Abstract

Background: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease that is a source of significantly decreased life expectancy in the United States. This study investigated causes of deaths among males and females with SLE.

Materials and Methods: This cross-sectional study used the national death certificate database of ∼2.7 million death records in the United States, 2014. SLE was defined using Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases codes: M32.1, M32.9, and M32.8. We compared sex-stratified demographic characteristics and the most commonly listed comorbidities in decedents with and without SLE. Relative risks (RRs) quantified the risk of dying with the most commonly listed comorbidities among decedents with SLE aged ≤50 years compared with non-SLE decedents.

Results: There were 2,036 decedents with SLE in the United States (86.2% female). Female SLE decedents were 22 years younger than non-SLE females (median: 59 years vs. 81 years). This difference was 12 years among male decedents (median: 61 years vs. 73 years). The most frequently listed causes of death among female SLE decedents were septicemia (4.32%) and hypertension (3.04%). In contrast, heart disease (3.70%) and diabetes mellitus with complications (3.61%) were the most common among male SLE decedents. Among younger male decedents, SLE had higher co-occurrence of coagulation/hemorrhagic disorders and chronic renal failure compared with non-SLE (RR = 16.69 [95% confidence interval {CI} = 10.50–27.44] and RR = 5.76 [95% CI = 2.76–12.00], respectively). These also contributed to premature mortality among women (RR = 4.98 [95% CI = 3.69–6.70] and 8.55 [95% CI = 6.89–10.61], respectively).

Conclusions: Our findings identify clinically relevant comorbidities that may warrant careful consideration in patients' clinical management and the natural history of SLE.

Keywords: : lupus, mortality, gender disparities, comorbidities

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease with variable clinical and immunological presentation and is a source of significantly decreased life expectancy in the United States. The multisystemic presentations of the disease, including dermatological, musculoskeletal, and particularly internal organ involvement, are key contributors to disease morbidity.1 One of the major imponderables characterizing SLE is the marked differences between the sexes in terms of the incidence, prevalence, and clinical manifestations. In a recent study, the prevalence of SLE per 100,000 Medicaid-enrolled adults was 192 in females and 32 in males.2 Women of childbearing age are disproportionately impacted; the female to male incidence ratio in this age group is 9:1.3 Potential biological underpinnings of these differences have been attributed to the pathogenic effects of estrogen and its hydroxylation, protective effects of androgens and testosterone, and X-chromosome-linked disease susceptibility.1,4,5 However, this area is still poorly understood.

The epidemiology of SLE also has a complex gendered aspect. For example, the prevalence estimates on SLE may be an artifact of gender bias because of selective attention to females by physicians during clinical decision-making, thus, contributing to the underdiagnosis among males. There are conflicting reports concerning the severity of SLE disease between males and females. For instance, female SLE patients have more frequent disease exacerbations in general, but male patients appear to have significantly greater multisystemic damage accrual and disease severity than females.1,6,7 However, underdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis in males may partly contribute to greater disease severity and damage accrual compared with female lupus patients.8 In addition, male patients often present with different clinical manifestations than female patients. Most studies have identified infections, cardiovascular, and renal manifestations as being more common in males, while mucocutaneous and musculoskeletal manifestations appear to be more frequent in female SLE patients.9–11

Much is unknown about population-based trends related to mortality, including proximate and more distal causes of deaths associated with SLE, particularly through a sex-based lens. Although mortality rates among SLE patients have improved drastically in recent years, one systematic review revealed a higher mortality rate in male compared with female SLE patients in most studies that have addressed this question.12 While several studies have investigated cause of death among SLE patients within established cohorts,13–18 much of our understanding of the multiple causes of death in population-based contexts have been from studies outside of the United States.19,20 These countries have dissimilar sociodemographic population composition and determinants of health compared with the United States, thus, limiting the generalizability of their study findings to the American context. There is also a relative dearth in the literature concerning the causes of premature mortality in lupus (i.e., deaths not related to the natural aging process among SLE patients). However, active disease and infection have been shown to be important causes of death within the first 5 years after diagnosis.21

A comprehensive understanding of causes of death and the related comorbidities can improve clinical diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, impact survival outcomes in patients living with SLE, and enhance population-based disease surveillance estimates. Knowledge of the common combinations of comorbidities on SLE-related death certificates can also suggest the direction of future epidemiological research. The purpose of this study is to provide sex-stratified insight into SLE mortality by (1) describing the burden of mortality associated with and without SLE by examining the sociodemographic characteristics of these decedents, (2) comparing the most frequently cited comorbidities among decedents with and without SLE, and (3) calculating the relative risk (RR) of dying with the most commonly listed comorbid conditions among persons aged ≤50 years to provide a more nuanced understanding of premature mortality in this population.

Materials and Methods

Study population

We conducted an examination of SLE-related deaths using the 2014 National Center for Health Statistics multiple cause of death (MCOD) database, a population-based electronic medical recording of all death certificates issued in the United States and its territories. The MCOD data are compiled and disseminated by the National Center for Health Statistics.22 The MCOD file lists up to 20 medical conditions that are “diseases related to the morbid process leading to death” using the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). The underlying cause of death (UCOD), which is the condition listed last on the death certificate, is considered the condition that gave rise to all the other conditions preceding it. All additional conditions listed on the death certificate are termed as nonunderlying cause of death (NUCD) and may be immediate, intermediate, or contributory causes.22 Thus, the analyses will consider not only the number of death certificates listing SLE as the UCOD but also those listing SLE in general. We defined SLE-related deaths as records citing the following ICD-10 codes as UCOD or NUCD: M32.1 (SLE with organ or system involvement), M32.8 (other forms of SLE), and M32.9 (SLE, unspecified). The term non-SLE-related deaths or general population is used for decedents who did not have SLE listed as any cause of death.

Definition of study variables

We obtained demographic information on age, race/ethnicity, sex, educational attainment, foreign-born status, marital status, and pregnancy status. Age was categorized into the following groups: <15 years, 15–44 years, 45–64 years, and ≥65 years. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic (NH) white, NH black, American Indian, Asian Pacific Islander, and Hispanic. We also categorized country of origin as native born (in the United States) and foreign born. Decedents' highest educational attainment was defined as less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate and above. Marital status was classified as single, married, widowed, and divorced. We also classified evidence of pregnancy status from the death records for females, and this was categorized as not pregnant within the past year, pregnant at time of death, pregnant within 1 year before death, and not applicable. The risk of death was calculated using the 2014 U.S. census population estimates as the denominator and was age standardized using the 2000 U.S. standard population.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were stratified by sex. Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare the number of deaths by age and cause of death (UCD or NUCD) as appropriate. To determine the most frequently reported causes of death, ICD-10 codes among deaths with and without SLE were classified according to the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10.23 The CCS system categorizes more than 32,000 ICD-10 codes into a reduced 260 “clinical meaningful categories.”23 The median age at death for each of the top 10 CCS categories was calculated. RRs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the risk of dying with the top 10 most frequently listed comorbidities among decedents aged ≤50 years who had SLE using log-binomial models. The comparison group was non-SLE decedents belonging to the same age group. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

In 2014, there were 2,660,497 deaths in the United States, of which 2,036 (0.1%) listed SLE among the causes of death. This corresponded to an age-adjusted mortality of 0.58 per 100,000 people. SLE was the underlying cause of 1,180 deaths and any cause in an additional 856 deaths. Approximately 86.2% (n = 1,755) of SLE deaths were among females—corresponding to an age-adjusted mortality rate of 1.00 death per 100,000 females (Tables 1 and 2). SLE was the underlying cause of 1,104 deaths and listed as any cause of 741 deaths among female deaths. Among female decedents with SLE, the median age at death was 59 years with the highest proportion between 45 and 64 years of age at death (40.2%; Table 1). The overall median age at death for females in the general population was 81 years and the majority of deaths occurred among female decedents over 65 years (79.3%). Black females experienced the greatest burden of mortality compared with females of other race/ethnic groups; ∼32% of all female SLE decedents were black, although black females comprised only 11% of non-SLE-related deaths in the general population (Table 1). The age-adjusted risk of death among NH black females with SLE was 2.59 per 100,000 compared with a rate of 0.60 per 100,000 among NH white females (Table 2). Female decedents with SLE had a slightly higher proportion of foreign-born individuals compared with females in the general population (11.6% vs. 9.8%). There were no significant differences in educational attainment, marital status, and pregnancy status between female decedents with SLE and those in the general population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Decedents With and Without Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in the United States, 2014

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE | Non-SLE | SLE | Non-SLE | |

| Characteristics | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| <15 | 4 (0.2) | 14,315 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 18,480 (1.4) |

| 15–44 | 384 (21.9) | 49,777 (3.8) | 61 (21.7) | 99,609 (7.4) |

| 45–64 | 705 (40.2) | 207,925 (15.8) | 108 (38.4) | 323,288 (24.0) |

| ≥65 | 662 (37.7) | 1,040,299 (79.3) | 112 (39.9) | 906,804 (67.3) |

| Median age (years) | 59 | 81 | 61 | 73 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, NH | 839 (47.8) | 1,031,382 (78.6) | 165 (58.7) | 1,036,560 (79.0) |

| Black, NH | 560 (31.9) | 148,618 (11.3) | 66 (23.5) | 155,002 (11.5) |

| American Indian | 19 (1.1) | 7,784 (0.6) | 4 (1.4) | 9,343 (0.7) |

| Asian/PI | 68 (3.9) | 29,918 (2.3) | 7 (2.5) | 32,062 (2.4) |

| Hispanic | 214 (12.2) | 77,130 (5.9) | 36 (12.8) | 93,255 (6.9) |

| Unknown | 55 (3.1) | 17,484 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) | 21,959 (1.6) |

| Foreign status | ||||

| Native born | 1,551 (88.4) | 1,183,465 (90.2) | 247 (87.9) | 1,215,683 (90.2) |

| Foreign born | 204 (11.6) | 128,851 (9.8) | 34 (12.1) | 132,498 (9.8) |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Less than high school | 271 (15.4) | 303,645 (23.1) | 45 (16.0) | 306,881 (22.8) |

| High school graduate | 710 (40.5) | 584,668 (44.6) | 113 (40.2) | 530,004 (39.3) |

| Some college | 466 (26.6) | 232,574 (17.7) | 68 (24.2) | 237,997 (17.7) |

| College graduate and above | 280 (16.0) | 168,416 (12.8) | 50 (17.8) | 242,222 (18.0) |

| Unknown | 28 (1.6) | 23,013 (1.8) | 5 (1.8) | 31,077 (2.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 408 (23.3) | 128,627 (9.8) | 75 (27.0) | 210,324 (15.6) |

| Married | 672 (38.3) | 327,068 (24.9) | 152 (54.1) | 663,133 (49.2) |

| Widowed | 319 (18.2) | 661,729 (50.4) | 19 (6.8) | 246,057 (18.3) |

| Divorced | 341 (19.4) | 189,453 (14.4) | 34 (12.1) | 215,484 (16.0) |

| Unknown | 15 (0.9) | 5,439 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 13,183 (1.0) |

| Pregnancy status | ||||

| Not pregnant within the past year | 437 (24.9) | 67,560 (5.2) | N/A | N/A |

| Pregnant at time of death | 0 (0.0) | 639 (0.1) | ||

| Pregnant within 1 year before death | 1 (0.1) | 995 (0.1) | ||

| Not applicable | 1,053 (60.0) | 1,160,046 (88.4) | ||

| Unknown | 264 (15.0) | 83,076 (6.3) | ||

| Total | 1,755 (100.0) | 1,312,316 (100.0) | 281 (100.0) | 1,348,181 (100.0) |

N/A, not applicable; NH, non-Hispanic; PI, Pacific Islander; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Table 2.

Age-Adjusted and Age-Specific Mortality Rates of Decedents With and Without Systemic Lupus Erythematosus by Demographic Characteristics in the United States, 2014

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | SLE | Non-SLE | SLE | Non-SLE |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| <15 | 0.01 | 47.90 | 0.00 | 59.26 |

| 15–44 | 0.61 | 78.57 | 0.09 | 154.07 |

| 45–64 | 1.65 | 485.93 | 0.27 | 793.40 |

| ≥65 | 2.56 | 4017.85 | 0.55 | 4455.76 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, NH | 0.60 | 629.83 | 0.13 | 872.57 |

| Black, NH | 2.59 | 729.97 | 0.40 | 1068.67 |

| American Indian | 1.40 | 680.63 | 0.51 | 942.28 |

| Asian/PI | 0.68 | 339.54 | 0.08 | 480.68 |

| Hispanic | 0.98 | 438.96 | 0.16 | 637.04 |

| Unknown | — | — | — | |

| Total | 0.95 | 620.85 | 0.17 | 868.98 |

The risk of death, characterized by mortality rates, was calculated using the 2014 U.S. census population estimates as the denominator and were age standardized using the 2000 U.S. standard population.

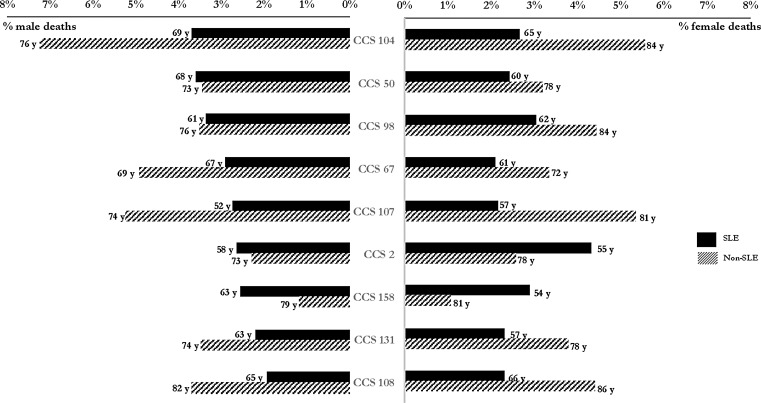

The most frequently listed comorbidities among female decedents with SLE were septicemia and hypertension (4.32% and 3.04%, respectively; Fig. 1). Decedents with SLE were an average 11–27 years younger than those without SLE for their 10 most frequent causes of death (Fig. 1). The largest age difference among women was observed for chronic renal failure (57 years vs. 81 years). For deaths among females in the general population, neither septicemia nor chronic renal failure was in the top 10. Senility and organic mental disorders (6.86% of female decedents in the general population) and acute cerebrovascular disease (2.70% of female decedents in the general population) were listed as top causes in the female general population but not among female decedents with SLE. These deaths ranked 30th (0.98% of SLE decedents) and 19th (1.26% of SLE decedents) among females with SLE, respectively. Among female decedents aged ≤50 years, chronic renal failure and coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders (RRs = 8.55 [95% CI = 6.89–10.61] and 4.98 [95% CI = 3.69–6.70], respectively) were comorbidities significantly associated with premature deaths in SLE decedents (Table 3). Young female decedents with SLE were significantly less likely to die with cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation and respiratory failure as causes of death (RRs = 0.64 [95% CI = 0.49–0.84] and 0.86 [95% CI = 0.66–1.13], respectively; Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Top causes of death listed in decedents with and without SLE in the United States (presented as % of all 2014 deaths by sex and median age at death in years), 2014. CCS 104: Other and ill-defined heart disease; CCS 50: Diabetes mellitus with complications; CCS 98: Essential hypertension; CCS 67: Substance-related mental disorders; CCS 107: Cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation; CCS 2: Septicemia (except in labor); CCS 158: Chronic renal failure; CCS 131: Respiratory failure; CCS 108: Congestive heart failure (nonhypertensive). CCS, Clinical Classifications Software; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Table 3.

Most Frequently Listed Categories of Causes of Death Among Female Decedents Aged ≤50 Years With and Without Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in the United States, 2014

| With or without SLE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCS category | With/without CCS category | With SLE (n = 2,017), n (%) | Without SLE (n = 275,292), n (%) | RR (95% CI) |

| CCS 2: Septicemia (except in labor) | With | 113 (5.6) | 1,904 (0.7) | 2.41 (2.01–2.89) |

| CCS 158: Chronic renal failure | With | 84 (4.2) | 1,341 (0.5) | 8.55 (6.89–10.61) |

| CCS 157: Acute and unspecified renal failure | With | 53 (2.6) | 2,469 (0.9) | 2.93 (2.24–3.83) |

| CCS 131: Respiratory failure; insufficiency; arrest (adult) | With | 52 (2.6) | 8,255 (3.0) | 0.86 (0.66–1.13) |

| CCS 259: Residual codes; unclassified | With | 51 (2.5) | 6,350 (2.3) | 1.10 (0.84–1.44) |

| CCS 107: Cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation | With | 50 (2.5) | 10,643 (3.9) | 0.64 (0.49–0.84) |

| CCS 98: Essential hypertension | With | 49 (2.4) | 3,550 (1.3) | 1.88 (1.42–2.49) |

| CCS 62: Coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders | With | 44 (2.2) | 1,207 (0.4) | 4.98 (3.69–6.70) |

| CCS 122: Pneumonia (except that caused by tuberculosis or sexually transmitted disease) | With | 40 (2.0) | 4,206 (1.5) | 1.30 (0.95–1.77) |

| CCS 97: Peri-; endo-; and myocarditis; cardiomyopathy (except that caused by tuberculosis or sexually transmitted disease) | With | 39 (1.9) | 1,978 (0.7) | 2.51 (1.83–3.44) |

CCS, Clinical Classifications Software; CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Male deaths with SLE represented 13.8% (n = 281) of all SLE-related deaths in the United States in 2014 (Table 1). The age-standardized risk from SLE was 0.17 deaths per 100,000 people. SLE was the underlying cause of 166 deaths and as any cause of 115 deaths among male deaths. Among male decedents with SLE, the median age at death was 61 years (Table 1). The overall median age at death for males in the general population was 73 years and the highest proportion of deaths occurred among male decedents over 65 years (67.3%). Although black males comprised ∼12% of deaths in the general population, this group comprised 23.5% of male decedents with SLE (Table 1). The age-standardized mortality was highest among American Indian males (0.51 per 100,000 people), compared to 0.13 per 100,000 NH white males (Table 2). There were no other demographic differences related to SLE among male decedents (Table 1).

The most frequently listed condition among male SLE decedents was heart disease and diabetes mellitus with complications (3.70% and 3.61%, respectively; Fig. 1). Among the 10 most frequently cited causes among males, deaths listing SLE occurred an average median age of 5–22 years younger than deaths not listing SLE (Fig. 1); the lower end of this range was represented by diabetes mellitus with complications and the upper end of this range was represented by cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation (2.73% of male decedents with SLE). Septicemia, coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders, and chronic renal failure were not listed in the top 10 categories of deaths among males in the general population. However, among male decedents in the general population external causes of injury and poisoning (4.40%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3.66%), and senility and organic mental disorders (3.33%) were listed as top causes, while these conditions were not listed among the top 10 categories among male decedents with SLE. These deaths ranked 12th (1.94% of SLE decedents), 13th (1.85% of SLE decedents), and 28th (1.06% of SLE decedents) among males with SLE, respectively. Among male decedents aged ≤50 years, the RRs for comorbidities associated with a significantly increased risk of premature SLE-related death ranged from 16.69 (95% CI = 10.50–27.44; coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders) to 5.76 (95% CI = 2.76–12.00; chronic renal failure; Table 4). External causes of injury/poisoning and substance-related mental disorders (RRs = 0.14 [95% CI = 0.07–0.28] and RRs = 0.51 [95% CI = 0.25–1.06], respectively) were the two conditions associated with a significantly decreased risk of premature death among male decedents with SLE.

Table 4.

Most Frequently Listed Categories of Causes of Death Among Male Decedents Aged ≤50 Years With and Without Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in the United States, 2014

| With or without SLE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CCS category | With SLE (n = 326), n (%) | Without SLE (n = 490,774), n (%) | RR (95% CI) |

| CCS 62: Coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders | 15 (4.6) | 1,353 (0.3) | 16.69 (10.5–27.44) |

| CCS 107: Cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation | 15 (4.6) | 15,409 (3.1) | 1.47 (0.89–2.40) |

| CCS 98: Essential hypertension | 11 (3.4) | 6,635 (1.4) | 2.49 (1.40–4.46) |

| CCS 2: Septicemia (except in labor) | 9 (2.8) | 7,317 (1.5) | 1.85 (0.97–3.53) |

| CCS 50: Diabetes mellitus with complications | 9 (2.8) | 8,528 (1.7) | 1.59 (0.83–3.03) |

| CCS 260: E Codes: All (external causes of injury and poisoning) | 8 (2.5) | 84,692 (17.3) | 0.14 (0.07–0.28) |

| CCS 67: Substance-related mental disorders | 7 (2.1) | 20,670 (4.2) | 0.51 (0.25–1.06) |

| CCS 131: Respiratory failure; insufficiency; arrest (adult) | 7 (2.1) | 9,531 (1.9) | 1.11 (0.53–2.30) |

| CCS 134: Other upper respiratory disease | 7 (2.1) | 2,197 (0.4) | 4.80 (2.30–9.99) |

| CCS 158: Chronic renal failure | 7 (2.1) | 1,829 (0.4) | 5.76 (2.76–12.00) |

Discussion

Using MCOD data, this study identified sex-based differences in the causes of death among SLE decedents in the United States and offers an opportunity to better describe the association between SLE and other associated comorbidities in the context of mortality. One key finding of the current study is that SLE conferred an average 22-year and 12-year deficit in life expectancy among females and males, respectively, compared to the general population. However, we found no appreciable difference in the age distribution and median age at death between male and female decedents with SLE (∼60 years), which was consistent with a previously published MCOD study among SLE patients in France.19 A previously published Brazilian study found age at death of SLE patients to be much younger than our population, with no difference between males and females.20 Our population is more similar to the French population than the Brazilian population in terms of socioeconomic factors and structural determinants of health, and this may explain the similarities in mortality metrics with the French population. The French study also found that death before 40 years was more common among females when compared with males.19 Previous studies have shown that although the prevalence of SLE is much lower in males than females, male SLE may be more severe and have less favorable long-term outcomes than SLE in females.12 We found an age-adjusted mortality risk ratio between females and males to be 5.6:1, while the study conducted in Brazil found this ratio to be 9:1.20 When we examined age-specific mortality ratios between females and males, we found an attenuation of this ratio with increasing age. The ratio was 6.77, 6.11, and 4.55 among those aged 15–44 years, 45–64 years, and ≥65 years, respectively. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that SLE prevalence ratios decrease after menopause.5,12,24,25

The same leading comorbid conditions observed in the context of SLE mortality also afflict the general population, that is, heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes. This finding was consistent with the France mortality study.19 The preponderance of these conditions among SLE patients reflect trends found in prevalence-incidence research studies. SLE has long been established as an independent risk factor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) through a pathway likely mediated by several inflammatory mechanisms.26 In recognition of these trends, interventions for achieving substantial decreases in CVD-related deaths among patients with SLE are similar to those required in the general population. Our findings suggest that this may include helping patients change behaviors, such as smoking, as well as promoting aspirin use, healthful diet and physical activity to combat obesity, and screening patients for diabetes, hypertension, and lipid disorders. Although these preventive services aim to reduce the prevalence of traditional risk factors for CVD, empirical studies are needed to elucidate the extent of residual risk conferred by SLE-related means (e.g., long-term use of drug therapies, clinical, and immunological factors) after accounting for traditional risk factors. Furthermore, this needs to be framed in a manner that accounts for the earlier onset of CVD that manifests in a younger age at death among SLE patients.

Infectious diseases are important sources of morbidity and mortality for patients with SLE. In our analyses, septicemia was the leading cause of death among female decedents with SLE. The biological underpinnings of the increased burden of infectious diseases seen in patients with SLE may be attributed to the natural course of the autoimmune disease itself, the therapeutics used for treatment, or the complex interactions between these factors.9 Also, in line with previous research, renal manifestations were top comorbidities among SLE decedents in this study, with equal prevalence in males and females. However, we found that median age at death for female SLE decedents with chronic renal failure was 54 years, while the median age at death for male SLE decedents with this comorbidity was 63 years. This finding may appear inconsistent with previous research, indicating that male patients with lupus nephritis, a severe manifestation of SLE, have more significant renal dysfunction and laboratory abnormalities than female patients.2,12 We cannot rule out the possibility that this paradoxical finding in the age at death may be due to later age at diagnosis, surveillance bias, disparate case fatality rate, and more aggressive treatment related to kidney disease among males. It should be noted that the difference in the age at death between lupus and nonlupus patients for a given condition may not necessarily be due to more severe disease or a worse inherent prognosis. For example, although lupus patients with chronic renal failure do die at a younger age, the cause of renal failure in SLE is most often lupus nephritis, which starts at a much younger age than the renal failure from diabetes/hypertension that affects the nonlupus group.27,28

Similarly, we found some variations in the burden of comorbidities associated with premature death among SLE decedents. There was a preponderance of hematological manifestations among SLE decedents aged ≤50 years, particularly among males compared to the general population. The median age at death for male SLE decedents with coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders was 46 years. Several studies suggest that males are more likely to exhibit hematological manifestations such as hemolytic anemia, lymphopenia, and thrombocytopenia.12 These clinical manifestations may also be induced by SLE-related drug therapies, for example, antimalarial and immunosuppressive drugs.29 Current research indicates that hematological manifestations are often some of the first signs of SLE and may precede diagnosis by several years.30 Future studies are needed to explicate this pathway and its impact on diagnosis trends and survival differentials between males and females.

It is well known that racial minorities have a disproportionately higher burden of mortality. While racial inequalities in healthcare outcomes in medicine are pervasive, the scope and degree of these differences in SLE are particularly pronounced.28,31 There are marked differences in how SLE afflicts individuals of different racial identities, including disparities in disease risk, clinical presentation, disease severity, and treatment response.2,28 Mortality studies since as early as the 1970s have shown that SLE mortality rates among black females are nearly four times as high as those in white females. We showed this trend toward sex differences within race/ethnic groups, unfortunately, has not improved using national data from 2014. American Indians had the lowest mortality ratio between females and males (2.71:1), while Asian Pacific Islanders experienced the highest ratio (8.50:1). These differences also reflect trends that exist among prevalent SLE cases.2 Not surprisingly, these findings reiterate that racial/ethnic minorities usually have the greatest and most complex SLE-related healthcare needs likely due to variations in socioeconomic disadvantages, pervasive marginalization, geographical factors, genetic predisposition, and psychosocial influences; these issues continue to shape the numerous health inequities that affect these populations. However, novel translational research programs are currently underway to address these disparities to avoid (re)polarizing SLE within society's most vulnerable populations (i.e., women and ethnic minorities).28

A number of limitations that are inherent to MCOD should be considered in the interpretation of the current study. First, the inaccuracy of MCOD on death certificates is an issue that can lead to the underestimation of SLE mortality burden; therefore, the SLE mortality estimates in this study may reflect only a fraction of the real burden.22 Also, misclassification of the UCOD due to the omission of SLE from the death certificate is a possible limitation. One study based on two SLE cohorts found that about 40% of patients with SLE did not have the disease recorded on their death certificate.32 Older patients and those without health insurance were less likely to have SLE recorded on their death certificates. We hypothesize that this may have misclassified the risk of death in minority populations (as this population is more likely to be underinsured) and older patients. Second, due to the nature of MCOD data, we cannot differentiate between causes of death that are related to the natural age process, disease activity, and drug therapy. We also cannot make definitive statements about differential survival because we do not have information about the diagnosis dates of the decedents. Finally, certain phenotypes of SLE (e.g., milder to moderate presentations with no lupus nephritis or other major organ involvement) are more likely to be missed during clinical management. Thus, these phenotypes may be underrepresented in the MCOD data. If these phenotypes vary by gender, then this selection bias could explain some of our findings. Despite these limitations, the MCOD data are vital because they are a complete source of all registered deaths in the United States, providing comprehensive understanding of population-based burden of SLE mortality.

In summary, we believe that our analysis is the most comprehensive population-based description of mortality differentials among SLE decedents in the United States. Our findings reinforce the urgent need for interventions that reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with SLE to improve health outcomes and ultimately reduce health disparities. These results identified clinically relevant comorbidities that need to be considered more carefully in the course of patients' clinical management and the natural history of SLE disease, elucidating future targets for the investigation of sex-based differences.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Chaichian is partially supported by the Dr. Elaine Lambert Lupus Fellowship via the John & Marcia Goldman Foundation. He also works on a project at Stanford, which has received funding support by the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation. Dr. Simard is supported by a career development award from the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH NIAMS K01-AR066878).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Zandman-Goddard G, Peeva E, Rozman Z, et al. Sex and gender differences in autoimmune diseases. In: Oertelt-Prigione S, Regitz-Zagrosek V, eds. Sex and gender aspects in clinical medicine. London: Springer-Verlag London, 2012:101–124 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman CH, Hiraki LT, Liu J, et al. Epidemiology and sociodemographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis among US adults with Medicaid coverage, 2000–2004. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:753–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aranow C, Diamond B, Mackay M. 51: Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Rich R, Fleisher T, Shearer W, Schroeder H, Frew A, Weyand C, eds. Clinical immunology: Principles and practice. New York, NY: Elsevier, 2008:749–766 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yacoub Wasef SZ. Gender differences in systemic lupus erythematosus. Gend Med 2004;1:12–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costenbader KH, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Karlson EW. Reproductive and menopausal factors and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in women. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1251–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crosslin KL, Wiginton KL. Sex differences in disease severity among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Gend Med 2011;8:365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrade RM, Alarcón GS, Fernández M, et al. Accelerated damage accrual among men with systemic lupus erythematosus: XLIV. Results from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:622–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy G, Isenberg D. Effect of gender on clinical presentation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2013;52:2108–2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman CH, Hiraki LT, Winkelmayer WC, et al. Serious infections among adult Medicaid beneficiaries with systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1577–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boodhoo KD, Liu S, Zuo X. Impact of sex disparities on the clinical manifestations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine 2016;95:e4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartzman-Morris J, Putterman C. Gender differences in the pathogenesis and outcome of lupus and of lupus nephritis. Clin Dev Immunol 2012;2012:604892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu L-J, Wallace DJ, Ishimori ML, Scofield RH, Weisman MH. Review: Male systemic lupus erythematosus: A review of sex disparities in this disease. Lupus 2010;19:119–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartels CM, Buhr KA, Goldberg JW, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in a US population-based cohort. J Rheumatol 2014;41:680–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merola JF, Bermas B, Lu B, et al. Clinical manifestations and survival among adults with (SLE) according to age at diagnosis. Lupus 2014;23:778–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez-Puerta JA, Barbhaiya M, Guan H, Feldman CH, Alarcón GS, Costenbader KH. Racial/ethnic variation in all-cause mortality among United States Medicaid recipients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A Hispanic and Asian paradox. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:752–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mok CC, Kwok RCL, Yip PSF. Effect of renal disease on the standardized mortality ratio and life expectancy of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2154–2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y-M, Lin C-H, Chen H-H, et al. Onset age affects mortality and renal outcome of female systemic lupus erythematosus patients: A nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Rheumatology 2014;53:180–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lerang K, Gilboe I-M, Steinar Thelle D, Gran JT. Mortality and years of potential life loss in systemic lupus erythematosus: A population-based cohort study. Lupus 2014;23:1546–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas G, Mancini J, Jourde-Chiche N, et al. Mortality associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in France assessed by multiple-cause-of-death analysis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2503–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souza DCC, Santo AH, Sato EI. Mortality profile related to systemic lupus erythematosus: A multiple cause-of-death analysis. J Rheumatol 2012;39:496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: A comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine 2003;82:299–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Holmberg SD. Causes of death and characteristics of decedents with viral hepatitis, United States, 2010. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:40–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Palmer C. Healthcare cost and utilization project—HCUP a federal-state-industry partnership in health data Clinical Classifications Software (CCS). 2015. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf Accessed July18, 2016

- 24.McMurray RW, May W. Sex hormones and systemic lupus erythematosus: Review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2100–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simard JF, Sjöwall C, Rönnblom L, Jönsen A, Svenungsson E. Systemic lupus erythematosus prevalence in Sweden in 2010: What do national registers say? Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1710–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doria A, Iaccarino L, Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Turriel M, Petri M. Cardiac involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2005;14:683–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huong DL, Papo T, Beaufils H, et al. Renal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. A study of 180 patients from a single center. Medicine 1999;78:148–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somers EC, Marder W, Cagnoli P, et al. Population-based incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: The Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance program. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:369–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hepburn AL, Narat S, Mason JC. The management of peripheral blood cytopenias in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2010;49:2243–2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasidharan PK, Bindiya M, Sajeeth Kumar KG. Systemic lupus erythematosus—A hematological problem. J Blood Disord Transfus 2013;4:168 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wise E, McCune J. Racial disparities result in unprecedented differences in outcomes for SLE patients. Rheumatol 2015. Available at: www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/racial-disparities-in-outcome-for-sle-patients-are-unprecedented Accessed September5, 2017

- 32.Calvo-Alén J, Alarcón GS, Campbell R, Fernández M, Reveille JD, Cooper GS. Lack of recording of systemic lupus erythematosus in the death certificates of lupus patients. Rheumatology 2005;44:1186–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]