Abstract

Objectives

To identify the effects of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on spinal osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods and design

A cross-sectional study of a nationwide survey was performed.

Setting

This study collected data from the fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2010–2012).

Participants

After excluding ineligible respondents, the total number of participants in this study was 4265 females. Participants were asked to report symptoms and disabilities related to spinal OA. In addition, plain radiographs of the spine were taken of all patients.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Demographic and lifestyle variables were compared between the HRT and non-HRT groups. In addition, radiographic examination and symptom assessment were performed to determine the existence of spinal OA.

Results

Marital status, education, income and HRT were correlated with spinal OA. A risk analysis of related factors showed that HRT and age had effects on spinal OA (ORs 0.717 and 1.257). Nevertheless, in the HRT group, smokers had a increased risk of spinal OA. In addition, the HRT group demonstrated a lower prevalence of spinal OA. The calculated risk for compromised morbidity with HRT compared with the prevalence of spinal OA was 0.717 (OR). The duration of HRT was also related to the risk for spinal OA. The group that had been taking HRT for more than 1 year showed decreased risk (OR 0.686) compared with patients with <1 year of HRT (OR 0.744; P<0.05).

Conclusion

Women receiving HRT showed a lower prevalence of spinal OA. HRT also correlated with a decrease in spinal OA morbidity.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, spine, hormone replacement therapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study analysed a large cross-sectional population and used sophisticated statistical methods, which could enhance the significance of the results.

The study included analysis of demographic and lifestyle variables as well as radiographic examinations and symptom assessment, which could enhance the significance of the results.

The cross-sectional study design precluded establishment of a causal relationship between hormone replacement therapy and osteoarthritis (OA).

More sophisticated diagnostic tools, such as MRI or CT, might be needed to evaluate the precise status of patient joints.

The prevalence or aetiology of OA could also be influenced by ethnic or environmental factors, which could decrease the generalisability of our results.

Introduction

Menopause is a particularly influential period during which women adapt to a new biological state. Women in the postmenopausal period tend to have low oestradiol and serotonin concentrations and a high level of follicle-stimulating hormone.1–4 Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has shown several benefits for elderly females because it minimises symptoms related to oestrogen deficiency.1 3–8 However, few studies have investigated the effects of hormone therapy on the musculoskeletal system. Imada et al performed a case-control study of the influence of oophorectomy on the development of degenerative spondylolisthesis. They reported that the abrupt decrease in oestradiol level caused by oophorectomy could be a predisposing factor in degenerative spondylolisthesis at L4/5.9 Recently, more people have begun experiencing degenerative osteoarthritis (OA), which can occur in several mobile joints of the body, including the spine. We hypothesised that HRT might prevent the onset of degenerative spinal disease and therefore might contribute to the prevention of low back pain.10 11 The objective of this study was to estimate the associations between hormonal factors and spinal OA in a Korean population. We analysed a large cross-sectional population using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) to determine the relationship between HRT and spinal OA.

Methods

Study population

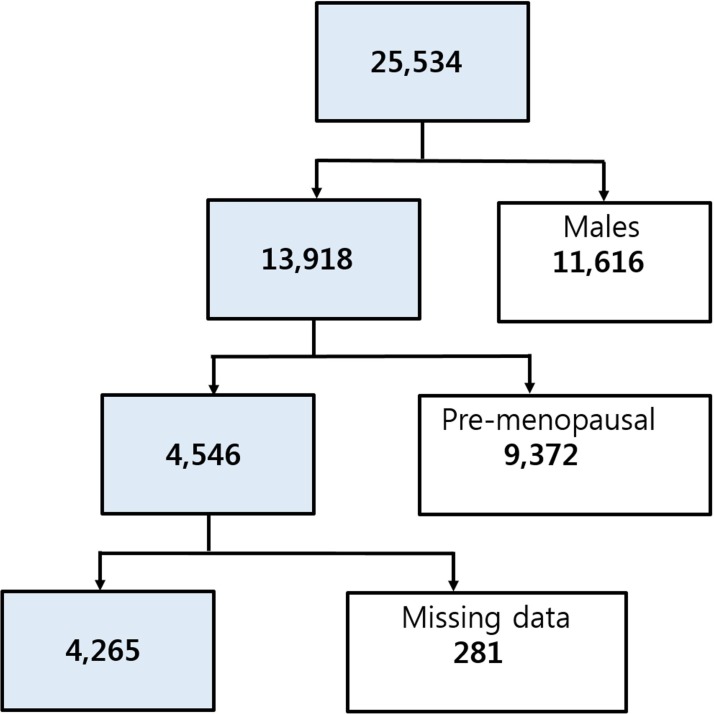

The study design was cross-sectional, using 3 years of data from KNHANES-V (2010–2012), a nationwide health and nutrition survey that is conducted regularly. The KNHANES is conducted annually by the Korean Centers for Disease Control for civilians, and a survey of spine OA was included. The KNHANES is a nationally representative database on health and nutrition, and the subjects were selected from stratified, multistage probability samples of Korean households based on gender, age and geographical area. The number of participants who completed both the health interview and health examination surveys was 25 534 (figure 1). We excluded men (n=11 616), premenopausal women (n=9372) and those with missing data for variables included in the analysis (n=281). The remaining 4265 participants underwent physical and laboratory examinations, including a radiographic examination of the spine. In addition, health interview data were retrieved, including demographic and lifestyle variables. All participants provided informed consent.

Figure 1.

A flow chart showing the inclusion and exclusion of participants according to study criteria.

Radiographic examination and symptom assessment

Anteroposterior and lateral plain radiographic examinations of the lumbar spine were taken using a SD3000 Synchro Stand (Accele Ray, Switzerland). Radiographic changes in each joint were independently assessed by two radiologists using the Kellgren/Lawrence (KL) grading system as follows: grade 0, no visible features of OA, doubtful/questionable osteophytes; grade 1, minimal, definitive small osteophytes and grade 2, definitive moderate osteophytes or subchondral bone cysts and sclerosis with or without foraminal stenosis.12 The presence of radiographic OA was defined as a KL grade of 2 or more. If the grades given by the two radiologists differed, the higher grade was accepted. The concordance rate for KL grades within one grade for the same case was 94.76%. In addition, all patients described their joint-related symptoms (eg, spine), and those symptoms were scored. Participants who reported experiencing arthritic pain for more than one of the past 3 months were asked to report the pain intensity using a numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from 0 to 10, regardless of whether they used medication.

Demographic and lifestyle variables

HRT was defined as use of >1 year of regular hormone medication. Exogenous hormone-related factors included oral contraceptive use duration and HRT starting age and duration. Demographic variables were age, gender, monthly household income, marital status, current residence, education level, smoking status (never smoker, past smoker or current smoker), alcohol consumption (g/day) and physical activity (low, moderate or high). Household income was calculated as the monthly household income divided by the square root of the number of members. Education was classified by years of schooling (<6, 7–9, 10–12 and >12 years). Marital status was stratified into three groups: never married, married and living with spouse and divorced/widowed. Respondents who had smoked >100 cigarettes in their lifetime were classified as smokers and placed into the smoker group. Physical activity was quantified according to the Korean version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Body weight and height were obtained, and the body mass index was calculated by dividing the body weight in kg by the height2 in m2. Waist circumference was measured between the lower costal margin and the iliac crest. We defined obesity as a body mass index ≥25.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS survey procedures (V.9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) in a manner that reflected the sampling weights and provided nationally representative estimates. The characteristics of patients with spinal OA were compared with those of participants without spinal OA using two independent sample t-tests, a one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and Χ2 tests for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate the relationships between parameters.

Results

The relationships between demographic factors and spinal OA

We defined spinal OA as definite OA on plain radiographs with related spinal pain. The mean age of the study population was 64.3±0.2 (50–94) years. The total numbers of participants with spinal OA and HRT were 904 and 588, respectively, out of 4265 total participants. We found no spinal OA in 3361 participants, regardless of HRT status. In terms of demographic factors, marital status, education, income and HRT correlated with a decrease in spinal OA morbidity (table 1). A risk analysis of related factors showed that HRT had significant effects on spinal OA (OR 0.717, table 2). However, in the HRT group, smokers showed a significantly increased risk of spinal OA (OR 11.3) compared with non-smokers (table 3).

Table 1.

Parameter comparison between patients with spinal OA and the control group

| No OA | OA | p Value | |

| n=3361 | n=904 | ||

| Smoking | 6.1% (0.6) | 4.5% (0.9) | 0.1340 |

| Drinking (heavy) | 0.5% (0.2) | 0.3% (0.2) | 0.4693 |

| High activity | 15.1% (0.8) | 12.1% (1.3) | 0.0608 |

| Urban residence | 71.0% (2.4) | 69.6% (3.0) | 0.5131 |

| With spouse | 67.7% (1.1) | 58.3% (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| High education | 22.0% (1.0) | 14.7% (1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Low income | 33.9% (1.1) | 42.8% (2.0) | <0.0001 |

| Contraception | 21.2% (0.9) | 21.6% (1.6) | 0.8115 |

| HRT | 13.5% (0.7) | 8.2% (1.1) | 0.0002 |

| BMI ≥25 | 24.2% (0.1) | 24.4% (0.1) | 0.0593 |

| WC ≥85 | 82.3% (0.2) | 83.0% (0.3) | 0.0673 |

An age-adjusted logistic regression model was used.

Bold text means statistical significance (P<0.05).

BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); HRT, hormone replacement therapy; N, number in a group; OA, osteoarthritis; WC, waist circumference (cm).

Table 2.

Risk analysis of spinal OA with other related factors

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age | 1 | ||

| Smoking | 0.711 | 0.454 to 1.114 | 0.1367 |

| Drinking (heavy) | 0.853 | 0.220 to 3.308 | 0.8182 |

| High activity | 0.892 | 0.676 to 1.178 | 0.4197 |

| Urban residence | 1.077 | 0.870 to 1.332 | 0.4960 |

| With spouse | 1.031 | 0.837 to 1.269 | 0.7746 |

| High education | 0.912 | 0.693 to 1.201 | 0.5127 |

| Low income | 0.999 | 0.816 to 1.222 | 0.9889 |

| Contraception | 1.037 | 0.838 to 1.283 | 0.7359 |

| HRT | 0.717 | 0.527 to 0.976 | 0.0344 |

| BMI ≥25 | 1.094 | 0.926 to 1.291 | 0.2920 |

| WC ≥85 | 0.975 | 0.811 to 1.172 | 0.7884 |

An age-adjusted logistic regression model was used.

Bold text means statistical significance (P<0.05).

BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); HRT, hormone replacement therapy; OA, osteoarthritis; WC, waist circumference (cm).

Table 3.

Prevalence and risk analysis for spinal OA with smoking in the HRT group

| Non-smokers | Smokers | p Value | |

| Spine OA | 83.5% (1.8) | 98.4% (1.7) | 0.025 |

| ORs | 1 | 11.32 (1.31–17.90) | 0.027 |

Bold text means statistical significance (P<0.05).

Age, BMI, WC, drinking and exercise were adjusted.

BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); HRT, hormone replacement therapy; OA, osteoarthritis; WC, waist circumference (cm).

Relationship between HRT and spinal OA

The HRT group had a lower prevalence of spinal OA. In addition, the spinal OA group showed a significantly lower rate of HRT (table 4). Calculated risks for compromised morbidity were 0.717 (OR) compared with the control group (table 5). The solitary radiographic spinal OA and solitary symptom groups also showed a lower percentage of HRT than controls (OR 0.723 and 0.916, respectively); however, the radiographic OA plus symptom group had the lowest percentage of HRT and significantly higher morbidity (OR 0.717). The duration of HRT was also related to the risk of spinal OA: the >1 year of medication group had a significantly decreased risk (OR 0.686) compared with the <1 year of medication group (OR 0.840).

Table 4.

The prevalence of hormone therapy according to spinal pain and radiographic OA

| No HRT | HRT | p Value | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| OA | |||||

| Grade 0 | 696 | 19.8 (1.0) | 184 | 30.2 (2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Grade 1 | 1454 | 40.8 (1.0) | 253 | 46.5 (2.5) | |

| Grade 2 | 1527 | 39.4 (1.1) | 151 | 23.3 (2.1) | |

| Sx | 1302 | 34.7 (1.1) | 162 | 26.0 (2.2) | 0.0005 |

| OA+Sx | 819 | 21.0 (1.1) | 85 | 13.1 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

An age-adjusted logistic regression model was used.

Bold text means statistical significance (P<0.05)

HRT, hormone replacement therapy; OA, osteoarthritis; OA, participants with only radiological findings; OA+Sx, participants with both symptoms and radiological findings; Sx, participants with only symptoms.

Table 5.

Risk analysis of spinal OA with hormone therapy

| HRT | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| OA | 0.723 | 0.563 to 0.929 | 0.011 |

| Sx | 0.916 | 0.723 to 1.159 | 0.464 |

| OA+Sx | 0.717 | 0.527 to 0.976 | 0.034 |

An age-adjusted logistic regression model was used.

Bold text means statistical significance (P<0.05).

HRT, hormone replacement therapy; OA, osteoarthritis; OA, participants with only radiological findings; OA+Sx, participants with both symptoms and radiological findings; Sx, participants with only symptoms.

Discussion

OA involves degenerative changes in soft tissue, subchondral bone and hyaline cartilage that lead to serious joint disability.5 13–17Oestrogen deficiency is related to the occurrence and progression of OA. Beginning in early menopause, the number of women who suffer from OA increases dramatically.1–6 13 18 19 The association between oestrogen and OA has been verified in a murine model, and research on both oestrogen deficiency and complement in articular cartilage has been conducted in animal models.20 In many experimental animal studies, ovariectomy was reported to induce OA, whereas oestrogen complement delayed cartilage degeneration.6 8 21–24 Oestrogens act on oestrogen receptors distributed throughout the articular cartilage, synovial membrane and ligaments and are thought to be related to degenerative changes. In addition, Gruber et al suggested the expression and localisation of oestrogen receptor-beta in the annulus cells of human intervertebral discs. They provided evidence of oestrogen beta gene expression in human intervertebral disc cells in vivo and in vitro. Culturing annulus cells in the presence of 17-beta-oestradiol significantly increased cell proliferation.25 Baron et al investigated the effects of menopause and HRT on the intervertebral discs and reported that oestrogen-replete women appear to maintain higher intervertebral discs than untreated postmenopausal women.26 Moreover, patients receiving long-term HRT have a lower risk of knee and hip OA on plain radiographs than women who do not take HRT.2 3 5 16 20

In this study, age, marital status, education level and income all significantly correlated with OA morbidity. However, BMI and body composition factors were not associated with spinal OA. Previous studies have reported that joint pain is associated with several sociodemographic factors, such as gender, advanced age, low education level, smoking and occupation.10 15 In particular, we found significant relationships between factors in the female group and higher prevalence of OA. It appears that the female population is more prone to OA, and this association could be related to hormonal influences, especially in an elderly population. Wang et al reported increased low back pain prevalence in females than males, especially after menopause. They reported that higher low back pain prevalence in school age girls compared with school age boys is likely caused by psychological factors, female hormone fluctuation and menstruation. Compared with young and middle-aged subjects, a further increase in low back pain prevalence in females compared with males was noted after menopause.27 In our study, the HRT group showed a significantly lower prevalence of spinal OA. We therefore assume that HRT can influence the prevalence of spinal OA. We found a positive, long-term effect of HRT, suggesting that oestrogen deficiency could be a cause of OA and highlighting the need for further studies on the effects of oestrogen on cartilage and bone. Although we could not determine cause and effect relationships, HRT might prevent OA. We hypothesised that HRT has a protective effect on the development of spinal OA. In accordance with our hypothesis, both spinal pain and prevalence of radiographic spinal OA were lower in the HRT group. The duration of hormonal therapy also showed a significant relationship with prevalence of spinal OA, which suggests the importance of continuous HRT in elderly females.

In the present study, smoking was not significantly related to spinal OA morbidity, but it was correlated with an increased prevalence of spinal OA, especially in the HRT group. However, the association between the risk of OA and smoking is still unclear. Some studies have reported that smoking is a protective factor against severe OA. In contrast, observational studies have concluded that smoking has no protective effect on the progression of OA.7 26 28–34 In any case, smokers prescribed HRT showed a significantly increased risk of OA compared with non-smokers taking HRT, even though the use of HRT had an overall protective effect against OA. These data show that smoking could have a hazardous effect on joint cartilage that could eliminate the protective effect of HRT for OA.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional study design prevented us from establishing causal relationships between HRT and OA. In this study, we could not match the OA site and spinal pain origin. We used a cross-sectional nationwide health survey with a brief health interview regarding pain related to each joint (eg, hip, knee and spine). Therefore, we could not clarify the relationship between spinal OA and pain with a spinal origin. Future prospective studies will be required to determine causal relationships. Second, the use of a single 11-point NRS did not allow us to evaluate the exact intensity of the respondents’ acute and chronic pain, including functional impairment. In addition, more sophisticated diagnostic tools, such as MRI or CT, might be needed to evaluate the precise status of patient joints. Third, the prevalence and aetiology of OA might be influenced by ethnic or environmental factors, which could decrease the generalisability of our study. In addition, the relatively small number of smokers in the HRT group could dilute the significance of that result. Despite these limitations, our study analysed a large cross-sectional population and used sophisticated statistical methods. We found a significantly lower prevalence of spinal OA in patients receiving HRT. We believe that our results will be helpful to physicians treating OA.

In conclusion, populations receiving HRT showed a significantly lower prevalence of spinal OA, and the duration of HRT was significantly related to spinal OA prevalence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to sections (1), (2) and (3) described below: (1) study conception and design, data acquisition or data analysis and interpretations: J-HP, J-YH. (2) Drafting of the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: KH, S-WH. (3) Final approval of the version to be submitted: EMC, J-YH.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Review Board approved this study (2010-02CON-21-C, 2011-02CON-06-C, 2012-01EXP-01–2C).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES-V: 2010–2012) data are available to any researchers under approval of an IRB.

References

- 1.Anon. Effects of hormone therapy on bone mineral density: results from the postmenopausal estrogen/progestin interventions (PEPI) trial. The writing group for the PEPI. JAMA 1996;276:1389–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wluka AE, Davis SR, Bailey M, et al. Users of oestrogen replacement therapy have more knee cartilage than non-users. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:332–6. 10.1136/ard.60.4.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torgerson DJ, Bell-Syer SE. Hormone replacement therapy and prevention of nonvertebral fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 2001;285:2891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spector TD, Nandra D, Hart DJ, et al. Is hormone replacement therapy protective for hand and knee osteoarthritis in women?: The Chingford Study. Ann Rheum Dis 1997;56:432–4. 10.1136/ard.56.7.432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandmark H, Hogstedt C, Lewold S, et al. Osteoarthrosis of the knee in men and women in association with overweight, smoking, and hormone therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58:151–5. 10.1136/ard.58.3.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt IU, Wakley GK, Turner RT. Effects of estrogen and progesterone on tibia histomorphometry in growing rats. Calcif Tissue Int 2000;67:47–52. 10.1007/s00223001096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrich W, Haitel A, Holzer G, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta is the predominant estrogen receptor subtype in normal human synovia. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2006;13:512–7. 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sniekers YH, Weinans H, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Animal models for osteoarthritis: the effect of ovariectomy and estrogen treatment: a systematic approach. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:533–41. 10.1016/j.joca.2008.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imada K, Matsui H, Tsuji H. Oophorectomy predisposes to degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995;77:126–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marty-Poumarat C, Ostertag A, Baudoin C, et al. Does hormone replacement therapy prevent lateral rotatory spondylolisthesis in postmenopausal women? Eur Spine J 2012;21:1127–34. 10.1007/s00586-011-2048-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang YXJ. Menopause as a potential cause for higher prevalence of low back pain in women than in age-matched men. J Orthop Translat 2017;8:1–4. 10.1016/j.jot.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957;16:494–502. 10.1136/ard.16.4.494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, et al. The incidence and natural history of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1500–5. 10.1002/art.1780381017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwer GM, van Tol AW, Bergink AP, et al. Association between valgus and varus alignment and the development and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1204–11. 10.1002/art.22515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence JS, Bremner JM, Bier F. Osteo-arthrosis. Prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis 1966;25:1–24. 10.1136/ard.25.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson MG, Michet CJ, Ilstrup DM, et al. Idiopathic symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a population-based incidence study. Mayo Clin Proc 1990;65:1214–21. 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)62745-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAlindon TE, Snow S, Cooper C, et al. Radiographic patterns of osteoarthritis of the knee joint in the community: the importance of the patellofemoral joint. Ann Rheum Dis 1992;51:844–9. 10.1136/ard.51.7.844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1701–12. 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ham KD, Loeser RF, Lindgren BR, et al. Effects of long-term estrogen replacement therapy on osteoarthritis severity in cynomolgus monkeys. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1956–64. 10.1002/art.10406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang JH, Kim JH, Lim DS, et al. Effect of combined sex hormone replacement on bone/cartilage turnover in a murine model of osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Surg 2012;4:234–41. 10.4055/cios.2012.4.3.234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvo E, Castañeda S, Largo R, et al. Osteoporosis increases the severity of cartilage damage in an experimental model of osteoarthritis in rabbits. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:69–77. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arts J, Kuiper GG, Janssen JM, et al. Differential expression of estrogen receptors alpha and beta mRNA during differentiation of human osteoblast SV-HFO cells. Endocrinology 1997;138:5067–70. 10.1210/endo.138.11.5652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Høegh-Andersen P, Tankó LB, Andersen TL, et al. Ovariectomized rats as a model of postmenopausal osteoarthritis: validation and application. Arthritis Res Ther 2004;6:R169–80. 10.1186/ar1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Räsänen T, Messner K. Articular cartilage compressive stiffness following oophorectomy or treatment with 17beta-estradiol in young postpubertal rabbits. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:357–62. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruber HE, Yamaguchi D, Ingram J, et al. Expression and localization of estrogen receptor-beta in annulus cells of the human intervertebral disc and the mitogenic effect of 17-beta-estradiol in vitro. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2002;3:4 10.1186/1471-2474-3-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baron YM, Brincat MP, Galea R, et al. Intervertebral disc height in treated and untreated overweight post-menopausal women. Hum Reprod 2005;20:3566–70. 10.1093/humrep/dei251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wáng YX, Wáng JQ, Káplár Z. Increased low back pain prevalence in females than in males after menopause age: evidences based on synthetic literature review. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2016;6:199–206. 10.21037/qims.2016.04.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshioka T, Sato B, Matsumoto K, et al. Steroid receptors in osteoblasts. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980;148:297–303. 10.1097/00003086-198005000-00047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart DJ, Spector TD. Cigarette smoking and risk of osteoarthritis in women in the general population: the Chingford study. Ann Rheum Dis 1993;52:93–6. 10.1136/ard.52.2.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearce F, Hui M, Ding C, et al. Does smoking reduce the progression of osteoarthritis? Meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1026–33. 10.1002/acr.21954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mnatzaganian G, Ryan P, Reid CM, et al. Smoking and primary total hip or knee replacement due to osteoarthritis in 54,288 elderly men and women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:1471–2474. 10.1186/1471-2474-14-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schouten JS, van den Ouweland FA, Valkenburg HA. A 12 year follow up study in the general population on prognostic factors of cartilage loss in osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis 1992;51:932–7. 10.1136/ard.51.8.932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gullahorn L, Lippiello L, Karpman R. Smoking and osteoarthritis: differential effect of nicotine on human chondrocyte glycosaminoglycan and collagen synthesis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:942–3. 10.1016/j.joca.2005.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies-Tuck ML, Wluka AE, Forbes A, et al. Smoking is associated with increased cartilage loss and persistence of bone marrow lesions over 2 years in community-based individuals. Rheumatology 2009;48:1227–31. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.