Abstract

Mucormycosis is a rare and life-threatening fungal infection of the Mucorales order occurring mainly in immunosuppressed patients. The most common forms are rhinocerebral but pulmonary or disseminated forms may occur. We report the case of a 61-year-old patient in whom pulmonary mucormycosis was diagnosed during his first-ever episode of diabetic ketoacidosis. While receiving liposomal amphotericin B, a sinusal aspergillosis due to Aspergillus fumigatus occurred. Evolution was slowly favorable under antifungal tritherapy by liposomal amphotericin B, posaconazole and caspofungin.

Abbreviations: GVH, raft Versus Host disease; BAL, Bronchoalveolar Lavage; PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction

Keywords: Pulmonary mucormycosis, Sinusal aspergillosis, Fungal infection, Bronchial obstruction, Diabetic ketoacidosis

1. Introduction

Within the Mucorales, Rhizopus sp, Mucor sp. and Lichtheimia sp are the most frequent fungi involved in human mucormycosis. The main process of infection consists of inhalation of ubiquitous saprophytic spores. No inter-human contamination has been described to date. The main risk factors are severe chronic neutropenia, systemic corticotherapy, hematological malignancies, severe graft versus host disease (GVHD), bone marrow transplantation, diabetic ketoacidosis or uncontrolled diabetes, iron overload, prior exposure to voriconazole, severe renal insufficiency and protein-energy malnutrition [1].

While the disease occurs in 40% of cases in the rhino-orbital or cerebral form (mostly in diabetic patients), pulmonary presentations, primary cutaneous (mostly in premature infants), gastrointestinal and disseminated forms in severely immunosuppressed patients [2] have been described. The differential diagnosis with aspergillosis can be challenging but they are two different diseases that do not respond to the same treatment. Indeed, the Mucorales have a natural resistance to voriconazole which is the first-line treatment for aspergillosis [3].

2. Case

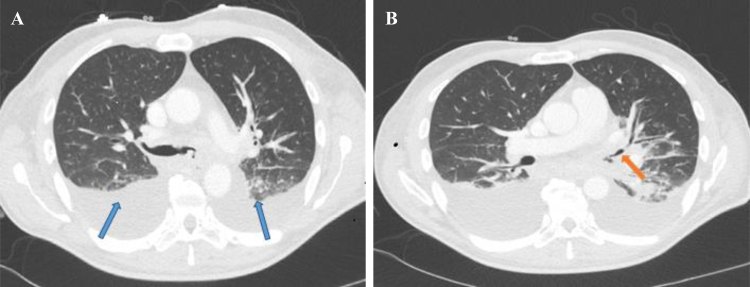

We report the case of a 61-year-old ex-smoker (10 pack-years). He was a retired automobile worker who had been exposed to asbestos. He had no major medical history. He was hospitalized on 06/24/2014: D0 (day 0) for his first-ever episode of diabetic ketoacidosis, after 3 weeks of polyuropolydipsic syndrome. Since he also had hemoptysis, a CT scan was performed and revealed bi-basal condensation and infiltration of the left main bronchus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Initial thoracic CT scan, axial section. A: bi-basal condensation (blue arrows). B: infiltration of left main bronchus (orange arrow).

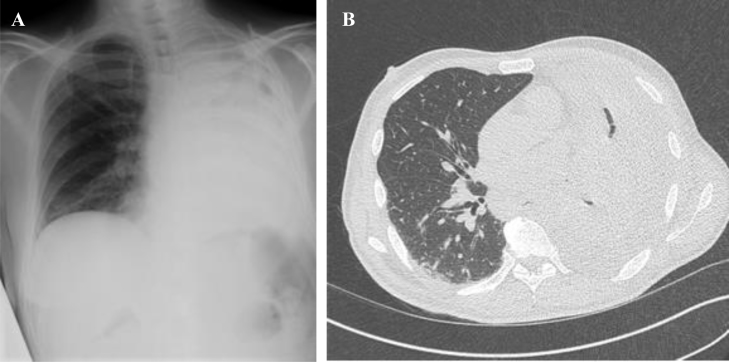

Bronchoscopy at D7 showed granulation tissue in the left main bronchus which was sampled for pathologic analysis. Histopathologic examination realized out of the hospital center of Bordeaux revealed the presence of septate hyphae with narrow angles suggesting aspergillus infection. Treatment with voriconazole was therefore initiated at D10. The work-up did not reveal any primary or secondary immunodeficiency in particular no neutropenia, negative HIV status, no evidence of a neoplasia on the thoracoabdominal CT-scan. After D28, however, a new thoraco-abdomino-pelvic scan revealed complete atelectasis of the left lung with complete obstruction of the left main bronchus and left pleural effusion. There was no evidence of sinonasal, encephalic or abdominal infection (Fig. 2). Transthoracic echocardiography ruled out endocarditis.

Fig. 2.

A: Frontal Chest X-ray: left lung atelectasis and suspicion of pleural effusion. B: Axial section of thoracic CT scan: left lung atelectasis with obstruction of left main bronchus and left pleural effusion.

The clinical worsening under voriconazole in the context of diabetes mellitus with ketoacidosis therefore suggested the diagnosis of pulmonary mucormycosis, which could be a differential diagnosis of aspergillosis.

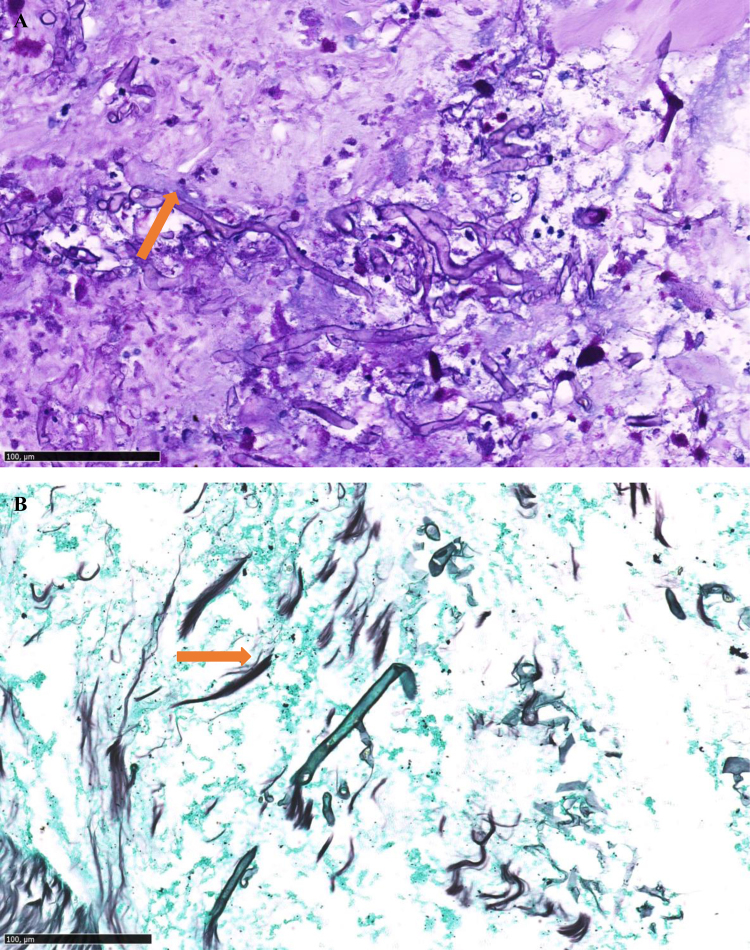

A new endoscopy at D30 revealed a non-catheterisable left bronchial tree that was obstructed by granulation tissue. Histological analysis showed the presence of non-septate mycelial bodies suggestive of Mucorales hyphae (Fig. 3). Culturing of this histopathologic tissue didn’t allow to isolate the pathogen. Galactomannan assay (Platelia© Aspergillus Ag Kit, Bio-Rad) on a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was negative. Mycological cultures of BAL and pulmonary biopsy did not allow recovery of any mold isolate. Molecular diagnosis of Mucorales was performed, and showed positive quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using hydrolysis probes targeting Mucor/Rhizopus species both on formalin-fixed parafined embedded pedicle biopsy and bronchial aspirate [4]. Nevertheless, this result sampled at D30 was obtained only later at D45. However, no circulating blood DNA was concomitantly detected by qPCR.

Fig. 3.

A: Fragments of stained bronchial mucosa (PAS ×140): presence of non-septate hyphae (orange arrow), B: Fragments of stained bronchial mucosa (Gomori Grocott ×170): presence of non-septate hyphae (orange arrow).

Liposomal amphotericin B 10 mg/kg/day was administered one month from the beginning of the treatment at D31, according to the opinion of the reference center.

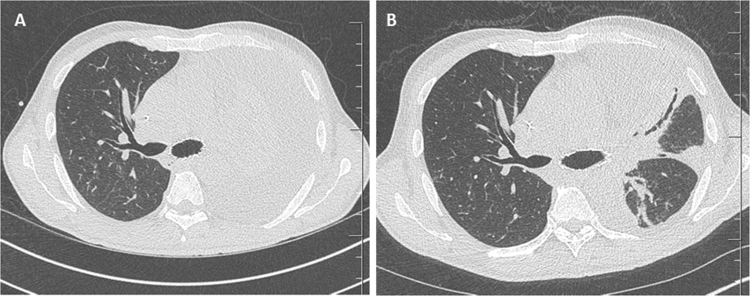

The clinical evolution was favorable with rapid withdrawal of oxygen at D58 despite severe persistent malnutrition. A control endoscopy at D64 revealed an extension of the endobronchial lesions to the carina. A bronchoscopy to relieve obstruction was performed with insertion of a stent in the left main bronchus (Fig. 5). Thoracic surgery was discussed but proved impossible because the carina was invaded. The various biopsies performing during the endoscopies for the follow-up were negative.

Fig. 5.

A and B: CT images at one and two months of treatment, respectively.

The treatment was extended at D64 to liposomal amphotericin B 5 mg/kg (onset of renal failure with a creatinine clearance 25 mL/min), caspofungin and posaconazole.

Initially the patient has been treated for one month by intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg/day. The treatment was extended at D64 by oral posaconazole 400 mg twice daily and intravenous caspofungin 50 mg/day. So two months after the start of treatment with liposomal amphotericin B including one month of tri-therapy with caspofungin and posaconazole a sinus CT scan revealed filling of the left maxillary sinus suggesting fungal ball while the initial sinus CT scan was normal.

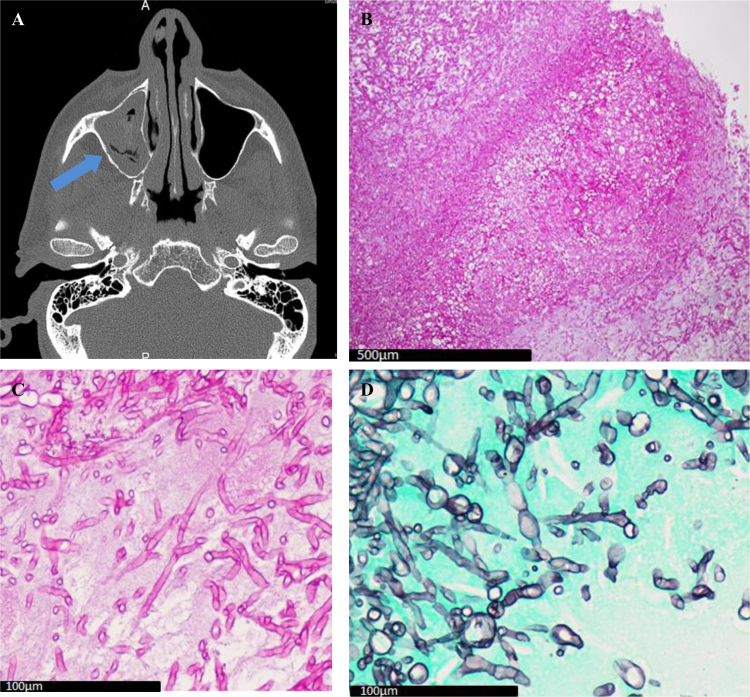

This diagnosis was evocated by histological examination at D85 which highlighted the presence of septate mycelial hyphae with narrow angles (Fig. 4) and confirmed by culture of the sinus sample which was positive and allowed the identification of an Aspergillus fumigatus. A meatotomy was performed.

Fig. 4.

A: Sinus CT axial section: Filling of left maxillary sinus (blue arrow); B: Sinus biopsy (PAS ×10): Aspergillus fungus ball; C: Sinus biopsy (PAS ×60): Aspergillus hyphae; D: Sinus biopsy (Gomori Grocott × 60): Aspergillus hyphae.

According to the EORTC/MSG [5] this diabetic immunocompromised patient therefore had both proven pulmonary mucormycosis Mucor/Rhizopus species and Aspergillus fumigatus fungal ball on left maxillary sinus without bone or tissular invasion.

Unfortunately, Aspergillus fumigatus subculture didn’t allow performing anti-fungal testing regarding amphotericin B susceptibility because the organism didn’t grow in subculture.

The antifungal tri-therapy was discontinued after 1 year on account of the favorable clinical and radiological evolution and because qPCR for Mucorales in circulating blood and bronchial biopsies on subsequent bronchial endoscopies remained negative.

3. Discussion

We report the case of a 61-year-old patient suffering from fungal co-infection with proven mucormycosis and proven sinusal aspergillosis in the setting of uncontrolled diabetes.

The diagnosis of infection with Mucorales should be considered whenever there is clinical and/or endoscopic evidence of fungal infection, especially if the patient is diabetic or immunocompromised.

In this patient, both diseases coexisted with bronchopulmonary infection with a Mucor/Rhizopus species and aspergillosis sinus due to Aspergillus fumigatus. In a review of 929 cases of zygomycosis, the sinuses were the most common location (39% of cases), Rhizopus was the most frequently involved causal agent and proven or probable co-infection with Aspergillus sp. occurred in 44% of cases [6]. To date, only two cases to our knowledge involving mucormycosis and aspergillosis at the same time, namely the oropharyngeal sphere, has been reported. It was in a patient with Castleman's disease [7] and in a diabetic patient [8].

Pathologic analysis is mandatory in such cases. Microscopically, the Mucorales hyphae are not septate and are thicker than Aspergillus sp. hyphae. However, even when the hyphae are not septate, a pathologist's expertise may be necessary and multidisciplinary collaboration between pathologists and mycologists is indispensable [9], [10], [11]. Culture of biopsies is positive in only 50% of cases. This is especially the case for immunocompromised patients in whom bronchoalveolar lavage produces low culture yields, especially hematologic patients. [9] Importantly, there is a significant risk of environmental contamination during cultivation, so the mycology laboratory performing the procedure should be aware of this methodological pitfall and make sure that their culture techniques are totally aseptic. Furthermore, beta-D-glucan and galactomannan antigenemia are negative in mucormycosis. In our case, the 3 qPCR assays targeting Mucor/Rhizopus, Lichtheimia (formerly Absidia), and Rhizomucor were of great help in the diagnosis as previously described in several studies [4], [12], [13].

The differential diagnosis of mucormycosis and aspergillosis is important because their treatments are different [14]. As a first line, aspergillosis is treated with voriconazole while the Mucorales are naturally resistant to it [15]. Thus, in case of suspected fungal infection, an unfavorable evolution with voriconazole is a strong argument for mucormycosis. The Mucorales also show resistance in vitro to fluconazole and flucytosine while their sensitivity to itraconazole is variable. The most active agents in vitro are amphotericin B and posaconazole [14], [16] so they are the treatment of choice.

Treatment should be continued for a minimum of twelve weeks but especially until all the clinical and radiological symptoms resolved and cultures have become negative. Immunity should also be strengthened as far as possible and risk factors such as diabetes and protein-energy malnutrition should be treated or kept under control [1]. Surgery should always be considered in the management of mucormycosis. In our patient the nature of the lesions invading the carina ruled out such initial management but surgical resection of necrotic tissue must be the discussed in case of localized disease. It allows systemic treatment to reach the infected areas isolated by vascular thrombotic events, and reduces the fungal burden [11], [17].

Interestingly, the Mucorales infection in our patient occurred in a setting of a first-ever episode of diabetic ketoacidosis. Hyperglycemia, and particularly ketoacidosis, impairs the ability of neutrophils to destroy the Mucorales hyphae. Moreover, ketoacidosis increases the availability of free iron which is used as a growth factor by Mucorales [18], [19]. Unfortunately, deferasirox, an iron chelator was associated with a higher mortality rate at 90 days in clinical trials [20], [21].

In conclusion, the diagnosis of mucormycosis should be considered in an immunocompromised patient with either rhino-orbital or pulmonary involvement. Other pseudotumoral forms may also occur. It is essential to perform several biopsies in order to obtain a positive culture. Co-infections are common, as this case clearly demonstrates. Multidisciplinary collaboration between clinicians, pathologists, mycologists and a reference center is mandatory as early as possible to diagnose this disease, which carries a poor prognosis.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to Dr. Minh Triet Ngo at the Suresnes Hospital and to Pr. Tunon de Lara, Dr. Dromer, Dr. Demant and Dr. Accoceberry for participating in the management of the patient. Thanks go to Dr. Claire Castain for providing the pathology images of the Aspergillus fumigatus fungal ball and to Dr Clemence Pierry for providing images of the Mucorales hyphae and for reading the work. We also thank Ray Cooke for translating the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no disclosure to make.

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Kontoyiannis D.P., Lewis R.E. How I treat mucormycosis. Blood. 2011;118(5):1216–1224. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-316430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis R.E., Kontoyiannis D.P. Epidemiology and treatment of mucormycosis. Future Microbiol. 2013;8(9):1163–1175. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis R.E., Lortholary O., Spellberg B., Roilides E., Kontoyiannis D.P., Walsh T.J. How does antifungal pharmacology differ for mucormycosis versus aspergillosis? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 1):S67–S72. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millon L., Larosa F., Lepiller Q., Legrand F., Rocchi S., Daguindau E. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction detection of circulating DNA in serum for early diagnosis of mucormycosis in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2013;56(10):e95–e101. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Pauw B., Walsh T.J., Donnelly J.P., Stevens D.A., Edwards J.E., Calandra T. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European organization for research and treatment of cancer/invasive fungal infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of allergy and infectious diseases Mycoses study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46(12):1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roden M.M., Zaoutis T.E., Buchanan W.L., Knudsen T.A., Sarkisova T.A., Schaufele R.L. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;41(5):634–653. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maiorano E., Favia G., Capodiferro S., Montagna M.T., Lo Muzio L. Combined mucormycosis and aspergillosis of the oro-sinonasal region in a patient affected by Castleman disease. Virchows Arch. 2005;446(1):28–33. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torres-Damas W., Yumpo-Cárdenas D., Mota-Anaya E. Coinfection of rhinocerebral mucormycosis and sinus aspergillosis. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica. 2015;32(4):813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luna M.D.M., Warraich M.D.I., Han M.D.X.Y., May Ph.D.G.S., Kontoyiannis M.D.D.P., Tarrand M.D.J.J. Diagnosis of invasive septate mold infections: a correlation of microbiological culture and histologic or cytologic examination. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2003;119(6):854–858. doi: 10.1309/EXBV-YAUP-ENBM-285Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh T.J., Gamaletsou M.N., McGinnis M.R., Hayden R.T., Kontoyiannis D.P. Early clinical and laboratory diagnosis of invasive pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and disseminated mucormycosis (zygomycosis) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 1):S55–S60. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee F.Y.W., Mossad S.B., Adal K.A. Pulmonary mucormycosis: the last 30 years. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999;159(12):1301. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.12.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boch T., Reinwald M., Postina P., Cornely O.A., Vehreschild J.J., Heußel C.P. Identification of invasive fungal diseases in immunocompromised patients by combining an Aspergillus specific PCR with a multifungal DNA-microarray from primary clinical samples. Mycoses. 2015;58(12):735–745. doi: 10.1111/myc.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millon L., Herbrecht R., Grenouillet F., Morio F., Alanio A., Letscher-Bru V. Early diagnosis and monitoring of mucormycosis by detection of circulating DNA in serum: retrospective analysis of 44 cases collected through the French Surveillance Network of Invasive Fungal Infections (RESSIF) Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22(9):810.e1–810.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tissot F., Agrawal S., Pagano L., Petrikkos G., Groll A.H., Skiada A. ECIL-6 guidelines for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis and mucormycosis in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Haematologica. 2017;102(3):433–444. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.152900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limper A.H., Knox K.S., Sarosi G.A., Ampel N.M., Bennett J.E., Catanzaro A. An official American thoracic society statement: treatment of fungal infections in adult pulmonary and critical care patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;183(1):96–128. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2008-740ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Q.N., Fothergill A.W., McCarthy D.I., Rinaldi M.G., Graybill J.R. In vitro activities of posaconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and fluconazole against 37 clinical isolates of zygomycetes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46(5):1581–1582. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1581-1582.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tedder M., Spratt J.A., Anstadt M.P., Hegde S.S., Tedder S.D., Lowe J.E. Pulmonary mucormycosis: results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1994;57(4):1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rammaert B., Lanternier F., Poirée S., Kania R., Lortholary O. Diabetes and mucormycosis: a complex interplay. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38(3):193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Artis W.M., Fountain J.A., Delcher H.K., Jones H.E. A mechanism of susceptibility to mucormycosis in diabetic ketoacidosis transferrin and iron availability. Diabetes. 1982;31(12):1109–1114. doi: 10.2337/diacare.31.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soummer A., Mathonnet A., Scatton O., Massault P.P., Paugam A., Lemiale V. Failure of deferasirox, an iron chelator agent, combined with antifungals in a case of severe zygomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52(4):1585–1586. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01611-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spellberg B., Ibrahim A.S., Chin-Hong P.V., Kontoyiannis D.P., Morris M.I., Perfect J.R. The Deferasirox-AmBisome Therapy for Mucormycosis (DEFEAT Mucor) study: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67(3):715–722. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]