Abstract

Background

Suicidal ideation (SI) is a serious issue affecting U.S. veterans, and those with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are at an especially high risk of SI. Guilt has been associated with both PTSD and SI and may therefore be an important link between these constructs.

Methods

The present study compared models of trauma-related guilt and used path analysis to examine the direct and indirect effects of PTSD and trauma-related guilt on SI among a sample of 988 veterans receiving outpatient PTSD treatment at a Veterans Affairs (VA) specialty clinic.

Results

Results showed that a model of trauma-related guilt including guilt-cognitions and global guilt (but not distress) provided the best model fit for the data. PTSD and trauma-related guilt had direct effects on SI, and PTSD exhibited indirect effects on SI via trauma-related guilt.

Limitations

The use of cross-sectional data limits the ability to make causal inferences. A treatment-seeking sample composed primarily of Vietnam veterans limits generalizability to other populations.

Conclusions

Trauma-related guilt, particularly guilt cognitions, may be an effective point of intervention to help reduce SI among veterans with PTSD. This is an important area of inquiry, and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: Guilt, emotions, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicide, suicidal ideation, veterans

Introduction

Suicidal ideation (SI) is a serious concern among veterans. According to the National Health and Resilience Veterans Study, 13.7% of a nationally-representative sample of U.S. veterans reported current SI during at least one of two time points in 2011 and 2013 (Smith et al., 2016). Veterans also experience high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Across population-based samples of veterans from various military eras, prevalence estimates of current PTSD have ranged from 12 to 15% (Kang et al., 2003; Kulka et al., 1990, Tanielian et al., 2008). Veterans with PTSD are at especially high risk of suicidal behavior, including higher rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and deaths by suicide compared to veterans without PTSD (see Panagioti, Gooding, & Tarrier, 2009 and Pompili et al., 2013 for reviews). In one study, veterans with PTSD were four times more likely to have SI than veterans without PTSD (Jakupcak et al., 2009). Given the high rates and co-occurrence of SI and PTSD among veterans, it is essential to identify relevant constructs that may underlie this relationship. Guilt is a potentially important construct that is associated with both PTSD and SI and may link these variables.

Guilt is a self-conscious negative emotion composed of cognitive and affective experiences (Kubany et al., 1995; Kubany & Watson, 2003). Guilt has been associated with PTSD (see Pugh et al., 2015 for a review) and is now explicitly included in the diagnostic criteria for PTSD (i.e., distorted cognitions about the cause of the event and/or persistent negative mood that can include guilt; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Although results have been mixed, multiple cross-sectional studies have shown positive associations between guilt and PTSD.

Guilt has also been associated with increased risk for suicidal behavior. In a study of Vietnam veterans, combat-related guilt was the strongest predictor of suicidal thoughts and attempts (Hendin & Hass, 1991). Bryan and colleagues (2013) found that guilt-proneness was higher among active duty military personnel with a history of SI. Guilt was also associated with more severe current SI, even after controlling for PTSD and depression symptoms (Bryan et al., 2013).

Given that guilt is associated with both PTSD and SI, it may be a potential mediator of the relationship between PTSD and SI. Initial evidence supports this hypothesis. Results from Bryan et al. (2013) suggested that guilt and shame together mediated the relationship between PTSD and SI, and further research showed that guilt partially mediated the relationship between PTSD and SI (Bryan et al., 2015). A recent study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans also showed that trauma-related guilt mediated the relationship between PTSD symptoms and SI (Tripp & McDevitt-Murphy, 2016).

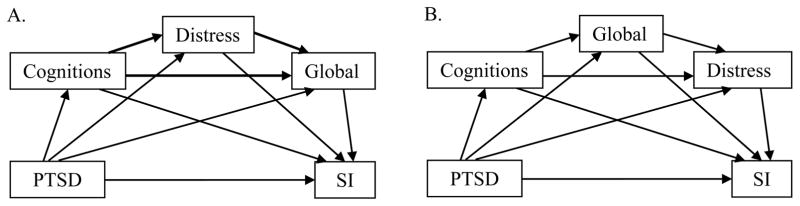

Currently, the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI; Kubany et al., 1996) is the only validated measure of trauma-related guilt, which is guilt resulting from a specific event. Kubany and colleagues (Kubany et al., 1995; Kubany et al., 1996; Kubany & Watson, 2003) designed the TRGI with two subscales to capture the combined presence of negative affect (distress) and guilt-specific beliefs (guilt cognitions), as well as a third subscale to measure the overall intensity of trauma-related guilt (global guilt). Figure 1A depicts Kubany’s model of trauma-related guilt. Brown and colleagues (2015) recently evaluated Kubany and Watson’s (2003) model of trauma-related guilt as a predictor of PTSD and depression symptoms. They found that guilt cognitions and distress had direct effects on PTSD and depressive symptoms, whereas global guilt did not. Tripp and McDevitt-Murphy (2016) tested the TRGI subscales as serial mediators of the relationship between PTSD and SI (refer to Figure 1A) and reported indirect effects of PTSD on SI via pathways through 1) guilt cognitions and global guilt, 2) distress and global guilt, and 3) the full model with all three subscales. These findings provided support for the existing model (i.e., Kubany & Watson, 2003) and evidence that trauma-related guilt may partially explain the relationship between PTSD symptoms and SI. However, studies examining model fit and comparing alternative models of the TRGI subscales are still needed to identify the relative importance of guilt dimensions to trauma-related outcomes, including SI.

Figure 1.

Conceptual models of trauma-related guilt. A. Model 1: TRGI model of trauma-related guilt, bold lines indicate pathways specified by Kubany and Watson (2003); B. Model 2: Alternate model prioritizing guilt-specific TRGI subscales over distress.

Although the TRGI has proven useful, the content of the distress subscale has raised concern (e.g., Browne et al., 2015). The distress subscale measures undifferentiated emotional distress related to trauma, e.g., “What happened causes me emotional pain” (Kubany et al., 1995; Kubany et al., 1996). This subscale was intended to capture diffuse negative affect (Kubany et al., 1996), which is a higher order dimension associated with multiple discrete emotions (Watson & Tellegen, 1985). As such, the distress subscale is not guilt-specific and captures distress related to any negative emotion (e.g., fear, anger, sadness). In contrast, the guilt cognitions subscale captures guilt-specific attributions made about the event, e.g., “I was responsible for causing what happened.” Likewise, the global guilt subscale measures the self-reported magnitude and intensity of trauma-related guilt. Together, the guilt cognitions and global guilt subscales may sufficiently capture the cognitive and affective components specific to trauma-related guilt. Removing the distress subscale from the model may provide an equally adequate, or even superior, measure of trauma-related guilt. Model comparison examining the TRGI subscales in variant order would help us better understand trauma-related guilt and its potential role in posttraumatic outcomes. This is especially relevant in light of emerging evidence suggesting that trauma-related guilt may be an important mechanism by which PTSD confers risk for SI. Additional research is needed to better understand these intricate relationships.

Present Study

The aim of the present study was to examine trauma-related guilt in relationship to PTSD and SI. We tested and compared three models of trauma-related guilt in order to determine which best fit the data: Kubany and Watson’s (2003) model (Model 1; Figure 1A), a model that de-emphasized distress by placing it last in the serial mediation (Model 2; Figure 1B), and a model without distress (Model 3; Figure 2). We then used the best-fitting model to examine the direct and indirect effects of PTSD symptom severity and trauma-related guilt on SI. We hypothesized the following: 1) the model without the distress subscale (Model 3) would provide the best fit to the data; 2) PTSD symptoms and trauma-related guilt would be positively associated with SI; and 3) trauma-related guilt would partially mediate the relationship between PTSD and SI, such that the mediating effect of trauma-related guilt would explain a significant portion of the effect of PTSD on SI.

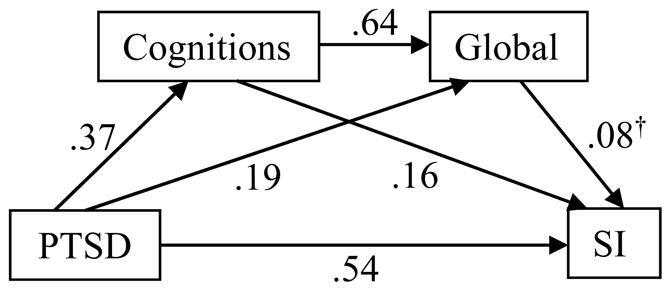

Figure 2.

Standardized direct effects among variables in Model 3. All values p < .001, except †p < .05.

Methods

Participants & Procedure

We analyzed archival data from 988 veterans receiving care at an outpatient Veterans Affairs (VA) specialty PTSD clinic between 1996 and 2000. Of the 1,000 veterans who completed questionnaires on the variables of interest, twelve were dropped from the present analyses due to incomplete data. As part of a standard initial evaluation for the PTSD clinic, participants completed clinical interviews and a battery of self-report questionnaires. PTSD diagnosis was based on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995). A small portion of the present sample (n = 112, 11.34%) were administered an abbreviated CAPS by an experienced PTSD clinician using the original F1/I2 decision rule (frequency ≥ 1 and intensity ≥ 2; Weathers et al., 2001) to judge symptoms as present or absent for the purpose of determining diagnosis. Use of these data for research purposes was approved by the institutional review board.

Measures

Demographic Information

Demographic information collected included age, gender, race, and marital status.

PTSD symptom severity

The Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD; Keane et al., 1988) is a 35-item self-report measure that assesses DSM-III symptoms of PTSD in veteran populations. Participants respond to items using a 5-point Likert scale on which 1 = Not at all true and 5 = Extremely true. Responses are summed to provide an overall score of PTSD symptom severity. This measure has demonstrated strong internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and sensitivity distinguishing between veterans with and without PTSD. For the present analyses, the two items assessing suicidal ideation were not included in the M-PTSD total score, because these items were used as the outcome variable. Also, the single item reflecting guilt was removed due to overlap with the mediation variables. Internal consistency in the present sample was good, Cronbach’s α = .83.

Suicidal Ideation

Two items from the M-PTSD (Keane et al., 1986) were used to measure SI. The use of face valid items extracted from existing measures is consistent with previous research practice and has generally shown reliability with measures of suicidal ideation (Desseilles et al., 2012). The items (“When I think of the things that I did in the military, I wish I were dead” and “Lately, I have felt like killing myself”) were rated on a Likert scale from 1 = Not at all true to 5 = Extremely true. The scores for these two items were summed to reflect the degree to which each participant endorsed SI. These two items exhibited good internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = .76.

Trauma-related guilt

The Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI; Kubany et al., 1996) is a 32-item self-report measure composed of three subscales: Guilt cognitions (22 items; e.g., “What I did was unforgivable”), distress (6 items; e.g., “I experience severe emotional distress when I think about what happened”), and global guilt (4 items; e.g., “I experience intense guilt that relates to what happened”). Respondents rate each statement using a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the degree to which they believe the statement is true about themselves (i.e., Extremely True, Very True, Somewhat True, Slightly True, or Never True). In the present sample, each subscale exhibited good internal consistency. Cronbach’s α was .91 for guilt cognitions, .87 for distress, and .88 for global guilt.

Data Analyses

Univariate statistics and bivariate relationships among variables were examined prior to hypothesis testing. Path analysis (SAS PROC CALIS) with model trimming procedure was used to compare models of trauma-related guilt as a mediator between PTSD symptoms and SI. Because all possible pathways between variables were specified in each initial model, we iteratively removed non-contributing pathways. Specifically, we dropped statistically non-significant paths and used chi-squares difference testing to determine the most parsimonious version of each model without significantly detracting from model fit. After we achieved the most parsimonious version of each model, we compared model fit between models using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwartz, 1978). In using BIC to compare models, a 10-point difference can be interpreted as “very strong” evidence (i.e., p < .05) of the superiority of the model with the smaller BIC (Kass & Raftery, 1995; Raftery, 1995). A difference of six to nine points may be interpreted as “strong” support for a meaningful difference between the models. Once the best-fitting model was determined, we examined indirect effects using 5,000 bootstrap samples to examine the serial mediation effects of trauma-related guilt on the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and SI. Resampling offers an advantage over conventional tests, such as Sobel’s z, because it takes into account the positive skew inherent to indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). As such, bootstrapping methods are more powerful than conventional tests, with mediation deemed significant when the resulting 95% confidence interval (CI) does not span 0.

Results

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Univariate statistics and bivariate relationships are presented in Table 2. All variables were significantly correlated with one another. The TRGI model of trauma-related guilt (Model 1; Figure 1A) was fully saturated. Two of the paths (distress→SI and PTSD→global guilt) were non-significant. Excising these from the model did not diminish model fit, ΔX2(2) = 3.19, p = .20. Model 2 (Figure 1B) tested the TRGI subscales in a variant order, entering guilt cognitions and global guilt prior to distress in the model. The first iteration with all three subscales was fully saturated. Two of the paths (guilt cognitions→distress and distress→SI) were non-significant. Excising these paths from the model did not diminish model fit, ΔX2(2) = 0.95, p = .62.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variable (N = 988)

|

n

|

%

|

|---|---|---|

| Age: M = 50, SD = 9.74 | ||

| Gender | ||

| Men | 967 | 97.9 |

| Women | 21 | 2.1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 573 | 58.2 |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 333 | 33.8 |

| Never Married | 79 | 8.0 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 559 | 56.6 |

| Caucasian American | 403 | 40.8 |

| Native American | 15 | 1.5 |

| Unknown | 10 | 1.0 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 9 | 1.0 |

| Current Mental Health Diagnosesa | ||

| PTSD | 912 | 92.3 |

| Subclinical PTSD | 27 | 3.4 |

| Depression | 689 | 51.5 |

| M-PTSD above 107b | 773 | 78.2 |

| Trauma-related Guiltc | ||

| Guilt Cognitions | 982 | 99.4 |

| Guilt Distress | 978 | 98.9 |

| Global Guilt | 935 | 94.6 |

| Suicidal Ideationc | 692 | 70.0 |

Diagnoses based on structured clinical interview;

Standard cutoff score for probable PTSD;

Endorsed any level of variable > 0.

Table 2.

Univariate statistics

| M(SD) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| 1. PTSD | 99.83(14.38) | 45.44–145 | ||||

| 2. Guilt cognitions | 1.71(0.09) | 0–3.91 | .37 | |||

| 3. Distress | 2.99(0.87) | 0–4 | .54 | .46 | ||

| 4. Global guilt | 2.33(1.13) | 0–4 | .43 | .71 | .63 | |

| 5. SI | 4.40(2.28) | 2–10 | .63 | .41 | .40 | .42 |

All correlations significant at p < .001

Supported by the finding that distress was not directly associated with SI in either model and did not exhibit indirect effects in the second model, we tested Model 3, which excluded distress entirely (Figure 2). Examination of the BICs suggested that Model 3 without distress explained the same amount of variance in SI (R2 = .44), while providing a much better fit to the data (BIC = 68.96) than did Models 1 or 2 (BIC = 92.83 and 90.59, respectively). Direct effects for Model 3 are depicted in Figure 2.

Given the significant pathways between PTSD and the mediators and between the mediators and SI in Model 3, we next used bootstrapping to examine indirect effects. PTSD exhibited significant direct effects on SI, as well as on guilt cognitions and global guilt. Guilt cognitions and global guilt also had direct effects on SI. PTSD had indirect effects on SI via guilt cognitions and global guilt. An indirect effect of PTSD on global guilt via guilt cognitions was also observed. Table 3 presents the standardized effects and 95% CIs for direct and indirect effects of the bootstrapped mediation analyses.

Table 3.

Direct and indirect effects for mediation pathways

| Direct β(95% CI)

|

Indirect β(95% CI)

|

%

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD→SI | .54(.08, .23) | .09(.07, .12)† | 14 |

| PTSD→Cog→SI | .06(.03, .09) | 10 | |

| PTSD→Global→SI | .02(.0004, .03) | 3 | |

| PTSD→Cog→Global→SI | .02(.0006, .04) | 3 | |

| PTSD→Cog→Global | .19(.14, .25) | .24(.20, .28) | 56 |

| Cog→Global→SI | .16(.08, .23) | .05(.003, .10) | 24 |

% = Portion of total effect (direct + indirect effects) of independent variable on dependent variable explained by the indirect path via the mediator(s).

Total indirect effect of PTSD on SI via guilt subscales.

Discussion

The results of the present study provided support for a model of trauma-related guilt composed of guilt-related cognitions and global guilt. In a model of PTSD and trauma-related guilt predicting SI, removal of the distress subscale led to better model fit while explaining the same amount of variance as did the models with distress. It appears that in the context of PTSD and SI, guilt cognitions and global guilt created an adequate and parsimonious measure of trauma-related guilt. These results are consistent with the fact that the distress subscale captures diffuse emotional distress and is not guilt-specific.

Using this more parsimonious model, we found that PTSD, guilt cognitions, and global guilt each had direct effects on SI. Additionally, we found that the guilt cognitions and global guilt subscales partially mediated the relationship between PTSD and SI. The mediating effect of these subscales supports trauma-related guilt as an important construct that may partially explain the relationship between PTSD and SI. This finding highlights the important role that trauma-related guilt plays between PTSD and SI. Trauma-related guilt, specifically guilt-cognitions, may be a useful clinical indicator of SI risk, as well as a point of intervention for reducing SI among veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with existing PTSD treatment literature. There is evidence that some trauma-focused treatments (e.g., Cognitive Processing Therapy; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2017) that directly target erroneous guilt cognitions effectively reduce both trauma-related guilt (e.g., Dondanville et al., 2016) and suicidal ideation (Bryan et al., 2016).

A number of limitations of the present study should be noted. We used archival cross-sectional data, which limits the ability to infer causal relationships between variables. Data are based on self-report, and the results should be interpreted in light of this limitation. Additionally, the sample was primarily male Vietnam veterans; therefore, it is unknown whether the results may generalize to other populations, including female veterans, other era veterans, or civilians. For example, combat trauma is prevalent in VA settings; whereas, community samples may exhibit higher rates of other trauma types, such as sexual violence. Finally, the M-PTSD does not reflect current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Despite these limitations, the study exhibited several important strengths. The sample is representative of veterans seeking PTSD treatment within the VA system and therefore generalizable to this important population. The large sample size provided sufficient power for contemporary model comparison and path analysis. Furthermore, this is the first study to compare different models of trauma-related guilt using the TRGI (Kubany et al., 1996).

Continued research is needed to build on the results of this study and further examine the model of trauma-related guilt without distress in relationship to PTSD, SI, and other negative outcomes. Moral injury may be one such outcome (see Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016 for a review). Moral injury is a syndrome characterized by emotional responses of guilt and shame following perceived violation of moral values. Moral injury has been related to myriad social and functional difficulties, including SI (Bryan et al., 2014). Research is needed to better understand the relationship between trauma-related guilt and moral injury. It is possible that moral injury may lead to higher levels of trauma-related guilt and/or SI. Further research is needed to evaluate how the relationship between guilt and SI functions within the context of moral injury. Additionally, comparison of the role of trauma-related guilt between individuals with and without moral injury would provide unique insight into potential treatment approaches. Research is also needed to better understand how guilt and shame co-occur and potentially interact with each other and differentially contribute to posttraumatic outcomes. Future research is needed to assess whether the relationships between variables observed in the present study hold across diverse samples and settings. Future research should examine trauma-related guilt among different groups of veterans, including women veterans and veterans of other eras. Examining differences in levels of trauma-related guilt between veterans who experience SI and those who do not may further enhance our understanding of the association between these variables, as well. Comparison of differences between men and women and between civilians and veterans is also needed. Overall, the results of the present study support the importance of further investigation of trauma-related guilt, particularly as it relates to critical trauma-related outcomes, including SI.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Author; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne KC, Trim RS, Myers US, Norman SB. Trauma-related guilt: Conceptual development and relationship with posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:134–141. doi: 10.1002/jts.21999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Bryan C, Morrow C, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud B. Moral injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in a military sample. Traumatology. 2014;20:154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, Hernandez AM, Mintz J, Peterson AL, Yarvis JS, Resick PA the STRONG STAR Consortium. Evaluating potential iatrogenic suicide risk in trauma-focused group cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of PTSD in active duty military personnel. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:549–557. doi: 10.1002/da.22456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud B. Guilt, shame, and suicidal ideation in a military outpatient clinical sample. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:55–60. doi: 10.1002/da.22002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Roberge E, Bryan AO, Ray-Sanneurud B, Morrow CE, Etienne N. Guilt as a mediator of the relationship between depression and posttraumatic stress with suicide ideation in two samples of military personnel and veterans. Int J Cogn Ther. 2015;8:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Desseilles M, Perroud N, Guillaume S, Jaussent I, Genty C, Malafousse A, Courtet P. Is it valid to measure suicidal ideation by depression rating scales? J Affect Disord. 2012;136:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondanville KA, Blankenship AE, Molino A, Resick PA, Wachen JS, Mintz J, … Young-McCaughan S. Qualitative examination of cognitive change during PTSD treatment for active duty service members. Behav Res Ther. 2016;79:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt S, Frazier P. A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Mil Psychol. 2016;28:318–330. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. Evolution, attractiveness, and the emergence of shame and guilt in a self-aware mind: A reflection on Tracy and Robins. Psychol Inq. 2004;15:132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hendin H, Haas AP. Suicide and guilt as manifestations of PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(5):586–591. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.5.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Cook J, Imel Z, Fontana A, Rosenheck R, McFall M. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(4):303–306. doi: 10.1002/jts.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HK, Natelson BH, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Murphy FM. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome-like illness among Gulf War Veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 Veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141–148. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Caddell JM, Taylor KL. Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Three studies in reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:85–90. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Abueg FR, Owens JA, Brennan JM, Kaplan AS, Watson SB. Initial examination of a multidimensional model of trauma-related guilt: Applications to combat veterans and battered women. J Psychopathol Behav. 1995;17:353–376. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Abueg FR, Manke FP, Brennan JM, Stahura C. Development and validation of the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI) Psychol Assessment. 1996;8:428. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Watson SB. Guilt: Elaboration of a multidimensional model. Psychol Rec. 2003;53:51–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS. Trauma and the Vietnam war generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Brunner/Mazel; Philadelphia: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Øktedalen T, Hoffart A, Langkaas TF. Trauma-related shame and guilt as time-varying predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms during imagery exposure and imagery rescription – A randomized controlled trial. Psychother Res. 2015;25:518–532. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.917217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagioti M, Gooding P, Tarrier N. Post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal behavior: A narrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Sher L, Serafini G, Forte A, Innamorati M, Dominici G, … Girardi P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide risk among veterans: A literature review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:802–812. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a21458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh LR, Taylor PJ, Berry K. The role of guilt in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2015;182:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol Methodol. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand R, Acosta J, Burns RM, Jaycox LH, Pernin CG. The war within: Preventing suicide in the U.S. military. RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research; Santa Monica: 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual. New York: The Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Smith NB, Mota N, Tsai J, Monteith L, Harpaz-Rotem I, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Nature and determinants of suicidal ideation among US veterans: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. J Affect Disord. 2016;197:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing RL. Shame and guilt. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, Adamson DM, Brunam MA, Burns RM, Caldarone LB, … Yochelson MR. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. RAND Corporation; Santa Monica: 2008. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG720.html. [Google Scholar]

- Tripp JC, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Trauma-related guilt mediates the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1111/sltb.12266. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Tellegen A. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:219–235. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]