Abstract

Study Objectives:

Subjective versus objective sleepiness in heart failure (HF) remains understudied; therefore, we sought to examine the association of these measures and interrelationships with biochemical markers.

Methods:

Participants with stable systolic HF recruited from a clinic-based program underwent attended polysomnography, Multiple Sleep Latency Testing, questionnaire data collection including Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and morning phlebotomy for biochemical markers. Linear regression was used to assess the association of mean sleep latency (MSL) and ESS (and other reported outcomes) with adjustment of age or body mass index or left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (beta coefficients, 95% confidence interval) and also with biochemical markers (beta coefficients, 95% confidence interval).

Results:

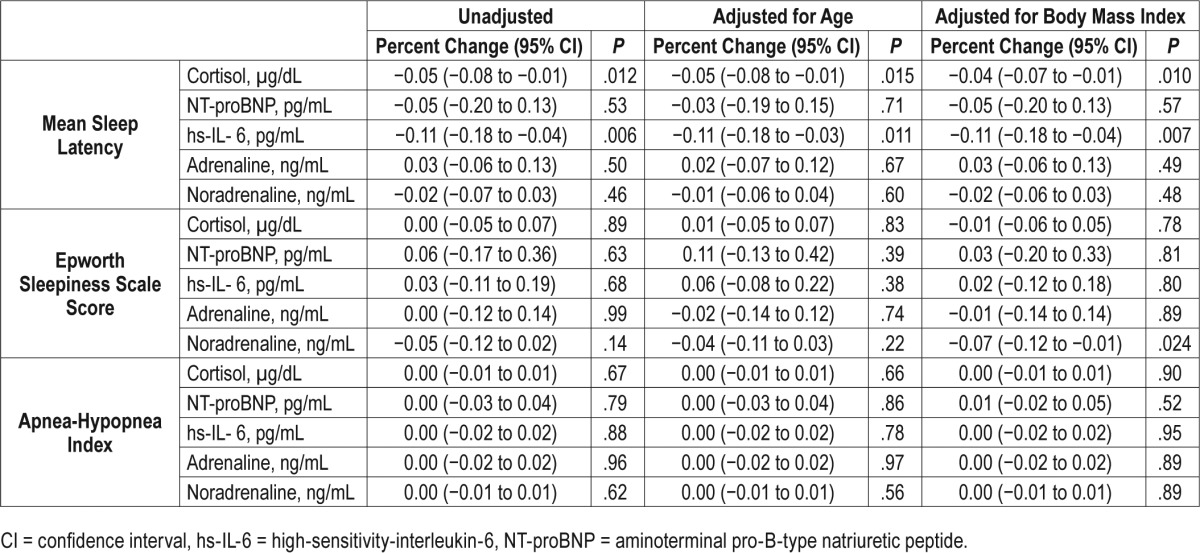

The final analytic sample comprised 26 participants: 52 ± 14 years with apnea-hypopnea index (AHI): 34 ± 27, LVEF: 34 ± 12%, MSL: 7 ± 5 minutes and ESS: 7 (5, 10). There was no significant association of MSL and ESS (−0.36, −0.81 to 0.09, P = .11), AHI, or other questionnaire-based outcomes in adjusted analyses. Although statistically significant associations of ESS and biomarkers were not observed, there were associations of MSL and cortisol (μg/dL) [−0.05: −0.08, −0.01, P = .012] and interleukin-6 (pg/mL) [−0.11: −0.18, −0.04, P = .006], which persisted in adjusted models.

Conclusions:

In systolic HF, although overall objective sleepiness was observed, this was not associated with subjective sleepiness (ie, a discordance was identified). Differential upregulation of systemic inflammation in objective sleepiness was observed, findings not observed with subjective sleepiness. These findings suggest that underlying mechanistic pathways of inflammation may provide the explanation for dissonance of objective and subjective sleepiness symptoms in HF, thus potentially informing targeted diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Commentary:

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 1369.

Citation:

Mehra R, Wang L, Andrews N, Tang WH, Young JB, Javaheri S, Foldvary-Schaefer N. Dissociation of objective and subjective daytime sleepiness and biomarkers of systemic inflammation in sleep-disordered breathing and systolic heart failure. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(12):1411–1422.

Keywords: biomarkers, heart failure, sleep apnea, sleepiness, systemic inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), a term used to characterize a range of obstructive and central sleep apneas, is a common disorder associated with a host of adverse health sequelae. Population-based data indicate that the prevalence of SDB continues to increase over the past several decades, with most recent estimates of 9% and 17% for women and men, respectively, using standard polysomnography (PSG)-based definitions.1 In particular, a wealth of data have amassed, underscoring the high prevalence of SDB in both reduced and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) heart failure (HF)—arguably with data most evident and consistent in systolic HF populations.2–4 SDB represents an important yet underrecognized comorbidity in HF, with prevalence estimates of 50% to 75% of moderate to severe levels of SDB in primarily clinic-based studies.4,5 Despite therapeutic advancements in HF prevention and treatment paradigms, chronic systolic HF is estimated to occur in 2% to 3% of the population and is associated with increased hospitalizations and consequent increased health care costs as well as increased mortality.6 Systolic HF is associated with a poor prognosis underscored by data indicating that 50% of HF participants die within 4 years and half of those with severe HF die within 1 year.7

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: The basis for conducting this work is to characterize the inter-relationships of objective and subjective sleepiness and associations with sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and circulating biomarkers of systemic inflammation in patients with systolic heart failure. Understanding the perception of sleepiness relative to objective sleepiness measures remains an existing knowledge gap that needs to be addressed to inform not only SDB screening and diagnostic approaches in heart failure, but also potentially treatment responsiveness.

Study Impact: We observed novel findings of lack of association (ie, a discordance of measures of objective and subjective sleepiness in systolic heart failure and differential increases in biomarkers of systemic inflammation associated with objective, but not subjective, sleepiness measures). These results are of scientific significance because there are potential clinical implications that need to be verified in larger studies of predictive biochemical signatures discerning physiologic from behavioral sleepiness and also a possible role for screening for sleep disruption and treatment responsiveness in systolic heart failure.

Given the high-level morbidity and mortality associated with systolic HF and data demonstrating that SDB increases HF readmission rates8 and is associated with increased post-discharge mortality in acute HF,9 there is an urgent need to identify factors such as SDB that can mitigate adverse health consequences in HF. A unique challenge to the identification of SDB in HF, however, is that common SDB signs and symptoms such as snoring, fatigue, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and nocturia are often considered attributable to HF pathophysiology and/or medication effects rather than SDB. Furthermore, rather than hypersomnia, those with systolic HF are likely to present with sleep maintenance insomnia—perhaps attributable to the heightened sympathetic activation intrinsic to HF— which may represent a risk or harbinger of HF development or progression.10 A well-recognized symptom of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in general terms is the complaint of excessive daytime sleepiness, which is a major reason for referral for diagnostic sleep testing. In the general population, subjective daytime sleepiness has been shown to correlate with objective measures of sleepiness.11,12 Although the interrelationships of measures of objective and subjective sleepiness have been examined in previously published work involving individuals with systolic HF and central sleep apnea,13–15 there are no reports of systematic investigation of characterizing sleepiness measures in HF and OSA. Moreover, although biomarkers of systemic inflammation such as interleukin-6 have been implicated in fatigue and sleepiness and others such as cortisol associated with a hyperarousal state promoting vigilance, these markers have not been studied in relation to objective and subjective sleepiness in SDB and HF.16,17

Understanding subjective perception of sleepiness relative to objective sleepiness measures remains an understudied area of key importance to inform not only SDB screening and diagnostic approaches in HF, but also potentially treatment responsiveness. We therefore conducted a prospective, clinic-based investigation focused on participants with systolic HF to examine the following: (1) the extent by which the subjective perception of sleepiness (ie, dozing propensity) corresponds to objective daytime sleepiness ascertained by the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), (2) the association of objective sleepiness and SDB severity, sleep architecture and participant reported outcomes, and (3) the associations of biochemical markers implicated in HF and SDB pathophysiology.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-six adults older than 18 years with stable chronic HF (no change in clinical status ≥ 3 months) evaluated in the Cleveland Clinic Heart Failure Center were recruited without prior knowledge of sleep disorder symptoms. Exclusion criteria included the prior diagnosis of OSA or central sleep apnea, current treatment for SDB, HF due to primary valvular disease, congenital heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, stroke or neuromuscular disease, cardiac transplantation significant neurologic disease including stroke of neuromuscular disease, and pregnancy. The study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board (#05-035) and participants signed informed consent prior to the initiating study procedures.

Data Collection

Polysomnography

Attended, overnight PSG was performed using the Nihon Kohden (Tokyo, Japan) system including electroencephalography (C3-M2, O1-M2, C4-M1, O2-M1), bilateral electrooculography, continuous airflow with thermistor and nasal pressure transducer, thoracic and abdominal respiratory inductance plethysmography, body position, submental and bilateral anterior tibial electromyography, end-tidal CO2 monitoring, and finger pulse oximetry. Respiratory events were scored according to standard criteria in place at the time of data acquisition.18 Hypopnea was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in the nasal pressure signal for at least 10 seconds associated with a ≥ 3% oxygen desaturation or an arousal. Central apnea was defined as the absence of airflow and thoracoabdominal excursions for 10 seconds or more. If thoracoabdominal excursions were present, the apnea was scored as obstructive.

Biochemical Marker Collection and Analyses

Fasting morning venipuncture was performed subsequent to the PSG and prior to the MSLT study. One serum sample tube (10 cc) and 1 ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube for plasma (10 cc) was collected and transferred on ice within 2 hours for processing and storage in dedicated, alarmed freezers at −80°C. The following biochemical markers were examined based on existing literature identifying these measures involved in underlying mechanistic pathways of SDB or HF.19–22 Cortisol (μg/dL) was measured using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay performed on a Roche Cobas e411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana, United States) with validation studies on pooled human samples demonstrating a repeatability coefficient of variation (CV) < 1.5% and precision CV < 2.0%. Aminoterminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) (pg/mL) was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay performed on a Roche Cobas e411 analyzer with validation studies on pooled human samples demonstrating a repeatability CV < 5% and precision CV < 5%. High-sensitivity-interleukin-6 (hs-IL-6, pg/mL) was measured using a quantitative enzyme sandwich immunoassay (ie, a 96-well Quantikine Elisa by R&D Systems [Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States]) with an average intra-assay precision CV < 8% and interassay precision a CV < 10%. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha was measured using a quantitative enzyme sandwich immunoassay (ie, a 96-well Quantikine Elisa by R&D Systems) with an average intra-assay precision CV < 6% and inter-assay precision a CV < 8%. Adrenaline (ng/mL) and noradrenaline (ng/mL) were measured using 96-well Competitive Elisa by Abnova (Abnova, Taiwan) with an average intra-assay precision CV < 13% and interassay precision a CV < 13% and < 10%, respectively.

Multiple Sleep Latency Testing

The MSLT is widely regarded as the gold standard for objective ascertainment of daytime sleepiness to assess physiologic daytime sleepiness propensity. The MSLT studies (electroencephalogram, electrooculogram, and electromyography) were performed the morning following the PSG (within 1.5–3 hours of morning of termination of the nocturnal recording) and consisted of 5 nap trials at 2-hour intervals according to standard guidelines.23,24 The participant went to bed at the usual time the night prior. The participants were asked to wear comfortable, nonrestrictive street clothes and to have a light breakfast 1 hour prior to the first trial and a light lunch immediately after the termination of the second noon trial. Participants were continuously monitored to verify lack of sleep between the naps, not permitted to have caffeine or alcohol during the test, and instructed to avoid smoking for 30 minutes prior to each trial, avoid vigorous exercise for 15 minutes prior to each trial, avoid sleeping in between trials, and avoid unusual exposures to bright sunlight. Lights were dimmed to off and the participant was instructed to lie quietly, keep eyes closed, and try to rest. The time to sleep onset (sleep latency) for each nap was defined as the time from the beginning of the recorded nap to the initial 30-second epoch of any stage of sleep. Participants then slept for 15 minutes after sleep onset to assess for REM periods or if sleep was not achieved, the recording was terminated after 20 minutes. Mean sleep latency (MSL) was calculated across naps and sleep onset REM periods were noted. MSL averaged across the naps and a value of less than 8 minutes was considered an indication of objective physiologic sleepiness as per standard guidelines.25

Subjective Assessment of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness

The instrument used to ascertain subjective sleepiness was the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). The ESS is a self-administered 8-item questionnaire that measures an individual's subjective daytime dozing propensity. Subjects were asked how likely they are to doze off or fall asleep in 8 specific situations (never, slight, moderate, high: 0–3), with total scores ranging from 0–24. Scores higher than 10 are considered indicative of subjective excessive daytime somnolence.26 The ESS is a well-valuated and reliable instrument and has been used in sleep research. A score higher than 10 has a sensitivity of approximately 94% and specificity of 100% to distinguish pathologic from normal in treated and untreated participants with narcolepsy and was used in this study to define clinically relevant daytime sleepiness.27

Participant-Reported Outcomes

Other patient-reported outcomes included the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) and the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) The FSS is a 9-item Likert-type scale from 1 to 7, where 1 indicates no impairment and 7 indicates severe impairment.28 Validation work supports its use as a simple and reliable instrument to assess and quantify fatigue for clinical and research purposes.29 Responses to individual items are totaled to produce an FSS score. In the initial validation study, the mean FSS score for normal healthy adults was 2.3 (standard deviation [SD] 0.7). It distinguished between participants with a chronic disease such as multiple sclerosis (mean 4.8, SD 1.5) and controls with a high internal consistency and test-retest reliability.28 The FOSQ is a 30-item Likert-style questionnaire measuring functional status, a component of quality of life, as it relates to the effect of excessive daytime sleepiness or being tired during daily activities (including activity level, vigilance, intimacy and sexual relationships, general productivity, and social outcome). Global and subscale scores are produced and a global score higher than 18 is considered normal.30

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (25th, 75th percentiles) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. For comparison of demographic characteristics and PSG measures between groups by apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) cutoff, t test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used in continuous variables, Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. Linear regression models were used to assess the association between MSL and ESS with and without adjustment of age or body mass index or LVEF. Separate models were examined for MSL and FSS, FOSQ, and AHI. Beta coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to examine the correlation of MSL, ESS, and SDB severity and the biochemical markers. The association of biochemical markers and MSL, ESS, and SDB severity was also assessed by using linear regression models adjusted separately for age or body mass index. Logarithmic transformation was performed prior to analysis. Coefficients from linear models were transformed back to show the percent change of biomarkers when predictors per 1-unit increase. As TNF-alpha levels were highly skewed, model assumptions were not met to perform regression analyses. SAS version 9.4 (The SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States) was used to perform all analyses.

RESULTS

Overall Sample Description

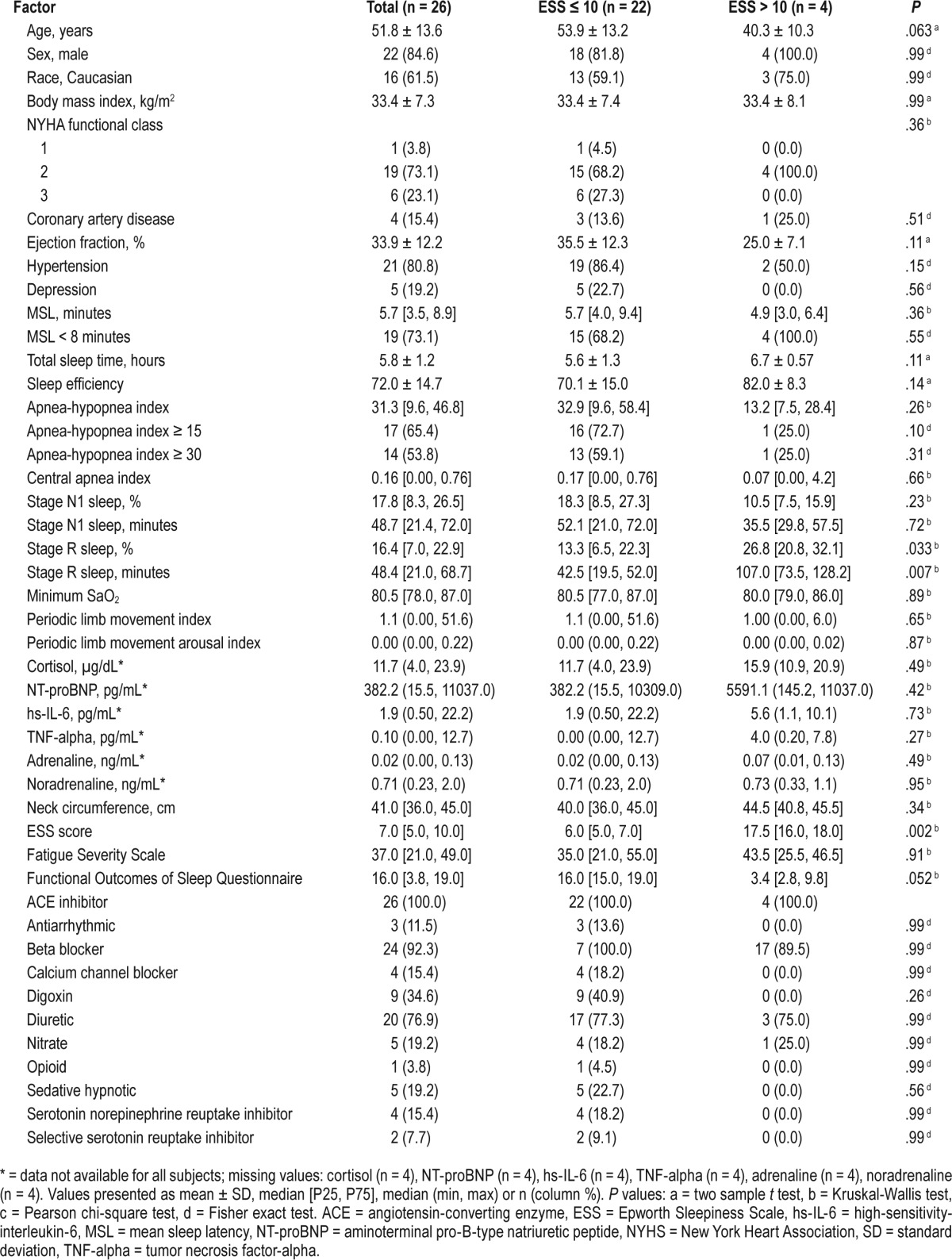

Of 26 participants with systolic heart failure enrolled in the research study, n = 17 (65%) had an AHI ≥ 15 and n = 15 (54%) had a severe degree of SDB (ie, AHI ≥ 30). The overall cohort was middle-aged, with a high percentage of males who were obese (body mass index = 33.4 ± 7.3 kg/m2) and with LVEF = 33.9 ± 12.2%. Those with moderate to severe SDB had increased percentage and time in minutes of stage N1 sleep and reduced stage R sleep time in minutes. The overall cohort had a pathologic degree of objective sleepiness with MSL of 5.7 (3.5, 8.9) minutes; however, the overall ESS was within normal range: 7.0 (5.0, 10.0). Of note, those with moderate to severe SDB (AHI ≥ 15) had a significantly lower ESS compared to those with an AHI < 15 (6.0 [4.0, 7.0] versus 10.0 [6.0, 15.0] respectively, P = .039); however, there was no statistically significant difference in objective sleepiness measured by the MSL (5.1 [3.5, 8.9] versus 6.4 [5.7, 7.8], P = .27) across these SDB categories (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics by MSL.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics by ESS score.

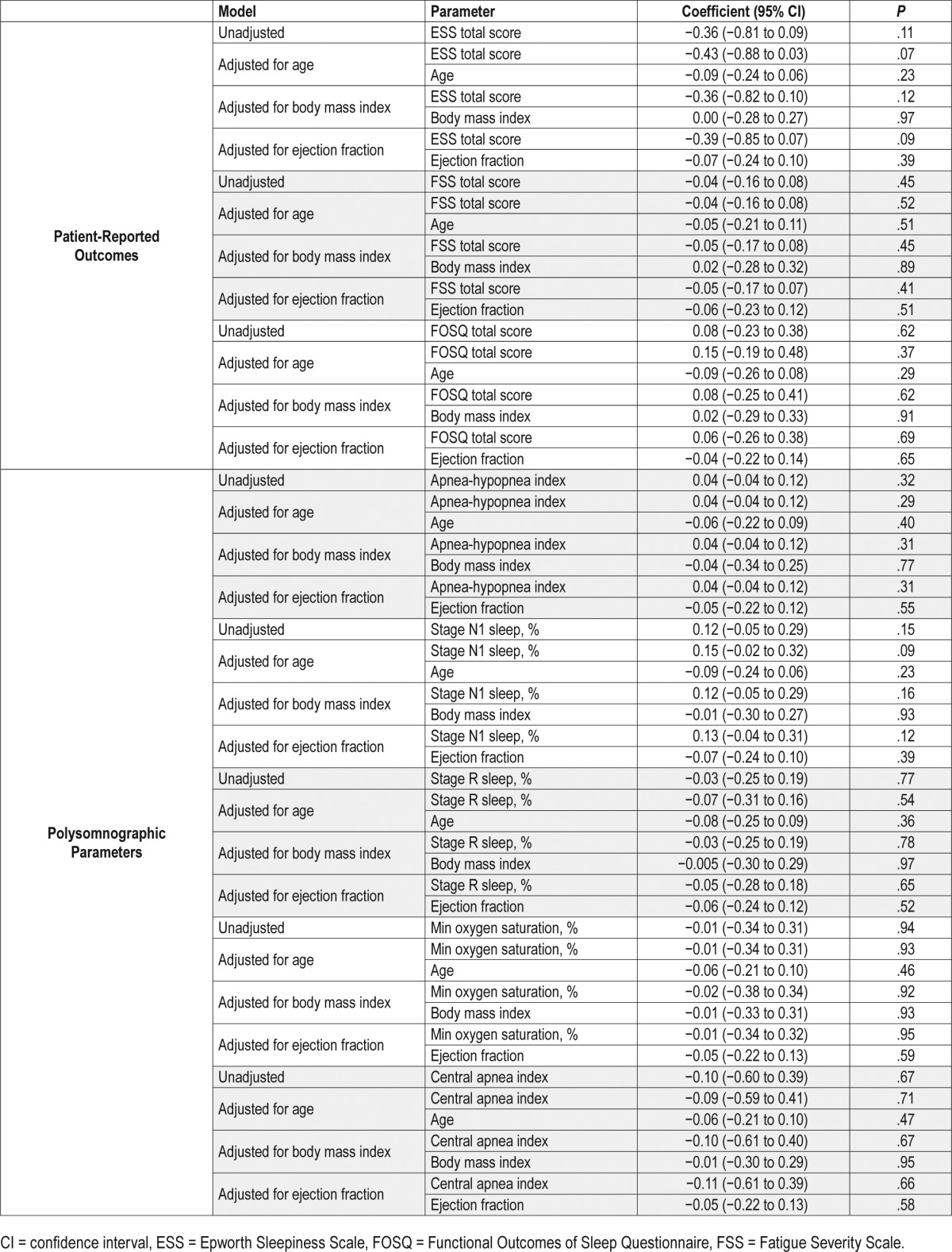

Association of Objective Sleepiness and Subjective Sleepiness and Other Patient-Reported Outcomes

In the linear model, there was a non-statistically significant negative association of objectively ascertained sleepiness measured via MSL from the MSLT and the ESS score reflecting subjective sleepiness (beta coefficient = −0.36, 95% CI: −0.81 to 0.09). This lack of significant association persisted after adjustment for age and separately when adjusted for LVEF. Similarly, there was no significant association of the MSL and FSS (beta coefficient = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.16 to 0.08) and FOSQ (beta coefficient = 0.08, 95% CI: −0.23 to 0.38) scores. There was also no association of the MSL across moderate to severe SDB categories and these findings were consistent across all of the naps (Table 3).

Table 3.

Linear regression models of patient-reported outcomes and polysomnographic parameters in relation to mean sleep latency.

Association of Objective Sleepiness and Polysomnographic Parameters

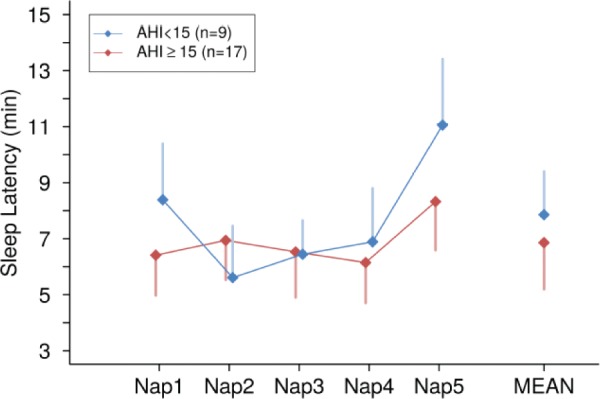

No statistically significant association was observed with MSL and SDB measures (ie, AHI [beta coefficient = 0.04, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.12], central apnea index [beta coefficient = −0.10, 95% CI −0.60 to 0.39], and minimum oxygen saturation [beta coefficient = −0.01, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.31]). There were no significant differences of MSL across SDB categories (Figure 1). Similarly, there were no significant associations of MSL and sleep architecture parameters (percentage of stage R sleep: beta coefficient −0.03, 95% CI −0.25 to 0.19) and percentage of stage N1 sleep: beta coefficient 0.12, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.29) (Table 3).

Figure 1. Sleep onset latency across multiple sleep latency naps across moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea category.

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index.

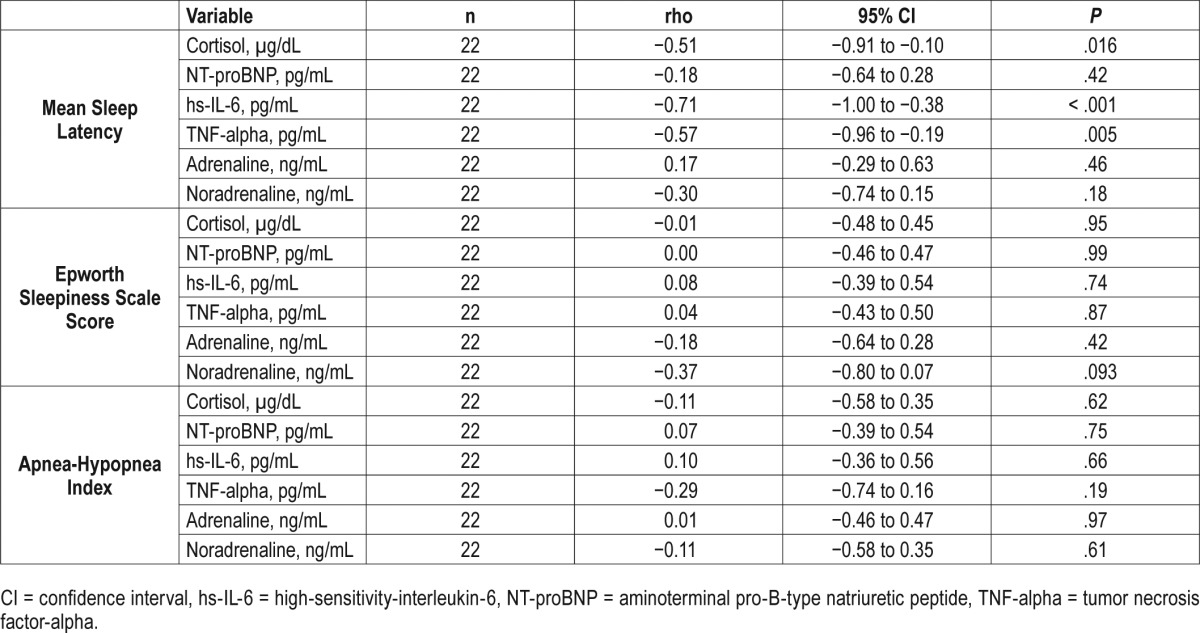

Association of Biochemical Markers and Sleepiness Parameters

Of the 22 participants with blood samples (n = 4 declined), significant associations of markers of systemic inflammation were observed with the MSL, but not with degree of subjective sleepiness (ESS) or SDB severity (AHI). When calculating the Spearman correlation coefficients, significant correlations of MSL and cortisol, hs-IL-6, and TNF-alpha were identified (Table 3). In the linear models, statistically significant inverse associations were observed such that for every minute reduction in the MSL, there was a 5% unit increase in cortisol (−0.05, 95% CI: −0.08 to −0.01, P = .012) and an 11% increase in hs-IL-6 (−0.11, 95% CI: −0.18 to −0.04, P = .006) (Table 4, Table 5, Figure 2).

Table 4.

Spearman correlation of sleepiness measures and sleep-disordered breathing severity with biomarkers of systemic inflammation in systolic heart failure.

Table 5.

Linear regression models of sleepiness measures and sleep-disordered breathing severity with biomarkers of systemic inflammation in systolic heart failure.

Figure 2. Correlation of objective sleepiness defined by mean sleep latency on Multiple Sleep Latency Testing and biomarkers.

hs-IL-6 = high-sensitivity-interleukin-6, TNF-alpha = tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

DISCUSSION

This study is the most systematic and detailed examination of interrelationships of subjective and objective sleepiness indices and biochemical markers of systemic inflammation in systolic HF and SDB. In this middle-aged, predominantly male, obese sample, we identified an overall pathologic degree of objective sleepiness (85% of the sample with MSL < 10 minutes) in the absence of overall enhanced subjective perception of sleepiness or dozing propensity. We report a dissociation between objective and subjective daytime sleepiness in participants with systolic HF after separate consideration of confounding by age, body mass index, and ejection fraction. In those with moderate to severe SDB, self-reported sleepiness scores are lower (indicating less dozing propensity) compared to those with lesser degree of or without SDB. There were no signifi-cant associations of objective sleepiness and patient-reported outcomes, SDB measures, or sleep architecture parameters. A significant association of increasing objective sleepiness (reduction of MSL) and increasing levels of systemic biomarkers of inflammation was also observed, providing a potential mechanistic explanation for the objective-subjective sleepiness discordance.

It is clinically widely recognized that those with HF do not subjectively report daytime sleepiness despite the high prevalence of comorbid SDB and associated sleep disruption. For example, in one of the largest clinical trials involving participants with SDB and reduced ejection fraction HF, the overall approximate average ESS was 7, which is consistent with findings of our current work.31 Case finding and commonly used screening instruments for OSA such as the Berlin Questionnaire and STOP-Bang questionnaires that incorporate sleepiness/tiredness therefore are limited in the ability to accurately establish pretest probability for sleep apnea in systolic HF. Our findings, however, suggest that objective sleepiness measures are pathologically abnormal, indicating a disconnect and a potential sleepiness perception issue, thereby underscoring the seemingly complex sleep-wake pathophysiology in HF. It bears mention that objective measures of MSL and ESS are modestly negatively correlated in previously published data (ie, higher ESS scores and lower MSL with correlations ranging from 0.3–0.5 consistent with the strength of association replicated in the current work).32 A potential explanation for the lack of higher agreement is the assessment of sleepiness propensity in a single situation for the MSLT and evaluating 8 different situations of sleepiness for the ESS and possibly perception of sleepiness or sympathetic activation. However, this discrepancy appears to be pronounced and demonstrates reverse directionality in systolic HF according to the current findings (ie, overall lower ESS and higher MSL). Furthermore, more recent data utilizing survival analytic techniques identified a clearly apparent association of ESS and MSL characteristics in a clinic-based sample not selected for HF, which was consistent across the individual ESS questions and independent of several participant characteristics.11 Our findings therefore suggest more pronounced alterations in the objective neurophysiologic state in systolic HF that is not being reflected in subjective behavioral sleepiness propensity.

Although no prior studies have been designed to examine objective and subjective sleepiness measures in obstructive and central SDB in systolic HF, there are several that have examined these relationships in central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respirations (CSR). The first of these studies was focused on investigation of CSR and excessive daytime sleepiness in 23 male patients (n = 7 with CSR) with the a priori hypothesis that nocturnal hypoxemia and sleep fragmentation association with CSR would increase likelihood of associated sleepiness.14 A discrepancy of subjective and objective sleepiness (the latter measured via MSLT) was observed such that patients with CSR had an average normal ESS and abnormal MSL (4 ± 1.1 minutes), a finding not observed in HF patients without CSR nor in healthy controls.14 Our findings in a sample of systolic HF with a high prevalence of OSA have yielded similar findings, suggesting aberrations in sleepiness physiology irrespective of SDB type. In a separate study involving 22 patients with mild to moderate systolic HF, abnormalities of the Oxford Sleep Resistance Test (a behavioral objective test of sleepiness that simplifies the performance of the maintenance of wakefulness test) were identified in those with moderate to severe SDB, but not in those without or with lesser degree of SDB and occurred in the absence of overall subjective sleepiness.33 Our findings are similar, except this discordance was observed in the entire group and not limited to those with moderate to severe SDB. Finally, a study of 30 participants of a clinical trial with CSR and systolic HF identified improvement in objective sleepiness measures (ie, Oxford Sleep Resistance Test) but not subjective sleepiness in response to adaptive servoventilation, implying neurobehavioral sleepiness treatment responsiveness.34

The novelty of this study lies not only with the investigation of objective and subjective sleep parameters in a systolic HF and SDB (and not isolated central sleep apnea or CSR), but also in the examination of the potential role of biochemical markers. We identified a significant correlation of increased levels of specific cytokines (TNF-alpha and hs-IL-6) and MSL reduction, the latter indicating more pronounced objective sleepiness, findings not observed with subjective sleepiness. Experimental studies have highlighted the somnogenic and sleep regulatory properties of TNF-alpha. For instance, exogenous TNF-alpha administration induces increases in non-rapid eye movement sleep—and specifically slow wave sleep—in various animal models with onset rapidly occurring within the first hour postinjection.35,36 Moreover, inhibition of endogenous TNF-alpha attenuates various sleep responses, including physiological sleep measures.37,38 It is important to note that these results should be interpreted with caution because of the substantial skewed nature of the data. Alternatively, IL-6 has been recognized as a pyrogenic but not somnogenic cytokine,39 and has been implicated in increased cardiovascular morbidity40 and short- and long-term mortality in acute HF.41 Consistent with our findings, the increase in IL-6 in relation to objective but not subjective sleep measures has been recently described in a sleep clinic-based group of patients with OSA whereby the authors purported that objective sleepiness therefore serves as an indicator of a more reliable phenotype of cardiovascular risk.16 Results from other studies also show associations of increased IL-6 levels and sleep disruption.16,42,43 Unlike our findings, however, in this study, decreased cortisol levels were related to increased objective sleepiness, which contrasts with our finding of increases in cortisol with increased objective sleepiness.16 These differences may be attributable to different patient populations (eg, in chronic HF, increasing cortisol levels predict incident cardiac events).44 Other potential reasons for differences in findings may be due to 24-hour patterning of cortisol levels given the recognized circadian secretory patterns, variation in the quality of sleep the night prior to the blood level collection, and possible cortisol-mediated upregulation of counterregulatory somnogenic cytokine pathways. The lack of observed increase in adrenaline and noradrenaline with reduction in objective sleepiness may be due to the overwhelming enhanced sympathetic state in HF or perhaps insufficient power to detect an association.

The strengths of the study include the careful, standardized collection of sleep physiologic, patient-reported outcome and blood biomarker data. Although the sample size is small, it appears that we were powered sufficiently to appreciate significant associations of interest, particularly with the biomarkers. We cannot exclude residual confounding of observed associations from visceral adiposity and did not examine 24-hour patterning of the biochemical measures. None of the patients had ongoing infections or underlying autoimmune disease or reported taking psychotropic medications, steroids, sympathomimetics, or sympatholytics or hormone replacement therapy that could have affected the findings. Although multiple comparisons were made, we view the current study and findings as preliminary and exploratory requiring further verification in larger studies. These results are potentially clinically relevant and set the stage for these larger confirmatory studies. The biologic basis of the discrepancy in subjective and objective sleepiness in systolic HF and SDB remains unclear, however, given our findings of a differential increase in cortisol and hypercytokinemia with somnogenic culprits such as TNF-alpha and increases in objective sleepiness, dysregulation of these pathways represents a viable potential mechanistic explanation. Future investigation should be focused on characterization of the potential clinical implications of predictive biochemical signatures discerning physiologic from behavioral sleepiness in systolic HF and for utility in screening for sleep disruption and treatment responsiveness.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have viewed and approved the submitted manuscript. Dr. Mehra has received NIH funding for which she has served as Principal Investigator (NHLBI R01 1 R01 HL 109493). Dr. Mehra serves as a standing member on an NIH study section for which she receives an honorarium. Her institution has received positive airway pressure machines and equipment from Philips Respironics and Resmed for research purposes. She serves as the Associate Editor for the journal Chest. She has received royalties from Up to Date and honorarium from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Dr. Foldvary-Schaefer has received research funding from the Clinical Translational Science Collaborative and Resmed. Dr. Tang has received NIH funding for which he has served as Principal Investigator (R01 HL103931). Dr. Javaheri is a consultant for Respicardia, Philips, and Leva Nova Group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all of the participants, laboratory personnel, and sleep medicine technical staff who assisted with data collection for this study, including Alan Pratt.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- CI

confidence interval

- CSR

Cheyne-Stokes respirations

- CV

coefficient of variation

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FOSQ

Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire

- FSS

Fatigue Severity Scale

- HF

heart failure

- hs-IL-6

high-sensitivity-interleukin-6

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MSL

mean sleep latency

- MSLT

Mean Sleep Latency Test

- NREM

non-rapid eye movement

- NT-proBNP

aminoterminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- REM

rapid eye movement

- SD

standard deviation

- SDB

sleep-disordered breathing

- TNF-alpha

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

REFERENCES

- 1.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(9):1006–1014. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan J, Sanderson J, Chan W, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in diastolic heart failure. Chest. 1997;111(6):1488–1493. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Javaheri S, Barbe F, Campos-Rodriguez F, et al. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(7):841–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldenburg O, Lamp B, Faber L, Teschler H, Horstkotte D, Topfer V. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a contemporary study of prevalence in and characteristics of 700 patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(3):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz R, Blau A, Börgel J, et al. Sleep apnoea in heart failure. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(6):1201–1205. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00037106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(8):803–869. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi PU, Pinney S. Management of chronic heart failure: biomarkers, monitors, and disease management programs. Ann Glob Health. 2014;80(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khayat R, Abraham W, Patt B, et al. Central sleep apnea is a predictor of cardiac readmission in hospitalized patients with systolic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18(7):534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khayat R, Jarjoura D, Porter K, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and post-discharge mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(23):1463–1469. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laugsand LE, Strand LB, Platou C, Vatten LJ, Janszky I. Insomnia and the risk of incident heart failure: a population study. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1382–1393. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aurora RN, Caffo B, Crainiceanu C, Punjabi NM. Correlating subjective and objective sleepiness: revisiting the association using survival analysis. Sleep. 2011;34(12):1707–1714. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30(6):711–719. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arzt M, Young T, Finn L, et al. Sleepiness and sleep in patients with both systolic heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(16):1716–1722. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanly P, Zuberi-Khokhar N. Daytime sleepiness in patients with congestive heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Chest. 1995;107(4):952–958. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.4.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taranto Montemurro L, Floras JS, Millar PJ, et al. Inverse relationship of subjective daytime sleepiness to sympathetic activity in patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2012;142(5):1222–1228. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, et al. Objective, but not subjective, sleepiness is associated with inflammation in sleep apnea. Sleep. 2017;40(2) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, et al. Sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness and fatigue: relation to visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and hypercytokinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(3):1151–1158. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciftci TU, Kokturk O, Bukan N, Bilgihan A. The relationship between serum cytokine levels with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Cytokine. 2004;28(2):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansfield DR, Gollogly NC, Kaye DM, Richardson M, Bergin P, Naughton MT. Controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea and heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):361–366. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-752OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmalgemeier H, Bitter T, Fischbach T, Horstkotte D, Oldenburg O. C-reactive protein is elevated in heart failure patients with central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Respiration. 2014;87(2):113–120. doi: 10.1159/000351115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshihisa A, Suzuki S, Yamaki T, et al. Impact of adaptive servo-ventilation on cardiovascular function and prognosis in heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction and sleep-disordered breathing. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(5):543–550. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Mitler MM, Roth T, Westbrook PR, Keenan S. Guidelines for the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9(4):519–524. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Littner MR, Kushida C, Wise M, et al. Practice parameters for clinical use of the multiple sleep latency test and the maintenance of wakefulness test. Sleep. 2005;28(1):113–121. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johns MW. Sensitivity and specificity of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the maintenance of wakefulness test and the Epworth sleepiness scale: failure of the MSLT as a gold standard. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(1):5–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(10):1121–1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valko PO, Bassetti CL, Bloch KE, Held U, Baumann CR. Validation of the fatigue severity scale in a Swiss cohort. Sleep. 2008;31(11):1601–1607. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weaver TE, Laizner AM, Evans LK, et al. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep. 1997;20(10):835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al. Rationale and design of the SERVE-HF study: treatment of sleep-disordered breathing with predominant central sleep apnoea with adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(8):937–943. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chervin RD. The multiple sleep latency test and Epworth sleepiness scale in the assessment of daytime sleepiness. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(4):399–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.0227a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hastings PC, Vazir A, O'Driscoll DM, Morrell MJ, Simonds AK. Symptom burden of sleep-disordered breathing in mild-to-moderate congestive heart failure patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):748–755. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00063005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pepperell JC, Maskell NA, Jones DR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of adaptive ventilation for Cheyne-Stokes breathing in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(9):1109–1114. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200212-1476OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapas L, Hong L, Cady AB, et al. Somnogenic, pyrogenic, and anorectic activities of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and TNF-alpha fragments. Am J Physiol. 1992;263(3 Pt 2):R708–R715. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.3.R708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoham S, Davenne D, Cady AB, Dinarello CA, Krueger JM. Recombinant tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 enhance slow-wave sleep. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(1 Pt 2):R142–R149. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.1.R142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi S, Fang J, Kapas L, Wang Y, Krueger JM. Inhibition of brain interleukin-1 attenuates sleep rebound after sleep deprivation in rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(2 Pt 2):R677–R682. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.2.R677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi S, Tooley DD, Kapas L, Fang J, Seyer JM, Krueger JM. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor in the brain suppresses rabbit sleep. Pflugers Arch. 1995;431(2):155–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00410186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opp M, Obal F, Jr, Cady AB, Johannsen L, Krueger JM. Interleukin-6 is pyrogenic but not somnogenic. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Manolagas SC, Chrousos GP. The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(2):127–137. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pudil R, Tichy M, Andrys C, et al. Plasma interleukin-6 level is associated with NT-proBNP level and predicts short- and long-term mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2010;53(4):225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devine JK, Wolf JM. Integrating nap and night-time sleep into sleep patterns reveals differential links to health-relevant outcomes. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(2):225–233. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang S, Ryu S, Jeon B. Roles of the superoxide dismutase SodB and the catalase KatA in the antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter jejuni. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2013;66(6):351–353. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamaji M, Tsutamoto T, Kawahara C, et al. Serum cortisol as a useful predictor of cardiac events in patients with chronic heart failure: the impact of oxidative stress. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(6):608–615. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.868513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]