Abstract

As ENT inhibitors including dilazep have shown efficacy improving oHSV1 targeted oncolytic cancer therapy, a series of dilazep analogues was synthesized and biologically evaluated to examine both ENT1 and ENT2 inhibition. The central diamine core, alkyl chains, ester linkage and substituents on the phenyl ring were all varied. Compounds were screened against ENT1 and ENT2 using a radio-ligand cell-based assay. Dilazep and analogues with minor structural changes are potent and selective ENT1 inhibitors. No selective ENT2 inhibitors were found, although some analogues were more potent against ENT2 than the parent dilazep.

Keywords: Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporters (ENTs), hENT1, hENT2, rENT2, dilazep

Graphical abstract

Nucleoside transporters are trans-membrane proteins that facilitate the movement of nucleosides, nucleobases, and their analogues across the cell membrane. There are two families of transporters belonging to the solute carrier class of proteins, concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNTs) and equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs).1 Both ENTs and CNTs play a vital role in regulating the levels of nucleosides and nucleobases within the cell and interstitial space as these highly polar molecules cannot passively diffuse across cellular membranes.2, 3 Substrate specificity,4 expression levels, and location of expression vary between the two families of transporters and among the isoforms within each class,5 enabling the design of potent and selective inhibitors. Within the equilibrative family, there are four known isoforms in humans: hENT1, hENT2, hENT3, and hENT4.6 Human ENT3 is an intracellular transporter and hENT4 has limited expression, functioning as an adenosine transporter only under acidic conditions,7 whereas hENT1 and hENT2 are widely expressed throughout the body.6

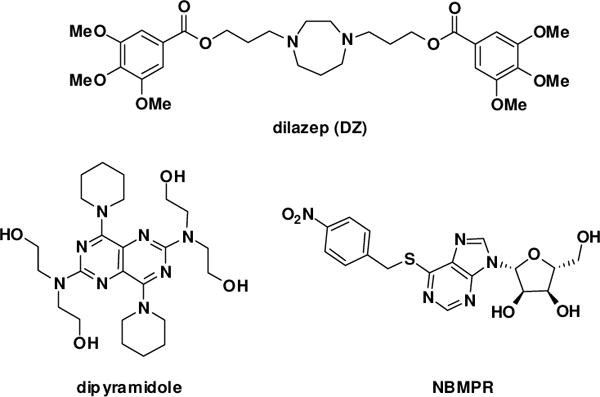

While hENT1 and hENT2 share greater than 75% sequence identity to their rodent homologues, the human isoforms are only 46% related.7 Both hENT1 and hENT2 have broad permeant selectivity, transporting both pyrimidine and purine nucleosides, but hENT2 transports nucleobases as well and is insensitive to the nucleoside transport inhibitor S-(4-nitrobenzyl)-6-thioinosine (NBMPR).6 Likewise, hENT1 and hENT2 possess different Ki values with regard to dipyridamole and dilazep, two potent nucleoside transporter inhibitors which are also approved pharmacologic agents (Figure 1).8 For each of these inhibitors, hENT1 shows a significantly greater sensitivity to inhibition.

Figure 1.

Inhibitors of ENT1 and ENT2

There are a number of potential therapeutic uses for nucleoside transporter inhibitors. Studies have shown a correlation between nucleoside transporter inhibition, specifically hENT1, and reduction in cellular damage from acute ischemia via effects on tissue adenosine levels.10 Cancer chemotherapy is another area of potential therapeutic application, especially as a number of current drugs are transported by nucleoside transporters.11 The current study was prompted as a result of a collaborative project, which showed that ENT inhibitors potentiated the activity of oncolytic herpes simplex I virus (oHSV1) in killing cancer cells.12 Oncolytic viruses are a treatment that selectively targets cancer cells. Genetically engineered viral vectors spare normal cells, mitigating collateral damage from normal cancer chemotherapy. However, because oHSV1 has limited replication and spread to neighboring cancer cells, its potential uses have been limited.13 Prior work showed that the efficacy of oHSV1 treatment could be improved with the addition of appropriate pharmaceuticals.14 A high-throughput screen identified dipyridamole and dilazep, two FDA-approved drugs that are ENT1 and ENT2 inhibitors (Figure 1), as efficacious molecules for increasing the activity of oHSV1.12 The two drugs are both anti-platelet drugs that act through phosphodiesterase (PDE) and protein kinase (PK) inhibition. However, experiments indicated that the mechanism of action for oHSV1 activity improvement did not involve these mechanisms, but rather directly involved hENT1 inhibition, as NBMPR (Figure 1), a known potent ENT1 inhibitor demonstrated similar results, while PDE and PK inhibitors did not.13 While both drugs are potent hENT1 inhibitors, at therapeutic levels hENT2 inhibition may occur. To advance our understanding of how nucleoside transporter inhibitors can improve oHSV1 or other similar therapies, potent selective inhibitors are needed. As such, dilazep was used as a starting point to synthesize analogues to explore the structure-activity relationship (SAR) with respect to ENT1 and ENT2 selectivity.

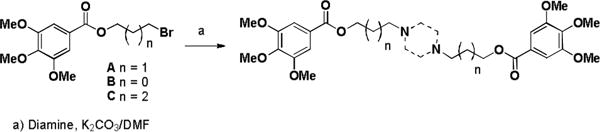

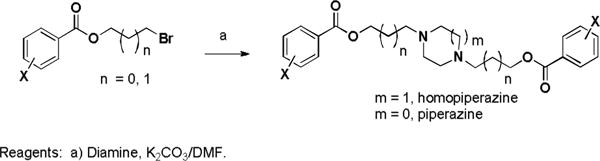

Dilazep (DZ) analogues were synthesized by varying the substituents on the phenyl rings, the functional group connecting them to alkyl linkers of varying length, and the central cyclic diamine. Three bromoalkyl 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl esters were treated with various cyclic diamines to make symmetric compounds (Scheme 1). Attempts to make the acyclic analogue by treating 1 with N,N′-dimethylethylene diamine were unsuccessful.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of symmetrical dilazep analogues

Unsymmetric analogues were prepared. Alkylation of mono t-BOC-homopiperazine with bromoester A followed by TFA deprotection produced compound 12 which was alkylated with bromoester B or C to give compounds 13 and 14, respectively (Scheme 2). Compound 12 was acylated to give compounds 15 and 16, respectively. Lower molecular weight analogues were prepared by treating A and B with either methyl- or benzylhomopiperazine, methylpiperazine, pyrrolidine, and morpholine.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of unsymmetrical analogues

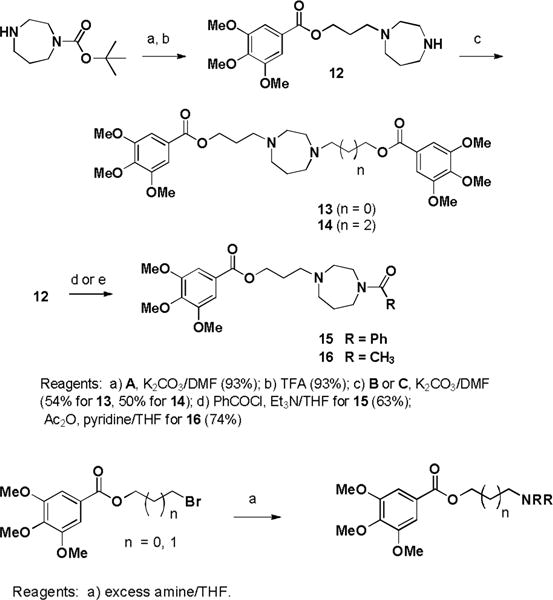

Analogues were next prepared removing one, two, or all three methoxy groups from the phenyl rings, and by adding an electron withdrawing fluorine substituent (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Substitutions on phenyl rings

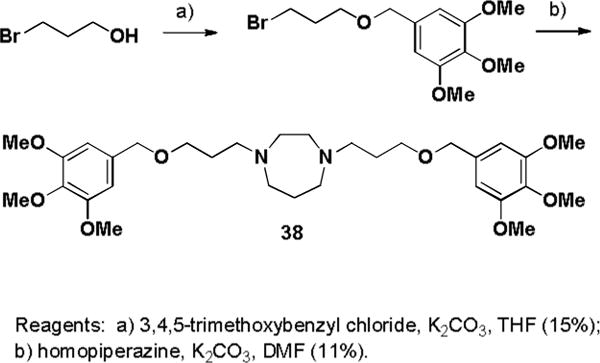

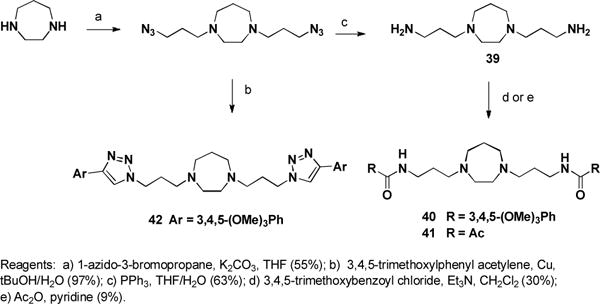

The ester groups of dilazep were replaced with an ether, amide, or heterocycle. 3-Bromo-1-propanol was alkylated with 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzyl chloride and the ether product was treated with homopiperazine to yield 38 (Scheme 4). Bis-alkylation of homopiperazine with 3-azido-1-bromopropane followed by Staudinger reduction gave diamine 39. Treating the diamine with 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzyl chloride failed to cleanly produce the desired amino-linked compound, but treatment of the bis-amine with 3,4,5-trimethoxy benzoyl chloride or acetic anhydride gave the desired bis-amides 40 and 41 respectively (Scheme 5). Copper catalyzed cycloaddition of the bis-azide intermediate with 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl acetylene gave the heterocyclic linked analogue 42.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of dilazep ether analogue

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of dilazep amide and heterocyclic analogue

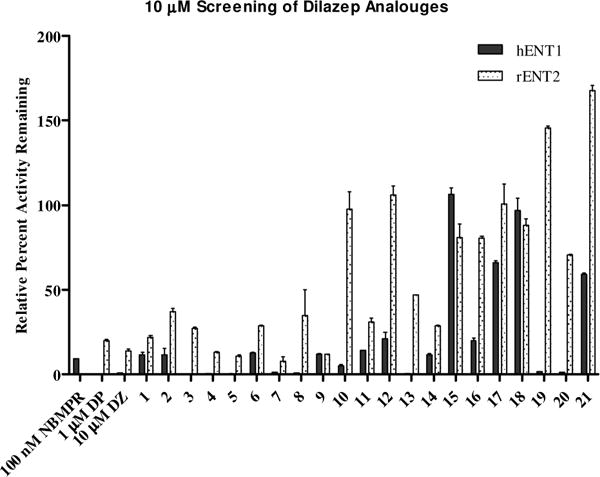

Compounds were tested in duplicate at 10 μM in a forty-eight well plate cell-based radio-ligand uptake assay, using previously established transgenic PK15NTD porcine cells expressing individual recombinant human (h) ENT,13 and H9c2 rat cells expressing native rENT2, using dilazep, dipyramidole and NBMPR as reference compounds (Figures 2–3). For the rat cells, rENT1 was inhibited with 100 nM NBMPR prior to addition of compounds to avoid participation of the low level ENT1 expressed by these cells. Decreased uptake of the 3H[5-]uridine indicated a “hit” and was confirmed by repeating the assay with seven concentrations serially diluted over at least four log units in order to establish dose-response curves (Table 4). These assays were run in triplicate. Ten compounds were tested in dose-response assays against ENT1, five of these were also tested for dose-response (Table 4) against rENT2 based upon their activity at 10 μM.

Figure 2.

10μM Screen of dilazep analogues 1–21. Data presented as average percent relative uptake to control untreated cells. Error bars are the standard deviation from the mean.

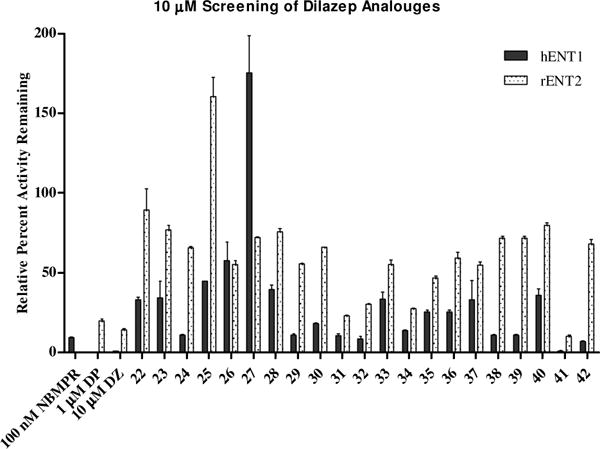

Figure 3.

10 μM Screen of dilazep analogues 22–42. Data presented as average percent relative uptake to control untreated cells. Error bars are the standard deviation from the mean.

Table 4.

Selected IC50s with 95% CI of dilazep analogues

| Compound | hENT1 IC50 [nM] (95% CI) |

rENT2 IC50 [nM] (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| DZ | 17.5 (9.4–33.8) |

8 800 (2070–37300) |

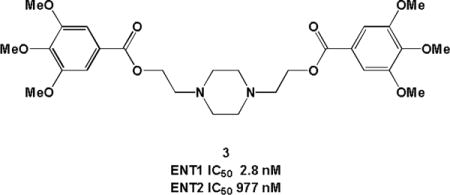

| 3 | 2.8 (1.6–4.7) |

977 (598–1690) |

| 4 | 66.1 (35.7–122) |

1310 (898–1910) |

| 5 | 17.7 (12.8–25.7) |

1080 (643–1800) |

| 7 | 3.2 (1.7–6.2) |

1490 (843–2630) |

| 8 | 31.0 (13.4–71.7) |

NAa |

| 13 | 4.6 (2.5–8.6) |

NA |

| 15 | 803 (503–1280) |

NA |

| 20 | 217 (112–419) |

NA |

| 40 | 93.9 (27.9–316) |

NA |

NA = Insignificant rENT2 inhibitory activity

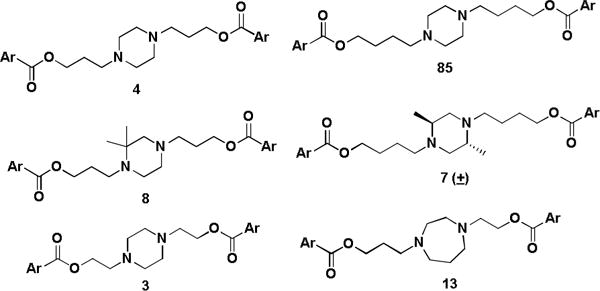

Dilazep and close analogues are potent hENT1 inhibitors (IC50 < 100 nM) with little or no activity against rENT2. The central homopiperazine ring can be replaced with a piperazine, or methyl-substitued piperazine. The alkyl chains can be extended or shortened by one carbon with little change in potency. When the ester bonds of DZ were replaced with an ether or heterocycle, hENT1 activity was diminished, but activity was observed with the corresponding amide (40). Compounds with the 3,4,5-(OMe)3 substituted phenyl rings displayed activity (Figure 4), though two of these groups are not required based upon the activities of 15 and 20.

Figure 4.

Structures of hENT1 active compounds (Ar = 3,4,5-(OMe)3Ph)

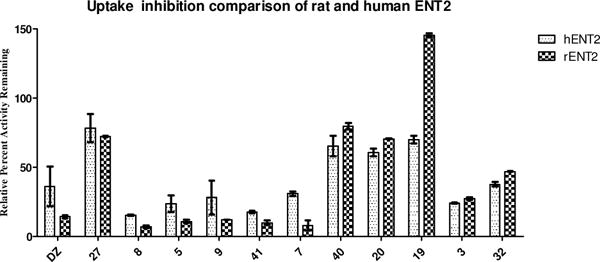

No potent rENT2 inhibitors were found, though compounds 3 and 5 have IC50s ca. 1 μM. Selected compounds demonstrating activity against rENT2 were cross-screened against hENT2 (Figure 5). Only minor differences in activities were observed between the two assays with the compounds tested.

Figure 5.

Species comparison of hENT2 and rENT2 screening data. Data presented as average percent relative uptake to control untreated cells for duplicate wells.

Given these results, the activity previously reported on the efficacy of oHSV1 treatment in the presence of dilazep is most likely due solely to ENT1 and not ENT2 inhibition.12 Further studies with oHSV1 and the compounds described here support this hypothesis, results of these studies will be reported shortly. Other chemical scaffolds will need to be explored to discover potent and selective inhibitors of ENT2 to ascertain more about the role and importance of this transporter. oHSV therapy of cancer has now advanced to phase 3 clinical trials.15 There is an urgent need to evaluate and utilize therapeutics that will enhance oHSV efficacy. Further studies of dilazap analogues should be considered in appropriate animal cancer models with the aim of progressing to clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Scheme 1 Analogues

| Compound | n | Diamine |

|---|---|---|

| DZ | 1 | Homopiperazine |

| 1 | 0 | Homopiperazine |

| 2 | 2 | Homopiperazine |

| 3 | 0 | Piperazine |

| 4 | 1 | Piperazine |

| 5 | 2 | Piperazine |

| 6 | 1 | 2,5-Dimethylpiperazine (±) |

| 7 | 2 | 2,5-Dimethylpiperazine (±) |

| 8 | 1 | 2,2-Dimethylpiperazine |

| 9 | 2 | 2,2-Dimethylpiperazine |

| 10 | 1 | 2,5-Diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (±) |

| 11 | 2 | 2,5-Diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (±) |

Table 2.

Scheme 2 Analogues

| Compound | n | Amine |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 0 | N-Methylhomopiperazine |

| 18 | 1 | N-Methylhomopiperazine |

| 19 | 0 | N-Benzylhomopiperazine |

| 20 | 1 | N-Benzylhomopiperazine |

| 21 | 0 | N-Methylpiperazine |

| 22 | 1 | N-Methylpiperazine |

| 23 | 0 | Pyrrolidine |

| 24 | 1 | Pyrrolidine |

| 25 | 0 | Morpholine |

| 26 | 1 | Morpholine |

Table 3.

Scheme 3 Analogues

| Compound | n | m | Diamine | X |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 1 | 2 | Homopiperazine | H |

| 28 | 1 | 1 | Piperazine | H |

| 29 | 0 | 2 | Homopiperazine | 4-OMe |

| 30 | 1 | 2 | Homopiperazine | 4-OMe |

| 31 | 1 | 1 | Piperazine | 4-OMe |

| 32 | 0 | 1 | Piperazine | 4-OMe |

| 33 | 0 | 2 | Homopiperazine | 3,5-(OMe)2 |

| 34 | 1 | 1 | Piperazine | 3,5-(OMe)2 |

| 35 | 1 | 1 | Piperazine | 3,5-(OMe)2 |

| 36 | 1 | 2 | Homopiperazine | 4-F |

| 37 | 1 | 1 | Piperazine | 4-F |

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the NIH-MLPCN program (1 U54 HG005032-1 awarded to S.L.S.) as well as NIH RO1GM10405 (J.K.B.) and grant RO1CA102139 (R.L.M.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Material

Chemistry experimental procedures and characterization of all compounds plus biological assay details.

References

- 1.Buolamwini J. K. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 1997;4:31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acimovic Y, Coe I. R Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastor-Anglada M, Cano-Soldado P, Errasti-Murugarren E, Casado FJ. Xenobiotica. 2008;38:972. doi: 10.1080/00498250802069096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyde RJ, Cass CE, Young JD, Baldwin SA. Mol Membr Biol. 2001;18:53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennycooke M, Chaudary N, Shuralyova I, Zhang Y, Coe I. R Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:951. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin SA, Beal PR, Yao SYM, King AE, CassC E, Young JD. Eur J Physiol. 2004;441:8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young JD, Yao SYM, Sun L, Cass CE, Baldwin SA. Xenobiotica. 2008;38:995. doi: 10.1080/00498250801927427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffith DA, Jarvis SM. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta Trop. 1996;1286:28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(96)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ely SW, Berne RM. Circulation. 1992;85:893. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grenz A, Bauerle JD, Dalton JLH, Ridyard D, Badulak A, Tak E, et al. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122:18. doi: 10.1172/JCI60214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Zhang J, Visser F, King KM, Baldwin SA, Young JD, Cass CE. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:85. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passer BJ, Cheema T, Zhou B, et al. Cancer Research. 2010;70:7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Pimple S, Buolamwini JK. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:307. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheema TA, Kanai R, Kim GW, Wakimoto H, Passer B, Rabkin SD, Martuza RL. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman HL, Bines SD. Future Oncol. 2010;6:941. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.