Abstract

Objectives

It is the aim of the current research to identify some common functionalities of postnatal application, and to determine the quality of the information content of postnatal depression application using validated scales that have been applied for applications in other specialties.

Settings and participants

To determine the information quality of the postnatal depression smartphone applications, the two most widely used smartphone application stores, namely Apple iTunes as well as Google Android Play store, were searched between 20May and 31 May. No participants were involved. The inclusion criteria for the application were that it must have been searchable using the keywords ‘postnatal’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘perinatal’, ‘postpartum’ and ‘depression’, and must be in English language.

Intervention

The Silberg Scale was used in the assessment of the information quality of the smartphone applications.

Primary and secondary outcomes measure

The information quality score was the primary outcome measure.

Results

Our current results highlighted that while there is currently a myriad of applications, only 14 applications are specifically focused on postnatal depression. In addition, the majority of the currently available applications on the store have only disclosed their last date of modification as well as ownership. There remain very limited disclosures about the information of the authors, as well as the references for the information included in the application itself. The average score for the Silberg Scale for the postnatal applications we have analysed is 3.0.

Conclusions

There remains a need for healthcare professionals and developers to jointly conceptualise new applications with better information quality and evidence base.

Keywords: postnatal depression, silberg scale, mhealth

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We have made use of a comprehensive search strategy to characterise the functionalities of the postnatal applications that are currently available on the two most popular application stores.

We have applied the Silberg Scale, which is a validated information quality scale, in the assessment of the information quality of postnatal applications

We have identified several gaps in information quality, which clinicians and researchers need to be cognisant of

We have not evaluated the applications for their levels of engagement and aesthetics.

Introduction

The WHO, in its latest report, has highlighted that approximately 10% of mothers suffer from depression during their pregnancy.1 Postnatally, the figures for depression increase to 13%.1 The WHO has pointed out that the prevalence of depression varies in accordance to the regions, with low-income and middle-income countries having a higher prevalence of postnatal depression (PND).1 Some of the core symptoms in PND include that of low mood, marked reduction in self-esteem, loss of interest and enjoyment, as well as tearfulness. Some women also report of hopelessness as well as excessive fatigue.2 In addition, it is also not uncommon for mothers to report of increased anxiety with regard to their baby’s well-being.2 Such anxiety symptoms might in turn result in a diminished affection for their baby as well as breast feeding-related difficulties.2 It is essential for PND to be screened for and detected early, given that untreated PND does have consequential effects for mothers themselves and for their newborns. Clearly, PND could increase the risk of new mothers harming themselves or their children if they are severely depressed, or if they have had symptoms of psychotic depression. For the newborn, there have been recent studies that have highlighted how the postpartum bonding could be adversely affected due to the presence of depressive symptoms in a new mother.3 The poor postpartum bonding could also result in consequential attachment issues in the newborn, which could be carried into adulthood.3 In particular, newborns tend to have insecure attachment to their parental figures. Aside from attachment-related issues, children born of mothers with underlying PND do commonly have resultant cognitive issues,4 as well as language and expressive issues. Other longitudinal studies conducted have demonstrated that PND has a consequential impact on the well-being of children.5

From a public policy perspective, PND and its associated morbidity and mortality would lead to a tremendous burden in healthcare. Studies have been conducted in the UK, which have shown that PND has on the average led to a massive reduction in earnings and a reduction in the health-related quality of life.6 Hence, there is a need for early identification and various interventions for treatment. Based on the recommendations of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, there are different approaches to deal with the issue of PND, and the main determinant for this would be that of the severity of the depressive symptoms. Based on the stepped care recommendations of the NICE guidelines, women with subthreshold levels of depression could receive self-help programmes.7 However, psychological-based treatment, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, along with medications would be recommended for mothers diagnosed with mild to moderately severe PND.7 Medications that are indicated for the treatment of PND include tricyclic antidepressants as well as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.7 For mothers with severe depression, who are clearly at risk to either themselves or to their baby, inpatient admission and treatment would be recommended and would be warranted. It is of importance to recognise that the NICE guidelines7 recommend the provision of pertinent information related to mental health to all women of childbearing potential. Information provision to postnatal mothers is of utmost importance as prior research has highlighted that there was a correlation with the amount of prenatal and postnatal health information provided and the subsequent scores on the depressive scale.8 There has also been research highlighting the importance of prenatal education in ensuring that women receive information about PND.9

In the recent years, technology has become an integral part of healthcare. e-Health (electronic health) as well as m-health (mobile health) are increasingly being used as tools for healthcare. There have been recent studies that have highlighted that new mothers and those who are suffering from PND are interested in the utilisation of a health application.10 These findings are of significance, as it would mean that new mothers are not averse to the usage of technology in helping them manage their mood-related symptoms and conditions. Clearly, one of the major challenges faced by all new mothers is that of time management, and setting time aside for a medical consultation might be difficult. In addition, in some countries like Australia and Canada, there might be geographical barriers that prevent these new mothers from seeking the appropriate help. To date, there has been quite a few trials evaluating the potential primarily of e-health in supporting new mothers with PND. Lee et al11 recently conducted a systematic review and have highlighted that e-health is indeed a feasible option and a cost-effective solution. However, there remains a paucity of research studies evaluating the potential of m-health and smartphone applications for PND. Most of the published research to date have highlighted how these tools are useful for healthcare workers in the low-income and middle-income countries, and the existing tools only provide basic psychoeducational information.12

Zhang et al13 have previously highlighted the importance of healthcare professionals’ involvement in the conceptualisation of smartphone-based interventions. More importantly, Hollis et al13 have also highlighted the need for current applications to be further evaluated in terms of their informational contents using validated scales. Such an analysis is critical, given that there is a myriad of other postnatal applications on the application stores. In addition, prior research done on obesity applications14 as well as cardiovascular applications15 has highlighted that there are several shortcomings inherent in the applications currently available on the application store.

Given this, it is the main aim of the current research to determine the quality of the information content of postnatal application using validated scales that have been applied for applications in other specialties. It is also the secondary aim of the current research to systematically characterise some of the common functionalities of postnatal applications.

Methodology

Selection of smartphone applications

To determine the information quality of the PND smartphone applications, the two most widely used smartphone application stores, namely Apple iTunes as well as Google Android Play store, were searched between 20 May 2017 and 31 May 2017.

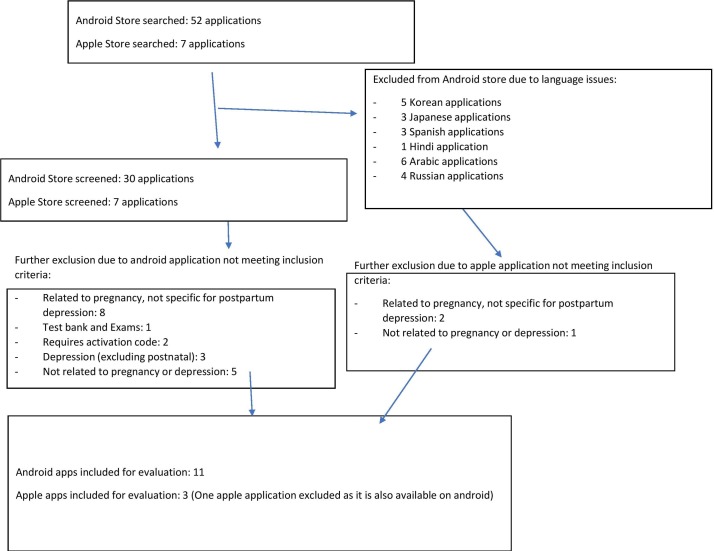

The following keywords were used in the search strategy: ‘postnatal’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘perinatal’, ‘postpartum’ and ‘depression’. The search yielded a cumulative total of 59 applications, with 52 applications from the Google Android store and 7 applications from the Apple iTunes store. Eighteen applications were excluded from the Android store as they were not in English language and the authors have had difficulties with evaluation of these applications given the language barriers. After reviewing the description of the applications, a cumulative total of 22 applications were excluded as they were of no relevance. The details for the exclusion of these applications are included in figure 1. If both a free and a paid version were available on the store, both versions were downloaded for further evaluation. Any duplicated smartphone applications were removed. If a duplicated version of an application was offered on both platform, only one version (that on the Android platform) would be downloaded for further evaluation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the selection process of smartphone applications related to postnatal care.

Each of the respective applications was downloaded on either an Apple iPhone 6s device (for the Apple platform running iOS operating system 10.1) or on a Xiaomi Note 3 (for the Android platform running Android Marshmallow operating system). At the end, a total of 14 applications were included for the evaluation of their underlying information quality. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process for the smartphone applications.

Analysis of the information quality of smartphone applications

To date, there remains no standardised scale that has been recommended by any guidelines for the assessment of application quality as well as for the analysis of the information quality of smartphone applications. Hence, the authors have decided to make use of the 9-point Silberg Scale,16 which was initially developed by Griffiths and Christensen16 and have been extensively used to determine the quality of information furnished via online websites16 as well as the quality of information inherent in smartphone applications.16 Notably, the same scale has been recently used by researchers in the analysis of the information quality of bariatric applications as well as cardiovascular applications.14 15 The Silberg Scale takes into consideration the domains illustrated in table 1. The total cumulative score possible is 9 points and a higher score is indicative of better information quality.

Table 1.

Categories for assessment of information quality based on the Silberg Scale

| Categories for assessment of information quality | Individual subscale items |

| Authorship |

|

| Attribution of information sources |

|

| Disclosure |

|

| Currency |

|

| Cumulative total score | 9 points |

Methodology of scoring and assessment

The first author MWBZ and authors AL and TW were involved in the extraction of the relevant information and the initial analysis and scoring of each of the respective applications. If there were any disagreements among the authors, it was resolved with discussion.

Data analysis

The data collated were analysed using descriptive statistics. The frequency, mean and SD were computed based on the scores acquired from the Silberg Scale.

Results

Core characteristics of PND applications

A cumulative total of 14 applications were included for analysis. Table 2 provides an overview of the applications that were identified and further analysed. Table 2 also summarises the core characteristics of the applications.

Table 2.

Core functionalities of postnatal depression application that are included in the current analysis

| Name of applications | Platform | General description | Silberg score |

| Anxiety and Depression Scales | Android | Includes questionnaire for the evaluation of depression and anxiety | 3 |

| Self Help | Android | Includes leaflets about various mental health disorders | 7 |

| Pregnancy Week by Week | Android | Guide to conception, pregnancy, taking care of baby and being a parent | 2 |

| Mental Health Assessments | Android | Includes sets of common questionnaires for assessment of various psychiatric disorders | 2 |

| Baby Care Week by Week: Tips | Android | Baby development week by week and parenting tips in one baby application; contains information, audio and video about postnatal depression | 2 |

| First Time Moms | Android | Pregnancy guide and information about how to deal with postpartum depression | 3 |

| New Baby New Life | Android/Apple | Podcasts focusing on hypnosis for postnatal depression | 1 |

| GoMum | Android | Cognitive behavioural therapy-based activities and information about postpartum depression | 4 |

| Postnatal Yoga | Android | Yoga exercises for postnatal mothers who are suffering from postnatal depression or anxiety | 2 |

| Bump 2 Breast | Android | Information about child caring as well as postpartum depression | 3 |

| Your Personal Health | Android | Collection of surveys and assessment | 2 |

| What Were We Thinking | Apple | Educational information with videos and functions for postnatal depression | 5 |

| Essential Baby Care Guide | Apple | Educational information covering topics such as feeding, sleeping, care and development, and first aid skills in the form of videos; also contains video about postnatal depression | 3 |

| PPD Screening | Apple | Includes the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to evaluate for depressive symptoms | 3 |

Information quality analysis

For the 14 applications, the average Silberg score was 3.0 with an SD of 1.52, out of a total score of 9 points. Eight out of the total of 14 applications have a score that is greater than or equal to the mean score of 3.0. All the applications (100.0%) have disclosed the date of creation or last modification, but none of the applications have highlighted the last date of modification of the application. Most of the applications have disclosed the ownership of the applications (93.9%). Only 28.6% of the identified applications have provided references for the information they have included.

The current gaps in the information quality pertain to the currency of the application (whether there have been any modifications in the past month) (0.0), as well as the disclosure of the affiliations (0.143), identification of the authors (0.143) and credentials of the authors (0.071). In addition, a good proportion of the applications also did not disclose whether there are sponsorships for the application (0.071). Table 3 provides a summary of the mean scores for each of the individual categories, as well as the mean percentage of applications fulfilling each of the criteria.

Table 3.

Mean scores on the individual subitems on the Silberg Scale

| Category | Mean scores | SD |

| Authorship—identification of authors | 0.143 | 0.363 |

| Authorship—affiliations of authors | 0.143 | 0.363 |

| Authorship—credentials of authors | 0.071 | 0.267 |

| Attribution—sources | 0.286 | 0.469 |

| Attribution—provision of reference | 0.286 | 0.469 |

| Disclosure—ownership of applications | 0.929 | 0.267 |

| Disclosure—sponsorship | 0.071 | 0.267 |

| Currency—modification within the past month | 0.0 | 0 |

| Currency—disclosure of date of last modification | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Average Silberg score | 3.0 | 1.52 |

Discussion

This is perhaps one of the first studies that have been conducted to date that look at the information quality of PND smartphone applications. To date, there have only been systematic reviews about e-health innovations for PND. There remains a lack of analysis about the information quality of smartphone-based PND applications. Our search revealed that only a limited number of applications (n=14) contain information or have functionalities related to PND, among the myriad of applications yielded when we initially applied our search strategy. Our current research highlighted that the average Silberg score for postnatal applications was 3.0, with an SD of 1.52. Eight out of the cumulative total of 14 applications scored more than or equal to the average score. While the vast majorities of the applications have provided information about creation dates and ownership of applications, only a limited number has furnished information pertaining to the references for the information shared within the application. Prior studies have used the same scale for cardiovascular applications and the average score was 2.87.15 Other studies have used the scale for obesity applications and the average score was 4.0.14 There are commonalities in the domains in which information is deemed to be lacking. Zhang et al14 reported that among the 39 obesity applications sampled, the vast majorities did not provide information about references, full disclosure of sponsorship and whether the application has been modified in the last month. Xiao et al15 have also reported similar findings.

Based on the current review, it is obvious that most of the applications are lacking in several aspects and hence the resultant low scores on the Silberg Scale. It is of importance that smartphone applications contain appropriate information, and that they do need to have appropriate references as well as cite the authors responsible for the creation of the informational contents. This is especially important for postnatal-related applications, as these applications do frequently provide information for the new mothers and information relating to the care of their newborn babies. Zhang et al13 have previously proposed and highlighted the importance of having healthcare professionals in the joint conceptualisation of smartphone applications, as well as having a governmental regulatory body to help in the assessment of applications that are deemed safe and reliable for the public to use. From our knowledge, the Royal College of Psychiatrists is one of the organisations that have provided the public with mental health leaflets (both in print and online version) that are carefully curated in terms of information quality. The College has been successful in doing so by ensuring that there is a group of experts to draft as well as to provide periodic timely updates to the mental health leaflets, to ensure that the information is kept current as well as accurate. This strategy is perhaps how the College has been granted the UK’s information safety standards for the information they have included in their leaflets for dissemination to the public.

Zhang et al14 in their previous analysis of the information quality of bariatric-related applications have highlighted several reasons for the lack of provision of references for the information sources. The authors previously pointed out how variations in screen size might result in technical difficulties with the integration of reference sources. However, with the recent advances in smartphone application development, especially with the usage of cross-platform programming techniques, this issue could potentially be overcome, as the newer programming techniques would ensure the compatibility of the application across a myriad of varying devices as well as screen sizes. In addition, one of the reasons as to why most of the applications have not been updated recently nor indicated a date of last update has to do much with the way the applications have been developed. Most of the current conceptualisations rely heavily on coding informational content within the application, and hence updating the contents within the application would be an issue. In the conceptualisation of further applications, it would be recommended for application developers and healthcare professionals to jointly consider the integration of a dynamic content management system, such that the information contents within the application could be updated in real time and kept current.

In our current study, we have managed to identify some of the core functionalities of postnatal applications. Most of the identified applications are limited to the provision of pregnancy-related information and psychoeducational information to new mothers. Several of these applications provide validated screening tools for the assessment of postnatal depressive symptoms. To our knowledge, there has only been one application that has included a cognitive behavioural therapy component as an intervention. From a clinical perspective, it would be helpful if there are more applications that have included a therapeutic component within the application.

One of the major strengths of the current study is that we managed to make use of a validated scale to evaluate the information quality of PND applications that are currently available on application stores. The usage of the scale has enabled us to determine the limitations in the information quality. In addition, as the same scale has also been used in the evaluation of other applications from other disciplines, we are able to compare and elucidate the common issues underlying the gaps in information quality across a spectrum of applications. The findings would be of relevance to regulatory bodies who are planning for policies involving smartphone applications. Despite the strengths, there are several limitations to the current study. In our current study, the applications are identified via either the Apple or the Android application stores. While these are the two most common application stores, there might be very different applications available on other platforms that we have not evaluated. In addition, we have limited the search strategy to applications that are in English language. We do acknowledge that there are multiple applications in other languages such as Spanish. While the authors have extracted the applications from the store over a duration of 1 month, with the rapid development of smartphone applications using new technologies of cross-platform programming, it is not unexpected that new applications deployed onto the store after the period of evaluation are not considered. The Silberg Scale might have well been validated across several studies for the evaluation of information quality, but it is not specific for information quality for smartphone applications and does not cover and assess for other aspects of the smartphone application, such as usability and levels of engagement. More recently, researchers have proposed the utilisation of the Mobile Application Rating Scale17 for the evaluation of smartphone applications. While the Mobile Application Rating Scale appears to be comprehensive, one of the concerns the authors have is that there are only four questions looking into the information quality, which asked only about the quality, quantity, visual presentation and credibility of sources.

Conclusions

PND has an impact on the well-being of new mothers as well as their offspring, and hence it is clearly a disorder of importance that warrants early screening and intervention. e-Health has been demonstrated to be efficacious, and there are m-health technologies deployed in low-income and middle-income countries that have been evaluated by research. However, there remains a myriad of postnatal applications on application stores. It is pertinent for us to determine the contents within these applications, as well as apply validated scales to assess their information quality. Like the bariatric and cardiovascular applications, there remains a paucity of disclosures in various domains. Further conceptualisations and research on postnatal m-health technologies should target these areas identified in the current review.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Study conceptualisation: MWBZ, SWCC, RCMH jointly conceptualised the existing study. Data extraction: MWBZ, AL, TW assisted in the extraction of the data from the application stores. Data analysis: MWBZ, AL, TW were involved in the initial analysis, and RCMH provided guidance with the analysis. Initial draft: MWBZ, AL, TW, SWCC, OW, RCMH jointly wrote up the initial draft of the manuscript. Second revision: DSSF and JC provided guidance for the second revision. The second revision of the manuscript was undertaken by MWBZ and RCMH. The third revision of the manuscript was undertaken by MWBZ. All authors have proofread the manuscript prior to submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data used for preparation of this manuscript have been included within the manuscript.

References

- 1.Maternal Mental Health. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/ (assessed 1 Dec 2016)

- 2.Puri BK, Hall A, Ho R. Revision Notes in Psychiatry. London, UK: CRC Press, 2014:564–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nonnenmacher N, Noe D, Ehrenthal JC, et al. . Postpartum bonding: the impact of maternal depression and adult attachment style. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016;19:927–35. 10.1007/s00737-016-0648-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Kaaya S, Chai J, et al. . Maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2017;47:680–9. 10.1017/S003329171600283X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korhonen M, Luoma I, Salmelin R, et al. . A longitudinal study of maternal prenatal, postnatal and concurrent depressive symptoms and adolescent well-being. J Affect Disord 2012;136:680–92. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer A, Pawlby S, Plant DT, et al. . Perinatal depression and child development: exploring the economic consequences from a South London cohort. Psychol Med 2015;45:51–61. 10.1017/S0033291714001044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Postnatal Depression Guideline. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192/chapter/1-Recommendations (accessed 22 Nov 2016)

- 8.Youash S, Campbell MK, Campbell K, et al. . Influence of health information levels on postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 2013;16:489–98. 10.1007/s00737-013-0368-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farr SL, Denk CE, Dahms EW, et al. . Evaluating universal education and screening for postpartum depression using population-based data. J Womens Health 2014;23:657–63. 10.1089/jwh.2013.4586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osma J, Barrera AZ, Ramphos E. Are pregnant and postpartum women interested in health-related apps? Implications for the prevention of perinatal depression. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2016;19:412–5. 10.1089/cyber.2015.0549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee EW, Denison FC, Hor K, et al. . Web-based interventions for prevention and treatment of perinatal mood disorders: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:38 10.1186/s12884-016-0831-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amoakoh-Coleman M, Borgstein AB, Sondaal SF, et al. . Effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeting health care workers to improve pregnancy outcomes in low- and middle-income Countries: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e226 10.2196/jmir.5533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang MWB, Ho CSH, Cheok CCS, et al. . Smartphone apps in mental healthcare: the state of the art and potential developments. BJPscyh Advances 2015;21:354–8. 10.1192/apt.bp.114.013789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang MW, Ho RC, Hawa R, et al. . Analysis of the information quality of bariatric surgery smartphone applications using the silberg scale. Obes Surg 2016;26:163–8. 10.1007/s11695-015-1890-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Q, Lu S, Wang Y, et al. . Current status of cardiovascular Disease-related smartphone apps downloadable in China. Telemed J E Health 2017;23:219–25. 10.1089/tmj.2016.0083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Quality of web based information on treatment of depression: cross sectional survey. BMJ 2000;321:1511–5. 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domnich A, Arata L, Amicizia D, et al. . Development and validation of the Italian version of the mobile application rating scale and its generalisability to apps targeting primary prevention. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:83 10.1186/s12911-016-0323-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.