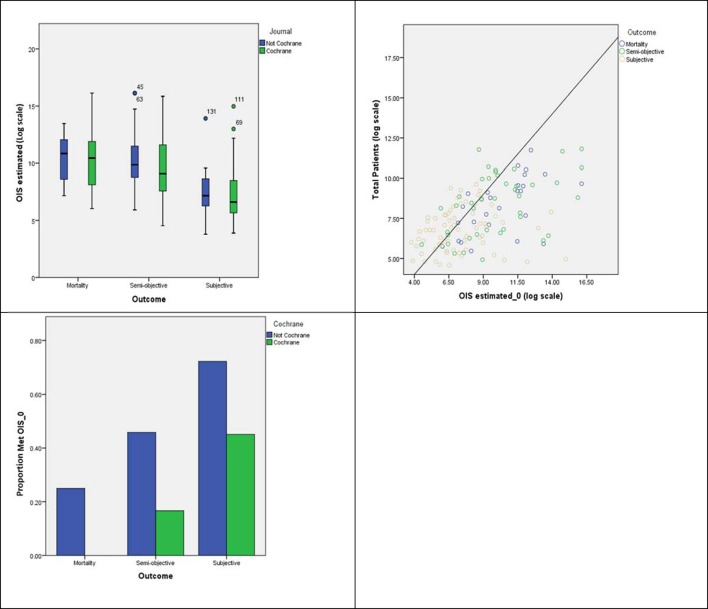

Meta-analyses that reached the OIS

Figure 4A presents the estimated OIS for each meta-analysis in the extreme scenario of no heterogeneity. All-cause mortality required the highest OIS for both types of reviews. However, this was only marginally higher than ‘semiobjective’ outcomes. For ‘subjective’ outcomes, OIS estimates are considerably smaller due to higher CERs and RRR. Figure 4B shows the number of meta-analyses that have achieved sample sizes equal or higher to the estimated OIS with more non-Cochrane reviews achieving this estimate (see figure 4C).

Figure 4.

OIS estimated considering best-case scenario (heterogeneity=0) by (A) type of outcome and source; y-axis is on the log scale, (B) related to the total number of patients included in each SR and (C) proportion of SRs achieving the OIS by type of outcome and source. OIS, optimum information size; SRs, systematic reviews.

Estimation of the OIS based on reported heterogeneity shows that the necessary sample was only reduced for Cochrane SR reporting subjective outcomes (table 3). Further increasing the level of heterogeneity (worst-case scenario: heterogeneity=Q3) did not substantially change the proportion of meta-analyses achieving the OIS.

Table 3.

Percentage of meta-analyses that achieve the OIS by heterogeneity (I2) level assumed

| % (n/N) | All cause mortality | Semiobjective | Subjective | ||||||

| Coch | Non-Coch | 95% CI difference | Coch | Non-Coch | 95% CI difference | Coch | Non-Coch | 95% CI difference | |

| OIS | (−0.074 to 0.571) |

(−0.043 to 0.499) |

(0.111 to 0.616) |

||||||

| Achieved | 0 | 25 | 11.1 | 37.5 | 31.4 | 72.2 | |||

| I2=reported | 0/14 | 3/12 | 2/18 | 9/24 | 16/51 | 13/18 | |||

| OIS | (−0.074 to 0.571) |

(−0.031 to 0.534) |

(−0.024 to 0.490) |

||||||

| Achieved | 0 | 25 | 16.6 | 45.8 | 45.1 | 72.2 | |||

| I2=0 | 0/14 | 3/12 | 3/18 | 11/24 | 23/51 | 13/18 | |||

| OIS | (−0.134 to 0.491) |

(−0.079 to 0.460) |

(0.027 to 0.553) |

||||||

| Achieved | 0 | 16.6 | 11.1 | 33.3 | 29.4 | 61.1 | |||

| I2=Q3 | 0/14 | 2/12 | 2/18 | 8/24 | 15/51 | 11/18 | |||

coch, Cochrane meta-analyses; non-Coch, non-Cochrane meta-analyses; OIS, optimum information size.

When using a more stringent estimate for the effect size (5% RRR) for ‘all cause mortality’, none of the identified meta-analyses had achieved the necessary sample size to meet the OIS (0/14 Cochrane and 0/12 non-Cochrane). Box presents five examples of meta-analyses reporting ‘all cause mortality’ as an illustration of SRs where the OIS has been reached and where it has not.

Box. Example of five meta-analyses with the ‘all cause mortality’ as the main outcome that do, or do not, achieve the optimum information size (OIS).

Meta-analysis that meet the OIS

Weng et al (Annals of Internal Medicine)25

This meta-analysis evaluated the use of a non-pharmacological intervention (non-invasive ventilation) to treat patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema including a total of 1369 patients with a control event rate (CER) of 23%, relative risk reduction (RRR) 27% and 0% heterogeneity. For this systematic review assuming a 0% heterogeneity, the OIS estimated was 1296 patients.

Gastric team (The Journal of the American Medical Association)26

This meta-analysis evaluated the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer including a total of 3781 patients with a CER 69%, RRR 9% and 24% heterogeneity reported by the meta-analysis. For this systematic review assuming a 0% heterogeneity, the OIS estimated was 1828 patients.

NSCLC meta-analysis (The Lancet)27

This meta-analysis evaluated the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with operable non-small cell lung cancer including a total of 8447 patients with a CER 49%, RRR 11% and 1% heterogeneity reported by the meta-analysis. For this systematic review assuming a 0% heterogeneity, the OIS estimated was 2686 patients.

Meta-analysis with a large number of included patients that not meet the OIS

Adam et al (Annals of Internal Medicine)28

This meta-analysis evaluated the use of warfarin versus new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism including a total of 14 143 patients with a CER of 2%, RRR 12% and 0% heterogeneity reported. For this systematic review assuming a 0% heterogeneity, the OIS estimated was 100 562 patients.

Rizos et al (The Journal of the American Medical Association)29

This meta-analysis evaluated the administration of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events including a total of 125 410 patients with a CER of 7%, RRR 4% and 1% heterogeneity reported. For this systematic review assuming a 0% heterogeneity, the OIS estimated was 255 912 patients.

Discussion

Our results show that there is wide variability in the range of values that impact on the OIS calculation: effect size (RRR), heterogeneity (I2) and CER, regardless of source (Cochrane or non-Cochrane). This variability is partially explained by the type of outcome (‘all cause mortality’, ‘semiobjective’ or ‘subjective’) evaluated.

OIS estimates could therefore be obtained from different types of outcomes, as previously proposed by Turner et al9 and Rhodes et al.11 To our knowledge, this is the first time that accounting for the type of outcome in the estimation of the OIS has been proposed. We also found that the type of outcome impacts on the range of heterogeneity observed and was particularly high for ‘subjective’ outcomes. One possible explanation for this is the higher number of smaller randomised controlled trials. Nevertheless, these differences were more marked in Cochrane reviews, while non-Cochrane reviews showed more similar levels of heterogeneity across all types of outcomes. The obtained results show that globally less than half of recent published meta-analysis in high-quality journals achieved the OIS and therefore do not have appropriate statistical power to draw firm conclusions.

As expected, the estimation of the OIS assuming different levels of heterogeneity, and alpha values, showed a strong correlation. Although we used specialist software for the estimation of the OIS (TSA V.0.9), it is possible to estimate this value using any software that allows sample size estimation if the heterogeneity level is assumed to be zero. Incorporation of heterogeneity can be done using a simple adjustment proposed by Wetterslev.5 This author proposes the use of an alternative index named the diversity (D2) statistic as opposed to the I2 factor. However, there is currently no consensus on what measure of heterogeneity to adopt for the OIS.4 14

Published meta-analyses that estimate optimal information size often use one or more statistical assumptions, such as a RRR of 10%, or the median RRR of trials with low risk of bias.15–17 Our analysis shows that the median of the RRR is 20% for all pooled reviews. However, because the distribution of RRR varies by outcome type, in some cases optimal information size is underestimated, while in others it is overestimated.

Limitations

There are several proposed statistics to define a ‘desirable sample size in terms of numbers of participants across all studies’.4 The OIS as described in this paper involves a relatively simple calculation, which if anything is likely to underestimate the information required to define whether firm evidence has been reached to draw robust conclusions4 14 Therefore, we used this definition of OIS as a measure to estimate what proportion of SRs meet this minimum requirement.

We have focused exclusively on the calculation of a single threshold to define when/if a minimum level of evidence has been collected. However, retrospective analyses of meta-analytical results are more commonly used to inform prospective studies. For example, to determine the size of a new trial to answer definitively a question around efficacy. The use of trial sequential methods has been proposed to identify early signals of effect with monitoring boundaries being defined by frequentist, semi-Bayesian and fully Bayesian methods.4 18 19 Although there is still considerable uncertainty about the estimates and the best method to use, empirical studies have provided examples to suggest these methods could help detect signals early (benefit, harm or futility).8 20 Of note, the identification of the sample size required in a new study or studies will depend on the method used in the meta-analysis.14

Reviews conducted by the Cochrane collaboration are considered to be higher quality21 22 and of greater methodological rigour than meta-analyses published in paper-based journals. Our study only included meta-analyses from the top five medical journals, and therefore our results may not be applicable to other meta-analyses published in other journals. Nevertheless, this would bias our results towards better evidence being evaluated to what is currently being generated. Also, our results do not generalise to network meta-analyses, which is an area of evidence synthesis that has grown rapidly.23 A recently published study demonstrated that substantial variation exists in such network-based meta-analysis,24 and the statistical methodology to estimate the OIS in these meta-analyses is less developed than for traditional meta-analysis, hence our exclusion of these studies.

Implications for researchers and methodologists

This study has shown that the type of outcome when estimating the OIS can be used as a proxy for defining the basic parameters (CER, RRR and I2) required to perform the calculation. Systematic reviewers can use these results to calculate an OIS value for their primary outcome independently of the confidence they have on the specific parameters obtained from their review. Therefore, we encourage reviewers to use the estimation of a sample size as a measure of the likely confidence in their results. Particularly as >50% of the primary outcomes in recent SRs appear to fall below this minimum requirement, pointing out the need for further evidence to reduce uncertainty.

Conclusions

Heterogeneity and effect size impact on the estimation of the OIS. It is however possible to estimate the OIS using traditional sample size estimation software and if necessary adjust for heterogeneity. Our results demonstrate that the type of outcome is relevant to the estimation of the OIS, as well as the heterogeneity and the CER and RRR. Currently less than half of published meta-analysis in high-quality journals have achieved the OIS, and therefore conclusions based on such results are subject to substantial uncertainty.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. We wish to thank Pol Escarpenter for his support to adapt the figures to the requested format of the journal.

Footnotes

Contributors: JMG-A and RP conceived and designed the study. JMG-A and NP extracted the data. JMG-A and RP analysed the data. JMG-A, RP, CB and CH interpreted the data. JMG-A and RP wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, revised the intellectual content and approved the version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All of the data used in this research are provided within this publication, its appendices and the publications referenced in the online supplementary appendices.

References

- 1.Pogue J, Yusuf S. Overcoming the limitations of current meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 1998;351:47–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08461-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pogue JM, Yusuf S. Cumulating evidence from randomized trials: utilizing sequential monitoring boundaries for cumulative meta-analysis. Control Clin Trials 1997;18:580–93. 10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brok J, Thorlund K, Gluud C, et al. Trial sequential analysis reveals insufficient information size and potentially false positive results in many meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:763–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins JP, Whitehead A, Simmonds M. Sequential methods for random-effects meta-analysis. Stat Med 2011;30:903–21. 10.1002/sim.4088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, et al. Estimating required information size by quantifying diversity in random-effects model meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:86 10.1186/1471-2288-9-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, et al. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:64–75. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner RM, Bird SM, Higgins JP. The impact of study size on meta-analyses: examination of underpowered studies in Cochrane reviews. PLoS One 2013;8:e59202 10.1371/journal.pone.0059202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imberger G, Thorlund K, Gluud C, et al. False-positive findings in Cochrane meta-analyses with and without application of trial sequential analysis: an empirical review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011890 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner RM, Davey J, Clarke MJ, et al. Predicting the extent of heterogeneity in meta-analysis, using empirical data from the cochrane database of systematic reviews. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:818–27. 10.1093/ije/dys041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorlund K, Engstrøm J, Wetterslev J. User manual for trial sequential analysis (TSA). Trial Unit Available Internet 2011. (accessed 11 Jun 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhodes KM, Turner RM, Higgins JP. Empirical evidence about inconsistency among studies in a pair-wise meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2016;7:346–70. 10.1002/jrsm.1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Glasziou PP, et al. New treatments compared to established treatments in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:MR000024 10.1002/14651858.MR000024.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden JA, Tomlinson G, Ni A, et al. Approaches to estimate and present baseline risks considerations for cochrane reviews evidence-informed practice integration of : 19th cochrane colloquium madrid, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulinskaya E, Wood J. Trial sequential methods for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:212–20. 10.1002/jrsm.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imberger G, Orr A, Thorlund K, et al. Does anaesthesia with nitrous oxide affect mortality or cardiovascular morbidity? A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Br J Anaesth 2014;112:410–26. 10.1093/bja/aet416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bangalore S, Kumar S, Wetterslev J, et al. Angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of myocardial infarction: meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 147 020 patients from randomised trials. BMJ 2011;342:d2234 10.1136/bmj.d2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afshari A, Wetterslev J, Brok J, et al. Antithrombin III in critically ill patients: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ 2007;335:1248–51. 10.1136/bmj.39398.682500.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wetterslev J, Jakobsen JC, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis in systematic reviews with meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:39 10.1186/s12874-017-0315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spence GT, Steinsaltz D, Fanshawe TR. A Bayesian approach to sequential meta-analysis. Stat Med 2016;35:5356–75. 10.1002/sim.7052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AlBalawi Z, McAlister FA, Thorlund K, et al. Random error in cardiovascular meta-analyses: how common are false positive and false negative results? Int J Cardiol 2013;168:1102–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remschmidt C, Wichmann O, Harder T. Methodological quality of systematic reviews on influenza vaccination. Vaccine 2014;32:1678–84. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Windsor B, Popovich I, Jordan V, et al. Methodological quality of systematic reviews in subfertility: a comparison of cochrane and non-cochrane systematic reviews in assisted reproductive technologies. Hum Reprod 2012;27:3460–6. 10.1093/humrep/des342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutton B, Salanti G, Chaimani A, et al. The quality of reporting methods and results in network meta-analyses: an overview of reviews and suggestions for improvement. PLoS One 2014;9:e92508 10.1371/journal.pone.0092508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers JD, Naci H, Wouters OJ, et al. An assessment of the methodological quality of published network meta-analyses: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121715 10.1371/journal.pone.0121715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weng CL, Zhao YT, Liu QH, et al. Meta-analysis: noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:590–600. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;303:1729–37. 10.1001/jama.2010.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arriagada R, Auperin A, Burdett S, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without postoperative radiotherapy, in operable non-small-cell lung cancer: two meta-analyses of individual patient data. Lancet 2010;375:1267–77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60059-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adam SS, McDuffie JR, Ortel TL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:796–807. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizos EC, Ntzani EE, Bika E, et al. Association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;308:1024–33. 10.1001/2012.jama.11374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.