Abstract

In this paper we focus on how participants in peer review interactions use laughter as a resource as they publicly report divergence of evaluative positions, divergence that is typical in the give and take of joint grant evaluation. Using the framework of conversation analysis, we examine the infusion of laughter and multimodal laugh-relevant practices into sequences of talk in meetings of grant reviewers deliberating on the evaluation and scoring of high-level scientific grant applications. We focus on a recurrent sequence in these meetings, what we call the score-reporting sequence, in which the assigned reviewers first announce the preliminary scores they have assigned to the grant. We demonstrate that such sequences are routine sites for the use of laugh practices to navigate the initial moments in which divergence of opinion is made explicit. In the context of meetings convened for the purposes of peer review, laughter thus serves as a valuable resource for managing the socially delicate but institutionally required reporting of divergence and disagreement that is endemic to meetings where these types of evaluative tasks are a focal activity.

1. Introduction

Evaluative meetings are ubiquitous across business, educational, and research institutions. These are meetings in which participants with special professional expertise are charged with the task of reviewing and collaboratively evaluating a set of materials, with the resulting evaluations being used to support institutional decisions regarding the distribution of grades, admissions or hiring decisions, or, as we consider here, grant funding. Interactional research on evaluative meetings has included guild admission meetings (McKinlay & McVittie, 2006), academic curriculum proposal meetings (Barnes, 2007), and teaching-team meetings for evaluating student achievement documents (Mazeland & Berenst, 2008), among other contexts. Whether evaluating applicants for admission to an organization or for rank and achievement, the consequences of such meetings are far-reaching. The current paper reports on findings from the close examination of one specific form of evaluative meeting, in which expert scientists review applications for large federally-funded research grants, with such funding playing a major role in the career advancement for academic researchers.

Despite the ubiquity of such meetings and the significant influence they have on the distribution of substantial amounts of research funding, their moment-to-moment interactional dynamics have remained largely unexamined. Research on grant peer review panel interactions has almost exclusively relied on ethnographic interviews and participant observation (Ahlqvist et al, 2013; Lamont, 2009) rather than close analysis of unfolding interaction. Indeed, research directly examining discourse and interaction in review panel meetings has only recently emerged (Gallo, Carpenter, & Glisson, 2013; Pier, Raclaw, Kaatz, Carnes, Nathan, & Ford, 2017; Authors, 2015). As part of a larger project aimed at documenting interactional practices inside the “black box” of peer review meetings,1 in this paper we focus on how participants in these settings use laughter as a resource to manage the divergence of evaluative positions that characterizes the give and take of joint grant evaluation. Using the framework of conversation analysis, we examine the infusion of laughter and multimodal laugh-relevant practices (Ford & Fox, 2010) into episodes of naturally-unfolding interaction taken from panel meetings of grant reviewers, meetings following the norms and practices used by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). We focus on a recurrent sequence in these meetings, what we call the score-reporting sequence, a sequence type that is a frequent location in our data for the introduction of laugh-relevant practices.

In the sections that follow we introduce the score-reporting sequence and examine how and why the recurrent activity of reporting preliminary scores emerges as a locus for laugh-relevant practices.

2. Data, Methods, and the “Score-Reporting Sequence”

The analysis draws from a database of three meetings convened for the purposes of peer review; the focal task of these meetings was joint evaluation of high-level scientific research grant proposals. Each panel consisted of 10–12 reviewers who were assigned a set of six real but anonymized grant applications for NIH Research Project Grants, also known as R01 grants. Each panel reviewed grant applications that had originally been submitted to NIH’s National Cancer Institute. All reviewers were experts in their respective fields of oncology research at varying stages of their research careers, and all had previously received R01 grants, an NIH requirement for serving as an R01 reviewer.2 After individually evaluating the applications and sharing their evaluations through a web portal, panelists representing research institutions throughout the US, traveled to a major US city and assembled in a meeting room to review the applications. Each meeting, videotaped from three camera angles, lasted from 2:53 to 3:37, totaling approximately 10 hours of meeting interaction. Interactions were recorded with full informed consent of participants, and permission to publish transcripts and still images from these interactions was obtained from all participants. The video data were transcribed using the conventions of conversation analysis (Hepburn & Bolden, 2013), with notations of embodied actions relevant to the analysis at hand.

In addition to the reviewers, meetings were attended by a Scientific Review Officer (SRO) who served as the primary coordinator for the pre-meeting review process, including the selection of a meeting chair and co-chair from among the reviewers. In concert with the chairperson, the SRO oversaw the running of the panel meeting itself. Prior to the meeting, reviewers were responsible for writing critiques detailing the strengths and weaknesses of their assigned applications and for arriving at preliminary scores for the overall impact of the application as well as for specific review criteria. Reviewers scored applications using a reverse nine-point scale, with one corresponding to “Exceptional” and nine corresponding to “Poor.”3 Each reviewer’s preliminary scores and critiques were made accessible to other panelists through an online review site. In the days leading up to the in-person meeting, this site allowed reviewers to gain a general sense of whether a grant application had been evaluated favorably by its three assigned reviewers.4

The overall impact scores and critiques for each application are also made interactionally consequential during the meeting itself, particularly during the early moments of each application’s review, when the preliminary scores are announced by each reviewer. We turn now to examining how the announcements of preliminary scores in particular are treated within the review meeting during a recurrent and predictable sequence type: the score-reporting sequence. It is in this initial reporting phase of the meeting that we find evidence that participants treat score divergence as accountable, delicate, worthy of mitigation, and potentially laughable.

The score-reporting sequence routinely unfolds at the beginning of the panel’s review of each grant application. The sequence consists of three parts: (1) the Chairperson’s request for the reviewers’ preliminary scores, (2) the reviewers’ individual score reports, and (3) the Chairperson’s summarization of the score range. Treatment of a divergent score as laughable may be initiated by a reviewer, by another panelist, or by the chair, and may be occur during the announcement of individual scores or during the Chair’s summary. Because of the variation in where and by whom laugh practices are initiated, it useful to differentiate between the target of the laughable and the position where they are first so treated.

Our first look at laughter in a score-reporting sequence is in Excerpt 1, below. The Chair announces the title of the application to be discussed and lists the names of the three panelists designated as primary, secondary, and tertiary.5 The reporting sequence proper begins as the Chair requests the reviewers’ preliminary scores at line 10. (For ease of identification, here and in other excerpts, we underline the abbreviations of those reviewers’ names: for Excerpt 1 these are Joshi, Vitantonio, and Patil.)

(1) Not So Good (Henry 2–6)

At line 17 the Chair formulates an assessment of the score range as featuring two “good” scores (i.e., the scores of two assigned by the primary and secondary reviewers). Following a pause in the Chair’s turn, the primary reviewer (Joshi) collaboratively completes (Lerner, 1991, 2013) the assessment, describing the score of the tertiary reviewer (Patil) as “not so good.” This contrastive formulation of the score range highlights the divergence in the reviewers’ scores, while the collaborative production of this action between the Chair and primary reviewer also introduces a surprise, a twist to the normal expectations for how this action should proceed. Both contrasts and counter-to-expectation actions are routinely heard as laughables (Drew, 1987; Ford & Fox, 2011; Glenn, 2003; Jefferson, 1979), and this understanding of the score range is supported by the initial laughter from another panelist (Attar, line 20) and the subsequent smiles shared between the assigned reviewers and another panelist (Ramachandran, lines 21–24). Here, then, we see a first instance of what we further explore in this paper: The divergence in reviewer scores is treated as a laughable.

In each of the cases examined here, we focus specifically on divergence in the score range as occasioning shared laughter from the group. This orientation to score divergence as the target of laughter can be clearly seen in Excerpt 2, taken from a review of a grant from an applicant whose last name is “Lopez” (pseudonym). The primary reviewer, Anwar, has assigned the application a score of three, while the secondary reviewer, Basso, has assigned the application a perfect score of one.

(2) How Much Diversity (Lopez 6–21)

Following the delivery of the reviewers’ score reports, both the primary reviewer (Anwar) and the tertiary reviewer (Basso) display an orientation to their divergence in scores as accountable: At line 23 Anwar acknowledges Basso’s score report, and the acknowledgement is produced with high onset, possibly displaying a stance of surprise that may contribute to making the divergence accountable. At line 25 Basso concedes that the application was in fact “not that good,” and Anwar responds at line 26 by conceding that he “should have changed [his] score.” The exchange invites laughter and smiles from both reviewers as well as another panelist (Bhat), and it receives additional mediation from the Chair at line 32 as he frames the divergence in a more positive light, announcing that the divergence in scores “tells you how much diversity we have.” As this case illustrates, then, divergence in reviewer scores is a potentially delicate matter, and the handling of such matters may provide for the relevance of laughter-relevant practices from both the disagreeing parties and the larger panel of reviewers.

Both subtle and more explicit orientations to divergence in the score range may be treated as laughable. Additionally, the organization of laugh-relevant practices in response to these actions is sensitive to the progressivity of the score-reporting sequence: While there may be smiles, nods, and eyebrow flashes shared between individual participants during the reporting of the primary and secondary reviewers’ scores, fully shared laughter between group members is reserved for the space following the tertiary reviewer’s score report.

3. Laughter as a Resource for Managing Delicate Activities

As we look at further score-reporting sequences in which laughter figures, it is useful to note that in research on laughter in ordinary and institutional talk, the notion of delicacy has been usefully applied. The notion of a “delicate” action or activity is best understood with respect to preference organization. While interactants do considerable work to systematically avoid explicit and direct disaffiliation (Pomerantz, 1984; Pomerantz & Heritage, 2012), social life is filled with activities that push at the boundaries of social solidarity and affiliative relations. As a means of managing the delicacy of navigating through these types of activities, dispreferred actions are organized in identifiably careful ways: Speakers normatively delay the delivery of dispreferred actions and formulate these actions with hesitations and through turn shapes that mitigate and provide accounts for their production. Given the preference for affiliation as a mechanism of social solidarity, it becomes clear that, in peer review meetings, the score-reporting sequence has the potential to place designated reviewers in interactionally and interpersonally sensitive positions. Reviewers regularly need to report scores that are clearly divergent, requiring that they display public, on-record, and oftentimes unmitigated disagreement with their peers. A recurrent challenge for these reviewers, then, is how to manage the socially delicate but institutionally required reporting of divergent evaluations, made public through their preliminary score reports in the score-reporting sequence.

One well-documented means for managing socially delicate activities is to introduce laughables and laughter in the midst of, and immediately following, delicate or dispreferred actions. Laughter is regularly deployed when navigating activities that may work against the joint achievement of affiliation, as when responding to improprieties (Jefferson, Sacks, & Schegloff, 1987), displaying resistance to troubles (Jefferson, 1984),6 defusing complaints (Holt, 2012), and otherwise modulating problematic courses of action (Potter & Hepburn, 2010). This observation holds for talk in both ordinary conversation and institutional contexts. For example, laughter has been shown to be a resource for managing episodes of conflict or opposition in such institutional environments as medical consultations (Arminen & Halonen, 2007; Fatigante & Orletti, 2013; Haakana, 2001), meetings and interviews (Glenn, 2013; Kangasharju & Nikko, 2009; Osvaldsson, 2004), and the classroom (Jacknick, 2013; Sert & Jacknick, 2015). It is not surprising, then, that in the institutional interaction of peer review, where participants must navigate between the requirement of reporting potentially divergent scores and the omni-relevant preference for pro-sociality and interpersonal affiliation, laugh-practices are deployed to diffuse the awkwardness of moments when disaffiliation is explicitly enacted through the on-record reporting of divergent scores.

In the following section we present a series of case-by-case analyses to explicate the use of laugh practices during score-reporting sequences in our peer review data. We examine two ways in which the participants in our data orient to score divergence as occasioning laughter: (1) cases in which a participant (typically the Chairperson) explicitly formulates reviewer scores as a laughable, and (2) cases in which score divergence is not presented as a laughable, yet secures laughter all the same. We begin with an analysis of the former case before examining instances of the latter.

4. Laughter in the Score-Reporting Sequence

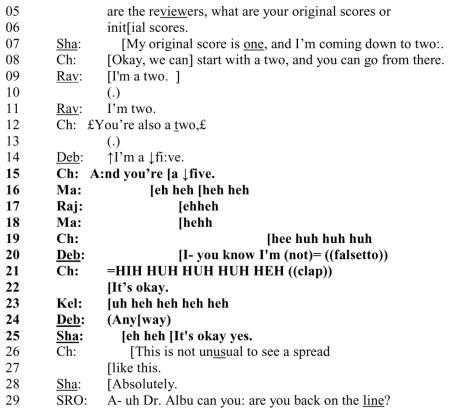

The data in Excerpt 3 is taken from a review of a grant from an applicant whose last name is “Henry”. Recall that the NIH scoring system uses a reverse nine-point scale, with one corresponding to “Exceptional” and nine corresponding to “Poor.” Prior to the meeting, the assigned reviewers posted preliminary scores of two, two, and five to the Henry application, and here they publicly announce those scores. Note that when the primary reviewer, Shan, announces his “original score” (line 7), he is referring to this preliminary score that he posted to the review website where he and others could compare scores prior to the panel meeting; Shan has elected to change his score even prior to the panel’s discussion of this application. We will focus on the actions responsive to the score report of the tertiary reviewer, Debra, at line 14:

(3) Not unusual (Henry 3–20)

The Chair begins the score-reporting sequence at lines 1–5 by naming the next application to be discussed and listing the names of the three assigned reviewers (Shan, Ravindra, and Debra). Following the Chair’s request for the reviewers’ preliminary scores at line 6, the primary and secondary reviewers announce their scores, with the Chair confirming each score as he marks them on his scoring sheet (lines 7–12).7 At line 14 the tertiary reviewer, Debra, announces that her preliminary score is five, a score that significantly contrasts with the scores reported by both the primary and secondary reviewers. It is thus evident at this point in the score-reporting sequence that there is disagreement, a divergence in expert opinions on the merits of the application.

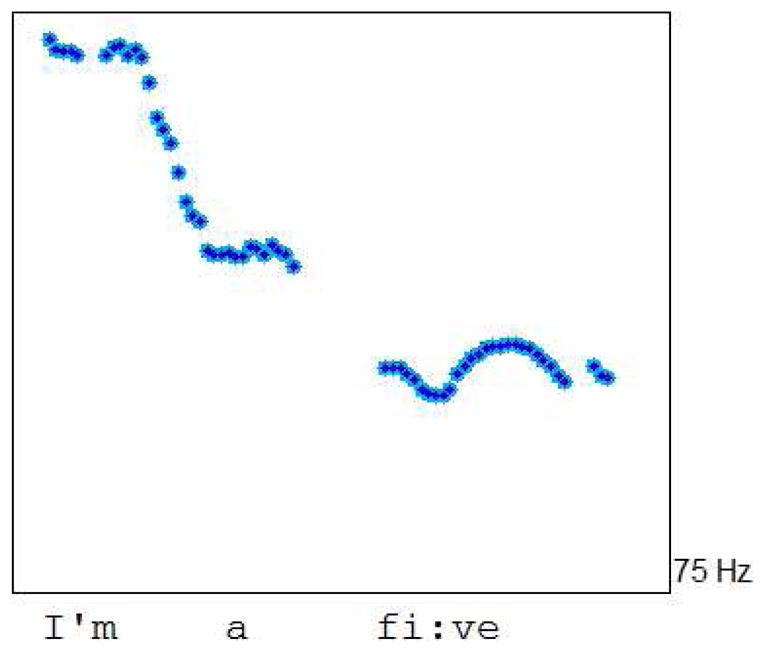

Indexing this divergence and enacting a particular stance, the tertiary reviewer, Debra, announces her score with marked phonetic delivery, employing a sharply falling intonational contour that Couper-Kuhlen (2009) has described as “subdued prosody.” Figure 1 shows a Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2016) picture of the pitch trace of this unit of talk, in which the speaker drops ~140 Hz over the course of its production. Couper-Kuhlen shows how subdued prosody may be used to register the speaker’s disappointment with a prior action, and in the present context, Debra’s turn has just such a resigned quality.

Figure 1.

Pitch trace of Debra’s score announcement: “↑I’m a ↓fi:ve”

Just prior to the review of the current application, Debra had assigned a score of five to an application that was similarly divergent, i.e., weaker, in comparison to the scores of her fellow reviewers. The delivery of her score at line 14 above may thus display recognition, and disappointed resignation, that her score report again places her in a position of disagreement relative to the other two reviewers. The Chair responds at line 15 by repeating Debra’s score, delivering this confirming action with similarly subdued prosody (though with less extreme fall in pitch).8

In matching his prosody to Debra’s, the Chair can be heard to jokingly echo or even mimic the stance that Debra has introduced through her report, perhaps displaying that he shares her resignation. By echoing Debra’s prosody, the Chair also joins in highlighting the divergence in scores, but he does so in a playful manner, making his action potentially laugh relevant and inviting laugh responses. His playful joining in with Debra’s stance also displays an orientation to Debra’s public reporting of divergence as an interactional event in need of recognition and amelioration. Prior to the completion of the Chair’s turn, but after his adoption of Debra’s prosody is evident and further projectable, other participants begin to laugh, growing to an overlapping cascade of shared responsive laugh practices in the seconds that follow. In the midst of this shared spate of laughter, both the Chair and primary reviewer (Shan) offer their acceptance of Debra’s divergence, reassuring her, at lines 22 and 25, that “It’s okay.” The Chair then moves to normalize the score divergence by assessing the score range seen here as “not unusual,” a stance with which the primary reviewer affiliates and even upgrades with “Absolutely” at line 28. These actions reflexively confirm that score divergence is treated as accountable as well as both excusable and not atypical in the context of peer review meetings. Thus, while divergence is explicitly claimed to be “not unusual,” the actions of the Chair and primary reviewer enact the apparent interactional need for resolution of what is being treated, through the laughter and the accounting itself, as a delicate moment.

Excerpt 4 is taken from a discussion of the “Lopez” application, which again features significant divergence between the assigned reviewers’ preliminary scores. This excerpt offers a clear example of the relational work that may be conducted between individual reviewers through dyadic side-exchanges of laughter and smiles even prior to the shared laughter spate that typically follows the third reviewer’s score report. Fully joining in with shared laughter is apparently reserved for a position after the third score is reported.

(4) Quite a range (Lopez 2–6)

![]()

The Chair begins the score-reporting sequence at lines 1–4 by announcing the name of the applicant and the identities of the three assigned reviewers. The Chair’s request for reviewers to report their scores (line 6) is followed by the insertion of an identification sequence at lines 8–13. After confirming her identification as the primary reviewer, Vitantonio reports a score of one for the grant (line 15). In contrast, the secondary reviewer, Patil, announces that his preliminary score is a much weaker four (line 20). Thus, by the time the secondary reviewer has announced his score, it is evident that there is significant disagreement among the reviewers. The subsequent announcement of the tertiary reviewer’s (Lin’s) score of one at line 26 positions the secondary reviewer, Patil, as the accountable party, his score of four being, as it were, the outlier.

Holding off on addressing the laugh-relevant practices initiated by another panelist (Ramachandran) at lines 22 and 27, let us begin our analysis at line 28, just following the reporting of the clearly divergent scores. Here the Chair formulates an assessment of the score range that frames it as worthy of remark, “So we ha:ve quite a range here.” As the Chair delivers this turn and extends it with the specification of “one to four,” he looks up from his notes and shifts his gaze between the three main reviewers (see lines 29–30), achieving mutual gaze with Vitantonio, the primary reviewer who assigned a score of one to the grant, and Patil, the secondary reviewer whose score was a notably weaker four. In coordination with these gaze exchanges, the Chair specifies the score range of “one to four” while visibly smiling. By remarking on the divergence of scores, and by making eye contact with and smiling at the reviewers, the Chair treats the divergence as meriting special management. The Chair’s gaze direction, his visible smiling, and the “smile voice” articulation of “four” designate these divergent reviewers as the recipients of his apparent move toward humor. The Chair’s gaze behavior and remark at line 29 receive immediate responsive smiles, shifts in gaze, and laughter from Vitantonio and Patil, the reviewers whose scores are at odds with one another. The split-second nature of these responses enacts a readiness to join in the laughter and to share the opportunity for prosociality as they exchange smiles with each other, thereby initiating their collaboration with the Chair in using laugh practices to manage the interpersonal tension of evident disagreement.

Looking back at the embodied exchanges just prior to the Chair’s articulation of the score range (lines 22–28), we see evidence that the participants not only understand score divergence as calling for delicate treatment, but may also introduce such treatment even before the Chair has done so. Consider that segment of the excerpt again:

(4) Quite a range (Lopez 2–6)

Following the Chair’s confirmation of Patil’s score at line 21, another participant, Ramachandran, shifts his gaze to Patil and smiles (line 22). Following the tertiary reviewer’s score report at line 26, which positions Patil as being in disagreement with the other assigned reviewers, Ramachandran again shifts his gaze toward Patil, now producing pursed lips and a brief eyebrow flash (line 27). For his part, Patil responds with a brief smile toward Ramachandran before turning his gaze toward the Chair in likely anticipation of the Chair’s assessment of the score range (line 28). Furthermore, as the Chair begins to articulate the score range, another participant, Amirmoez, also meets Patil’s gaze and flashes a brief smile (line 32). Notably, these fleeting embodied exchanges are exclusively dyadic, and similar side exchanges are common in other episodes of score divergence in score-reporting sequences. It is not until after the third score report and after the Chair contribute laugh practices that we find multiple parties, beyond dyads, joining in.

Excerpts 3 and 4 both illustrate the ways in which review panelists may respond to episodes of score divergence by formulating reviewer scores so as to invite laughter from the group: in Excerpt 3 this entailed the Chairperson’s playful echoing of Debra’s phonetically marked score report, while in Excerpt 4 the Chairperson actively moves the group toward laughter through a constellation of embodied practices, among them eye gaze, visible smiles, the phonetic production of talk with audible “smile voice” and the production of laughter itself. And yet as Excerpt 4 also shows, laugh-relevant practices may also accompany episodes of score divergence even when this divergence is not explicitly presented as a laughable, as with the dyadic exchange of smiles between reviewers seen at lines 21–28. Such cases also highlight the way that shared laughter and multimodal laugh-relevant practices reflexively treat the reporting of divergent scores as interactionally delicate and in need of medication.

One such case can be seen in Excerpt 5 below, taken from a discussion of the “Abel” application. Here again there is significant divergence between the assigned reviewers’ preliminary scores. The Chair begins at lines 1–4 by announcing the name of the applicant and the identities of the three assigned reviewers: Dharani, Jack, and Moreau. Following a mis-start in the review process at lines 5–7,9 at line 8 the primary reviewer (Dharanipragada) reports a score of two for the application.

(5) On the fence (Abel 6–12)

![]()

At lines 11–13, as the Chair confirms the primary reviewer’s (Dharanipragada’s) score, the secondary reviewer, Jack—having originally submitted a weaker written score of three—responds to Dharanipragada’s score announcement with an audible and embodied stance display: Jack visibly deflates (Clifton, 2014) as he slumps down in his chair and he tightens his lips in a grimace while producing an audible outbreath, a configuration of semiotic resources recognizable as a sigh (Hoey, 2014). The organization of this display prior to the recognizable beginning of Jack’s turn—what Hoey terms a “prebeginning sigh”—projects the dispreferred nature of his own incipient score report, as does the silence at line 10 (which further delays Jack’s response).

After the Chair explicitly calls for Jack’s score at line 15, Jack reports his score at line 16. The fact that Jack goes on to hedge this report by also announcing that he “can be talked down” further formulates the score divergence as problematic. The primary reviewer (Dharanipragada) acknowledges this announcement through a series of vertical head nods produced both in partial overlap with Jack’s talk and following its completion.

Thus far, though the reviewers have not yet displayed any orientation to the talk as inviting laughter, there has been evidence that the score difference between the primary and secondary reviewers is being treated as notable by the participants. The delayed production of Jack’s score report, and particularly his use of a sigh to project a potentially dispreferred next action, reflexively display Jack’s own understanding of his score report as being in some way problematic and disaffiliative. The readiness with which Dharanipragada nods in acknowledgement of Jack’s announcement of his willingness to change scores (lines 16–17) similarly shows that such a move is not unexpected even given the relatively slight divergence in reviewer scores.

It is not until line 21 that we see the first laugh-relevant display in the exchange, as the tertiary reviewer, Moreau, produces a tight-mouthed smile. Moreau continues to smile until the Chair prompts her score report at line 21. In response, Moreau reports having assigned the application a score of five, which positions her as being in divergence with both the primary and secondary reviewers (Dharanipragada and Jack). Like Jack before her, Moreau follows her score report with a hedge, stating that she was “on the fence” (lines 22–25). She thus downgrades her commitment to her written score and indicates her willingness to change scores. As Moreau articulates her hedge, she is audibly and visibly smiling, and she immediately follows her hedge with post-positioned laughter (Shaw, Hepburn, & Potter 2013) that reflexively displays her recognition of the divergence of her score and the delicacy of her report as calling for this laughter, while also inviting others to join in the laughter as well (Jefferson, 1979).

Two other panelists, Anwar and Sun, respond to Moreau’s announcement by returning her smile at lines 27–28, and they join her in laughing at lines 29–30. Though the primary reviewer (Dharanipragada) and the Chair both resist joining this laughter by simply acknowledging Moreau’s announcement at lines 29–30, Dharanipragada does soon join Anwar and Sun in their shared laughter at lines 34–36. In overlap with the Chair’s talk, the secondary reviewer (Jack), who has been gazing at Moreau since the silence preceding her announcement (line 25), smiles at Moreau while repeating the score of five she has just reported.

The shared laughter and multimodal laugh-relevant practices seen here reflexively confirm that panelists understand the reporting of score divergence as an interactionally delicate action that calls for some added interactional work toward resolution. Shared laughter and other laugh-relevant practices are resources for resolving this tension, and we see that interactants who are themselves the source of this tension (e.g., Moreau, in this instance) may do work to specifically invite this shared laughter from other members of the panel.

While shared laugh practices often accompany reports of significant score divergence, such reports can and do occasionally proceed without laughter. However, even in these apparently exceptional cases, we may see evidence that group members still orient to score divergence as potentially laughable. Such is the case in Excerpt 6 below, which takes place during a review of the “Williams” grant. Here the Chair is the primary reviewer for the grant, and, as a consequence, the Vice Chair takes on the role of chairperson throughout the discussion of this grant. There is a brief transition period in which the Chair hands off chairing duties to the Vice Chair, and as a result the score-reporting sequence is initiated using an atypical, abridged format, with the primary reviewer (the erstwhile Chair) volunteering his preliminary score at line 9.

(6) Some Interesting Discussion (Williams 2–6)

At line 9 the primary reviewer (the Chair) announces that he has assigned the grant a score of five. As the sequence unfolds, it becomes evident that his score is in stark contrast to the scores of three and two reported by the secondary reviewer (Zhou) and tertiary reviewer (Vitantonio) at lines 15 and 18. Following the reporting of these scores, the Vice Chair repeats the tertiary reviewer’s score and formulates the score range at line 19 (“You have two. Five three and two:.”). Shortly after the Vice Chair begins this turn, another participant, Thompson, produces a tight-lipped smile and shifts his gaze toward the Vice Chair (see Figure 4). Through this visible smile and shift in gaze toward the Vice Chair, Thompson displays a readiness to display an understanding of the score divergence as laughable, and he may also anticipate the Vice Chair’s formulation of the range in such a manner as to invite shared laughter from the group. However, the Vice Chair remains visibly and hearably serious as he completes his formulation of the score range at line 19, and upon completion of this action, he turns his gaze away from the tertiary reviewer to look at the primary reviewer (the Chair) at line 21. As the Vice Chair’s gaze shifts between these parties, it briefly alights on Thompson, who is seated between the primary and tertiary reviewers. Just as the Vice Chair’s gaze passes him, Thompson ceases smiling, thereby displaying a recognition of the Vice Chair’s serious stance and that the score divergence will not, in fact, be taken up as a laughable (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Thompson smiles while gazing at the Vice Chair

Figure 5.

Thompson ceases smiling as the Vice Chair’s gaze moves to the Chair

While the Vice Chair does produce an indirect assessment of the score range at line 25 (“It will be some interesting discussion”), his formulation of this assessment is devoid of any laugh-relevant practices, and it is not taken up by the other panelists as a laughable. Additionally, as the primary reviewer begins his review of the grant in partial overlap with the Vice Chair’s assessment (lines 25–26), thereby eliminating any further opportunities for the participants to invite or engage in laughter. Though a multitude of factors likely contribute to the lack of multiparty laughter in response to the reported score divergence in this excerpt, it provides a clear example of an embodied display of willingness on the part of at least one participant to publically orient to the divergent scores as occasioning laughter. In this way, this apparently deviant case still supports our observation that moments of significant score divergence are treated by the peer review meeting participants in our data as delicate moments where laughter may be relevant.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Through our identification and close analyses of the characteristics of the score-reporting sequence in peer review meeting interaction, our intention has been to demonstrate that and how laughter serves as a valuable resource as peer reviewers navigate moments of disagreement and disaffiliation. During the score-reporting sequence, assigned reviewers announce the preliminary scores they have previously assigned to a grant, in writing and online, at an earlier stage of the review process. As the activity through which the reviewers officially initiate the review of each grant, the score-reporting sequence significantly contributes toward establishing the tone and frame of the discussion to follow. As we have shown, this initial phase regularly unfolds as the locus of sensitive interactional navigation, as each reviewer provides a public report of what very rapidly emerges as a convergent or divergent evaluative stance relative to the score reports of other assigned reviewers. In our data, the initial score-reporting phases of the panel meetings are a routine site in which laugh practices are introduced as a reflexive means for navigating in and out of the delicacy that explicit divergence of opinion introduces to the institutional task and to interpersonal relations (cf. Glenn & Holt, 2013).10 The concept of reflexivity is appropriate here in that the delicacy of doing divergence is not only indexed by laugh practices, but it is also managed by them, as shared laughter provides an opportunity for participants to jointly engage in smoothing the potential awkwardness of the moment after divergent scores are first reported.

We have noted that what makes peer review panel meetings activities for which delicacy-mitigating laughter may be particularly useful is that such institutional activities are, by design, gatherings in which outstanding scholars in a field are specifically charged with reporting and supporting potentially conflicting perspectives on the merits of new scientific research. Given this institutional requirement, the normative avoidance of direct disagreement that operates in ordinary conversational interaction cannot, in principle, be avoided by peer reviewers. We might expect that this observation holds in other meeting environments where similar evaluative tasks are the norm, many of which have already been the subject of interactional analysis; as previously mentioned, these include guild admission meetings (McKinlay & McVittie, 2006), academic curriculum proposal meetings (Barnes, 2007), and teaching-team meetings for evaluating student achievement documents (Mazeland & Berenst, 2008). The phenomenon we describe here, in which participants engage in interactional work to mitigate displays of divergent positions that are all but required given the institutional task set before them, may thus be part of a more general pattern observable in other types of meeting talk as well.

As the assigned reviewers report their initial scores, they and other participants monitor how scores compare, and also how reviewers compare in their tendencies to give higher or lower scores, trends which emerge across applications (see Excerpt 3). Indeed we find that monitoring of the scoring patterns can motivate explicit “policing,” whereby individual meeting members call into question the legitimacy of a score, and by extension, the legitimacy of an assigned reviewer’s own expertise (Pier et al., 2017). The scoring process is thus of immediate consequence to the social and professional standings of the meeting participants as they construct their professional expertise in situ during the meeting. In making the simple request, “So preliminary scores?”, the meeting chair is in fact initiating a socially consequential sequence in which divergence and accountable disagreement, though endemic to the institutional activity, is still in clear need of interactional management. As our analyses show, laughter is a vital resource as participants navigate these moments of divergence and disagreement to achieve the institutional task at hand while also maintaining affiliative interpersonal relations.

Figures 2 and 3.

Jack sighs following Dharanipragada’s score report

Highlights.

This paper examines episodes of shared laughter in peer review interactions

Such laughter is found to routinely occur as participants display divergence of opinion

Participants use laughter as a resource to manage the divergence of evaluative positions that characterizes the give and take of joint grant evaluation

Laughter in these contexts additionally displays a reflexive understanding of this divergence in opinion as interpersonally delicate and in need of interactional management

Biographies

Joshua Raclaw is Assistant Professor in the Department of English at West Chester University and Visiting Scientist at the Center for Women’s Health Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research draws on conversation analysis and other discourse analytic methods to examine language and social practice in meetings and everyday conversations, embodiment and the use of mobile media in interaction, turn-initial particles and discourse markers in American English, and issues of language, communication, and identity in the United States, particularly with respect to gender and sexuality.

Cecilia E. Ford is Professor of Sociology and Nancy Hoefs Professor of English, University of Wisconsin–Madison, and she is an affiliate at Center for Women’s Health Research. Ford draws on conversation analysis to document how humans construct—on a moment-by-moment basis—the order of their social lives, including the emergent practices we call language. She is particularly fascinated by interaction within and between turns at talk and the mutually contextualizing flow of lexico-syntax, sound production, and physical movement. Her current focus is on peer review interaction, joint affect displays, and compassionate communication (“Non-Violent Communication”).

Footnotes

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM111002, Exploring the Science of Scientific Review. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

See Pier et al. (2015) for a full description of the design and implementation of the peer review panels examined in this study.

Reviewers are provided with these details of the scoring rubric prior to the grant review period, though there is evidence that reviewers’ individual understanding of these scores are fluid and subjective, and during meetings reviewers actively work toward negotiating shared understandings of the “meaning” of a score (Pier et al., 2015).

A copy of the review template used by reviewers can be downloaded from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/peer/critiques/rpg_critique_template.doc

These identifications refer to the order in which those reviewers deliver their overview of the application’s strengths and weaknesses during the panel meeting itself.

One reviewer drew our attention to possible similarities between the uses of laughter in our data and what Jefferson (1984) has identified as troubles-resistant laughter. Looking at similarities and differences in the use of laugh-practices in these two different but delicate activities would certainly prove fruitful. One immediately identifiable difference between laughter in score-reporting and laughter in troubles telling sequences is that score reports are not, in themselves, troubles tellings. However, through the action of reporting a divergent score, a reviewer may be introducing interactional “trouble” into the unfolding sequence. Laugh-practices initiated by such reviewers can thus serve both to reflexively mark the action as problematic while also distancing the actor from the potential seriousness of the action. In a very different but still delicate sequence type, bad news delivery, Maynard notes the potential for a mismatch between the seriousness of the news and the laugh-practice (smiling) with which an instance of bad news is delivered, the smile being “at odds with the message” (2003:51). In the case he reports, however, rather than merely distancing the teller from the seriousness of the action, the smile also confuses the news recipient, who at first fails to understand the message as indeed serious.

The chair’s confirmation of the secondary reviewer’s score at line 12 is articulated with both smile voice and a notable “wobble” (Ford & Fox, 2011), qualities that are laugh-relevant. Though the laughter surrounding score reports is most commonly seen in cases of score divergence, it features in episodes of score convergence as well. In these contexts, laughter displays recognition of the reviewers’ shared stance toward a grant. In contrast to episodes of laughter that mark score divergence, laughter directed toward score convergence is shared between individual participants rather than fully shared by the group.

An accurate Praat picture of the pitch trace of the Chair’s talk was not possible, given the significant creaky voice he used in producing the word “five.”

The mis-start involves RD initiating the fuller report of his evaluation prior to all three assigned reviewers announcing their preliminary scores. Note that RD apologizes (line 8) for his misplaced action and subsequently restarts the report at line 42, the proper position in the normative structure of these meetings.

Given what we know about laughter and the management of delicate interactional moments, it is not surprising that, in examining other phases of the peer review panel meetings, we find that it is not only in the score-reporting sequence but also elsewhere in review meeting talk that laughter emerges as a resource for managing disaffiliation (Authors, 2016).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahlqvist Veronica, Andersson Johanna, Berg Hahn, Cecilia Kolm, Camilla Söderqvist, Lisbeth, Tumpane John. Observations on gender equality in a selection of the Swedish Research Council’s evaluation panels. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arminen Ilkka, Halonen Mia. Laughing with and at patients: The roles of laughter in confrontations in addiction therapy. The Qualitative Report. 2007;12(3):483–512. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JA, Lehmann-Willenbrock N, Rogelberg SG, editors. The science of meetings at work: The Cambridge handbook of meeting science. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2015. Meetings as interactional achievements: A conversation analytic approach; pp. 247–276. Authors. [Google Scholar]

- “Score calibration talk” and its impact: A conversation analytic investigation of reviewer interaction during NIH Study Section meetings. Paper presented at the 8th Conference on Understanding Interventions that Broaden Participation in Science Careers; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 2016. Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes Rebecca. Formulations and the facilitation of common agreement in meetings talk. Text & Talk. 2007;27(3):273–296. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma Paul, Weenink David. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer program]. Version 6.0.16. 2013 retrieved April 1, 2015 from http://www.praat.org/

- Clift RebeccaJ. Visible deflation: Embodiment and emotion in interaction. Research on Language & Social Interaction. 2014;47(4):380–403. [Google Scholar]

- Couper-Kuhlen Elizabeth. A sequential approach to affect: The case of ‘disappointment’. In: Haakana M, Laakso M, Lindström J, editors. Talk in interaction: Comparative dimensions. Finnish Literature Society; 2009. pp. 94–123. [Google Scholar]

- Drew Paul. Po-faced receipts of teases. Linguistics. 1987;25:219–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fatigante Marilena, Orletti Franca. Laughter and smiling in a three-party medical encounter: Negotiating participants’ alignment in delicate moments. In: Glenn P, Holt E, editors. Studies of laughter in interaction. London: Bloomsbury Academic; 2013. pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ford Cecilia E, Fox Barbara A. Multiple practices for constructing laughables. In: Barth-Weingarten D, Reber E, Selting M, editors. Prosody in interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2011. pp. 339–368. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo Stephen A, Carpenter Afton S, Glisson Scott R. Teleconferenec versus face-to-face scientific peer review of grant application: Effects on review outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn Phillip. Laughter in interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn Phillip, Holt Elizabeth. Introduction. In: Glenn P, Holt E, editors. Studies of laughter in interaction. London: Bloomsbury Academic; 2013. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn Phillip. Interviewees volunteered laughter in employment interviews: A case of “nervous” laughter? In: Glenn P, Holt E, editors. Studies of laughter in interaction. London: Bloomsbury Academic; 2013. pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Haakana Makoto. Laughter as a patient’s resource: Dealing with delicate aspects of medical interaction. Text. 2001;21:187–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn Alexia, Bolden Galina. The conversation analytic approach to transcription. In: Sidnell J, Stivers T, editors. The handbook of conversation analysis. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hoey Elliott. Sighing in interaction: Somatic, semiotic, and social. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2014;47(2):175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Holt Liz. Using laugh responses to defuse complaints. Research on Language & Social Interaction. 2012;45(4):430–448. [Google Scholar]

- Jacknick Christine M. “‘Cause the textbook says...”: Laughter and student challenges in the ESL classroom. In: Glenn P, Holt E, editors. Studies of laughter in interaction. London: Bloomsbury Academic; 2013. pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson Gail. A technique for inviting laughter and its subsequent acceptance/declination. In: Psathas G, editor. Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology. New York: Irvington; 1979. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson Gail. On the organization of laughter in talk about troubles. In: Atkinson JM, Heritage J, editors. Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 346–369. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson Gail, Sacks Harvey, Schegloff Emanuel A. Notes on laughter in the pursuit of intimacy. In: Button G, Lee JRE, editors. Talk and social organization. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters; 1987. pp. 152–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont Michèle. How professors think: Inside the curious world of academic judgment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner Gene H. On the place of hesitating in delicate formulations: A turn-constructional infrastructure for collaborative indiscretion. In: Sidnell J, Hayashi M, Raymond G, editors. Conversational repair and human understanding. Cambridge University Press; 2013. pp. 95–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner Gene. On the syntax of sentences-in-progress. Language in Society. 1991;20:441–458. [Google Scholar]

- Kangasharju Helena, Nikko Tuija. Emotions in organizations: Joint laughter in workplace meetings. Journal of Business Communication. 2009;46(1):100–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mazeland Harrie, Berenst Jan. Sorting pupils in a report-card meeting: Categorization in a situated activity system. Text & Talk. 2008;28(1):55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Douglas. Bad News, Good News: Conversational Order in Everyday Talk and Clinical Settings. University of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay Andy, McVittie Chris. Using topic control to avoid the gainsaying of troublesome evaluations. Discourse Studies. 2006;8(6):797–815. [Google Scholar]

- Osvaldsson Karin. On laughter and disagreement in multiparty assessment talk. TEXT. 2004;24:517–545. [Google Scholar]

- Pier Elizabeth L, Raclaw Joshua, Nathan Mitchell, Kaatz Anna, Carnes Molly, Ford Cecilia E. Studying the study section: How collaborative decision making and videoconferencing impacts the grant peer review process. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 2015. Wisconsin Center for Education Research Working Paper Series. [Google Scholar]

- Pier Elizabeth L, Raclaw Joshua, Kaatz Anna, Carnes Molly, Nathan Mitchell J, Ford Cecilia E. “Your comments are meaner than your score”: How Score Calibration Talk influences inter-panel variability during scientific grant peer review. Research Evaluation. 2017;26(1):1–14. doi: 10.1093/reseval/rvw025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz Anita. Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In: Atkinson JM, Heritage J, editors. Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 57–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz Anita, Heritage John. Preference. In: Sidnell J, Stivers T, editors. The handbook of conversation analysis. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2012. pp. 210–228. [Google Scholar]

- Potter Jonathan, Hepburn Alexa. Putting aspiration into words: “Laugh particles,” managing descriptive trouble and modulating action. Journal of Pragmatics. 2010;42(6):1543–1555. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks Harvey. On the preferences for agreement and contiguity in sequences in conversation. In: Button G, Lee JRE, editors. Talk and social organization. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters; 1987. pp. 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sert Olcay, Jacknick Christine M. Student smiles and the negotiation of epistemics in L2 classrooms. Journal of Pragmatics. 2015;77:97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw Chloe, Hepburn Alexa, Potter Jonathan. Having the last laugh: On post completion laughter particles. In: Glenn P, Holt E, editors. Studies of laughter in interaction. London: Bloomsbury Academic; 2013. pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]