Abstract

The incidence of depression is approximately 2-fold greater in women than men but the biological mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain unclear. One potential mechanism that has been understudied is immune function, which is modulated by sex hormones and differs considerably between males and females. The immune-regulating kynurenine pathway previously has been implicated in the pathogenesis of mood disorders. In particular, a decreased ratio of neuroprotective (kynurenic acid; KynA) to neurotoxic (3-hydroxykynurenine; 3HK and quinolinic acid; QA) kynurenine pathway metabolites has been reported in several mood disorder subtypes. Yet there is a paucity of research investigating sex differences in the kynurenine pathway in the context of depression. Similarly, oral contraceptive (OC) use has been shown to be a risk factor for depression but to our knowledge this epidemiological relationship has not been considered within the framework of immune dysfunction. Here, we compared the concentrations of c-reactive protein (CRP) and kynurenine pathway metabolites in a combined sample of subjects with major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder (BD), and healthy controls (HC) comprising 130 men and 350 women. CRP was measured in a CLIA-certified hospital laboratory. Kynurenine metabolites were quantified using high performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Estradiol and progesterone were quantified with the Mesoscale Discovery (MSD) platform. After controlling for diagnosis, age, sex, BMI, analysis batch, and self-reported childhood trauma we found that women had significantly lower KynA/3HK and KynA/QA ratios than men, and that these results were driven by a decrease in KynA. There was no significant difference between males and females in the concentration of CRP. Further, women taking OC showed significantly higher levels of CRP and lower ratios of KynA/3HK and KynA/QA compared with women on no form of contraception. Moreover, among women using OC, progesterone concentrations were positively correlated with KynA, KynA/3HK, and KynA/QA. Although preliminary, our results indicate that on average, healthy women show the same pattern of kynurenine pathway metabolism as that observed in subjects with depression. This finding raises the possibility that a reduction in KynA concentrations in women may constitute a vulnerability factor that partly explains the higher incidence of depression in females. Further, the significant association between OC use and reduced KynA as well as increased CRP, could conceivably partially account for the epidemiological association between OC use and depression. Nonetheless, because of the cross-sectional nature of this study, these hypotheses need to be more rigorously tested with longitudinal designs and/or large epidemiological studies.

Keywords: Depression, Sex Differences, Kynurenine Pathway, Inflammation, Oral Contraceptives, Kynurenic Acid, Estradiol, Progesterone, C-reactive protein, Bipolar Disorder

Introduction

The lifetime rate of major depressive disorder (MDD) in women consistently has been found to be twice that of men (Kessler, 2003) but the biological mechanisms underlying this epidemiological phenomenon remain unclear. Most research has focused on hormonal differences, yet it is clear that there are significant differences in immune function between the sexes. For instance, females show greater expression of toll-like receptors (TLR) across multiple populations of immune cells, increased type-1 interferon activity of dendritic cells, increased activation and function of macrophages, neutrophils, and T-cells, as well as greater B-cell numbers and antibody production (Klein and Flanagan, 2016). Consistent with these data, females mount a stronger immune response to infection and vaccines, and are significantly more likely than males to suffer from inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (Klein and Flanagan, 2016). Given evidence that immune dysregulation plays a mechanistic role in some depressive disorders (Mechawar and Savitz, 2016; Miller and Raison, 2015), it is conceivable that sex differences in the incidence of depression may partly be related to immunological differences between males and females. Yet there is paucity of research addressing this important topic.

The mechanisms by which inflammatory mediators putatively contribute to the pathophysiology of depression remain unclear. However, activation of a key immuno-regulatory network, the kynurenine pathway, appears to be crucial. Two landmark papers showed that lipopolysaccharide does not cause depression-like behavior in rodents when the activation of the kynurenine pathway is genetically or pharmacologically blocked even when the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines remain elevated (Lawson et al., 2013; O'Connor et al., 2009). The kynurenine pathway is activated by inflammatory cytokines (predominantly interferon gamma) and cortisol, increasing the production of kynurenine from tryptophan (TRP) by the enzymes IDO and TDO, respectively (Figure S1). Kynurenine is in turn metabolized into either the putatively neuroprotective metabolite kynurenic acid (KynA), by astrocytes, or alternatively, putative neurotoxic metabolites such as 3-hydroxykynurenine (3HK) and quinolinic acid (QA) by macrophages and microglia. Under inflammatory conditions, the brain formation of QA predominates over the formation of KynA (Saito et al., 1992; Walker et al., 2013), such that the ratio of KynA/3HK and KynA/QA provides an index of the competing physiological effects of these neuroactive metabolites. We and others have previously reported reduced levels of KynA/3HK and/or KynA/QA in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid of several different mood disorder subtypes relative to controls (Bay-Richter et al., 2015; Myint et al., 2007; Poletti et al., 2016; Savitz et al., 2015a; Savitz et al., 2015b; Savitz et al., 2015c; Schwieler et al., 2016). Here, we combine these existing data with a new dataset (total n=480) in order to perform a well-powered test of our hypothesis that, compared with males, females will have higher levels of inflammation (indexed by C- reactive protein (CRP)) and will show a greater metabolic shunt towards the neurotoxic branch of the kynurenine pathway. Given the recent report of an epidemiological relationship between depression and oral contraceptive (OC) use (Skovlund et al., 2016), we also hypothesized that serum concentrations of CRP and potentially neurotoxic metabolites would be elevated in females taking OC.

Methods

The current research was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. A total of 480 participants (130 men and 350 women) were included in the study (Table 1). Data from a subset of these participants (n=345) has been previously published although the hypotheses tested herein were not also tested in these publications (Savitz et al., 2015a; Savitz et al., 2015b; Savitz et al., 2015c; Young et al., 2016). The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR was used to confirm the diagnoses rendered by a clinical interview with a psychiatrist. Participants met DSM-IV-TR criteria for remitted major depressive disorder (rMDD), current major depressive disorder (dMDD), bipolar disorder (BD) or no psychiatric disorder (i.e., healthy controls (HC)) (Table 1). Exclusion criteria included serious suicidal ideation or behavior, medical conditions or concomitant medications likely to influence central nervous system or immunological function including cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, neurological, and known autoimmune disease, as well as a history of drug or alcohol abuse within six months or a history of drug or alcohol dependence within one year. The subjects with a mood disorder were unmedicated for at least 2 weeks (8 weeks for fluoxetine, mean time unmedicated: 3.52 years ± 3.09 years) except for a subset of the MDD and BD samples (n=60) who were receiving treatment with psychotropic medications at the time of study (Table S1). We previously reported that unmedicated and medicated BD subjects did not differ significantly in KynA/3HK or KynA/QA (Savitz et al., 2015a). Self-reported trauma was measured with the 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein et al., 2003). The CTQ is composed of the following Likert-type subscales: physical, sexual and emotional abuse and physical and emotional neglect. Higher scores are indicative of greater self-reported trauma. The instrument is widely used, reliable (intra-class correlation coefficients of 0.88; Cronbach’s alpha, 0.79–0.94), and well validated with correlations with therapist ratings of abuse for all the CTQ subscales of between 0.36 and 0.75 (Bernstein et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Kynurenine Pathway Differences Between Men and Women and the Effects of Oral Contraceptives.

| Demographics | Men | Women | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | 130 | 350 | |

| Age | 34.2±11.3 | 34.7±11.1 | t(478)=0.45, p=0.65 |

| BMI | 27.1±5.01 | 28.0±6.58 | t(478)=1.44, p=0.15 |

| CRP N available | 66 | 159 | |

| Hormone N available | 0 | 277 | |

| CTQ N available | 83 | 232 | |

| CTQ total score** | 36.9±14.21 | 47.0±20.73 | t(313)=4.12, p<0.001 |

| Diagnosis N (% total)* | Χ2(3)=10.0, p=0.018 | ||

| HC | 72 (55%) | 147 (42%) | |

| rMDD | 14 (11%) | 28 (8%) | |

| dMDD | 31 (24%) | 120 (34%) | |

| BD | 13 (10%) | 55 (16%) | |

| Oral Contraceptive Use N (% total) | |||

| None | - | 203 (58%) | |

| Oral | - | 42 (12%) | |

| Other/Unknown | - | 105 (30%) | |

| Hysterectomy+ N | - | 40 | |

| Menstrual Phase | |||

| Follicular | 14 | ||

| Luteal | 26 | ||

| Not Available/Irregular Cycle | 310 | ||

| Sex Effects | |||

| A priori comparisons | Men | Women | Statistic |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.35±3.12 | 3.42±4.67 | F(1,218)=0.13, p=0.72, d=0.054 |

| KynA/3HK** | 1.58±0.44 | 1.18±0.41 | F(1,464)=76.9, p<0.001, d=0.914 |

| KynA/QA** | 0.15±0.06 | 0.11±0.04 | F(1,464)=48.4, p<0.001, d=0.728 |

| Secondary comparisons | Men | Women | Statistic |

| Kyn/TRP | 0.03±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 | F(1,470)=0.08, p=0.772, d=0.048 |

| KynA (nM)** | 48.7±16.6 | 35.2±13.2 | F(1,464)=84.7, p<0.001, d=0.962 |

| 3HK (nM) | 32.1±12.6 | 31.3±11.0 | F(1,470)=0.72, p=0.40, d=0.089 |

| QA (nM)* | 355±127 | 330±114 | F(1,470)=6.45, p=0.011, d=0.264 |

| Kyn (µM)** | 2.07±0.47 | 1.79±0.43 | F(1,470)=42.1, p<0.001, d=0.671 |

| TRP (µM)** | 66.6±14.7 | 57.2±11.3 | F(1,470)=54.8, p<0.001, d=0.769 |

| OC Effects | |||

| A priori comparisons | No BC | OC | Statistic |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.90±4.67 | 4.12±4.03 | F(1,108)=20.3, p<0.001, d=1.07 |

| KynA/3HK** | 1.21±0.40 | 1.00±0.32 | F(1,230)=10.8, p=0.001, d=0.583 |

| KynA/QA** | 0.12±0.04 | 0.10±0.04 | F(1,230)=13.2, p<0.001, d=0.642 |

| Secondary comparisons | No BC | OC | Statistic |

| Kyn/TRP | 0.03±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 | F(1,235)=1.63, p=0.202, d=0.226 |

| KynA (nM)* | 36.7±14.7 | 29.7±9.17 | F(1,230)=5.91, p=0.016, d=0.431 |

| 3HK (nM) | 31.5±10.4 | 31.2±9.1 | F(1,235)=1.12, p=0.290, d=0.189 |

| QA (nM) | 325±104 | 328±88.5 | F(1, 235)=1.78, p=0.180, d=0.234 |

| Kyn (µM) | 1.82±0.44 | 1.71±0.35 | F(1, 235)=0.48, p=0.487, d=0.124 |

| TRP (µM) | 57.0±11.7 | 60.5±12.3 | F(1, 235)=0.47, p=0.493, d=0.120 |

| Estradiol (ng/mL)* | 0.17±0.19 | 0.11±0.13 | F(1, 186)=8.64, p=0.004, d=0.558 |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) | 1.48±1.80 | 1.08±0.83 | F(1, 181)=0.56, p=0.457, d=0.142 |

| Phase Effects | |||

| A priori comparisons | Follicular | Luteal | Statistic |

| CRP (mg/L) | 6.62±10.9 | 2.89±4.81 | F(1,16)=1.00, p=0.333, d=0.459 |

| KynA/3HK | 1.22±0.35 | 1.28±0.35 | F(1,29)=0.17, p=0.686, d=0.152 |

| KynA/QA | 0.13±0.05 | 0.13±0.04 | F(1,29)=0.67, p=0.421, d=0.302 |

| Secondary comparisons | Follicular | Luteal | Statistic |

| Kyn/TRP | 0.03±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 | F(1,30)=0.23, p=0.635, d=0.177 |

| KynA (nM) | 34.1±12.4 | 41.5±11.3 | F(1,29)=2.36, p=0.136, d=0.573 |

| 3HK (nM) | 28.3±6.64 | 34.4±11.5 | F(1,30)=2.03, p=0.164, d=0.529 |

| QA (nM) | 290±93.4 | 342±120 | F(1,30)=0.70, p=0.409, d=0.312 |

| Kyn (µM) | 1.72±0.25 | 1.86±0.42 | F(1,30)=0.78, p=0.384, d=0.331 |

| TRP (µM) | 58.0±9.52 | 58.5±11.2 | F(1,30)=0.14, p=0.713, d=0.138 |

| Estradiol (ng/mL) | 0.24±0.20 | 0.22±0.32 | F(1,26)=0.02, p=0.898, d=0.048 |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) | 2.30±3.00 | 2.54±2.83 | F(1,25)=0.00, p=0.998, d=0.00 |

Raw mean values of kynurenine pathway metabolites and C-reactive protein (CRP) are shown, along with standard deviations. Statistics are performed on natural log-transformed data. Effect sizes (d) for contrasts of interest were calculated as the difference in adjusted means divided by the root mean square error.

indicates < 0.05,

indicates ≤0.001, uncorrected.

BMI=body mass index, CTQ=childhood trauma questionnaire, HC=healthy control, rMDD=remitted major depressive disorder, dMDD= diagnosed major depressive disorder, BD=bipolar disorder, Kyn-kynurenine, TRP=tryptophan, KynA=kynurenic acid, 3HK=3-hydroxykynurenine, QA=quinolinic acid, BC=birth control, OC= oral contraceptive,.

An overnight fasting blood sample was collected via venipuncture using Becton Dickinson (BD) Vacutainer serum tubes between 8am and 11am, processed per standard protocol and stored at - 80°C. hs-CRP was measured in a CLIA-certified hospital lab (measurement range of 0.2 mg/L to 480.0 mg/L). Tryptophan (TRP) and kynurenine metabolites including kynurenic acid (KynA), 3-hydroxykynurenine (3HK), and quinolinic acid (QA) were measured blind to sex and diagnostic status by Brains Online, LLC using high performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. This assay had the following lower level of quantifications (LLOQ): TRP=5 µM, Kyn=0.50 µM, KynA=7.5 nM, 3HK=5 nM, and QA=100 nM. Six participants (5 women) had KynA levels below the LLOQ and were excluded from further analysis. Estradiol (LLOQ=0.005ng/mL; CV=7.01%) and Progesterone (LLOQ=0.17ng/mL; CV=9.42%) were quantified blind to sex and diagnostic status using the Mesoscale Discovery MULTI-SPOT® 96 HB 4-Spot Custom Steroid Hormone Panel. Samples with estradiol (n=9) or progesterone (n=13) concentrations with a CV>25% were excluded from the analyses.

Menstrual cycle was evaluated by self-report based on the first day of the last menstrual period. Naturally-cycling females were divided into two groups, follicular phase (days 0–14; low progesterone) or luteal phase (days 15–30; high estrogen/progesterone). Women on birth control or with irregular cycles (defined as shorter than 21 days or longer than 36 days, n=36) were excluded. Phase information was only available for a subset of women (Table 1).

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 21). Sex differences in age, body mass index (BMI), self-reported childhood trauma, and diagnosis were assessed using independent samples t-tests and chi-squared tests. Shapiro-Wilk tests showed that kynurenine metabolites hormone levels, and CRP were non-normally distributed (p<0.05), and thus these variables were natural log transformed.

The effects of sex on the a priori outcome variables KynA/QA, KynA/3HK, and CRP were assessed using an additive general linear model to control for analysis batch, BMI, age, and diagnosis. These covariates were selected a priori rather than empirically (i.e. age and BMI were modeled even though they did not differ between males and females). Because self-reported trauma scores were not available for all individuals, we also ran a second model with CTQ score included as an additional covariate. Females generally report higher levels of early trauma, which has in turn been associated with higher levels of inflammation in adolescence (Miller and Chen, 2010). With the exception of the CTQ score, the same covariates were used in the comparison of females with OC use to females (both randomly cycling and non-cycling women) on no hormonal contraception. The same covariates were used in the comparisons testing the effect of menstrual phase. These analyses included estradiol and progesterone in addition to KynA/QA, KynA/3HK, and CRP.

Results

Consistent with the literature, women were over-represented in the mood disorder groups and reported higher levels of childhood trauma than men (full stats are reported in Table 1). In the full sample, CRP was positively correlated with Kyn/TRP (r=0.22, p=0.001) and inversely correlated with KynA/3HK (r=-0.16, p=0.02), and KynA/QA (r=-0.12, p=0.08). KynA/3HK and KynA/QA were positively correlated (r=0.63, p<0.001), while Kyn/TRP was inversely correlated with KynA/3HK (r=- 0.10, p=0.02) and KynA/QA (r=-0.12, p=0.009). In the full sample of women, estradiol was positively correlated with progesterone (r=0.44, p<0.001). Neither estradiol nor progesterone correlated with CRP, KynA/3HK, KynA/QA, or Kyn/TRP (|r|<0.10, p>0.10).

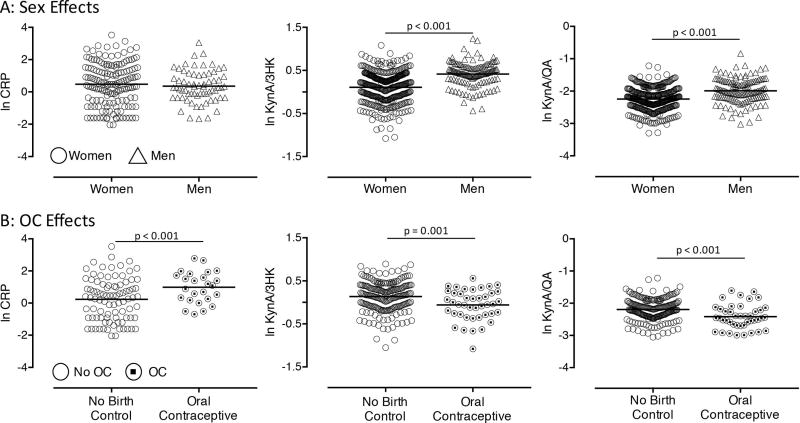

After controlling for batch, BMI, age, and diagnosis, there was no sex difference in CRP levels (p=0.72). However, the effect of sex on KynA/3HK (p<0.001) as well as KynA/QA (p<0.001) was significant, with women showing significantly lower ratios than men across both the healthy and depressed subgroups (Figure 1A, Figure S2). The results remained significant after additionally controlling for CTQ scores - KynA/3HK (p<0.001), and KynA/QA (p<0.001). Secondary analyses found that sex differences in KynA/3HK and KynA/QA were driven by lower KynA in women (Table 1). Women also had significantly lower levels of QA than men, although the levels of 3HK did not differ between men and women.

Figure 1. Sex differences in a priori measures of inflammation and the kynurenine pathway.

Scatter plots show natural log transformed (ln) levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), the ratio of kynurenic acid to 3-hydroxykynurenine (KynA/3HK), and the ratio of kynurenic acid to quinolinic acid (KynA/QA) broken down by sex (A) and oral contraceptive use (B). Horizontal line represents the group mean.

Women taking OC had significantly lower levels of estradiol compared to women on no form of hormonal contraception (p=0.004), while progesterone levels did not differ between groups. Women taking OC had elevated CRP levels relative to those on no form of hormonal contraception (p<0.001). There also was a significant effect of OC use on KynA/3HK (p=0.001) and KynA/QA (p<0.001), with women on OC having lower ratios of KynA/QA and KynA/3HK (Figure 1B). Secondary analyses showed that women on OC had lower KynA, while there were no differences in 3HK or QA (Table 1). Further, in women taking OC, progesterone was positively correlated with KynA/3HK (r=0.34, p=0.037), KynA/QA (r=0.33, p=0.040), and KynA (r=0.46, p=0.003).

Due to the effects of OC on KynA/3HK and KynA/QA, additional analyses were conducted to determine whether women not on OC had lower ratios relative to men. Consistent with the primary analyses, women not on OC had lower KynA/3HK (p<0.001) and KynA/QA (p<0.001) relative to men.

Regarding menstrual phase, CRP, KynA/3HK, KynA/QA, progesterone, and estradiol did not differ between naturally-cycling females in the follicular versus luteal phase (p’s>0.10; Table 1).

Discussion

Our two main findings are firstly, a diagnosis-independent reduction in KynA, KynA/3HK, and KynA/QA in females versus males, and secondly, an increase in CRP along with a greater reduction in KynA, KynA/3HK, and KynA/QA in females on OC versus females not on any form of hormonal birth control. These results are not only highly significant (p’s<0.001) but have large effect sizes (ηp2≤0.15, d≤1.07) in the context of psychiatric research, and are likely to be highly robust considering the size of the sample.

The biological mechanism underlying these sex and OC effects is unclear but one possibility is the presence of a significant interaction between sex hormones and the immune system. Estrogen receptors are expressed on lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, and many genes of the innate immune system contain estrogen response elements (Hewagama et al., 2009). The interaction between sex hormones and the immune system is highly complex since the effect of the hormones appears to be immune cell-specific as well as context and dose-dependent (Klein and Flanagan, 2016; Kovats, 2015). Testosterone and progesterone are generally considered to be anti-inflammatory. In contrast, low concentrations of estradiol can be pro-inflammatory while high concentrations of estradiol may be anti-inflammatory (Klein and Flanagan, 2016), possibly explaining why estrogen and estrogenic medications have been reported to counteract brain inflammation by targeting the production and release of inflammatory mediators from glial cells (Arevalo et al., 2012). Thus, the increased concentration of CRP in OC users versus women on no form of hormonal contraception potentially is consistent with the estrogen-lowering effects of certain OCs. Regarding the kynurenine pathway, treatment of rhesus monkeys with estradiol (or estradiol plus progesterone) was found to result in a significant reduction in the expression of kynurenine mono-oxygenase (KMO) in the raphe (Reddy and Bethea, 2005). KMO is the enzyme that converts kynurenine to 3HK. Thus, this potentially protective effect of (higher levels of) estradiol (Figure S1) is consistent with our finding of an increase in 3HK/KynA in OC users, since on average, this group had lower plasma concentrations of estradiol than non-OC users. Similar results to ours were also recently reported in a nutritional study of young healthy participants with lower KynA in women versus men (28%) and in OC users versus non-OC users (19%) (Deac et al., 2015).

The fact that within the OC group, progesterone was positively correlated with KynA, KynA/3HK, and KynA/QA potentially is consistent with a recent in vitro study that demonstrated that treatment of human macrophages with progesterone attenuated interferon gamma-induced activation of the kynurenine pathway, decreased QA, and increased KynA concentrations (de Bie et al., 2016). Since significant correlations between progesterone and KynA, KynA/3HK, and KynA/QA were not observed in the non-OC group, it is conceivable that the effects of progesterone on the kynurenine pathway may be more salient in the context of reduced estradiol concentrations. Whether progestin- only medications exert a differential effect on kynurenine metabolism compared with combined estradiol and progestin medications is unclear. Because this study was not primarily designed to test for sex differences and the effects of hormones on kynurenine metabolites, we did not have the statistical power to differentiate between different classes of OC or to control for length of time on OC. Parenthetically, in the Skovlund et al. analysis, the association between depression and OC use held for both combined and progestin-only products (Skovlund et al., 2016). Regarding other limitations, the results of the menstrual phase analysis should be treated with caution because the small sample size may have resulted in false negative results. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the design does not allow us to test whether OC hormone levels cause changes in the kynurenine pathway.

Although the CRP concentrations did not differ significantly between men and women in our study, this may reflect Type II error since other studies have reported higher levels of CRP in females (Hutchinson et al., 2000; Sorensen et al., 2014), and in our sample the mean CRP levels were 46% higher in women than in men, but the difference was not significant because of the relatively high variability in these values in both sexes (the coefficients of variance were 133% and 137% in the men and women, respectively). Nevertheless, there also are several well-powered negative reports in the literature (Chenillot et al., 2000; Rifai and Ridker, 2003). The association between CRP and OC use in females is consistent with a recent epidemiological analysis demonstrating that OC use is the strongest predictor of inflammation, indexed by CRP, in pre-menopausal women (Sorensen et al., 2014). These data echo the results of earlier studies reporting that the plasma levels of CRP in OC users were three times higher than in non-OC users (Frohlich et al., 1999), and that OC use explained 32% of the variance in CRP concentrations in young, healthy women (Dreon et al., 2003)

In sum, there are a handful of papers (Deac et al., 2015; Dreon et al., 2003; Rifai and Ridker, 2003; Sorensen et al., 2014) that have examined sex differences and the effects of OC on inflammatory mediators in humans. These studies have been performed in the context of cardiovascular disease or nutritional research. In contrast, the implications of these sex and OC effects for mood disorders has not been explicitly addressed. Here we show that females, irrespective of diagnosis, show a metabolic shunt towards the neurotoxic branch of the kynurenine pathway that is driven by a decrease in levels of the neuroprotective metabolite, KynA. The fact that, on average, healthy females show the same pattern (but not necessarily the same magnitude) of change as individuals with mood disorders raises the possibility that a reduction in the neuroprotective arm of the kynurenine pathway in females may constitute a vulnerability factor that partly explains the higher incidence of depression in females. Secondly, the association between OC use and reduced KynA as well as increased CRP, conceivably may partially account for the epidemiological association between OC use and depression. Nevertheless, while these results constitute important new leads, they require confirmation and characterization in studies employing prospective, longitudinal designs and in large-scale epidemiological studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Women have reduced levels of protective vs. toxic kynurenine metabolites than men

This diagnosis-independent effect is driven by a decrease in kynurenic acid (KynA)

Women using oral contraceptives (OC) have higher CRP levels than women not using OC

Women using OC have lower KynA concentrations than women not using OC

Women may be more vulnerable to depression due to a hormonal-immune interaction

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research participants and wish to acknowledge the contributions of Brenda Davis, Debbie Neal, Chibing Tan, and Ashlee Taylor from the laboratory of TKT at the University of Oklahoma Integrative Immunology Center who played invaluable roles in transporting and processing the blood samples.

Financial Disclosures

This study was partly funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to JS (K01MH096077). JB and JS also receive support from the William K. Warren Foundation. TM received support for this work through a project funded through the Research and Education Program, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin. RD is supported by NIH R21MH104694 and R01CA193522. Wayne Drevets, M.D. is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals of Johnson & Johnson, Inc., Titusville, NJ, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The other authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- Arevalo MA, Diz-Chaves Y, Santos-Galindo M, Bellini MJ, Garcia-Segura LM. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators decrease the inflammatory response of glial cells. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Richter C, Linderholm KR, Lim CK, Samuelsson M, Traskman-Bendz L, Guillemin GJ, Erhardt S, Brundin L. A role for inflammatory metabolites as modulators of the glutamate N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in depression and suicidality. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;43:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenillot O, Henny J, Steinmetz J, Herbeth B, Wagner C, Siest G. High sensitivity C-reactive protein: biological variations and reference limits. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2000;38:1003–1011. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2000.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bie J, Lim CK, Guillemin GJ. Progesterone Alters Kynurenine Pathway Activation in IFN-gamma-Activated Macrophages - Relevance for Neuroinflammatory Diseases. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2016;9:89–93. doi: 10.4137/IJTR.S40332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deac OM, Mills JL, Shane B, Midttun O, Ueland PM, Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME, Laird E, Gibney ER, Fan R, Wang Y, Brody LC, Molloy AM. Tryptophan catabolism and vitamin B-6 status are affected by gender and lifestyle factors in healthy young adults. J Nutr. 2015;145:701–707. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.203091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreon DM, Slavin JL, Phinney SD. Oral contraceptive use and increased plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. Life Sci. 2003;73:1245–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich M, Doring A, Imhof A, Hutchinson WL, Pepys MB, Koenig W. Oral contraceptive use is associated with a systemic acute phase response. Fibrinolysis and Proteolysis. 1999;13:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Hewagama A, Patel D, Yarlagadda S, Strickland FM, Richardson BC. Stronger inflammatory/cytotoxic T-cell response in women identified by microarray analysis. Genes Immun. 2009;10:509–516. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson WL, Koenig W, Frohlich M, Sund M, Lowe GD, Pepys MB. Immunoradiometric assay of circulating C-reactive protein: age-related values in the adult general population. Clin Chem. 2000;46:934–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovats S. Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell Immunol. 2015;294:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson MA, Parrott JM, McCusker RH, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, O'Connor JC. Intracerebroventricular administration of lipopolysaccharide induces indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-dependent depression-like behaviors. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:87. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechawar N, Savitz J. Neuropathology of mood disorders: do we see the stigmata of inflammation? Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e946. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;16:22–34. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E. Harsh family climate in early life presages the emergence of a proinflammatory phenotype in adolescence. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:848–856. doi: 10.1177/0956797610370161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint AM, Kim YK, Verkerk R, Scharpe S, Steinbusch H, Leonard B. Kynurenine pathway in major depression: evidence of impaired neuroprotection. J Affect Disord. 2007;98:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor JC, Lawson MA, Andre C, Moreau M, Lestage J, Castanon N, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:511–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletti S, Myint AM, Schuetze G, Bollettini I, Mazza E, Grillitsch D, Locatelli C, Schwarz M, Colombo C, Benedetti F. Kynurenine pathway and white matter microstructure in bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00406-016-0731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AP, Bethea CL. Preliminary array analysis reveals novel genes regulated by ovarian steroids in the monkey raphe region. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:125–140. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai N, Ridker PM. Population distributions of C-reactive protein in apparently healthy men and women in the United States: implication for clinical interpretation. Clin Chem. 2003;49:666–669. doi: 10.1373/49.4.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Markey SP, Heyes MP. Effects of immune activation on quinolinic acid and neuroactive kynurenines in the mouse. Neuroscience. 1992;51:25–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90467-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Dantzer R, Wurfel BE, Victor TA, Ford BN, Bodurka J, Bellgowan PS, Teague TK, Drevets WC. Neuroprotective kynurenine metabolite indices are abnormally reduced and positively associated with hippocampal and amygdalar volume in bipolar disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015a;52:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Drevets WC, Smith CM, Victor TA, Wurfel BE, Bellgowan PS, Bodurka J, Teague TK, Dantzer R. Putative neuroprotective and neurotoxic kynurenine pathway metabolites are associated with hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in subjects with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015b;40:463–471. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Drevets WC, Wurfel BE, Ford BN, Bellgowan PS, Victor TA, Bodurka J, Teague TK, Dantzer R. Reduction of kynurenic acid to quinolinic acid ratio in both the depressed and remitted phases of major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015c;46:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieler L, Samuelsson M, Frye MA, Bhat M, Schuppe-Koistinen I, Jungholm O, Johansson AG, Landen M, Sellgren CM, Erhardt S. Electroconvulsive therapy suppresses the neurotoxic branch of the kynurenine pathway in treatment-resistant depressed patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:51. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0517-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovlund CW, Morch LS, Kessing LV, Lidegaard O. Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:1154–1162. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen CJ, Pedersen OB, Petersen MS, Sorensen E, Kotze S, Thorner LW, Hjalgrim H, Rigas AS, Moller B, Rostgaard K, Riiskjaer M, Ullum H, Erikstrup C. Combined oral contraception and obesity are strong predictors of low-grade inflammation in healthy individuals: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS) PLoS One. 2014;9:e88196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK, Budac DP, Bisulco S, Lee AW, Smith RA, Beenders B, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. NMDA receptor blockade by ketamine abrogates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior in C57BL/6J mice. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1609–1616. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KD, Drevets WC, Dantzer R, Teague TK, Bodurka J, Savitz J. Kynurenine pathway metabolites are associated with hippocampal activity during autobiographical memory recall in patients with depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;56:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.