Abstract

New techniques for single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) at high throughput are leading to profound new discoveries in biology. The ability to generate vast amounts of transcriptomic data at cellular resolution represents a transformative advance allowing the identification of novel cell types, states and dynamics. In this review, we summarize the development of scRNA-seq methodologies and highlight their advantages and drawbacks. We discuss available software tools for analyzing scRNA-Seq data and summarize current computational challenges. Finally, we outline ways in which this powerful technology might be applied to discovery research in kidney development and disease.

Introduction

Understanding kidney cell function and defining the gene regulatory mechanisms that underlie cell behavior represent questions of fundamental importance in nephrology. The kidney is a highly complex tissue with a broad range of specialized cell types organized into functionally distinct compartments. Traditional approaches for characterization of kidney cell types have relied on microscopy or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). These offer high spatial resolution but rely on a limited number of markers, precluding comprehensive characterization of kidney cell types and states.

A single genome gives rise to the remarkable diversity of cell types through differences in gene expression. For this reason, transcriptional profiling is a powerful approach to categorize heterogeneous cell types and states. Over the last two decades, knowledge regarding the transcriptional landscape in kidney has come largely from whole organ profiling using either microarray1 or next generation RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq).2, 3 These studies have been highly informative, but they are fundamentally limited to describing a transcriptional average across a cell population which may hide or skew signals of interest. Alternative approaches have attempted to achieve finer separation of kidney compartments to address the issue of mixed cell type signatures. For example, Lee et al microdissected 14 tubule segments and analyzed the transcriptome of each individual segment.4 But this approach does not reveal individual cell states, and cannot distinguish separate cell types within a particular segment such as principal and intercalated cells. Laser capture microdissection can achieve compartment-specific transcriptional profiles, but like microdissection, it cannot resolve interstitial or glomerular cell types.5

Other more recent advances have improved researchers' ability to perform cell typespecific mRNA profiling. RNA-seq of FACS sorted cells6 and translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP)7-9 have provided great insight into the molecular signatures and gene regulatory networks for specific cell types in kidney development, homeostasis and disease. However, these techniques require advance knowledge of cell markers to define cell types. In addition, the profiling data obtained from those techniques still represent the averaged expression of a group of cells. Important features like inter-cell heterogeneity and cell subtypes may be masked in these population-averaged measurements.

Single cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq)10, 11 combines comprehensive genomics with single-cell resolution, and represents a fundamentally new method for the comprehensive measurement of cell state. It allows the characterization of cell identity independent of predefined markers or assumptions regarding cell hierarchies. scRNA-seq also enables the bioinformatic reconstruction of dynamic cellular process such as development, differentiation and disease progression, something not possible with bulk profiling techniques. In this review, we will discuss the development of scRNA-seq techniques and summarize potential applications in kidney disease investigation.

Development of scRNA-seq Protocols

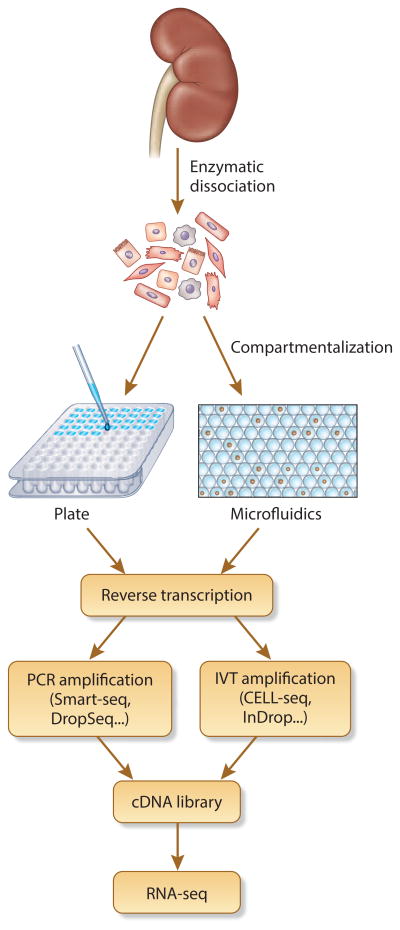

All scRNA-seq techniques share several common steps: single cell isolation, cell lysis and RNA capture, reverse transcription, amplification, library generation and next generation sequencing (Figure 1). Since the first scRNA-seq paper published in 2009 by Tang et al,12 numerous improvements have been made. One challenge concerns how to prepare cDNA libraries from the minute amount of RNA in a single cell. A mammalian cell contains about 10 picograms of total RNA. Only 10-20% of this is reverse transcribed regardless of the scRNA-seq protocol and as a consequence all protocols utilize an RNA amplification step. The original protocol developed by Tang et al12 used PCR to amplify libraries from single cells, but it required multiple PCR tubes and a gel purification step, leading to substantial loss of genetic material. Later amplification methods took advantage of PCR amplification but omitted gel purification, including STRT-seq,13 Smart-seq,14 Smart-seq2,15 SC3-seq,16 DropSeq,17 and SeqWell (Table 1).18 An alternative approach to amplify libraries, in vitro transcription (IVT), was developed and incorporated into CELL-Seq,19 CELL-Seq2,20 MARS-Seq21 and InDrops.22 (Table 1) The strengths and drawbacks of these protocols have been reviewed in detail by Kolodziejczyk et al.23

Figure 1. scRNA-seq experimental workflow.

All scRNA-seq protocols share the following common steps: 1) Enzymatic dissociation of the sample into a single cell suspension. 2) Compartmentalization of single cells into individual chamber (well or oil droplet). 3) Reverse transcription. 4) Library amplification via PCR or IVT depending on the protocol selected. 5) Library fragmentation/tagmentation. 6) RNA-seq.

Table 1. Comparison of plate and microfluidic-based scRNA-seq.

| Method | Plate-based scRNA-seq | Microfluidic-scRNA-seq | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRT-seq (V1/V2) | SMART-seq (V1/V2) | CELL-seq (V1/V2) | MARS-seq | DropSeq | InDrops | 10× Chromium | |

| Year | 2012/2014 | 2012/2013 | 2012/2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2015 | 2016 |

| UMI | No/Yes | No/No | No/Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| RNA Spike-in | No/Yes | No/No | Yes/Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Commercial | Fluidigm | Fluidigm | Fluidigm | NA | NA | 1CellBio | 10× Genomics |

| Full-length coverage | No/No | Yes/Yes | No/No | No | No | No | No |

| 2nd strand synthesis | Template switching | Template switching | RNAseH +DNA Pol | RNAseH +DNA Pol | Template switching | RNAseH +DNA Pol | Template switching |

| Library Amplification | PCR | PCR | IVT | IVT | PCR | IVT | PCR |

| Cell barcode | Yes/Yes | No/Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Library cost ($ per cell) | ∼2 | ∼3 (in-house) | ∼9 | ∼1.3 | ∼0.1 | ∼0.1 | |

| Dropout rate* | NA | 0.45/0.26 | NA/0.45 | 0.74 | 0.72 | NA | NA |

| Profiling capacity (#cells) | <100 | 100-500 | 100-500 | 1,000-5,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | ∼80,000 |

Based on Ziegenhain et al29

The introduction of unique molecular identifiers (UMI)24 represents a critical advance because they correct for amplification artifacts that arise during library preparation. UMIs are random sequences of bases (or barcodes) that label each transcript before library amplification. After sequencing, reads that have different barcodes represent different original molecules, but reads that have the same barcode resulted from PCR duplication of one original molecule. Artifactual PCR duplicates can therefore be tracked and eliminated during downstream analysis. This technology was first integrated in STRTseq,24 and later inherited by CELL-Seq2,20 DropSeq,17 InDrops22 and SeqWell (Table 1).18

UMIs correct for amplification bias but they do not compensate for biological variation resulting from disparate RNA amounts across cells. This requires a “spike-in” of a known amount of synthetic RNA into the libraries (e.g. External RNA Controls Consortium or ERCC spike-ins),25 and this technique has been widely employed by many newer single cell techniques. However, droplet based scRNA-seq techniques cannot easily accommodate spiked-in RNA due to the nature of the microfluidic design. Alternative data quality control measures must be performed on scRNA-seq techniques without spike-ins. For example, cell-specific biases can be normalized by cell-based size factor26 and cell-cell variations including cell mapping rate, number of detected transcripts and mitochondrial gene fraction can be controlled for during downstream analysis.

Recent technological advances in robotics, microfluidics and reverse emulsion droplets have dramatically increased assay throughput from hundreds of cells to tens of thousands of cells per experiment. This increased throughput has increased the power of the approach but also increased complexity of experimental design and interpretation. We illustrate some of these issues in the next section by comparing plate-based and microfluidic-based scRNASeq.

Plate/tube-based scRNA-Seq

Constructing a cDNA library from a single cell is fundamentally similar to creating a cDNA library from a large group of cells except for the scale. The main difference is cell compartmentalization. The original method developed by Tang et al12, 27 used manual cell transfer into an individual PCR tube making it difficult to scale up to hundreds of cells. Plate-based scRNA-seq such as STRT-seq significantly improved efficiency by transferring cells into a 96-well plate through a custom-built semi-automated cell picker.13 STRT-seq also introduced barcoding to cDNA libraries, allowing pooling and multiplexed analysis of all 96 samples. This important advance was achieved using a “template switching” technique. Reverse transcriptases derived from Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus possess intrinsic terminal transferase activity resulting in the addition of several cytosines at the 3′ terminus of the RNA molecule. When an oligonucleotide with complementary guanosine bases is present, transient annealing may occur to the protruding cytosines, and the reverse transcriptase can switch templates and incorporate new sequences (encoded by the oligonucleotide) at both ends of the cDNA molecule. By encoding different barcodes on the template switching oligonucleotide in each well of the 96-well plate, libraries can be combined, pooled, and separated bioinformatically after sequencing.

Other improvements followed. SMART-seq uses a similar template-switching strategy as STRT-seq but has enhanced ability to capture full-length transcripts.14 SMART-seq2 further improves cDNA yield and optimized reverse transcription, template switching and PCR amplification.15 To reduce bias introduced by non-linear PCR amplification, CELL-Seq was developed featuring the use of in vitro-transcription (IVT) and multiplexing to increase efficiency and accuracy.19 CELL-Seq2 further enhanced the sensitivity and improved the quality of the data with the introduction of UMIs.20 All of these approaches require multiple steps and remain relatively laborious.

Plate and tube based scRNA-seq are costly due to the relatively large volumes required in a microliter well/tube – about $5 - $10/cell for library creation. Modifications have been made to reduce the cost while preserving the capacity of scRNA-seq. A good example is to adapt STRT-seq, SMART-seq and CELL-Seq to integrated fluidic circuits in the Fluidigm C1 system.20, 24, 28 The Fluidigm C1 system can capture up to 800 single cells in nanoliter chambers, reducing cost. The autoprep system in Fluidigm C1 also allows user to simply load the cell suspension onto the chip without relying on FACS sorting, reducing labor. However, the cell capture chamber is a fixed size, which may bias against capture of cells with different sizes. Moreover, the cost of the Fluidigm C1 system remains high - $3.5/cell.

On the other hand, plate-based scRNA-seq provides unparalled transcript detection sensitivity. One recent study concluded that plate-based scRNA-seq can detect two-fold more genes per cell than microfluidic based scRNA-seq, even though the total number of detected genes across many cells is comparable across techniques.29 Moreover, this study also reported that full-length scRNA-seq methods (e.g. SMART-seq or SMART-seq2) had higher sensitivity (e.g. more genes being detected and higher fraction of transcripts being turned into sequencible molecules) than other plate based methods.29

Microfluidic based scRNA-Seq

Very recently microfluidic droplet technologies were reported that allow co-encapsulation of a cell, barcoded DNA oligonucleotides and cell lysis buffer within a tiny droplet of about 2 nanoliters,17, 22 which dramatically reduces the amount of RT reaction buffer used while increasing throughput. Droplets are one thousand times smaller than volumes in a traditional plate/tube based scRNA-seq assay and so these approaches are highly scalable (the number of “chambers” is unlimited) allowing for parallel processing of thousands of cells within an hour.

a. DropSeq

DropSeq was developed by the McCarroll lab and reported in 2015.17 The technique relies on two design concepts: chip microfluidics and barcoded beads. The microfluidic chip allows co-flow of oil, cells, and barcoded beads to generate millions of nanoliter-size droplets within an hour. Cells and barcoded beads are randomly co-encapsulated in the droplets, resulting in thousands of droplets containing one cell and one bead.17 The oligonucleotide sequences carried on DropSeq beads have four functions: primer handle for PCR amplification, cell barcodes to tag millions of individual cells, a UMI for accurate transcript counts, and oligo-dT to capture mRNA released from each cell.17 Library construction in DropSeq consists of template-switching RT followed by PCR amplification. Due to the inexpensive and high throughput nature of DropSeq, it has rapidly spread into hundreds of labs worldwide as a core scRNA-seq technique. There are publicly available resources, videos and discussion groups (Table 2). To date, DropSeq has been successfully applied to study the cell diversity in retina,17 retina bipolar cells,30 and brain organoids to list just a few examples.31

Table 2. Online resources for scRNA-seq.

| Tools | Functions | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Raw sequencing data processing tools | ||

| FastQC | Raw data QC | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ |

| RSeQC | RNA-seq QC Package | http://dldcc-web.brc.bcm.edu/lilab/liguow/CGI/rseac/build/html/ |

| Trimmomatic | Read trimming | http://www.usadellab.org/cms/index.php?page=trimmomatic |

| Picard | Command line tools for RNA-seq files | https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ |

| STAR | Ultrafast read mapper | Tools: https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR Forum: https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/rna-star |

| Bowtie | Memory-efficient mapper | Bowtie: http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml Bowtie2: http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| HI SAT | Fast and sensitive mapper | HISAT: http://www.ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat/index.shtml HISAT2: http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/index.shtml |

| scRNA data normalization and dimensionality reduction tools | ||

| MAST | Model-based analysis of scRNA-seq data | https://github.com/RGLab/MAST |

| SCDE | Bayesian approach to model scRNA-seq data | https://github.com/hms-dbmi/scde |

| ZIFA | Dimensionality reduction for scRNAseq data | https://github.com/epierson9/ZIFA |

| tSNE | Non-linear dimensionality reduction approach | http://lvdmaaten.github.io/tsne/ |

| viSNE | Dimensionality reduction tool | http://www.c2b2.columbia.edu/danapeerlab/html/cyt.html |

| scRNA-seq clustering and pseudotemporal ordering tools | ||

| PhenoGraph | Clustering method designed scRNA-seq | https://github.com/jacoblevine/PhenoGraph |

| SNN-cliq | Graph-based clustering approaches | http://bioinfo.uncc.edu/SNNCliq/ |

| Monocle | Toolkit for pseudotemporal ordering of single cells | http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/monocle-release/ |

| Wanderlust | Graph-based trajectory detection algorithm | http://www.c2b2.columbia.edu/danapeerlab/html/wanderlust.html |

| Wishbone | Tool for analyzing bifurcating branches | http://www.c2b2.columbia.edu/danapeerlab/html/wishbone.html |

| Microfluidic-based scRNA-seq resources | ||

| DropSeq | DropSeq protocol and computational tools | http://mccarrolllab.com/dropseq/ |

| DropSeq group | Scientific community for DropSeq troubleshooting | https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/dropseq |

| DropSeq video | Youtube channel providing Drop-seq tutorial | https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRptwggZzFyM51R5iAI-07Q |

| InDrops resources | InDrops computational pipeline | https://github.com/indrops/indrops |

| Seurat | QC and clustering for DropSeq/inDrops data | http://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

While DropSeq has exploded onto the scientific scene, there are drawbacks to this approach for single cell studies. It has a low cell capture efficiency, capturing only about 5% of input cells, making it unsuitable for analysis of precious clinical samples where the cell number is limited (e.g. kidney biopsy). Another drawback of DropSeq concerns the low read mapping rate. According to the DropSeq community, only 60%-80% of the high quality raw reads will finally mapped to genome, of which more than 30% mapped reads are allocated to empty or low quality beads depending on the quality of single cells input, which will be eventually removed from data analysis. Thus sequencing costs are considerable. Finally, like other microfluidic techniques, DropSeq can only detect the top 20% most abundant transcripts. Since many signaling molecules and transcription factors are expressed at low levels, DropSeq will not be able to detect many of them.

b. InDrops

InDrops is another microfluidic based scRNA-seq established by Allon Klein et al22 and published at the same time as DropSeq. Its unique advantage is that it can barcode 60%-90% of the total input cells. That is achieved by use of a deformable hydrogel which contains the barcodes, allowing very dense packing and synchronization of hydrogel release with droplet formation. InDrops is therefore a good choice for high throughput scRNA-seq analysis of small samples. Another feature of InDrops is that it adapts the IVT amplification method from CELL-Seq for library construction, minimizing amplification artifact.22 InDrops has also been applied across species and conditions. For example, Baron et al has successfully implemented InDrops to compare the single cell transcriptome between mouse and human pancreas.32 Briggs et al applied inDrops to compare motor neurons generated by two differentiation protocols and revealed that mature cell state can be reached via multiple differentiation paths.33

Limitations of the InDrops approach include higher technical skill required to pack the hydrogels in order to ensure regular release during the microfluidic run, and more laborious library construction. The incompatibility of Illumina's PhiX standard library spike-ins during sequencing also increases the risks of sequencing failure particularly for those InDrops libraries with extremely low diversity. Finally, the InDrops microfluidic channel design is proprietary and must be purchased from 1CellBio, a spinoff company that has licensed the InDrops technology. This is in contrast to DropSeq, where the microfluidic channel design is public and can be easily and cheaply fabricated by any laboratory.

A major advantage of both DropSeq and InDrops is the very low cost per cell. According to Macosko et al, reagent cost for DropSeq can be as low as 6 cents per cell, >100-fold lower than the plate-based scRNA-seq. The cost for inDrops was also reported to be only 4 cents per cell. Cost savings is achieved because the RT reaction occurs in tiny nanoliter droplets, reducing reagent requirements per cell. Costs are further reduced through parallel processing of thousands of cells during cDNA library preparation because of the barcoding approach used by both DropSeq and inDrops.

c. Commercial microfluidic scRNA-seq

10× genomics sells a Chromium system machine using microfluidic encapsulation that can barcode 100 – 80,000 cells in 10 minutes with 65% cell capture rate, at $0.15 – $1 per cell. This platform is rapidly gaining traction in the scRNA-seq community because of its relative ease of use and its high cell capture rate. As a comparison, a DropSeq rig must be constructed from individual parts and mastering its operation generally takes about 6 months. The Chromium system also comes with a proprietary data analysis and visualization software package that greatly accelerates bioinformatic analysis for laboratories that are less familiar with coding. The power of this system was recently illustrated where a single experiment resulted in 68,000 single cell transcriptomes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells.34 When sequenced at a depth of 20,000 reads per cell, the authors could detect about 500 unique genes and 1300 transcripts per cell. Last year, Illumina announced their partnership with BioRad to bring a new high throughput scRNA platform. This system utilizes BioRad's droplet technology (ddSEQ™ Single-Cell Isolator system) and Illumina's Nextera library preparation system (SureCell WTA 3′ Library Prep Kit), aiming at separating and barcoding 10,000 individual cells at $1 per cell, in a matter of hours. Illumina+BioRad also provides analytical software and computing cluster space that can be a major asset for smaller labs that lack access to sufficient computing power.

Data analysis

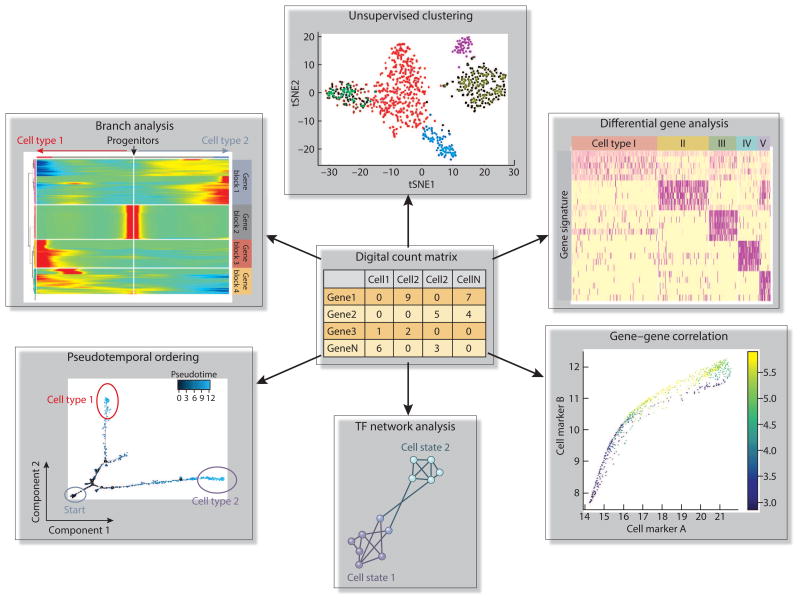

Bioinformatic analysis of scRNASeq experiments is computationally intensive. The initial steps are similar to bulk RNA-seq data with the major difference being that UMIs and cell barcodes must be processed. The final result is generation of a digital expression matrix, which consists of trimming the low-quality reads, mapping reads against the reference genome, assigning the mapped reads to cell barcodes, and quantifying the molecule counts for each gene in each cell. The resulting matrix represents an enormous dataset. Even a relatively simple DropSeq experiment might yield data for 5,000 cells, with 2,000 unique genes detected in each cell at specific expression levels. A simplified representation of the digital count matrix is shown in Figure 1.

For all scRNA-seq data, a key challenge is that gene expression counts only record a small fraction of the whole transcriptome in a cell so many counts are zero (“dropout”). High “dropout” rates introduce significant noise into the dataset posing challenges for proper interpretation. Currently, several models have been proposed to accommodate the abundance of zero values present in scRNA-seq data35, 36 and new normalization approaches are being developed to normalize zero-inflated data (Table 2).26 The challenge is more often to choose an appropriate approach that can effectively apply to researcher's own single cell dataset.

Cell type heterogeneity and diversity can be revealed through dimensionality reduction and unsupervised clustering methods (Table 2) to process high dimensional single cell data (e.g. if 10,000 genes are detected in a cell, there will be 10,000 dimensions for that cell). For low throughput single cell data principle component analysis was frequently used to separate important cell types but it fails to work if the data is not linearly related which is usually the case for most of the single cell datasets. t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) is a superior dimensionality reduction method (Table 2) that is thought to be more suitable for visualizing high throughput scRNA-seq data. The Pe'er lab further developed t-SNE machine learning algorithm and created viSNE which has been tested in their leukemia scRNA-seq dataset.37 More recently, ZIFA,38 a new dimensionality reduction approach, showed better performance on zero-inflated scRNAseq data. In addition to dimensionality reduction, unsupervised graph-based clustering methods have also been developed to classify the subpopulations and to identify the markers responsible for the difference across subpopulations (e.g. SNN-Cliq39 and PhenoGraph40). Often investigators need to test multiple clustering algorithms on the same dataset in order to determine which one yields the most meaningful results for that particular experiment.

The development of machine learning tools allows for pseudotemporal ordering of cells along a trajectory corresponding to a biological process such as differentiation. This can be accomplished by a number of bioinformatic packages such as Monocle,41 Wishbone,42 Wanderlust,43 and DPT.44 Construction of cell trajectories during a biological process with these tools can help to reveal markers for unrecognized intermediate state, gene regulation in cell fate decision, and cell subtype (Figure 2). Network analysis on gene pairs derived from those toolkits further aids in elucidating gene regulatory dynamics during development, differentiation and disease progression. This kind of analysis is particularly important for kidney research where a plethora of cellular events remain elusive or controversial.

Figure 2. scRNA-seq data analysis.

scRNA-seq data analysis begins with generation of a a digital expression matrix consisting of complete gene expression levels for each cell. This count matrix includes expression values for all the detected genes in each individual cell (e.g. gene names as the row names and cell names as the column names). Cells are usually grouped by unsupervised clustering approaches and visualized in a 2D tSNE graph. Cell types are classified by examining known marker gene expression in each cluster (as shown by the heatmap) through differential gene expression analysis between two clusters. Gene-gene correlation analysis helps to clarify the relationship between two marker genes within a cluster and the relationship of two marker genes from different clusters. Single cells can be ordered in a pseudotemporal trajectory that recapitulates a full biological process (e.g. development, differentiation and disease progression). Based on the trajectory, gene expression dynamics can be captured by branch analysis. Key regulators for the dynamic gene expression can also be revealed by regulatory network analysis on transcription factors (TF).

Applications of scRNA-Seq to Date

The ability to comprehensively define cell types and states may fundamentally change the way we conceptualize heterogeneous diseases such as AKI and CKD, providing better diagnostic tools, prognostic biomarkers and signaling pathways amenable to therapeutic targeting. A systematic molecular classification (Gene Expression Atlas) of kidney is one expressed goal of the NIDDK Kidney Precision Medicine Project45 and will inform our understanding of healthy kidney function and guide future therapeutics in the diseased state. These same approaches will likely guide improvements to kidney organoid differentiation from pluripotent stem cells. Very recent droplet based scRNASeq work in other tissues such as pancreas, retina and brain suggests that this analysis in kidney will almost certainly identify subpopulations, novel cell types and unappreciated heterogeneity.17, 22, 30-32

To date, a majority of published scRNA-seq techniques have been in the fields of neuroscience, stem cells and cancer. Several landmark papers have been published recently. Tirosh and colleagues performed scRNA-seq on 4,645 cells isolated from 19 patients with malignant melanoma.46 The analysis revealed subsets of malignant cells - one subset expressed high levels of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) whereas another expressed high levels of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL. These subgroups were negatively correlated with eachother and the AXL–high subgroups expressed other genes known to reflect resistance to targeted therapy – suggesting the presence of dormant, therapy-resistant cells within the heterogeneous tumor mass. Importantly, the AXL-high subgroup could not be detected through traditional bulk RNA-sequencing, reflecting the power of scRNA-seq to reveal otherwise hidden cell types and states. Finally, the AXL-high subgroup was enriched in patients that had received targeted therapy – suggesting that indeed this was a dormant, therapy resistant group of cancer cells. This type of analysis reveals one way that scRNA-seq can help predict treatment outcomes and guide therapy.

Baron and colleagues published a tour de force work examining the single cell transcriptome of mouse and human pancreas using InDrops.32 They generated transcriptomes from 12,000 human and mouse pancreas cells and were able to categorize them into 15 different cell types, reflecting all of the previously identified cell types including even rare epsilon-cells which constitute 0.1% of pancreatic cell mass. This systematic and unbiased classification of pancreatic cell types represents a highly detailed gene expression atlas that revealed novel ductal cell types as well as previously unrecognized heterogeneity among beta and ductal cells. Villani et al. profiled 2400 circulating dendritic cells and monocytes using a modified Smart-Seq2 protocol and very deep sequencing of 1-2 million reads per cell.47 Parenthetically, the sequencing costs alone for this experiment were in excess of $40,000. However this deep sequencing led to detection of more than 5,000 unique genes per cell, allowing fine distinctions betwee cell types. In fact, they defined three new, previously undescribed dendritic cell types and two novel monocyte cell types.

By contrast, implementation of scRNA-seq in kidney is still in early stages. Brunskill et al profiled 235 cells from E11.5, E12.5 kidneys and P4 renal vesicle to unravel the early molecular mechanisms of renal precursors patterning.48 They provided important evidence (at single cell resolution) to support that initial kidney organogenesis involves a multi-lineage priming process. These results were produced from Fluidigm C1 platform, and the implementation of SMART-seq library preparation strategy (full length RNA-seq) at a depth of 2.6 million reads/cell enabling them to investigate transcript variants as well as non-coding RNA.

Applying the same Fluidigm C1 platform on glomerular mesangial cells, Lu et al revealed that mesangial population is surprisingly heterogeneous (n=33).49 In the study, the authors also established a core marker list that marks all mesangial cells which may benefit lineage tracing studies for mesangial cells. Two groups have also attempted to implement scRNA-seq for the investigation of kidney diseases. Der et al isolated 361 renal biopsy cells from patients with lupus nephritis and profiled them on Fluidigm C1.50 With this dataset, they were able to correlate clinical parameters (proteinuria, IgG deposition, etc) with interferon responsive genes in tubular cells. However, because the healthy control group was missing in their experimental design, it has yet to be confirmed whether those genes are disease specific signature or just technical/biological artifact (e.g. responsive genes activated during kidney dissociation). The other application was reported by Kim et al also using Fluidigm C1 system.51 scRNA-seq profiling of 161 kidney cells from renal cell carcinoma patients enables them to develop a combinatorial regimen that targets two pathways in the cancer cells. Based on scRNAseq data, they proposed single-cell analysis-driven therapeutic strategy, which can be easily applied to other fields.

Although these scRNA-seq studies represent important first results of scRNASeq in nephrologic research, these studies also have limitations. First, the low throughput profiling using Fluidigm C1 system precludes the study of rare cell types. This can be reflected from Der et al 's dataset where two most important kidney cell types, podocyte and mesangial cells, were not identified.50 Even though reagent cost has been reduced due to the use of a nanoliter chamber in Fluidigm C1, per cell cost at $3.5 still prevents upscaling the number to thousands of cells.

Challenges to Overcome and Future Technological Development

There are several barriers to successful application of scRNA-seq to kidney. Kidney biopsies for research use are relatively difficult to obtain, and the sample size is small. Since DropSeq can only capture <5% of cells in a sample, it is poorly suited to generate a large single cell dataset from a small biopsy which may consist of only 50,000 – 100,000 cells total. The 10× Chromium system or InDrops platforms, with their >50% capture rates, are much better suited for analysis of human biopsies. The unpredictable availability of human kidney tissue and the absence of protocols for the storage of tissue followed by high throughput scRNA-seq compounds the challenges of working with human kidney. The recent development of in single nucleus RNA-seq is very encouraging in this regard. Two examples include Div-Seq52 and DroNc-seq53 which appear to promise many of the advantages of current microfluidic approaches with the added ability to process unfixed, frozen material. Another very recent advance is the ability to methanol fix and freeze dissociated cells, followed by rehydration and DropSeq analysis.54 Methanol fixation is compatible both with library preparation and next generation RNA-sequencing.55 This approach will greatly simplify the workflow for analyzing kidney biopsies and even enable the creation of biobanks of fixed kidney samples (the tissue must be dissociated before fixation however) that can be processed for scRNA-seq at a later date, for example after the pathologic diagnosis is known. Whether methanol fixed cells can be processed for scRNA-seq on platforms other than DropSeq is not known.

Finally, enzymatic dissociation of adult kidney is difficult. As enzymatic dissociation protocols usually compromise cell viability, and adult kidneys are relatively dense with matrix it can be difficult to generate a high quality single cell suspension that accurately reflects the transcriptional state of each cell before dissociation (Wu and Humphreys, unpublished observations). Proteolytic dissociation can induce transcriptional stress responses as well as RNA degradation. The possibility of selective cell loss during single cell dissociation may also lead to bias. For example, it may be relatively more difficult to dissociate mesangial cells out of the matrix in which they are embedded than it is to free podocytes whose attachments are limited to foot processes.

Conclusions

The emergence of scRNA-seq techniques are revolutionizing biology. This field is developing remarkably rapidly and we see great promise for its application to the study of kidney health and disease. Barriers for entry into this field are relatively low and we suggest that there are unique opportunities to apply scRNA-seq to better understand kidney development, homeostasis and disease.

Acknowledgments

Work in the Humphreys laboratory is supported by the NIH/NIDDK DK107374, DK103740 and DK104308 and and by an Established Investigator Award of the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Supavekin S, Zhang W, Kucherlapati R, et al. Differential gene expression following early renal ischemia/reperfusion. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1714–1724. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Q, Xiong Y, Huang XR, et al. Identification of Genes Associated with Smad3-dependent Renal Injury by RNA-seq-based Transcriptome Analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17901. doi: 10.1038/srep17901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakagawa S, Nishihara K, Miyata H, et al. Molecular Markers of Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis and Tubular Cell Damage in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JW, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Deep Sequencing in Microdissected Renal Tubules Identifies Nephron Segment-Specific Transcriptomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2669–2677. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014111067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMahon AP, Aronow BJ, Davidson DR, et al. GUDMAP: the genitourinary developmental molecular anatomy project. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:667–671. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boerries M, Grahammer F, Eiselein S, et al. Molecular fingerprinting of the podocyte reveals novel gene and protein regulatory networks. Kidney Int. 2013;83:1052–1064. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grgic I, Krautzberger AM, Hofmeister A, et al. Translational profiles of medullary myofibroblasts during kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1979–1990. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Krautzberger AM, Sui SH, et al. Cell-specific translational profiling in acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1242–1254. doi: 10.1172/JCI72126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grgic I, Hofmeister AF, Genovese G, et al. Discovery of new glomerular disease-relevant genes by translational profiling of podocytes in vivo. Kidney Int. 2014;86:1116–1129. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Navin NE. Advances and applications of single-cell sequencing technologies. Mol Cell. 2015;58:598–609. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gawad C, Koh W, Quake SR. Single-cell genome sequencing: current state of the science. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:175–188. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang F, Barbacioru C, Wang Y, et al. mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods. 2009;6:377–382. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam S, Kjallquist U, Moliner A, et al. Characterization of the single-cell transcriptional landscape by highly multiplex RNA-seq. Genome Res. 2011;21:1160–1167. doi: 10.1101/gr.110882.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramskold D, Luo S, Wang YC, et al. Full-length mRNA-Seq from single-cell levels of RNA and individual circulating tumor cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:777–782. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picelli S, Bjorklund AK, Faridani OR, et al. Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1096–1098. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura T, Yabuta Y, Okamoto I, et al. SC3-seq: a method for highly parallel and quantitative measurement of single-cell gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, et al. Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell. 2015;161:1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gierahn TM, Wadsworth MH, 2nd, Hughes TK, et al. Seq-Well: portable, low-cost RNA sequencing of single cells at high throughput. Nat Methods. 2017;14:395–398. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimshony T, Wagner F, Sher N, et al. CEL-Seq: single-cell RNA-Seq by multiplexed linear amplification. Cell Rep. 2012;2:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimshony T, Senderovich N, Avital G, et al. CEL-Seq2: sensitive highly-multiplexed single-cell RNA-Seq. Genome Biol. 2016;17:77. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaitin DA, Kenigsberg E, Keren-Shaul H, et al. Massively parallel single-cell RNA-seq for marker-free decomposition of tissues into cell types. Science. 2014;343:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.1247651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein AM, Mazutis L, Akartuna I, et al. Droplet barcoding for single-cell transcriptomics applied to embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2015;161:1187–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolodziejczyk AA, Kim JK, Svensson V, et al. The technology and biology of single-cell RNA sequencing. Mol Cell. 2015;58:610–620. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Islam S, Zeisel A, Joost S, et al. Quantitative single-cell RNA-seq with unique molecular identifiers. Nat Methods. 2014;11:163–166. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennecke P, Anders S, Kim JK, et al. Accounting for technical noise in single-cell RNA-seq experiments. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1093–1095. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lun AT, Bach K, Marioni JC. Pooling across cells to normalize single-cell RNA sequencing data with many zero counts. Genome Biol. 2016;17:75. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0947-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang F, Barbacioru C, Bao S, et al. Tracing the derivation of embryonic stem cells from the inner cell mass by single-cell RNA-Seq analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu AR, Neff NF, Kalisky T, et al. Quantitative assessment of single-cell RNA-sequencing methods. Nat Methods. 2014;11:41–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziegenhain C, Vieth B, Parekh S, et al. Comparative Analysis of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Methods. Mol Cell. 2017;65:631–643 e634. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shekhar K, Lapan SW, Whitney IE, et al. Comprehensive Classification of Retinal Bipolar Neurons by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Cell. 2016;166:1308–1323 e1330. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quadrato G, Nguyen T, Macosko EZ, et al. Cell diversity and network dynamics in photosensitive human brain organoids. Nature. 2017;545:48–53. doi: 10.1038/nature22047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron M, Veres A, Wolock SL, et al. A Single-Cell Transcriptomic Map of the Human and Mouse Pancreas Reveals Inter- and Intra-cell Population Structure. Cell Syst. 2016;3:346–360 e344. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Briggs JA, Lee S, Woolf CJ, et al. Mouse embryonic stem cells can differentiate via multiple paths to the same state. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.7554/eLife.26945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng GX, Terry JM, Belgrader P, et al. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nature communications. 2017;8:14049. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finak G, McDavid A, Yajima M, et al. MAST: a flexible statistical framework for assessing transcriptional changes and characterizing heterogeneity in single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2015;16:278. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0844-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kharchenko PV, Silberstein L, Scadden DT. Bayesian approach to single-cell differential expression analysis. Nat Methods. 2014;11:740–742. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amir el AD, Davis KL, Tadmor MD, et al. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierson E, Yau C. ZIFA: Dimensionality reduction for zero-inflated single-cell gene expression analysis. Genome Biol. 2015;16:241. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0805-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu C, Su Z. Identification of cell types from single-cell transcriptomes using a novel clustering method. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1974–1980. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levine JH, Simonds EF, Bendall SC, et al. Data-Driven Phenotypic Dissection of AML Reveals Progenitor-like Cells that Correlate with Prognosis. Cell. 2015;162:184–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trapnell C, Cacchiarelli D, Grimsby J, et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:381–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Setty M, Tadmor MD, Reich-Zeliger S, et al. Wishbone identifies bifurcating developmental trajectories from single-cell data. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:637–645. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bendall SC, Davis KL, Amir el AD, et al. Single-cell trajectory detection uncovers progression and regulatory coordination in human B cell development. Cell. 2014;157:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haghverdi L, Buttner M, Wolf FA, et al. Diffusion pseudotime robustly reconstructs lineage branching. Nat Methods. 2016;13:845–848. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The NIDDK Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP) [05/29/2017]; https://wwwniddknihgov/research-funding/research-programs/kidney-precision-medicine-project-kpmp.

- 46.Tirosh I, Izar B, Prakadan SM, et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352:189–196. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villani AC, Satija R, Reynolds G, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science. 2017;356 doi: 10.1126/science.aah4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunskill EW, Park JS, Chung E, et al. Single cell dissection of early kidney development: multilineage priming. Development. 2014;141:3093–3101. doi: 10.1242/dev.110601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu Y, Ye Y, Yang Q, et al. Single-cell RNA-sequence analysis of mouse glomerular mesangial cells uncovers mesangial cell essential genes. Kidney Int. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Der E, Ranabothu S, Suryawanshi H, et al. Single cell RNA sequencing to dissect the molecular heterogeneity in lupus nephritis. JCI Insight. 2017;2 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim KT, Lee HW, Lee HO, et al. Application of single-cell RNA sequencing in optimizing a combinatorial therapeutic strategy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Genome Biol. 2016;17:80. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0945-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Habib N, Li Y, Heidenreich M, et al. Div-Seq: Single-nucleus RNA-Seq reveals dynamics of rare adult newborn neurons. Science. 2016;353:925–928. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Habib N, Avraham-Davidi I, Burks T, et al. DroNc-Seq: Deciphering cell types in human archived brain tissues by massively-parallel single nucleus RNA-seq. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alles J, Karaiskos N, Praktiknjo SD, et al. Cell fixation and preservation for droplet-based single-cell transcriptomics. BMC Biol. 2017;15:44. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0383-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoeckius M, Maaskola J, Colombo T, et al. Large-scale sorting of C.elegans embryos reveals the dynamics of small RNA expression. Nat Methods. 2009;6:745–751. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]