Abstract

Introduction

We developed and validated a new parsimonious scale to measure stoic beliefs. Key domains of stoicism are imperviousness to strong emotions, indifference to death, taciturnity and self-sufficiency. In the context of illness and disease, a personal ideology of stoicism may create an internal resistance to objective needs, which can lead to negative consequences. Stoicism has been linked to help-seeking delays, inadequate pain treatment, caregiver strain and suicide after economic stress.

Methods

During 2013–2014, 390 adults aged 18+ years completed a brief anonymous paper questionnaire containing the preliminary 24-item Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale (PW-SIS). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test an a priori multidomain theoretical model. Content validity and response distributions were examined. Sociodemographic predictors of strong endorsement of stoicism were explored with logistic regression.

Results

The final PW-SIS contains four conceptual domains and 12 items. CFA showed very good model fit: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.05 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.07), goodness-of-fit index=0.96 and Tucker-Lewis Index=0.93. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78 and ranged from 0.64 to 0.71 for the subscales. Content validity analysis showed a statistically significant trend, with respondents who reported trying to be a stoic ‘all of the time’ having the highest PW-SIS scores. Men were over two times as likely as women to fall into the top quartile of responses (OR=2.30, 95% CI 1.44 to 3.68, P<0.001). ORs showing stronger endorsement of stoicism by Hispanics, Blacks and biracial persons were not statistically significant.

Discussion

The PW-SIS is a valid and theoretically coherent scale which is brief and practical for integration into a wide range of health behaviour and outcomes research studies.

Keywords: stoicism, help-seeking, health behaviour theories, masculinity, patient perspectives, gender

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale (PW-SIS) is a new, theoretically coherent, multidimensional scale which measures stoic beliefs and sense of self along four domains: stoic taciturnity, stoic endurance, stoic serenity and stoic death indifference.

The PW-SIS contains 12 items and demonstrates good psychometric properties and content validity in a large sample (n=390) of educated adults.

Mean stoicism ideology scores were higher for men than women, but for both genders the most frequent scores were neutral on stoic ideology, and the response distributions by gender overlapped almost completely.

Further validation of the PW-SIS in demographically and socioeconomically diverse populations will improve its generalisability.

Introduction

Stoicism is a school of philosophy which originated in ancient Greece.1–3 Core elements in the classical definition of stoicism were an idealisation of imperviousness to strong emotions, and an indifference to death.3 Major Asian philosophical systems of thought, such as Buddhism and Confucianism, also endorsed stoic principles and teachings.4 5 Beginning in the 19th century, academic and popular philosophers in Europe and the Americas were exposed to and influenced by Asian philosophy and religion. Therefore, it may not always be possible to distinguish whether particular strands of contemporary thought associated with stoicism originated in ancient Greece, ancient India or elsewhere. For example, using very different language and symbolism, both the Greek Stoics and the Buddha exhorted the student to live fully and completely in the present, while minimising concern about the future.

Contemporary meanings and connotations of stoicism have expanded beyond their ancient origins, to include ideals of taciturnity and self-sufficiency.6–8 Today, the philosophical principles of stoicism can be seen to closely align with some personal ideologies, values and behaviours which are commonplace across many industrial nations, and are evident in many non-Western cultures as well.9–12 For example, in the USA, the armed forces have explicitly embraced stoic ideology as a tool for mitigating combat stress.13 14

Previous research on stoicism and health

Much of the previous health-related research which mentions stoicism has invoked the term as a descriptor of particular patient groups or behaviours, without an explicit theoretical context.8 Stoicism is mentioned most frequently in studies related to pain (particularly cancer pain) and coping strategies; indeed stoicism has been labelled a ‘coping strategy’ in more than one study.6–8 15 16 Stoicism has also been invoked as a defining characteristic of masculinity and as a key explanatory factor for certain health behaviours and outcomes among men. There are several psychometric instruments that measure endorsement or adherence to social norms of masculinity, but these scales include only a few items which explicitly assess stoicism.17–19

Direct measurement of stoicism in previous health-related measures has implicitly defined stoicism as a pattern of behaviours, not as an ideology. The pain attitudes questionnaire (PAQ), published in 2001, has a brief subset of questions focused on stoic responses to physical pain.20–22 The stoicism items in this scale were designed to capture pain coping strategies of chronically ill or injured patients. Of the 29 items in the PAQ, most measured past actions (ie, pattern of behaviour) and only 2 were explicitly focused on ideology: #2 ‘When I am in pain I should keep it to myself,’ and #24 ‘Pain is something that should be ignored.’ The 20-item Liverpool Stoicism Scale (LSS) was first developed in 19923 and has not been widely used.24–27 The LSS predominantly (16 of 20 items) assesses a single theoretical domain (stoic taciturnity) of the four validated theoretical domains included in the final Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale (PW-SIS) (table 1).

Table 1.

Liverpool Stoicism Scale items and correspondence to Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale conceptual domains

| Item number | Liverpool Stoicism Scale item* | Closest domain from the Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale |

| 1 | I tend to cry at sad films. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 2 | I sometimes cry in public. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 3 | I do not let my problems interfere with my everyday life. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 4 | I tend not to express my emotions. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 5 | I like someone to hold me when I am upset. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 6 | I do not get emotionally involved when I see suffering on television. | Stoic serenity |

| 7 | I would consider going to a counsellor if I had a problem. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 8 | I tend to keep my feelings to myself. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 9 | I would not mind sharing my problems with a male friend. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 10 | It makes me uncomfortable when people express their emotions in front of me. | None |

| 11 | I don’t really like people to know what I am feeling. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 12 | I rely heavily on my friends for emotional support. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 13 | I always take time out to discuss my problems with my family. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 14 | One should keep a ‘stiff upper lip’. | Stoic serenity |

| 15 | I believe that it is healthy to express one’s emotions. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 16 | Getting upset over the death of a loved one does not help. | Stoic death indifference |

| 17 | I would not mind sharing my problems with a female friend. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 18 | A problem shared is a problem halved. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 19 | I would not cry at the funeral of a close friend or relative. | Stoic taciturnity |

| 20 | Expressing one’s emotions is a sign of weakness. | Stoic taciturnity |

*The Liverpool Stoicism Scale is reprinted with permission from Gaitniece-Putāne.24 © Department of Psychology, University of Latvia, 2005. All rights reserved.

Furthermore, the majority of items in the LSS focus on behaviour or conduct, for example, ‘I tend not to express my emotions.’ However, there are three items that are ideological, for example, “One should keep a ‘stiff upper lip’.” Both the LSS and the PAQ contain statements that are aphorisms (ie, ‘Pain is something that should be ignored’) or proverbs (ie, ‘A problem shared is a problem halved’). We consider these formats problematic, because these statements do not refer explicitly to the respondent. Consequently, agreement cannot be interpreted as a reflection of self-identity. Furthermore, aphorisms and proverbs may invite endorsement to a great extent simply because of familiarity. In fact, Yong et al found that item #24, ‘Pain is something that should be ignored,’ on the PAQ had a low alpha and reduced the internal consistency of their scale.21

Theoretical context

In 1983, Kathy Charmaz published a very influential sociological study on the ‘loss of self’ suffered by people with chronic illnesses.28 Although stoicism per se was mentioned only briefly, the idea that the suffering caused by disease emerges as much (or more) from threats to a person’s identity and sense of self as from purely bodily experiences of pathophysiology is one of the theoretical underpinnings of our work.

In this report, we attempt to articulate an explicit theory of stoicism and its potential impact on health. We theorise that stoicism is a system for self-regulation rather than a behaviour or personality trait. As a guide to ideal self-conduct, it requires self-conscious implementation and regular enforcement; in other words, stoicism is an ideology (eg, a belief system which informs one’s attitudes and actions with the inherent potential for internal resistance and conflict). Personal ideologies create expectations for people about who they are, as well as how they should and should not behave. For example, we theorise that people who strongly endorse a personal ideology of stoicism may be more likely to avoid or delay seeking professional medical intervention for serious signs and symptoms of disease. This personal ideology of self will not mandate behaviour in a deterministic fashion; rather, stoicism will create expectations of ideal behaviour (which may not always be met). In order to test these theoretical propositions in future research, a validated measure of an individual’s endorsement of stoic ideologies is needed.

The purpose of our study was to develop a theoretically coherent multidimensional scale to assess endorsement of a personal ideology of stoicism, and to empirically validate this scale in a multiethnic sample of healthy community-dwelling adults. We present the results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the multidomain PW-SIS, and discuss the potential usefulness of this tool for predicting constraints in health-related help-seeking behaviours. The PW-SIS is a generalised scale which assesses stoic beliefs and sense of self but does not explicitly measure health behaviours or health outcomes. Therefore, the PW-SIS can be used in a wide range of empirical research studies.

In addition, in this report we conducted an exploratory assessment of the association between high endorsement of stoicism and participant age, gender, and race and ethnicity. We expect stoic ideologies to be embedded in a larger system of cultural beliefs that may be related to age, gender, race and ethnicity, and other social characteristics.

Methods

Conceptual development of the stoicism ideology scale

Drawing on multiple scholarly and popular sources,1–3 6 15 29–31 we developed the preliminary 24-item Stoicism Ideology Scale (PW-SIS) to capture endorsement of five dimensions of stoicism (see online supplementary table 1 in the Technical Supplement). Based on our literature review and expert knowledge of philosophy, we defined each domain as follows:

bmjopen-2016-015137supp001.pdf (534.4KB, pdf)

Stoic taciturnity is the belief that one should conceal one’s problems and emotions from others.

Stoic endurance is the belief that one should endure physical suffering without complaining.

Stoic composure is the belief that one should control one’s emotions and behaviour under stress.

Stoic serenity is the belief that one should refrain from experiencing strong emotions.

Stoic death indifference is the belief that one should not fear or avoid death.

Each item in our scale was carefully worded to capture the respondents’ ideology, not their past behaviour, using a 5-point Likert response scale with the following responses: ‘disagree’, ‘somewhat disagree’, ‘not sure’, ‘somewhat agree’ and ‘agree’. Nine of the original 24 items were ‘reverse’ items that specified antistoic beliefs, that is, ‘I believe I should experience strong emotions.’ The participant version of the scale (pen-and-paper questionnaire) listed response codes of 0 (disagree) through 4 (agree). These responses were recoded during analysis to range from −2 (disagree) to +2 (agree). Consequently, an average score of 0 corresponds to a neutral stance—neither endorsement nor rejection of stoicism. Positive scores indicate endorsement of a stoic ideology, while negative scores indicate rejection of a stoic ideology.

Data collection

Data were collected over a period of 10 months during 2013–2014. All participants were university employees or students. Written consent forms were waived by the IRB to ensure respondent anonymity but all participants provided verbal informed consent. Each participant completed a brief paper-and-pencil questionnaire consisting of the 24-item preliminary PW-SIS, sociodemographic questions and a final single item ‘I try to be a stoic’ with a 7-item response scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘all the time’. The study population consisted of a convenience sample of 390 adults aged 18 years and older who were recruited in person by the authors in public common areas of university facilities (eg, cafeterias) using walk-up tables. Monetary incentives were not provided to participants. A study response rate could not be calculated due to the data collection methods.

Data analyses

Data analysis proceeded in five steps. During step 1, we examined univariate response distributions for each of the 24-scale items. A simple correlation matrix was examined to identify redundant items. Finally, we assessed content validity based on agreement with the statement ‘I try to be a stoic.’ As a result of step 1 analyses, six items were dropped from further analyses—including the entire stoic composure domain. Further details of this scale reduction step are included in the Technical Supplement (online supplementary table 2).

During step 2, we conducted a CFA of the reduced 18-item PW-SIS. CFA is the appropriate analytic choice to test scales that have an a priori, theoretically explicit subdomain structure.32–36 We used proc calis in SAS V.9.4 for the CFA. Based on the results of the first CFA, we eliminated two items with poor factor loadings (see online supplementary file 1, Technical Supplement, for details).

During step 3, we repeated the CFA on the reduced 16-item PW-SIS. Finally, for the purpose of parsimony we further reduced the total number of scale items to 12 (3 items in each of 4 domains) and conducted a CFA on the final 12-item version of the PW-SIS (step 4; see online supplementary table 3). Additional details and rationale for analytic steps 1–4 are included in online supplementary tables 1–3: Technical Supplement.

Step 5 of our analysis consisted of preliminary content validation, examination of response distributions for the overall and domain scores, and exploratory logistic regression modelling of sociodemographic predictors of strong endorsement of stoicism. For the logistic regression analysis, we categorised the outcome using the top quartile of the overall distribution of responses to represent strong endorsement of stoicism.

Results

The size of our study population (n=390) provided more than 15 respondents for each question in the preliminary scale, which exceeds the widely accepted norm of at least 10 respondents per question.37 Although skewed towards younger adults (78% of respondents were <25 years old), the study population was in other respects diverse (table 2). A majority self-identified as female (57%) and white (55%). Hispanics (15%) and Blacks (14%) were the second and third largest racial/ethnic groups, followed by Asians (9%) and biracial or other ethnicity (6%). A substantial minority of respondents (19%) were born outside the USA or Puerto Rico.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population (n=390)

| N | % | |

| Age (year) | ||

| 18–24 | 303 | 77.7 |

| 25+ | 87 | 22.3 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 221 | 56.7 |

| Male | 169 | 43.3 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White | 215 | 55.1 |

| Black | 55 | 14.1 |

| Hispanic | 59 | 15.1 |

| Asian | 36 | 9.2 |

| Biracial/other | 25 | 6.4 |

| Nativity | ||

| USA (including Puerto Rico) | 315 | 80.8 |

| Other | 75 | 19.2 |

The final four-domain, 12-item PW-SIS is shown in table 3. CFA of the final scale showed very good model fit with individual item factor loadings ranging from 0.48 to 0.76, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) =0.05 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.07), goodness-of-fit index=0.96 and Tucker-Lewis Index=0.93.

Table 3.

Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale

| Item | Domain | Original item number* |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I expect myself to hide my aches and pains from others. | Stoic endurance | Q2 |

| 2. I don’t believe in talking about my personal problems. | Stoic taciturnity | Q3 |

| 3. I expect myself to manage my physical discomfort without complaining. | Stoic endurance | Q5 |

| 4. I believe I should experience strong emotions. [reverse code] | Stoic serenity | Q8 |

| 5. When the time for my death comes, I believe I should accept it without fear. | Stoic death indifference | Q12 |

| 6. I expect myself to hide my strong emotions from others. | Stoic taciturnity | Q13 |

| 7. I would prefer to be unemotional. | Stoic serenity | Q14 |

| 8. I expect myself to manage my own problems without help from anyone. | Stoic taciturnity | Q15 |

| 9. I believe my physical pain is best handled by just keeping quiet about it. | Stoic endurance | Q17 |

| 10. I would be very upset if I knew my death was coming soon. [reverse code] | Stoic death indifference | Q18 |

| 11. I expect myself to avoid feeling intense emotions. | Stoic serenity | Q20 |

| 12. I would not allow myself to be bothered by the fear of death. | Stoic death indifference | Q24 |

Authors were asked to rate Items on a 5-point scale: Disagree, Somewhat disagree, Not sure, Somewhat agree or Agree. See Methods section for scoring instructions.

*See online supplementary table 1: Technical Supplement.

Relationships among the PW-SIS and its four conceptual domains are shown in table 4. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.64 to 0.71 for the subscales and was 0.78 for the 12-item PW-SIS. Scores for stoic taciturnity were strongly correlated with scores for both stoic endurance and stoic serenity, but stoic endurance and stoic serenity were not highly correlated with each other. Stoic death indifference had the highest (most stoic) mean scores among the four domains, and it was least correlated with the other three domains.

Table 4.

Conceptual domains of the Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale (PW-SIS)

| Domain | Mean score (95% CI) | Cronbach’s alpha | Correlation with ST score |

Correlation with SE score |

Correlation with SS score |

Correlation with SDI score |

| Stoic taciturnity (ST): the belief that one should conceal one’s problems and emotions from others (modern) | −0.08 (−0.18 to +0.02) | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.59 P<0.0001 |

0.53 P<0.0001 |

0.09 P=0.0729 |

| Stoic endurance (SE): the belief that one should endure physical suffering without complaining (modern) | +0.04 (−0.06 to +0.13) | 0.65 | 0.59 P<0.0001 |

1.00 | 0.35 P<0.0001 |

0.18 P=0.0005 |

| Stoic serenity (SS): the belief that one should refrain from experiencing strong emotions (classical) | −0.66 (−0.75 to −0.56) | 0.64 | 0.53 P<0.0001 |

0.35 P<0.0001 |

1.00 | 0.15 P=0.0031 |

| Stoic death indifference (SDI): the belief that one should not fear or avoid death (classical) | +0.08 (−0.03 to +0.18) | 0.69 | 0.09 P=0.0729 |

0.18 P=0.0005 |

0.15 P=0.0031 |

1.00 |

| Stoicism ideology scale (PW-SIS) | −0.16 (−0.22 to −0.09) | 0.78 | 0.79 P<0.0001 |

0.74 P<0.0001 |

0.72 P<0.0001 |

0.53 P<0.0001 |

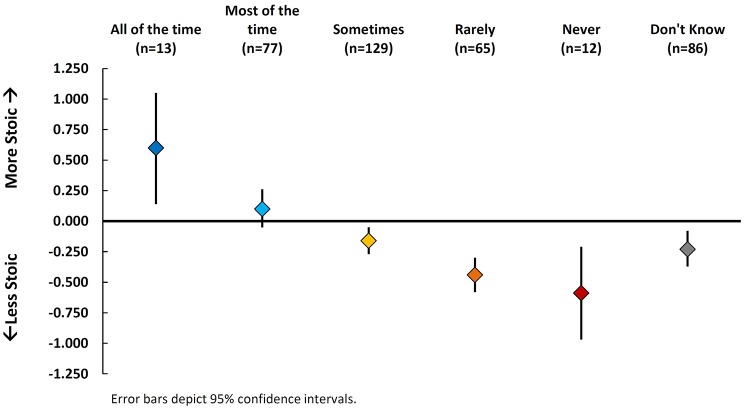

Figure 1 depicts mean PW-SIS scores by response to the statement ‘I try to be a stoic.’ There was a clear monotonic and statistically significant trend, with respondents who reported trying to be a stoic ‘all of the time’ having the highest stoicism scores, and respondents who reported trying to be a stoic ‘never’ having the lowest stoicism scores. Most respondents chose one of the three intermediate categories. Respondents who chose ‘I don’t know’ as their response had stoicism scores similar to those who said they ‘sometimes’ tried to be a stoic.

Figure 1.

Content validity of the Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale: mean scores by response to the statement ‘I try to be a stoic.’

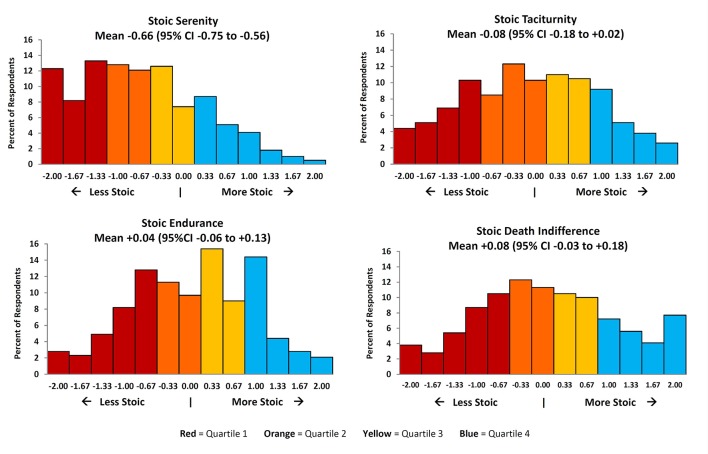

The distributions of mean scores for the four conceptual domain subscales are shown in figure 2. Domain scores comprised the mean score for the three questions in the domain. In this study population, respondents were least likely to endorse stoic serenity and most likely to endorse stoic death indifference.

Figure 2.

Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale: distribution of domain scores.

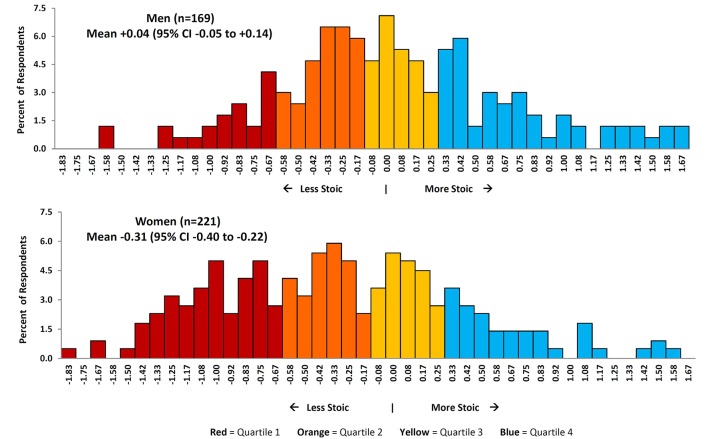

The full distribution of respondent scores is shown separately for women and men in figure 3. The distributions overlapped almost completely, but there were no men with the least stoic scores, and no women with the most stoic scores. Response distributions were skewed to the left for women (less stoic) and to the right for men (more stoic), consistent with a statistically significant difference in the mean scores for women (−0.31, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.22) and men (+0.04, 95% CI −0.05 to +0.14).

Figure 3.

Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale: distribution of overall scores by gender.

Results of an exploratory analysis of sociodemographic predictors of high endorsement of stoicism are shown in table 5. There is no a priori cut point designated as ‘highly stoic’ in the PW-SIS; in this analysis, the cut point used was a mean score greater than the 75th percentile of the overall response distribution. The top quartile of the distribution of all respondents (n=390) ranged from +0.33 to +1.67. Among women, 18.9% strongly endorsed stoicism, compared with 32.8% of men. After multivariate adjustment, men were over two times as likely as women to fall into the top quartile of responses (OR=2.30, 95% CI 1.44 to 3.68, P<0.001). Adults born in the USA or Puerto Rico were also twice as likely as adults born elsewhere to strongly endorse stoicism (OR=1.97, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.84, P=0.048). ORs showing stronger endorsement of stoicism by Hispanics, Blacks, biracial persons and adults 25 years and older were not statistically significant.

Table 5.

Sociodemographic predictors of a mean Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale score in the top quartile (>0.167)

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age 18–24 years | 1.00 (referent) | |

| Age 25–73 years | 1.34 (0.76 to 2.35) | ns |

| Men | 2.30 (1.44 to 3.68) | <0.001 |

| Women | 1.00 (referent) | |

| Asian | 0.93 (0.38 to 2.25) | ns |

| Black | 1.55 (0.78 to 3.09) | ns |

| Biracial/other | 1.70 (0.66 to 4.34) | ns |

| Hispanic | 1.88 (0.99 to 3.56) | ns |

| Whites | 1.00 (referent) | |

| Born in the USA | 1.97 (1.01 to 3.84) | 0.048 |

| Born elsewhere | 1.00 (referent) |

Discussion

The PW-SIS is a theoretically coherent, multidimensional scale which demonstrates good psychometric properties and content validity based on initial validation in a large sample of educated adults. The PW-SIS is also brief and practical for integration into a wide range of empirical research studies. In our study population of mostly younger adults, endorsement of stoicism varied by conceptual domain, with the weakest endorsement of the classical domain stoic serenity (aversion to strong emotions). Exploratory logistic regression analysis identified male gender and US birth as significant predictors of strong endorsement of stoicism. Finally, point estimates suggested higher endorsement of stoicism for Blacks, Hispanics and biracial persons compared with Whites, but these results were not statistically significant.

Integration of our theory of a stoic ideology of the self into existing health behaviour models could help explain the formation of beliefs and attitudes towards criterion-specific help-seeking behaviours. Reasoned action approaches—such as the integrative model of behaviour prediction—poorly define background factors that underlie belief formation.38 Measurement of self-concepts, such as stoicism ideologies, may help explain this population variability. Expanding health behaviour theory to include aspects of the self could also help inform health education messaging and risk-based communication.

Ironically, a personal ideology of stoicism almost guarantees failure to live up to one’s personal ideal. Experiences of illness and disease often involve transient weakness and functional limitations. With ageing, these experiences will increase in frequency, duration and severity for most people. Simply put, experiences of illness and disease tend to require aid—whether from health professionals in a formal context, or from family members or friends in an informal context. An ideology of stoicism creates an internal resistance to external objective needs, which can lead to negative consequences.8–12

Gender and stoicism

Stoicism is widely viewed as a defining attribute of masculinity. Instruments designed to assess endorsement of hegemonic masculine ideologies have included specific questions that touch on stoicism. However, the conceptual and measurement overlap between these instruments and the four-domain PW-SIS is minor.17 For example, in the widely used Personal Attributes Questionnaire, only 2 of 24 items relate to a single domain of the PW-SIS. The Conformance to Masculine Norms scale assesses 11 distinct domains of masculinity, of which only 2 (emotional control and self-reliance) partially overlap with domains of the PW-SIS.18 19 In our study, the results are notable because for both genders the most frequent scores were in the middle of the distribution (neutral on stoic ideology), and the response distributions for women and men overlapped almost completely. Despite the fact that men were twice as likely as women to strongly endorse stoic ideology, our results suggest that gendered stereotypes about stoicism (‘stoic men’ and ‘emotional women’) are overblown. Because the PW-SIS is agnostic to respondents’ genders, it is ideally suited to investigate the empirical reality of stoicism among both women and men. Furthermore, our finding that a minority of women strongly endorsed stoic ideology may be particularly important. For example, a study of major strain among family caretakers of elderly patients with dementia found that those who used stoicism as a coping strategy suffered burnout, while those who sought social support did not.39

Study limitations

In any questionnaire-based scale, validity of the individual items and the total scale against the concept of interest is of paramount concern. Unlike many psychometric instruments, the PW-SIS does not purport to measure a latent, inherent trait such as personality, or a clinically definable disorder such as depression or anxiety. Rather, we attempt to measure an explicit set of beliefs, which by definition are neither inborn nor immutable. Therefore, a robust assessment of the content validity of our scale items must come after publication and evaluation by multiple experts and researchers. We included a single questionnaire item ‘I try to be a stoic’ to assess content validity, but future validation and outcome studies could expand on this approach or include a qualitative component.

A related question pertains to the predictive validity of the PW-SIS. In other words, to what extent does strong endorsement of stoic ideology predict actual stoic behaviours? Predictive validity can only be rigorously addressed through prospective study designs.

Our study population, similar to many scale validation studies, was university based. Therefore, validity and generalisability to very different populations should not be assumed, but instead tested in future studies. In particular, validation of the PW-SIS among the elderly and persons of lower educational attainment would be valuable for health-related research.

Strengths of the PW-SIS

Our scale has several strengths. First, all items refer explicitly to the respondent; there are no aphorisms or proverbs. Second, each item refers to an expectation or belief about ideal self-conduct, rather than to a simple description of past behaviour. So, for example, Q5 states ‘I expect myself to manage my physical discomfort without complaining’ rather than ‘I always manage my physical discomfort without complaining.’ This distinction is critical to the theoretical underpinnings of the scale. Third, we deliberately chose not to mention disease or illness in the scale items, so that the scale would be appropriate for a wide range of study populations, including currently healthy individuals. (Although some items do explicitly mention ‘physical pain’ and ‘everyday aches and pains’.) Our intention was to capture the respondents’ global endorsement of stoicism as a code of ideal conduct. Finally, the PW-SIS does not reference gender norms, so it can serve as a tool to empirically investigate gender differences in stoic ideology.

Directions for future research

The PW-SIS should be validated in multiple study populations with a range of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Our theory that ideologies of stoicism will result in constraints on health-related behaviours needs to be empirically tested, ideally in rigorously designed prospective studies. Given the rise of patient-centred healthcare,40 41 understanding patients’ motivations and perspectives has never been more important. The current health education paradigm holds that improving patients’ knowledge of symptoms and signs will result in more timely help-seeking behaviour.38 42–44 Each year, thousands of individuals suffer needlessly and many die because of extended delays in seeking professional aid for acute medical conditions (eg, myocardial infarctions, strokes, diabetic emergencies, cancer complications and pain, and acute exacerbations of congestive heart failure).45–52 Numerous studies have been conducted to attempt to elucidate the reasons behind patient delays,46–51 53 with the ultimate goal of designing education programmes and interventions that will result in timely help-seeking. Significant risk factors for help-seeking reluctance have been identified (eg, Black race52 54 55) but much of the variation remains unexplained and we still lack a complete understanding of why certain patients and not others delay seeking aid.

A distinction of our theory is movement of the focus of inquiry away from the disease and the patient’s relationship to the disease (eg, health knowledge, symptom awareness, ability to comply with self-care regimens) and onto patients’ sense of self—their self-concepts and self-identity.56 We hypothesise that illness behaviours may become ‘noncompliant’ or ‘irrational’ or ‘self-harming’ when specific courses of action would create an internal conflict with patients’ ideas of who they are. Specifically, we posit that people who strongly believe that they should manage their problems on their own, not show emotions, and not complain about physical discomfort will experience an internal cognitive conflict when faced with a situation that could require help from others. This internal conflict will lead to delays in or avoidance of help seeking, with potentially life-threatening consequences. For example, empirical studies of increasing rates of male suicide in rural Australia have identified hegemonic masculine norms of stoicism as an important causal factor in the context of severe economic stress.57 58 Understanding the influences of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion and other cultural factors on stoic ideologies may help explain past research findings on delays in help seeking. Finally, there may also be positive health consequences of stoic ideologies for individuals,15 which careful prospective research could confirm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the respondents for their voluntary participation in this study. We would particularly like to thank the four peer reviewers of this manuscript, whose detailed and thoughtful readings resulted in a substantially improved final paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: EBP conceived the study. EBP and SW developed the preliminary PW-SIS. All authors enrolled participants and collected questionnaire data. CWW contributed statistical expertise to the confirmatory factor analysis. EBP analysed the data. All authors interpreted the results and outlined the paper. EBP drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to literature review and substantive revisions of the paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Epictetus. Enchiridion. Long G, translator New York: Dover Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aurelius M. Meditations. Long G, translator New York: Dover Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baltzly D. Stoicism : Zalta EN, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2010 edn Palo Alto CA: Stanford University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gowans CW. Medical analogies in buddhist and hellenistic thought: tranquillity and anger. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement; 2010;66:11–33. 10.1017/S1358246109990221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong DB. The meaning of detachment in Daoism, Buddhism, and Stoicism. Dao 2006;5:207–19. 10.1007/BF02868031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker LC. Human health and stoic moral norms. J Med Philos 2003;28:221–38. 10.1076/jmep.28.2.221.14206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stempsey WE. A new stoic: the wise patient. J Med Philos 2004;29:451–72. 10.1080/03605310490503542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore A, Grime J, Campbell P, et al. Troubling stoicism: Sociocultural influences and applications to health and illness behaviour. Health 2013;17:159–73. 10.1177/1363459312451179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sargent C. Between death and shame: dimensions of pain in Bariba culture. Soc Sci Med 1984;19:1299–304. 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90016-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latimer M, Finley GA, Rudderham S, et al. Expression of pain among Mi’kmaq children in one Atlantic Canadian community: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E133–8. 10.9778/cmajo.20130086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Te Karu L, Bryant L, Elley CR. Maori experiences and perceptions of gout and its treatment: a kaupapa Maori qualitative study. J Prim Health Care 2013;5:214–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell JC, Orubuloye IO, Caldwell P. Underreaction to AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Soc Sci Med 1992;34:1169–82. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90310-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarrett T. Warrior Resilience Training in Operation Iraqi Freedom: combining rational emotive behavior therapy, resiliency, and positive psychology. US Army Med Dep J 2008:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarrett TA. Warrior Resilience and Thriving (WRT): Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) as a resiliency and thriving foundation to prepare warriors and their families for combat deployment and posttraumatic growth in operation iraqi freedom, 2005–2009. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 2013;31:93–107. 10.1007/s10942-013-0163-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutnik N, Smith P, Koch T. What does it feel like to be 100? Socio-emotional aspects of well-being in the stories of 16 Centenarians living in the United Kingdom. Aging Ment Health 2012;16:811–8. 10.1080/13607863.2012.684663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waitzkin H, Britt T, Williams C. Narratives of aging and social problems in medical encounters with older persons. J Health Soc Behav 1994;35:322–48. 10.2307/2137213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smiler AP. Thirty years after the discovery of gender: psychological concepts and measures of masculinity. Sex Roles 2004;50:15–26. 10.1023/B:SERS.0000011069.02279.4c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smiler AP. Conforming to masculine norms: evidence for validity among adult men and women. Sex Roles 2006;54:767–75. 10.1007/s11199-006-9045-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, et al. Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psychol Men Masc 2003;4:3–25. 10.1037/1524-9220.4.1.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yong HH. Can attitudes of stoicism and cautiousness explain observed age-related variation in levels of self-rated pain mood disturbance and functional interference in chronic pain patients?. Eur J Pain 2006;10:399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yong HH, Bell R, Workman B, et al. Psychometric properties of the Pain Attitudes Questionnaire (revised) in adult patients with chronic pain. Pain 2003;104:673–81. 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00140-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yong HH, Gibson SJ, Horne DJ, et al. Development of a pain attitudes questionnaire to assess stoicism and cautiousness for possible age differences. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2001;56:P279–P284. 10.1093/geronb/56.5.P279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagstaff GF, Rowledge AM. Stoicism: its relation to gender, attitudes toward poverty, and reactions to emotive material. J Soc Psychol 1995;135:181–4. 10.1080/00224545.1995.9711421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaitniece-Putāne A. Liverpool Stoicism Scale Adaptation. Baltic Journal of Psychology 2005;6:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AR, Yeager AE, Dodd DR. The joint influence of acquired capability for suicide and stoicism on over-exercise among women. Eat Behav 2015;17:77–82. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whealin JM, Kuhn E, Pietrzak RH. Applying behavior change theory to technology promoting veteran mental health care seeking. Psychol Serv 2014;11:486–94. 10.1037/a0037232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witte TK, Gordon KH, Smith PN, et al. Stoicism and sensation seeking: male vulnerabilities for the acquired capability for suicide. J Res Pers 2012;46:384–92. 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 1983;5:168–95. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammond WP, Matthews D, Mohottige D, et al. Masculinity, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays among community-dwelling African-American men. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:1300–8. 10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levant RF, Rankin TJ, Williams CM, et al. Evaluation of the factor structure and construct validity of scores on the Male Role Norms Inventory—Revised (MRNI-R). Psychol Men Masc 2010;11:25–37. 10.1037/a0017637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wheldon CW, Pathak EB. Masculinity and relationship agreements among male same-sex couples. J Sex Res 2010;47:460–70. 10.1080/00224490903100587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:155–64. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabringer LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, et al. Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research. Psychological Methods 1999;4:272–99. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brotherton R, French CC, Pickering AD. Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: the generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Front Psychol 2013;4 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Nooijer J, Puijk-Hekman S, van Assema P. The compensatory health beliefs scale: psychometric properties of a cross-culturally adapted scale for use in The Netherlands. Health Educ Res 2009;24:811–7. 10.1093/her/cyp016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, et al. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:9–22. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. 5th edn San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almberg B, Grafström M, Winblad B. Major strain and coping strategies as reported by family members who care for aged demented relatives. J Adv Nurs 1997;26:683–91. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark AM, Savard LA, Spaling MA, et al. Understanding help-seeking decisions in people with heart failure: a qualitative systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:1582–97. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moloczij N, McPherson KM, Smith JF, et al. Help-seeking at the time of stroke: stroke survivors' perspectives on their decisions. Health Soc Care Community 2008;16:501–10. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caldwell MA, Miaskowski C. Mass media interventions to reduce help-seeking delay in people with symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: time for a new approach? Patient Educ Couns 2002;46:1–9. 10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00153-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lecouturier J, Rodgers H, Murtagh MJ, et al. Systematic review of mass media interventions designed to improve public recognition of stroke symptoms, emergency response and early treatment. BMC Public Health 2010;10:784 10.1186/1471-2458-10-784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luca NR, Suggs LS. Theory and model use in social marketing health interventions. J Health Commun 2013;18:20–40. 10.1080/10810730.2012.688243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Go AS,Mozaffarian D,Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:e28–92. 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zock E, Kerkhoff H, Kleyweg RP, et al. Intrinsic factors influencing help-seeking behaviour in an acute stroke situation. Acta Neurol Belg 2016;116:295–301. 10.1007/s13760-015-0555-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mackintosh JE, Murtagh MJ, Rodgers H, et al. Why people do, or do not, immediately contact emergency medical services following the onset of acute stroke: qualitative interview study. PLoS One 2012;7:e46124 10.1371/journal.pone.0046124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis LL, Mishel M, Moser DK, et al. Thoughts and behaviors of women with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome. Heart Lung 2013;42:428–35. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galdas PM, Johnson JL, Percy ME, et al. Help seeking for cardiac symptoms: beyond the masculine-feminine binary. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:18–24. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitaker KL, Macleod U, Winstanley K, et al. Help seeking for cancer ‘alarm’ symptoms: a qualitative interview study of primary care patients in the UK. Br J Gen Pract 2015;65:e96–105. 10.3399/bjgp15X683533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yousaf O, Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS. A systematic review of the factors associated with delays in medical and psychological help-seeking among men. Health Psychol Rev 2015;9:264–76. 10.1080/17437199.2013.840954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powell W, Adams LB, Cole-Lewis Y, et al. Masculinity and Race-Related Factors as Barriers to Health Help-Seeking Among African American Men. Behav Med 2016;42:150–63. 10.1080/08964289.2016.1165174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nymark C, Mattiasson AC, Henriksson P, et al. The turning point: from self-regulative illness behaviour to care-seeking in patients with an acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:3358–65. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02911.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee H, Bahler R, Chung C, et al. Prehospital delay with myocardial infarction: the interactive effect of clinical symptoms and race. Appl Nurs Res 2000;13:125–33. 10.1053/apnr.2000.7652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evangelista LS, Dracup K, Doering LV. Racial differences in treatment-seeking delays among heart failure patients. J Card Fail 2002;8:381–6. 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baumeister RF. Self and identity: a brief overview of what they are, what they do, and how they work. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011;1234:48–55. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alston M. Rural male suicide in Australia. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:515–22. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alston M, Kent J. The big dry: the link between rural masculinities and poor health outcomes for farming men. J Sociol 2008;44:133–47. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015137supp001.pdf (534.4KB, pdf)