Abstract

Objectives

BRIGHTLIGHT is a national evaluation of cancer services for teenagers and young adults in England. Following challenges with recruitment, our aim was to understand more fully healthcare professionals’ perspectives of the challenges of recruiting young people to a low-risk observational study, and to provide guidance for future recruitment processes.

Design

Qualitative.

Setting

National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England.

Methods

Semistructured telephone interviews with a convenience sample of 23 healthcare professionals. Participants included principal investigators/other staff recruiting into the BRIGHTLIGHT study. Data were analysed using framework analysis.

Results

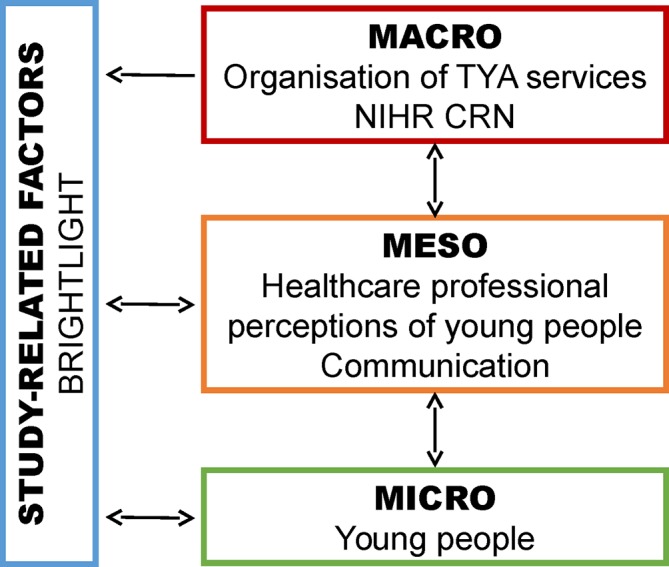

The emergent themes were linked to levels of research organisational management, described using the levels of social network analysis: micro-level (the individual; in this case the target population to be recruited—young people with cancer); meso-level (the organisation; refers to place of recruitment and people responsible for recruitment); and macro-level (the large-scale or global structure; refers to the wider research function of the NHS and associated policies). Study-related issues occurred across all three levels, which were influenced by the context of the study. At the meso-level, professionals’ perceptions of young people and communication between professionals generated age/cancer type silos, resulting in recruitment of either children or adults, but not both by the same team, and only in the cancer type the recruiting professional was aligned to. At the macro-level the main barrier was discordant configuration of a research service with a clinical service.

Conclusions

This study has identified significant barriers to recruitment mainly at the meso-level and macro-level, which are more challenging for research teams to influence. We suggest that interconnected whole-system changes are required to facilitate the success of interventions designed to improve recruitment. Interventions targeted at study design/management and the micro-level only may be less successful. We offer solutions to be considered by those involved at all levels of research for this population.

Keywords: recruitment, brightlight, teenager, young adult, cancer, research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study highlights that barriers to recruitment occur across multiple levels identified through in-depth interviews with healthcare professionals working in National Health Service (NHS) research across England.

Participants were recruited from the complete range of hospital environments where young people are cared for in the NHS, including oncology, haematology, adult, child and specialist teenage and young adult cancer units.

Barriers to recruitment for teenagers and young adults were examined, although the results may be transferable to other research in rare cancers.

This study explored the barriers to recruitment to a low-risk observational study, and there maybe wider issues in more complex studies of all designs.

Introduction

Challenges affecting recruitment to research studies in healthcare have been reported frequently in the literature1–4 and are often regarded as the most demanding phase of the research process. Various interventions have been used to improve recruitment, but few have been shown to be successful.5–7 What has received less attention is the identification and understanding of recruitment to research in populations often termed ‘hard to reach’; this includes people who are socially disadvantaged, viewed as vulnerable or low-frequency populations.8 One such group are teenagers and young adults (TYA) with cancer, who have been shown to have lower rates of recruitment to clinical trials than children and older adults,9 10 a factor that may contribute to worse clinical outcomes in this population.11 In a recent review of recruitment of young people with cancer to clinical trials, Fern et al10 identified five key issues to be addressed to optimise recruitment: awareness, availability, appropriateness, access and acceptability; this conceptual model was applied during the development and set-up of the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort study, a national evaluation of TYA cancer services in England.12

BRIGHTLIGHT cohort study in the context of recruitment to cancer clinical trials in England

In England research fulfilling specific criteria is eligible to be included in the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) portfolio of studies (http://www.nihr.ac.uk/research-and-impact/nihr-clinical-research-network-portfolio/, accessed 21 March 2017). Portfolio acceptance means the study is then eligible for support by healthcare professionals employed by the Clinical Research Network (CRN). This support includes study set-up and management. The CRN in England is divided into 15 networks supporting research in 30 clinical specialities (http://www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/how-we-are-managed/managing-centres/crn/our-structure.htm, accessed 21 March 2017), including cancer (the cancer network was reduced to 15 from 32 local networks in 2014). This network facilitates recruitment to research across the country by employing researchers (nurses, trial practitioners, data managers). The principal aim of the CRN is to increase accrual into clinical trials. However, it also supports other types of studies providing eligibility criteria for portfolio inclusion are fulfilled.

BRIGHTLIGHT is a cohort study involving young people with a primary cancer diagnosis made between the ages of 13 and 24 years. Data were collected from young people through a bespoke survey13 administered at 5–7, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months after diagnosis by an independent research company. Within the clinical setting healthcare professionals sought consent from young people to be contacted by the research company for data collection. Specialist cancer care for young people is provided by 13 principal treatment centres (PTC); however, approximately 50% of young people receive care outside of a PTC.14 In order to offer study participation to all young people, it was necessary to open the study to recruitment in as many hospitals in England as possible. Young people present with a spectrum of cancer types11 and are likely to attend various clinics within one hospital; thus, two challenges to recruitment were evident at the outset: (1) identifying young people who were potentially eligible for BRIGHTLIGHT; and (2) gaining their consent. The first challenge was overcome by using routinely collected National Health Service (NHS) data. The Cancer Waits data set records the details of all suspected cancer cases followed by the date of first treatment. While it is primarily designed to monitor government targets, used in real time (rather than after the end of year checks for accuracy) it was possible to identify young people within 3 months of diagnosis. This allowed the potential for recruitment of young people and data collection for the first survey within 5–7 months of diagnosis. The second challenge was overcome using the cancer registry which could distribute a list of patient names for each participating hospital to a designated member of the CRN based there, allowing a researcher working with the relevant cancer type to approach and recruit young people in that hospital (figure 1). The healthcare professional responsible for recruiting young people to BRIGHTLIGHT was hospital-dependent and ranged from a clinical trial assistant to the lead clinician for TYA.

Figure 1.

Summary of the process of recruiting to BRIGHTLIGHT. 1Recruiting until the day before the 25th birthday so this ensured we captured those diagnosed at 24.99 years but started treatment aged 25. 2This was a drop-down menu with several options: ‘Excluded (please specify), recruited, refused [+/-agree to contact details being retained], referred to another hospital, no longer treated at this hospital, no contact with the hospital this month, other (please specify)’. CWT, Cancer Wait Time data set; NWKIT, North West Knowledge Intelligence Team—the cancer registry responsible for TYA data; TYA, teenagers and young adults.

Prior feasibility work of this mechanism suggested we could recruit our target sample of 2012 young people in 18 months.15 However, our recruitment period needed to be extended by an additional 12 months with a reduced final sample of 1114 young people. Throughout the recruitment period, we implemented several changes to improve recruitment, none of which were successful.16

Studies in which healthcare professionals reflect on the research process have identified several factors perceived to impact on recruitment. These include bureaucratic delays in the NHS research and development approval process17 18; inadequate research infrastructure; perception of certain clinical trials being harder to recruit to; influence of the characteristics of those recruiting and those participating, which may mean some patients are not approached to participate19; competition for research participants; tension between clinical practice and clinical research workload; staff perception of patient benefit and burden; and the low status given to recruitment skills.1 These reasons are often taken and accepted at face value and are perpetuated across studies rather than being challenged and interrogated to look for structural-level and individual-level solutions to minimise their negative impact on recruitment.

Aims

To gather detailed understanding of the challenges to recruiting young people to BRIGHTLIGHT from the perspective of healthcare professionals involved in recruitment.

To provide guidance to optimise recruitment of young people to research in the future.

Methods

Study design

This was a qualitative study involving healthcare professionals involved in recruitment to the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort study as either principal investigators (PIs) or in other research roles.

Participants and setting

BRIGHTLIGHT was open to recruitment from September 2012 to April 2015 in 109 NHS hospitals in England. At the end of recruitment healthcare professionals (between 2 and 12 in each hospital) were requested to complete an End of Recruitment Questionnaire (EoRQ), with PIs asked to encourage at least one response per hospital.16 The EoRQ included the option to participate in a telephone interview to further explore the recruitment experience from the healthcare professionals’ perspective. Healthcare professionals who provided their contact details were sent an email by an experienced social science researcher (CK) independent from the BRIGHTLIGHT team, in which they were given a brief overview of the purpose and length of the interview (approximately 30 min). They were provided with a range of times/dates for the interview or could suggest alternative times/dates to enable flexibility around participation. Participation in the interview was taken as consent. Healthcare professionals could stop the interview at any time without specifying a reason. They were assured that their identity would remain confidential and not revealed to the BRIGHTLIGHT team.

Data collection

Data were collected through semistructured telephone interviews between July and August 2015, while recall of recruitment to BRIGHTLIGHT was still recent. The interview schedule was based on the EoRQ and established the role and involvement of the healthcare professionals in BRIGHTLIGHT, their research experience, preparedness for recruiting to BRIGHTLIGHT, and their approach to recruitment as well as the context for recruitment within their hospital, for example, involvement of research and clinical teams (see online supplementary file 1 for the results of the EoRQ). The interview also explored optimal recruitment mechanisms and particularly why this was not achieved, concluding with the interviewee’s overall reflection on the BRIGHTLIGHT study. At the end of the interview healthcare professionals were given the opportunity of adding any further comments. Additional probing ensured that responses could be further explored and clarified. For example, if specific reasons for not recruiting young people outside the eligibility criteria were reported, probes were used to understand the thought processes underpinning this decision and whether this was informed by communication with the BRIGHTLIGHT research team or was a local or individual interpretation of inclusion or exclusion criteria. With permission, all interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

bmjopen-2017-018291supp001.pdf (321KB, pdf)

Analysis

The interview data were analysed using framework analysis.20 21 This is a pragmatic approach that permits theme-based or case-based analysis and collaborative team analysis. It permits a structured and rigorous process for managing data, and provides transparency and an audit trail during analysis, and conclusions to be checked against the original data. The transcripts were anonymised (including all references to the hospitals involved) and divided between six members of the BRIGHTLIGHT team who each received three or four transcripts. They familiarised themselves with the transcripts and independently indexed and charted data summarising data per participant and theme based on a framework developed and piloted by two researchers (CK, RMT), both of whom had read all the transcripts. When complete, the charts were collated and collectively the research team met to discuss the charted data to identify key subthemes within each broad framework theme, enabling the data to be reduced into categories. The categories were refined through further discussion and checked against the original transcripts. Finally, another researcher (FG) reviewed the analysis to ensure interpretation remained true to the transcripts as a way of ensuring there was no bias (as the BRIGHTLIGHT team had been integral to the analysis).

Results

Forty-three healthcare professionals indicated they were willing to participate in an interview, of whom 36 provided contact details and 23 (64%) participated (table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | n | % |

| Professional background | ||

| Research nurse—adult | 15 | 66 |

| Research nurse—paediatric | 3 | 13 |

| Clinical nurse—TYA | 3 | 13 |

| Other | 2 | 8 |

| Type of hospital | ||

| TYA principal treatment centre | 5 | 22 |

| TYA designated hospital | 14 | 61 |

| Other cancer unit | 4 | 17 |

| Role in BRIGHTLIGHT | ||

| Principal investigator | 12 | 52 |

| Recruitment role | 11 | 48 |

TYA, teenage and young adult.

Emerging themes reflected the level within the English research network that the challenge arose; these are presented according to social network theory. A social network is defined as ‘any bounded set of connected social units’ and are characterised by boundaries between networks, being embedded in a larger social system and having links between members.22 Used here, theory-guided presentation of findings was relevant to make the most of the concept ‘network’ and the relationship between its constituent parts. The overarching themes are described using the levels of social network analysis23–25: micro (the individual), meso (the organisation) and macro (the large-scale or global network). This approach to the presentation of the findings has enabled subthemes to be described within the hierarchy of healthcare research in England:

Micro-level: refers to the target population to be recruited (eg, young people).

Meso-level: refers to the place where recruitment was occurring and the persons responsible for recruitment.

Macro-level: refers to the wider research/NHS structure and policies.

Study-related issues to the recruitment challenges occurred across the three levels and either influenced or were influenced by the context of the study (figure 2). These are presented first in our findings. We include relevant and occasionally long quotes, as well as probing questions used, where we thought it necessary to be expansive when emphasising a point.

Figure 2.

Challenges to recruitment by the level they occur. NIHR CRN, National Institute for Health Clinical Research Network; TYA, teenage and young adult.

Study-related factors

Before outlining the issues related to recruitment according to the three system levels, it is necessary to provide the context of healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the study. This refers to the design of a specific research project, the study coordinating team who are responsible for overseeing and managing the study including compliance with ethics, liaising with the sponsor and recruiting hospitals, and overall coordination of the study. In this paper, it refers to BRIGHTLIGHT and the BRIGHTLIGHT team primarily based at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Retrospectively healthcare professionals provided critiques and affirmative reflections on recruitment to BRIGHTLIGHT. One critique related to how healthcare professionals were informed of newly diagnosed young people through the monthly notification from the cancer registry. It was found that these did not identify young people in a timely manner despite the findings from the feasibility work.15 Consequently, young people were not recruited into the study because healthcare professionals became aware of them outside the recruitment window.

Then we were told [by the Network] that we didn’t need to do any screening and that we would be informed in time by those that had picked up patients from the cancer registry and we would be informed of those patients so we didn’t have to do any in-house screening and that didn’t work. By the time we got the list from the cancer registry…for the patients it was beyond the four months, therefore we missed the patients so that’s why we failed to recruit any patients and that was really frustrating.

There was a period when the registry stopped sending the notification files because of changes in Public Health England organisational infrastructure, and this was perceived by some healthcare professionals to have severely impacted on recruitment. However, the notification file was only suspended for 3 months, and by this time (April 2014) most young people were being identified and recruited independently of the notification list.

Overall healthcare professionals reported that they regarded BRIGHTLIGHT as a straightforward observational study of importance and relevance to the TYA patient population:

Well, TYA is quite underrepresented in research so it’s quite a good thing, the fact that it was observational, from our point of view it was quite easy to conduct, so we were more than happy to take part. I mean, we don’t do that many TYA people but it’s worth them being part of the research.

The PIs and others recruiting to the study were positive about the BRIGHTLIGHT team who oversaw and coordinated the study on a day-to-day basis, maintained engagement with each team throughout recruitment and were responsive to all their queries about the study:

I think there was very good, clear communication, we obviously kept up to date. I think the facilities on line, there was lots really, it was fairly well organised. I can’t say that anything, if I had any concerns, you know, [Senior Research Manager], they were very good, I’d only just pick up the phone or something. If I wasn’t sure about something in particular, then they’d put me on the right lines.

Micro-level

The micro-level refers to the individual, in this instance the target population to be recruited to a study. For BRIGHTLIGHT this related to issues specifically associated with the population being recruited. Healthcare professionals shared in interviews their reflections of young people that influenced recruitment.

We had previously identified from analysis of screening logs that young people were not being approached about the study.16 The interviews with healthcare professionals identified some reasons for this and generally felt they had approached all eligible patients presenting in their hospital. Healthcare professionals viewed BRIGHTLIGHT as being a less burdensome study in contrast to interventional clinical trials that may involve multiple hospital visits. With BRIGHTLIGHT, after gaining consent, young people’s participation was via surveys administered face-to-face, by telephone and online by an independent research company. They suggested that most young people wanted to have the opportunity to be involved in studies and use their experiences to contribute to improving services. For young people who did not want to participate, this was attributed to them not being bothered, time required to take part, and being negatively or positively influenced by peers in hospital:

I think they [TYA patients] couldn’t be bothered a little bit [with data collection]. Maybe not to feel well enough. The length, I think the conversations on the telephone were quite lengthy [completing a questionnaire]. You know yourself if you don’t want to talk to someone. I knew you were going to ring me today, but, you know, when someone is going to call you, you just think not right now. I think that was the problem. Then it used to filter through quite quickly to the unit. So, the young people would sit together and say, “Oh, they ring on this time,” or, “They keep ringing and it’s a lengthy procedure,” but since obviously we’re not recruiting anyone else, I haven’t heard any more from them, from what the patients’ opinions are.

What sort of things were they saying to each other?

Just that it was timely, lengthy chats. That they knew what the, with you know, if a certain number continued to ring repeatedly they’d choose to ignore it.

Meso-level

The meso-level refers to the organisation, in this instance the places where individuals were being recruited to the research. For BRIGHTLIGHT this related to the hospitals that opened to recruitment and researchers who were responsible for identifying, approaching and recruiting young people. There were two aspects related to healthcare professionals within these various organisations that impacted on recruitment: patient recruitment interactions and communication recruitment practices.

Patient recruitment interactions

Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of young people and their experience of recruiting this population to healthcare research varied. It was notable that aside from four TYA-specific healthcare professionals (three TYA clinical nurses and a medical consultant) the age specialism—adult or child—of the remaining healthcare professionals usually limited the age of patients they identified and approached for the study:

So, it’s kind of, for me, being an adult [Research Nurse] and the thought of dealing with, you know, these thirteen-year-old people with a cancer diagnosis was absolutely terrifying because I’d not worked with children of the-, I’ve only done a bit during my training and, you know, chose to work with adults because children are very terrifying and so the thought of then dealing with all of the issues that goes with a teenage cancer diagnosis, I actually found that very, very worrying. It was the recruitment process. They had talked to them. How do I consent them? It was then booking myself and the other research nurse onto paediatric GCP because we didn’t even understand the difference between assent and consent and it was how difficult was that going to be? Thankfully, everybody that we came across, within the Trust [hospital], who did enter the study, were actually within the adult age group. So, it wasn’t the issue that I first thought it was going to be, but it potentially could have been, you know, if we’d had people [paediatric TYA patients] who were remaining within the Trust [hospital].

In some sites, it appeared that an age-specific group of TYA patients either child or adult were never given the opportunity to participate in BRIGHTLIGHT with consequences for the overall study recruitment figures. It was also noted in eight transcripts that healthcare professionals who worked with adults referred to the TYA population as children, despite most of this population coming under adult care in other clinical settings. The ‘TYA’ label therefore seemed to impede recruitment. Additionally, screening and approaching patients were perceived to be a one-off opportunity, and if the young person was missed for example, not in the clinical area when the healthcare professional went to see them, then another attempt to inform them about the study and recruit may not have occurred.

In addition to age, some healthcare professionals also described an additional barrier of a desire to protect young people. Young people were perceived to need some form of protection due to the multiple ‘assumed’ vulnerabilities constructed around their age, diagnosis and treatment. This served to reinforce the view that young people were a challenge to engage within healthcare and therefore in research too. Despite their experience and knowledge of cancer, healthcare professionals emphasised the ‘cancer identity’ as a continual rather than periodic state of vulnerability as a reason not to approach some young people about BRIGHTLIGHT during the 4-month recruitment window from diagnosis. The perception of young people being too ill to approach about BRIGHTLIGHT did not necessarily apply to other research studies, such as drug trials requiring the processing of more complex information:

I mean, nobody’s [clinical staff] verbalised any concerns about the study, but obviously people didn’t value the study enough. I know, I recruit to randomized controlled trials and tox[icity] studies and I don’t have the same issues I’ve had with BRIGHTLIGHT.

Healthcare professionals’ interviews revealed a gap between the principle of conducting an observational study perceived to be straightforward and with broad inclusion criteria and the practice of identifying and recruiting the relevant population. Healthcare professionals who had experience in approaching young people to research reported positively and recruited well. However, some perceived it to be difficult particularly among ‘adult’ healthcare professionals, who rarely had contact with adolescent or young adult patients due to a low prevalence of cancer in this age group in their area of clinical expertise:

… as somebody who is an adult nurse. The patient I had was obviously about 24, so it was fine, it wouldn’t have bothered me, but thinking about a fourteen or a fifteen-year-old, that probably would have been a little bit more difficult.

Based on the responses of some healthcare professionals, it appeared, at times, those identifying and recruiting patients interpreted the inclusion/exclusion criteria beyond what was stipulated in the protocol; for example, there was no exclusion of patients receiving palliative care (exclude if not anticipated as being alive 5–7 months after diagnosis), but healthcare professionals reported assuming that if a patient was unlikely to be alive to complete all waves of data collection via questionnaire (3 years of participation), they were not eligible for the study. It is unlikely such interpretations would be made in clinical trials.

Communications and recruitment practices

Issues were identified relating to communication within hospitals. During study set-up the Site Readiness Questionnaire obtained information on how BRIGHTLIGHT would be implemented locally and no significant challenges were identified.16 Healthcare professionals reported mechanisms they had identified to link to multidisciplinary team (MDT) coordinators and clinical teams to identify young people. However, in practice this proved to be more complicated than anticipated. The interviews revealed disparity between the way communication mechanisms were perceived to work within the clinical area and their reality. While some healthcare professionals reported a link between child/adult cancer services, many had not used this link so recruited solely to the ‘age-silo’—child or adult—that they worked in rather than allow flexibility to accommodate the TYA (13–24 years old) research age range. Furthermore, in some hospitals recruitment was hindered by ‘cancer-type silos’ in addition to ‘age-silos’. Where BRIGHTLIGHT recruitment was designated to a healthcare professional working within a specific cancer type, recruitment was inhibited either due to the increased work burden or not recruiting patients with cancers outside their cancer type. This was the first realisation of BRIGHTLIGHT that mechanisms professionals had proposed to overcome the age and/or cancer silos were not a reality so some healthcare professionals stuck rigidly to their professional clinical boundaries rather than allow flexibility to accommodate the TYA (13–24 years old) research age range. This affected recruitment of the TYA population, which is cross-cutting age and cancer type:

So, is there anybody at your site recruiting the, I guess, 17 to 24 year olds?

No, there isn’t, or hasn’t been, sorry.

So, none of those would’ve been identified at your Trust [hospital]?

Well, you see, they have, some of ours don’t transition until they’re about eighteen, nineteen, but nothing, no none of the older ones. Which is such a shame, because I’m sure, you know, there was so many of the, you know, testicular cancers and that, that in younger adults, cancers should really have, but that was, kind of, outside of my remit.

The second communication issue related to staff turnover. Healthcare professionals who began recruitment to BRIGHTLIGHT did not always remain throughout the recruitment period. Prior to opening, hospitals needed to attend a site initiation visit or confirm they had watched the site initiation CD-ROM. After opening to recruitment there were no requests for additional site initiation visits nor were any requests received for the site initiation CD-ROM; when the BRIGHTLIGHT office was sent updated delegation logs, the assumption was that the new researcher assigned to recruit to BRIGHTLIGHT had also viewed the CD-ROM. However, healthcare professionals assigned to recruit to BRIGHTLIGHT after it had opened reported not knowing about the CD-ROM and relied on internal handover, which may have been a face-to-face meeting or reading the study site file. The communication pattern during transition of new staff also highlighted misunderstandings of the role of PI for those who had taken on the role, especially the responsibility they now had for ensuring successful recruitment.

Finally, recruitment was disadvantaged because there was no mechanism established either by BRIGHTLIGHT, the CRN or those recruiting at different hospitals to track whether patients were approached as their care moved between hospitals. For example, healthcare professionals especially from non-specialist hospitals reported that if young people were transferred soon after diagnosis to a specialist TYA unit, they hoped or assumed recruitment would occur in the specialist unit, but there was no established local mechanism to alert the receiving team of the eligibility of a young person or to check if they had been approached for the study or indeed recruited. Recognition of study accrual by the CRN is based on the organisation that recruits the patient so there was no incentive for healthcare professionals to contact referral hospitals to ensure the young person had been approached:

There were some that we did miss for various reasons. One of the main reasons, I think, that we missed some people is if they were transferred to another hospital for treatment. So, by the time I realised, or by the time the time was appropriate to speak to them, they had been referred to another hospital. So, that was the biggest reason.

Macro-level

The macro-level refers to the large-scale or global network, in this instance the way the NHS culture and configuration of services impacts on recruitment; for BRIGHTLIGHT it also related to the function of the CRN.

Clinical cancer services were based on a traditional two-population model (child/adult) until the introduction of the ‘Improving Outcomes Guidance’ in 2005,26 when there was the more formal acknowledgement of a third population: TYA (although some hospitals had introduced this model earlier). Since this time, it became evident that although TYA cancer care was recognised by commissioners for clinical services, this has not been replicated within the CRN, so research teams were still either focused on children or adults. Furthermore, adult research teams were assigned to a specific cancer type, rarely cross-cutting, so they would not capture the diverse cancer types young people present with (a factor making this population so unique10). It became evident within the interviews that creating a model of care that encompasses the three populations requires both a TYA-specific clinical team and a TYA-specific research team:

So most of our research department, and most of NHS research, is set up in terms of oncology, people with breast cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer and so forth. So it’s, kind of, tumour site specific and the whole cancer service is based around being some specialist, you know, specific research department. You’ve got nurses who work on neurology studies, or breast studies, or lung studies and it was a completely different mind shift when you start looking at age rather than tumour site specific.

The culture within cancer services in the NHS emerged as a barrier to recruitment. Recruitment to research and even screening was presented as being a role for the research team, and where there was no research support, recruitment suffered:

Then you’re in a situation where, okay, how do we recruit these patients? Because they’re in so many clinics. You can’t have one researcher running around all the clinics to recruit them, even though they are not so common. We don’t have TYA researchers, so we don’t have a TYA research department, so they’ve got research assistants doing neurology and breast and so forth and none doing TYA. Trying to ask these assistants to get involved was extremely difficult and eventually we failed…the recruitment was reliant on TYA nurses and doctors to do that. I tell you, as doctors, we can’t go to everything because you’ve got your own clinic and your own work to manage. So, although you concentrate on those patients, which are a small proportion that come to your clinic, you cannot completely cover different clinics. Again, it has been extremely difficult to get other consultants to think, “I will keep that in mind.” We tried to recruit those patients because, again, we’ve got 30 consultants and how many of them do you chase around?

Furthermore, there was a culture of viewing research according to a hierarchy in terms of clinical trial versus observational studies, with the latter having a lower priority for receiving attention. It was often deemed inappropriate to approach young people to participate in a low risk observation study as staff viewed this as burdensome and of little direct or immediate benefit to young people, although there may be less hesitancy approaching the same group of young people about participating in a clinical trial.

Finally, the CRN supports research in patients from cradle to grave, yet as noted previously the current subdivision of child–adult care created ‘age-silos’. It became evident that some hospitals had been pressurised to open BRIGHTLIGHT as TYA were a priority group for the National Cancer Research Institute. However, appropriate resources were not allocated to facilitate this. Even in specialist TYA units, where there were well-established clinical teams and large numbers of patients accessing the service, no resource was allocated to research this population by the local CRN. It was apparent that, although funding and resources should have been available to support recruitment to BRIGHTLIGHT, this did not play out in practice with resources being allocated elsewhere:

Yes. I suppose the challenge for me was that although we’re a big centre, we have very limited staff so I am the TYA nurse body for that. I don’t have a CNS. I don’t have a research nurse. So, it’s me and a TYA support worker. So, those two roles for 30 to 50 patients a year designated for the teenagers and young adults. That was my big challenge. It was just me. Yes. Although our research nurses did turn up…they were strapped…so pharma came first, I’m afraid.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand the challenges encountered by healthcare professionals responsible for the recruitment of young people to a national, low-risk, observational study. Many of the recruitment issues have been reported previously, such as bureaucratic delays,18 influence of professional attitudes of those recruiting and participant demographics,19 or notions of benefit or burden to participants.1 However, to our knowledge, this is the first time these issues have been discussed in relation to the level of study management and the social networks in which they occurred; this is important as interventions designed to improve recruitment need to be appropriately targeted and mindful of the context.

As with other studies,7 we implemented interventions to improve recruitment targeted predominantly on the study management and population (micro-level), none of which had a clearly demonstrable impact on recruitment.16 This study has identified that the significant barriers to recruitment tended to be at the meso-level and macro-level, where we had limited or no influence. Without holistic and interconnected changes, it is unlikely that interventions to improve recruitment solely targeted at study design/management and micro-levels will be successful. This holistic approach to recruitment requires the recognition that all levels are interconnected and need to work together to ensure equilibrium between micro-level, meso-level and macro-level.

We have found that within the context of this study, an ongoing face-to-face monitoring procedure would be beneficial, similar to those used in commercial clinical trials, with a clear purpose to check the running and progress of the study at each site. This would have provided an opportunity to update staff new to the study and increase ‘buy-in’ from healthcare professionals at each site, as well as enable feedback about local recruitment issues (which may be shared across multiple sites). It would also have provided opportunities for the main study team to develop solutions and ensure these were implemented via follow-up communication, also aiding the meso-level.

The micro-level issues associated with recruitment to a study and young people deciding to participate or not were not the focus of this study. Reasons young people do and do not take part in research have been reported elsewhere.27 However, it is important that where a young person is eligible to participate in a study, they are provided with the relevant information to make this choice.12 16 The micro-level and meso-level interconnect when healthcare professionals approach young people in the TYA age range (13–24). Young people are perceived to be hard to recruit to research10 and healthcare professionals reported difficulties in approaching this group, which appear to be due to a lack of confidence or experience particularly those working with adults. The perceived vulnerability (clinical, physical, social, emotional, financial) of the patient, particularly those who are children (under 18 years of age), may act as a deterrent or lead to the reticence of healthcare professionals to approach them to participate in research. However, ‘vulnerability’ is a fluid rather than constant state, so while a patient may not be approached at one point in time they could be at another time point—later on the same day, week or postintervention, for example, chemotherapy.

A key responsibility of a research ethics committee is to address issues of benefit and risk for a study population and to consider these in relation to the proposed study.28 This ensures that populations that might be regarded as vulnerable, such as young people with cancer, may be safely included within research studies. If populations, who due to their age or other factors, are excluded because they are ‘vulnerable’, then it may impact on the generalisability of research results. There are increasing expectations of research funders that patients as stakeholders are involved in all stages of research. The influence of their insights on a study should be made explicit to recruiting staff so that they better understand the priorities and perceptions of the study population.28–30 This may assist in challenging and overcoming professional preconceptions which may otherwise adversely affect study conduct. There may be another issue worthy of further investigation in that healthcare professionals may exhibit unconscious bias when designing research and recruiting to studies. If clinical research leaders have a poor experience of TYA patients adhering to treatment plans, for example, turning up for appointments, taking medication and so on, a general perception may arise that this population will be less likely to engage with research, thus potentially hampering future research focused on the population.

Learning from and applying some of the operational processes of interventional clinical trials, such as monitoring visits, may, by providing a greater level of formal contact, enhance site performance. Significant time had been invested into identifying potential recruitment problems with the main BRIGHTLIGHT team developing mechanisms within the study design for sites to enact prior to and during recruitment, yet quantitative evidence from the screening logs and recruitment figures16 and the qualitative data reported here suggest that recruitment problems associated with the population (micro-level) remained. However, the most substantial barrier to recruitment was at the meso-level, with healthcare professionals constructing the TYA population as ‘hard to reach’ and difficult to recruit. Healthcare professionals perceived young people’s ‘illness’ as a barrier, there was a lack of communication between hospitals when patients were referred elsewhere, and in some hospitals only specific healthcare professionals could consent patients. Our attempts to use the expertise of youth support coordinators and social workers, who the BRIGHTLIGHT user group felt were best suited to recruiting to this type of study,12 were thwarted by hospital research departments only allowing doctors and nurses to obtain consent.

These issues appeared to be universal, rather than sporadically related to individual hospitals, type of hospital or type of professional who was recruiting. Importantly recruitment at PTCs who provided specialist care for young people was not any better than non-specialist TYA Trusts.16 A possible reason for this may be the difference in service configuration with clinical services based on the three-population model (child, TYA, adult), whereas the research services generally remain child–adult. This perpetuates the age/cancer type silo that emerged in the current study, which impacted on BRIGHTLIGHT and could also be an important contributing factor to the decline in recruitment of those aged 15–24 to clinical trials.31

We found that there was no communication between hospitals when young people were transferred for specialist care. It could be envisaged that this could also occur for cancer types where treatment is complex requiring patients to attend more than one hospital. It might be worth developing a way for shared accrual to recognise that one site may identify a participant, but as their care is transferred consent is taken at another hospital. This may encourage interhospital communication and cooperation as there would be a shared benefit (accrual) and it may lead to a great number of eligible patients being approached for research.

Several suggestions have been proposed previously for macro-level interventions, such as sanctions imposed on hospitals or PIs when recruitment targets are not met32 and financial remuneration based on criteria other than study accrual.1 In addition, greater parity between how healthcare professionals view observational studies, which are often regarded as the poor relation to clinical trials, needs to be realised.33–35 This could be supported at macro-level through driving a change in Good Clinical Practice (GCP) training to reflect study designs beyond clinical trials and include training on consenting young adults. In turn this would also increase parity between clinical and observational studies, the range of methods for data collection, and their value in contributing to improved patient outcomes.

The networks were primarily set up to recruit to clinical trials in which they have been successful.36 As 5-year survival rates for many cancers reach into 80% and 90%, and with an increasing focus on patient-reported outcome measures, researchers and subsequently the networks must respond to an increasing need for research studies that are more observational in nature. No hierarchy associated with study design should exist as ultimately the goal is to improve overall outcomes for patients with cancer whether this be survival or quality of life. Our previous work with young people showed approximately three-quarters rated survival and quality of life as equally important.37

This study had several limitations. The interviewees were self-selected, so their subjective views and experiences are not necessarily representative of all those recruiting in their hospitals. However, the congruence of recruitment experiences across hospitals suggests that these were not one-off or hospital-specific issues. While saturation was reached on the issues raised by those who participated, a larger sample would have given us greater certainty that we could identify all the key issues. We did not report the experiences of young people being recruited to BRIGHTLIGHT or the experiences/perspectives of directors and senior managers in the CRNs of recruiting to a low-risk, cross-cutting age/cancer-type study. Despite these limitations this study indicates what needs to occur at different levels of research engagement for recruitment of young people with cancer to research (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Recommendations to improve recruitment to research. 1Low-represented also include, but are not limited to, the elderly, black and minority ethnic groups, people with the host language as a second language. NIHR CRN, National Institute for Health Clinical Research Network; TYA, teenage and young adult.

At the end of recruitment to BRIGHTLIGHT, it was clear that not all those eligible between 13–24 years and diagnosed during the time the study was open were given the opportunity to decide to participate. The ‘Improving Outcomes Guidance’26 specified young people should have access to clinical trials, and PTCs’ coordination of care needs to include access to trials and research as a core component of the MDT: ‘adequate resource provided for research nurses, clinical trials coordinators and data managers’ (p124). If a clinical service is developed to serve the unique needs of this population,26 then it is necessary to provide a similar research service, especially as the inclusion in research is a central recommendation and this is a target currently not being achieved.16 31 The importance of providing a population-specific research workforce was recognised from the inception of the CRN. Paediatric research resource exists across most hospitals in England providing cancer care. As more young people are diagnosed with cancer than children in England, it is not unreasonable to aspire to a TYA-specific research team, a team of healthcare professionals trained to work with young people who have the unique skill of acknowledging young people’s vulnerability while being able to identify when it is appropriate to approach them about all the opportunities available to them with respect to their treatment and care. This has recently been recognised by the NIHR CRN, and their TYA cancer research strategy proposed a number of objectives to address the continued disparity in recruitment of young people to research38 to increase availability of studies for the TYA population:

To establish a governance framework between TYA PTCs and designated centres and ensure equitable distribution of study sites.

To establish a network-wide TYA research nurse/worker infrastructure.

To establish systems linking trial recruitment data to registration data to allow all forms of population-based research to be undertaken (including those that do not require consent).

Whether there are resources allocated to achieve these objectives is unclear at this stage, but there is for the first time a strategic plan to address many of the issues identified in our study.

The changes we propose are accompanied by resource implications on time, funding and staffing; however, we suggest these will be short-term costs, which will be nullified in the longer term with a legacy of an improved holistic interconnected multilevel system to aid recruitment. This will ultimately lead to stronger evidence on which to base practice and policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following for all their support with recruitment to BRIGHTLIGHT: the NCRI, especially Dr Eileen Loucaides and the Secretariat; Dr Matt Seymour, Dr Matt Cooper and Dr Karen Poole at the former NCRN; Maria Khan (North West Knowledge Intelligence Team); TYAC; Teenage Cancer Trust; CLIC Sargent; Ipsos MORI; Quality Health and the research teams at 109 NHS Trusts in England who opened BRIGHTLIGHT to recruitment. The following are the principal Investigators agreeing to be acknowledged for their contribution to BRIGHTLIGHT recruitment: Claire Hemmaway, Barking, Havering and Redbridge Hospitals NHS Trust; Anita Amadi, Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals NHS Trust; Keith Elliott, Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Leanne Smith, Blackpool, Fylde and Wyre Hospitals NHS Trust; Shirley Cocks, Bolton NHS Foundation Trust; Victoria Drew, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Elizabeth Pask, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Anne Littley, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Mark Bower, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Trust; Scott Marshall, City Hospitals Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust; Lorna Dewar, Colchester Hospital University NHS Trust; Nnenna Osuji, Croydon Health Services NHS Trust; David Allotey, Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Karen Jewers, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust; Asha Johny, Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Nicola Knightly, Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Robert Carr, Guy’s & St Thomas' Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Alison Milne, Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Claire Hall, Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust; James Bailey, Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust; Christine Garlick, Ipswich Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Alison Brown, Isle of Wight Healthcare NHS Trust; Carolyn Hatch, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Vivienne E Andrews, Medway NHS Foundation Trust; Sara Greig, Milton Keynes Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Jennifer Wimperis, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital NHS Trust; Suriya Kirkpatrick, North Bristol NHS Trust; Jonathan Nicoll, North Cumbria University Hospitals NHS Trust; Ivo Hennig, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust; Karen Sherbourne, Oxford Radcliffe Hospital NHS Trust; Clare Turner, Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust; Claire Palles-Clark, Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Trust; Christine Cox, Royal United Hospital Bath NHS Trust; Yeng Ang, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust; Jonathan Cullis, Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust; Daniel Yeomanson, Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust; Ruth Logan, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Deborah Turner, South Devon Healthcare NHS Trust; Dianne Plews, South Tees Hospitals NHS Trust; Juliah Jonasi, Southend University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Ruth Pettengell, St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust; Kamal Khoobarry, Surrey & Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust; Angela Watts, The Dudley Group of Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Louise Soanes, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust; Claudette Jones, The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust; Michael Jenkinson, The Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery NHS Trust; Nicky Pettitt, University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust; Vijay Agarwal, University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust; Beth Harrison, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust; Fiona Miall, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust; Gail Wiley, University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Trust; Lynda Wagstaff, Walsall Hospitals NHS Trust; Fiona Smith, West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust; Sarah Janes, Western Sussex NHS Trust; Serena Hillman, Weston Area Health NHS Trust; and Christopher Zaborowski, Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Footnotes

Contributors: RMT, LAF, FG and JW were involved in developing the protocol. CK coordinated the running of the study and was responsible for data acquisition. CK, LAF, AM, SL, NN, FG and RMT contributed to the analysis. CK, RMT, AM and FG drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-1209-10013). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The BRIGHTLIGHT Team acknowledges the support of the NIHR, through the Cancer Research Network.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Study was approved by the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group and London Bloomsbury NHS Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data to share.

Author note: BRIGHTLIGHT Executive team also includes Dr Julie Barber, Dr Richard Feltbower, Louise Hooker, Martin Lerner, Professor Steve Morris, Dr Tony Moran, Hannah Millington, Dr Catherine O’Hara, Susie Pearce, Professor Rosalind Raine, Dr Dan Stark.

References

- 1.Adams M, Caffrey L, McKevitt C. Barriers and opportunities for enhancing patient recruitment and retention in clinical research: findings from an interview study in an NHS academic health science centre. Health Res Policy Syst 2015;13:8 10.1186/1478-4505-13-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. . Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer 2008;112:228–42. 10.1002/cncr.23157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay AE, Rae C, Fraser GA, et al. . Accrual of adolescents and young adults with cancer to clinical trials. Curr Oncol 2016;23:81–5. 10.3747/co.23.2925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald AM, Knight RC, Campbell MK, et al. . What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials 2006;7:9 10.1186/1745-6215-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower P, Brueton V, Gamble C, et al. . Interventions to improve recruitment and retention in clinical trials: a survey and workshop to assess current practice and future priorities. Trials 2014;15:399 10.1186/1745-6215-15-399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell MK, Snowdon C, Francis D, et al. . Recruitment to randomised trials: strategies for trial enrollment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:105 10.3310/hta11480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treweek S, Mitchell E, Pitkethly M, et al. . Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:MR000013 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. . Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:42 10.1186/1471-2288-14-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fern L, Davies S, Eden T, et al. . Rates of inclusion of teenagers and young adults in England into National Cancer Research Network clinical trials: report from the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Teenage and Young Adult Clinical Studies Development Group. Br J Cancer 2008;99:1967–74. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fern LA, Lewandowski JA, Coxon KM, et al. . Available, accessible, aware, appropriate, and acceptable: a strategy to improve participation of teenagers and young adults in cancer trials. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:e341–e350. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birch JM, Pang D, Alston RD, et al. . Survival from cancer in teenagers and young adults in England, 1979-2003. Br J Cancer 2008;99:830–5. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor RM, Solanki A, Aslam N, et al. . A participatory study of teenagers and young adults views on access and participation in cancer research. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016;20:156–64. 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor RM, Fern LA, Solanki A, et al. . Development and validation of the BRIGHTLIGHT Survey, a patient-reported experience measure for young people with cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:107 10.1186/s12955-015-0312-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Hara C, Khan M, McCabe M, et al. . Notifications of teenagers and young adults with cancer to a principal treatment centre 2009-2010. National Cancer Intelligence Network 2013. http://www.ncin.org.uk/view?rid=2124 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearce S, Gibson F, Fern L, et al. . The ’Essence of Care' for teenagers and young adults with cancer: a national longitudinal study to assess the benefits of specialist care. Phase 1 feasibility and scoping study. London: Teenage Cancer Trust, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor RM, Fern LA, O‘Hara C‘G F, et al. . Critical reflections on strategies implemented to optimise recruitment of young people with cancer to the BRIGHTLIGHT Cohort Study.Unpublished 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snooks H, Hutchings H, Seagrove A, et al. . Bureaucracy stifles medical research in Britain: a tale of three trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:122 10.1186/1471-2288-12-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treweek S, Wilkie E, Craigie AM, et al. . Meeting the challenges of recruitment to multicentre, community-based, lifestyle-change trials: a case study of the BeWEL trial. Trials 2013;14:436 10.1186/1745-6215-14-436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newington L, Metcalfe A. Factors influencing recruitment to research: qualitative study of the experiences and perceptions of research teams. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:10 10.1186/1471-2288-14-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London, UK: Sage Publications Inc, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. : Bryman A, Burgess RG, London, UK: Routledge, 1994:173–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Streeter CL, Gillespie DF. Social Network Analysis. J Soc Serv Res 1993;16:201–22. 10.1300/J079v16n01_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faust K, Wasserman S. Social network analysis: methods and applications (structural analysis in the social sciences). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadushin C. Understanding social networks: Theories, concepts and findings. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman M, Albert-Laszlo B, Watts DJ. The structure and synamics of networks (Princeton Studies in Complexity). Princeton University Press: Oxford, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidance on cancer services: improving outcomes in children and young people with cancer. London: NICE, 2005. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg7/resources/improving-outcomes-in-children-and-young-people-with-cancer-update-773378893 (accessed 09 Sep 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearce S, Brownsdon A, Fern L, et al. . The perceptions of teenagers, young adults and professionals in the participation of bone cancer clinical trials. Eur J Cancer Care 2016:n/a 10.1111/ecc.12476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bracken-Roche D, Bell E, Macdonald ME, et al. . The concept of ‘vulnerability’ in research ethics: an in-depth analysis of policies and guidelines. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:8 10.1186/s12961-016-0164-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Children and clinical research: ethical issues. London: Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright K. Are children vulnerable in research? Asian Bioeth Rev 2015;7:201–13. 10.1353/asb.2015.0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fern L, Alexander S, Whelan J. Ten year trends of participation of teenagers and young adults (TYA) in selected NIHR National Cancer Research Network trials. NCRI Cancer Conference, 2016. http://abstracts.ncri.org.uk/abstract/ten-year-trends-of-participation-of-teenagers-and-young-adults-tya-in-selected-nihr-national-cancer-research-network-trials/ [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dal-Ré R, Moher D, Gluud C, et al. . Disclosure of investigators’ recruitment performance in multicenter clinical trials: a further step for research transparency. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001149 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barton S. Which clinical studies provide the best evidence? The best RCT still trumps the best observational study. BMJ 2000;321:255–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Concato J. Observational versus experimental studies: what’s the evidence for a hierarchy? NeuroRx 2004;1:341–7. 10.1602/neurorx.1.3.341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Observational studies versus randomized controlled trials: avenues to causal inference in nephrology. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2012;19:11–18. 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.KPMG. 2016. NIHR Clinical Research Network: Impact and Value Assessment FINAL REPORT: KPMG; https://www.nihr.ac.uk/life-sciences-industry/documents/NIHR%20CRN%20Impact%20and%20Value%20FINAL%20REPORT_vSTC_160908_FOR%20EXTERNAL%20USE.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fern L, Ashton J, Brooman K, et al. . Which research priorities are defined by young people with cancer- second consultation by the National Cancer Research Institute’s Teenage and Young Adult Core Consumer Group. National Cancer Research Institute Cancer Conference; 2010. http://abstracts.ncri.org.uk/abstract/which-research-priorities-are-defined-by-young-people-with-cancer-second-consultation-by-the-national-cancer-research-institute%C2%92s-teenage-and-young-adult-core-consumer-group-3/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burke A, Anwar S, Gower J, et al. . NIHR Clinical research network teenage and young adults (tya) cancer strategy. Leeds: NIHR CRN, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018291supp001.pdf (321KB, pdf)