Abstract

Introduction

This study assessed the prevalence of current high-intensity drinking (i.e., having ten or more drinks in a row in the past 2 weeks) among national samples of U.S. eighth and tenth grade students (at modal ages 14 and 16 years, respectively).

Methods

Data on high-intensity drinking were provided by 10,210 students participating in the nationally representative Monitoring the Future study in 2016, and analyzed in 2016–2017. Prevalence levels and interactions between grade and key covariates were estimated using procedures adjusting for the Monitoring the Future study’s complex sampling design.

Results

Approximately 2% of adolescents reported current high-intensity drinking, with significant differences by grade (1.2% of eighth graders; 3.1% of tenth graders) and gender (1.7% female; 2.3% male). High-intensity drinking was significantly higher among eighth and tenth grade students who reported any cigarette or marijuana use than among students who reported never using either substance.

Conclusions

A meaningful percentage of young adolescents in the U.S. engage in high-intensity drinking.

INTRODUCTION

High-intensity alcohol use, or the consumption of ten or more drinks on a single occasion,1 has been recognized as a high public health priority2 because of acute and long-term risks (e.g., injury, death, neurocognitive impairment, and alcohol use disorder). The prevalence of high-intensity drinking has been researched primarily in young adulthood (from individuals aged 19 to 30 years),3–5 when it peaks, and in older adolescence (among high school seniors).2,6 From 2005 to 2011, 10.5% of twelfth grade students in the U.S. reported consuming ten or more drinks in a row at least once in the past 2 weeks, with use among males significantly higher than among females.6 To date, no research has reported the prevalence of such high-intensity drinking behaviors among younger adolescents, or the extent to which they co-occur with other substance use. This study is the first to report the prevalence of current high-intensity drinking among young adolescents (in eighth and tenth grades) in the U.S. It also examines the extent to which young adolescent high-intensity drinking varies across key sociodemographic characteristics (grade, gender, race/ethnicity, and SES) and lifetime use of cigarettes and marijuana.

METHODS

Study Sample

The study uses data from the Monitoring the Future study7 collected during 2016 from nationally representative samples of eighth and tenth grade students (at modal ages 14 and 16 years) using self-completed, optically scanned questionnaires administered in classrooms by study personnel. A total of 32,873 students in 252 schools responded (response rates were 89.5% and 88.3% for eighth and tenth grades, respectively). Absenteeism was the primary reason for missing data; <1% of students refused participation. The study was approved by the University of Michigan IRB.

The question on high-intensity drinking (also called extreme binge drinking5–7) was included on a random one third of student surveys. A total of 10,938 students (5,887 eighth graders; 5,051 tenth graders) received the ten or more drinking item. The final sample size for analysis was 10,210 (93.3%) after data cleaning to remove cases with missing data for the ten or more drinking item (n=672), as well as cases with logically inconsistent answers; respondents who reported ten or more drinks in the past 2 weeks but never being drunk in the past 30 days (n=56) were excluded.

Measures

The current high-intensity drinking measure was: During the last two weeks, how many times (if any) have you had 10 or more drinks in a row? A drink was defined as follows: “a glass of wine, a bottle of beer, a wine cooler, a shot glass of liquor, a mixed drink, etc.” A dichotomy was coded indicating (1) any ten or more drinking vs (0) none. Respondents were also asked, What is your sex? with response options of male or female. Respondents self-reported race/ethnicity (coded for analysis as white vs non-white), parent education (coded as whether one or more parents graduated from college, used as a proxy for SES), and lifetime cigarette and marijuana use (both coded as any/none dichotomies).

Statistical Analysis

In 2016–2017, prevalence estimates were obtained using the SURVEYFREQ command in SAS, version 13.2, to account for the complex survey sampling design, with weights to adjust for differential probability of selection. For the sample overall, tests of significant differences in high-intensity drinking prevalence by each key covariate (gender, race/ethnicity, parental education, lifetime cigarette use, and lifetime marijuana use) were made using the Rao–Scott chi-square test. Possible interactions between grade and each listed covariate were examined individually via SURVEYLOGISTIC models by regressing high-intensity drinking on grade, one additional covariate, and an interaction of grade and the included covariate.

RESULTS

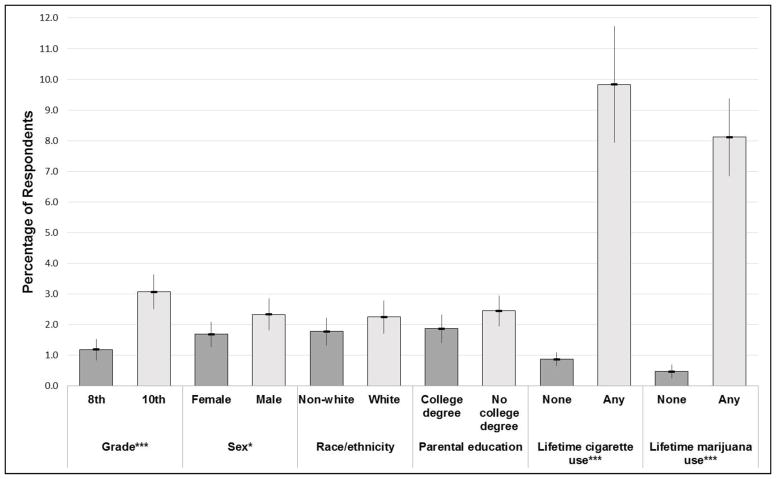

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all possible respondents as well as cases retained for analysis. Table 2 and Figure 1 present prevalence estimates for current high-intensity drinking overall and by covariates.

Table 1.

Comparative Descriptive Statistics for All Possible Respondents and Cases Retained for Analysis

| Characteristics | All possible respondents | Analytic sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| %a | (SE) | nb | % | (SE) | n | |

| Grade | 10,938 | 10,210 | ||||

| 8 | 53.8 | (3.79) | 53.5 | (3.81) | ||

| 10 | 46.2 | (3.79) | 46.5 | (3.81) | ||

| Gender | 10,387 | 9,829 | ||||

| Male | 49.2 | (0.62) | 49.0 | (0.63) | ||

| Female | 50.8 | (0.62) | 51.0 | (0.63) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 10,235 | 9,685 | ||||

| Non-white | 52.3 | (2.05) | 51.1 | (2.00) | ||

| White | 47.7 | (2.05) | 48.9 | (2.00) | ||

| Parental education | 9,693 | 9,195 | ||||

| No college education | 41.5 | (1.55) | 40.8 | (1.56) | ||

| College education | 58.5 | (1.55) | 59.2 | (1.56) | ||

| Lifetime cigarette use | 10,482 | 9,904 | ||||

| None | 87.0 | (0.61) | 87.7 | (0.58) | ||

| Any | 13.0 | (0.61) | 12.3 | (0.58) | ||

| Lifetime marijuana use | 10,532 | 10,037 | ||||

| None | 79.3 | (0.93) | 80.2 | (0.93) | ||

| Any | 20.7 | (0.93) | 19.8 | (0.93) | ||

Weighted percentage of respondents.

Unweighted n.

Table 2.

Prevalence of High-intensity Drinking Among Eighth and Tenth Grade Students in the U.S., 2016

| Characteristics | N | n | Prevalence | p-valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| (overall)a | (yes)b | %c | (95% CI) | ||

| Full sample | 10,210 | 231 | 2.1 | (1.7, 2.4) | |

| Grade | <0.001 | ||||

| 8 | 5,460 | 72 | 1.2 | (0.8, 1.5) | |

| 10 | 4,750 | 159 | 3.1 | (2.5, 3.6) | |

| Gender | 0.031 | ||||

| Male | 4,827 | 124 | 2.3 | (1.8, 2.9) | |

| Female | 5,002 | 94 | 1.7 | (1.3, 2.1) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.163 | ||||

| Non-white | 4,967 | 93 | 1.8 | (1.3, 2.2) | |

| White | 4,718 | 123 | 2.3 | (1.7, 2.8) | |

| Parental education | 0.072 | ||||

| No college education | 3,737 | 106 | 2.4 | (1.9, 2.9) | |

| College education | 5,458 | 109 | 1.9 | (1.4, 2.3) | |

| Lifetime cigarette use | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 8,675 | 89 | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.1) | |

| Any | 1,229 | 132 | 9.8 | (7.9, 11.7) | |

| Lifetime marijuana use | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 7,978 | 28 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | |

| Any | 2,059 | 190 | 8.1 | (6.9, 9.4) | |

Notes: High-intensity drinking is consumption of ten or more drinks on a single occasion in the past 2 weeks. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Overall unweighted n of respondents.

Unweighted n of respondents reporting engaging in ten or more drinking.

Weighted percentage of respondents reporting engaging in ten or more drinking.

P-value of Rao-Scott chi-square test of differences by noted comparison groups.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of high-intensity drinking among eighth and tenth grade students in the U.S., 2016.

Notes: High-intensity drinking is consumption of ten or more drinks in a single occasion in the past 2 weeks. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001 (Significance of Rao-Scott chi-square tests for differences in high-intensity drinking prevalence by noted characteristic).

Overall, 2.1% of eighth and tenth grade students combined reported high-intensity drinking in the past 2 weeks (Table 2). Prevalence was significantly higher for tenth grade students than eighth grade students (3.1% vs 1.2%, p<0.001). Males reported significantly higher prevalence than females (2.3% vs 1.7%, p<0.05). Prevalence also was significantly higher for lifetime cigarette users versus non-users (9.8% vs 0.9%, p<0.001) and for lifetime marijuana users versus non-users (8.1% vs 0.5%, p<0.001). No significant differences in high-intensity drinking prevalence were observed by race/ethnicity or parental education.

Significant interactions between grade and race/ethnicity were observed (p=0.030). Models run separately by grade showed that among tenth grade students, white students reported significantly higher prevalence than non-white students (3.6% vs 2.4%, p=0.025). Among eighth grade students, high-intensity drinking prevalence was not significantly different for white and non-white students (0.9% vs 1.3%, p=0.246). No significant interactions were observed between grade and the other remaining covariates (gender, parental education, lifetime cigarette use, or lifetime marijuana use).

DISCUSSION

The majority of research examining high levels of alcohol consumption among adolescents has focused on “binge” or “heavy episodic drinking,” generally defined as having five or more drinks on a single occasion, or four or more for women and five or more for men.8 However, there is a growing recognition that many older adolescents and young adults drink well beyond the five or more level.1,6,8 The current study found a meaningful number of current younger adolescents also drink well beyond the five or more level. Applying the prevalence estimates found in the current study to estimates of U.S. school enrollment by grade9 indicates that approximately 40,000 eighth grade students and 113,000 tenth grade students in the U.S. consumed ten or more drinks in a single occasion at least once in the 2 weeks preceding the survey, which occurred in Spring 2016. These adolescents were drinking at levels that would raise adult blood alcohol concentration to at least four times the legal 0.08% limit,2 reaching severe and even life-threatening impairment levels.8 Animal research has indicated that, compared with adults, adolescents have higher sensitivity to alcohol’s stimulant effects and lower sensitivity to its sedation effects, making them more likely to initiate activities such as driving after drinking and more likely to drink to the point of coma.10 Heavy alcohol use during adolescence is associated with changes in brain function and structure and with increased risk for negative consequences across the lifespan.10,11 Therefore, understanding how many adolescents engage in high-intensity drinking and which adolescents are at risk for high-intensity drinking has important implications for public health. Future studies should also explore the types of consequences young drinkers experience when they have ten or more drinks in a row.

Limitations

The findings from the current study are subject to limitations. First, all data were based on self-report of consumption of ten or more drinks in a row. Respondents may have difficulty reporting the number of drinks consumed at such high levels, and use of a ten or more criterion means that hazardous drinking episodes falling between the five or more level (described elsewhere7) and ten or more level (described here) are not captured. Second, gender-specific drinking thresholds were not available, although girls likely become more intoxicated after the same number of drinks (because of differences in size and alcohol metabolism).

CONCLUSIONS

Despite its limitations, the current study provides the first opportunity to document the prevalence of high-intensity drinking among younger adolescents using current and nationally representative data. Results indicate that a concerning number of middle school and early high school students report current high-intensity drinking, and that these risks overlap with use of cigarettes and marijuana. Young adolescents having ten or more drinks in a row are clearly a very high-risk population; screening and intervention efforts that can identify such youth may prove to be effective in limiting later harms resulting from high levels of alcohol consumption.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by research grants R01AA023504 (to M. Patrick) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and R01DA001411 (to L. Johnston) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsors. The study sponsors had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

The manuscript was conceptualized and drafted by Dr. Patrick and Ms. Terry-McElrath. Ms. Terry-McElrath conducted statistical analyses. Drs. Patrick, Miech, O’Malley, Schulenberg, and Johnston directed data collection and critically reviewed the manuscript.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Patrick ME. A call for research on high-intensity alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(2):256–259. doi: 10.1111/acer.12945. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hingson RW, White A. Trends in extreme binge drinking among U.S. high school seniors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):996–998. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3083. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Kloska DD, Schulenberg JE. High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(9):1905–1912. doi: 10.1111/acer.13164. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM. High-intensity drinking by underage young adults in the United States. Addiction. 2017;112(1):82–93. doi: 10.1111/add.13556. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016. [Accessed January 15, 2017]. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Martz ME, et al. Extreme binge drinking among 12th-grade students in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1019–1025. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2392. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016. [Accessed January 15, 2017]. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Accessed November 28, 2016];Alcohol overdose: the dangers of drinking too much. 2015 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AlcoholOverdoseFactsheet/Overdosefact.htm.

- 9.Bauman KE, Davis J. SEHSD Working Paper 2014–7. U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. [Accessed November 28, 2016]. Estimates of school enrollment by grade in the American Community Survey, the Current Population Survey, and the Common Core of Data. www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2013/demo/acs-cps-ccd_02-18-14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. DHHS. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to prevent and reduce underage drinking. Rockville, MD: 2007. [Accessed January 15, 2017]. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44360/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Squeglia LM, Spadoni AD, Infante MA, et al. Initiating moderate to heavy alcohol use predicts changes in neuropsychological functioning for adolescent girls and boys. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(4):715–722. doi: 10.1037/a0016516. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]