Abstract

Introduction

Nosocomial infections are serious complications that increase morbidity, mortality and costs and could potentially be avoidable. Antiseptic body wash is an approach to reduce dermal micro-organisms as potential pathogens on the skin. Large-scale trials with chlorhexidine as the antiseptic agent suggest a reduction of nosocomial infection rates. Octenidine is a promising alternative agent which could be more effective against Gram-negative organisms. We hypothesise that daily antiseptic body wash with octenidine reduces the risk of intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired primary bacteraemia and ICU-acquired multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) in a standard care setting.

Methods and analysis

EFFECT is a controlled, cluster-randomised, double-blind study. The experimental intervention consists in using octenidine-impregnated wash mitts for the daily routine washing procedure of the patients. This will be compared with using placebo wash mitts. Replacing existing washing methods is the only interference into clinical routine.

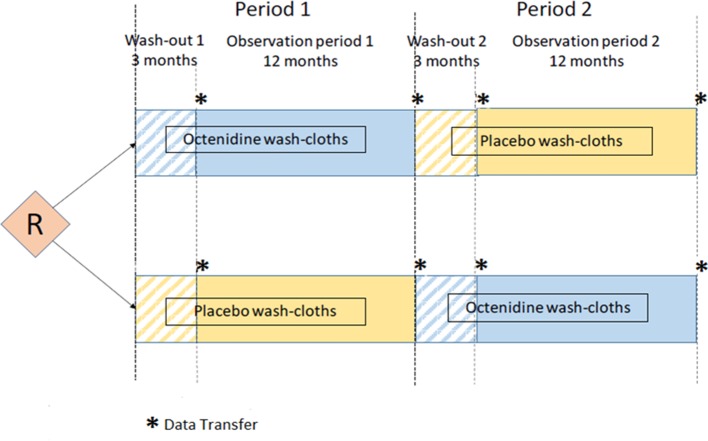

Participating ICUs are randomised in an AB/BA cross-over design. There are two 15-month periods, each consisting of a 3-month wash-out period followed by a 12-month intervention and observation period. Randomisation determines only the sequence in which octenidine-impregnated or placebo wash mitts are used. ICUs are left unaware of what mitts packages they are using.

The two coprimary endpoints are ICU-acquired primary bacteraemia and ICU-acquired MDRO. Endpoints are defined based on individual ward-movement history and microbiological test results taken from the hospital information systems without need for extra documentation. Data on clinical symptoms of infection are not collected. EFFECT aims at recruiting about 45 ICUs with about 225 000 patient-days per year.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig (number 340/16-ek) in November 2016. Findings will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

DRKS-ID: DRKS00011282.

Keywords: infection control, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

EFFECT is the first multicentre, cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled cross-over trial evaluating antiseptic body wash with octenidine.

Innovative data acquisition relies only on digitally available data from the hospital information systems (ward-movement history linked to microbiological test results).

EFFECT endpoints are algorithmically defined and are thus independent of possibly subjective, clinical considerations.

Possibly confounding variations in screening strategies can be described and included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis uses data on exact length of stay on intensive care unit (ICU) and takes competing events into account. Analysis focuses on ICU episodes longer than 48 hours, in which the patients are actually at risk for an ICU-acquired bacteraemia or multidrug-resistant organisms.

We have to deviate from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definitions since information on catheter days, antibiosis and clinical symptoms of infection are currently not generally available in digital form.

Introduction

Nosocomial bloodstream infections (BSIs) can cause serious complications for patients during their hospital stay.1 Patients on intensive care unit (ICU) are particularly vulnerable.2 BSIs are associated with increased morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs.3–9

Patients with infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) have higher mortality rates than patients with infections caused by antibiosis-sensitive organisms.10–13 A possible strategy to prevent nosocomial infections is the reduction of micro-organism reservoirs as sources of potential pathogens on the skin, in the nose, oropharynx and intestines.14 Antiseptic body wash is one approach to reduce dermal micro-organisms.15

The role of antiseptic body wash in preventing nosocomial infections is discussed controversially and at the start of the study there is no respective German national recommendation on its use as a daily routine.16 Several studies showed that antiseptic body wash with chlorhexidine reduces infection rates.15 17–23 Other studies did not confirm this.24 25

The colonisation of the patient’s skin with Gram-negative bacteria is reported as a hitherto underestimated source of nosocomial infections.26

The benefit of chlorhexidine towards colonisation and infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative (MDRGN) bacteria has not been investigated in many studies.27 We identified two recent cohort studies reporting a preventive effect of antiseptic body wash with chlorhexidine specifically on MDRGN bacteria,28 29 whereas two recent randomised trials do not report such an effect.25 30 The effect of chlorhexidine body wash may predominantly avoid BSIs caused by Gram-positive, coagulase-negative staphylococci.24 In addition, there is first evidence of the development of resistance mechanisms towards chlorhexidine,31–34 and side effects such as contact dermatitis or anaphylactic reactions.35

The primary aim of EFFECT is to investigate whether or not washing with antiseptics reduces nosocomial infections within the German healthcare setting. Thus, a placebo arm is a required comparator. We deemed a three-armed study design unfeasible. Thus, we had to choose between octenidine and chlorhexidine and preferred octenidine due to the following reasons:

Octenidine is a cationic antiseptic belonging to the class of bispyridines. It is bactericidal against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as fungicide.36 37 Octenidine may have a larger antibacterial activity spectrum than chlorhexidine, in particular towards Gram-negative bacteria.34 38 39

A development of resistance to octenidine has not been reported. No side effects of octenidine have been described.35

Only a few clinical studies have previously investigated antiseptic body wash with octenidine for the prevention of nosocomial infections.40–44 These publications are based on a very moderate number of centres and patients only. Octenidine was often combined with further interventions.40 43 44

Thus, a large study is needed to define the role of body wash with octenidine compared with placebo.

Methods and analysis

Study design

EFFECT is a controlled, cluster-randomised, double-blind study. The study intervention consists in using octenidine-impregnated wash mitts for the daily routine washing procedure of the patients, compared with using placebo wash mitts. The intervention will replace the existing washing methods and will be conducted by the nursing staff of the ICU once a day per patient.

The observation unit is the ICU, not the individual patient. Since the transmission of pathogens from one patient to another is an important risk in acquiring a nosocomial infection/colonisation with MDRO, a ward-wide intervention is required.

We use an AB/BA cross-over design, as ICUs are not directly comparable with each other regarding the risk of infection. The incidence of infection (especially caused by MDRO) on an ICU strongly depends on the composition of the patient population and its disease patterns, its distribution of lengths of stay on ICU, the local pathogen spectrum and the proportion of patients already infected or colonised by relevant pathogens on admission to the ICU and whether this is known. The screening strategy in the participating ward is important too and differs widely. Thus, a parallel-group design would not be suitable.

Each ICU participates in two observation periods: in one period patients are washed with octenidine-impregnated wash mitts and in the other one with placebo wash mitts. The ICUs are randomised concerning the order of placebo/octenidine or octenidine/placebo (block randomisation) to compensate for period effects (secular trends). The study biometrician has generated an allocation sequence list using block randomisation. Randomisation is performed centrally by the study team based on this list. The study team then coordinates that wash mitts are delivered by the manufacturer to the ICUs based on the assigned colour sequence.

Each of the two observation periods per ICU lasts 1 year, such that seasonal fluctuations can be eliminated. Each 1-year observation period is preceded by a 3-month wash-out phase. This helps to minimise relevant overlap of episodes of ICU patients between the observation phases. It furthermore safeguards against a possible carry over effect, in case an ICU already performs body wash with antiseptics.

Figure 1 illustrates the EFFECT study design.

Figure 1.

EFFECT study design. R indicates time of randomisation of participating intensive care units.

The first participating ICUs have been enrolled in January 2017. Further ICUs will be opened over a period of approximately 6 months. Thus, a total study length of 36 months is expected.

Blinding and monitoring

The type of wash mitts (octenidine or placebo) is blinded. This minimises potential sources of bias, since the decision to request a microbiological test is partly subjective, but the test frequency influences the EFFECT endpoints. The nursing staff could also consciously or unconsciously be influenced in their washing routine.

Two different colours (blue and green) are used for the packaging of the wash sets. The manufacturer (Schülke & Mayr, Norderstedt, Germany) assigned the colours to the octenidine and placebo wash mitts before the start of production. This allocation is documented in a sealed envelope, inaccessible to third parties, participants and study team throughout the study. Hence, the colour assignment is only known to the manufacturer.

Octenidine is a registered cosmetic product with a very good tolerability profile. In an unlikely case of individual intolerability towards one of the test products (octenidine or placebo), the care personal will wash the patient with the ICU’s conventional washing method throughout his remaining stay on ICU. The care personal will report the incidence directly to the manufacturer, following the standard regulations in the use of registered cosmetic products. The manufacturer informs the study biometrician at regular intervals about reported adverse events. No unblinding will take place in such a case, since it would have no consequence concerning the further treatment of the patient.

The placebo wash mitts contain a minimum amount of preservatives, required for conservation, but do not have a relevant disinfecting effect. The placebo wash mitts are produced by the same manufacturer that produces the wash mitts containing octenidine.

The compliance with the assigned intervention will be monitored by supervising the consumption of the test product taking into account the number of beds and the current ward occupancy rate and by questioning the ward staff during monitoring visits as well as frequent telephone contacts in between the monitoring visits.

EFFECT does not have a data monitoring committee; we do not deal with individual patient data and rely on routine digital data from the participating ICUs. However, EFFECT has a scientific independent advisory board (IAB), consisting of experts in microbiology, hygiene and intensive care, who are not involved in the study. The IAB will receive status reports regularly from the study team and would be consulted in case of unforeseen problems.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for ICUs

Patients receive a full body wash by the nursing staff once daily.

Standard operating procedures for MDRO screening are in force.

- Key data are digitally available from the hospital information system:

- individual patient ward-movement history as well as

- results of all individual microbiological tests during the complete hospital stay.

We include ICUs irrespective of their infection rates in the past.

Exclusion criteria for ICUs

ICU focuses on burn patients, as a body wash would be contraindicated.

ICU focuses on patients with bone marrow transplants, as these patients are often mobile and able to wash themselves.

ICU is paediatric, as wash mitts are only for use in children older than 3 years.

ICU participates in other (research) projects which might directly influence the endpoints of the EFFECT study.

Endpoint-relevant restructuring measures are expected in the ICU/hospital in the next 3 years from the start of the study (eg, change in specialisation and therefore the patient population with its types of diseases; change of the microbiological laboratory).

We plan to recruit about 45 ICUs throughout Germany.

Data acquisition

EFFECT will obtain all essential data from the hospital information systems. The data required for the study are retrieved by the hospitals routinely and will be transmitted digitally in an anonymous form to the Clinical Trial Centre Leipzig.

EFFECT requires two types of data over the entire hospital stay for all cases that have at least one episode on a participating ICU:

Individual ward-movement history (timestamps of admission, transfers to other wards, discharge/death).

Microbiological test results—both negative and positive (with antibiogram, if available)—with information on the type of specimen and time/date of sample collection/receipt in the laboratory.

These two data sets can be linked using a case identifier as illustrated in figure 2 in a fictive example.

Figure 2.

Example of a ward-movement history linked to microbiological test results between hospital admission (HA) and hospital discharge (HD), showing a case with two episodes on two different EFFECT-participating intensive care units (ICUs). N refers to any non-participating ward. This case shows an ICU-acquired secondary bacteraemia as well as ICU-acquired multidrug-resistant organisms (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) on ICU2.

Case identifiers will be anonymised before data transfer but such that the link between both data types is preserved.

The data will be transferred after each washout and each observation period, respectively.

Endpoint definitions

The EFFECT study has two coprimary endpoints ICU-acquired primary bacteraemia and ICU-acquired MDRO.

Endpoints were chosen to address major areas of nosocomial colonisations and infections that may be influenced by infection prevention measures. In addition, endpoints need to be defined operationally from the data acquired from the hospital information systems.

Primary bacteraemia acquisitions and MDRO acquisitions can only plausibly be attributed to the ICU if

they were not present at ICU admission

the micro-organisms were recovered from samples collected after a minimum length of stay on ICU (48 hours).

We therefore only analyse ICU episodes which last longer than 48 hours and in which no relevant pathogen was detected in samples collected beforehand (from hospital admission until 48 hours on ICU). Primary bacteraemia acquisitions and MDRO acquisitions are attributed to the ICU episode if detected in samples collected up to 48 hours after discharge from ICU.

ICU-acquired primary bacteraemia

We define bacteraemia as

pathogen organism identified in a blood culture or

common skin commensal organism identified in a blood culture, unless there is a second blood culture taken within the following 48 hours that does not confirm the same organism.

We use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classification of pathogen organisms and common skin organisms.45

Note we deviate from common practice as we reverse the burden of proof: EFFECT counts all bacteraemia with skin commensal organisms, unless a following negative blood culture suggests a possible contamination. If an ICU omits the recommended second blood culture for confirmation and instates therapy directly, patients are at risk of unnecessary treatment. In addition, not following the guidelines seemingly reduces the reported bacteraemia incidence. However, we cannot exclude that a second sample taken within 48 hours but after initiation of antibiosis became negative due to treatment.

Figure 3 illustrates the algorithm we use to classify bacteraemia into primary and secondary.

Figure 3.

The algorithm used to classify bacteraemia. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A possible explanation for observing a bacteraemia is that an organism enters the bloodstream from an infection site elsewhere. In this case, a mistake in infection control is an unlikely cause.

We therefore define a bacteraemia as secondary if

the organism found in the blood culture is also detected in other relevant clinical material during the entire hospital stay or

the organism found in the blood culture is listed by CDC45 as exceptional. (The list of exceptional organisms consists of organisms that are likely to cause a mucosa barrier injury in case of an infection and those which are likely community acquired.)

We exclude stool samples and skin, nose, throat and rectal swabs as relevant clinical materials since organisms detected there indicate more likely a colonisation than an infection.

We also exclude catheter tips from clinical materials since detecting the same organism on catheter tips as in the blood rather confirms a primary bacteraemia.

A bacteraemia is considered primary if it is not secondary. We expect that the impact of infection control measures is more pronounced in the endpoint ‘primary bacteraemia’ than in ‘any bacteraemia’.

We use the term bacteraemia. However, a bacteraemia is largely equivalent to the laboratory-confirmed BSI according to the CDC definitions,45 if one assumes that blood cultures are drawn mainly in case of a suspected infection.

Secondary endpoints related to bacteraemia are

ICU-acquired primary bacteraemia with pathogen organism

ICU-acquired primary bacteraemia with pathogen, Gram-positive organism

ICU-acquired primary bacteraemia with pathogen, Gram-negative organism

ICU-acquired primary bacteraemia with skin commensal organism

ICU-acquired primary or secondary bacteraemia.

ICU-acquired MDRO

The second coprimary endpoint is ICU-acquired MDRO: MDRO comprise methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and MDRGN bacteria in all clinical materials including skin, nose, throat and rectal swabs as well as stool samples.

For each episode, the first endpoint-specific pathogen detection counts.

Secondary endpoints related to MDRO are

ICU-acquired MRSA

ICU-acquired VRE

ICU-acquired MDRGN bacteria.

Statistical analysis

Analysis set

Data for each observation period will be transferred digitally. For all informative ICU episodes (longer than 48 hours) the endpoints will be determined algorithmically from the respective microbiological data.

The primary analysis is intent to treat. A per protocol analysis will be performed only in case the ICUs systematically deviate from the assigned washing procedures.

Analytical methods

Discharge, transfer to another unit and death on ICU are competing events for the detection of nosocomial infection or colonisation. A correct statistical analysis should therefore use standard methods for the evaluation of ‘competing risks’.46 47

Time to endpoint data from informative episodes will be analysed with Cox’s proportional hazard regression concerning their cause-specific hazard function. Secondarily, Fine-Gray regression on subdistribution hazards will be performed. Results will be illustrated plotting both estimated hazard functions and cumulative incidence curves.

The basic model contains the period (first or second observation year) and the intervention (octenidine or placebo) as fixed effects as well as an ICU-specific random effect with a random interaction term of the ICU with the intervention’s effect. This model structure is used for both coprimary endpoints to estimate the intervention’s effect as hasard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Secondary endpoints are handled in the same way.

Test strategy

For both coprimary endpoints, we use the two-sided Wald test concerning the intervention effect to perform a two-sided test of the null hypotheses that the cause-specific HR of the intervention is 1. The significance level is set to α=5%.

As two primary endpoints are investigated, we correct for multiplicity using the Hochberg step-up procedure.48 The overall null hypothesis ‘antiseptic body wash with octenidine has no effect’ is rejected if one of the two coprimary endpoints is significant at the level α/2 or both at level α.

As EFFECT is a cross-over study, no interim analysis is planned.

Sample size considerations

We derived an approximate sample size formula: the intervention effect (octenidine vs placebo) can be quantified as log HR lhrk (k=1:K) for each of the K participating ICUs. The specified analytical model essentially corresponds to a random effect meta-analysis of these ICU-specific results.

The log HRs lhrk are approximately normally distributed with variance

| (1) |

where Ek denotes the number of observed events in ICU k (k=1:K).

Let θ denote the overall intervention effect to be detected (as log HR). We assume that the intervention effect is not identically θ for all ICUs, but that each ICU has an individual intervention effect θk which is normally distributed with mean θ and heterogeneity variance τ2.

Substituting (1) in the well-known variance formula from the standard model for random effect meta-analysis (compare 49 (p1674): formula (3)) we get:

| (2) |

where E=sumk(Ek) and θ^ denotes the estimate for θ.

We need an upper limit for . This term would be 1/K, if all Ek were equal. We assume (Ek2)/E2≤C/K for constant C≈3–4 based in numerical simulations with scenarios assuming heterogeneity of ICU in site and event risk level.

Requiring power=1−β for a two-sided test at significance level α translates into the requirement:

| (3) |

where Zp denotes the p-percentile of the standard normal distribution.

Equating (2)=(3) and solving for E leads to:

| (4) |

Equation (4) shows that two aspects have to be considered simultaneously: we need to observe enough patient-days to observe the required number of events. On the other hand, we must include enough ICUs such that τ2 can be estimated and the negative heterogeneity term −τ2*C/K in the denominator does not inflate the number of required events.

Sample size requirements and assumptions

In EFFECT, we want to detect a risk reduction of 25% to a HR of 0.75; this corresponds to a log HR θ=log(0.75)≈−0.29. This effect size is in the order of magnitude of effects reported in successful clinical trials with chlorhexidine.

We require 90% power and plan with a two-sided significance level of α=0.025, since we deal with two coprimary endpoints.

We assume a moderate heterogeneity in intervention effect of τ=0.15 among ICUs which is in the order of θ/2.

To achieve C/K≤0.1, we need K=30 for C=3 and K=40 for C=4. In both cases, we need to observe E=905 events.

We conservatively assume a rate of two events per 1000 patient-days for primary bacteraemia, expecting nosocomial MDRO to be more frequent. Due to varying definitions and analytical methods in the literature, evidence for this assumption is limited.

Thus, we plan to recruit 35–45 ICUs with a potential of 200 000 to 225 000 patient-days per year for both 1-year observation periods.

Ethics and dissemination

Case identifiers will be anonymised, before being transferred digitally to the Clinical Trial Centre Leipzig.

Data processing and evaluation, which takes place at the Clinical Trial Centre, complies with data protection regulations. Only the study team has access to full study data. These persons are bound to maintain confidentiality. The data are protected against third-party access.

The data acquisition and transfer was endorsed by the data protection officer of the University of Leipzig/Faculty of Medicine. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig (number 340/16-ek) in November 2016.

The authors commit to report data as recommended by CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines and findings will be published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated through scientific and professional conferences. The final trial report will link the full protocol and protocol amendments.

Protocol amendments

Relevant protocol changes will be submitted to the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig for approval.

Discussion

The aim of EFFECT is to investigate whether daily antiseptic body wash with octenidine-impregnated wash cloths compared with placebo wash mitts reduces the risk of ICU-acquired bacteraemia and ICU-acquired MDRO in a standard care setting.

EFFECT essentially relies on digitally available data from the hospital information systems. This unique design feature has several benefits:

The intervention into clinical routine is minimal. Except for using a different washing method, ICU staff is not involved with study-specific documentation.

Full data on exact length of stay on ICU are required for a state-of-the-art statistical analysis which must take timing of competing events into account.46 47 50 51 The time profile of the risk of nosocomial events can be described (hazard functions, cumulative incidence functions).

Length of stay data also enable us to focus analysis on those ICU episodes longer than 48 hours, in which the patients are actually at risk for an ICU-acquired bacteraemia or MDRO.

Current CDC definitions are complex and require particular documentation effort and a considerable amount of clinical judgement. In EFFECT, we approximate CDC definitions with data from the hospital information system. Our corresponding endpoints are defined algorithmically, linking individual ward-movement data with microbiological test results. This is fully automatic and independent of possibly subjective, clinical considerations.

Screening intensity both on ICU and in the entire hospital affect MDRO endpoints in particular. Even though in EFFECT each ICU is essentially compared with itself, it is difficult to ensure that the ward-specific screening intensity (eg, in case of an MRSA outbreak) remains constant over 2.5 years. With our approach, we have all positive or negative microbiological test results to describe this confounder and incorporate it in the analyses.

We hold that these benefits outweigh obvious limitations:

As we only analyse microbiological findings, we cannot fully distinguish between colonisation and infection. However, concerning bacteraemia, our classification in primary and secondary bacteraemia without the inclusion of other clinical data can be seen as an operative and objective approach to the CDC criteria for laboratory-confirmed BSI.

Since catheter days are not reliably electronically recorded yet in every hospital, we cannot decide whether a bacteraemia is catheter associated or not. However, several studies show that antiseptic body wash might be able to generally reduce the risk of acquiring a bacteraemia/BSI.17 18

We expect that in the future more patient data will be collected digitally in standardised manners (eg, catheter days, radiological findings, laboratory parameters, antibiosis). EFFECT’s innovative data management may lead the way for future infection prevention research and daily infection control based on algorithms using digital-available data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yasmine Breitenstein, Sinidu Deneke and Dr Bettina Lutze for their contributions in study development, protocol finalisation and implementation.

Footnotes

AM and DH contributed equally.

Contributors: IFC is the principal investigator of the study. AM and DH made substantial contributions to conception and design. DH is the responsible statistician. AM adapted the medical definition of the endpoints to the digital mode of data acquisition. AM wrote the first draft of the article; DH revised the first draft and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. IFC and OB revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) (CH 1525/1-1). The manufacturer is paid factory costs for producing and providing the wash mitts (octenidine and placebo).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee of the University of Leipzig (number 340/16-ek).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lambert ML, Suetens C, Savey A, et al. . Clinical outcomes of health-care-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance in patients admitted to European intensive-care units: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:30–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70258-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonten MJ. Healthcare epidemiology: ventilator-associated pneumonia: preventing the inevitable. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:115–21. 10.1093/cid/ciq075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renaud B, Brun-Buisson C. Outcomes of primary and catheter-related bacteremia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1584–90. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.9912080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prowle JR, Echeverri JE, Ligabo EV, et al. . Acquired bloodstream infection in the intensive care unit: incidence and attributable mortality. Crit Care 2011;15:R100 10.1186/cc10114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, Tafflet M, et al. . Excess risk of death from intensive care unit-acquired nosocomial bloodstream infections: a reappraisal. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:1118–26. 10.1086/500318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laupland KB, Zygun DA, Davies HD, et al. . Population-based assessment of intensive care unit-acquired bloodstream infections in adults: incidence, risk factors, and associated mortality rate. Crit Care Med 2002;30:2462–7. 10.1097/00003246-200211000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittet D. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. JAMA 1994;271:1598 10.1001/jama.1994.03510440058033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valles J, Leon C. Spanish Collaborative Group for Infections in Intensive Care Units of Sociedad Espanola de Medicina Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias (SEMIUC). Nosocomial bacteremia in critically ill patients: a multicenter study evaluating epidemiology and prognosis. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:387–95. 10.1093/clinids/24.3.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J. Bacteremia and severe sepsis in adults: a multicenter prospective survey in ICUs and wards of 24 hospitals. French Bacteremia-Sepsis Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154(3 Pt 1):617–24. 10.1164/ajrccm.154.3.8810595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiazGranados CA, Zimmer SM, Klein M, et al. . Comparison of mortality associated with vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible enterococcal bloodstream infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:327–33. 10.1086/430909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, et al. . Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:53–9. 10.1086/345476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Kraker ME, Wolkewitz M, Davey PG, et al. . Burden of antimicrobial resistance in European hospitals: excess mortality and length of hospital stay associated with bloodstream infections due to Escherichia coli resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:398–407. 10.1093/jac/dkq412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sostarich AM, Zolldann D, Haefner H, et al. . Impact of multiresistance of gram-negative bacteria in bloodstream infection on mortality rates and length of stay. Infection 2008;36:31–5. 10.1007/s15010-007-6316-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao D, Song J, Gao X, et al. . Selective oropharyngeal decontamination versus selective digestive decontamination in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:3617–24. 10.2147/DDDT.S84587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popovich KJ, Hota B, Hayes R, et al. . Effectiveness of routine patient cleansing with chlorhexidine gluconate for infection prevention in the medical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:959–63. 10.1086/605925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.KRINKO beim Robert-Koch-Institut. Praevention von Infektionen, die von Gefaesskathetern ausgehen: Teil 1 - Nichtgetunnelte zentralvenose Katheter Empfehlung der Kommission fur Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionspravention (KRINKO) beim Robert Koch-Institut. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2017;60:171–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Climo MW, Yokoe DS, Warren DK, et al. . Effect of daily chlorhexidine bathing on hospital-acquired infection. N Engl J Med 2013;368:533–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. . Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2255–65. 10.1056/NEJMoa1207290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bleasdale SC, Trick WE, Gonzalez IM, et al. . Effectiveness of chlorhexidine bathing to reduce catheter-associated bloodstream infections in medical intensive care unit patients. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2073–9. 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milstone AM, Elward A, Song X, et al. . Daily chlorhexidine bathing to reduce bacteraemia in critically ill children: a multicentre, cluster-randomised, crossover trial. Lancet 2013;381:1099–106. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61687-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munoz-Price LS, Hota B, Stemer A, et al. . Prevention of bloodstream infections by use of daily chlorhexidine baths for patients at a long-term acute care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:1031–5. 10.1086/644751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montecalvo MA, McKenna D, Yarrish R, et al. . Chlorhexidine bathing to reduce central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection: impact and sustainability. Am J Med 2012;125:505–11. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karki S, Cheng AC. Impact of non-rinse skin cleansing with chlorhexidine gluconate on prevention of healthcare-associated infections and colonization with multi-resistant organisms: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2012;82:71–84. 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noto MJ, Wheeler AP. Understanding chlorhexidine decolonization strategies. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1351–4. 10.1007/s00134-015-3846-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boonyasiri A, Thaisiam P, Permpikul C, et al. . Effectiveness of chlorhexidine wipes for the prevention of multidrug-resistant bacterial colonization and hospital-acquired infections in intensive care unit patients: a randomized trial in Thailand. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016;37:245–53. 10.1017/ice.2015.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cassir N, Papazian L, Fournier PE, et al. . Insights into bacterial colonization of intensive care patients’ skin: the effect of chlorhexidine daily bathing. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015;34:999–1004. 10.1007/s10096-015-2316-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derde LP, Dautzenberg MJ, Bonten MJ. Chlorhexidine body washing to control antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in intensive care units: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:931–9. 10.1007/s00134-012-2542-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung YK, Kim JS, Lee SS, et al. . Effect of daily chlorhexidine bathing on acquisition of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) in the medical intensive care unit with CRAB endemicity. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:1171–7. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin MY, Lolans K, Blom DW, et al. . The effectiveness of routine daily chlorhexidine gluconate bathing in reducing Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae skin burden among long-term acute care hospital patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35:440–2. 10.1086/675613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derde LP, Cooper BS, Goossens H, et al. . Interventions to reduce colonisation and transmission of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in intensive care units: an interrupted time series study and cluster randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:31–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horner C, Mawer D, Wilcox M. Reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine in staphylococci: is it increasing and does it matter? J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:2547–59. 10.1093/jac/dks284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suwantarat N, Carroll KC, Tekle T, et al. . High prevalence of reduced chlorhexidine susceptibility in organisms causing central line-associated bloodstream infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35:1183–6. 10.1086/677628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baillie L. Chlorhexidine resistance among bacteria isolated from urine of catheterized patients. J Hosp Infect 1987;10:83–6. 10.1016/0195-6701(87)90037-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srinivasan VB, Singh BB, Priyadarshi N, et al. . Role of novel multidrug efflux pump involved in drug resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS One 2014;9:e96288 10.1371/journal.pone.0096288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lachapelle JM. A comparison of the irritant and allergenic properties of antiseptics. Eur J Dermatol 2014;24:3–9. 10.1684/ejd.2013.2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubner N-O, Siebert J, Kramer A, et al. . a modern antiseptic for skin, mucous membranes and wounds. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2010;23:244–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sedlock DM, Bailey DM. Microbicidal activity of octenidine hydrochloride, a new alkanediylbis[pyridine] germicidal agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985;28:786–90. 10.1128/AAC.28.6.786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koburger T, Hübner NO, Braun M, et al. . Standardized comparison of antiseptic efficacy of triclosan, PVP-iodine, octenidine dihydrochloride, polyhexanide and chlorhexidine digluconate. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:1712–9. 10.1093/jac/dkq212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Müller G, Langer J, Siebert J, et al. . Residual antimicrobial effect of chlorhexidine digluconate and octenidine dihydrochloride on reconstructed human epidermis. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2014;27:1–8. 10.1159/000350172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohr U, Mueller C, Wilhelm M, et al. . Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus whole-body decolonization among hospitalized patients with variable site colonization by using mupirocin in combination with octenidine dihydrochloride. J Hosp Infect 2003;54:305–9. 10.1016/S0195-6701(03)00140-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spencer C, Orr D, Hallam S, et al. . Daily bathing with octenidine on an intensive care unit is associated with a lower carriage rate of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 2013;83:156–9. 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris PN, Le BD, Tambyah P, et al. . Antiseptic body washes for reducing the transmission of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus: a cluster crossover study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015;2:ofv051 10.1093/ofid/ofv051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohler P, Sommerstein R, Schönrath F, et al. . Effect of perioperative mupirocin and antiseptic body wash on infection rate and causative pathogens in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:e33–e38. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.04.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gastmeier P, Kämpf KP, Behnke M, et al. . An observational study of the universal use of octenidine to decrease nosocomial bloodstream infections and MDR organisms. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:2569–76. 10.1093/jac/dkw170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.CDC. Bloodstream infection event (central line-associated bloodstream infection and non-central line-associated bloodstream infection). 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrent.pdf (accessed 24 may 2017).

- 46.Schumacher M, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, et al. . Hospital-acquired infections-appropriate statistical treatment is urgently needed!. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1502–8. 10.1093/ije/dyt111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolkewitz M, Cooper BS, Bonten MJ, et al. . Interpreting and comparing risks in the presence of competing events. BMJ 2014;349:g5060 10.1136/bmj.g5060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hochberg Y. On the classical choice of variance stabilizing transformations and an application for a Poisson variate. 1988. http://biomet.oxfordjournals.org/content/75/4/803.full.pdf+html (accessed 1 Aug 2016).

- 49.Whitehead A, Whitehead J. A general parametric approach to the meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Stat Med 1991;10:1665–77. 10.1002/sim.4780101105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolkewitz M, Palomar-Martinez M, Olaechea-Astigarraga P, et al. . A full competing risk analysis of hospital-acquired infections can easily be performed by a case-cohort approach. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;74:187–93. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolkewitz M, Vonberg RP, Grundmann H, et al. . Risk factors for the development of nosocomial pneumonia and mortality on intensive care units: application of competing risks models. Crit Care 2008;12:R44 http://ccforum.com/content/12/2/R44 10.1186/cc6852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.