Abstract

Activated lymphocytes perform a clonal balancing act, yielding a daughter cell that differentiates owing to intense PI3K signaling, alongside a self-renewing sibling cell with blunted anabolic signaling. Divergent cellular anabolism versus catabolism is emerging as a feature of several developmental and regenerative paradigms. Metabolism can dictate cell fate, in part, because lineage-specific regulators are embedded in the circuitry of conserved metabolic switches. Unequal transmission of PI3K signaling during regenerative divisions is reminiscent of compartmentalized PI3K activity during directed motility or polarized information flow in non-dividing cells. The diverse roles of PI3K pathways in membrane traffic, cell polarity, metabolism, and gene expression may have converged to instruct sibling cell feast and famine, thereby enabling clonal differentiation alongside self-renewal.

Keywords: asymmetric, PI3K, mTOR, anabolism, catabolism, self-renewal

Clonal Lymphocyte Regeneration Enabling Vertebrate Immunity

Lymphocytes are essential for survival in a world full of microbial and viral pathogens. Breach of our barrier surfaces and recognition of a foreign component triggers a rare lymphocyte with a matching antigen receptor to undergo massive clonal expansion. Many cellular descendants of B cells and T cells terminally differentiate into plasma cells and effector T cells, respectively. Other cellular progeny must remain less differentiated for renewed production of plasma cells and effector cells during persistent or recurrent infection. A variety of mechanisms, both deterministic and stochastic, have been invoked to explain the nature of lymphocyte diversification [1].

Recent evidence that unequal outcomes of proliferation or cell fate could be attributed to unequal nutritive signaling and mitochondrial dynamics in dividing stem cells, lymphocytes, and cancer cells [2-11] has converged with emerging evidence that metabolism plays deterministic roles in cellular fate and function in lymphocytes and many other cell types [2, 5, 7, 12-22]. This review will discuss recent advances in the regeneration of lymphocytes and how it has been seemingly patterned from an ancient duality of cellular feast and famine. A gradient of unequal PI3K signaling, used for directed migration [23, 24] and polarized function [25-28] in non-dividing cells, may have also been exploited by mitotic progenitors to instruct opposing metabolic and cell fate programs following cell division.

Signaling, Fate, and Function Reliant on Ad hoc Polarity

In contrast to many epithelial tissues, lymphocytes do not have constitutive or permanent polarity. Nonetheless, motile lymphocytes rely on provisional or facultative polarity to patrol lymphoid tissues in search of trophic ligands for survival and foreign antigens that recruit them for duty [29-32]. Activated lymphocytes also require facultative polarity to form immune synapses critical in signaling, as well as directional endocytosis or exocytosis as part of their essential functions [28, 31, 33]. Extrinsic polarity cues have also been implicated in the organization of asymmetric cell division of lymphocytes [29].

Because ancestral forms of asymmetric division in worms and flies utilize an evolutionarily conserved PAR network of polarity regulators [34], it was presumed that asymmetric cell division of lymphocytes would be heavily dependent on this pathway [35]. Much of the genetic evidence perturbing the PAR network in blood cells has yielded incomplete biological phenotypes, however, prompting some skepticism on the nature and importance of asymmetric lymphocyte division [36-39]. Significance of asymmetric cell division of lymphocytes has also been called into question by mathematical modeling suggesting that stochastic mechanisms, not deterministic processes, direct cell fate diversification in lymphocytes [40, 41]. Exploration of the cell biology of lymphocyte polarity in non-dividing cells has remained an active area of investigation. Whether asymmetric cell division has relevance to the signaling and transcriptional networks of lymphocyte differentiation, by contrast, has been more controversial.

Binary Metabolism as a Framework for Cellular Switching

One of the fundamental adaptations of unicellular life is the ability to change metabolic strategy to maintain cell and species survival. In single-celled microbes, choice of anabolism or catabolism is based on the availability or scarcity of nutrients, respectively [42, 43]. Our cells, continually bathed in nutrients through organismal metabolic homeostasis, are, instead, instructed by extrinsic signals to utilize the appropriate amount of nutrients for a quiescent or proliferative lifestyle.

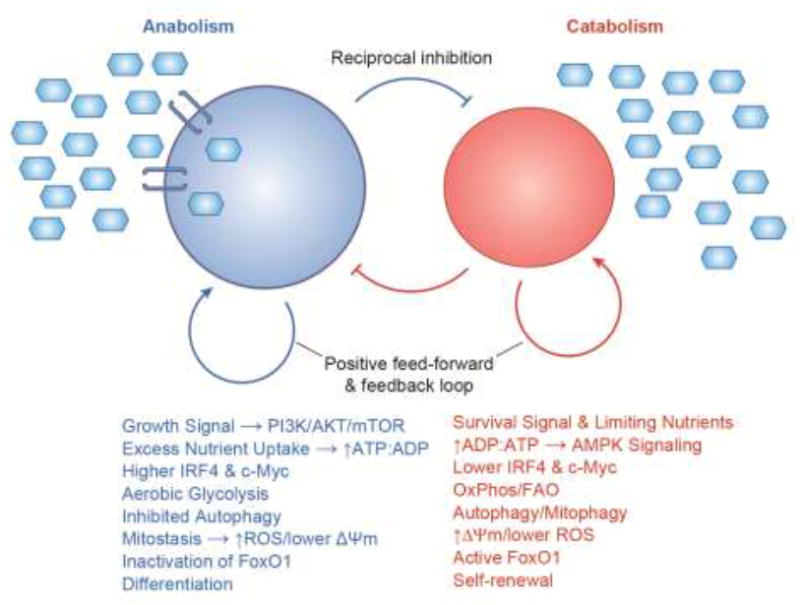

A major shift in the study of lymphocyte biology and immune cell signaling in the last decade-and-a-half has been the intense investigation of selective metabolic pathways in immune cell fate and function [42-45] (Figure 1). Emerging models point to a view that quiescent naïve and memory lymphocytes must engage in catabolic (or starvation) metabolism, including mitochondrial oxidative respiration, fatty acid oxidation, autophagy, and mitochondrial turnover and fission [2, 5, 7-9, 12, 42-51]. By contrast, the induction of proliferation and effector differentiation of lymphocytes is dependent on anabolic (or proliferative) metabolism, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, c-Myc induction, aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect), glutaminolysis, inhibited autophagy, mitochondrial stasis, and mounting induction of reactive oxygen species.

Figure 1. Metabolism is a bistable process that is suited to binary or branching cellular decisions.

In single-celled beings, nutrients are utilized when available for proliferative metabolism and when nutrients are limiting cells undertake a fundamentally different, starvation metabolism. In animals, some cells are in an anabolic and proliferative state because of strong growth factor signaling and licensure to take up excess nutrients, while some cells are in a catabolic and quiescent state owing to survival signaling with limiting nutrient uptake. Each state has feed-forward and feedback self-reinforcement and inhibits the processes of the other side. Consequently, perturbation of a subcomponent of one state topples that state and results in a switch to the other sate. Therefore, cells tend to be in equilibrium in one or the other state. For a non-dividing cell such a macrophage, phenotypic switching into inflammatory and non-inflammatory behavior is driven by anabolic versus catabolic signaling, respectively. For regenerative paradigms such as lymphocytes or epithelial replacement, anabolism and catabolism drive differentiation and self-renewal, respectively. The metabolic states appear deterministic of the cell fates because of interdependency in their signaling pathways. For example, lymphocyte self-renewal is wired into the PI3K pathway because FoxO1 maintains expression of key cell identity genes. Conversely, IRF4 drives lymphocyte differentiation because it plays an obligatory role in aerobic glycolysis and the anabolic switch required for proliferation and differentiation. Blue hexagons represent nutrients and blue transmembrane brackets represent nutrient transporters.

A striking aspect of metabolism in unicellular organisms and multi-cellular beings is its bi-stable nature (Figure 1). Anabolism and catabolism each reinforce its own processes with positive feed-forward/feed-back regulation and reciprocally inhibit the processes of the other type of metabolism [2, 42]. For example, glucose uptake, glycolytic flux, and ROS production maintain elevated PI3K/mTOR activation, inhibition of autophagy, and inactivation of FoxO1, as well as preventing AMPK activation. Conversely, limited nutrient utilization and oxidative metabolism maintains AMPK activation, self-digestion, mitochondrial turnover, preserved electron transport function, and FoxO1 nuclear activity. As a cellular process that tends to equilibrate into one of two states, signaling to feast and famine (i.e.- anabolic and catabolic metabolism) could be regarded as a useful logic for bifurcating other cellular outcomes.

Even in non-dividing cells, such as macrophages, anabolic and catabolic metabolism can be linked to diametrically opposing cell states [44]. Inflammatory stimuli such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides induce mTOR activation and aerobic glycolysis, with mitochondrial stasis and progressive loss of mitochondrial function. By contrast, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 blocks mTOR activation and glycolytic flux resulting in mitophagy and preserved function [20]. In a non-dividing cell, bistable metabolic logic can form a binary switching mechanism. In a mitotic progenitor, bistable metabolic logic, in combination with a mechanism to transmit an anabolic signal unequally during cell division, could conceivably form a bifurcation that yields two different cell types from one precursor, a hallmark of developmental biology.

Bifurcating Sibling Cell Metabolism and Cell Fate

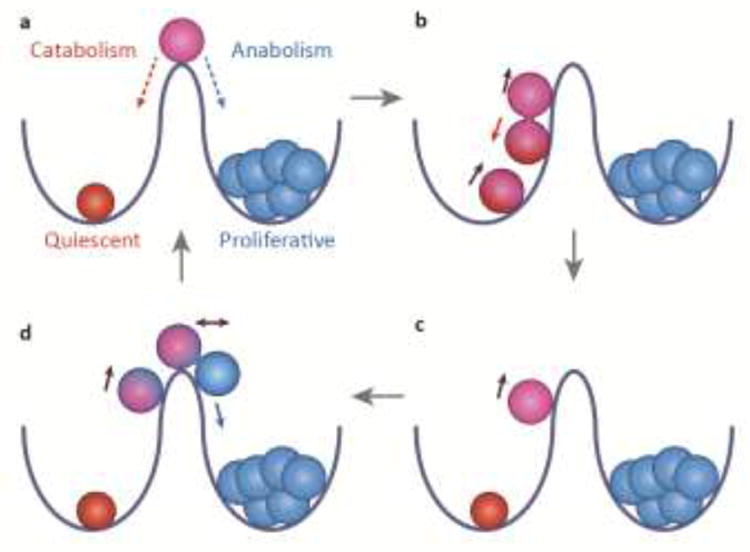

Single lymphocytes must balance differentiation and self-renewal, which apparently requires diametrically opposing metabolism. Recent identification of the stage at which activated lymphocytes undergo determined differentiation has provided evidence, at the clonal level, that an activated progenitor can be instructed to produce daughter cells with opposing metabolic behavior and cell fate (Figure 2). In mice undergoing immunization or challenged with infectious agents, proliferating B cells and T cells silence expression of a developmentally critical transcription factor after approximately four rounds of cell division [2, 5-7]. The silencing of Pax5 in B cells and TCF1 in T cells occurs late in the cell division cycle and is marked by one cell undergoing de novo gene silencing while its sibling cell remains Pax5-expressing or TCF1-expressing. Cells that silence expression of Pax5 or TCF1 do not regain expression and undergo progressive differentiation into plasma cells and effector T cells, respectively [2, 5-7]. Cells that retain expression of Pax5 or TCF1, and thus their developmental identity, remain bipotent, capable of continued differentiation and self-renewal (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hypothetical model for diversifying activation state and cell fate through asymmetric cell division.

(a) The two wells represent two states of metabolic equilibrium: the red cell is catabolic, quiescent, and undifferentiated; the blue cells are anabolic, proliferative and irreversibly differentiated. Purple cell at summit represents an unstable intermediate state that is more anabolic than the red cell but not irreversibly differentiated, thus capable of rolling backward or forward. (b, c) Upon activation, the red cell begins to roll uphill and divide. Asymmetric signaling during division produces a red daughter cell with weaker activation, which rolls back downhill, and purple daughter cell with stronger anabolic activation, which continues upward to summit. (d) The mitotic, anabolic, purple cell has also become asymmetric. After division, the purple cell, with lesser activation, balances at the summit and the more activated blue cell, which has crossed the threshold into irreversible differentiation, rolls forward downhill. The red cell might be considered a quiescent stem cell that does not directly produce a fully differentiated cell. The purple cell might be considered an active progenitor --- more proliferative and anabolic than the red cell, but not yet irreversibly differentiated. The blue cell cannot roll backwards under physiological conditions because it has undergone irreversible differentiation, although the blue cells will eventually become post-mitotic.

The possibility that discordant silencing of a key transcription factor by sibling lymphocytes might represent unequal transmission of metabolic instruction was suggested by the findings that the transcription factor FoxO1 positively regulates expression of the genes encoding Pax5 and TCF1 ([5] and references therein). Anabolic PI3K signaling transduced through a lymphocyte’s antigen and costimulatory receptors activates AKT, which, in turn, can displace FoxO1 from the nucleus. At the clonal level, nuclear exclusion of FoxO1 is evident in Pax5- or TCF1-silenced cells, with discordant nuclear retention of FoxO1 in the self-renewing sibling cell [5]. Asymmetric anabolic signaling in dividing cells, thus, impinges on cell fate because the transcription factor networks of lymphocyte self-renewal versus differentiation converge with the downstream parts of the same signaling switch used to regulate organismal and cellular metabolism --- PI3K/AKT-driven inactivation of FoxO1, the instruction to abandon catabolism and initiate anabolism.

The first three cell divisions of B cells and T cells also exhibit asymmetry of anabolic signaling between sibling cells, with one sibling cell more proliferative and the other more quiescent [5, 6, 8, 9, 35]. In those early divisions, however, the more activated sibling has yet to silence Pax5 or TCF1 and is, thus, merely specified (in a reversible manner) to be an activated progenitor of plasma cells or effector T cells, respectively [2, 5, 6] (Figure 2). When the activated progenitor produces a daughter with silenced Pax5 or TCF1 alongside a less anabolic sibling that remains a progenitor, the more differentiated cell is determined because of the irreversible nature of the silencing.

In addition to FoxO1, there are other lineage-determining transcription factors of lymphocytes that play dual roles as essential mediators of selective metabolism. IRF4, for example, induces gene expression changes required for plasma cell and effector T cell differentiation, and is also an essential inducer of glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes in differentiating lymphocytes [2, 5, 52, 53]. Consequently, activated cells deficient in IRF4 are poorly proliferative, overly catabolic, and unable to differentiate into plasma cells and effector T cells [2, 5, 52, 53]. Conversely, Bcl-6, a transcription factor associated with maintenance of lymphocyte identity at the expense of terminal differentiation, negatively regulate aerobic glycolysis [54], consistent with the correlation that Bcl-6-expressing B cells and T cells maintain expression of Pax5 and TCF1, respectively. After immunization, reciprocal expression of FoxO1, Bcl-6, and Pax5 in germinal center B cells versus IRF4 and transient c-Myc in nascent plasmablasts [5, 47-49, 51] reflects the metabolic balancing act of restrained versus unmitigated anabolism of progenitor versus differentiated progeny, respectively (Figure 2).

If polarized outcomes between sibling lymphocytes can be achieved by virtue of gene networks that are interwoven into anabolic and catabolic signaling mechanisms, it is possible that other developmental and regenerative bifurcations may have arisen from unequal nutritive signaling. Recent examination of several regenerative systems, including lymphocytes and mammary, hematopoietic, muscle, intestinal, and neural stem cells has begun to suggest that autophagy or elimination of older mitochondria, biogenesis and fusion of new organelle, along with efficient oxidative metabolism and low ROS levels are critical processes for self-renewal and cellular quiescence [2, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 55-57]. Reciprocally, mitochondrial stasis, aerobic glycolysis, and ROS production have been associated with greater activation, differentiation and cellular senescence.

Polarizing Nutritive Signaling across Cell Divisions

The findings of unequal abundance or activation of PI3K, AKT, mTOR, c-Myc, proteasomes, autophagosomes, and aged mitochondria in normal and transformed sibling cells suggest the possibility that there may be an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for partitioning nutritive signaling in mitosis [2, 4-11, 58]. Extrinsic signaling to a focal area of an interphase lymphocyte results in actin and tubulin cytoskeletal rearrangements and polarized clustering of receptors [8, 27, 28, 31, 35]. Activating receptors co-localize with the centrosome at the site of extrinsic signaling, while inhibitory molecules arrange diametrically opposite at the distal side from the contact. Interphase polarity can extend through mitosis and cytokinesis with the mitotic spindle remaining oriented to the site of stimulation [35]. Coordinated arrangement of signaling molecules to one side of the spindle offers a plausible way for unequal extrinsic signaling to be delivered to the two daughter cells that arose from a focused area of stimulation [35, 58, 59]. Asymmetric extrinsic signaling can render sibling cells unequal in transcription, translation, post-translational modifications, and organelle dynamics prior to the completion of cytokinesis, a phenomenon not unique to lymphocytes [2, 4, 5, 7-9, 11, 60].

Lymphocytes are also capable of propagating signaling from antigenic activation through the space and time of subsequent cell divisions, leading to extensive proliferation and differentiation of subsequent generations of cells that have not contacted antigen directly [61, 62]. Although the cellular inheritance of signaling is not completely understood, endocytosis of antigen receptors sustains activation [63] and plays an essential role in anabolic induction of both B and T lymphocytes [64, 65]. In B cells, polarity of endocytosed antigen can transcend cell division [33]. Endocytic trafficking has also been implicated in asymmetric division in flies, and in a manner that occurs independently of the conserved polarity network [66]. Polarizing cues responsible for unequal signaling and discordant silencing of Pax5 or TCF1 in later cell divisions that may not be directly triggered by focal antigen receptor ligation remain to be defined (see Outstanding Questions). It is possible, for example, that homotypic adhesion and synapses between lymphocytes, which has been functionally implicated in subsequent divisions and differentiation, may serve as later-generation extrinsic polarity cues [67, 68].

PI3K Pathway as a Conserved Regulator of Cellular Asymmetry

The PI3K pathway began in single-celled eukaryotes as a regulator of vesicular trafficking (a single class III PI3K molecule). With the evolution of class I and class II PI3K molecules, the PI3K pathway expanded its roles to extrinsic signaling, metabolism, polarity, endocytosis, and membrane trafficking [69, 70]. A common theme in PI3K-associated cell polarity is the formation of spatially compartmentalized signaling activity that intersects with regionalized actin dynamics and microtubule cytoskeleton orientation (Figure 3). Dyctostelium cells (and vertebrate neutrophils) undergo directed migration by the insertion of PI3K molecules into the leading edge, thereby producing compartmentalized actin rearrangement [23, 24, 71, 72]. Reciprocally, the inhibitory phosphatase PTEN (or SHIP-1) localizes to the lagging side of the cell. Neurons undergo axonal outgrowth through PI3K-mediated guidance cues, which can be antagonized by the AMPK pathway [71, 73, 74]. Epidermal progenitors undergo apical PI3K-induced polarity and asymmetric division [75]. All of these scenarios are reminiscent of lymphocyte activation with its diametrically opposite arrangement of proximal PI3K activity and distal inhibitory phosphatases [26, 27, 31, 35] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Asymmetric PI3K signaling is an evolutionarily conserved regulator of cell polarity.

Spatially restricted domains of PI3K activity (blue lines) are characteristic of numerous forms of symmetry-breaking. Usually in response to an extrinsic cue, a self-reinforcing signaling domain is nucleated by the concerted actions of PI3K and regulated actin remodeling. A common feature of these systems is having diametrically opposite localization of negatively-acting domains (red lines) that dampen PI3K activity or stabilize actin. Centrosome and microtubule organizing centers (black) are often polarized and act as hubs or counterbalances to the polarized PI3K activity and actin dynamics. Processes as diverse as directed cell migration, neuronal polarity, apico-basal polarity, asymmetric division, and lymphocyte activation, function, and regeneration are controlled in this manner. It is speculated that activating recycling endosomes (blue ovals) maintain an asymmetric position at one end of the spindle pole, leading to asymmetric inheritance of signaling endosomes during mitosis.

Concluding Remarks

The ability of the PI3K signaling pathway to control processes as diverse as gene expression, metabolism, proliferation, polarity, and membrane traffic can apparently converge to enable a cell receiving an anabolic signal to reliably deliver that signal unequally to its two cellular progeny (Figure 4, Key Figure). The nature and pervasiveness of signaling to unequal cellular outcomes will require further exploration (see Outstanding Questions). Although the PAR polarity network that is commonly associated with apico-basal polarity and asymmetric division was presumed to be the chief architect of lymphocyte asymmetric division, mounting evidence suggests that phospholipid polarity signaling may, instead or in addition, be an integral piece of the puzzle [21, 30, 31, 34, 36-39, 75]. To what extent the PI3K-dependent cell polarity network may intersect with the PAR polarity network still needs to be determined (see Outstanding Questions). It is speculated that there may be many other developmental branch points in complex beings whereby lopsided metabolic signaling drives feast versus famine and asymmetric cell fates.

Figure 4. Key Figure. Diverse roles of PI3K signaling may converge to shape the logic of cell fate branches.

The ability of PI3K-mediated membrane trafficking and polarity to function in in concert with other PI3K activities, such as cell growth, proliferation, metabolism and gene regulation, may underlie the ability of progenitor cells to differentiate and self-renew (or create two different types of differentiated daughter cells). Asymmetric cell divisions are an integral process in metazoan growth and repair. Seemingly, not all instances of asymmetric division are dependent on the PAR polarity network. It is speculated that a metabolic asymmetry network may represent a complementary or cooperative system to ensure unequal outcomes from a cell division.

Trends.

Lymphocyte differentiation and self-renewal have been causally linked to opposing metabolic states, anabolism and catabolism, respectively. Apparently, some lineage-specific gene switches have exploited circuitry of conserved metabolic switches.

Asymmetric cell division in activated lymphocytes produces discordant outcomes of nutritive signal transduction. One daughter cell appears to fully activate the PI3K pathway while its sibling cell undergoes blunted anabolic signaling.

Asymmetric lipid signaling is conserved across many forms of cell polarity, including directed migration, neuronal polarity, and the immunological synapse between a lymphocyte and its activating ligand.

Seemingly unrelated PI3K-mediated functions, such as cellular polarity and metabolic regulation, can apparently converge to balance the opposing demands of stem cells, to differentiate and self-renew.

Outstanding Questions.

Why are the first three or four lymphocyte divisions characterized by anabolic inequality, with a more active and a more quiescent daughter cell, but both daughters still below the threshold for irreversible differentiation?

What role does the conserved PAR network play in the divisions characterized by asymmetric PI3K signaling?

What are the polarity mechanisms responsible for asymmetric PI3K transmission in cell divisions without an apparent extrinsic polarity cue?

Is T cell exhaustion and clonal depletion, associated with chronic viral infection and cancer, a consequence of prolonged anabolism, and, if so, can it be rescued with anti-anabolic drugs such as mTOR inhibitors or AMPK agonists?

Over how many cell divisions can endocytosed antigen receptors continue to signal?

Do other cells that undergo lineage branches without an extrinsic polarity cue such as blood progenitors, use asymmetric PI3K signaling to differentiate and self-renew?

Do intestinal stem cells that depend on oxidative metabolism and Paneth cells that use aerobic glycolysis arise from a metabolically asymmetric cell division?

Do cancer cells with proliferative and regenerative heterogeneity undergo asymmetric PI3K signaling?

Acknowledgments

S.L.R. is grateful to Morgan Huse, Russell Jones, Erika Pearce, Jeff Rathmell, Craig Thompson, and Matthew Vander Heiden for stimulating discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Reiner SL, Adams WC. Lymphocyte fate specification as a deterministic but highly plastic process. Nature reviews Immunology. 2014;14:699–704. doi: 10.1038/nri3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams WC, et al. Anabolism-Associated Mitochondrial Stasis Driving Lymphocyte Differentiation over Self-Renewal. Cell reports. 2016;17:3142–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arsenio J, et al. Early specification of CD8+ T lymphocyte fates during adaptive immunity revealed by single-cell gene-expression analyses. Nature immunology. 2014;15:365–372. doi: 10.1038/ni.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dey-Guha I, et al. Asymmetric cancer cell division regulated by AKT. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:12845–12850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109632108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin WW, et al. Asymmetric PI3K Signaling Driving Developmental and Regenerative Cell Fate Bifurcation. Cell reports. 2015;13:2203–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin WW, et al. CD8+ T Lymphocyte Self-Renewal during Effector Cell Determination. Cell reports. 2016;17:1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nish SA, et al. CD4+ T cell effector commitment coupled to self-renewal by asymmetric cell divisions. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2017;214:39–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollizzi KN, et al. Asymmetric inheritance of mTORC1 kinase activity during division dictates CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Nature immunology. 2016;17:704–711. doi: 10.1038/ni.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verbist KC, et al. Metabolic maintenance of cell asymmetry following division in activated T lymphocytes. Nature. 2016;532:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature17442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan TL, et al. Cell-to-cell variability in PI3K protein level regulates PI3K-AKT pathway activity in cell populations. Current biology : CB. 2011;21:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katajisto P, et al. Asymmetric apportioning of aged mitochondria between daughter cells is required for stemness. Science. 2015;348:340–343. doi: 10.1126/science.1260384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng M, et al. Aerobic glycolysis promotes T helper 1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism. Science. 2016;354:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buck MD, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics controls T cell fate through metabolic programming. Cell. 2016;166:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Colman MJ, et al. Interplay between metabolic identities in the intestinal crypt supports stem cell function. Nature. 2017;543:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature21673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho TT, et al. Autophagy maintains the metabolism and function of young and old stem cells. Nature. 2017;543:205–210. doi: 10.1038/nature21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu P, et al. FGF-dependent metabolic control of vascular development. Nature. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nature22322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong BW, et al. The role of fatty acid beta-oxidation in lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2017;542:49–54. doi: 10.1038/nature21028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito K, et al. Self-renewal of a purified Tie2+ hematopoietic stem cell population relies on mitochondrial clearance. Science. 2016;354:1156–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Prat L, et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature. 2016;529:37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature16187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ip WKE, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science. 2017;356:513–519. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang CH, et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buck MD, et al. Metabolic Instruction of Immunity. Cell. 2017;169:570–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funamoto S, et al. Spatial and temporal regulation of 3-phosphoinositides by PI 3-kinase and PTEN mediates chemotaxis. Cell. 2002;109:611–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iijima M, Devreotes P. Tumor suppressor PTEN mediates sensing of chemoattractant gradients. Cell. 2002;109:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franco I, et al. PI3K class II alpha controls spatially restricted endosomal PtdIns3P and Rab11 activation to promote primary cilium function. Developmental cell. 2014;28:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalil AM, et al. B cell receptor signal transduction in the GC is short-circuited by high phosphatase activity. Science. 2012;336:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1213368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Floc’h A, et al. Annular PIP3 accumulation controls actin architecture and modulates cytotoxicity at the immunological synapse. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:2721–2737. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stinchcombe JC, et al. Mother Centriole Distal Appendages Mediate Centrosome Docking at the Immunological Synapse and Reveal Mechanistic Parallels with Ciliogenesis. Current biology : CB. 2015;25:3239–3244. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arsenio J, et al. Asymmetric Cell Division in T Lymphocyte Fate Diversification. Trends in immunology. 2015;36:670–683. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yassin M, Russell SM. Polarity and asymmetric cell division in the control of lymphocyte fate decisions and function. Current opinion in immunology. 2016;39:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huse M. Lymphocyte polarity, the immunological synapse and the scope of biological analogy. Bioarchitecture. 2011;1:180–185. doi: 10.4161/bioa.1.4.17594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin-Cofreces NB, et al. Immune synapse: conductor of orchestrated organelle movement. Trends in cell biology. 2014;24:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thaunat O, et al. Asymmetric segregation of polarized antigen on B cell division shapes presentation capacity. Science. 2012;335:475–479. doi: 10.1126/science.1214100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein B, Macara IG. The PAR proteins: fundamental players in animal cell polarization. Developmental cell. 2007;13:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang JT, et al. Asymmetric T lymphocyte division in the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Science. 2007;315:1687–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1139393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawkins ED, et al. Regulation of asymmetric cell division and polarity by Scribble is not required for humoral immunity. Nature communications. 2013;4:1801. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metz PJ, et al. Regulation of asymmetric division and CD8+ T lymphocyte fate specification by protein kinase Czeta and protein kinase Clambda/iota. J Immunol. 2015;194:2249–2259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metz PJ, et al. Regulation of Asymmetric Division by Atypical Protein Kinase C Influences Early Specification of CD8(+) T Lymphocyte Fates. Scientific reports. 2016;6:19182. doi: 10.1038/srep19182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sengupta A, et al. Atypical protein kinase C (aPKCzeta and aPKClambda) is dispensable for mammalian hematopoietic stem cell activity and blood formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:9957–9962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103132108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchholz VR, et al. T Cell Fate at the Single-Cell Level. Annual review of immunology. 2016;34:65–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duffy KR, et al. Activation-induced B cell fates are selected by intracellular stochastic competition. Science. 2012;335:338–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1213230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson CB. Rethinking the regulation of cellular metabolism. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 2011;76:23–29. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2012.76.010496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vander Heiden MG, et al. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence. Immunity. 2013;38:633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearce EL, et al. Fueling immunity: insights into metabolism and lymphocyte function. Science. 2013;342:1242454. doi: 10.1126/science.1242454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frauwirth KA, et al. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity. 2002;16:769–777. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calado DP, et al. The cell-cycle regulator c-Myc is essential for the formation and maintenance of germinal centers. Nature immunology. 2012;13:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni.2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dominguez-Sola D, et al. The proto-oncogene MYC is required for selection in the germinal center and cyclic reentry. Nature immunology. 2012;13:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/ni.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dominguez-Sola D, et al. The FOXO1 Transcription Factor Instructs the Germinal Center Dark Zone Program. Immunity. 2015;43:1064–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medzhitov R. Bringing Warburg to lymphocytes. Nature reviews Immunology. 2015;15:598. doi: 10.1038/nri3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sander S, et al. PI3 Kinase and FOXO1 Transcription Factor Activity Differentially Control B Cells in the Germinal Center Light and Dark Zones. Immunity. 2015;43:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahnke J, et al. Interferon Regulatory Factor 4 controls TH1 cell effector function and metabolism. Scientific reports. 2016;6:35521. doi: 10.1038/srep35521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Man K, et al. The transcription factor IRF4 is essential for TCR affinity-mediated metabolic programming and clonal expansion of T cells. Nature immunology. 2013;14:1155–1165. doi: 10.1038/ni.2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oestreich KJ, et al. Bcl-6 directly represses the gene program of the glycolysis pathway. Nature immunology. 2014;15:957–964. doi: 10.1038/ni.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luchsinger LL, et al. Mitofusin 2 maintains haematopoietic stem cells with extensive lymphoid potential. Nature. 2016;529:528–531. doi: 10.1038/nature16500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khacho M, et al. Mitochondrial Dynamics Impacts Stem Cell Identity and Fate Decisions by Regulating a Nuclear Transcriptional Program. Cell stem cell. 2016;19:232–247. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Sullivan TE, et al. BNIP3- and BNIP3L-Mediated Mitophagy Promotes the Generation of Natural Killer Cell Memory. Immunity. 2015;43:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang JT, et al. Asymmetric proteasome segregation as a mechanism for unequal partitioning of the transcription factor T-bet during T lymphocyte division. Immunity. 2011;34:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barnett BE, et al. Asymmetric B cell division in the germinal center reaction. Science. 2012;335:342–344. doi: 10.1126/science.1213495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Habib SJ, et al. A localized Wnt signal orients asymmetric stem cell division in vitro. Science. 2013;339:1445–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.1231077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaech SM, Ahmed R. Memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: initial antigen encounter triggers a developmental program in naive cells. Nature immunology. 2001;2:415–422. doi: 10.1038/87720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Stipdonk MJ, et al. Naive CTLs require a single brief period of antigenic stimulation for clonal expansion and differentiation. Nature immunology. 2001;2:423–429. doi: 10.1038/87730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yudushkin IA, Vale RD. Imaging T-cell receptor activation reveals accumulation of tyrosine-phosphorylated CD3zeta in the endosomal compartment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:22128–22133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016388108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willinger T, et al. Dynamin 2-dependent endocytosis sustains T-cell receptor signaling and drives metabolic reprogramming in T lymphocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:4423–4428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504279112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chaturvedi A, et al. Endocytosed BCRs sequentially regulate MAPK and Akt signaling pathways from intracellular compartments. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/ni.2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Emery G, et al. Asymmetric Rab 11 endosomes regulate delta recycling and specify cell fate in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell. 2005;122:763–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Severinson E, Westerberg L. Regulation of adhesion and motility in B lymphocytes. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2003;58:139–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gerard A, et al. Secondary T cell-T cell synaptic interactions drive the differentiation of protective CD8+ T cells. Nature immunology. 2013;14:356–363. doi: 10.1038/ni.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Engelman JA, et al. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nature reviews Genetics. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marat AL, Haucke V. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphates-at the interface between cell signalling and membrane traffic. The EMBO journal. 2016;35:561–579. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berzat A, Hall A. Cellular responses to extracellular guidance cues. The EMBO journal. 2010;29:2734–2745. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoo SK, et al. Differential regulation of protrusion and polarity by PI3K during neutrophil motility in live zebrafish. Developmental cell. 2010;18:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barnes AP, Polleux F. Establishment of axon-dendrite polarity in developing neurons. Annual review of neuroscience. 2009;32:347–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amato S, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates neuronal polarization by interfering with PI 3-kinase localization. Science. 2011;332:247–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1201678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dainichi T, et al. PDK1 Is a Regulator of Epidermal Differentiation that Activates and Organizes Asymmetric Cell Division. Cell reports. 2016;15:1615–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]