Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) often causes persistent infection, and is an increasingly important factor in the etiology of fibrosis/cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), although the mechanisms for the disease processes remain unclear. We have shown previously that HCV infection generates epithelial mesenchymal transition state (EMT) and tumor initiating cancer stem-like cells (TISCs) in human hepatocytes. In this study, we investigated whether HCV induced TISC when implanted into mice activate stromal fibroblasts. A number of fibroblast activation markers, including metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 were significantly increased at the mRNA or protein level in the xenograft tumors, suggesting the presence of tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs). Fibroblast activation markers of murine origin were specifically increased in tumor, suggesting that fibroblasts are migrated to form stroma. Next, we demonstrated that the conditioned medium (CM) from HCV infected human hepatocytes activates fibrosis related markers in hepatic stellate cells. We further observed that these HCV infected hepatocytes express TGF-β which activates stromal fibroblast markers. Subsequent analysis suggest anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibody, when incubated with CM from HCV infected hepatocytes, inhibits fibrosis marker activation in primary human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).

Conclusion

HCV infected hepatocytes induce local fibroblast activation by secretion of TGF-β, and preneoplastic or tumor state of the hepatocytes influences the network for TAF environment.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, hepatocytes, transforming growth factor, hepatic stellate cells, tumor associated fibroblasts

INTRODUCTION

HCV often causes persistent infection, and is an important factor in the etiology of fibrosis/cirrhosis and HCC (1, 2, 3). Although HCV primarily infects and replicates in hepatocytes, they impair normal functions of other liver cells and promote fibrosis/cirrhosis. Direct acting antiviral agents (DAAs) may significantly improve the outcome from HCV infection if detected early after infection, but treatment is costly and already faces issues such as viral mutation, relapse, and reinfection following therapy. Some patients still progress to liver failure and/or carcinoma despite being cured of HCV infection after therapy (4, 5, 6). HCV associated HCC is normally seen in the presence of fibrosis/cirrhosis, although the mechanism of this association is unclear at present. HCV genome does not integrate into its host genome, and has a predominantly cytoplasmic life cycle. Therefore, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis and HCC appear to involve mechanisms induced from HCV replication. We have previously shown that HCV infection of primary human hepatocytes promotes EMT related gene expression, and generates TISCs (7, 8).

Desmoplasia is the growth of fibrous or connective tissue that usually occurs around a malignant neoplasm, causing dense fibrosis around the tumor. Myofibroblasts are increasingly recognized as a cell type within the tumor microenvironment that impact tumor growth. These cells are integral for fibronectin fibril assembly and contribute importantly to matrix stiffness and tumor desmoplasia (9). The tumor microenvironment, including stromal myofibroblasts and associated matrix proteins, regulate cancer cell proliferation and invasion (10). Quiescent stellate cells undergo activation to adopt fibroblast morphology and secrete type I collagen, the principal matrix protein responsible for the development of liver fibrosis, and cancer progression (11, 12). Activated HSCs are also a rich source of growth factors and cytokines that promote tumor progression and angiogenesis (13). Additionally, they regulate extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover and suppress anti-tumor immune response, creating a pro-metastatic microenvironment for tumor cells. Antifibrotic effects may therefore result either from a direct effect on fibrogenic cells or from non-specific anti-inflammatory effects.

Quiescent stellate cell activation may occur from TGF-β secreted by EMT/pre-neoplastic hepatocytes. TGF-βs are multifunctional cytokines and regulate a broad range of biological processes, including cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation (14). The three isoforms, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3, have sequence homology, bind to the same receptors, although their in vivo functions reveal striking differences, with unique biological importance and functional non-redundancy. Both TGF-β1/β2 paly a role in immune tolerance and induce fibrosis, while TGF-β3 counteracts tissue fibrosis (15). TGF-β from polarized M2 macrophages also play a role in fibrotic processes (16, 17). In this study, we examined how HCV infection activates hepatic stellate cells in promoting desmoplasia. Implantation of HCV associated TISCs were examined for enhancement of tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs) in a xenograft model. Our results demonstrated that HCV infected human heaptocytes secreting TGF-β induced cellular microenvironment promoting induction of fibroblast activation for stromal changes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) were generated by transfection of a plasmid DNA expressing HCV core genomic region of genotype 1a (Genbank accession number M62321) into primary human hepatocytes under the control of a CMV promoter (18). Cells of human hepatocyte origin (Huh7.5 and Huh7.5 cells harboring the HCV genotype 2a genome-length replicon with the Renilla luciferase reporter gene (Rep2a-Rluc cells, kindly provided by Hengli Tang, Florida State University), human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) and human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were used. Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Immortalized human hepatic stellate cells, LX2 (19), (kindly provided by Scott Friedman, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY), were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Primary human hepatic stellate cells were procured (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA) and grown on poly-L-lysine-coated flasks in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and 2X L-glutamine at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. IHH were infected with cell culture-grown HCV genotype 2a (clone JFH1) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2, and examined for phenotypic and molecular changes.

Xenograft mouse model

TISCs generated from HCV infected late passage IHH were implanted into flanks of NSG mice (N=4) for tumor growth as described previously (7). Mice were sacrificed when tumor volume reached to ~ 1.2 cm3, and fibrosis markers were analyzed in xenografted tumors by quantitative real-time PCR or Western blot analysis.

Treatment of HSCs

Hepatic stellate cells were treated with CM from HCV infected hepatocytes, TGF-β1 (2.5, 5, or 10 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis) or TGF-β2 (5, 10, or 20 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis). Whenever necessary, HSCs were treated with CM neutralized by antibody to TGF-β1 (2 μg/ml) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or TGF-β2 (2 μg/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis), or negative control antibody for 24h, and RNA was isolated for subsequent analysis.

Western blot analysis

Proteins in cell lysates were separated and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The blot was blocked with 5% skim milk and incubated with a specific primary antibody as a probe, followed by treatment with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membrane was probed with antibodies to Vimentin (Cell Signaling), FSP-1 (EMD Millipore), α-SMA and MMP2 (Santa Cruz), TGF-β1 (Abcam) and TGF-β2 (R&D Systems). The membrane was reprobed with actin or GAPDH as an internal control. The protein band was detected with SuperSignal West Pico ECL reagents (Pierce). The densitometric scanning of Western blot was performed by ImageJ software (NIH).

Qualitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated by using a Trizol (Qiagen, CA). RNA was quantified by using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was synthesized by using random hexamers and a Superscript III reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, CA). qRT-PCR was performed with cDNA using TaqMan gene expression PCR master mix and 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-MGB primers for mouse ACTA2 (assay ID, Mm00725412_s1), COL1A2 (assay ID, Mm00483888_m1), COL1A1 (assay ID, Mm00801666_g1), CTGF (assay ID, Mm01192933_g1), Vimentin (assay ID, Mm01333430_m1), FSP-1 (assay ID, Mm00803372_g1), 18S RNA (assay ID, Mm04277571_s1). FAM-MGB primers for human ACTA2 (assay ID, Hs00426835_g1), TGFβ1 (assay ID, Hs00998133_m1), TGFβ2 (assay ID, Hs00234244_m1), TGFβ3 (assay ID, Hs01086000_m1), COL1A1 (assay ID, Hs00164004_m1), MMP2 (assay ID, Hs01548727_m1), CTGF (assay ID, Hs01026927_g1) and 18S rRNA (assay ID, Hs03928985_g1) as an endogenous control were used. The relative gene expression levels were normalized to the 18S rRNA level by using the 2-ΔΔCT formula (ΔΔCT = ΔCT sample − ΔCT untreated control). Commercially available control liver RNAs (C1 and C2) (Clonetics, CA and CloneTech, CA) were procured and used in this study for comparison.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as means ± standard deviations. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test with a two-tailed distribution. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Xenograft tumors from HCV induced TISCs recruit and activate murine fibroblasts

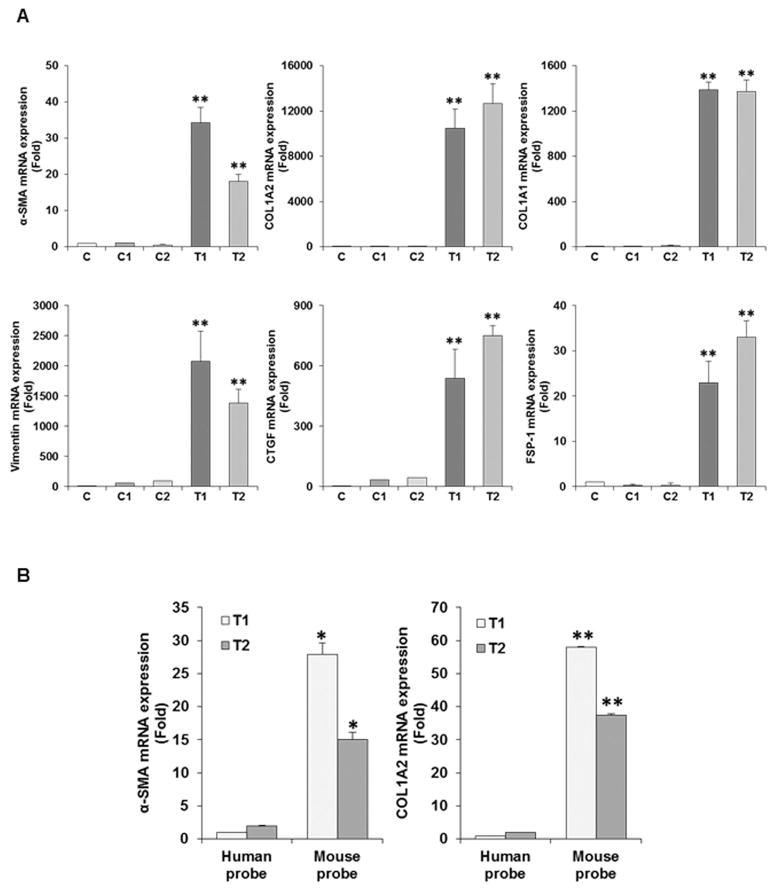

HCV infection in human liver induces fibrosis/cirrhosis and relate to an annual risk of approximately 1% for HCC (20). We generated xenograft multinodular tumors by implanting TISCs into NSG mice and dissected the tumors for biochemical analysis. To examine TAF marker expression, RNA was isolated from portion of the representative tumors (T1 and T2). HCV induced TISCs (C) and commercially available control liver (C1 and C2) RNAs were used for comparison. Expression of α-SMA, COL1A2, COL1A1, Vimentin, CTGF and FSP-1 mRNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1, panel A). RNAs from C, C1 or C2 did not exhibit the presence of TAF markers as compared to RNA from xenogarft tumors (T1 or T2). We observed a significantly higher expression level of mRNAs in tumors for collagen and a type III intermediate filament protein vimentin (>1000 fold), a matricellular protein CTGF (>400 fold), and α-SMA and FSP-1 (>20 fold). Next, we verified whether activation of these fibroblast markers are from recruitment of mouse fibroblast to implanted human hepatocytes. For this, we examined for amplification of α-SMA and COL1A2 in xenograft tissue by using mouse or human specific primers by qRT-PCR. Interestingly, the expression of α-SMA or COL1A2 gene was specifically recognized by mouse specific primers, whereas human specific primers did not show any significant amplification (Fig. 1, panel B). Thus, our results suggest that murine fibroblasts were recruited and activated by xenograft tumors.

Fig. 1. Analyses for TAF activation markers in xenograft tumors after implantation of TISCs into NSG mice.

RNA from xenograft tumors (T1 and T2) was isolated and analyzed for expression of α-SMA, COL1A2, COL1A1, Vimentin, CTGF, and FSP-1 by qRT-PCR and normalized with 18SRNA (Panel A). TISCs grown on petridish (C) and control human liver (C1 and C2) RNAs were used for comparison. Species specific analysis of TAF activation markers in xenograft tumors (panel B). RNA from T1 or T2 tumors was analyzed for expression of α-SMA and COL1A2 using mouse and human specific primers. Statistical significance of the results was analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test: *P < 0.05, **P<0.01.

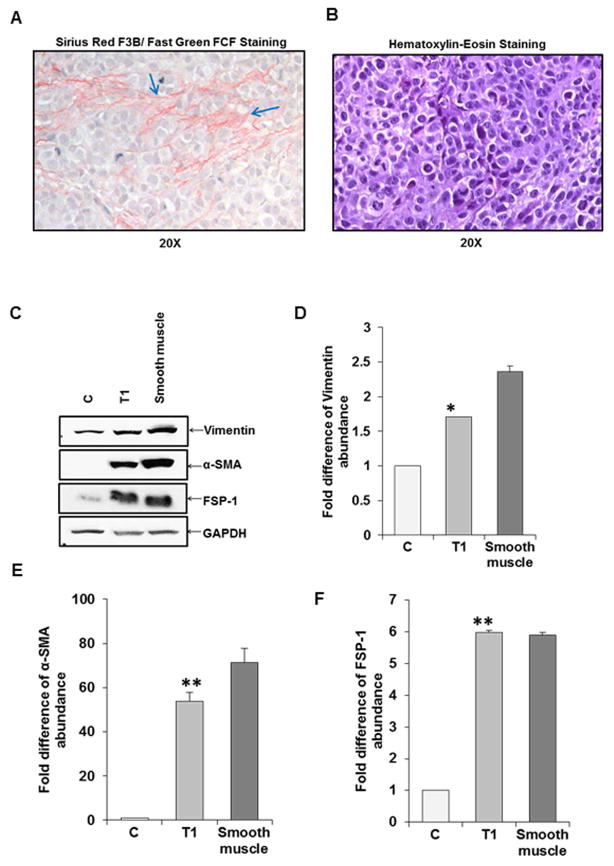

Xenograft tumors enhance CAF related proteins

We examined formalin fixed xenograft tumor sections for architectural changes. Tumor sections were stained with Sirius Red for collagen, and separately stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Sirius Red staining exhibited collagen fibers (Fig. 2, panel A), while H&E stained cells appeared as blue in a violet background composed of hepatocytes with nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 2, panel B). TAF marker proteins in xenograft tumors were separately examined from tumor lysates by Western blot analysis. TISCs (C) and mouse smooth muscle were used as controls. An increase in total Vimentin, α-SMA, and FSP-1 protein levels was observed (Fig. 2, panel C). The α-SMA protein was undetectable from TISCs (C), as expected. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping protein for normalization. Densitometric scanning results for expression differences of these marker proteins are also shown (Fig. 2, panels D–F). Our results clearly suggested an up-regulation of fibroblast markers at the protein level in xenograft tumors.

Fig. 2. Collagen fiber staining and TAF related protein expression status in xenograft tumor.

Staining with Sirus Red/Fast green of representative tumor section exhibiting collagen fibers are indicated by arrows (panel A). H&E staining of cells used for implantation and tumor generation is shown separately (panel B). Tumor lysates was analyzed for expression of vimentin, α-SMA, and FSP-1 by Western blot using specific antibodies (panel C). TISCs (C) or smooth muscle lysates was used as control for comparison. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping protein. Densitometric scanning of Western blot results are shown (panels D, E and F). Value from C was arbitrarily chosen as 1. Values represent mean from three independent experiments ±SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test: *P < 0.05, **P<0.01.

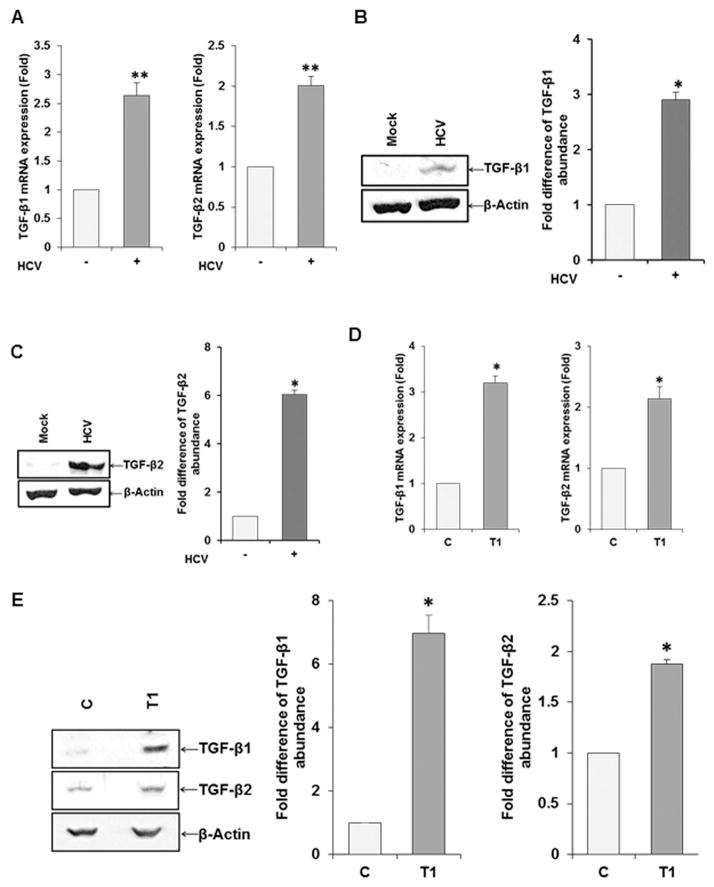

TGF-β is significantly upregulated in HCV infeted hepatocytes

Primary human hepatocytes displaying EMT after HCV infection modulates cytokine, transcription factor and metalloproteinase mRNA synthesis (8). Our transcriptome analysis results indicated that a number of important molecules, including TGF-β and MMP2 were elevated in HCV infected hepatocytes. TGF-β is a multifunctional cytokine and plays an important role in a broad range of biological processes, including cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. To further verify array data, Huh7.5 cells were infected with HCV genotype 2a (clone JFH1) and analyzed for expression of TGF-β isoforms by qRT-PCR using specific primers. TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 mRNA was increased as compared to mock treated control (Fig. 3, panel A), while TGF-β3 expression did not alter (data not shown). Western blot analysis further suggested an increased in TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 expression in HCV infected hepatocytes (Fig. 3, panels B–C). Similar analyses using xenograft tumor lysates were performed for TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 mRNA by qRT-PCR (panel D) and protein analysis by Western blot (panel E). The results showed higher level of TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 in tumor lysates.

Fig. 3. Upregulation of TGF-β in hepatocytes following HCV infection.

RNA from mock or HCV genotype 2a (clone JFH1) infected Huh7.5 cells were analyzed by qRT-PCR using TGF-β isoform specific primers and normalized with 18S RNA (panel A). Results from TGF-β1/β2 expression by Western blot analysis and densitometric scanning results are shown (panels B and C). RNA from xenograft tumor exhibited TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 mRNA expression by qRT-PCR (panel D) and lysates from tumor showed TGF β1/β2 protein expression by Western blot (panel E). β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein control for comparison of protein load in each lane. Values represent mean from three independent experiments ±SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test: *P < 0.05, **P<0.01. The error bar without asterisk represent statistically not significant.

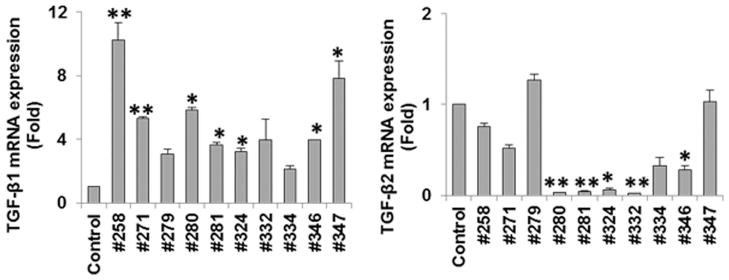

We further examined for TGF-β mRNA expression in chronically HCV infected human liver biopsy specimens by qRT-PCR analysis. Liver biopsy specimens from chronic patients exhibited a significantly higher level of TGF-β1 gene expression as compared to TGF-β2 (Fig. 4). Two human control liver RNAs (C1 and C2) were pooled and used for comparison. The results from these set of experiments suggested that TGF-β1 is primarily upregulated in HCV infected hepatocytes in an in vitro culture and in infected human liver tissues. We had limited liver biopsy specimens, and not enough to stratify with fibrosis stage of the patient sample used, and we did not use HCC liver specimens in this experiment.

Fig. 4. TGF-β1 is up-regulated in chronically HCV infected human liver biopsy specimens.

Expression of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 isoforms were analyzed by qRT-PCR for comparison in chronically HCV infected human liver biopsy specimens. Control human liver RNA from two donors were pooled and included for comparison. Values represent mean from three independent experiments ±SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test: *P < 0.05, **P<0.01. The error bar without asterisk represent statistically not significant.

TGF-β upregulates hepatic stellate cell activation markers and MMP2

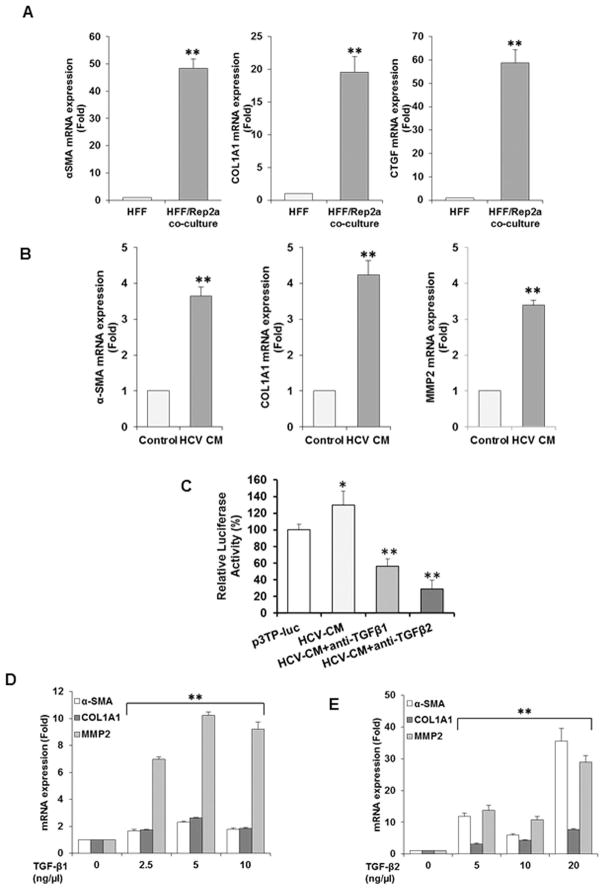

We examined if HCV replicon harboring cells upregulate fibrosis marker genes in fibroblasts. For this, we co-cultured HFF with Huh7.5 cells harboring full-genome length HCV replicon from genotype 2a (Rep2a) for 24h. RNA isolated from cocultured cells were analyzed for fibrosis activation markers. RNA from HFF was used as control. The results suggested an increased mRNA expression level of α-SMA, COL1A1 and CTGF by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5, panel A).

Fig. 5. Upregulation of hepatic stellate cell activation markers (α-SMA/COL1A1) and MMP2 by conditioned medium (CM) from HCV infected hepatocytes.

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts are activated in coculture by HCV replicon harboring hepatocytes. Upregulation of activation markers for HFF (α-SMA/Col1A1/CTGF) in co-culture with HCV 2a replicon were analyzed by qRT-PCR (panel A). mRNA status of activation markers were analyzed by qRT-PCR in LX2 cells upon incubation with CM from HCV infected hepatocytes (panel B). RNA from LX2 incubated with CM from mock infected hepatocytes was used as control. HCV mediated enhancement in TGF-β signaling was analyzed separately in HK293 cells transfected with a TGF-β luciferase reporter (p3TP-luc) construct, containing responsive element with minimal promoter. Cells exposed to conditioned media from HCV infected hepatocytes or neutralized with anti-TGF-β1 or anti-TGF-β2 antibodies (panel C). Luciferase activity was determined 48h post-transfection. Upregulation of activation markers in immortalized hepatic stellate cell (LX2) at mRNA level by TGF-β were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Activation markers (α-SMA/COL1A1) and MMP2 in LX-2 cells were induced at the mRNA level upon treatment with commercially available TGF-β1 (panel D) or TGF-β2 (panel E) at three different doses and analyzed by qRT-PCR. Values represent from three independent experiments ±SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t test: *P < 0.05, **P<0.01.

We used CM from HCV infected hepatoctes to investigate if soluble mediator stimulates fibroblasts. Conditioned medium (CM) from HCV infected hepatocytes was incubated with human hepatic stellate cell line (LX2) and fibrosis markers were examined from RNA of these cells. Our results demonstrated upregulation of α-SMA (>3 fold), COL1A1 (>4 fold) and MMP2 (>3 fold), as compared to CM from mock-infected hepatocytes as control (Fig. 5, panel B). The activity of TGF-β in HCV CM was further examined separately using a functional reporter assay. Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) cells were transfected with a reporter construct p3TP-luc containing three TGF-β response elements with minimal promoter and incubated for 24 h. Cells were incubated with CM from HCV infected hepatocytes or CM incubated with anti-TGF-β1 or anti-TGF-β2 neutralizing antibody. Cells were lysed 48h after transfection and luciferase assay was performed as described previously (21). We observed upregulation of luciferase activity from HCV CM incubation (Fig. 5, panel C), suggesting the presence of TGF-β in CM. HCV CM mediated upregulation was inhibited in presence of TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 neutralizing antibody further suggested the role for the presence of TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 in activation of fibroblast markers. A reduced lucifiease activity from the basal level likely indicates neutralization of endogenous TGF-β in HEK293 cells.

To investigate the role of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 on hepatic stellate cell activation, we used commercially available TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 and incubated with LX2 cells. TGF-β3 was not included in our experiment as it is already known to have a negative effect on TGF-β1 expression and fibrosis inhibitory activity (22, 23). We analyzed for changes in the expression level of known HSC activation markers (α-SMA/COL1A1) and MMP2 genes, as compared to mock-treated negative control. Three different doses of TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 stimulation enhanced the mRNA expression of α-SMA, COL1A1 and MMP2 (Fig. 4, panels D–E). MMPs play central roles in the development of hepatic fibrosis (24), and increasing MMP2 status reflects potential for progressing liver fibrotic and cirrhotic changes in HCV patients (25).

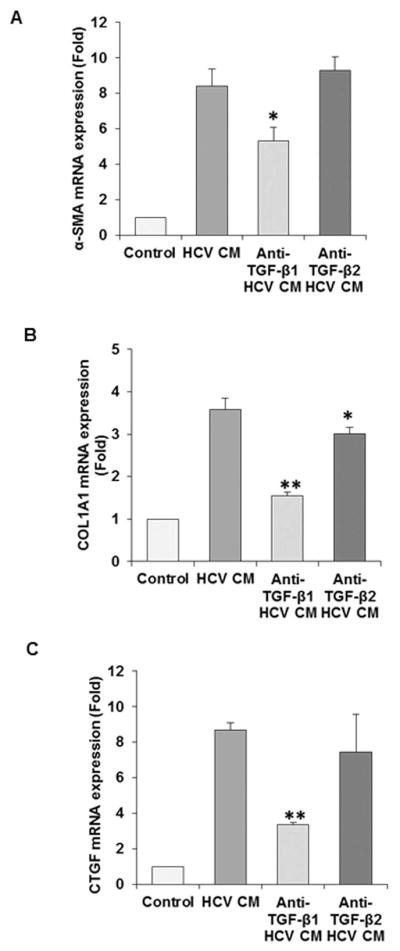

Activation of primary fibroblasts and inhibition by TGF-β1 specific antibody

Since TGF-β is increased upon HCV infection of hepatocytes, we determined whether conditioned medium (CM) from HCV infected hepatocytes activates primary human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) in promoting fibrosis markers, and if anti-TGF-β1 or anti-TGF-β2 neutralizing antibody could inhibit up-regulation of fibrosis markers (α-SMA/Col1A1/CTGF). Our results showed CM from HCV infected hepatocytes activates fibrosis marker genes in primary HSCs which are reduced in the presence of TGF-β1 neutralizing antibody (Fig. 5, panels A–C). On the other hand, TGF-β2 antibody did not display a significant inhibitory activity on these activation markers. These results further suggested the specific role of TGF-β1 in activation of HSCs.

DISCUSSION

Fibrosis and cirrhosis occur in most of the chronically HCV infected patients, although the mechanism for this disease progression is not clearly understood. A number of mechanisms are reported to activate hepatic stellate cells during HCV infection (9, 13, 26). We have recently shown that CCL5 induces in macrophages during exposure to HCV, and miR-19a carried through the exosomes from HCV-infected hepatocytes activate HSC (27, 28). In this study, we demonstrated that HCV infected hepatocytes recruit activated fibroblasts, in part, by secretion of TGF-β. We have previously shown that HCV infection of primary human hepatocytes induces EMT related gene expression and promotes TISC generation (7, 8). TISCs are highly tumorigenic in immunodeficient mice (7). In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that mouse fibroblasts are recruited into xenograft stroma of implanted TISCs into NSG mice. We further showed that HCV infected transformed human heaptocytes secrete TGF-β which induces cellular environment promoting fibroblast activation for stromal changes. TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 are activated and TGF-β3 gene expression is suppressed in HCV infected hepatocytes (8). We analyzed the functional role of TGF-β and appeared to influence as a paracrine response from injected human hepatocytes upon mouse fibroblasts for generation of TAF in the xenograft mouse tumor model. Tumors from implanted TISC of NSG mice exhibited a significantly higher expression level of TAF associated markers (α-SMA and FSP-1). In addition, we observed collagen staining by Sirus Red in TAF, suggesting stromal fibroblast activation in TISC induced tumor microenvironment. We have also demonstrated that TGF-β1 activates primary hepatic stellate cells and TAF markers, and stimulates MMP2 expression in LX2 cells and HFF.

TGF-β1 is activated in HCV infected heaptocytes and may have a role in virus replication (29). Others have shown HCV regulates TGF-β1 production by generation of reactive oxygen species in a NF-κB or miR-192 dependent manner (30, 31, 32). The amino acid sequence of the TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 isoforms are 70–80% similar to each others (33). To make an active protein, a mature TGF-β protein dimerizes (34, 35). TGF-β3 has opposite effect of TGF-β1 in wound heeling (22), and works anti-fibrotic (23). In hepatic stellate cells, TGF-β1 induces Smad2/3 phosphorylation causing stimulation of fibrosis marker (36, 37, 38). TGF-β2 also induces Smad2/3 phosphorylation and causes stimulation of fibrosis marker in eye, bone and heart (39, 40, 41). On the other hand, TGF-β3 block Smad4 through up-regulation of Smad7 phosphorylation (42, 43, 44), which is an inhibitor of TGF-β superfamily signaling (45). There are reports on the differences between TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 in the liver, TGF-β1 induces Smad1 phosphorylation, but TGF-β2 has less affinity for Smad1 phosphorylation (46). We know from our previous results that EMT is induced in HCV infected hepatocytes and generates TGF-β (8). CM from HCV infected hepatocytes promotes human HSCs activation for fibrosis markers. CM from HCV infected hepatocytes contain TGF-β, and inhibition by antibody impair generation of the fibrosis activation markers.

We observed TGF-β stimulates TAF activation markers and MMP2 expression in LX2 cells and primary human foreskin fibroblasts. CM from HCV infected hepatocytes up-regulated fibrosis related markers to a higher magnitude in primary human hepatic stellate cells, as compared to immortalized LX2 cells. Human liver biopsy samples from chronically HCV infected patients exhibited up-regulation of TGF-β1 level, and TGF-β2 was high only in one out of the 10 samples examined in our study. TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 expression were reported higher at the cirrhosis stage than in normal liver (46), but fibrosis stage did not co-relate with TGF-β expression or viral load in our biopsy samples. HCV genotype 3a up-regulated TGF-β1 only in one sample used in our study. These results suggest HCV infected hepatocytes induce liver fibrosis via activation of hepatic stellate cells in a paracrine manner, and significantly influence the network of tumor environment. However, we do not know whether this process in general serves to support outgrowth of non-TISC tumors. Interestingly, TGF-β is markedly up-regulated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) (47). Cancer cells and normal fibroblasts contribute to the emergence of TAFs through TGF-β and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (48). On the other hand, the enhanced bone resorption in multiple myeloma bone lesions causes a marked increase in the release and activation of TGF-β (49). Thus, TGF-β may support non-TISC tumor growth, and not specific to HCC, by influencing the secretion of other growth factors and manipulation of the tumor microenvironment.

In summary, we demonstrated that HCV induced TISCs promote cancer associated fibroblast activation markers and CM from HCV induced TISCs indeed activates fibrosis markers via TGF-β and is reduced following neutralization by specific antibody. These results suggest HCV infected hepatocytes induce liver fibrosis via activation of hepatic stellate cells by TGF-β, and preneoplastic or tumor state of the hepatocytes influence the network for TAF environment.

Fig. 6. Activation of primary fibroblasts by HCV and inhibition by antibody to TGF-β1.

Activation of fibroblast activation markers are primarily inhibted by TGF-β1 specific antibody in primary human hepatic stellate cells (panels A–C). Upregulated activation markers for primary human HSC (α-SMA/Col1A1/CTGF) with conditioned medium (CM) from HCV infected immortalized human hepatocyte are neutralized in presence of TGF-β specific antibodies. Activation markers were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Values represent from three independent experiments ±SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test: *P < 0.05, **P<0.01.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants DK081817(RBR) and DK113645 (RR)f rom the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Adrian M. Di Bisceglie for providing coded archieved liver biopsy specimens for the study.

References

- 1.Banerjee A, Ray RB, Ray R. Oncogenic potential of hepatitis C virus proteins. Viruses. 2010;2:2108–33. doi: 10.3390/v2092108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–1273. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arzumanyan A, Reis HMGPV, Feitelson MA. Pathogenic mechanisms in HBV- and HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:123–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour J-F, Lammert F, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308:2584–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.144878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conti F, Buonfiglioli F, Scuteri A, Crespi C, Bolondi L, Caraceni P, et al. Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol. 2016;65:727–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reig M, Mariño Z, Perelló C, Iñarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A, Lens S, et al. Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol. 2016;65:719–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon Y-C, Bose SK, Steele R, Meyer K, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray RB, et al. Promotion of Cancer Stem-Like Cell Properties in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Hepatocytes. J Virol. 2015;89:11549–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01946-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bose SK, Meyer K, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray RB, Ray R. Hepatitis C Virus Induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Primary Human Hepatocytes. J Virol. 2012;86:13621–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02016-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwakiri Y, Shah V, Rockey DC. Vascular pathobiology in chronic liver disease and cirrhosis - current status and future directions. J Hepatol. 2014;61:912–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song J, Ge Z, Yang X, Luo Q, Wang C, You H, et al. Hepatic stellate cells activated by acidic tumor microenvironment promote the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via osteopontin. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:713–20. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang J-W, Yoon S-J, Sung Y-K, Lee S-M. Magnesium chenoursodeoxycholic acid ameliorates carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012;237:83–92. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang DY, Friedman SL. Fibrosis-dependent mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2012;56:769–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.25670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang N, Gores GJ, Shah VH. Hepatic stellate cells: partners in crime for liver metastases? Hepatology. 2011;54:707–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.24384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamura T, Morita K, Iwasaki Y, Inoue M, Komai T, Fujio K, et al. Role of TGF-β3 in the regulation of immune responses. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujio K, Komai T, Inoue M, Morita K, Okamura T, Yamamoto K. Revisiting the regulatory roles of the TGF-β family of cytokines. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:917–22. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saha B, Kodys K, Szabo G. Hepatitis C Virus-Induced Monocyte Differentiation Into Polarized M2 Macrophages Promotes Stellate Cell Activation via TGF-β. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2(3):302–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soldano S, Pizzorni C, Paolino S, Trombetta AC, Montagna P, Brizzolara R, et al. Alternatively Activated (M2) Macrophage Phenotype Is Inducible by Endothelin-1 in Cultured Human Macrophages. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray RB, Meyer K, Ray R. Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein Promotes Immortalization of Primary Human Hepatocytes. Virology. 2000;271:197–204. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L, Hui AY, Albanis E, Arthur MJ, O’Byrne SM, Blaner WS, et al. Human hepatic stellate cell lines, LX-1 and LX-2: new tools for analysis of hepatic fibrosis. Gut. 2005;54:142–51. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goutté N, Sogni P, Bendersky N, Barbare JC, Falissard B, Farges O. Geographical variations in incidence, management and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in a Western country. J Hepatol. 2017;66:537–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazumdar B, Kim H, Meyer K, Bose SK, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray RB, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection upregulates CD55 expression on the hepatocyte surface and promotes association with virus particles. J Virol. 2013;87:7902–10. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00917-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujio K, Komai T, Inoue M, Morita K, Okamura T, Yamamoto K. Revisiting the regulatory roles of the TGF-β family of cytokines. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:917–22. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ask K, Bonniaud P, Maass K, Eickelberg O, Margetts PJ, Warburton D, et al. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis is mediated by TGF-beta isoform 1 but not TGF-beta3. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:484–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benyon RC, Arthur MJ. Extracellular matrix degradation and the role of hepatic stellate cells. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:373–84. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurzepa J, Mądro A, Czechowska G, Kurzepa J, Celiński K, Kazmierak W, et al. Role of MMP-2 and MMP-9 and their natural inhibitors in liver fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis and non-specific inflammatory bowel diseases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014;13:570–9. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(14)60261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitano Mio, Mark Bloomston P. Hepatic Stellate Cells and microRNAs in Pathogenesis of Liver Fibrosis. J Clin Med. 2016;5:38. doi: 10.3390/jcm5030038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki R, Devhare PB, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus induced CCL5 secretion from macrophages activates hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/hep.29170. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devhare PB, Sasaki R, Shrivastava S, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray R, Ray RB. Exosome-Mediated Intercellular Communication between Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Hepatocytes and Hepatic Stellate Cells. J Virol. 2017;91:e02225–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02225-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Presser LD, Haskett A, Waris G. Hepatitis C virus-induced furin and thrombospondin-1 activate TGF-β1: role of TGF-β1 in HCV replication. Virology. 2011;412:284–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin W, Tsai W-L, Shao R-X, Wu G, Peng LF, Barlow LL, et al. Hepatitis C virus regulates transforming growth factor beta1 production through the generation of reactive oxygen species in a nuclear factor kappaB-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2509–18. 2518. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luedde T, Schwabe RF. NF-κB in the liver--linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:108–18. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JH, Lee CH, Lee S-W. Hepatitis C virus infection stimulates transforming growth factor-β1 expression through up-regulating miR-192. J Microbiol. 2016;54:520–6. doi: 10.1007/s12275-016-6240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derynck R, Lindquist PB, Lee A, Wen D, Tamm J, Graycar JL, et al. A new type of transforming growth factor-beta, TGF-beta 3. EMBO J. 1988;7:3737–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herpin A, Lelong C, Favrel P. Transforming growth factor-beta-related proteins: an ancestral and widespread superfamily of cytokines in metazoans. Dev Comp Immunol. 2004;28:461–85. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daopin S, Piez KA, Ogawa Y, Davies DR. Crystal structure of transforming growth factor-beta 2: an unusual fold for the superfamily. Science. 1992;257:369–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1631557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan X, Zhang Q, Li S, Lv Y, Su H, Jiang H, et al. Attenuation of CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis in mice by vaccinating against TGF-β1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li T, Longobardi L, Myers TJ, Temple JD, Chandler RL, Ozkan H, et al. Joint TGF-β type II receptor-expressing cells: ontogeny and characterization as joint progenitors. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1342–59. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y, Tong X, Ren S, Wang X, Chen J, Mu Y, et al. Synergistic anti-liver fibrosis actions of total astragalus saponins and glycyrrhizic acid via TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathway modulation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;190:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma B, Kang Q, Qin L, Cui L, Pei C. TGF-β2 induces transdifferentiation and fibrosis in human lens epithelial cells via regulating gremlin and CTGF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;447:689–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wordinger RJ, Sharma T, Clark AF. The Role of TGF-β2 and Bone Morphogenetic Proteins in the Trabecular Meshwork and Glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2014;30:154–62. doi: 10.1089/jop.2013.0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talior-Volodarsky I, Arora PD, Wang Y, Zeltz C, Connelly KA, Gullberg D, et al. Glycated Collagen Induces α11 Integrin Expression Through TGF-β2 and Smad3. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:327–36. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Qi J, Tao Y, Zhang H, Yin J, Ji M, et al. Correlation of proliferation, TGF-β3 promoter methylation, and Smad signaling in MEPM cells during the development of ATRA-induced cleft palate. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;61:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang K, Chun G, Wang Z, Du Q, Wang A, Xiong Y. Effect of transforming growth factor-β3 on the expression of Smad3 and Smad7 in tenocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:3567–73. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo X, Hutcheon AEK, Zieske JD. Molecular insights on the effect of TGF-β1/-β3 in human corneal fibroblasts. Exp Eye Res. 2016;146:233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penn JW, Grobbelaar AO, Rolfe KJ. The role of the TGF-β family in wound healing, burns and scarring: a review. Int J Burns Trauma. 2012;2:18–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dropmann A, Dediulia T, Breitkopf-Heinlein K, Korhonen H, Janicot M, Weber SN, et al. TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 abundance in liver diseases of mice and men. Oncotarget. 2016;7:19499–518. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friess H, Yamanaka Y, Büchler M, Ebert M, Beger HG, Gold LI, et al. Enhanced expression of transforming growth factor beta isoforms in pancreatic cancer correlates with decreased survival. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1846–56. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91084-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan B, Liao Q, Niu Z, Zhou L, Zhao Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Futur Oncol. 2015;11:2603–2610. doi: 10.2217/FON.15.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsumoto T, Abe M. TGF-β-related mechanisms of bone destruction in multiple myeloma. Bone. 2011;48:129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]