Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are complex neurological disorders for which the prevalence in the U.S. is currently estimated to be 1 in 50 children. A majority of cases of idiopathic autism in children likely result from unknown environmental triggers in genetically susceptible individuals. These triggers may include maternal exposure of a developing embryo to environmentally relevant minute concentrations of psychoactive pharmaceuticals through ineffectively purified drinking water. Previous studies in our lab examined the extent to which gene sets associated with neuronal development were up- and down-regulated (enriched) in the brains of fathead minnows treated with psychoactive pharmaceuticals at environmental concentrations. The aim of this study was to determine whether similar treatments would alter in vitro expression of ASD-associated synaptic proteins on differentiated human neuronal cells. Human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells were differentiated for two weeks with 10μM retinoic acid (RA) and treated with environmentally relevant concentrations of fluoxetine, carbamazepine or venlafaxine, and flow cytometry technique was used to analyze expression of ASD-associated synaptic proteins. Data showed that carbamazepine individually, venlafaxine individually and mixture treatment at environmental concentrations significantly altered the expression of key synaptic proteins (NMDAR1, PSD95, SV2A, HTR1B, HTR2C and OXTR). Data indicated that psychoactive pharmaceuticals at extremely low concentrations altered the in vitro expression of key synaptic proteins that may potentially contribute to neurological disorders like ASD by disrupting neuronal development.

Keywords: Psychoactive pharmaceuticals, Environmental Toxicology, Drinking water, Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD)

1. Introduction

With the prevalence of 1 in 50 children in the USA [1], autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder that lasts throughout a person’s life [2]. While several studies found that genetic factors such as mutations in candidate genes (high and low susceptibility) and copy number variations (CNV) [3–6] might impact risk for ASD, these factors are responsible for only 2–3% of ASD cases [7, 8].

Evidence indicates that other unknown factor(s) contribute to the etiology of idiopathic ASD [7, 9–11]. Humans interact with approximately 3000 synthetic chemicals via food, air and water [9]. These synthetic chemicals may serve as environmental factors that act as a trigger in genetically susceptible individuals [7, 9–12]. Our study focused on a specific class of potential toxicants, pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCP) [13]. PPCPs mainly involved psychoactive pharmaceuticals, which have been detected in the drinking water at low concentrations [14, 15].

Psychoactive pharmaceuticals are among the most highly prescribed classes of drug in United States [13, 14, 16] and patient excretions still contain active metabolites that have considerably long half-lives [14, 17]. Waste-water treatment plants release PPCP-contaminated water into surface water such as rivers and lakes [17]. Due to inefficient treatment of sewage water in waste-water treatment plants, the active metabolites reach drinking water in minute concentrations [14]. As their metabolites have long half-lives, it is postulated that the environmentally present psychoactive pharmaceuticals might act as a trigger in genetically susceptible individuals by disturbing the process of synaptogenesis or synapse formation, especially during development [9, 16, 18–20].

To address this hypothesis, our lab previously treated juvenile fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) with psychoactive pharmaceuticals (fluoxetine, venlafaxine and carbamazepine) individually and in mixtures at environmentally relevant concentrations, and observed that gene sets associated with neuronal development, regulation and growth were altered [13, 14]. We identified that synaptic proteins were significantly up- and down-regulated in fish brains (Table 1). The protein products of these genes are known to play a key role in synaptogenesis, and are also found to be associated with ASD [3, 21, 22].

Table 1.

List of synaptic genes that were significantly up- and down-regulated in fathead minnow brains treated with a mixture treatment of psychoactive pharmaceuticals [13].

| Synaptic proteins | Gene Symbol | Gene expression in Fish brains |

|---|---|---|

| Gamma-Aminobutyric acid receptors | GABRA3, GABRA6 | Upregulated |

| Ligand-gated glutamate receptors (N-methyl-D-aspartate) | NMDAR1, NMDAR2A, NMDAR2D | Upregulated |

| Oxytocin | OXTR | Upregulated |

| Serotonin | HTR1B, HTR2C | Downregulated |

| Post-synaptic density | PSD95 | Downregulated |

| Synaptic vessicle | SV2A | Downregulated |

The aim of the present study was to examine whether psychoactive pharmaceuticals (fluoxetine, venlafaxine and carbamazepine) at environmental concentrations alter in vitro expression of ASD-associated synaptic proteins in human neurons. Specifically, we predicted that 1) protein products of genes (Table 1) which were enriched in fish brains would be altered in response to pharmaceuticals treatment at very low concentrations, and 2) other key synaptic protein expression would be more likely to be dysregulated, because altered synaptogenesis has been proposed as a pathophysiological mechanism of ASD in other studies. Thus expression profiles of autism-associated proteins in differentiated human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell line were determined using flow cytometry.

On identifying the expression change in ASD-associated synaptic proteins, we hope that this in vitro system will serve as a model to dissect the mechanisms underlying altered synaptogenesis, which is still considered as a conundrum in the etiology of idiopathic ASD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Cell culture and differentiation

Human SK-N-SH cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC #HTB-11). Cells were cultured in polystyrene tissue culture flasks (Corning) as a monolayer in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM; ATCC). This medium was supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-neomycin (Sigma). As this cell line is a mixture of different cells, retinoic acid (RA; Sigma) was used for differentiating SK-N-SH cells [23] into more neuronal cells [24]. Approximately 30,000 cells (per well in 6-well plates) were cutured in supplemented EMEM media for two days, followed by RA (10μM) treatment for two weeks and media was replaced every 3–4 days [23, 25]. Using light microscopy, differentiated neuronal cultures were validated with the presence of neuronal cell markers (NeuN, PSD95 and NCAM) during the differentiation process [23, 26] (Refer supplementary information).

2.2 Pharmaceuticals Treatments

Stock solutions (10mM) of active metabolites of fluoxetine (FLX; Sigma F133), venlafaxine (VNX; Sigma D2069) and carbamazepine (CBZ; Sigma C4206) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After differentiation for 2 weeks, cells were treated individually and in mixtures with high (FLX 1mg/l; VNX 5mg/l; CBZ 10mg/l), medium (FLX 10μg/l; VNX 50μg/l; CBZ 100μg/l), low (FLX 1μg/l; VNX 5μg/l; CBZ 10μg/l) concentration ranges. Control cells were treated with DMSO (vehicle) only, and the final concentration of DMSO in the cultures was less than 0.07%. Cells were treated with pharmaceuticals for 48hr in EMEM media without FBS to avoid any binding of pharmaceuticals with serum proteins. All of the treatments were shown not to affect overall cell viability with respect to control (no treatment), based on the adherent nature of the monolayers and by CyQuant Viability Assay (Life Technologies) [27]. After treatment for 48 hours, cells were collected with Versene solution (Gibco).

2.3 Antibodies for synaptic proteins

Following antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). NMDAR1 (ab109182), NCAM (ab75813), PSD95 (ab2723), SV2A (ab49572), HTR1B (sc1460-R), HTR2C (sc10802), GRM4 (sc99043), OXTR (sc33209), GABRA6 (sc7359), NeuN (mab377), appropriate Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibodies (A11008, A11078).

2.4 Flow Cytometry Analysis

Antibody staining was conducted using a protocol modified from Pacheco et al. 2004 [28]. SK-N-SH cells (1×106) were fixed with 500μl 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Cells were washed with ice-cold 500μl PBS and centrifuged to remove supernatant at 3500rpm for 5 min. Cells were then permeabilized in 0.1% Tween 20 for 20 min. Cells were again washed and centrifuged 3500rpm for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in blocking buffer (PBS, 10% BSA, 300mM glycine) and left for 20 min. Cells were incubated with 1μg/200μl of primary antibodies (Anti-NMDAR1, NCAM, PSD95, SV2A, NMDAR2A, HTR1B, HTR2C, GRM4, OXTR, GABRA6, NeuN) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by washing with PBS twice. After re-suspending in 200μl of blocking buffer, 1μg Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody was added to cells and kept for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. After washing twice with PBS, cells were analyzed on a FACS Calibur Flow Cytometer using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Gates were drawn using a side scatter x forward scatter dot plot to select the major cell population, omitting dead cell debris and cellular clumps. Unstained cells and cells labeled with only secondary antibody were also analyzed to determine autofluorescence and non-specific binding of secondary antibody, and background levels were subtracted from all median fluorescence intensity values reported in the data.

2.5 Statistical approach

Flow cytometry data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test to determine if controls were significantly different (significance defined as P <0.05) than pharmaceutical treatments. Experiments were replicated five times, and data are presented as mean ± SEM.

3. Results

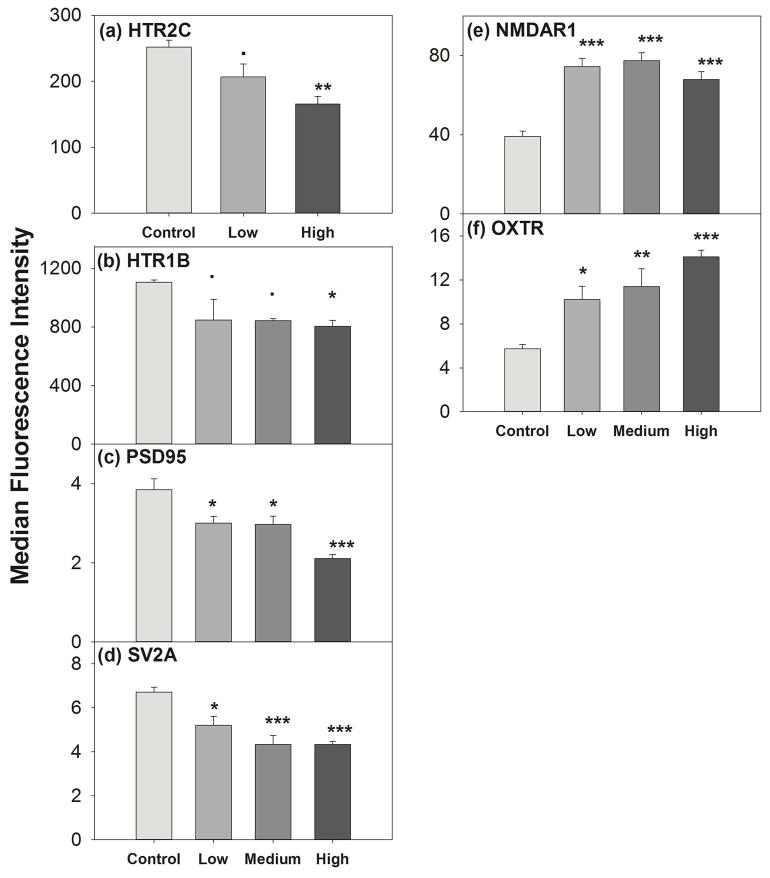

3.1 Carbamazepine (CBZ) treatment at environmental concentration

In our study, we found that N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDAR1) and oxytocin (OXTR) protein expression was increased significantly at all concentrations compared to control (Fig. 1). In contrast, we found carbamazepine treatment significantly decreased expression of post-synaptic density (PSD95), synaptic vessicle (SV2A), and serotonin (HTR2C and HTR1B) synaptic proteins (Fig. 1). No significant change was noted in expression of other synaptic proteins (NCAM, GRM4, GABRA6 and NeuN, data not shown). This result demonstrated that carbamazepine at low concentrations altered in vitro expression of a subset of synaptic proteins which was consistent with the fish study.

Fig. 1. Carbamazepine treatment on synaptic proteins expression.

Differentiated SK-N-SH cells were cultured and treated with carbamazepine for 48 hr. After fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), cells were incubated for 30 min at RT with primary antibodies and then incubated with Alexa488-labeled secondary antibody. The median fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry analysis. Data were analyzed using one way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons of treatments to controls. Symbols above bars indicate significant differences from the control after Dunnett’s adjustment for family-wise type I error at significance level: “***” = 0.001, “**” = 0.01, “*” = 0.05, “.” = 0.1. Error bars represent SEM.

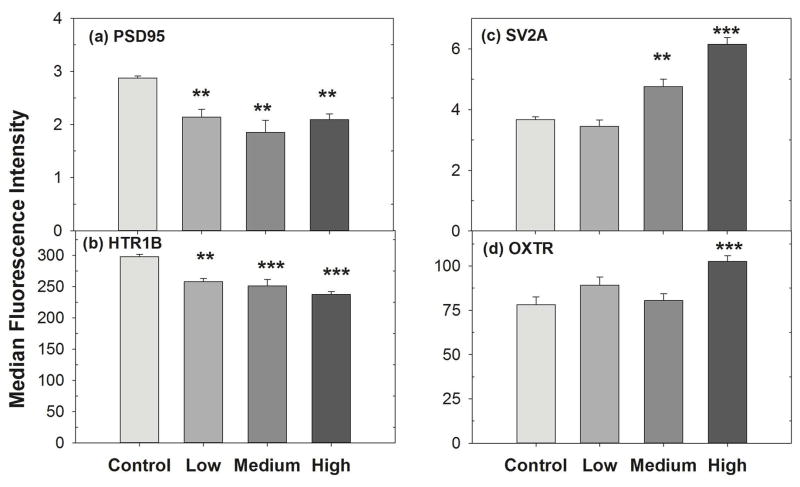

3.2 Venlafaxine (VNX) treatment at environmental concentration

We then sought to determine the effect of venlafaxine on synaptic protein expression at environmental concentrations. To accomplish this, we treated differentiated SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells with venlafaxine in three concentrations (5μg/l, 50μg/l, 5mg/l). Concentrations were chosen based on observations in our previous fish study [13].

We found that SV2A and OXTR synaptic protein expression was increased significantly at medium and high concentrations compared to control (Fig. 2). In contrast, we found venlafaxine treatment decreased the expression of PSD95 and HTR1B synaptic proteins significantly. No significant change was noted in other (HTR2C, NMDAR1, NCAM, GRM4, GABRA6 and NeuN, data not shown) synaptic protein expression. This result reiterates the effect of psychoactive pharmaceuticals at very low concentrations on synpatic protein expression, which was consistent with the fish study.

Fig. 2. Venlafaxine treatment on synaptic proteins expression.

Differentiated SK-N-SH cells were cultured and treated with venlafaxine for 48 hr. After fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), cells were incubated for 30 min at RT with primary antibodies and then incubated with Alexa488-labeled secondary antibody. The median fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry analysis. Data were analyzed using one way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons of treatments to controls. Symbols above bars indicate significant differences from the control after Dunnett’s adjustment for family-wise type I error at significance level: “***” = 0.001, “**” = 0.01, “*” = 0.05, “.” = 0.1. Error bars represent SEM.

3.3 Fluoxetine (FLX) treatment at environmental concentration

The data summarized above provide evidence that psychoactive pharmaceuticals altered synaptic protein expressions at environmental concentrations. For a more concise comparison, another psychoactive pharmaceutical, fluoxetine was examined. SK-N-SH cells were incubated with fluoxetine in three concentrations (1μg/l, 10μg/l, 1mg/l) for 48 hr. Concentrations were chosen based on observations in our previous fish study.

Interestingly, no significant change in the expression of synaptic proteins (PSD95, SV2A, OXTR, HTR1B, HTR2C, NMDAR1, NCAM, GRM4, GABRA6 and NeuN, data not shown) was found compared to controls.

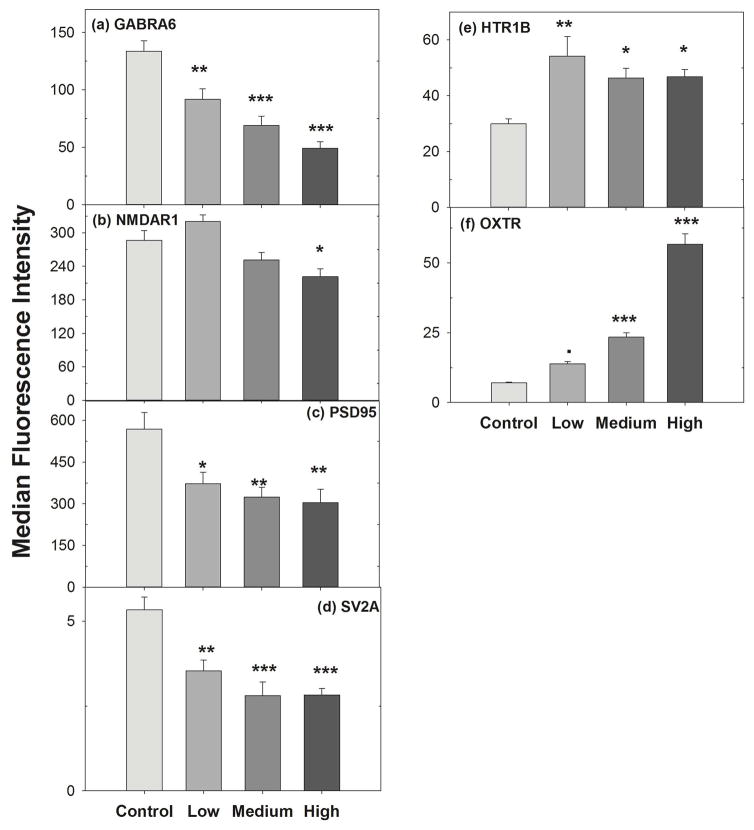

3.4 Mixture treatment (CBZ, VNX and FLX) at environmental concentration

We then sought to determine the effect of the mixture of three psychoactive pharmaceuticals (CBZ, VNX and FLX) on synaptic proteins expression at environmental concentrations. We were interested in analyzing the effect of interactions of these drugs. To accomplish this, differentiated SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells were incubated with the cocktail of carbamazepine, venlafaxine and fluoxetine in three concentrations, which were chosen based on observations in our previous fish study.

We found that HTR1B and OXTR synaptic protein expression was increased significantly at low, medium and high concentrations compared to control (Fig. 3). In contrast, mixture treatment reduced the expression of GABRA6, NMDAR1, PSD95 and SV2A synaptic proteins significantly (Fig. 3). No significant change in other (HTR2C, NCAM, GRM4 and NeuN, data not shown) synaptic protein expression was found. Data demostrated the effect of individual psychoactive pharmaceuticals at low concentrations on synpatic proteins expression, but that the mixture resulted in different results compared to either drug alone (Fig. 3), except in the case of PSD95 and OXTR.

Fig. 3. Mixture treatment on synaptic proteins expression.

Differentiated SK-N-SH cells were cultured and treated with carbamazepine, venlafaxine and fluoxetine for 48 hr. After fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), cells were incubated for 30 min at RT with primary antibodies and then incubated with Alexa488-labeled secondary antibody. The median fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry analysis. Data were analyzed using one way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons of treatments to controls. Symbols above bars indicate significant differences from the control after Dunnett’s adjustment for family-wise type I error at significance level: “***” = 0.001, “**” = 0.01, “*” = 0.05, “.” = 0.1. Error bars represent SEM.

4. Discussion

It has been found that waste-water treatment plants (WWTP) are releasing pharmaceuticals into surface water, thus producing contamination into the aquatic systems [14, 17]. Most of the isoforms of these psychoactive pharmaceuticals in WWTP are active for two reasons. First, some parts of the pharmaceuticals are not metabolized completely by clinical patients and are excreted through human liver and kidneys in an active form [17]. Second, although most of the metabolized pharmaceuticals excreted by humans are in glucuronide conjugates, which is an inactive form [17], some bacteria like Escherichia coli present in feces reconvert the inactive conjugated form into an active one (deconjugated) by secreting large amounts of an enzyme, β-glucuronidase [17].

Abnormal levels of synaptic proteins play a critical role during synaptogenesis in the etiology of ASD [3]. Due to many genetic factors such as CNV deletions, mutations, allelic exclusion, or epigenetic silencing, the expression of synaptic proteins may be altered. This alteration in the level of synaptic proteins leads to the formation of abnormal neuronal circuits, which is considered to be one of the potential mechanisms underlying ASD [3, 4]. Could psychoactive pharmaceuticals, at environmentally relevant concentrations, dysregulate the expression of key synaptic proteins that further disturb the process of synaptogenesis? To address this question, the extent to which psychoactive pharmaceuticals altered the expression of specific synaptic proteins (whose expression was found to be altered in our previous study) in a differentiated human neuroblastoma cell line was examined. As predicted, key synaptic proteins exposed to pharmaceutical treatment at environmental concentrations were significantly dysregulated compared to control (no treatment).

To study a concentration effect of these psychoactive pharmaceuticals in the present study, cell cultures were incubated with 10-fold lower and 100-fold higher than the medium concentration range. The medium concentration range of pharmaceuticals used in the present study was taken from the previous published study in our laboratory [13]. Interestingly, it was observed that carbamazepine and venlafaxine reduced the expression of synaptic proteins (NMDAR1, OXTR, HTR1B, HTR2C, PSD95, SV2A) significantly at all concentrations, including the lowest. Considering our results in vitro, and given existing knowledge of the effects of psychoactive pharmaceuticals on developmental brain, it seems conceivable that psychoactive pharmaceuticals at low concentrations might interact with common genetic variants, to produce abnormal levels of synaptic proteins and this might contribute to ASD [2, 7, 18].

Carbamazepine (CBZ) is an anticonvulsant used as an antidepressant to treat bipolar disorders [29]. CBZ blocks sodium channels, thus inhibiting the epileptic effects in the brain [29]. Fluoxetine (FLX) is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), which blocks reuptake of 5-HT [30]. VNX (SNRI) inhibits 5-HT reuptake at lower concentrations, while it blocks noradrenaline effects at higher concentrations [30]. CBZ, FLX and VNX were detected at low concentrations in surface waters of the United States [13], and were eventually found in groundwater [14]. In our study, CBZ, VNX individually and in mixtures at environmental concentrations altered in vitro expression of synaptic proteins, similar to previous results in fathead minnow brains [13].

CBZ, VNX and mixture treatments (CBZ, VNX, FLX) decreased expression of PSD95 and increased OXTR expression significantly, which is consistent with expression patterns observed in fish brain [13]. PSD95 protein was found to be associated with ASD in a recent study [22], which suggests that alteration of PSD95 expression due to psychoactive pharmaceutical treatment could be a possible mechanism in etiology of ASD. It is unclear how psychoactive pharmaceutical treatment increases OXTR expression, but other studies found that oxytocin might regulate the release of serotonin by activating oxytocin receptors, thus mediating the anxiolytic effect of oxytocin [31]. In our study, we observed that the mixture treatment of psychoactive pharmaceuticals (CBZ, FLX and VNX) increased the protein expression of OXTR, but decreased the mRNA expression of OXTR gene in differentiated SK-N-SH cells in our previous study [20]. This interesting observation suggested the involvement of a regulatory mechanism like microRNAs. MicroRNAs are small (22–23 nucleotides) [32, 33], endogenous and act as potent biological regulators of translation [34]. Several recent studies have also found that microRNAs have a key role in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [34–36].

Both CBZ and VNX individual treatments decreased the expression of HTR1B, similar to their effect in fish brain [13]. This might indicate a process of desensitization of post-synaptic receptors noted in other studies [37]. Similar to our previous fish studies, HTR2C expression was also decreased by CBZ treatment. Interestingly, increased NMDAR1 expression due to CBZ treatment was also found in fish brains [13]. Similar studies also found a significant increase in NR2A and NR2B subunits of NMDA receptors on treatment with valproate, which is also an anticonvulsant like CBZ [38].

However, mixture treatment resulted in a different outcome with respect to HTR1B and NMDAR1 synaptic proteins compared to both the fish study and individual CBZ or VNX treatments in this study. A significant decrease of inhibitory GABRA6 protein was found after mixture treatment, which is again opposite to our results in fish brains. It is unclear how mixture treatment of these pharmaceuticals produced different results than individual treatments and the fish study, but it is conceivable that psychoactive pharmaceuticals might interact with each other. The interaction between their active metabolites may have altered cell adhesion molecules (key organizers) which further altered the expression of glutaminergic and inhibitory receptors that further changed synaptic plasticity [3].

In our study, SK-N-SH cell line was selected as our model because this cell line is fast-growing, and differentiation of this cell line results in a mixture of different neuronal cells. Using Retinoic Acid (RA), these cells differentiate into more neuronal cells, which was validated by neuronal cell markers (NeuN, PSD95 and NCAM) [23, 26]. We would stress that, in the present study, observations were made on a cells from a cell line in vitro, which can differ in important ways from neurons in vivo. In the future, primary neurons may prove valuable to gain more insights into the mechanisms underlying psychoactive pharmaceutical-induced changes in syanptic proteins. Knowing the source of primary neurons from a specific part of brain, localized effects of psychoactive pharmaceuticals on that particular neuronal population might be evaluated. These future experiments may provide more insights regarding psychoactive pharmaceuticals in dysregulating synaptic proteins associated with ASD.

In this in vitro study, we found that psychoactive pharmaceuticals at low concentrations (in ppb) altered the expression of synaptic proteins, which were previously found to be associated with ASD. Data suggest that environmental contaminants like psychoactive pharmaceuticals might change the neuronal connections inside the developing embryonic brain by dysregulating the key synaptic proteins expression.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Psychoactive pharmaceuticals have been detected at low concentrations (in ppb) in wastewater, streams and drinking water.

Autism-associated synaptic proteins were significantly up- and down-regulated by psychoactive pharmaceuticals at low concentrations.

Psychoactive pharmaceuticals at environmental concentrations may contribute to the etiology of idiopathic autism by disturbing the process of synaptogenesis at early developmental stages.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the late Dr. Chris Cretekos and thank him for supporting and providing methodological and intellectual expertise to the present study, and we dedicate this publication to his memory. The project was supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant #P20GM103408.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Blumberg SJ, Bramlett MD, Kogan MD, Schieve LA, Jones JR, Lu MC. Changes in Prevalence of Parent-reported Autism Spectrum Disorder in School-aged U.S. Children: 2007 to 2011–2012. National health statistics reports. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geschwind DH. Autism: Many Genes, Common Pathways? Cell. 2008;135(3):391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datta P, Ayan B, Ozbolat IT. Bioprinting for vascular and vascularized tissue biofabrication. Acta Biomaterialia. 2017;51:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gompers AL, Su-Feher L, Ellegood J, Copping NA, Riyadh MA, Stradleigh TW, Pride MC, Schaffler MD, Wade AA, Catta-Preta R, et al. Germline Chd8 haploinsufficiency alters brain development in mouse. Nature Neuroscience. 2017;20(8):1062. doi: 10.1038/nn.4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gompers AL, Su-Feher L, Ellegood J, Stradleigh TW, Zdilar I, Copping NA, Pride MC, Schaffler MD, Riyadh MA, Kaushik G, et al. Heterozygous mutation to Chd8 causes macrocephaly and widespread alteration of neurodevelopmental transcriptional networks in mouse. bioRxiv. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaushik G, Zarbalis KS. Prenatal Neurogenesis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2016:4. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2016.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geschwind DH. Genetics of autism spectrum disorders. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2011;15(9):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landrigan PJ, Lambertini L, Birnbaum LS. A Research Strategy to Discover the Environmental Causes of Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disabilities. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120(7) doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrigan PJ. What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2010;22(2):219–225. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328336eb9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaushik G, Huber DP, Aho K, Finney B, Bearden S, Zarbalis KS, Thomas MA. Maternal exposure to carbamazepine at environmental concentrations can cross intestinal and placental barriers. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2016;474(2):291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.04.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.State MW, Levitt P. The conundrums of understanding genetic risks for autism spectrum disorders. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14(12) doi: 10.1038/nn.2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redshaw CH, Stahl-Timmins WM, Fleming LE, Davidson I, Depledge MH. Potential Changes in Disease Patterns and Pharmaceutical Use in Response to Climate Change. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health-Part B-Critical Reviews. 2013;16(5):285–320. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2013.802265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas MA, Joshi PP, Klaper RD. Gene-class analysis of expression patterns induced by psychoactive pharmaceutical exposure in fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) indicates induction of neuronal systems. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C-Toxicology & Pharmacology. 2012;155(1) doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas MA, Klaper RD. Psychoactive Pharmaceuticals Induce Fish Gene Expression Profiles Associated with Human Idiopathic Autism. Plos One. 2012;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melvin SD, Cameron MC, Lanctot CM. Individual and Mixture Toxicity of Pharmaceuticals Naproxen, Carbamazepine, and Sulfamethoxazole to Australian Striped Marsh Frog Tadpoles (Limnodynastes peronii) Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health-Part a-Current Issues. 2014;77(6):337–345. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2013.865107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mennigen JA, Stroud P, Zamora JM, Moon TW, Trudeau VL. PHARMACEUTICALS AS NEUROENDOCRINE DISRUPTORS: LESSONS LEARNED FROM FISH ON PROZAC. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health-Part B-Critical Reviews. 2011;14(5–7):387–412. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.578559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calisto V, Esteves VI. Psychiatric pharmaceuticals in the environment. Chemosphere. 2009;77(10):1257–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toro R, Konyukh M, Delorme R, Leblond C, Chaste P, Fauchereau F, Coleman M, Leboyer M, Gillberg C, Bourgeron T. Key role for gene dosage and synaptic homeostasis in autism spectrum disorders. Trends in Genetics. 2010;26(8):363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaushik G, Thomas MA, Aho KA. Psychoactive pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants may disrupt highly inter-connected nodes in an Autism-associated protein-protein interaction network. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2015:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-16-S7-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaushik G, Xia Y, Yang LB, Thomas MA. Psychoactive pharmaceuticals at environmental concentrations induce in vitro gene expression associated with neurological disorders. Bmc Genomics. 2016:17. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2784-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baudouin SJ, Gaudias J, Gerharz S, Hatstatt L, Zhou K, Punnakkal P, Tanaka KF, Spooren W, Hen R, De Zeeuw CI, et al. Shared synaptic pathophysiology in syndromic and nonsyndromic rodent models of autism. Science. 2012 Oct 5;338:128–132. doi: 10.1126/science.1224159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh A, Michalon A, Lindemann L, Fontoura P, Santarelli L. Drug discovery for autism spectrum disorder: challenges and opportunities. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2013;12(10):777–790. doi: 10.1038/nrd4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain P, Cerone MA, LeBlanc AC, Autexier C. Telomerase and neuronal marker status of differentiated NT2 and SK-N-SH human neuronal cells and primary human neurons. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2007;85(1):83–89. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PNP, HS, LN, GH, VL, WS Neuronal cell differentiation of human neuroblastoma cells by retinoic acid plus herbimycin A. Cancer Research. 1988 Nov 15;48:6530–6534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cope G, Kaushik G, O’Sullivan SM, Healy V. Gamma-melanocyte stimulating hormone regulates the expression and cellular localization of epithelial sodium channel in inner medullary collecting duct cells. Peptides. 2013;47:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pizzi M, Boroni F, Bianchetti A, Moraitis C, Sarnico I, Benarese M, Goffi F, Valerio A, Spano P. Expression of functional NR1/NR2B-type NMDA receptors in neuronally differentiated SK-N-SH human cell line. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;16(12):2342–2350. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones LJ, Gray M, Yue ST, Haugland RP, Singer VL. Sensitive determination of cell number using the CyQUANT (R) cell proliferation assay. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2001;254(1–2):85–98. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pacheco R, Ciruela F, Casado V, Mallol J, Gallart T, Lluis C, Franco R. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors mediate a dual role of glutamate in T cell activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(32):33352–33358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hough CJ, Irwin RP, Gao XM, Rogawski MA, Chuang DM. Carbamazepine inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate-evoked calcium influx in rat cerebellar granule cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1996;276(1):143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vidal R, Valdizan EM, Vilaro MT, Pazos A, Castro E. Reduced signal transduction by 5-HT4 receptors after long-term venlafaxine treatment in rats. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;161(3):695–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida M, Takayanagi Y, Inoue K, Kimura T, Young LJ, Onaka T, Nishimori K. Evidence That Oxytocin Exerts Anxiolytic Effects via Oxytocin Receptor Expressed in Serotonergic Neurons in Mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(7):2259–2271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5593-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobert O. Gene Regulation by Transcription Factors and MicroRNAs. Science. 2008;319(5871):1785–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1151651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia W, Cao GJ, Shao NS. Progress in miRNA target prediction and identification. Science in China Series C-Life Sciences. 2009;52(12):1123–1130. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson PT, Wang WX, Rajeev BW. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Pathology. 2008;18(1):130–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breving K, Esquela-Kerscher A. The complexities of microRNA regulation: mirandering around the rules. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2010;42(8):1316–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forero DA, van der Ven K, Callaerts P, Del-Favero J. miRNA Genes and the Brain: Implications for Psychiatric Disorders. Human Mutation. 2010;31(11):1195–1204. doi: 10.1002/humu.21344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raap DK, Van de Kar LD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and neuroendocrine function. Life Sciences. 1999;65(12):1217–1235. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rinaldi T, Kulangara K, Antoniello K, Markram H. Elevated NMDA receptor levels and enhanced postsynaptic long-term potentiation induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(33):13501–13506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704391104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.