Abstract

Introduction

Patients with complex care needs (PCCNs) often suffer from combinations of multiple chronic conditions, mental health problems, drug interactions and social vulnerability, which can lead to healthcare services overuse, underuse or misuse. Typically, PCCNs face interactional issues and unmet decisional needs regarding possible options in a cascade of interrelated decisions involving different stakeholders (themselves, their families, their caregivers, their healthcare practitioners). Gaps in knowledge, values clarification and social support in situations where options need to be deliberated hamper effective decision support interventions. This review aims to (1) assess decisional needs of PCCNs from the perspective of stakeholders, (2) build a taxonomy of these decisional needs and (3) prioritise decisional needs with knowledge users (clinicians, patients and managers).

Methods and analysis

This review will be based on the interprofessional shared decision making (IP-SDM) model and the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. Applying a participatory research approach, we will identify potentially relevant studies through a comprehensive literature search; select relevant ones using eligibility criteria inspired from our previous scoping review on PCCNs; appraise quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; conduct a three-step synthesis (sequential exploratory mixed methods design) to build taxonomy of key decisional needs; and integrate these results with those of a parallel PCCNs’ qualitative decisional need assessment (semistructured interviews and focus group with stakeholders).

Ethics and dissemination

This systematic review, together with the qualitative study (approved by the Centre Intégré Universitaire de Santé et Service Sociaux du Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean ethical committee), will produce a working taxonomy of key decisional needs (ontological contribution), to inform the subsequent user-centred design of a support tool for addressing PCCNs’ decisional needs (practical contribution). We will adapt the IP-SDM model, normally dealing with a single decision, for PCCNs who experience cascade of decisions involving different stakeholders (theoretical contribution). Knowledge users will facilitate dissemination of the results in the Canadian primary care network.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42015020558.

Keywords: patients with complex care needs, shared decision making, interprofessional care, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This work will be conducted with a participatory research approach involving multiple knowledge users’, including patients’ perspectives.

Large team governance can be an issue; thus, an executive task force will carry out the review.

The studies heterogeneity challenge will be raised by using an innovative mixed methods design three-step synthesis to build a taxonomy presenting various key decisional needs configuration.

Introduction

Rationale for the review

Community-based primary healthcare (hereafter, primary care) plays a key role regarding situations of complex care needs.1–3 Patients with complex care needs (PCCNs) often suffer from combinations of multiple chronic conditions, mental health problems, drug interactions and social vulnerability, which can lead to healthcare services overuse, underuse or misuse.1 4 5 However, this does not fully capture the complex care needs experience that encompasses individual (patient and practitioner), interpersonal (patient-practitioner or interprofessional (IP)), organisational (eg, resources), and sociocultural characteristics (eg, values).4 6–8 Typically, PCCNs face interactional issues related to personal uncertainty or disagreements regarding possible options (decisional conflict) and unmet decisional needs (eg, knowledge acquisition, clarification of values and preferences, support, and resources). The complexity of decision making could be exacerbated by a cascade of interrelated decisions involving different stakeholders (PCCNs, their families, their caregivers, their healthcare practitioners, etc). Gaps in knowledge, values clarification and social support in these situations where multiple options need to be deliberated (decisional needs) hamper decision support interventions.

In a quality improvement process, a group of health and social primary care practitioners, patients and researchers from Practice Based Research Networks (PBRNs) identified the necessity to better understand PCCNs’ decisional needs. Team members contributed to a pilot project that sought to identify characteristics of PCCNs and possible support interventions.9 10 A case series9 and a scoping review10 revealed that IP coordination of care and lack of stakeholders’ agreement are two major issues affecting this population. It is necessary to better understand the decisional needs of PCCNs associated with mismatched knowledge, expectations, personal values and social support related to a variety of personal, sociocultural and clinical characteristics. Three individual evaluation tools of complex care needs11–13 and one study about patient preference in the context of multimorbidity were identified.14 15 In the literature, we found no tool to facilitate shared decision making (SDM) between PCCNs, their families and caregivers, and healthcare providers. Thus, our target population, PCCNs, may benefit from a decisional needs assessment to inform the design of an IP-SDM tool that accounts for their knowledge, values and preferences.16

IP-SDM model

SDM is a process where one patient and one health professional work together to make a healthcare choice; it is essential for informed consent and patient-centred care.17–22 Industrialised countries such as Australia,23 UK24 and USA25 are currently implementing large SDM initiatives. SDM is an effective decision-making process when careful deliberation is needed to address uncertainties inherent to evidence-based medicine, and to weigh the risks and benefits of patients’ healthcare choices (based on their values and preferences). Many factors may influence the choices individuals make and the roles they attribute to others and to themselves in the context of IP care,26–29 which justifies framing this review with the IP-SDM model.30

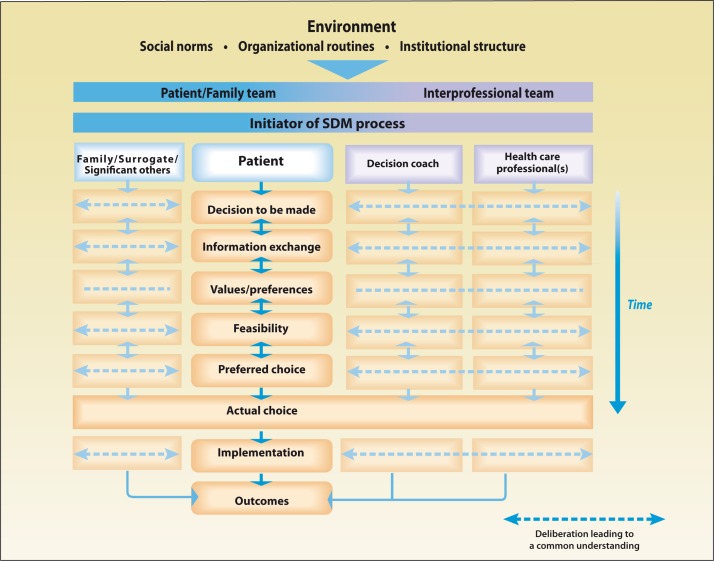

The IP-SDM model extends the SDM beyond the patient-health professional dyad to IP teams.30–32 In addition to its IP component, this model proposes to include family members and potential caregivers in a patient-centred process (figure 1). This model aims to stimulate deliberation and reach a common understanding among patients, family/surrogate/significant others, decision coaches and healthcare professionals. The IP-SDM model follows a patient-centred step-by-step process: (1) choose a decision to make and explore related options; (2) exchange information; (3) clarify values and preferences; (4) assess the feasibility of the decision; (5) choose the preferred decision option; (6) implement the decision; (7) assess the outcome. Based on the IP-SDM model, interventions have been developed for specific decision-making situations. For example, a study is currently under way to scale up and evaluate the implementation of IP-SDM intervention for frails elderly clients or their caregivers facing a decision about staying at home or moving elsewhere.33 34 The IP-SDM also takes into account the environmental complexity in which the SDM takes place (sociocultural norm, organisational routines and institutional structure). This model is particularly relevant to help IP teams respond to decisional needs of PCCNs as it helps the stakeholders reach informed value-based decisions.30 31 35 Typically, the IP-SDM is used for one decision. We will be the first team to adapt this model for PCCNs who experience complex interrelated decisions involving different stakeholders with various opinions.

Figure 1.

The interprofessional shared decision making (IP-SDM) model was designed to broaden the perspective of SDM beyond the patient–practitioner dyad and include IP teams. For more details on the IP-SDM model, consult the following website: http://www.decision.chaire.fmed.ulaval.ca/en/research/projects/interprofessional-approaches/.

Decisional needs assessment

A decisional need is usually derived from a needs assessment that addresses or focuses on a situation where multiple options need to be deliberated. Assessing decisional needs is needed in order to elaborate effective decision support, even more so when an IP team is required to provide decision support to a patient. A decisional needs assessment is particularly relevant for PCCNs, such as prioritising a cascade of complex decisions that involve multiple stakeholders. Decision support interventions address stakeholders’ decisional needs (decisional conflict, lack of knowledge and information exchange, values, expectation and preferences clarification, support and resource). Indeed, unmet decisional needs affects the decision quality (eg, uninformed, incongruent with values and unsupported socially). This in turn may affect behaviour (eg, uptake and maintenance of the chosen option), lead to negative emotions (eg, decision regret) and impact healthcare use (eg, overuse, underuse and misuse). The Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF) informs the conduct of the decisional needs assessment.36 37

The decisional needs assessment for PCCNs will answer the following questions: What are the types of decisions have to make complex care needs situations? Which decisions are most frequent? Which decisions are the most difficult to make and why? How these decisions are interrelated? Who are the stakeholders involved in the decision? What is needed to better support regarding the IP-SDM process (eg, information, values clarification, social support or else)? What is currently being done? What are the barriers and facilitators for applying this decision support? Several strategies could be mobilised to assess decisional needs of a population.16 38 One of them consists to review the existing information (ie, previous studies).16

Review question and objectives

Our overall review question is: What are, from the perspective of stakeholders, the key decisional needs of PCCNs? In line with the knowledge translation cycle,39 the purpose of our systematic review is to provide the needed groundwork to assess decisional needs of PCCNs. With a task force and a multidisciplinary team including researchers and knowledge users in community-based primary healthcare (see table 1), this review aims to:

Assess decisional needs of PCCNs from the perspective of stakeholders;

Build a taxonomy of these decisional needs;

Prioritise decisional needs with knowledges users (clinicians, patients, managers).

Table 1.

Multidisciplinary expertise of the research team and collaborators

| Expertise | Names* | n |

| Home healthcare | Beaulieu M-C; Duong S; Kremer B; Poitras M-E | 4 |

| Interprofessional/integrated care | Beaulieu M-C; Bujold M; Couturier Y; Haggerty J; Légaré F; Poitras M-E; Vedel I | 7 |

| Knowledge transfer and participatory research | Bigras M; Boulet A; Bujold M; Bush PL; Duong S; Giguere A; Grad R; Goulet S; Granikov V; Haggerty J; Kremer B; Kröger E; Légaré F; Lussier M-T; Martello C; Pluye P; Pratt R; McLauchlin L R; Samson I; Senn N; Tsujimoto M; Ventelou B; Vedel I; Wensing M | 24 |

| Patients with complex care needs | Bigras M; Boulet A; Bujold M; Couturier Y; Débarges B; Duong S; Goulet S; Grad R; Granikov V; Hudon C; Kremer B; Kröger E; Lebouché B; Loignon C; Lussier M-T; McLauchlin LR; Martello C; Poitras M-E; Pluye P; Pratt R; Rosenberg E; Samson I; Senn N; Ventelou B; Tsujimoto M; Vedel I; Wensing M | 26 |

| Patient and partner engagement | Bujold M; Bush P L; Débarges B; Granikov V; Loignon C; Pluye P; Poitras M-E; Samson I | 8 |

| Populations in situations of vulnerability | Couturier Y; Giguere A; Hudon C; Loignon C; Lebouché B; Kröger E; Rosenberg E; Tsujimoto M; Samson I; Ventelou B | 10 |

| Shared decision-making | Bujold M; Légaré F; Haggerty J; Hudon C; Giguère A; Lussier M-T; Pluye P; Poitras M-E; Rosenberg E; Senn N; Wensing M | 11 |

| Systematic mixed studies reviews | Bujold M; Bush PL; El Sherif R; Gore G; Kröger E; Lebouché B; Légaré F; Pluye P; Rihoux B; Rosenberg E; Tang D; Vedel I; Wensing M | 13 |

| Tool development and validation | Bujold M; El Sherif R; Grad R; Giguère A; Lussier M-T; Légaré F; Li Tang D; Pluye P; Pratt R; Senn N; Wensing M | 11 |

| Profession | Names* | n |

| Biology | Bujold M; Débarges B; Giguère A | 3 |

| Computer science | Tang D | 1 |

| Epidemiology | Haggerty J; El Sherif R; Kröger E | 3 |

| Librarianship | Gore G; Granikov V | 2 |

| Medicine | Bigras M; Beaulieu M-C; Beaulieu M D; Goulet S; Grad R; Hersson F; Hudon C; Lebouché B; Légaré F; Lussier M-T; Martello C; McLauchlin L.R; Pluye P; Pratt R; Rosenberg E; Samson I; Senn N; Ventelou B; Wensing M | 19 |

| Nursing | Boulet A; Poitras M-E | 2 |

| Occupational/physical therapy | Bush P L | 1 |

| Pharmacy | Duong S; Kröger E | 2 |

| Public health | Légaré F; Loignon C; Pluye P; Vedel I; Wensing M | 5 |

| Social work and social sciences | Bujold M; Couturier Y; Gagnon J; Hudon C; Loignon C; Rihoux B | 6 |

*Alphabetical order.

Methods

This review will use a multipronged approach. First, we will conduct a systematic mixed studies review (including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies).40 Mixed studies reviews provide a rich and highly practical understanding of complex health issues.41–46 Second, we will use an organisational participatory research approach, involving researchers and knowledge users (clinicians, patients, managers), to determine key decisional needs.

We will, thus, blend research with action using a number of iterative cycles, thereby producing knowledge that can inform healthcare practices.47–50 Organisational participatory research consists of doing research with patients and practitioners, rather than on them; it is a strategy for organisational change and practice improvement.50–54 It also supports the idea of producing knowledge that respond to the needs and perspectives of the knowledge users rather than producing knowledge to which they need to adapt. This approach is suitable for this review as the pilot project emerged from practice. A multidisciplinary team blending scientific and practical knowledge is necessary to achieve our objectives (table 1). Team members are researchers with various expertise, and knowledge users (directors and clinicians, patients and managers) of the four Quebec network of Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRN)55 and the Quebec SPOR SUPPORT Unit (SPOR standing for Strategy for Patient Oriented Research). In partnership with knowledge users, we will systematically search, identify, select, appraise, and synthesise qualitative and quantitative evidence. An executive task force will lead the review and mobilise the participatory review team (knowledge users, co-researchers, patient experts and international experts).

Information sources and search strategy

Building on our previous work,9 10 the concept map and the search strategy (see box) was written and tested in collaboration with specialised librarians. Based on the scoping review,9 we anticipate retrieving about 4500 potentially relevant database records (authors, title, source, abstract) in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCOhost) and Social Sciences Citation Index. No search date limit will be used. In addition, our librarians will provide guidance in searching the grey literature using Google Scholar, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science and specialised websites. After the selection stage, other potentially relevant records will be sought by tracking citations of included studies using Scopus, up to saturation (no additional studies found). Our team members, including knowledge users, will be emailed to request additional records or bibliographies.

Box. Search Strategy in Medline: concept map (Concepts 1 and 2 and 3 and 4).

Concept 1: Patients with complex care needs

(complex adj4 (problem* or issue* or patient? or need? or care or existence? or experience? or live? or realit* or journey? or situation?)).ti,ab,kf.

complex case?.mp.

(complexity adj4 (clinical or patient? or science or theory)).mp.

((high-effort or burden or complicated or demanding) adj patient?).mp.

exp Vulnerable Populations/

poverty/or poverty areas/or unemployment/or homeless persons/or homeless youth/or exp *aged/or frail elderly/or exp ‘Emigrants and Immigrants’/or minority groups/or exp disabled persons/or drug users/or medically uninsured/or refugees/or exp culture/

poverty or disadvantaged or underserved or under served or indigen* or tribe? or tribal or native? or aboriginal* or low income* or unemploy* or underemploy* or under employ* or homeless* or street people or street person? or (social* adj (isolat* or stigma*)) or inequalit* or uninsured or underinsured or unader insured or uneducated or low* educat* or poor* educat* or illitera* or (low adj2 litera*) or functional* impair* or disabled or disabilit* or handicap* or physical* challenge* or mental* challenge* or ((drug or substance) adj (abuse* or addict* or dependen* or habit? or ‘use*")) or minorit* or emigra* or immigra* or migra* or foreigner* or refugee*).ti,ab,kf.

(vulnerab* or aged or elderly or frail* or senior?).ti.

((frail* or vulnerab* or at risk or high risk or low function or dependent) adj2 (older or elder* or senior* or patient*)).ti,ab,kf.

(cald or (cultural* adj3 divers*) or multicultur* or intercultur* or (patient* adj cultur*) or (cultural* adj3 (background* or differen*)) or ethnocultural* or (cultural* adj (aware* or competen* or appropriate* or relevan* or safe* or train*))).ti,ab,kf.

(vulnerab* adj (patient? or population? or social*)).ti,ab,kf.

sensitive population?.ti,ab,kf.

((Frequen* or high) adj2 (attend* or consult*)).ti,ab,kf.

(‘frequent visit*’ or ‘frequent flyer*’ or ‘heavy user*’ or ‘repeat use’).ti,ab,kf.

((((frequen* or high) adj2 (user* or utili*)) or ‘high use’ or ‘frequent use’) adj3 (patient* or hospital* or emergency or ED or services)).ti,ab,kf.

‘revolving door’.ti,ab,kf.

‘frequent hospitali#ation*".ti,ab,kf.

((preventable or avoidable) adj2 (utili* or visit* or hospitali* or consultation*)).ti,ab,kf.

(high adj2 risk adj3 hospitali#ation*).ti,ab,kf.

(‘frequent use*’ or ‘frequent utilis*’ or ‘high use*’ or ‘high utili*").kf.

mental disorders/or mental health/

((mental* or psychiatric) adj (health* or disorder* or disease* or ill*)).ti.

comorbidity/

((comorbidit* or multi* morbidit* or multimorbidit*).ti,ab,kf.

exp polypharmacy/

exp drug interactions/

exp ‘Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions’/

((adverse adj (effect? or event? or reaction?)).ti.

((multi* adj (therap* or treatment* or drug? or medication?)) or polypharmac*).ti,ab,kf.

drug* interact*.ti,ab,kf.

exp complementary therapies/

exp herbal medicine/

((alternative* or complementar* or folk* or herbal or integrat* or natural or non-prescription or over the counter or traditional) adj2 (health* or medication* or medicine* or product* or remedy or remedies or therap* or treatment*)).ti,ab,kf.

34 or/1–33

Concept 2: Primary healthcare

exp Primary Health CareHealthcare/

exp Primary Care Nursing/

exp General Practice/

Community Health Services/

exp Community Pharmacy Services/

Community Mental Health Services/

Community Health Nursing/

Social Work/

General Practitioners/

Physicians, Family/

Physicians, Primary Care/

Social Workers/

(primary care or primary health carehealthcare or primary healthcare or community nursing or family practice or general practice or family medicine or family physician* or family practitioner* or family doctor* or general physician* or general practitioner* or community based medicine or community mental health service* or community mental health nursing or community health nursing or community health service* or community pharmac* or primary practice or primary practitioner* or psychologist* or social service* or social work* or (communit$3three adj5 nurse?)).ti,ab,kf.

or/35–47

Concept 3: Interpersonal relations

exp Interpersonal Relations/

exp patient care team/

(exp nurses/or exp physicians/or pharmacists/or social workers/or (nurse* or pharmacist* or physician* or psychologist* or social worker* or clinician* or doctor* or practitioner* or gps or health carehealth care professional* or healthcare professional* or health carehealth care provider* or healthcare provider* or ((primary care or primary healthcare or primary health carehealth care) adj provider*) or resident*).ti.) and (exp patients/or caregivers/or exp Family/or (patient* or consumer* or people* or carer? or caregiver? or family or families).ti.)

exp consumer participation/or ((patient* or consumer*) adj6 (interaction* or empower* or engagement* or involvement* or involving* or participation* or participating*)).ti,ab,kf.

(exp patients/or (patient* or inpatient* or outpatient* or hospitali#ed or institutionali#ed or consumer* or people*).ti.) and (caregivers/or exp Family/or (carer* or caregiver* or family or families).ti.)

(collaborat* or team*).ti,ab,kf.

(interprofessional* or inter professional* or interdisciplinar* or inter disciplin* or interoccupation* or inter occupation* or multiprofessional* or multi professional* or multidisciplin* or multi disciplin* or multioccupation* or multi occupation*).ti,ab,kf.

(interpersonal* or shared care).ti,ab,kf.

or/49–56

Concept 4: Decisional needs

(decision* or decided or decides or deciding or choice*).ti,ab,kf.

exp decision making/or informed consent/or exp problem solving/or (exp patient preference/and patient education as topic/)

((patient* adj3 (voice* or perspective*)) or preference* or deliberation* or navigat* or accommodation* or accord? or agree* or arrangement or compromise or conciliation or counterbalance or counterpoise or equipoise or mediation or negotia* or poise or prioriti?ation or prioriti?e* or prioriti?ing or reconciliation).ti,ab,kf.

(regret* or blame* or uncertaint* or disagreement or disconcerted or faithless or dissension or dissent* or distrust* or indecision or indecisive or refusal or trustless or undecided or untrustworthy or untrusting or mistrust*).ti,ab,kf.

or/58–61

34 and 48 and 57 and 62

Limit 63 to (English or French or Spanish)

Eligibility criteria and identification of potentially relevant studies

Eligibility criteria will be based on the previous scoping reviews on PCCNs10 with a focus on interactional and decisional issues. A study will be included if it is a French, English or Spanish language empirical study about:

PCCNs (any study dealing directly or indirectly with PCCNs or a population with at least one of the following characteristics: multiple chronic conditions; mental health issues; drug interactions; social vulnerability; or healthcare services overuse, underuse and misuse);

primary healthcare setting (any study dealing directly with primary healthcare setting or indirectly, eg, links between primary care and secondary or tertiary care setting);

interpersonal relationships (reciprocal interaction of two or more persons, eg, IP, or professional–patient, patient–family or professional–family);

decisional needs (frequent or difficult decisions regarding situations where multiple options are possible, factors affecting the decision-making process, decisional conflict, support and resources used or needed to improve decision quality, barriers and facilitators to using decision supports).

We expect to identify about 300 potentially relevant studies. We will use EndNote (reference management software) to remove duplicates and store records with indexing terms. For each record, two reviewers will independently assign codes according to our eligibility criteria using specialised software (DistillerSR). For each code, we will measure the agreement between reviewers (kappa).56 57 When reviewers disagree, the record will be included in the following selection process.

Selection of relevant studies (coding full-text documents)

We anticipate including 150 relevant studies as follows. The two reviewers will independently code each full-text paper identified in the previous step. As with identification, inter-reviewer agreement will be measured. Disagreements that are not resolved easily will be referred to a third party.58

Critical appraisal of included studies

Critical appraisal is a core component of systematic reviews.39 58 It provides a rationale to break down the synthesis of included studies by level of quality. We will use the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT),42 59 60 a unique validated tool for critically appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies in systematic mixed studies reviews.61 Using the 2011 version of the MMAT62 appraisal form and user manual, two reviewers will independently appraise included studies. As with selection, inter-reviewer agreement will be measured, and disagreements resolved.

Synthesis design

Included studies will be described in a summary table.58 61 63 Then, guided by a sequential mixed methods design,40 46 64 we will conduct a three-step synthesis.

Step 1: Objective 1—assess decisional needs of PCCNs from the perspective of stakeholders

For each included study, two reviewers will independently list decisional needs using a deductive/inductive qualitative thematic analysis with specialised software (NVivo 11).65–68 For each decisional need (eg, goal setting), type of stakeholder (eg, patient), the facilitators (eg, interpreter) and barriers (eg, language) influencing the decision will be listed, including stakeholders’ information needs (eg, list of option with their, respective, potential benefits and harms), values, preferences and sources of support.

Data extraction

A hybrid thematic analysis (deductive/inductive) will be used. All articles will be coded using predefined themes (codebook) derived from the IP-SDM model and the ODSF (framework for decisional needs assessment),38 as well as themes suggested by the data; thus, creating an inventory of decisional needs and their facilitators and barriers. All team members, including knowledge users, will have the opportunity to discuss and refine the code book during online workshops with the executive task force. Consistency and rigour will be ensured via a process of combining interpretations and dialogues.67 69 Executive task force team members will examine the inventory and written interpretations, and ask the reviewers to explain strengths and limitations of their interpretations (trustworthiness) and to suggest alternative interpretations.

A comparative analysis will be conducted to explore similarities/differences among stakeholders’ perspectives. Using NVivo 11, the qualitative data (excerpt of the selected studies) will be assigned to the following ‘type of stakeholder’ attribute value: patients, family, caregivers, practitioners, others. This will allow us, for example, to compare the perceptions that patients have of their decisional needs with those of practitioners. We will also assign other categories of attributes (eg, types of practitioners) to the data.

Data synthesis

A summary table of the analysis will be made by systematically noting the following for all decisional needs: label, definition, type of stakeholder, facilitators that simplify patients’ decisions, barriers that make decisions difficult with patients, key excerpts of articles broken down by decisional need (illustrative examples). The summary table will be posted on our review blog, and the team members (researchers and knowledge users) will provide feedback. Given the feedback, some of the decisional needs will be revised, and modifications will be discussed. Then, a harmonisation of themes will be conducted.70 For each term, the usage will be confirmed in reference to documents on decision making (distinguishing accurate from improper usage), and accurate usages will be adopted to avoid ambiguity.

Step 2: Objective 2—build a taxonomy of decisional needs

The Configurational Comparative Method (CCM) is a case-based analysis useful for building taxonomies.71 72 For this review, each included study will be a case. Using CCM, we will determine commonalities in the relationships between decisional needs, their facilitators and barriers. We will use CCM to test relationships between decision-related variables using Boolean algebra. The main steps of a CCM analysis are as follows: defining conditions and outcomes, extracting data, preparing a truth table (cases in row, and conditions and outcome in columns), performing data minimisation with specialised software (QCA-GUI), and interpreting results. CCM is appropriate for two reasons: the theory-driven approach (IP-SDM) and the heterogeneity of study designs. The conditions and outcomes will be determined following the qualitative synthesis of the included studies.

Data extraction

We will use a data extraction form to ensure a systematic process.73 Then, we will conduct a quantitative content analysis.74 The codebook will contain categories listed in step 1 (deductive coding), and will be tested by two coders using a random sample of 10% of our cases (studies). For each case, the two coders will independently assign text excerpts to codes (variables and values). This will produce a table of raw data. Intercoder agreement will be measured (kappa). Disagreements that are not resolved easily will be referred to a third party. For each code with less than substantial agreement (kappa <0.61),57 the codebook will be revised (label, definition and key extracts) and an additional random sample of cases (10%) will be coded.

Data synthesis

Data will be discussed by executive task force members to produce a table of binary variables with cases in rows and variables in columns. Then, we will conduct the CCM,71 72 group similar cases in sets and produce a table of configurations of decisional needs (sets in rows, variables in columns). Results will be interpreted by going back and forth between configurations and cases. The configurations will allow us to ‘pose more focused questions’ on the cases.72 Configurations of decisional needs and interpretations will be reviewed. The configurations of decisional needs will be posted on the blog, and feedback provided by the team members. Discrepancies that are not resolved easily will be referred to a third party. The synthesis will produce a comprehensive taxonomy of decisional needs for PCCNs.

Step 3: Objective 3—determine key decisional needs

The taxonomy will be discussed in half-day workshops with team members, and a penultimate taxonomy will be posted on the blog. Then, the importance of decisional needs (taxonomy elements) will be rated by the team members with a blog-embedded web questionnaire and a five-item Likert scale (from ‘not important at all’ to ‘extremely important’). Discrepancies (eg, a need with a variety of ratings from low to high importance) that are not resolved easily will be referred to a third party. This will produce a taxonomy of key decisional needs, facilitators and barriers.

The taxonomy will be compared and integrated with the results of a parallel qualitative decisional need assessment of PCCNs that is part of the provincial ‘Demonstration project’ of the Quebec SPOR SUPPORT Unit funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Quebec Ministry of Health and the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS). In this parallel qualitative study, conducted by coauthors of this review, semistructured interviews and focus group will be done with patients/relatives, health and social primary care practitioners and decision makers to empirically assess decisional needs of PCCNs. This qualitative study will involve four expert patients, including one who is participating in all stages of the systematic review. The qualitative decisional need assessment and this systematic review will be done concurrently to validate emerging decisional needs. This will give a deeper and broader understanding to better inform the subsequent user-centred design of an IP-SDM support tool.

Ethics and dissemination

PCCNs are associated with unmet healthcare needs, overuse, underuse or misuse of healthcare services, low quality of care and increased costs of health systems.75–77 Given the ageing population and rising rates of chronic disease, the number of PCCNs is growing.2 5 78 This systematic review, together with the parallel qualitative study, will contribute to the assessment of decisional needs of PCCNs from the perspective of stakeholders (substantive contribution). The qualitative study was approved by the scientific and ethical committee of the ‘Centre Intégré Universitaire de Santé et Service Sociaux du Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean’ (Integrated University Centre of Health and Social Services). The ultimate result of this work will be a working taxonomy of key decisional needs of PCCNs (ontological contribution). We will adapt the IP-SDM model, normally dealing with a single decision, for PCCNs who experience a cascade of complex interrelated decisions involving different stakeholders with various opinions (theoretical contribution). The taxonomy of key decisional needs will inform the subsequent user-centred design an IP-SDM support tool (practical contribution). This tool will frame PCCNs’ decisional needs, help stakeholders prioritise decisions and understand options and PCCNs’ goals, and facilitate finding a common ground crucial for improving patient–practitioner and IP interactions, quality of decisions and care.79

This systematic review will help bridge two knowledge gaps: on the one hand, the majority of intervention studies address simple care needs rather than complex ones; on the other hand, current systematic reviews typically focus on one condition and one homogeneous population.80–84 The studies’ heterogeneity challenge will be addressed by using an innovative mixed methods design three-step synthesis to build a taxonomy presenting various key decisional needs’ configurations.

Previous studies showed that PCCNs are typically facing interactional issues, which justifies framing this proposal within the IP-SDM model. Evidence shows that SDM support tools improve patient–practitioner interactions and decision quality, and reduce ineffective care.85 86 However, we know of no decision support tool that could facilitate SDM between PCCNs and multiple professionals. One contribution of this review will be to enhance decision support for these patients.

As with all systematic reviews, due to publication bias, this work will be biased towards positive results and runs a risk of conflating predetermined outcomes that were identified by authors of the studies with the decisional needs of PCCNs. This limitation will be reduced by validating the results with the knowledge users (clinicians, patients and managers) and the qualitative results of the Demonstration project of the Quebec SPOR SUPPORT Unit.

This review emerged from two Quebec PBRN pilot work addresses an important issue for knowledges users and is a priority of the Quebec Ministry of Health.87 In line with CIHR priorities (http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/193.html), patients’ perspectives will be included in this review given our organisational participatory research approach and our user-centred design. Diffusion will involve raising general awareness about our results through conference presentations and publications. Dissemination, a more active and targeted strategy, will consist of reaching other knowledge users through websites, listservs and peer networks through Quebec PBRNs and the Canadian SPOR networks.

Systematic review status

The review is currently in the protocol and search strategy updating phase. We are testing the search strategy in Ovid MEDLINE (2 February 2017). We expect to complete the selection of relevant studies in 2017 and design the first version of the IP-SDM support tool in 2018.

Key terms

Knowledge users: The directors and the members (clinicians, patients, managers) of the four Quebec PBRNs and the Quebec SPOR SUPPORT Unit.

Team members: All coauthors (knowledge users and researchers) and collaborators (see Acknowledgements).

Primary care: Community-based primary healthcare.

Stakeholders: Patients with complex care needs, their families, their caregivers, their healthcare practitioners or any other people involved in decision-making related to their complex care needs (eg, surrogate, significant others, case manager, decision coach, navigator, mediator, interpreter).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this protocol was supported by the Quebec SPOR SUPPORT Unit. Pierre Pluye holds a salary award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS). Authors gratefully acknowledge and the following collaborators: Magali Bigras and Alain Boulet, Centre de santé et de services sociaux de Gatineau, Canada; Lynn R. McLauchlin, St. Mary’s Hospital Center, Montreal, Canada; Silvia Duong, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Canada; and Fanny Hersson, Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Canada).

Footnotes

Contributors: PP, FL and MB conceived and designed the review with input from all team members. MB drafted the manuscript. All authors (MB, PP, FL, JH, GG, RES, M-EP, M-CB, M-DB, PLB, YC, BD, JG, AG, RG, VG, SG, CH, BK, EK, IK, BL, CL, M-TL, CM, QN, RP, BR, ER, IS, NS, DT, MT, IV, BV, MW) read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript and will participate to workshops. Executive task force are (MB, PP, RES). Team members are (1) knowledge users (JH, M-CB, M-DB, BD, BK, IK, M-TL, CM, ER, IS, NS, RG, SG); (2) co-researchers (FL, GG, M-EP, PLB, YC, JG, AG, VG, CH, EK, BL, CL, QN, RP, BR, DT, MT, IV, BV, MW, BPL, CY, GA); (3) international experts (RB, RP, NS, MT, BV, MW). The executive team is doing the bulk of the work. GG participated intensively in the systematic search strategy planning and operationalisation. The authors of this systematic review who are also involved in the qualitative decisional need assessment study are M-EP, FL (co-leaders), MB, CH, PP (co-researchers) and BD, M-DB (knowledge users).

Funding: This work is funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) grant number 201630KRS-367087. CIHR had no role in the development of this protocol.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: Magali Bigras and Alain Boulet (Centre de santé et de services sociaux de Gatineau, Canada); Lynn R McLauchlin (St. Mary’s Hospital Center, Montreal, Canada); Silvia Duong (Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Canada); and Fanny Hersson (Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Canada).

Contributor Information

The Participatory Review Team:

Magali Bigras, Alain Boulet, Lynn R Mclauchlin, Silvia Duong, and Fanny Hersson

References

- 1.Grant RW, Ashburner JM, Hong CS, et al. Defining patient complexity from the primary care physician’s perspective: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:797–804. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katerndahl DA, Wood R, Jaén CR. A method for estimating relative complexity of ambulatory care. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:341–7. 10.1370/afm.1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica 2012;2012:1–22. 10.6064/2012/432892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaink A, Kuluski K, Lyons R, et al. A scoping review and thematic classification of patient complexity: offering a unifying framework. J Comorb 2012;2:1–9. 10.15256/joc.2012.2.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ 2012;345:e5205 10.1136/bmj.e5205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Binswanger IA, et al. Primary care physician perceptions on caring for complex patients with medical and mental illness. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:945–52. 10.1007/s11606-012-2005-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safford MM, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI. Patient complexity: more than comorbidity. the vector model of complexity. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(Suppl 3):382–90. 10.1007/s11606-007-0307-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson DR, Ziersch AM, Burgess T. I don’t think general practice should be the front line: Experiences of general practitioners working with refugees in South Australia. Aust New Zealand Health Policy 2008;5:20 10.1186/1743-8462-5-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martello C, Bessière G, Bigras M, et al. What do we mean when we say “This Patient is Complex”? NAPCRG Annual Conference New York: North American Primary Care Research Group, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pluye P, Bessière G, Bigras M, et al. Characteristics of complex care needs and interventions suited for patients with such needs: a participatory scoping review. NAPCRG Annual Conference New York: North American Primary Care Research Group, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laerum E, Steine S, Finset A. The Patient Perspective Survey (PPS): a new tool to improve consultation outcome and patient involvement in general practice patients with complex health problems. Patient Educ Couns 2004;52:201–7. 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00090-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peek CJ. Integrating care for persons, not only diseases. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2009;16:13–20. 10.1007/s10880-009-9154-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stiefel FC, Huyse FJ, Söllner W, et al. Operationalizing integrated care on a clinical level: the INTERMED project. Med Clin North Am 2006;90:713–58. 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fried TR, Tinetti M, Agostini J, et al. Health outcome prioritization to elicit preferences of older persons with multiple health conditions. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:278–82. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangin D, Stephen G, Bismah V, et al. Making patient values visible in healthcare: a systematic review of tools to assess patient treatment priorities and preferences in the context of multimorbidity. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010903 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St-Jacques S, Grenier S, Charland M, et al. Decisional needs assessment regarding Down syndrome prenatal testing: a systematic review of the perceptions of women, their partners and health professionals. Prenat Diagn 2008;28:1183–203. 10.1002/pd.2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weston WW. Informed and shared decision-making: the crux of patient-centered care. CMAJ 2001;165:438–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2006;60:301–12. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Légaré F, Ratté S, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;5:CD006732 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;9:CD006732 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff 2013;32:276–84. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melbourne E, Roberts S, Durand MA, et al. Dyadic OPTION: measuring perceptions of shared decision-making in practice. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:55–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Australian Commission On Safety And Quality In Health Care. Shared decision making: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2017. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/shared-decision-making/ (accessed 2 Feb 2017).

- 24.NICE. Shared Decision Making: National health service (NHS). 2016. http://sdm.rightcare.nhs.uk/ (accessed 2 Feb 2017).

- 25.NICE. The SHARE Approach: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2016. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/index.html (accessed 2 Feb 2017).

- 26.Bujold M. Patient’s representation of illness as an interdisciplinary communication channel. Anthropologie et Sociétés 2008;32:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bujold M. Le patient intégrateur: analyse de l’articulation d’une pluralité de voix / voies dans une clinique intégrative québécoise. Université Laval 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bujold M. Ethnomedical ethics with regard to patient plurivocality: between autonomy and heteronomy. Journal International de Bioéthique 2015;26:19–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaboury I, Bujold M, Boon H, et al. Interprofessional collaboration within Canadian integrative healthcare clinics: key components. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:707–15. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Légaré F, Stacey D, Pouliot S, et al. Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: a stepwise approach towards a new model. J Interprof Care 2011;25:18–25. 10.3109/13561820.2010.490502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Légaré F, Stacey D, Graham ID, et al. Advancing theories, models and measurement for an interprofessional approach to shared decision making in primary care: a study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:2 10.1186/1472-6963-8-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canada Research Chair in Shared Decision Making and Knowledge Translation. Interprofessional Approaches to Shared Decision Making (IP-SDM). 2017. http://www.decision.chaire.fmed.ulaval.ca/en/research/projects/interprofessional-approaches/

- 33.Légaré F, Brière N, Stacey D, et al. Implementing shared decision-making in interprofessional home care teams (the IPSDM-SW study): protocol for a stepped wedge cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e014023 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Légaré F, Stacey D, Brière N, et al. Healthcare providers' intentions to engage in an interprofessional approach to shared decision-making in home care programs: a mixed methods study. J Interprof Care 2013;27:214–22. 10.3109/13561820.2013.763777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muntinga ME, Hoogendijk EO, van Leeuwen KM, et al. Implementing the chronic care model for frail older adults in the Netherlands: study protocol of ACT (frail older adults: care in transition). BMC Geriatr 2012;12:19 10.1186/1471-2318-12-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Légaré F, O’Connor AC, Graham I, et al. Supporting patients facing difficult health care decisions: use of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. Can Fam Physician 2006;52:476–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.OHRI. Ottawa Decision Support Framework. 2015. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/odsf.html (accessed 27 June 2017).

- 38.Jacobsen MJ, O’Connor AM, Stacey D. Decisional needs assessment in populations. A workbook for assessing patients’ and practitioners’ decision making needs. Ottawa, Ontario: University of Ottawa, 2013. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/implement/Population_Needs.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I, et al. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ 2009;181:165–8. 10.1503/cmaj.081229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:29–45. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009;26:91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, et al. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:529–46. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. Synthesizing qualitative and quantitative health evidence: a guide to methods. Berkshire: Open University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheldon TA. Making evidence synthesis more useful for management and policy-making. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):1–5. 10.1258/1355819054308521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pluye P, Hong QN, Vedel I. The plurality of review methods and synthesis methods: opening-up the definition of systematic reviews [invited peer-reviewed paper on knowledge syntheses]. J Clin Epi. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, et al. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev 2017;6:61 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.North American Primary Care Research Group, 2013. What are the key processes associated to outcomes of participatory research with health organizations? A participatory systematic mixed studies review. NAPCRG annual meeting Ottawa: North American Primary Care Research Group [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pluye P, Nadeau N, Lehoux P. Comment favoriser la recherche clinique en pédopsychiatrie? Une expérience de recherche-action collaborative. Sante Ment Que 2001;26:245–66. 10.7202/014534ar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu Rev Public Health 2008;29:325–50. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waterman H, Tillen D, Dickson R, et al. Action Research: a systematic review and guidance for assessment. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:157 10.3310/hta5230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Argyris C, Putnam R, Smith D. Action science: concepts, methods, and skills for research and intervention. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munn-Giddings C, McVicar A, Smith L. [Systematic review of the uptake and design of action research in published nursing research, 2000-2005]. Rech Soins Infirm 2010;13:465–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Munten G, van den Bogaard J, Cox K, et al. Implementation of evidence-based practice in nursing using action research: a review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2010;7:135–57. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2009.00168.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soh KL, Davidson PM, Leslie G, et al. Action research studies in the intensive care setting: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:258–68. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis MM, Keller S, DeVoe J, et al. Characteristics and lessons learned from practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in the United States. J Healthc Leadersh 2012;2012:107–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garson DG. Garson DG, Reliability analysis. Statnotes: topics in multivariate analysis. Raleigh: North Carolina State University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0. Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:47–53. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Souto RQ, Khanassov V, Hong QN, et al. Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:500–1. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crowe M, Sheppard L. A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: alternative tool structure is proposed. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:79–89. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, et al. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Montreal, Canada: Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: final report. ESRC Methods Programme: Swindon, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Creswell J, Clark P V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bazeley P, Jackson K. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo Colorado: University of Colorado, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bujold M. Nvivo: a support tool for qualitative analysis. Workshop guide. Montreal, Canada: CAQI, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006;5:80–92. 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sullivan P. Qualitative data analysis using a dialogical approach. London: Sage, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pavel S, Nolet D. Handbook of terminology. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rihoux B, Qca MA. 25 years after “The Comparative Method”: mapping, challenges, and innovations. Polit Res Q 2013;66:167–235. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rihoux B, Ragin C. Configurational comparative methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. Data collection checklist Ottawa. Canada: Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group, 2002. http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf (accessed 10 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neuendorf KA. The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rich E, Lipson D, Libersky J, et al. Coordinating care for adults with complex care needs in the patient-centered medical home: Challenges and solutions [White Paper]. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012. http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Coordinating%20Care%20for%20Adults%20with%20Complex%20Care%20Needs.pdf (accessed 10 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rich EC, Lipson D, Libersky J, et al. Organizing care for complex patients in the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:60–2. 10.1370/afm.1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, et al. New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in 11 countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Aff 2011;30:2437–48. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Couture M, et al. Partners for the optimal organisation of the healthcare continuum for high users of health and social services: protocol of a developmental evaluation case study design. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006991 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2000;7:277–86. 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beaulieu MD, Proulx M, Jobin G, et al. When is knowledge ripe for primary care? An exploratory study on the meaning of evidence. Eval Health Prof 2008;31:22–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Bruin SR, Versnel N, Lemmens LC, et al. Comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions: a systematic literature review. Health Policy 2012;107:108–45. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kamerow D. How can we treat multiple chronic conditions? BMJ 2012;344:e1487 10.1136/bmj.e1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ouwens M, Wollersheim H, Hermens R, et al. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:141–6. 10.1093/intqhc/mzi016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Upshur R, Tracy C. Chronicity and complexity: Facing the challenges of chronic disease in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2008;54:1655–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD001431 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec. Plan stratégique 2015-2020: Québec: Gouvernement du Québec. 2015. http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2016/16-717-01W.pdf (accessed 06 Jun 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.