Abstract

Introduction

It has been argued that as smoking prevalence declines, the remaining smokers represent a “hard core” who are unwilling or unable to quit, a process known as hardening. However, as recently shown, the general smoking population is softening not hardening (i.e., as prevalence falls more quit attempts and lower consumption among continuing smokers). People with psychological distress smoke more, so they may represent hard core smokers.

Methods

Using cross-sectional time series analysis, in 2016–2017 changes in quit attempts and cigarette consumption were evaluated over 19 years among smokers with serious psychological distress (Kessler-6 score ≥13) based on the National Health Interview Survey (1997–2015), controlling for sociodemographic variables.

Results

People with psychological distress had higher prevalence and consumed more cigarettes/day than people without distress. The percentage of those with at least one quit attempt was higher among those with psychological distress. The increase in quit attempts over time was similar among smokers in each of the distress levels. For every 10 years the OR of a quit attempt increased by a factor of 1.13 (95% CI=1.02, 1.24, p<0.05). Consumption declined by 3.35 (95% CI= −3.94, −2.75, p<0.01) cigarette/day for those with serious psychological distress.

Conclusions

Although smoking more heavily than the general population, smokers with psychological distress, like the general population, are softening over time. To improve health outcomes and increase health equity, tobacco control policies should continue moving all subgroups of smokers down these softening curves, while simultaneously incorporating appropriately tailored quitting help into mental health settings.

INTRODUCTION

The concept of hardening of the smoking population has been described as the smoking population, on average, becoming less willing to or less capable of quitting as smoking prevalence declines, implying that hard-core smokers would increasingly comprise the smoking population.1–5 However, several studies from around the world have found that softening, not hardening, is occurring.6–8 Over time, as smoking prevalence fell continuing smokers were making more quit attempts and consumed fewer cigarettes.

Because those with psychological distress smoke more,9,10 some have identified them as hard-core smokers.11,12 Nineteen years of data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) are used to examine smoking prevalence levels and the associations between (1) the proportion of smokers who made at least one quit attempt in the past 12 months and (2) the number of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) among the remaining smokers as dependent variables, and time (as smoking prevalence decreased) as the independent variable among people with different levels of psychological distress as measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6).13,14 It is hypothesized that, as with the general population and people without psychological distress, smoking patterns are softening among people with mental distress, albeit from a higher baseline than among people without distress.

METHODS

Study Sample

Annual individual level data from 19 waves of the NHIS were used, the principal survey collecting health information on the U.S. civilian and non-institutionalized population15 for 1997 through 2015 (Appendix Table 1).

Measures

A current smoker was defined as someone who has smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smokes every day or some days, a total of 118,604 in the 19 waves. Current smokers were asked how many cigarettes they smoked per day, allowing for an answer between 1 and ≥95. These smokers were asked if they had tried quitting smoking for a day or longer in the past 12 months. Those answering yes were characterized as having made a quit attempt.

The K613,14 questions included in the NHIS were used to measure psychological distress among the smokers in the survey. The K6 consists of six questions asking about the respondent’s level of feeling sad, nervous, restless, hopeless, worthless, and whether everything felt like an effort in the past 30 days. Possible answers range from none of the time, to a little, to some, to most, to all of the time. The none of the time was scored to be 0 and all of the time to be 4, the points were then summed for all six questions to obtain an aggregate score between 0 and 24. Following Prochaska et al.16 respondents were assigned to three categories: no distress (total score 0–4), moderate distress (5–12), and serious psychological distress (13–24). Out of the total of 586,509 respondents, 11,819 (2%) had missing information for at least one K6 question, which resulted in 574,690 persons for analysis (Appendix Table 1).

The sociodemographic variables in the adjusted models were: sex (male/female), age (continuous variable in years 18 to ≥85), marital status (married/living with partner, never married, widowed/divorced/separated), alcohol use (current drinker [one or more drinks in past year], former drinker [no drinks in past year], lifetime abstainer [<12 drinks in lifetime]), educational level (0–11 years of education/12 years without diploma, high school diploma/GED or equivalent, some college/associate degree, bachelor degree and higher), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic all other race groups).

Statistical Analysis

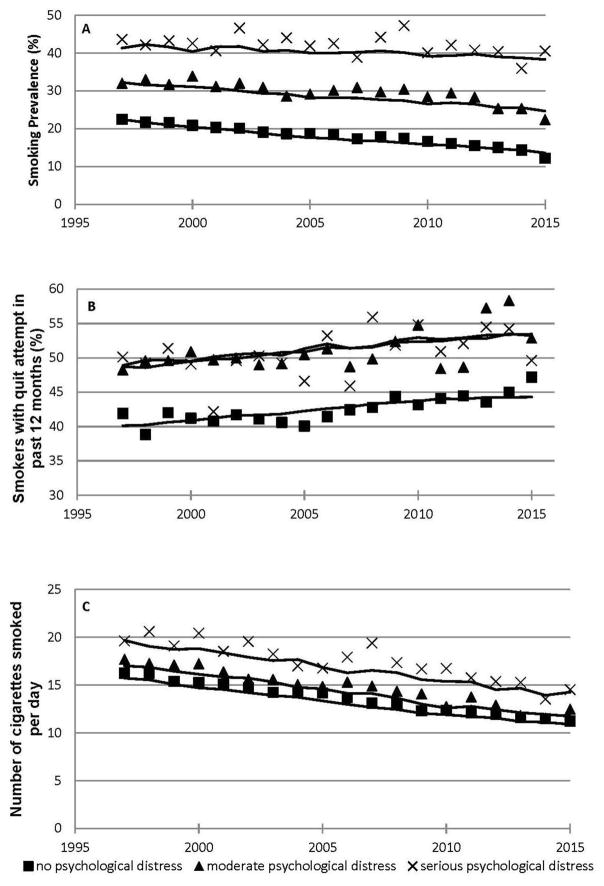

All data from the annual adult samples of the NHIS between 1997 and 2015 were pooled, accounting for the complex survey data design of the NHIS, including Primary Sampling Unit and strata17,18 for smokers in each of the three K6 categories and computed smoking prevalence, the percentage of smokers with at least one quit attempt in the past 12 months, and the number of cigarettes smoked (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Smoking prevalence declines over time, quit attempts increase, and cigarettes smoked per day decrease in those with and without psychological distress, 1997–2015.

Notes: Lines based on fitted values from adjusted regressions (details of regressions are in Appendix Table 2).

Logistic regression was used to assess changes in quit attempts and linear regression for CPD over time in unadjusted and adjusted models controlling for all sociodemographic variables. Because of collinearity between time (in 10 year increments, centered on the mean [2006]) and smoking prevalence (prevalence dropped over time, Figure 1) time was used as the independent variable in the final analysis. Analyses were run for each of the K6 categories, as well as for all smokers combined, controlling for K6 category. To assess whether time trends in quit attempts and cigarette consumption were the same in each of the distress subgroups, additional analyses were carried out for all smokers combined including interactions for decade X K6 category (Appendix Table 3).

Analysis was done with Stata, version 14 in 2016–2017.

RESULTS

Smoking prevalence declined between 1997 and 2015 for the general population and all three psychological distress groups (p<0.01 for all groups in unadjusted model), with higher prevalence among those with more psychological distress (Figure 1A; Appendix Table 2). The declines were slower among those with psychological distress (interaction terms in Appendix Table 3). Among those with serious psychological distress the unadjusted smoking prevalence fell by a factor of 0.92 (95% CI=0.86, 0.98, p<0.01) per decade, but the adjusted prevalence did not fall significantly.

The proportion of smokers with at least one quit attempt in the past 12 months increased over time in all subgroups of smokers (p<0.01 for all groups; Figure 1B and Table 1) in both the unadjusted and adjusted models. The OR of a quit attempt increases by factors of 1.39 (95% CI=1.34, 1.44) and 1.43 (95% CI=1.35, 1.53) for those with moderate and serious psychological distress compared with those without distress, respectively, in the fully adjusted model (p<0.01; Table 3). The percentage of those with at least one quit attempt is higher among those with psychological distress (Figure 1B). The increase in quit attempts over time was similar among smokers with all distress levels (interaction terms in Appendix Table 3).

Table 1.

Proportion With at Least One Quit Attempt in Past 12 months (OR and 95% CIs From Logistic Regression)

| Covariates and model fit | No psychological distress | Moderate psychological distress | Serious psychological distress | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Time (per 10 years)a | 1.12 (1.08, 1.16)** | 1.13 (1.10, 1.17)** | 1.13 (1.07, 1.20)** | 1.14 (1.08, 1.21)** | 1.12 (1.01, 1.23)* | 1.13 (1.02, 1.24)* |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.11 (1.07, 1.15)** | 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.16) | |||

| Age | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99)** | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99)** | 0.99 (0.99, 0.99)** | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/Living with partner | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Never married | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97)** | 0.95 (0.87, 1.04) | 0.84 (0.72, 0.99)* | |||

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 1.06 (0.99, 1.14) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.13) | |||

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| Current drinker | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Former drinker | 1.00 (0.95, 1.32) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.88, 1.16) | |||

| Lifetime abstainer | 0.81 (0.76, 0.87)** | 1.01 (0.91, 1.13) | 0.96 (0.78, 1.18) | |||

| Educational level | ||||||

| 0–11 years/12 years without diploma | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| HS diploma/GED or equivalent | 1.03 (0.97, 1.08) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.27)** | 1.02 (0.89, 1.17) | |||

| Some college/AA degree | 1.31 (1.24, 1.38)** | 1.30 (1.18, 1.42)** | 1.20 (1.04, 1.40)* | |||

| BA degree and higher | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36)** | 1.29 (1.14, 1.45)** | 1.28 (0.98, 1.66) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.30 (1.23, 1.37)** | 1.41 (1.28, 1.54)** | 1.50 (1.28, 1.76)** | |||

| Hispanic | 1.13 (1.06, 1.19)** | 1.20 (1.09, 1.33)** | 1.47 (1.23, 1.75)** | |||

| Non-Hispanic all other race groups | 1.14 (1.04, 1.25)** | 1.22 (1.02, 1.47)* | 1.10 (0.74, 1.62) | |||

| Constant | 0.74 (0.72, 0.75) | 1.12 (1.03, 1.21)** | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) | 1.46 (1.28, 1.67)** | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 1.39 (1.07, 1.80)* |

| Model fit p-value | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.05 | p<0.01 |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

Year centered on 2006 (−9 to 9), and divided by 10.

HS, High School; GED, General Educational Development (High School Equivalency); AA, Associate; BA, Bachelor

Table 3.

Proportion With at Least One Quit Attempt in Past 12 Months and Consumption Cigarettes/Day in the Entire Sample

| Covariates and model fit | Proportion with at least one quit attempt in past 12 months (Logistic regression) | Consumption cigarettes/day (Linear regression) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unadjusted | Including K-6 | Fully Adjusted | Unadjusted | Including K-6 | Fully Adjusted | |

| Time (per 10 years) a | 1.14 (1.11, 1.18)** | 1.12 (1.09, 1.16)** | 1.13 (1.10, 1.17)** | −2.91 (−3.07, −2.74)** | −3.00 (−3.16, −2.84)** | −2.89 (−3.03, −2.76)** |

| Psychological distress status: Kessler 6 scale | ||||||

| No distress (0–4 points) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Moderate psychological distress (5–12 points) | 1.41 (1.36, 1.47)** | 1.39 (1.34, 1.44)** | 1.17 (0.99, 1.36)** | 1.37 (1.19, 1.54)** | ||

| Serious psychological distress (13–24 points) | 1.39 (1.31, 1.48)** | 1.43 (1.35, 1.53)** | 3.89 (3.53, 4.25)** | 3.69 (3.36, 4.03)** | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1.08 (1.05, 1.12)** | −2.96 (−3.10, −2.82)** | ||||

| Age | 0.99 (0.99, 0.99)** | 0.09 (0.08, 0.10)** | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/Living with partner | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Never married | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97)** | −1.34 (−1.50, −1.17)** | ||||

| Widowed/Divorced/Sepa rated | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 0.16 (−0.1, 0.34) | ||||

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| Current drinker | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Former drinker | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 1.10 (0.88, 1.31)** | ||||

| Lifetime abstainer | 0.86 (0.81, 0.91)** | −0.13 (−0.38, 0.11) | ||||

| Educational level | ||||||

| 0–11 years/12 years without diploma | 1 | 1 | ||||

| HS diploma/GED or equivalent | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10)* | −0.87 (−1.07, −0.67)** | ||||

| Some college/AA degree | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36)** | −2.12 (−2.32, −1.91)** | ||||

| BA degree and higher | 1.29 (1.22, 1.36)** | −4.86 (−5.11, −4.62)** | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.33 (1.27, 1.40)** | −5.36 (−5.54, −5.19)** | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22)** | −7.82 (−8.03, −7.61)** | ||||

| Non-Hispanic all other race groups | 1.16 (1.06, 1.26)** | −4.38 (−4.74, −4.03)** | ||||

| Constant | 0.81 (0.80, 0.83) | 0.74 (0.72, 0.75) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17)* | 14.13 (14.04, 14.23)** | 13.60 (13.50, 13.70)** | 17.31 (16.93, 17.69)** |

| Model fit R2, p-value | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.17 | |||

| Model fit p-value | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

year centered on 2006 (−9 to 9), and divided by 10

HS, High School; GED, General Educational Development (High School Equivalency); AA, Associate; BA, Bachelor

CPD declined over time for all K6 categories of smokers (p<0.01; Figure 1C and Table 2). Cigarette consumption was higher among smokers with serious distress (19.6 CPD in 1997, falling to 14.5 CPD in 2015) than among those without distress (16.3 CPD in 1997, falling to 11.2 in 2015). In the fully adjusted model, smokers with moderate distress smoked 1.37 (95% CI=1.19, 1.54), and smokers with serious distress 3.69 (95% CI=3.36, 4.03) more CPD than those without distress (p<0.01; Table 3). People with moderate psychological distress reduced CPD faster than people without psychological distress (p<0.05) whereas people with serious distress reduced consumption at a similar rate as people without distress based on interaction terms in Appendix Table 3. In a sensitivity analysis that treated K6 level as a continuous variable, a significant effect was found (p=0.006) for the interaction of K6 level X time (not shown).

Table 2.

Consumption Cigarettes/Day (Coefficients and 95% CIs From Linear Regression)

| Covariates and model fit | No psychological distress | Moderate psychological distress | Serious psychological distress | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Time (per 10 years) a | −2.88 (−3.06, −2.71)** | −2.77 (−2.92, −2.62)** | −3.28 (− 3.58, −2.97)** | −3.16 (−3.43, −2.88)** | −3.25 (− 3.87, −2.63)** | −3.35 (−3.94, −2.75)** |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | −3.00 (−3.17, −2.84)** | −2.64 (−2.95, −2.34)** | −3.57 (−4.18, −2.96)** | |||

| Age | 0.09 (0.08, 0.10)** | 0.09 (0.08, 0.10)** | 0.08 (0.05, 0.10)** | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/Living with partner | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Never married | −1.34 (−1.53, −1.15)** | −1.41 (−1.76, −1.05)** | −1.00 (−1.89, −0.11)* | |||

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 0.23 (0.04, 0.42)* | 0.19 (−0.21, −0.59) | −0.46 (−1.16, 0.25) | |||

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| Current drinker | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Former drinker | 1.25 (1.00, 1.49)** | 0.95 (0.52, 1.37)** | 0.45 (−0.30, 1.21) | |||

| Lifetime abstainer | −0.10 (−0.38, 0.17) | −0.35 (−0.91, 0.21) | 0.19 (−0.90, 1.28) | |||

| Educational level | ||||||

| 0–11 years/12 years without diploma | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| HS diploma/GED or equivalent | −0.83 (−1.08, −0.59)** | −0.81 (−1.21, −0.41)** | −1.48 (−2.35, −0.62)** | |||

| Some college/AA degree | −2.22 (−2.47, −1.97)** | −1.87 (−2.28, −1.45)** | −1.67 (−2.58, −0.76)** | |||

| BA degree and higher | −4.89 (−5.18, −4.61)** | −4.70 (−5.25, −4.15)** | −4.70 (−6.05, −3.35)** | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | −5.27 (−5.47, −5.07)** | −5.36 (−5.73, −4.99)** | −6.56 (−7.39, −5.73)** | |||

| Hispanic | −7.84 (−8.08, −7.61)** | −7.58 (−8.00, −7.16)** | −8.36 (−9.25, −7.47)** | |||

| Non-Hispanic all other race groups | −4.48 (−4.87, −4.09)** | −3.88 (−4.67, −3.09)** | −4.99 (−7.37, −2.60)** | |||

| Constant | 13.60 (13.50, 13.70)** | 17.37 (16.93, 17.82)** | 14.77 (14.60, 14.94)** | 18.00 (17.23, 18.77)** | 17.50 (17.14, 17.85)** | 23.08 (21.47, 24.69)** |

| Model fit R2 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| Model fit p-value | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

Year centered on 2006 (−9 to 9), and divided by 10.

HS, High School; GED, General Educational Development (High School Equivalency); AA, Associate; BA, Bachelor

The changes with time were essentially the same in the adjusted and unadjusted models for both outcomes, indicating that the demographic factors were not confounding variables.

DISCUSSION

The analyses showed that, consistent with other literature,19 over time smoking prevalence among those with psychological distress declined, albeit the decline being slower than in people without psychological distress. Although smoking more heavily than people without psychological distress, like people without psychological distress and the general population,6–8 smokers with psychological distress are softening over time. Between 1997 and 2015 smokers with both moderate and with serious psychological distress showed significant increases in quit attempts and a significant decreases in the average number of cigarettes smoked. These results reject the hypothesis of hardening over time and, instead, support softening among smokers with psychological distress.

The finding that the proportion of those with at least one quit attempt in the past 12 months is higher among those with psychological distress compared with those without might reflect the fact that although this subgroup of smokers is motivated and willing to quit, they may have a harder time quitting successfully. Cooper and colleagues20 found using a population-based sample that smokers with depressive symptoms make more quit attempts, and might have a higher motivation to quit, but are also more likely to relapse within 30 days. Smith et al.21 similarly found a lower likelihood of long-term cessation success among those with mental illness compared with those without, with cessation rates varying by different diagnoses.

Mental health providers have often been reluctant to treat tobacco dependence in mental health and addiction treatment settings because of the incorrect assumption that treating nicotine addiction complicates treating other substance abuse or mental health issues.22 Prochaska and others23–26 showed that prioritizing smoking cessation is consistent with good clinical practice among depressed smokers. Likewise, smoking cessation often improves clinical outcomes in people in substance abuse treatment and recovery and can even enhance long-term sobriety.27–29 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Taylor et al.30 showed that both in the general population and in a clinical setting quitting smoking is associated with improved positive mood and quality of life,31 which should reassure smokers with psychological distress as well as their healthcare providers to make quitting one of their priorities.

A major strength of the analyses is the long period of time under analysis. Another strength is the large sample size of this national population representative sample that allowed to not just differentiate between those with and without serious psychological distress (K–6 scores of 0–12 vs 13–24), but to also make a distinction between those with moderate and serious distress. These two subgroups of smokers vary in their levels of smoking prevalence between each other and when compared with those without distress (Figure 1). Although quit attempts do not vary over time between the three groups, for CPD there was a significant difference in time trends between those without and with moderate distress, and a marginal one between those without and with serious distress (Appendix Table 3), a result confirmed in a sensitivity analysis that treated K6 level as a continuous variable and found a significant effect for the interaction of K6 level X time.

Limitations

A potential limitation of this study is that the NHIS is a survey of the non-institutionalized population, so does not include institutionalized smokers who may have more severe diagnoses of depression and mental distress, with the result that these people are excluded from the analyses. Second, whereas the K6 scale is a validated instrument, it is a self-assessment of mental distress symptoms, which might be less reliable than a physician-verified diagnosis of depression. The R2 values for the unadjusted models for CPD were, while highly significant, were low. Third, because quit attempts were measured in the past 12 months, whereas psychological distress questions referred to the past 30 days, it is not possible to assess whether these two conditions coincided directly.

CONCLUSIONS

Even smokers with serious psychological distress are willing to quit and to reduce consumption over time, just like the population of those without distress, albeit from higher baseline prevalence and consumption rates. With appropriate tailored interventions and quitting help these heavier smokers can successfully quit smoking. To achieve this goal in mental health settings more attention has to be paid to quitting smoking. To improve health outcomes and increase health equity, tobacco control policies should continue moving all subgroups of smokers down these softening curves.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nadra E. Lisha for her statistical advice.

Dr. Kulik was supported by the University of California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program Grant 25FT-0004. Dr. Glantz’ work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01DA043950. The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

MCK collected the data, computed the statistics, and drafted the manuscript. SAG advised on data analysis and revised the manuscript.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Warner KE, Burns DM. Hardening and the hard-core smoker: concepts, evidence, and implications. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):37–48. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000060428. https://doi.org/10.1080/1462220021000060428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter KM. Hardcore smoking does not necessarily indicate hardening. Addiction. 2014;109(4):681. doi: 10.1111/add.12453. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JE, McDonald PW, Selby P. Softening up on the hardening hypothesis. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):265–266. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050381. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docherty G, McNeill A. The hardening hypothesis: does it matter? Tob Control. 2012;21(2):267–268. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050382. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa ML, Cohen JE, Chaiton MO, Ip D, McDonald P, Ferrence R. “Hardcore” definitions and their application to a population-based sample of smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(8):860–864. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq103. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntq103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulik MC, Glantz SA. The smoking population in the USA and EU is softening not hardening. Tob Control. 2016;25(4):470–475. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052329. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez E, Lugo A, Clancy L, Matsuo K, La Vecchia C, Gallus S. Smoking dependence in 18 European countries: Hard to maintain the hardening hypothesis. Prev Med. 2015;81:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards R, Tu D, Newcombe R, Holland K, Walton D. Achieving the tobacco endgame: evidence on the hardening hypothesis from repeated cross-sectional studies in New Zealand 2008–2014. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):399–405. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052860. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, SAMHS. The CBHSQ Report. [Accessed June 2016];Smoking rate among adults with serious psychological distress remains high. 2013 Jul 18; www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/spot120-smokingspd_/spot120-smokingSPD.pdf.

- 11.Seidman DF, Covey LS, editors. Helping the Hard-Core Smoker - A Clinician’s Guide. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahway, NJ: London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darville A, Hahn EJ. Hardcore smokers: what do we know? Addict Behav. 2014;39(12):1706–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. [Accessed June 2016];National Health Interview Survey. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/

- 16.Prochaska JJ, Sung HY, Max W, Shi Y, Ong M. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(2):88–97. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1349. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1995–2004. Vital Health Stat. 2000;2(130):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons VL, Moriarity C, Jonas K, Moore TF, Davis KE, Tompkins L. Design and estimation for the national health interview survey, 2006–2015. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2(165):1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311(2):172–182. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284985. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.284985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper J, Borland R, McKee SA, Yong HH, Dugue PA. Depression motivates quit attempts but predicts relapse: differential findings for gender from the International Tobacco Control Study. Addiction. 2016;111(8):1438–1447. doi: 10.1111/add.13290. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e147–153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051466. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prochaska JJ. Smoking and mental illness--breaking the link. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):196–198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105248. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1105248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prochaska JJ. Failure to treat tobacco use in mental health and addiction treatment settings: a form of harm reduction? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110(3):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochaska JJ, Hall SM, Tsoh JY, et al. Treating tobacco dependence in clinically depressed smokers: effect of smoking cessation on mental health functioning. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):446–448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101147. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.101147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, et al. Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1808–1814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080382. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prochaska JJ, Schane R, Leek D, Hall SE, Hall SM. Investigation into the cause of death of a 56-year-old man with serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):453–456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091455. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKelvey K, Thrul J, Ramo D. Impact of quitting smoking and smoking cessation treatment on substance use outcomes: An updated and narrative review. Addict Behav. 2017;65:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prochaska JJ, Delucchi K, Hall SM. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions with individuals in substance abuse treatment or recovery. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1144–1156. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thurgood SL, McNeill A, Clark-Carter D, Brose LS. A Systematic Review of Smoking Cessation Interventions for Adults in Substance Abuse Treatment or Recovery. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):993–1001. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prochaska JJ. Quitting smoking is associated with long term improvements in mood. BMJ. 2014;348:g1562. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1562. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.