Abstract

Background and Objectives

This review aimed to inform the current state of alcohol research on the joint effects of genes and the environment conducted in U.S. racial/ethnic minority populations, focusing on African Americans, Latinos/Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians.

Methods

A key-word and author-based search was conducted and supplemented with direct contact to researchers in this area to ensure a comprehensive inclusion of published, peer-reviewed studies. These studies were considered in terms of the racial/ethnic population groups, phenotypes, genetic variants, and environmental influences covered. Research findings from alcohol epidemiologic studies were highlighted to introduce some potential environmental variables for future studies of gene and environment (G–E) relationships.

Results

Twenty-six (N=26) studies were reviewed. They predominantly involved African American and Asian samples and had a very limited focus on Latinos/Hispanics and American Indians. There was a wide range of alcohol-related phenotypes examined, and studies almost exclusively used a candidate gene approach. Environmental influences focused on the most proximate social network relationships with family and peers. There was far less examination of community- and societal-level environmental influences on drinking. Epidemiologic studies informing the selection of potential environmental factors at these higher-order levels suggest inclusion of indicators of drinking norms, alcohol availability, socioeconomic disadvantage, and unfair treatment.

Conclusions

The review of current literature identified a critical gap in the study of environments: There is the need to study exposures at community and societal levels.

Scientific Significance

These initial studies provide an important foundation for evolving the dialogue and generating other investigations of G–E relationships in diverse racial/ethnic groups.

Keywords: race, ethnicity, gene-by-environment interactions, alcohol use, alcohol use disorder

1. Introduction

There is a recognizable shortage of genetic studies of alcohol consumption and related phenotypes in U.S. racial/ethnic minority populations (the focus of this special issue). This is occurring alongside a growing interest in understanding how environmental conditions enhance or reduce genetic effects in light of long-held evidence that sociocultural factors and the built environment are associated with levels of alcohol consumption and risk for related problems in U.S. racial/ethnic minority populations (e.g., Karriker-Jaffe et al.1, Zapolski et al.2, Zemore et al.3). The current review seeks to bring together two large areas of alcohol research in racial/ethnic minority populations. The first are studies of relationships between genes and the environment (G–E) and the second are alcohol epidemiologic studies, and both literatures include a range of features of drinking, from normative behaviors to binge or heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD).

We conceptualize G–E relationships from an integrated perspective, to mean that genetic and environmental effects come together (in different ways) to contribute to alcohol-related phenotypes4. Three fundamental relationships include: 1) additive effects of genes and the environment; 2) gene-environment correlations; and 3) gene × environment interactions (G×E). An additive relationship is characterized by independent genetic and environmental contributions to an alcohol outcome. Gene-environment correlations and G×E, respectively, describe mediation and moderation relationships in predicting an outcome. A gene-environment correlation identifies a selection effect where genetic vulnerability is associated with exposure to an environment. GxE relationships indicate that genetic vulnerability – or protection – can vary depending on the level of environmental exposure, or, equally, that the effect of the environmental exposure can be different depending on genotype.

The study of GxE relationships has garnered attention and excitement, but also caution and concern5,6. Therefore, we seek to encourage careful and systematic analyses of G–E relationships as an important tool to further our understanding of the complex etiology of AUD and to identify environmental targets for prevention and intervention efforts. Previous papers have outlined recommendations for rigorous GxE research practices (e.g., Dick et al.5). We focus here on the selection of environmental factors that have both theoretical plausibility and empirical precedent for inclusion in the study of G–E relationships.

This report begins with a presentation of two theoretical mechanisms for conceptualizing environmental influences on alcohol consumption and related phenotypes, offered as a model to help synthesize and critique the extant literature in this area. We then review studies that have tested hypotheses about the interplay between measured genes and the environment in U.S. racial/ethnic minority populations, focusing on African Americans, Latinos/Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians. By measured gene studies, we refer to those that have used molecular methods and examined genetic variation in a given region or at a specific marker on a chromosome. (See Agrawal et al. in this issue for a discussion of latent genetic studies using twin designs.) However, because these genetic studies are few, we also identify some key environmental exposures shown to be associated with greater risks or protections for drinking and AUD in these populations.

2. Theoretical mechanisms

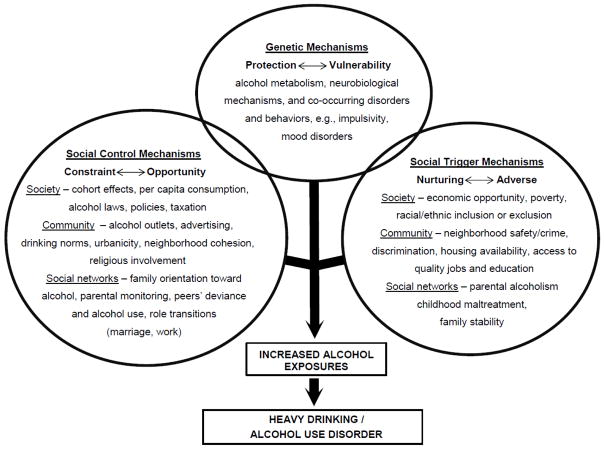

We use the term environment to broadly refer to community- or societal-level factors like per capita alcohol consumption, drinking norms, and alcohol outlet density, as well as social network factors like peer relationships and family circumstances (e.g., childhood abuse/neglect). This conceptualization of the environment is consistent with a multi-level perspective on health7,8 and risk behavior including substance use9 in that we emphasize contexts in which individuals are embedded, including peer groups, organizations, physical and social spaces, and the broader culture. This multi-level perspective is reflected in the model presented here (See Figure 1) as a means of organizing environmental exposures across three spheres of influence: social network, community, and societal. Additionally, we categorize these environments under two central mechanisms, social control and trigger, that are thought to modify genetic predisposition to AUD and that have previously been the focus of GxE studies. Earlier literature (e.g. Dick & Kendler10, Shanahan & Hofer11, and Sher et al.12) offers a solid place to start in identifying examples of environmental social controls and triggers important to AUD, although issues relevant to specific racial/ethnic groups have not been widely considered in prior research. Therefore, here, we sought to introduce these mechanisms in order to set the stage for a wider discussion of environmental conditions related to alcohol use for racial/ethnic minority groups.

Figure 1.

Theoretical mechanisms for genetic and environmental influences on AUD

Social control

Elements of social control include both protective and risk environments that primarily operate to constrain or enable opportunities to use alcohol, thereby influencing the contribution of genetic effects to AUD. Shanahan and Hofer11 emphasized elements of social control such as social norms or structural constraints that help maintain social order by decreasing deviant behaviors such as excessive alcohol use. They highlighted involvement with community institutions including churches and social norms surrounding alcohol use. For example, the Higuchi et al.13 study is often highlighted in discussions of the relationship of societal-level effects on genetic influences for alcoholism, as the protective ALDH2*2 variant was reported to be weaker in younger Japanese cohorts, suggesting a link to more liberal drinking norms and an increase in per capita alcohol consumption. In the U.S., there is evidence for strong cohort effects on drinking, with some birth cohorts drinking much more heavily than others14,15; however, corresponding studies in U.S. samples on the relationship of these changes to genetic influences for alcohol use have not been conducted. Dick and Kendler10 and Sher et al.12 also underscored more proximate environmental social controls related to peer and family networks, including role transitions like marriage or marriage-like relationships, parental monitoring, and relationships with deviant or antisocial peers. Kendler et al.16 showed that low parental monitoring and high peer deviance were associated with increased genetic influences on alcohol use in youth. Similar social control processes also may be happening on the community level. Neighborhood environments characterized by urbanicity and increased access to alcohol (which have been associated with increased genetic influences on alcohol consumption) may be associated with lower monitoring and control of others’ behavior, particularly in concert with high residential mobility16,17.

Social trigger

By contrast, adverse environmental conditions may act as social stressors that trigger or strengthen genetic effects for AUD; evidence points to an individual’s responsiveness or sensitivity to stressful conditions being influenced by genetic factors18. Nurturing environments conceptually may be placed at the other end of this spectrum, but have not been the focus of G–E studies of AUD. For example, Turkheimer et al.19 examined a continuum of socioeconomic conditions, showing different relationships for genetic and environment effects with intelligence when comparing impoverished and affluent family environments. Conversely, studies of GxE triggering mechanisms for AUD, as well as for major depression and aggression, have focused more on contextual variables like stressful life events and childhood maltreatment10,11. Two recent measured-gene studies identified significant interactions between genetic effects and childhood adversities (e.g., abuse, parental divorce or death, witnessed violence) in predicting AUD: Meyers et al.20 and Sartor et al.21 reported, respectively, an enhanced association of the ADH1B risk variant and a reduced association of the ADH1B protective variant with AUD under adverse childhood conditions. These studies are complemented by evidence suggesting strong main effects of these stressors on AUD, including robust evidence for adverse effects of early child abuse and parental loss on alcohol outcomes in adulthood22–24. Additional indicators of environmental stress may be relevant moderators of genetic influences, including at community and societal levels. Boardman et al.8 suggest a reframing of the ‘environment’ in studies of G–E relationships to include macro-level factors that characterize where people live and work when assessing their exposure to risks and resources. One potential trigger for AUD is neighborhood disadvantage, which has consistently been associated with illicit drug use, and in some studies has also shown associations with heavy drinking and AUD25. Later we return to a discussion of neighborhood disadvantage as an environmental variable that may be relevant to studies of AUD and G–E relationships for ethnic/racial minority populations.

3. Studies of joint G–E effects in U.S. ethnic minority populations

We conducted a focused survey of the peer-reviewed, published literature for measured gene and environment alcohol studies that focus on U.S. racial and ethnic minority populations to inform the current state of the science in this area. The results of our literature review are presented in Table 1. Key terms for this search included “gene-environment”, “gene × environment”, “alcohol”, “substance use”, “divers*”, “ethnic*”, “race”, “racial”, “Latin*”, “Hispanic”, “African American”, “Asian American”, “Native American”, and “American Indian”. The primary search engine used was Google Scholar. In addition, an author search based on key researchers in this area was conducted and a number of researchers were contacted directly to explore any current research efforts being conducted and additional relevant researchers that should be considered. Below, we have reviewed the identified studies in terms of the racial/ethnic population groups, phenotypes, genetic variants, and environmental influences studied. We also present some of the challenges for GxE research evidenced in these studies.

Table 1.

Studies of genetic and environmental influences with diverse population groups: Summary characteristics

| Citation | Sample Size (subgroups) | Age Group | Gene | Drinking Phenotype* | Environmental Influences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Triggers | |||||

| African American | ||||||

| Beach et al., 2010 | 337 | Youth | DRD4 | Substance Use** Drank alcohol, 3+ drinks at one time, and smoked marijuana |

Social Network: Intervention status - Strong African American Families program |

|

| Brody et al., 2009a | 641 | Youth | SLC6A4 | Risk Behavior Initiation** Ever drank alcohol, used marijuana, or had sexual intercourse |

Social Network: Intervention status - Strong African American Families program |

|

| Brody et al., 2009b | 253 | Youth | SLC6A4 | Substance Use** Smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol, 3+ drinks at one time, and smoked marijuana |

Social Network: Supportive parenting, involvement, and good communication |

|

| Brody et al., 2013 | 963 | Youth and adolescents | DRD2, DRD4, ANKK1, GABRG1, GABRA2 | Alcohol Use** Drank alcohol and 4+ drinks at one time |

Social Network: Intervention status - Strong African American Families program |

|

| Brody et al., 2015 | 291 | Adolescents | DRD4 | Substance Use** Cigarette, alcohol, marijuana, and other drug use in past month |

Social Network: Intervention status - Adults In the Making program |

Social Network: Family risk - Parent-child conflict/communication, chaos in home, caregiver depression, and parental support |

| Enoch et al., 2010 | 563 | Adult men | GABRA2 | 1) Alcohol; 2) Heroin; and 3) Cocaine dependence |

Social Network: Childhood abuse or neglect |

|

| Goyal et al., 2016 | 541 | Adolescents | CRHBP, NR3C1 | Alcohol use** Frequency and quantity of any alcohol use, and frequency of 5+ drinks in a couple of hours |

Social Network: Stressful life events§ - Life transitions (e.g., marriage, baby) |

Social Network & Community Level: Stressful life events§ - Property damage, disruption in home, illness or injury, family/friend death or illness, victim of crime, witnessed violence, exposure to neighborhood violence |

| Kranzler et al., 2012 | 564 (African, Afro- Caribbean, and African American) | College students | SLC6A4 | 1) Any drinking; and 2) Heavy drinking frequency (males 5+ drinks, females 4+ drinks) |

Social Network: Stressful life events - Relationship, academic, family health, and financial problems |

|

| Asian American | ||||||

| Bujarski et al., 2015 | 97 (Chinese, Korean, and Japanese) | College students | ALDH2, ADH1B | Alcohol use** Frequency and quantity of any alcohol use, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol- related consequences |

Social Network: Parental history of alcoholism§§ Community Level: 1) Ethnicity; and 2) Acculturation |

Social Network: Parental history of alcoholism§§ |

| Hendershot et al., 2005 | 428 (Chinese and Korean) | College students | ALDH2 | 1) Frequency and quantity of any alcohol use, and 2) Heavy episodic drinking (males 5+ drinks, females 4+ drinks) |

Social Network: Parental alcohol use Community Level: Ethnicity |

|

| Irons et al., 2007 | 34 (Korean adoptees) | Adolescents and young adults | ALDH2 | 1) Past-year drinking; and 2) Past-year drunkenness |

Social Network: 1) Parental history of alcoholism§§; and 2) Sibling alcohol use |

Social Network: Parental history of alcoholism§§ |

| Irons et al., 2012 | 356 (Korean adoptees) | Adolescents and young adults | ALDH2 | 1) Alcohol Use** Drinking frequency and quantity, maximum drinks consumed on one occasion, frequency of intoxication; 2) Alcohol abuse & dependence symptom count; and 3) Alcohol abuse or dependence diagnosis |

Social Network: 1) Deviant peer behaviors; 2) Parental alcohol use problems§§; and 3) Elder sibling alcohol use problems |

Social Network: Parental alcohol use problems§§ |

| Luczak et al., 2003 | 347 (Chinese and Korean) | College students | ALDH2 | Heavy episodic drinking (males 5+ drinks, females 4+ drinks) |

Community Level: 1) Religious services attendance; and 2) Ethnicity |

|

| Latino/Hispanic | ||||||

| Du et al., 2009 | 703 (Mexican American) | Adults | SLC6A4, OPRM1, A118G, DRD2 | 1) Maximum drinks consumed in a 24-hour period; and 2) Alcohol abuse or dependence |

Social Network: Marital status Community Level: Educational attainment |

|

| American Indian | ||||||

| Ducci et al., 2008 | 291 (Southwest American Indian) | Adult women | MAOA | Alcohol use disorder |

Social Network: Childhood sexual abuse |

|

| Enoch et al., 2006 | 342 (Plains American Indian) | Adults | COMT | Alcohol use disorder and nicotine addiction** |

Community Level: Gender |

|

| Multiple Population Sample | ||||||

| Chartier et al., 2016 | 7,716 (Combined African, European, and Hispanic American sample) | Adults | ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4 | 1) Maximum drinks consumed in 24-hours; and 2) Alcohol dependence symptoms |

Community Level: Religious services attendance |

|

| Daw et al., 2013 | 14,560 (Combined Black, White, Hispanic, Asian, and other sample) | Adolescents and young adults | SLC6A4 | 1) Drinking frequency, and 2) Drinking quantity |

Community Level: School-level drinking |

|

| Dick et al., 2006 | 1,916 (Combined African and European American sample) | Adults | GABRA2 | Alcohol dependence |

Social Network: Marital status |

|

| Kaufman et al., 2007 | 127 (Combined African, European, and Hispanic American, and biracial sample) | Youth and adolescents | SLC6A4 | 1) Alcohol use yes/no; 2) Age of first use; and 3) Episodes of intoxication |

Social Network: 1) Childhood maltreatment; and 2) severity of childhood maltreatment |

|

| Lieberman et al., 2016 | 1,845 (Combined African, European, and Hispanic descent sample) | College students | FKPB5 | Heavy drinking (males 5+ drinks; females 4+ drinks) averaged from daily report across 29 days |

Social Network: Past- year life stress§ - relationship, health, and financial problems Social Network & Community: 1) Early life trauma§ and 2) past-year trauma§ - accident, illness, disaster, war, violence/victimization, loss/separation |

|

| Luczak et al., 2001 | 108 (Chinese); 124 (Korean); and 96 (White) | College students | ALDH2 | Binge drinking |

Community Level: Ethnicity |

|

| Luczak et al., 2004 | 190 (Chinese); 214 (Korean); and 200 (European heritage) | College students | ALDH2, ADH1B | Alcohol dependence |

Community Level: 1) Gender; and 2) Ethnicity |

|

| Olfson et al., 2014 | 1,550 (Combined African and European American sample) | Adolescents | ADH1B | 1) Age of first intoxication; and 2) Age of first alcohol use disorder symptom | Social Network: Peer drinking | |

| Sartor et al., 2014 | 2,617 (African American); and 1,436 (European American) | Adults | ADH1B | 1) Maximum drinks consumed in 24-hours; and 2) Alcohol use disorder symptom count | Social Network & Community: Childhood adversity§ - Parental death, sexual or physical abuse, and witnessed or experienced violent | |

| Vaske et al., 2009 | 402 (African American); and 1,552 (Caucasian) | Adolescent and young adult | DAT1 | Problems (because of drinking)** At school or work, with friends or partner, hung over, sick, physical fights, and risky sexual behavior |

Social Network: Paternal history of alcoholism§§ |

Social Network: Paternal history of alcoholism§§ |

Notes:

Numbered phenotypes reflect studies that examined multiple outcome measures;

Phenotype was a composite measure of more than one alcohol or drug use or risk behavior outcome;

Items in composite measure of environment could be individually classified as constraints or triggers or as social network or community level exposures; and

Parental alcoholism is associated with known environmental risk factors for AUD that could be classified as constraints or triggers.

Population groups, phenotypes, and genetic variants covered

There were a limited number of studies addressing this topic, but even among those identified some population groups were more represented than others. Predominantly, studies involved African American26–33 or Asian American34–38 samples. There was a very limited focus on Latinos/Hispanics (one study on Mexican Americans39) and American Indians (two studies identified40,41). Additionally, across population groups, most samples included younger subjects, for example, older children and adolescents. Studies including adults fell into two categories, with most being conducted with young adult/college student samples and fewer involving samples representing a wide range of adult ages.

Due to the relative paucity of research in this area, the scope of the literature review was expanded to include studies with some degree of racial or ethnic diversity. Some of these studies reported G–E results separately for each population included21,42,43, while others reflected the results of a combined sample44–49. These multi-population studies primarily included European Americans and African Americans, although some did include subjects of Latino/Hispanic or Asian descent. The search was also expanded to studies that examined both alcohol and other substance use phenotypes26,27,29–31,40. Therefore, the included studies either examined alcohol use discretely or as a part of a composite measure of substance use or risky behavior.

Studies of GxE relationships face a number of limitations to which the identified studies are vulnerable. These include challenges with small sample sizes, related concerns about false positive findings and the replicability of results, statistical and conceptual issues about the nature of the interaction, and publishing biases5,6,50,51. Therefore, excluding several large studies that used combined samples of more than one population, study sample sizes for racial/ethnic minority groups were as small as 34 and 97 subjects and otherwise ranged from 108 to 703, with two larger samples including 963 and 2,617 subjects. Ideally, sample sizes greater than 1,000 participants are recommended to help protect against potentially spurious GxE effects5, although the realities of limited resources and restricted access to some population groups can provide a challenge to robust sample sizes. To address this concern, Argawal et al.52 promote greater consistency in the phenotypic measures utilized across studies, which would allow for the harmonization of results and meta-analysis across studies to provide more confidence in the findings drawn. However, even in the small number of studies reviewed here, one can note the wide variation in phenotypes that were examined, which ranged from different measures of alcohol consumption and alcohol use diagnoses to complex composite measures of more than one alcohol or drug use outcome.

Additionally, these studies relied almost exclusively on a candidate gene approach. Examples of the genes studied are SLC6A4 (i.e., the short, long 5-HTTLPR variant); DRD4; GABRA2; ADH1B; and ALDH2. Unfortunately, the replication of findings from candidate GxE studies can be challenging; most often noted are inconsistencies reported for the relationship between the 5-HTTLPR variant and stressful life events (see Duncan and Keller6 and Dick et al.5 for an expanded discussion of this topic). Some studies did examine candidate genes with relatively well-understood biological mechanisms related to alcohol consumption and AUD (e.g., ADH1B and ALDH2; see Hurley et al.53), and a few tested multiple markers or a sum score of risk variants across multiple genes28,45. However, other techniques, including polygenic risk scores that aggregate the effect of a number of gene markers, offer researchers newer alternatives that could help to increase confidence in the genetic associations that are being studied54,55. Studies using a polygenic score approach were not represented in the literature we reviewed.

Environmental influences

The environmental influences examined across these studies were considered, based on our organizational framework in Figure 1, for their representation of the mechanisms of social controls and triggers and our three levels of environmental influence (social network, community, and societal). In the sections below, we provide an overview of the environmental influences covered. Additionally, Table 2 presents relevant key findings for the genetic and environment effects studied and their inter-relationships. These studies point to some inconsistencies and mixed findings that underscore the need for further replication and other empirical support. There may be many reasons for these differences11, which are perhaps unsurprising based on the earlier challenges discussed (e.g., sample size, variations in phenotypic measures). Alcohol use in some population groups could also be less affected by certain genetic or environmental factors, including when samples involve younger subjects early in their development of drinking behaviors35. Regardless, this research does provide an important foundation for evolving the dialogue in this area. These initial studies hopefully will serve to generate other investigations of G–E relationships in diverse racial/ethnic population groups.

Table 2.

Key findings from studies of G–E relationships by environmental feature and level

| Feature | Social Network Level |

|---|---|

| Parental alcoholism | Interaction between parental alcohol problems and protective genetic variant against drinking in Asians observed in some studies (Bujarski et al.34; Irons et al.35). Additive and interactive G–E relationships for parental alcoholism may be different across gender and population groups (Vaske et al.43). |

| Parenting skills intervention status | Genetic variants were associated with differential responsiveness to interventions targeting more communicative and involved parenting for African American youth (Brody et al.27–30; Beach et al.26). |

| Sibling alcohol use | Sibling alcohol use was a significant predictor of reduced ALDH2*2 protection against drinking (Irons et al.35,36), but non-significant findings were encountered when examining phenotypes for AUD35. |

| Marital status | Evidence of both G–E correlation and interaction effect in Dick et al.46, but no G–E relationships in Du & Wan39. |

| Peer alcohol use | Reduced protective ADH1B effect when reporting that most or all peers drink in African and European American adolescents (Olfson et al.44). ALDH2 was not correlated with peer deviance; more consistent evidence for a G–E additive relationship with alcohol-related phenotypes (Irons et al.35). |

| Childhood maltreatment | Evidence for an interaction between childhood abuse and genetic risk by some (MAOA, Ducci et al.41; SLC6A4, Kaufman et al.47), but not all studies (GABRA2, Enoch et al.31). GABRA2 did not correlate with childhood trauma. |

| Social Network & Community Level* | |

| Adverse life events | Mixed support for joint effects between genes and adverse life events based on genetic variant, gender, and race/ethnicity, respectively, demonstrating a moderating effect for CRHBP (Goyal et al.32), African American females (Kranzler et al.33), and European American males (Sartor et al.21) only. Early life trauma, but not past-year trauma or stress, interacted with FKBP5 on heavy drinking in college students (Lieberman et al.49). |

| Community Level | |

| Religious involvement | Evidence of reduced genetic risk for drinking with greater religious services attendance (Chartier et al.45; Luczak et al.37) |

| Social drinking norm indexes | Higher school-level alcohol use interacted with SLC6A4 genotype to predict greater alcohol consumption (Daw et al.48). Acculturation predicted more drinking with no interactive effect (Bujarski et al.34). Studies of ethnicity, gender, and educational level reported mixed additive (Luczak et al.57) and interactive (Du & Wan39; Enoch et al.40) effects as well as no G–E relationships (Hendershot et al.38). |

Notes: G–E = gene-environment;

adverse life events were classified as social network and community level exposures due to the items included in the composite variable; and none of the studies reviewed examined environmental features at the societal level.

Social networks

There was considerable attention given to the most proximate social network influences, as both constraints and triggers. Environmental variables at this level were characterized by parental influences34–36,38,43, including parental alcoholism, which, framed within the context of our model, presents both potentially controlling and triggering influences. Parental alcoholism, for example, may foster conditions where alcohol is more accessible and drinking is more acceptable or that contribute to a turbulent and stress-inducing home environment. However, this environmental influence is strongly confounded with genetic effects, unless examined using highly robust designs to isolate genetic and environmental factors, e.g., an adoption paradigm (see Irons et al.35). Also examining the role of parental influence, there was a subset of randomized studies that examined interventions targeting parenting skills26–30, including communication skills around risks and expectations for substance use and providing emotional support and instrumental assistance to children.

Social-network level variables also focused on other family relationships35,36,39,46, including marriage and sibling relationships, and peer influences35,44. Genetic factors can inter-relate with marital status or peer groups in influencing alcohol use and AUD through both gene-environment correlations and GxE effects46,56. These factors all potentially contribute to varying degrees of increased or decreased constraint related to access to alcohol and perceived permissiveness for drinking in the immediate environment.

Adverse life events were a prominent environmental (triggering) variable across many of the studies21,31–33,41,47,49. As a category, they represented a number of different experiences: childhood maltreatment; early life trauma; life transitions; experiences of illness and death; disruptions in the home; and witnessing/exposure to family violence. These risk factors sometimes extended beyond social network influences to include exposure to violence and crime at the community or neighborhood level (e.g., Goyal et al.32, Sartor et al.21). Generally, composite measures of stressful life events incorporated a wide variety of circumstances, which can complicate the understanding and isolation of environmental exposures that contribute to a GxE effect12.

Community

Only a handful of studies examined how broader social influences on drinking may influence the relationship between genetic risk or protection and alcohol use. These studies included the use of variables related to religious involvement and school-level (e.g., high school) drinking37,45,48 to examine the effects of instituational social control and group-level social drinking norms. At this level, we also included several studies that used membership in various social groups34,38–40,42,57, like ethnicity, gender, and level of education as indirect measures indexing group differences in social norms about drinking or vulnerability to environmental stressors. However, these variables can be difficult to assess as cultural indicators in G–E associations. Ethnicity may be confounded by population stratification, as the pattern of association between alleles (linkage disequilibrium) and genotype frequencies can vary across ancestry groups42,45, and gender may indicate other biological features (e.g., sex hormone levels)40. Level of education also has a complex relationship with alcohol-related phenotypes, both as a moderator of genetic effects and through shared genetic influences with alcohol problems58. One study examined acculturation34, which also may gauge changes in social drinking norms tied to exposure to mainstream American culture.

Societal

Even more striking was the absence of higher-order societal variables, for both social control and trigger mechanisms. This runs contrary to historic understandings that structural influences and differential exposures to risks and access to resources are related to the health differences experienced by racial/ethnic minority groups59.

4. Some considerations when selecting an environment

The above review of the current literature identified a critical gap in the study of environments: There is a need to include exposures at community and societal levels8. Some environmental conditions are also potentially more relevant to racial/ethnic minority populations. We start here by offering a few key considerations for selecting an environmental factor for inclusion in a G–E relationship study, and then highlight research findings from alcohol epidemiologic studies to introduce some potential environmental variables, at these higher levels of influence, that have not been previously studied in this manner.

Fit with a theoretical mechanism

There has been some debate as to whether it is important to establish a link between an environmental exposure and the neurobiological changes associated with the psychiatric disorder being studied60. We do not weigh in on that here; existing literature provides an examination of proposed pathways of environmental exposure to neurobiological functioning and the association with alcohol use, relapse, and recovery (e.g., Koob & Volkow, 201661; Seo & Sinha, 201562). Research on neurobiological changes is more consistently linked to social triggers like stress and trauma, but social control influences, such as those studied by Brody and colleagues26–30, may offer actionable targets for intervention. Here, we contend that for G–E studies of AUD, environmental conditions should be logically associated with changes in both exposure to alcohol and levels of drinking (see Figure 1). This could mean that an environmental feature increases risk for greater alcohol exposure and a resultant escalation of drinking, or it may be protective and decreases drinking. Such conditions can occur at the social network, community, and societal levels, but identification of plausible mediating mechanisms from higher-order (community or societal) factors to changes in alcohol consumption is needed. Social control mechanisms, compared to social triggers, may offer a strong theoretical link to changes in opportunities to use alcohol. Studies of adolescent psychiatric symptoms63 and alcohol use64, for example, point to intermediate social control influences (parental supervision and peer delinquency) that help explain the triggering effects of poverty and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage.

Ability to rule out alternative explanations

One end goal for this area of research is the identification and understanding of causal environmental influences on genetic effects as targets for prevention and intervention efforts. The selection of environmental features for G–E studies should consider fundamental conditions for causality including statistical association, time order of relationships, and whether there are other plausible explanations65. Particularly relevant to this topic are gene-environment correlations as alternative explanations for a GxE effect5. A classic example is the correlation between genetic susceptibility for alcohol use and the selection into a deviant peer group56. At the community level, a related phenomenon is the selection of people who drink heavily into more disadvantaged areas over time66, which is likely to happen in addition to neighborhood causal effects on heavy drinking and AUD. To rule out alternative explanations in GxE studies, it is therefore advantageous to select environmental features that are exogenous to the individual and that exclude individual choice whenever possible.

Ability to predict phenotype variability

The selected environmental exposure must be predictive of phenotype variability60. This point is straightforward, but should be extended to take into consideration the specific subgroup being studied. In order to examine the inter-relationships between genetic and environment effects, a predisposing or protective environment must be selected that varies in the targeted population group. For instance, while protective effects for religion are widely documented for African Americans67–69, as well as Latinos/Hispanics and Whites70, genetic studies of AUD that include highly-religious subgroups, such as rural and Southern African Americans or immigrant and first-generation Latinas, should carefully assess whether respondents have had enough exposure to alcohol to test G–E relationships. Certain religious affiliations (such as Southern/American Baptist, conservative Protestant, fundamentalist Christian, Mormon, Muslim, and others) are strongly associated with abstinence from alcohol71.

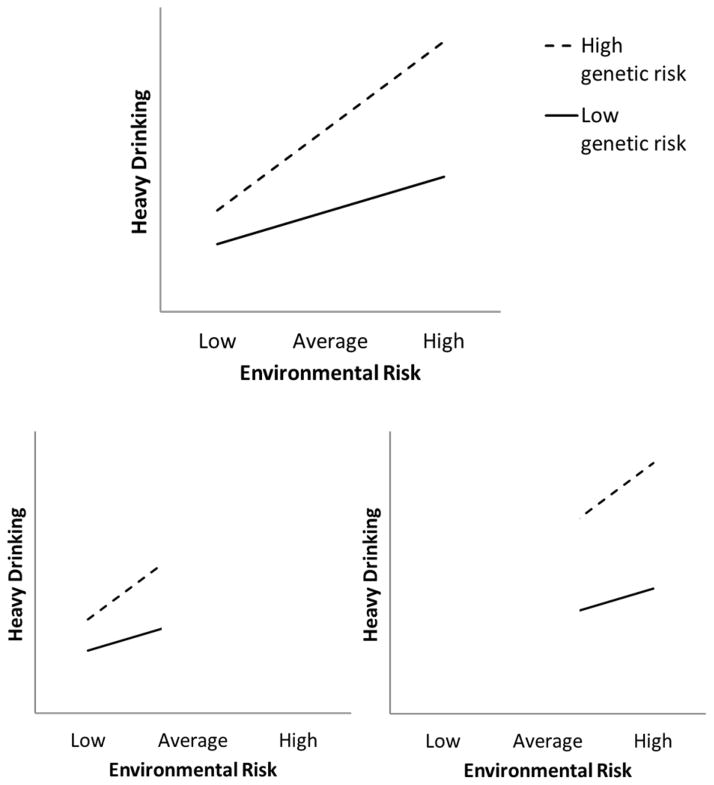

The consideration of variability can also be extended to provide an explanation for why GxE effects might be observed in one racial/ethnic group but not another. Social control and social trigger mechanisms, according to Dick and Kendler10 and Boardman et al.8, predict reduced genetic influences under low-risk environmental conditions and, conversely, increased genetic influences under more adverse conditions (illustrated in Figure 2, top panel). GxE effects are more likely observed in population groups when members are represented along the continuum of low- to high-risk environments, and less likely when members are overly represented at any single point along the continuum, whether more low-risk or adverse (illustrated in Figure 2, bottom left and right panels, respectively). Alike, selected genetic marker(s) must vary in the targeted population, with GxE effects being more likely observed when, in the case of biallelic markers, the frequencies of the common and minor alleles are more balanced. See Duncan and Keller6 for a more detailed illustration of the relationships between sample size, variance, and statistical power to detect GxE effects.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical fan-shaped GxE relationship for full distribution of environmental risk (top), compared to truncated distributions for low-risk (bottom left) and high-risk environments (bottom right)

Developmental timing of exposure

Developmental timing of environmental exposures is another important consideration for G–E studies, and evidence suggests that sensitive developmental periods may differ for U.S. racial/ethnic subgroups due to differences in alcohol use over the lifespan. One longitudinal study of a U.S. national sample72 showed an upward trend in heavy drinking by African Americans and, to a lesser extent, Latinos/Hispanics occurring in their 30s. This trend was accompanied by an increase in alcohol problems among African Americans starting in their mid-20s into their late 30s, which eventually exceeded those of Whites and Latinos/Hispanics. Thus, when assessing G–E relationships in groups with later onset of drinking, timing of the environmental exposure assessment should coincide with the periods in which the individuals may be starting to drink or escalating their alcohol use.

5. Special consideration of select environments for U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups

When we consider racial/ethnic minority groups, additional indicators of environmental social control and trigger mechanisms may be potential moderators of genetic influences. In this section we will consider selected environments for which there is empirical precedent, including evidence of strong main effects for greater risk of heavy drinking and AUD in racial/ethnic minority groups, or evidence that the environmental influence may be more important for racial/ethnic minority subgroups than for Whites. These may be strong candidates for study in G–E relationships. Additionally, social contexts that constrain drinking also are important to consider in analyses of G–E effects on AUD.

Social control

Social norms about drinking

Many studies suggest that social norms and attitudes about drinking have fairly uniform associations with alcohol use and problems across gender and race/ethnicity73,74. When considering racial/ethnic minority groups, additional norm-related cultural elements may be relevant as environmental modifiers of genetic risk. Among Asian Americans, ethnic drinking culture tied to the country of origin, measured by per capita alcohol consumption, is associated with heavy drinking and drunkenness for certain subgroups such as Korean and Japanese adolescents and adults75. Acculturation and birthplace also are predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol problems among some Latino/Hispanic76 (particularly women) and Asian77 subgroups living in the U.S. Among African Americans, elements of ethnic identity, or the affiliation and identification with people of common ancestry, language and religion in different social and civic contexts, also are associated with religiosity, drinking norms and alcohol consumption78. Protective effects on AUD of ethnic and cultural identity (or enculturation) also have been documented for some American Indian groups79.

At the neighborhood level, co-ethnic density may be a protective factor or a risk factor, depending on the specific racial/ethnic group in question. A higher density of African Americans may be a risk factor contributing to heavy drinking80, but a higher density of Latinos/Hispanics may be a protective factor81. In addition to the social context, physical drinking contexts may contribute to heavy drinking, perhaps through influences on perceptions about behaviors that are normative in that setting. As examples, drinking at bars and parties may encourage drinkers to drink more heavily or more quickly than they might do during a quiet evening at home. Compared to Whites, Latinos/Hispanics and Blacks tend to drink in public more frequently and to consume higher volumes in these settings82. It may be useful to assess contexts where people drink to supplement information on social norms about drinking for G–E studies.

Alcohol availability

As alcohol availability increases, alcohol consumption also increases. Alcohol availability can be operationalized based on respondent-reported perceptions or using objective administrative data. Studies using objective measures suggest neighborhood alcohol outlet density is associated with greater alcohol consumption83 and alcohol problems84. Similarly, greater neighborhood drug availability can increase substance use85, alcohol dependence86, and drug abuse relapse87. Some evidence suggests African Americans may be at even higher risk than other groups for alcohol-related health problems in areas with higher densities of off-premise alcohol outlets84. In addition to increasing alcohol availability, a high density of alcohol outlets also may operate as a trigger for heavy drinking or as a stressor, as some evidence suggests a proliferation of alcohol outlets can increase violence in the surrounding area84,88.

Other factors influencing alcohol availability are state licensure and tax structures, as well as alcohol advertising. Higher alcohol prices are associated with reductions in heavy drinking and alcohol problems, particularly among adolescents and young adults89. Low-income youth may be especially sensitive to alcohol prices; this may manifest in stronger deterrent impacts of higher alcohol taxes on drinking of racial/ethnic minority youth and adults. Regarding advertising, evidence suggests that youth delay drinking and drink less frequently in areas with more restrictive policies about alcohol marketing90, and some studies also have found greater exposure to alcohol advertising is associated with increased consumption, particularly by youth83. Neighborhoods with a high density of African Americans (which often are economically disadvantaged) are selectively targeted for marketing of high-alcohol content beverages such as malt liquor beer and spirits91,92. Indicators of local alcohol availability, including tax policies and advertisements for alcohol, are good candidates for studies of G–E relationships in racial/ethnic minority populations as they are likely to be exogenous exposures, particularly for youth and young adults.

Social triggers

Socioeconomic disadvantage

Socioeconomic disadvantage93,94, long-term poverty95,96 and cumulative disadvantage97 from multiple sources are associated with heavy drinking and alcohol problems, and experiencing multiple and persistent forms of socioeconomic disadvantage across childhood and into adulthood is associated with heavy drinking and alcohol problems in adulthood98. In the U.S., African Americans have much higher rates of poverty than Whites, and they also are more likely to experience long-term poverty99. These socioeconomic risk factors for alcohol problems may be stronger for Blacks and Latinos/Hispanics than Whites100,101.

Neighborhood poverty also can be a stressor that increases alcohol use and problems (or, as an alternative explanation, heavy drinkers may select into certain neighborhoods). In one longitudinal study of young adults, there was a strong effect of cumulative exposure to neighborhood poverty over 20 years on heavy alcohol use, but acute exposure to neighborhood poverty also increased heavy alcohol use102. African Americans are more likely than Whites to live in poor neighborhoods103,104. Stronger associations of neighborhood disadvantage with alcohol use and alcohol problems have been noted for African Americans than for Whites or Latinos/Hispanics1,101, with neighborhood disadvantage associated with less heavy drinking by White adult drinkers, but more heavy drinking by African American drinkers and marginally more heavy drinking by Latino/Hispanic drinkers1. In addition to neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, neighborhood disorder is associated with many substance use outcomes105, including heavy drinking106,107. Thus, indicators of socioeconomic status encompass multiple levels of exposure across the lifecourse, including both acute and chronic disadvantage.

Racial discrimination and stigma

Racial discrimination is a stressor that contributes to adverse mental health and risk behaviors in adults and youth108. Racial discrimination and perceived racial/ethnic stigma can increase heavy consumption, alcohol abuse, and drinking problems among Blacks and Latinos/Hispanics109,110. Mulia et al.97 and Chae et al.111 examined the related constructs of perceived ethnic group stigma and unfair treatment, and found positive relationships for these variables in predicting problem drinking among Blacks, Latinos/Hispanics, and Asians. Among American Indians, discrimination may be associated with feelings of historical loss associated with long-term, intergenerational impacts of genocide and cultural “reformation” of American Indians in the U.S.; these stressors are associated with adverse alcohol outcomes including AUD79,112.

Co-occurrence of environmental triggers

Socioeconomic status, racial discrimination, and neighborhood disadvantage often are closely related, with race/ethnicity impacting all three113,114. The Mulia et al.97 study detailed above found that experiencing multiple forms of social adversities (racial/ethnic stigma, unfair treatment, and poverty) increased risk for problem drinking across ethnic groups. Zemore et al.3 showed that adversities accumulate in their association with alcohol problems: Specifically, unfair treatment for Blacks and perceived ethnic stigma for Latinos/Hispanics each were associated with alcohol problems among those living below the poverty level but not above. At the neighborhood level, there also is co-occurrence with certain environmental constraints. Disadvantaged neighborhoods often contain an excess of alcohol outlets115,116. We also note that low-income minority communities may be more likely to have more liquor stores, while low-income white communities may be more likely to have more bars117; thus, choosing the most appropriate measure(s) of alcohol availability is essential.

6. Conclusions and next steps

Through this survey of published, peer-reviewed studies, we sought to document the current state of the research on the joint effects of genetic and environmental influences on alcohol consumption and related phenotypes in U.S. racial/ethnic minority population groups. Although the reviewed studies made important contributions to science, we identified additional advances that are warranted. First, and most generally, there is a need for an overall increase in the inclusion of more diverse U.S. populations. Our focus here was on African Americans, Latinos/Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians. Studies are especially needed that include Latino/Hispanic and American Indian samples, as well as studies including adults from a range of age groups to coincide with key developmental periods for alcohol use initiation and escalation in different racial/ethnic groups. While important, we do recognize that it may not always be possible to compare differences in G–E relationships across racial/ethnic groups, because the frequency of alleles at specific markers, the associations between alleles, and the distribution of exposure to specific environmental conditions can be different by population group. Regardless, it is important to recognize and address the relevant ethical and cultural issues that will emerge in this effort to be more inclusive and to provide equal access to this area of research (a topic covered by other articles in this special issue). Second, methodological advancements will strengthen our confidence in study findings, including larger sample sizes, greater consistency in phenotypic measures to facilitate meta-analysis, and careful selection of genetic effects and rigorous testing of G–E relationships5,50–52. Third, we focused on selection of environmental factors that have both theoretical and empirical precedent for inclusion in the study of G–E relationships. This revealed a relative dearth of studies that examined higher-order social control and trigger mechanisms, e.g., at the community- and societal-levels, which have broadly been shown to influence racial/ethnic differences in a variety of health outcomes. New investigations need to consider the challenge of how to more accurately capture and reflect the role of the environment in using a multi-level and longitudinal framework, as suggested by Boardman et al.8, and to conceptualize the mechanisms through which these influences shape GxE interactions8,10–12. We proposed a number of community and societal variables (under both social control and triggering mechanisms) that are associated with alcohol use behaviors in U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups as potential environmental indicators to study alongside genetic effects. It will be an important next step, as has been recommended for phenotypic measures, that we test and identify a core of validated and standardized environmental measures for use in studies of G–E relationships.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (K.C., K01AA021145; and K.K., P50AA022537, R37AA011408, R01AA023534).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Zemore SE, Mulia N, Jones-Webb R, Bond J, Greenfield TK. Neighborhood disadvantage and adult alcohol outcomes: differential risk by race and gender. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(6):865–873. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zapolski TC, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, Smith GT. Less drinking, yet more problems: Understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological bulletin. 2014;140(1):188. doi: 10.1037/a0032113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zemore SE, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Keithly S, Mulia N. Racial prejudice and unfair treatment: interactive effects with poverty and foreign nativity on problem drinking. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2011;72(3):361–370. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendler KS, Eaves LJ. Models for the joint effect of genotype and environment on liability to psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(3):279–289. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dick DM, Agrawal A, Keller MC, et al. Candidate gene–environment interaction research reflections and recommendations. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(1):37–59. doi: 10.1177/1745691614556682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan LE, Keller MC. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boardman JD, Daw J, Freese J. Defining the environment in gene–environment research: Lessons from social epidemiology. American journal of public health. 2013;103(S1):S64–S72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galea S, Ahern J, Vlahov D. Contextual determinants of drug use risk behavior: a theoretic framework. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80(3):iii50–iii58. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dick DM, Kendler KS. The impact of gene-environment interaction on alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res. 2012;34(3):318–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanahan MJ, Hofer SM. Social context in gene-environment interactions: retrospect and prospect. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2005;60(Spec No 1):65–76. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sher KJ, Dick DM, Crabbe JC, Hutchison KE, O’Malley SS, Heath AC. Review: Consilient research approaches in studying gene× environment interactions in alcohol research. Addiction biology. 2010;15(2):200–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higuchi S, Matsushita S, Imazeki H, Kinoshita T, Takagi S, Kono H. Aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes in Japanese alcoholics. The Lancet. 1994;343(8899):741–742. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91629-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age-period-cohort modelling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction. 2009;104(1):27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Ye Y, Bond J, Rehm J. Are the 1976–1985 birth cohorts heavier drinkers? Age-period-cohort analyses of the National Alcohol Surveys 1979–2010. Addiction. 2013;108(6):1038–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendler K, Gardner C, Dick D. Predicting alcohol consumption in adolescence from alcohol-specific and general externalizing genetic risk factors, key environmental exposures and their interaction. Psychological medicine. 2011;41(07):1507–1516. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000190X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dick DM, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. Exploring gene–environment interactions: Socioregional moderation of alcohol use. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2001;110(4):625. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Genes, environment, and psychopathology: Understanding the causes of psychiatric and substance use disorders. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2006. Genetic Control of Sensitivity to the Environment; pp. 291–319. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldron M, D’Onofrio B, Gottesman II. Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychological science. 2003;14(6):623–628. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyers JL, Shmulewitz D, Wall MM, et al. Childhood adversity moderates the effect of ADH1B on risk for alcohol-related phenotypes in Jewish Israeli drinkers. Addict Biol. 2015;20(1):205–214. doi: 10.1111/adb.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sartor CE, Wang Z, Xu K, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J. The Joint Effects of ADH1B Variants and Childhood Adversity on Alcohol Related Phenotypes in African-American and European-American Women and Men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(12):2907–2914. doi: 10.1111/acer.12572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lown EA, Nayak MB, Korcha RA, Greenfield TK. Child physical and sexual abuse: a comprehensive look at alcohol consumption patterns, consequences, and dependence from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(2):317–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caetano R, Field CA, Nelson S. Association between childhood physical abuse, exposure to parental violence, and alcohol problems in adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(3):240–257. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Childhood experiences and risk for psychopathology. In: Kendler KS, Prescott CA, editors. Genes, environment, and psychopathology: Understanding the causes of psychiatric and substance use disorders. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2006. pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Areas of disadvantage: a systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30(1):84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beach SR, Brody GH, Lei M-K, Philibert RA. Differential susceptibility to parenting among African American youths: testing the DRD4 hypothesis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(5):513. doi: 10.1037/a0020835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brody GH, Beach SR, Philibert RA, Chen Yf, Murry VM. Prevention effects moderate the association of 5-HTTLPR and youth risk behavior initiation: Gene× environment hypotheses tested via a randomized prevention design. Child development. 2009;80(3):645–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brody GH, Chen Yf, Beach SR. Differential susceptibility to prevention: GABAergic, dopaminergic, and multilocus effects. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2013;54(8):863–871. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brody GH, Yu T, Beach SR. A differential susceptibility analysis reveals the “who and how” about adolescents’ responses to preventive interventions: Tests of first-and second-generation Gene× Intervention hypotheses. Development and psychopathology. 2015;27(01):37–49. doi: 10.1017/S095457941400128X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brody GH, Beach SR, Philibert RA, et al. Parenting moderates a genetic vulnerability factor in longitudinal increases in youths’ substance use. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2009;77(1):1. doi: 10.1037/a0012996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enoch M-A, Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Shen P-H, Goldman D, Roy A. The influence of GABRA2, childhood trauma, and their interaction on alcohol, heroin, and cocaine dependence. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goyal N, Aliev F, Latendresse SJ, et al. Genes involved in stress response and alcohol use among high-risk African American youth. Substance abuse. 2015 doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1134756. just-accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kranzler HR, Scott D, Tennen H, et al. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism moderates the effect of stressful life events on drinking behavior in college students of African descent. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2012;159(5):484–490. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bujarski S, Lau AS, Lee SS, Ray LA. Genetic and environmental predictors of alcohol use in Asian American young adults. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2015;76(5):690–699. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irons DE, Iacono WG, Oetting WS, McGue M. Developmental trajectory and environmental moderation of the effect of ALDH2 polymorphism on alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(11):1882–1891. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irons DE, McGue M, Iacono WG, Oetting WS. Mendelian randomization: A novel test of the gateway hypothesis and models of gene–environment interplay. Development and psychopathology. 2007;19(04):1181–1195. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luczak SE, Corbett K, Oh C, Carr LG, Wall TL. Religious influences on heavy episodic drinking in Chinese-American and Korean-American college students. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2003;64(4):467–471. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendershot CS, MacPherson L, Myers MG, Carr LG, Wall TL. Psychosocial, cultural and genetic influences on alcohol use in Asian American youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(2):185–195. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du Y, Wan YJY. The interaction of reward genes with environmental factors in contribution to alcoholism in Mexican Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(12):2103–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enoch MA, Waheed JF, Harris CR, Albaugh B, Goldman D. Sex differences in the influence of COMT Val158Met on alcoholism and smoking in plains American Indians. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(3):399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ducci F, Enoch M, Hodgkinson C, et al. Interaction between a functional MAOA locus and childhood sexual abuse predicts alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder in adult women. Molecular psychiatry. 2008;13(3):334–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luczak SE, Wall TL, Cook TA, Shea SH, Carr LG. ALDH2 status and conduct disorder mediate the relationship between ethnicity and alcohol dependence in Chinese, Korean, and White American college students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(2):271. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaske J, Beaver KM, Wright JP, Boisvert D, Schnupp R. An interaction between DAT1 and having an alcoholic father predicts serious alcohol problems in a sample of males. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;104(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olfson E, Edenberg HJ, Nurnberger J, et al. An ADH1B Variant and Peer Drinking in Progression to Adolescent Drinking Milestones: Evidence of a Gene-by-Environment Interaction. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(10):2541–2549. doi: 10.1111/acer.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chartier KG, Dick DM, Almasy LA, et al. Interactions between alochol metabolism genes and religious involvement in association with maximum drinks and alcohol dependence symptoms. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2016;77(3):393–404. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dick DM, Agrawal A, Schuckit MA, et al. Marital status, alcohol dependence, and GABRA2: evidence for gene-environment correlation and interaction. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2006;67(2):185–194. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaufman J, Yang B-Z, Douglas-Palumberi H, et al. Genetic and environmental predictors of early alcohol use. Biological psychiatry. 2007;61(11):1228–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daw J, Shanahan M, Harris KM, Smolen A, Haberstick B, Boardman JD. Genetic sensitivity to peer behaviors: 5HTTLPR, smoking, and alcohol consumption. J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(1):92–108. doi: 10.1177/0022146512468591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lieberman R, Armeli S, Scott DM, Kranzler HR, Tennen H, Covault J. FKBP5 genotype interacts with early life trauma to predict heavy drinking in college students. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Eaves LJ. Genotype × Environment interaction in psychopathology: fact or artifact? Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1375/183242706776403073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Interpretation of interactions: guide for the perplexed. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):170–171. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agrawal A, Verweij K, Gillespie N, et al. The genetics of addiction—a translational perspective. Translational psychiatry. 2012;2(7):e140. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hurley TD, Edenberg HJ. Genes encoding enzymes involved in ethanol metabolism. Alcohol Res. 2012;34(3):339–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hines LA, Morley KI, Mackie C, Lynskey M. Genetic and environmental interplay in adolescent substance use disorders. Current addiction reports. 2015;2(2):122–129. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salvatore JE, Aliev F, Edwards AC, et al. Polygenic scores predict alcohol problems in an independent sample and show moderation by the environment. Genes. 2014;5(2):330–346. doi: 10.3390/genes5020330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mrug S, Windle M. DRD4 and susceptibility to peer influence on alcohol use from adolescence to adulthood. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2014;145:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luczak SE, Wall TL, Shea SH, Byun SM, Carr LG. Binge drinking in Chinese, Korean, and White college students: genetic and ethnic group differences. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(4):306–309. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Latvala A, Dick DM, Tuulio-Henriksson A, et al. Genetic correlation and gene-environment interaction between alcohol problems and educational level in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(2):210–220. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Penman-Aguilar A, Talih M, Huang D, Moonesinghe R, Bouye K, Beckles G. Measurement of Health Disparities, Health Inequities, and Social Determinants of Health to Support the Advancement of Health Equity. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 1):S33–42. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M. Strategy for investigating interactions between measured genes and measured environments. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(5):473–481. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760–773. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seo D, Sinha R. Neuroplasticity and predictors of alcohol recovery. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2015;37(1):143–152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: A natural experiment. Jama. 2003;290(15):2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trucco EM, Colder CR, Wieczorek WF, Lengua LJ, Hawk LW. Early adolescent alcohol use in context: How neighborhoods, parents, and peers impact youth. Development and psychopathology. 2014;26(02):425–436. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Academy of Medical Sciences Working Group. Identifying the Environmental Causes of Disease: How Should We Decide What to Believe and When to Take Action? Academy of Medical Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buu A, Mansour M, Wang J, Refior SK, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Alcoholism effects on social migration and neighborhood effects on alcoholism over the course of 12 years. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(9):1545–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turner RJ. Lifetime Cumulative Adversity and Drug Dependence: Racial/ethnic contrasts. Paper presented at: Bridging Science and Culture to Improve Drug Abuse Research in Minority Communities; September 24–26, 2001; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wallace JM., Jr The power of faith as a protective factor against drug abuse. Paper presented at: Bridging Science and Culture to Improve Drug Abuse Research in Minority Communities; 2001; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herd D. The influence of religious affiliation on sociocultural predictors of drinking among black and white Americans. Substance Use and Misuse. 1996;31(1):35–63. doi: 10.3109/10826089609045797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in alcohol consumption patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1995. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(6):659–668. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Michalak L, Trocki K, Bond J. Religion and alcohol in the U.S. National Alcohol Survey: how important is religion for abstention and drinking? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87(2–3):268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Muthén BO, Muthén LK. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U.S. national sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(2):290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Orcutt JD, Schwabe AM. Gender, race/ethnicity, and deviant drinking: A longitudinal application of social structure and social learning theory. Sociological Spectrum. 2012;32:20–36. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Herd D. The effects of parental influences and respondents’ norms and attitudes on black and white adult drinking patterns. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6(2):137–154. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cook WK, Mulia N, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Ethnic drinking cultures and alcohol use among Asian American adults: findings from a national survey. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47(3):340–348. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zemore SE. Acculturation and alcohol among Latino adults in the United States: a comprehensive review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(12):1968–1990. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park S-Y, Anastas J, Shibusawa T, Nguyen D. The impact of acculturation and acculturative stress on alcohol use across Asian immigrant subgroups. Substance use & misuse. 2014;49(8):922–931. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.855232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Herd D, Grube JW. Black identity and drinking in the US: a national study. Addiction. 1996;91(6):845–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.91684510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Adams GW. Discrimination, historical loss and enculturation: culturally specific risk and resiliency factors for alcohol abuse among American Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(4):409–418. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones-Webb RJ, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Neighborhood disadvantage, high alcohol content beverage consumption, drinking norms, and consequences: a mediation analysis. Journal of Urban Health. 2013;90(4):667–684. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Molina KM, Alegría M, Chen C-N. Neighborhood context and substance use disorders: A comparative analysis of racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125S:S35–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nyaronga D, Greenfield TK, McDaniel PA. Drinking context and drinking problems among black, white and Hispanic men and women in the 1984, 1995 and 2005 U.S. National Alcohol Surveys. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2009;70(1):16–26. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bryden A, Roberts B, McKee M, Petticrew M. A systematic review of the influence on alcohol use of community level availablity and marketing of alcohol. Health & Place. 2012;18:349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Theall KP, Scribner R, Cohen D, et al. The neighborhood alcohol environment and alcohol-related morbidity. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44(5):491–499. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lambert SF, Brown TL, Phillips CM, Ialongo NS. The relationship between perceptions of neighborhood characteristics and substance use among urban African American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;34(3–4):205–218. doi: 10.1007/s10464-004-7415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kadushin C, Reber E, Saxe L, Livert D. The substance use system: social and neighborhood environments associated with substance use and misuse. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998;33(8):1681–1710. doi: 10.3109/10826089809058950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bradizza CM, Stasiewicz PR. Qualitative analysis of high-risk drug and alcohol use situations among severly mentally ill substance abusers. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(1):157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Branas CC, Elliott MR, Richmond TS, Culhane DP, Wiebe DJ. Alcohol consumption, alcohol outlets, and the risk of being assaulted with a gun. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(5):906–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: a review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(1):158–169. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Kyrpi K. Alcohol control policies and alcohol consumption by youth: a multi-national study. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1849–1855. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.LaVeist TA, Wallace JM., Jr Health risk and inequitable distribution of liquor stores in African American neighborhood. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51(4):613–617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McKee P, Jones-Webb R, Hannan P, Pham L. Malt liquor marketing in inner cities: The role of neighborhood racial composition. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2011;10:24–38. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2011.547793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Williams DR, Takeuchi DT, Adair RK. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorder among blacks and whites. Social Forces. 1992;71(1):179–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among black and white men: results from a national survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(1):61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kost KA, Smyth NJ. Two strikes against them? Exploring the influence of a history of poverty and growing up in an alcoholic family on alcohol problems and income. Journal of Social Service Research. 2002;28(4):23–52. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mossakowski KN. Is the duration of poverty and unemployment a risk factor for heavy drinking? Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67(6):947–955. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mulia N, Ye Y, Zemore SE, Greenfield TK. Social disadvantage, stress and alcohol use among black, Hispanic and white Americans: findings from the 2005 U.S. National Alcohol Survey. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2008;69(6):824–833. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Caldwell TM, Rodgers B, Clark CL, Jefferis BJMH, Stansfeld SA. Lifecourse socioeconomic predictors of midlife drinking patterns, problems and abstention: findings from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95(3):269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cellini SR, Signe-Mary M, Ratcliffe C. The dynamics of poverty in the United States: a review of data, methods, and findings. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2008;27(3):577–605. [Google Scholar]