Abstract

Objectives

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) is the most common inherited disorder of the peripheral nervous system, yet no studies have compared the mortality in patients with CMT with that of the general population, and prevalence estimates vary considerably. We performed a nationwide register-based study to investigate the prevalence, incidence and mortality of CMT in Denmark.

Design

We used the Danish National Patient Registry to select all records with primary diagnostic codes for CMT between 1977 and 2012 given at a neurological, neurophysiological, paediatric or clinical genetic clinic. The prevalence was estimated by 31 December 2012, and the incidence rate was calculated based on data from 1988 to 2012. We calculated a standardised mortality ratio (SMR) and an absolute excess mortality rate (AER) stratified according to age categories and disease duration.

Results

A total of 1534 patients (652 women) were identified. The prevalence proportion was 22.5 per 100 000 (95% CI 21.2 to 23.7) and the incidence rate was 0.98 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.04) per 100 000 person-years. The SMR was 1.36 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.53), and the AER was 4.87 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 2.77 to 6.96). We found a significantly higher SMR in cases below 50 years of age, and in cases with disease duration of more than 10 years.

Conclusions

We found a reduced life expectancy among patients diagnosed with CMT. To our knowledge, this is the first study of CMT to use nationwide register-based data, and the first to report an SMR and an AER.

Keywords: neuromuscular disease, epidemiology, neurogenetics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first nationwide register-based study of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT).

Data have been collected from the Danish National Patients Registry (DNPR); a high-quality national registry with prospective data collection, thereby minimising selection bias.

The study is based on a large cohort of patients (n=1534) diagnosed with CMT between 1977 and 2012.

The DNPR only includes hospital contacts; therefore, patients with CMT not admitted and diagnosed at a hospital department are not included, which might be the case for many mildly affected patients,

Misdiagnosed cases due to atypical CMT symptoms and signs are missing in this study, as we only included patients who are registered with a CMT diagnosis in the DNPR.

Introduction

The Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) is both clinically and genetically heterogeneous. The typical signs are slowly progressive muscle weakness of the extremities, deformities of the feet and hands, loss of tendon reflexes and mild to severe sensory loss. However, symptoms and severity as well as age at onset can vary considerably, even within the same family.1 This heterogeneity makes CMT a great challenge in diagnostics as well as epidemiology. CMT is known as one of the most common hereditary neurological disorders,2 but prevalence estimates in the literature vary greatly, ranging from 9.7 per 100 000 in Serbia3 to 82.3 per 100 000 in Norway.4 In recent years, knowledge of CMT has increased, as more and more CMT-associated genes have been discovered owing to the development of massive parallel sequencing technologies. Today, mutations in more than 80 CMT and related neuropathy genes have been identified.5 In spite of this increase in research, epidemiological knowledge about CMT is still scarce. The lifespan of patients with CMT is generally assumed to be normal,2 6 yet to our knowledge, the mortality of patients with CMT has never been compared with the mortality in the general population. Recently, Barreto et al reviewed the epidemiological literature on CMT and reported great variation in methods as well as quality, and stressed the need for further epidemiological research.7

The aim of this study was to perform a nationwide register-based study of the prevalence, incidence and mortality of CMT in Denmark, using data from the Danish National Patients Registry (DNPR), which is considered one of the finest national health registers in the world.8 In a previous study, we found a high validity of the CMT diagnoses in the DNPR, thus supporting the use of the DNPR in epidemiological research on CMT.9

Methods

Setting and data sources

Denmark is a country with 5.6 million inhabitants. All citizens have free access to tax-funded healthcare from the Danish National Health Service. Since 1968, all citizens have been registered in the Danish Civil Registration System, given a unique 10-digit identification number (CPR number). The Danish Civil Registration System contains information on gender, date of birth and death, and the CPR number enables unambiguous linkage between databases and national registries.10 The DNPR was established in 1977, and contains information on all non-psychiatric hospital admissions. Outpatient contacts were added in 1995. Data in the DNPR are recorded prospectively, and include information on discharge diagnosis, diagnosis type (primary, secondary), supplementary diagnoses, hospital department, and admission and discharge dates. Diagnoses are registered according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), from 1977 to 1993 according to the 8th revision (ICD-8), and hereafter according to the 10th revision (ICD-10).8 In a previous study, the positive predictive value (PPV) of the CMT diagnoses in the DNPR was reported as 88.5%.9

Study population

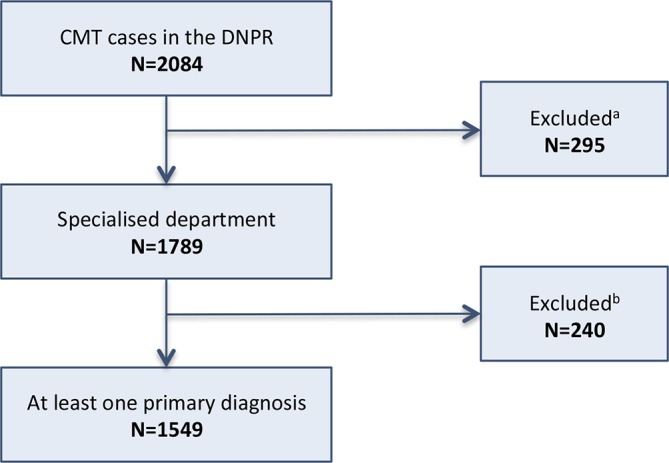

The study was based on data from 1977 to 2012. Diagnostic codes consistent with CMT (ICD-10 DG60.0 Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy and ICD-8 33009 Atrophia mm. neuropathica, Charcot-Marie-Tooth) were identified. Data on all patients with at least one CMT diagnosis were retrieved from the DNPR. To ensure the highest quality of data, we excluded patients not diagnosed at departments of neurology, neurophysiology, clinical genetics or paediatrics, and patients who only had secondary CMT diagnoses. A similar approach was used in the validation study described above.9 A flow chart of the selection process is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study population selection. CMT case: diagnosed with ICD-8 33009 or ICD-10 DG60.0. Specialised department: at least one diagnosis (ICD-8 33009 or ICD-10 DG60.0) given at a neurological, neurophysiological, paediatric or clinical genetic department. Excludeda: cases not diagnosed at a specialised department. Excludedb: cases only registered with a secondary CMT diagnosis. CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; DNPR, Danish National Patients Registry.

Statistical analysis

The CMT prevalence was calculated as the number of patients with CMT alive by the end of 2012 compared with the total population size. Prevalence proportions with 95% confidence limits for each gender and in each of four age categories were derived in a similar way. Information on the total population size by 31 December 2012 categorised by age and gender was obtained from the Statistics Denmark.11

An incidence rate with a 95% CI was computed for the period 1988–2012 and also for 5-year calendar periods starting in 1988. CMT diagnoses could not be identified prior to the establishment of DNPR in 1977. Therefore, early in the study period, some patients who had their first CMT diagnosis registered in DNPR may have been diagnosed with CMT before 1977. The first diagnosis in DNPR would then erroneously be identified as the patient’s first diagnosis of CMT, causing a spurious increase in the incidence. To minimise this problem, patients with a first CMT diagnosis registered in DNPR in the period 1977–1987 and the corresponding person-years at risk were excluded from the calculation of incidence rates. CMT incidence rates were computed as the number of new CMT diagnoses in a calendar period divided by the person-years at risk in the same period. Person-years at risk were estimated as the sum of midyear population sizes for the relevant calendar years using midyear population sizes obtained from Statistics Denmark.11

A PPV-adjusted overall prevalence proportion and overall incidence rate were also obtained. The corresponding CIs accounted for the statistical uncertainty in the PPV estimate.

The mortality in the CMT cohort was compared with that of the general Danish population in the same period. Each patient with CMT was followed from date of first CMT diagnosis in DNPR until 31 December 2012, date of death or date of emigration. Information on death and emigration was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System by record linkage using the patient’s CPR number. The observed number of deaths was compared with the expected number of deaths derived from gender, age and period-specific mortality rates for the general population.12 13 The population rates were obtained from gender-specific life tables based on 5-year calendar periods and 1 year age category published by Statistics Denmark.11 The observed and expected number of deaths was compared by computing a standardised mortality ratio (SMR) and an absolute excess rate (AER) with 95% CIs. The SMR is the ratio of observed number of death to expected number of death and is therefore the relative excess rate plus 1. The AER is the difference between the observed number and the expected number of deaths divided by the person-years at risk. SMR and AER were computed for each gender and four age categories (0–29, 30–49, 50–69 and 70–99 years) and two categories of time since first diagnosis (duration) (0–9 and >10 years). Stata V.1314 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

A total of 2065 patients were registered with a CMT diagnosis in the DNPR between 1977 and 2012, using the selection criteria as described above. In the final study population, 1534 patients were included (882 men and 652 women). The selection process is illustrated in figure 1, and the distribution of patients according to selection criteria is shown in table 1. The average age at first diagnosis was 42.5 years (43.2 years in men and 41.5 years in women). The range of age at first diagnosis was 0–91 years, and the average age at death was 70 years.

Table 1.

Distribution of selection criteria among all patients diagnosed with CMT in the DNPR from 1977 to 2012

| Diagnosis type | Specialised department | Not specialised department | All | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Only primary diagnosis | 1190 | (67.1) | 150 | (51.5) | 1340 | (64.9) |

| Primary and secondary diagnoses | 344 | (19.4) | 37 | (12.7) | 381 | (18.5) |

| Only secondary diagnosis | 240 | (13.5) | 104 | (35.7) | 344 | (16.7) |

| Total | 1774 | (100) | 291 | (100) | 2065 | (100) |

Specialised department: at least one diagnosis (ICD-8 33009 or ICD-10 DG60.0) given at a neurological, neurophysiological, paediatric or clinical genetic department.

CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; DNPR, Danish National Patients Registry; ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

A total of 1258 patients with a CMT diagnosis were alive by 31 December 2012 among 5 602 628 residents in Denmark, corresponding to a prevalence proportion of 22.5 per 100 000 (95% CI 21.2 to 23.7). The distribution of prevalence according to age and gender is shown in table 2. The highest prevalence (45.2 per 100 000) was found among men in the 70+ years age group. The PPV-adjusted prevalence was 19.9 per 100 000 (95% CI 18.2 to 21.7) when using a PPV of 88.5%.9

Table 2.

CMT prevalence per 100 000 by 31 December 2012 stratified by age and gender

| Age category (years) | Male | 95% CI | Female | 95% CI | Total | 95% CI |

| 0–29 | 15.4 | 13.0 to 17.8 | 12.5 | 10.3 to 14.7 | 14.0 | 12.3 to 15.6 |

| 30–49 | 20.6 | 17.4 to 23.8 | 20.2 | 17.0 to 23.4 | 20.4 | 18.1 to 22.7 |

| 50–69 | 36.1 | 31.7 to 40.5 | 28.1 | 24.2 to 32.0 | 32.1 | 29.1 to 35.0 |

| 70+ | 45.2 | 37.3 to 53.1 | 23.0 | 18.1 to 27.9 | 32.6 | 28.2 to 37.0 |

| Total | 25.1 | 23.2 to 26.9 | 19.9 | 18.2 to 21.5 | 22.5 | 21.2 to 23.7 |

CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

Our results showed the lowest prevalence in the youngest age group and the highest prevalence in the older age groups. There was a statistically significant higher prevalence in men than women (P<0.001) (table 2).

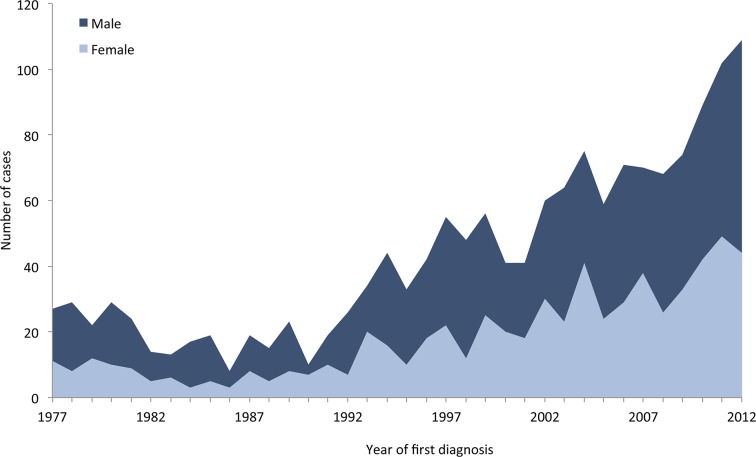

As described above, the incidence rate was calculated for the period 1988–2012: a total of 1313 patients received their first CMT diagnosis during this period, in which the general population accumulated a total of 133 445 087 person-years. The overall incidence rate was 0.98 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 0.93 to 1.04), 1.12 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 1.05 to 1.21) for men and 0.85 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 0.78 to 0.92) for women. The incidence rate in the period 1988–1992 was 0.36 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 0.29 to 0.44) and the incidence rate in the period 2008–2012 was 1.58 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 1.44 to 1.73), corresponding to an increase in the incidence by a factor of 4.4 during this 20-year period. The PPV-adjusted overall incidence rate was 0.87 per 100 000 person-years (95% CI 0.80 to 0.95). The distribution of new CMT diagnoses in the period 1977–2012 is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of first Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) diagnoses per year in the Danish National Patients Registry (DNPR) from 1977 to 2012 in men and women.

A total of 295 deaths were observed before 1 January 2013 for a total of 15 948 person-years. The expected number of deaths in the matched general population was 216.8. The overall SMR was 1.36 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.53), and the overall AER was 4.91 (95% CI 2.79 to 7.02) per 1000 person-years. Table 3 shows the SMR and the AER according to gender (only SMR), age category and disease duration (time from first diagnosis). The SMR decreased with age but increased with disease duration. The highest SMR was observed in men in the 0–29 years age group (6.01 (95% CI 3.00 to 12.01)). The AER increased with both age and disease duration.

Table 3.

SMR and an AER stratified according to age category and time since first diagnosis. SMR is also stratified according to gender

| Gender | Age category (years) | Duration category (years) | Total | ||||

| 0–29 | 30–49 | 50–69 | 70–99 | 0–9 | 10+ | ||

| Male | |||||||

| Observed | 8 | 12 | 63 | 113 | 104 | 92 | 196 |

| Expected | 1.33 | 6.18 | 40.35 | 96.74 | 89.13 | 55.48 | 144.6 |

| SMR | 6.01 | 1.94 | 1.56 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.66 | 1.36 |

| 95% CI | (3.00 to 12.01) | (1.10 to 3.43) | (1.22 to 2.00) | (0.97 to 1.40) | (0.96 to 1.41) | (1.35 to 2.03) | (1.18 to 1.56) |

| Female | |||||||

| Observed | 2 | 15 | 21 | 61 | 53 | 47 | 99 |

| Expected | 0.43 | 2.49 | 15.68 | 53.57 | 44.3 | 27.86 | 72.16 |

| SMR | 4.66 | 6.04 | 1.34 | 1.14 | 1.17 | 1.69 | 1.37 |

| 95% CI | (1.17 to 18.63) | (3.64 to 10.01) | (0.87 to 2.05) | (0.89 to 1.46) | (0.89 to 1.54) | (1.27 to 2.25) | (1.14 to 1.68) |

| Total | |||||||

| Observed | 10 | 27 | 84 | 174 | 156 | 139 | 295 |

| Expected | 1.76 | 8.66 | 56.03 | 150.31 | 134.43 | 83.34 | 216.76 |

| SMR | 5.68 | 3.12 | 1.50 | 1.16 | 1.17 | 1.67 | 1.36 |

| 95% CI | (3.06 to 10.55) | (2.14 to 4.55) | (1.21 to 1.86) | (1.00 to 1.34) | (1.00 to 1.37) | (1.41 to 1.97) | (1.21 to 1.53) |

| Risk time (years) | 3992.02 | 4667.34 | 4963.88 | 2325.02 | 10 524.5 | 5423.77 | 15 948.27 |

| AER/1000 years | 2.06 | 3.93 | 5.63 | 10.19 | 2.14 | 10.26 | 4.91 |

| 95% CI | (0.51 to 3.62) | (1.75 to 6.11) | (2.02 to 9.25) | (−0.93 to 21.31) | (−0.18 to 4.47) | (6.00 to 14.52) | (2.79 to 7.02) |

AER, absolute excess rate; SMR, standardised mortality ratio.

Discussion

In this nationwide study, we used national register data from the DNPR to identify 1534 patients diagnosed with CMT during a 35-year period. We report a 36% higher mortality among patients diagnosed with CMT as compared with the general population. We found a prevalence of 22.5 per 100 000 and a more than fourfold increase in the incidence from 1988 to 2012.

The DNPR is a high-quality health registry; selection bias is minimised due to the universal nature of the Danish healthcare system and the nationwide coverage and prospective data collection.8 We have previously reported a high validity of the CMT diagnoses, supporting the use of the DNPR in epidemiological research on CMT.9 However, the CMT population in our study is not complete, as the DNPR only covers patients with hospital contact since 1977. Patients with milder signs and symptoms, or patients to whom CMT is already a well-known part of their family history, might never be referred to a hospital department. Other patients with mild or atypical symptoms may have been misdiagnosed, for example, as having another neurological disorder, and an unknown number of individuals with CMT or latent CMT will have died before the diagnosis could be established. Patients diagnosed before 1977 who have not received a second diagnosis are missing from our study. Before 1995, the DNPR only included data from hospital admissions, therefore any CMT diagnosis given at an outpatient contact before 1995 is missing from our data. However, the healthcare system in Denmark has changed considerably during the study period; many hospital admissions from before 1995 would probably be performed as outpatient contacts today.

The selection of patients based on department and diagnosis type may also have excluded an unknown number of patients with CMT also. Although we only included specialised departments presumed to have considerably experience with diagnosing CMT, we cannot exclude incorrect CMT diagnosis in some cases. However, as mentioned earlier, in a previous study we found that the validity of the CMT diagnosis is high in the DNPR.9 The DNPR does not include a categorisation according to CMT subtype. We did not attempt to gather information from genetic or neurophysiological evaluations, and thus cannot present an estimate of the distribution of subtypes.

Based on the missing CMT cases in our data, as described above, the prevalence in our study is likely to be underestimated, and should be regarded as a minimum estimate. On the other hand, the PPV used to derive the PPV-adjusted prevalence and incidence might be underestimated, as we have previously reported trends for a higher PPV in cases diagnosed between ages 30 and 49 years, cases diagnosed after year 2000 and among women.9

The increase in incidence seen since the early 1990’s is most likely an effect of changes in the organisation of the Danish National Health Service and in the DNPR: in 1992 the first genetic analysis for CMT became available to clinicians, and since then the number of genes available for analysis, as well as the general awareness of hereditary disorders, has increased steadily. In 1994, the classification system changed from ICD-8 to ICD-10, and in 1995 outpatient data were added to the DNPR.8 The higher incidence early in the study period is most likely due to the inclusion of CMT cases diagnosed before the DNPR was established in 1977. To avoid false first diagnoses, we calculated the incidence rate from 1988, yet the incidence is still likely to be overestimated, as approximately half of the patients alive had not received a second diagnosis after 15 years of follow-up (data not shown).

Prevalence estimates in the literature vary greatly: in a recent review, Barreto et al assessed the quality and results of epidemiological studies of CMT worldwide. Prevalence estimates were found within a range from 9.7 to 82.3 per 100 000.3 4 Medical record review was used in data collection in the majority of the studies, although methodology otherwise varied considerably.7 To our knowledge, the present study is the first to use nationwide register-based data, which gives us the advantage of a large population, but limits the detail in information; unlike many other studies, we do not have data on CMT subtypes. Our prevalence result is similar to studies from Sweden (20.1/100 000)15 and the UK (18.1/100 000).16

The highest and most frequently cited prevalence estimates have been reported in two studies from Norway.2 4 In both Norwegian studies, meticulous effort was put into the search for undiagnosed relatives with CMT, which may be part of the explanation for the high prevalence estimates.4 7 In our study, we did not attempt to identify undiagnosed family members. As argued above, our CMT population is not complete, and our calculated prevalence is likely to be underestimated. We found a significantly higher prevalence of men diagnosed with CMT as compared with women. Similar findings have been reported by Mladenovic et al and Gudmundsson et al3 17; however, Braathen et al reported a higher prevalence in women4 and Morocutti et al found no difference in prevalence between the sexes.18

Results on incidence and prevalence of CMT in Denmark have previously been presented by Werdelin and Keiding.19 Their study included 126 cases with hereditary ataxias (defined as cerebellar ataxia, Friedreich’s ataxia, hereditary spastic paraplegia and CMT) from the Danish island of Zealand in the period 1961–1975. The study included 46 cases with CMT with an age between 10 and 50 years at first diagnosis. Werdelin and Keiding used probands to estimate incidence rates and found highest incidence at ages below 30 years. Prevalence was estimated from incidence and mortality information using methodology based on a stationary population assumption. This approach was clearly not appropriate for the present study and we therefore estimated the prevalence directly from the number of CMT cases alive by the end of 2012.

Apart from the study by Werdelin and Keiding, we have not been able to find other reports on the incidence of CMT.

Based on the limitations in our study population as discussed above, the mortality may have been overestimated if many of the assumed missing cases were mildly affected individuals (given that mortality is linked to the severity of CMT). Another aspect that may have influenced the mortality outcome was the use of age at first diagnosis as time of disease onset. Age at onset is extremely difficult to establish in a slowly progressive disorder such as CMT, and many patients are diagnosed long after onset of symptoms. However, since patients were identified at the date of first diagnosis in the DNPR, follow-up must start at this date to avoid survival bias.

Survival of patients with CMT was studied by comparing the mortality in the study population with the mortality in the general population. The excess mortality was described using both a multiplicative model (SMR) and an additive model (AER) for the mortality rate. The two descriptions complement each other and together provide a more complete picture of how the excess mortality depends on age and time since first diagnosis (ie, duration of disease). Overall, the excess mortality was modest, but statistically significant; we found 295 deaths where 217 were expected, giving an SMR of 1.36. This SMR is slightly smaller than the SMR describing the excess mortality seen for men relative to women in Denmark.20 We found similar trends with age and duration in excess mortality for men and women. Regarding the age dependence, we found that the AER increased with age, whereas the SMR, and therefore also the relative excess rate, decreased with increasing age. This pattern shows that the excess mortality rises with age, but not as fast as the mortality of the general population. The higher SMR values in the younger age categories probably reflect the low overall mortality in young people rather than a high excess mortality. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that the AER is quite small for the youngest age category. We also calculated separate SMR and AER values for two categories of duration of disease. Interestingly, we observed an increasing excess mortality both in absolute and relative terms. The decreasing SMR with age that would imply a lower relative excess mortality in the highest duration category was apparently counteracted by an increased mortality with time since diagnosis, suggesting that comorbidities or general frailty accumulates and leads to higher excess mortality.

Some CMT subtypes are known to be more severe than others, and could have a higher mortality than other subtypes.2 3 Especially X-linked CMT in men, and certain CMT2 and CMT4 subtypes have a more severe disease course, with very early onset and sometimes involving diaphragm paralysis.21 22 The latter may be associated with higher risk of pulmonary morbidity and early mortality as addressed by Abboud et al.23 Unfortunately, due to the limitation of our data, we were unable to investigate if certain CMT subtypes were associated with a higher mortality than others.

To our knowledge, no prior studies on CMT have reported SMR or AER estimates; hence our results cannot be directly compared with other studies. The issue of survival in CMT has been addressed in a study by Mladenovic et al, who reported a cumulative probability of a 15-year survival in a population of 161 patients with CMT. Unlike our study, Mladenovic et al used internal comparison; however, similar to our study, they found an unfavourable prognostic factor for younger age at onset.3 The study of Werdelin and Keiding presents survival curves corrected for delayed entry. However, they do not compare survival (or mortality) of patients with that of the general population and their results are therefore not directly comparable with our results.

Until now, it has been generally assumed that the lifespan of patients with CMT was unaffected.2 6 However, our study of a large group of patients diagnosed with CMT reveals a significant increase in mortality. This finding brings to light a new set of intriguing questions and areas for further research to what causes this increase in mortality. One important question in terms of intervention is whether the increased mortality is caused by an accumulation of comorbidities, or is explained by the CMT disease itself. Being a chronic progressive disorder, patients with CMT have needs for long-term and continuous medical and social support. Further understanding of the excess mortality in CMT could help target the research and public health resources to the areas of greatest effect.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SV and UBJ were responsible for the acquisition of data. SV was responsible for data management and initial drafting of the manuscript. MV was responsible for the statistical analysis and contributed to the data management and the initial drafting of the manuscript. SV, MV, HA, RC and UBJ contributed to the research idea, study design and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from Innovation Fund Denmark (UBJ), Aarhus University Hospital (UBJ) and Aarhus University (SV).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record number 1-16-02-18-12). Ethics committee review is not required for register data studies in Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available upon request by emailing vaeth@dadlnet.dk.

References

- 1. Harding AE, Thomas PK. The clinical features of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy types I and II. Brain 1980;103:259–80. 10.1093/brain/103.2.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Skre H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease. Clin Genet 1974;6:98–118. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mladenovic J, Milic Rasic V, Keckarevic Markovic M, et al. Epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in the population of Belgrade, Serbia. Neuroepidemiology 2011;36:177–82. 10.1159/000327029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braathen GJ, Sand JC, Lobato A, et al. Genetic epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth in the general population. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:39–48. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Timmerman V, Strickland AV, Züchner S, et al. Genetics of Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) Disease within the frame of the human genome project success. Genes 2014;5:13–32. 10.3390/genes5010013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lupski J, Garcia C, Parry G. Charcot-Marie-Tooth polyneuropathy syndroem: clinical, electrophysiological, and genetic aspects. Current Neurology Chicago: Mosby-Year Book; 1991:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barreto LC, Oliveira FS, Nunes PS, et al. Epidemiologic study of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 2016;46:157–65. 10.1159/000443706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vaeth S, Jensen UB, Christensen R, et al. Validation of diagnostic codes for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in the Danish National Patient Registry. Clin Epidemiol 2016;8:783–7. 10.2147/CLEP.S115565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Statistics Denmark. http://www.statistikbanken.dk/ (accessed 1 Jun 2016).

- 12. Buckley JD. Additive and multiplicative models for relative survival rates. Biometrics 1984;40:51–62. 10.2307/2530743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andersen PK, Vaeth M. Simple parametric and nonparametric models for excess and relative mortality. Biometrics 1989;45:523–35. 10.2307/2531494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. StataCorp. Stata: Release 13. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holmberg BH. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in Northern Sweden: an epidemiological and clinical study. Acta Neurol Scand 1993;87:416–22. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1993.tb04127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. MacMillan JC, Harper PS. The Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome: clinical aspects from a population study in South Wales, UK. Clin Genet 1994;45:128–34. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb04009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gudmundsson B, Olafsson E, Jakobsson F, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in Iceland: a study of a well-defined population. Neuroepidemiology 2010;34:13–17. 10.1159/000255461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morocutti C, Colazza GB, Soldati G, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in Molise, a central-southern region of Italy: an epidemiological study. Neuroepidemiology 2002;21:241–5. 10.1159/000065642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Werdelin L, Keiding N. Hereditary ataxias: epidemiological aspects. Neuroepidemiology 1990;9:321–31. 10.1159/000110795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vaeth M. Basal demografisk metode. Kompendium [In Danish]. Aarhus: Department of Public Health, Aarhus University, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patzkó A, Shy ME. Update on Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2011;11:78–88. 10.1007/s11910-010-0158-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vallat JM, Mathis S, Funalot B. The various Charcot-Marie-Tooth diseases. Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26:473–80. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328364c04b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abboud L, El SF, Takubo T, et al. Phrenic nerve involvement in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Tenn Med 2005;98:495–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.