Abstract

Objective

The relationship between admission nutritional status and clinical outcomes following hospital discharge is not well established. This study investigated whether older patients’ nutritional status at admission predicts unplanned readmission or death in the very early or late periods following hospital discharge.

Design, setting and participants

The study prospectively recruited 297 patients ≥60 years old who were presenting to the General Medicine Department of a tertiary care hospital in Australia. Nutritional status was assessed at admission by using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) tool, and patients were classified as either nourished (PG-SGA class A) or malnourished (PG-SGA classes B and C). A multivariate logistic regression model was used to adjust for other covariates known to influence clinical outcomes and to determine whether malnutrition is a predictor for early (0–7 days) or late (8–180 days) readmission or death following discharge.

Outcome measures

The impact of nutritional status was measured on a combined endpoint of any readmission or death within 0–7 days and between 8 and 180 days following hospital discharge.

Results

Within 7 days following discharge, 29 (10.5%) patients had an unplanned readmission or death whereas an additional 124 (50.0%) patients reached this combined endpoint within 8–180 days postdischarge. Malnutrition was associated with a significantly higher risk of combined endpoint of readmissions or death both within 7 days (OR 4.57, 95% CI 1.69 to 12.37, P<0.001) and within 8–180 days (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.28, P=0.007) following discharge and this risk remained significant even after adjustment for other covariates.

Conclusions

Malnutrition in older patients at the time of hospital admission is a significant predictor of readmission or death both in the very early and in the late periods following hospital discharge. Nutritional state should be included in future risk prediction models.

Trial registration number

ACTRN No. 12614000833662; Post-results.

Keywords: geriatric medicine, quality in health care, general medicine (see internal medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The research was a large prospective observational study evaluating the association between nutritional status and readmission or death in medical inpatients ≥60 years old.

A dietitian used a comprehensive and valid nutritional assessment tool to confirm the malnutrition diagnosis.

Readmissions presenting to all other hospitals were captured.

The single-centre study included only older medical patients.

Introduction

Recent decades have witnessed a vast improvement in life expectancy, leading to an increasing number of older patients with multiple chronic problems. While the number of beds for acute patients has declined, unplanned hospital admissions have increased, particularly among the elderly.1 Older patients with multiple comorbid illnesses experience poor clinical outcomes after hospital discharge, including recurrent unplanned readmissions and mortality.2 Adverse outcomes following discharge may be indicative of unresolved acute illness, ongoing chronic illness and the development of new medical problems or gaps in outpatient care.3–5 Although adverse outcomes following discharge are not totally preventable, studies suggest that targeted intervention such as improved discharge planning with a focus on transitional care services may provide beneficial results.6

The likelihood of an unplanned admission is highest in the immediate postdischarge period.7 There may be advantages in predicting readmissions that occur shortly after discharge. However, most studies have only assessed readmission patterns within 30 days of discharge, and few studies have examined readmission patterns up to 180 days postdischarge.8 Graham and Marcantonio have suggested that different risk factors may be responsible for very early and late readmissions and that each type of readmission needs differently targeted interventions that can only be implemented in advance if predictive factors are identified.9

Readmission and mortality risk prediction is a complex endeavour and remains poorly understood. A recent meta-analysis of 26 readmission risk prediction models for medical patients tested in a variety of populations and settings was used for comparing different hospitals and the appropriate applications of transitional care services; the analysis found these models had a poor predictive ability and suggested a need for high-quality data sources that include clinically relevant variables.10 None of the studies included in this meta-analysis considered patients’ nutritional status during index admission as a determinant of readmissions.

Studies suggest that up to 30% of hospitalised patients may be malnourished at the time of admission and that malnutrition has a negative impact on convalescence and reduces resistance to future infections and diseases causing poor clinical outcomes.11–13 Older patients are at a high risk of malnutrition than others and reasons for poor nutritional status in this group are multifactorial and include physiological, social and psychological factors which affect food intake and weight and this is further exacerbated by underlying medical illness.14 Few studies have assessed the association between nutritional status at admission and clinical outcomes in the very early and the late periods following hospital discharge. Furthermore, most of these studies are retrospective, and the use of a comprehensive nutritional assessment tool, like the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA), to diagnose malnutrition is rare. Therefore, this study was designed to determine whether nutritional status at admission, as diagnosed by a qualified dietitian using PG-SGA, influences a combined clinical outcome of readmission or mortality within 7 days and between 8 and 180 days following hospital discharge and whether malnutrition could be used as one of the predictors of early and late readmissions and death.

Methods

Study design and population

This prospective cohort study, included patients ≥60 years of age admitted to the Department of General Medicine of a large tertiary care hospital in Australia (Flinders Medical Centre, 520 beds), between August 2014 and March 2016. The exclusion criteria were refusal or inability to give informed consent, patients referred to palliative care and non-English-speaking patients, who were excluded due to a lack of funds to hire an interpreter. The required sample size for this study, calculated on the basis of a previous study showing early readmission rate of 7.8%, was estimated at 569 patients, but insufficient resources led to the recruitment of only 297 patients.9

Outcomes

The study’s primary outcome was a combined endpoint of either the first unplanned readmission to any of the acute care hospitals in the state of South Australia or death, within 0–7 days and between 8 and 180 days after hospital discharge. In this study, unplanned readmission was defined as any unscheduled hospitalisation to any hospital in the state of South Australia that was not for a planned investigation (eg, elective endoscopy) or non-emergent treatment (eg, planned drug infusion). The primary endpoint of readmissions or deaths were recorded from a central computer database, which captures these events for all state hospitals.

Nutritional status assessment

After obtaining written informed consent from patients, it was ensured that nutrition screening with Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) had been performed. It is a standard policy in our hospital to screen all patients with MUST at the time of admission. MUST includes a body mass index score, a weight loss score and an acute disease score and classifies patients as low, moderate or high risk of malnutrition.15 Following this all participating patients were then referred to a qualified dietitian for confirmation of their nutritional status by PG-SGA. The PG-SGA16 generates a numerical score while also providing an overall global rating divided into three categories: well nourished (PG-SGA A), moderately malnourished or suspected of being malnourished (PG-SGA B) or severely malnourished (PG-SGA C). For each PG-SGA component, points (0–4) are awarded depending on the impact on nutritional status. Component scores are combined to obtain total scores that range from 0 to 35 with scores ≥7, indicating a critical need for nutritional intervention and symptom management.17 The three different dietitians who were involved in the assessment of nutritional status using the PG-SGA received training prior to the study’s commencement. The PG-SGA classes were divided into two categories by combining PG-SGA classes B and C into the malnourished category for easily interpreting patients as nourished (PG-SGA class A) and malnourished (PG-SGA classes B and C). Furthermore, PG-SGA scores were split into a categorical variable with a PG-SGA score of <7, indicative of no critical need for nutrition intervention and ≥7, indicating critical need for intervention.

Covariates

Several known variables that can influence outcomes after hospital discharge were recorded at the baseline. Sociodemographic data, number of hospitalisations during the 6 months before index admission (current hospital admission) and clinical information were recorded at the baseline. Comorbidity was assessed with the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the total number of medications were recorded at the time of admission. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the EuroQoL 5-Dimensions 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire, a simple, self-administered instrument which is able to distinguish between 3125 states of health.18 A UK-specific algorithm developed using time-trade-off techniques was used to convert the EQ-5D-5L health description into a valuation ranging from −0.281 to 1.19 A Visual Analogue Scale score, which provides an unweighted measure of HRQoL, can also be calculated from the questionnaire. The main diagnosis of index admission was retrieved from medical records and divided into seven categories according to the system affected: (1) respiratory disease, (2) cardiovascular disease, (3) neuropsychiatric disease, (4) gastrointestinal disease, (5) falls, (6) renal disease and (7) miscellaneous diseases, including infections. The index admission’s acuity was gauged from the total number of medical emergency response team calls and the number of hours spent in the intensive care unit (ICU). Length of hospital stay (LOS) was determined from the day of admission to the day of discharge. The study recorded any unplanned hospital presentations to any of the hospitals in South Australia within 0–7 days and between 8 and 180 days after hospital discharge, as well as any recorded deaths at the same time points, using the central hospital computer database.

Statistics

Demographic variables were assessed for normality using a skewness and kurtosis (sk) test. Data are presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR), and Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were applied as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency and per cent and compared using Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

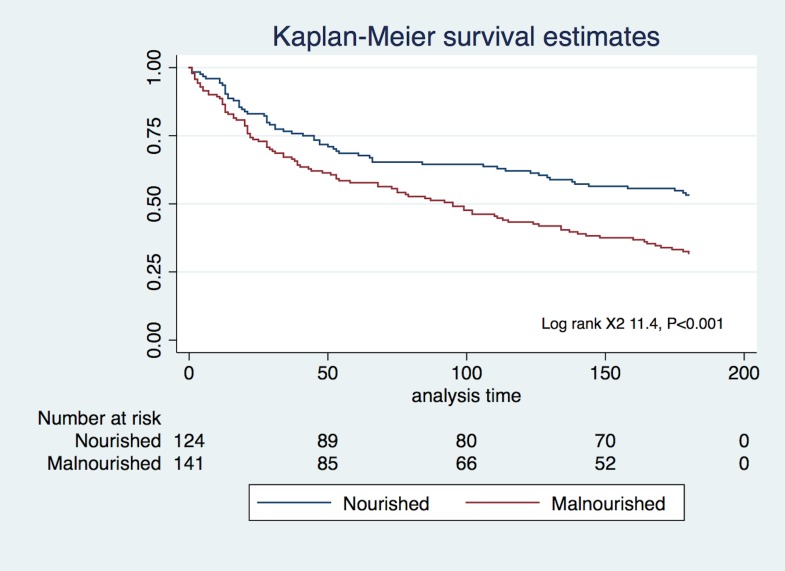

Univariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between nutritional status and the combined endpoint of unplanned readmission or death within 7 days and between 8 and 180 days postdischarge. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the relationship between readmission/death and nutrition status at admission was adjusted for other variables: age, gender, Charlson Comorbidity Index, principal diagnosis at presentation, number of medications at admission, LOS, number of medical emergency response team calls during index admission and total number of hours spent in the ICU. Variance inflation factor and tolerance values were used to detect collinearity between variables included in the model.20 A link test was used to confirm that the linear approach to model the outcome was correct. Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was plotted from time of discharge to the first onset of any of the primary outcomes to detect proportion of patients who did not experience the primary outcome. A log-rank test was used to compare survival proportions in the nourished and malnourished groups. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analysis was performed using STATA V.13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

This study recruited 297 patients, and nutrition status, as determined by PG-SGA, was available for 277 patients. Mean age was 80.3 years (SD 8.7, range 60–97) with 178 (64.3%) of the patients being women and the majority of patients came from home. There was no difference in the nutrition status between men and women (mean PG-SGA score 9.7 (SD 5.8) vs 9.2 (SD 5.3), P=0.44) in men and women, respectively) and the nutrition status of patients who came from a nursing home was similar to those who came from home (mean PG-SGA score 9.0 (SD 4.5) vs 9.4 (SD 5.6), P=0.70) in nursing home and patients from home, respectively). Patients had multiple comorbidities (mean number of comorbidities 6.2, SD 2.7, range 0–16), and the mean Charlson Comorbidity Index was 2.3 (SD 1.8). The median LOS for the index hospitalisation was 7 (IQR 3.4–14.6) days. Within 7 days after discharge, 29 (10.5%) patients had an unplanned readmission or death (primary endpoint). Among the 29 patients who had the primary endpoint within 7 days, 13 (44.8%) had been admitted prior to the index admission. The primary endpoint occurred in 124 (50.0%) patients within 8–180 days postdischarge and 69 (55.7%) of these patients had been admitted in the 6 months prior to the index admission. Patients who were malnourished at the time of index admission were significantly older (P=0.001), had lower quality of life (P=0.03) and stayed longer (P=0.02) in the hospital as compared with the nourished patients. Respiratory illness, miscellaneous diseases including sepsis and cardiovascular diseases were the three main diagnoses during index hospitalisation with 86 (28.9%), 67 (22.6%) and 55 (18.5%) cases, respectively.

Association of malnutrition with very early and late unplanned readmissions and mortality

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics according to the occurrence of combined endpoint of readmission or death within 0–7 days and 8–180 days of discharge, respectively. Malnutrition risk, as determined by the MUST score, and the classification of patients as being malnourished per PG-SGA class were significantly higher in subjects who developed the combined endpoint both within 0–7 days (83% vs 51%) and 8–180 (60% vs 43%) days postdischarge (P<0.05). Similarly, a significantly higher proportion of patients who were in critical need of nutrition therapy (as indicated by PG-SGA score of ≥7) at the time of index admission suffered the combined endpoint both within 0–7 days (P=0.002) and 8–180 days (P=0.02) following hospital discharge (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to primary endpoint (readmission/death) at 0–7 days and 8–180 days postdischarge

| Readmission/death within 0–7 days (n=29) |

No readmission/death within 0–7 days (n=248) |

P value | Readmission/death within 8–180 days (n=124) |

No readmission/death within 8–180 days (n=124) |

P value | |

| Age mean (SD) | 81.2 (7.6) | 80.2 (8.8) | 0.74 | 80.3 (8.6) | 80.0 (9.0) | 0.77 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 13 (44.8) | 165 (66.5) | 0.02 | 80 (64.5) | 85 (68.5) | 0.50 |

| Total comorbidities, mean (SD) | 6.8 (3.0) | 6.1 (2.7) | 0.20 | 6.6 (2.9) | 5.7 (2.5) | 0.012 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.1) | 2.2 (1.8) | 0.09 | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.1 (1.8) | 0.16 |

| Total medications, mean (SD) | 9.1 (4.5) | 9.6 (4.4) | 0.56 | 10.3 (4.5) | 8.9 (4.2) | 0.007 |

| Principal diagnosis at index admission, n (%) | ||||||

| Respiratory | 13 (44.8) | 72 (29.0) | 0.34 | 33 (26.6) | 39 (31.5) | 0.02 |

| CVS | 6 (20.7) | 44 (17.7) | 28 (22.6) | 16 (12.9) | ||

| Neuropsychiatric | 2 (6.9) | 23 (9.3) | 11 (8.9) | 12 (9.7) | ||

| GIT | 2 (6.9) | 17 (6.9) | 11 (8.9) | 6 (4.8) | ||

| Falls | 0 (0) | 21 (8.5) | 4 (3.2) | 17 (13.7) | ||

| Renal | 0 (0) | 16 (6.5) | 6 (4.8) | 10 (8.1) | ||

| Miscellaneous | 6 (20.7) | 55 (22.2) | 31 (25.0) | 24 (19.4) | ||

| LOS, median (IQR) | 13.3 (6.7–35.9) | 6.8 (3.2–13.7) | 0.004 | 7.9 (3.6–15.2) | 5.7 (3.1–11.5) | 0.11 |

| MUST score* | 1.9 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.001 | 1.3 (1.3) | 0.9 (1.2) | 0.03 |

| Nutrition status PG-SGA†, n (%) | ||||||

| Nourished | 5 (17.2) | 121 (48.8) | 0.001 | 50 (40.3) | 71 (57.3) | 0.008 |

| Malnourished | 24 (82.8) | 127 (51.2) | 74 (59.7) | 53 (42.7) | ||

| Patients with PG-SGA ≥7, n (%) | 25 (86.2) | 142 (57.3) | 0.002 | 80 (64.5) | 62 (50.0) | 0.02 |

| QoL, mean (SD) | ||||||

| EQ-5D index‡ | 0.678 (0.226) | 0.709 (0.222) | 0.49 | 0.700 (0.229) | 0.717 (0.217) | 0.31 |

| VAS§ | 55.2 (17.1) | 59.5 (20.1) | 0.28 | 55.9 (20.4) | 62.8 (18.1) | 0.003 |

| Total MET calls, mean (SD) | 0.24 (1.0) | 0.13 (0.4) | 0.38 | 0.10 (0.32) | 0.15 (0.53) | 0.95 |

| Total ICU hours, mean (SD) | 4.3 (19.3) | 1.9 (13.4) | 0.53 | 2.3 (15.5) | 1.5 (11.0) | 0.62 |

*Higher MUST score indicates high risk for malnutrition.

†PG-SGA class dichotomised to PG-SGA A (nourished) and PG-SGA B and C (malnourished).

‡Higher EQ-5D index indicates better QoL.

§Higher VAS indicates better QoL.

CVS, cardiovascular; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life 5 dimension; GIT, gastrointestinal; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of hospital stay; MET, medical emergency team; MUST, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool; PG-SGA, Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment; QoL, quality of life; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Malnutrition was associated with a higher risk of the combined endpoint of readmissions and death within 7 days after discharge (OR 4.57, 95% CI 1.69 to 12.37, P<0.001; table 2). After adjusting for covariates, including age, gender, Charlson Comorbidity Index, LOS, number of medications, principal diagnosis at current admission and hours spent in the ICU during index admission, the association was even stronger for the combined endpoint (OR 5.01, 95% CI 1.69 to 14.75, P=0.009; table 2). Similarly, between 8 and 180 days postdischarge, malnourished patients had higher odds to have a combined endpoint of readmission and death (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.28, P=0.007; table 3), and this remained significant even after adjustment for the above covariates (OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.47, P=0.002; table 3). The p value for the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit was >0.05 for both the adjusted models, indicating a good fit. The variance inflation factors and tolerance were near 1.0 for all variables, excluding significant collinearity. The link test confirmed that the linear approach to model the outcomes was correct. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve (figure 1) shows that the nourished group had significantly fewer readmissions and deaths at 180 days than the malnourished group (log-rank χ2=11.4, P<0.001).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs and 95% CIs (95% CI) for early readmission/death (0–7 days)

| Variable | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

P value |

| Malnourished | 4.57 (1.69 to 12.37) | 0.001 | 5.01 (1.69 to 14.75) | 0.009 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) | 0.73 | 1.00 (0.94 to1.05) | 0.80 |

| Female sex | 0.42 (0.19 to 0.89) | 0.03 | 0.42 (0.17 to 1.04) | 0.06 |

| Total comorbidities | 1.08 (0.95 to 1.23) | 0.25 | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.38) | 0.13 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.16 (0.96 to 1.40) | 0.12 | 1.08 (0.84 to 1.39) | 0.55 |

| Medications during index admission | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.47 | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.02) | 0.12 |

| LOS of index admission | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) | 0.001 | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.05) | 0.02 |

| Admission in last 6 months prior to index admission | 0.77 (0.53 to 1.12) | 0.13 | 0.66 (0.27 to 1.58) | 0.35 |

| Principal diagnosis index admission | ||||

| Reference (respiratory illness) | – | – | – | – |

| CVS | 0.63 (0.23 to 1.75) | 0.38 | 0.63 (0.20 to 2.04) | 0.44 |

| CNS | 0.61 (0.16 to 2.32) | 0.48 | 0.34 (0.06 to 1.93) | 0.23 |

| GIT | 0.54 (0.13 to 2.59) | 0.44 | 0.42 (0.07 to 2.36) | 0.33 |

| Falls | – | – | – | – |

| Urinary | – | – | – | – |

| Miscellaneous | 0.61 (0.23 to 1.61) | 0.31 | 0.35 (0.11 to 1.12) | 0.07 |

| ICU hours during index admission | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.56 | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 0.63 |

| Total MET calls index admission | 1.55 (0.95 to 2.54) | 0.08 | 0.84 (0.31 to 2.22) | 0.72 |

*OR determined using multivariable logistic regression (using early/late readmissions or death as outcome variable).

CNS, central nervous system; CVS, cardiovascular; GIT, gastrointestinal; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of hospital stay; MET, medical emergency team.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs and 95% CIs (95% CI) for late readmission/death (8–180 days)

| Variable | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

P value |

| Malnourished | 1.98 (1.19 to 3.28) | 0.007 | 1.97 (1.12 to 3.47) | 0.009 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | 0.81 | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.03) | 0.94 |

| Female sex | 0.86 (0.51 to 1.44) | 0.56 | 0.93 (0.52 to 1.66) | 0.83 |

| Total comorbidities | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.25) | 0.006 | 1.07 (0.95 to 1.22) | 0.30 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.11 (0.97 to 1.28) | 0.13 | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.23) | 0.85 |

| Medications during index admission | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.14) | 0.008 | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) | 0.17 |

| LOS of index admission | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.45 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.52 |

| Admission in last 6 months prior to index admission | 1.55 (0.96 to 2.53) | 0.07 | 1.38 (0.79 to 2.40) | 0.26 |

| Principal diagnosis index admission | ||||

| Reference (respiratory illness) | – | – | – | – |

| CVS | 1.58 (0.75 to 3.27) | 0.22 | 2.06 (0.91 to 4.70) | 0.08 |

| CNS | 1.09 (0.44 to 2.71) | 0.85 | 1.12 (0.41 to 3.04) | 0.81 |

| GIT | 2.03 (0.71 to 5.73) | 0.18 | 1.91 (0.58 to 6.28) | 0.29 |

| Falls | 0.26 (0.08 to 0.85) | 0.03 | 0.26 (0.07 to 0.89) | 0.03 |

| Urinary | 0.83 (0.28 to 2.41) | 0.72 | 0.71 (0.21 to 2.32) | 0.57 |

| Miscellaneous | 1.40 (0.70 to 2.79) | 0.34 | 1.36 (0.63 to 2.92) | 0.44 |

| ICU hours during index admission | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0.53 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03) | 0.64 |

| Total MET calls index admission | 0.76 (0.41 to 1.39) | 0.36 | 0.66 (0.32 to 1.34) | 0.25 |

*ORs determined using multivariable logistic regression (using early/late readmissions or death as outcome variable).

CNS, central nervous system; CVS, cardiovascular; GIT, gastrointestinal; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of hospital stay; MET, medical emergency team.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for combined outcome in nourished and malnourished.

Discussion

The present study’s results indicate that malnutrition at admission, as determined by the PG-SGA, was a significant predictor of a combined endpoint of readmission or mortality in older general medical patients, during both the early and late periods after hospital discharge. Malnutrition was associated with an almost fourfold increased risk of readmission or mortality within 7 days after discharge, and the risk almost doubled between 8 and 180 days after discharge. Malnutrition remained a significant predictor even after adjustment for other covariates that could have influenced the clinical outcome.

One appealing explanation for these results is that the acute condition responsible for the index admission weakens the patient’s overall health, and malnutrition further compounds this problem with a consequent higher risk of complications or exacerbations of previously stable comorbidities.21 The postdischarge period is a fragile period, referred to as—‘posthospital syndrome’.22 This syndrome has been described as a period of vulnerability due to impaired physiological systems, depleted reserves and lower body resistance against health threats, on top of the recent acute illness responsible for the index admission. The current study’s results introduce another dimension to this theory: impaired nutritional status may play a significant role in the postdischarge period beyond 7 days. The acute illness and the stress of the index admission may exacerbate malnutrition, possibly inducing a relapse or predisposing the patient to new acute illnesses that increase the risk of readmission or mortality.23 24

The present study’s results are in line with Mogensen et al, who found that malnourished patients who survived intensive care admission had higher 90-day mortality (OR 3.72, 95% CI 1.2 to 6.3) and that malnutrition was a significant predictor of their 30-day unplanned hospital readmission.25 Studies in patients with heart failure have suggested that malnutrition may contribute to the progression of the underlying heart disease due to low-grade inflammation leading to poor outcomes and was a significant predictor of readmissions.26

Older general medical patients are known to have substantial long-term morbidity and mortality. Known risk factors for adverse events following discharge include multiple comorbidity, severity of index admission and institutional care rather than domiciliary care.2 27 Hospital readmissions represent a multifaceted problem that require a better understanding.21 Presumably there are other unknown factors that influence patient outcomes after discharge. The present study illustrates that early and late postdischarge patient outcomes appear to be associated with the presence of malnutrition during admission. While causation cannot be inferred from an observational study, the malnutrition postdischarge outcome has biological plausibility.

To date, no study has included nutritional status in the development of a predictive tool for readmissions and this area needs further research. Studies do suggest that nutritional intervention initiated early during hospitalisation, by providing high-energy protein supplements with a continuation posthospital discharge, does have a favourable impact on nutritional parameters and reduces the LOS; however, its impact on mortality and readmissions is unclear, and such an intervention may be too late for some.28 29 While the ideal intervention to improve nutritional status in hospitalised patients has yet to be identified, the solution may lie in recognising and managing malnutrition in the community before any hospital admission.30

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is a single-centre study in a tertiary care hospital. The case mix of patients discharged from this hospital may differ from that of other hospitals; thus, the results may not be generalisable particularly to community hospitals, although it is likely to be similar to other academic hospitals in Australia. The study was unable to adjust its analysis for functional status or other factors, such as appropriateness of drugs, clinical stability at discharge or social factors that might influence readmission. This study involved older general medical patients who frequently suffer from multiple comorbidities, and our results may not be applicable to relatively younger subspecialty patients with single organ system involvement.

One of the study’s strengths is that it was a prospective study and that the malnutrition diagnosis was confirmed by a dietitian using a comprehensive nutrition assessment tool. The study also assessed all readmissions in all state hospitals, unlike some other studies that were only able to capture readmissions to a single hospital.

Implications

This study has several implications. Transitions of care should focus on the acute condition and on the patient’s nutritional status, because the latter may increase the risk of readmission or death. There is a need for future well-designed studies to examine the beneficial effects of an intervention targeting malnutrition and whether this intervention prevents readmissions and mortality. In the interim, nutritional intervention should be most effective if begun early during admission and it should be continued in the community following discharge by referral to either a community dietitian or follow-up at an outpatient dietetic clinic. Overall, public health policies to optimise nutrition of those over 60 years of age may result in a reduction in healthcare usage.

Conclusion

Impaired nutritional status at admission predicts poor clinical outcomes in both early and late postdischarge periods as determined by readmissions and mortality in older general medical patients and a targeted nutritional intervention may prove beneficial in malnourished patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YS, CT and MM designed the study and YS, CT, BK and MM carried out the analysis and interpretation. YS, PH and CH provided statistical input. YS and RS undertook recruitment. YS and CT wrote the manuscript, which was edited by BK, RS and MM. All authors approved final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from Southern Adelaide Human Research Committee (SAC HREC; approval number 273.14-HREC/14/SAC/282) on 21 July 2014.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians. Hospitals on the edge? The time for action. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2012. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/hospitals-edge-time-action [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balla U, Malnick S, Schattner A. Early readmissions to the department of medicine as a screening tool for monitoring quality of care problems. Medicine 2008;87:294–300. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181886f93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. . Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:355–63. 10.1001/jama.2012.216476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klausen HH, Petersen J, Bandholm T, et al. . Association between routine laboratory tests and long-term mortality among acutely admitted older medical patients: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:62 10.1186/s12877-017-0434-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puhan MA, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, et al. . Respiratory rehabilitation after acute exacerbation of COPD may reduce risk for readmission and mortality -- a systematic review. Respir Res 2005;6:54 10.1186/1465-9921-6-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, et al. . Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:444–50. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–28. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prescott HC, Sjoding MW, Iwashyna TJ. Diagnoses of early and late readmissions after hospitalization for pneumonia. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:1091–100. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-142OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham KL, Marcantonio ER. Differences between early and late readmissions among patients. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:650 10.7326/L15-5149-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. . Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306:1688–98. 10.1001/jama.2011.1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stratton RJ, Hébuterne X, Elia M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of oral nutritional supplements on hospital readmissions. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12:884–97. 10.1016/j.arr.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma Y, Thompson C, Shahi R, et al. . Malnutrition in acutely unwell hospitalized elderly - ‘The skeletons are still rattling in the hospital closet’. J Nutr 2017:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlton K, Nichols C, Bowden S, et al. . Poor nutritional status of older subacute patients predicts clinical outcomes and mortality at 18 months of follow-up. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012;66:1224–8. 10.1038/ejcn.2012.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruizenga HM, Wierdsma NJ, van Bokhorst MA, et al. . Screening of nutritional status in the Netherlands. Clin Nutr 2003;22:147–52. 10.1054/clnu.2002.0611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stratton RJ, King CL, Stroud MA, et al. . ’Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool' predicts mortality and length of hospital stay in acutely ill elderly. Br J Nutr 2006;95:325–30. 10.1079/BJN20051622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desbrow B, Bauer J, Blum C, et al. . Assessment of nutritional status in hemodialysis patients using patient-generated subjective global assessment. J Ren Nutr 2005;15:211–6. 10.1053/j.jrn.2004.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall S, Young A, Bauer J, et al. . Malnutrition in geriatric rehabilitation: prevalence, patient outcomes, and criterion validity of the Scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment and the Mini Nutritional Assessment. J Acad Nutr Diet 2016;116:785–94. 10.1016/j.jand.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushnell DM, Martin ML, Ricci JF, et al. . Performance of the EQ-5D in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Value Health 2006;9:90–7. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole A, Shah K, Mulhern B, et al. . Valuing EQ-5D-5L health states ’in context' using a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s10198-017-0905-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity: John Wiley & Sons, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donzé J, Lipsitz S, Bates DW, et al. . Causes and patterns of readmissions in patients with common comorbidities: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2013;347:f7171 10.1136/bmj.f7171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368:100–2. 10.1056/NEJMp1212324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alzahrani SH, Alamri SH. Prevalence of malnutrition and associated factors among hospitalized elderly patients in King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:136 10.1186/s12877-017-0527-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzola P, Ward L, Zazzetta S, et al. . Association between preoperative malnutrition and postoperative delirium after hip fracture surgery in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1222–8. 10.1111/jgs.14764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mogensen KM, Horkan CM, Purtle SW, et al. . Malnutrition, critical illness survivors, and postdischarge outcomes: a cohort study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017. 10.1177/0148607117709766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agra Bermejo RM, González Ferreiro R, Varela Román A, et al. . Nutritional status is related to heart failure severity and hospital readmissions in acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2017;230:108–14. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.12.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham KL, Wilker EH, Howell MD, et al. . Differences between early and late readmissions among patients: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:741–9. 10.7326/M14-2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bally MR, Blaser Yildirim PZ, Bounoure L, et al. . Nutritional support and outcomes in malnourished medical inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:43–53. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma Y, Thompson C, Kaambwa B, et al. . Investigation of the benefits of early malnutrition screening with telehealth follow up in elderly acute medical admissions. QJM 2017:639–47 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1093/qjmed/hcx095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milne AC, Potter J, Vivanti A, et al. . Protein and energy supplementation in elderly people at risk from malnutrition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD003288 10.1002/14651858.CD003288.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.