Summary

The peptidoglycan is a rigid matrix required to resist turgor pressure and to maintain the cellular shape. It is formed by linear glycan chains composed of N-acetylmuramic acid-(β-1,4)-N-acetylglucosamine (MurNAc-GlcNAc) disaccharides associated through cross-linked peptide stems. The peptidoglycan is continually remodeled by synthetic and hydrolytic enzymes and by chemical modifications, including O-acetylation of MurNAc residues that occurs in most Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This modification is a powerful strategy developed by pathogens to resist to lysozyme degradation and thus to escape from the host innate immune system but little is known about its physiological function. In this study, we have investigated to what extend peptidoglycan O-acetylation is involved in cell wall biosynthesis and cell division of Streptococcus pneumoniae. We show that O-acetylation driven by Adr protects the peptidoglycan of dividing cells from cleavage by the major autolysin LytA and occurs at the septal site. Our results support a function for Adr in the formation of robust and mature MurNAc O-acetylated peptidoglycan and infer its role in the division of the pneumococcus.

Graphical Abstract

In this study, we have investigated to what extend peptidoglycan O-acetylation is involved in cell wall biosynthesis and cell division of Streptococcus pneumoniae. We show that Oacetylation driven by Adr protects the peptidoglycan of dividing cells from cleavage by the major autolysin LytA and occurs at the septal site. Our results support a function for Adr in the formation of robust and mature MurNAc O-acetylated peptidoglycan and infer its role in the division of the pneumococcus.

Introduction

The bacterial cell wall is essential since it contributes to the maintenance of the cell shape and sustains the basic cellular processes of growth and division. It is also crucial to resist turgor pressure and provides an interface between the cell and its environment. One of the major components of the bacterial cell wall is peptidoglycan, a matrix of linear glycan chains composed of disaccharides N-acetylmuramic acid-(β-1,4)-N-acetylglucosamine (MurNAc-GlcNAc) associated through peptide stems linked to MurNAc.

Assembly of the peptidoglycan network requires synthetic and hydrolytic enzymes. Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs) and SEDS proteins (Shape, Elongation, Division and Sporulation) (Meeske et al., 2016; Emami et al., 2017) polymerize the glycan chains (glycosyltransferase activity) while only PBPs cross-link the peptide strands (transpeptidation activity that is inhibited by β-lactam antibiotics) (for reviews on PBPs, see: Sauvage et al., 2008; Sauvage and Terrak, 2016; Egan et al., 2015). Endogenous peptidoglycan hydrolases cleave the peptidoglycan polymer in order to insert new material and to allow daughter cells separation and peptidoglycan maturation (Vollmer et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2000 for reviews). Peptidoglycan hydrolases are divided into different classes according to their cleavage site. N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidases hydrolyse the bond between MurNAc and L-alanine and thus separate the glycan strand from the peptide moiety. Carboxy- and endopeptidases cleave the stem peptide. N-acetylglucosaminidases and N-acetylmuramidases cut respectively the GlcNAc-MurNAc and MurNAc-GlcNAc bonds inside the glycan chains. Lastly, lytic transglycosylases cleave the glycosidic linkage between MurNAc-GlcNAc and GlcNAc-MurNAc residues with the concomitant formation of a 1,6-anhydromuramoyl product.

Chemical modifications of the glycan strands participate to peptidoglycan remodeling. Removal of the N-acetyl groups is most often observed in Gram-positive bacteria and the best characterized enzyme in charge of this reaction is the N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase PgdA from Streptococcus pneumoniae (Blair et al., 2005). The peptidoglycan glycan chains can be acetylated also on their C6-OH groups (O-acetylation). O-acetylation of GlcNAc has only been detected in Lactobacillus and Bacillus species (Bernard et al., 2011; Laaberki et al., 2011). By contrast, O-acetylation of MurNAc is present in most Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with the exception of Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteria (for more details see the reviews; Vollmer, 2008a; Moynihan and Clarke, 2011). Interestingly, the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria contains wall teichoic acids (WTA), which are glycopolymers linked to the C6-OH group of MurNAc. This indicates that WTA decoration and O-acetylation of MurNAc are mutually exclusive (Brown et al., 2013 for review).

O-acetylation of MurNAc residues is a two-step process. Firstly, the acetyl group from a donor molecule is transported from the cytoplasm to the periplasm or the extracellular space. Secondly, the acetyl group is transfered to the C6-OH group. In Gram-negative bacteria, these steps are performed by two different proteins: the integral membrane protein PatA transports the acetyl-donor and the inner membrane-anchored protein PatB catalyzes the acetylation reaction (Moynihan and Clarke, 2010). Conversely, in Gram-positive bacteria, these functions are held by a single protein, OatA, formed by two domains: the N-terminal domain composed by 11 transmembrane helices that supposedly transfers the acetyl group to the C-terminal domain exposed in the extracellular space, which catalyzes the O-acetylation of MurNAc (Bera et al., 2005).

In many bacteria including important human pathogens like S. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and N. meningiditis, N-deacetylation and/or O-acetylation of MurNAc and GlcNAc residues were shown to provide resistance to lysozyme, a N-acetylmuramidase enzyme found in human tears, saliva, and gastrointestinal tract (Callewaert and Michiels, 2010 for review; Davis and Weiser, 2011). The substrate-binding site of lysozyme involves amino acids residues that interact with the acetyl groups as well as residues lining the active site that recognize C6-OH groups of MurNAc (Blake et al., 1965; Vocadlo et al., 2001). By consequence, acetylation of the glycan residues causes a steric hindrance that reduces the affinity of lysozyme for the C6-OH groups (Moynihan and Clarke, 2011).

In Gram-negative bacteria, peptidoglycan O-acetylation is also involved in lysozyme resistance, cell wall metabolism, pathogenesis (Moynihan et al., 2011; Moynihan et al., 2014 for reviews) and has also been shown to have a role in biofilm formation in Campylobacter jejuni (Iwata et al., 2016). The genes cluster encoding PatA and PatB also encodes an O-acetylpeptidoglycan esterase, Ape, responsible for O-acetyl group removal. PatA/PatB and Ape function together to regulate the lytic transglycosylase activity of autolysins involved in the peptidoglycan metabolism, which would be a means to localize the hydrolyic activities (Weadge et al., 2005; Weadge and Clarke, 2006). This genes cluster is also present in some Gram-positive bacteria from the Bacillus genus (Weadge et al., 2005) and play a role in cell division and anchoring of S-layer to the cell surface (Laaberki et al., 2011). However, Gram-positive bacteria which O-acetylate their peptidoglycan only by OatA homologs do not possess O-acetylpeptidoglycan esterase.

Beside the importance of peptidoglycan O-acetylation as a molecular determinant in the interaction with the host organism, little is known about the function of this modification in bacterial physiology. In this work, we have investigated the role of peptidogylcan O-acetylation in the peptidoglycan resistance to endogenous hydrolases, peptidoglycan synthesis and cell division. This question has been addressed in the context of the human pathogen Gram-positive bacterium S. pneumoniae in which peptidoglycan O-acetylation is performed by the homologous of OatA named Adr (Attenuated drug resistance), since the absence of Adr resulted in the loss of peptidoglycan O-acetylation (Crisóstomo et al., 2006). Here, we show that peptidoglycan O-acetylation protects growing pneumococcal cells from lysis induced by the major pneumococcal autolysin LytA. In addition, we demonstrate that peptides cross-links and O-acetylation are peptidoglycan maturation processes functionally related and that Adr is also linked to the cell division machinery.

Results

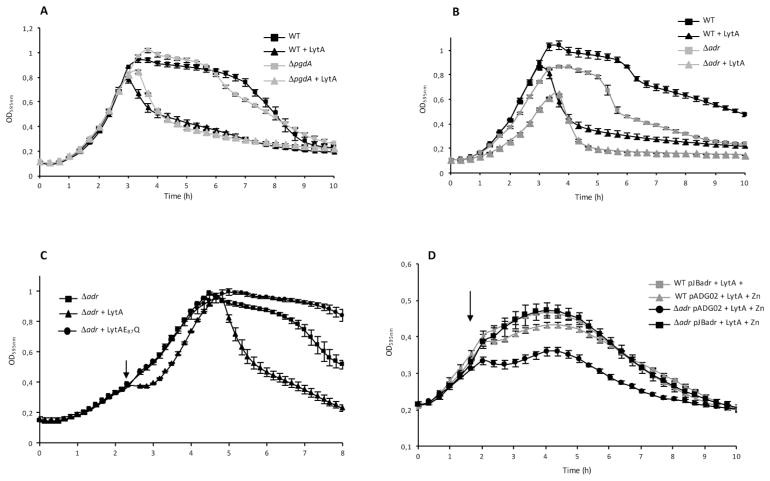

The absence of Adr expression increases S. pneumoniae LytA-dependent lysis during exponential growth

PgdA and Adr proteins are responsible for peptidoglycan N-deacetylation and O-acetylation in S. pneumoniae, respectively. Since both modifications have been shown to protect peptidoglycan from lysozyme cleavage, we wondered whether they affect the action of the major pneumococcal autolysin LytA (Tomasz, 1968; Howard and Gooder., 1974). LytA is an amidase responsible for autolysis during stationary phase, penicillin induced lysis and also involved in fratricide. The pneumococcus is sensitive to this amidase only when the cells enter into the stationary phase, during nutrient depletion or if the peptidoglycan biosynthesis machinery is inhibited by antibiotics (Tomasz and Waks, 1975; Mellroth et al., 2012), suggesting that the sensitivity of the peptidoglycan towards LytA is primarily driven by the peptidoglycan machinery activity. The ΔpgdA and Δadr mutant strains were tested for their sensitivity towards LytA. Wild-type (WT) and mutant strains were grown in the absence or in the presence of purified LytA, added in the culture at the final concentration of 10 μg/ml (Figs. 1A and 1B). The WT and ΔpgdA strains were equally resistant to LytA during exponential growth but became sensitive to the amidase at the onset of stationary phase since rapid decrease of OD595nm was observed in cultures containing LytA compared to the cultures performed in the absence of LytA (Fig. 1A). This observation indicates that the N-acetylation pattern of the peptidoglycan is not involved in the protection from LytA cleavage during exponential growth. By contrast, the Δadr strain is sensitive to LytA in exponential phase since growth was slowed down in the presence of LytA when compared to the WT strain (Fig. 1B). We noticed that in the absence of exogenous LytA, the culture does not reach the same maximal density as the WT strain and the autolysis process takes place earlier for the mutant than for the WT strain, indicating that the Δadr strain is more sensitive to the action of released endogenous LytA (Fig. 1B). Deletion of the endogenous lytA in the WT and Δadr genetic backgrounds did not affect sensitivity towards exogenous LytA suggesting that Adr alone is responsible for the observed phenotype (Fig. S1).

Figure 1. Effect of LytA on pneumococci in exponential growth phase in CY medium.

A. Growth curves of WT and ΔpgdA strains in the absence or in the presence of LytA at 10 μg/ml.

B. Growth curves of WT and Δadr strains in the absence or in the presence of LytA at 10 μg/ml.

C. Growth curves of Δadr strain in the presence of active LytA or inactive LytAE87Q forms, both proteins (final concentration of 10 μg/ml) were added at mid-exponential phase, OD595nm 0.3–0.4 as indicated by the arrow.

D. Complementation of the adr gene deletion. The pneumococcal Δadr or the WT strains were transformed with the Zn-inducible plasmid pJBadr containing a copy of adr or with the empty plasmid (pADG02). Active LytA (10 μg/ml) was added at mid-exponential phase (OD595nm 0.3–0.4, arrow).

Complementary experiments were performed by adding purified LytA at the final concentration of 10 μg/ml into the culture at mid-exponential growth phase (Figs. 1C and 1D). While the WT growth was sligthly reduced, a growth arrest was observed as soon as LytA was added to the Δadr culture (Fig. 1C). Importantly, no effect was detected upon addition of the inactive LytAE87Q variant, indicating that the enzymatic activity of LytA (and not the protein presence) accounts for the impairement of the growth rate during Δadr exponential phase (Fig. 1C). As expected, no effect of the LytAE87Q form was observed on the WT strain (Fig. S2). To verify that the effect of adr deletion was not polar, the Δadr strain was complemented with an ectopic copy of the adr gene placed under the control of a Zn-inducible promoter. The Δadr strains carrying the plasmid encoding adr (pJBadr) or the empty plasmid (pADG02) were grown in the presence of Zn (Fig. 1D). As expected, in the absence of adr, growth was arrested as soon as LytA was added in the culture at mid-exponential phase (OD595nm 0.3) while expression of the ectopic copy of adr allowed cells to multiply and reach OD595nm 0.5 (Fig. 1D). This result shows that the presence of Adr restored the protection against LytA although the WT phenotype was not fully recovered (Fig. 1D and S3), most probably because the expression level from the Zn-inducible promoter is lower than the endogenous expression level (Eberhardt et al., 2009; Morlot et al., 2013).

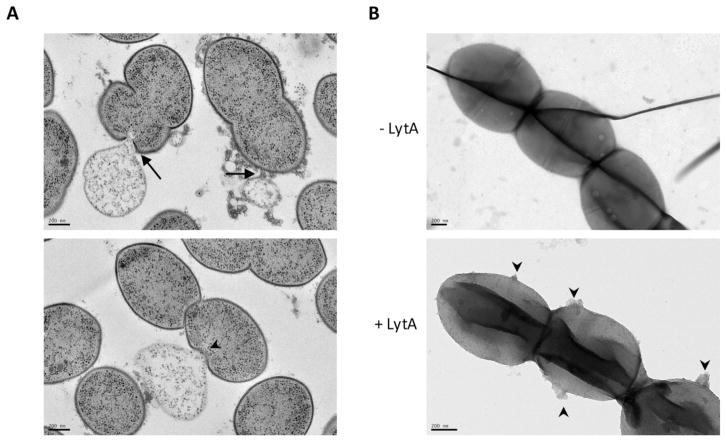

We next wondered whether the sensitivity of the Δadr strain to LytA during exponential growth was associated with cell lysis. To investigate this phenomenon, growing Δadr cells incubated with LytA were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). To preserve cellular ultrastructure, cells were vitrified by high-pressure freezing, gradually embedded with agar resin in acetone and 70-nm sectionned (see Materials for complete description of the procedure). Electron micrographs of ultrathin sections of Δadr cells showed disruptions of the cell enveloppe at the poles (Fig. 2A, arrows) and at the septal site (Fig. 2A, arrow heads), causing the release of cytoplasmic content. Statistical analysis of images such as those shown in Fig 2A revealed that 16% of Δadr cells (n=280) were lyzing while this phenomenon occurred only in 5% of the WT cells (n=340). These values are not absolute because the counting procedure discards a majority of cells not sectioned in the longitudinal axis. However, these data are representative of the global behavior of the cell population and they are further supported by the observation of similar LytA-induced lysis events in whole Δadr cells observed by TEM (Fig. 2B, arrow heads). We then propose that the growth delay induced by LytA observed in Δadr cultures is due to the killing of the LytA-targeted cells while non-lyzed neighboring cells continue to divide until stationary phase is reached. Altogether, these data show that in the absence of Adr, LytA is able to lyse pneumoccocal cells during exponential growth indicating that O-acetylation protects the peptidoglycan from LytA cleavage.

Figure 2. LytA induces cell lysis of growing cells harbouring unacetylated peptidoglycan.

A. Transmission electron micrographs of thin sections of Δadr cells harvested at mid-exponential growth phase and incubated with 10 μg/ml of LytA for 20 min at 37°C/CO2 in CY medium. Cell lysis occuring at the poles (arrows) and at the septal site (arrow heads) are shown, as well as ejection of cytoplasmic material. Scale bars, 200 nm.

B. Cells treated as in A were observed by transmission electron microscopy. In the absence of LytA, the cell surface is smooth (upper panel, scale bar 200 nm) while the action of LytA (incubation time of 20 min) induced extrusions at the cell surface (lower panel, arrow heads). Scale bar, 200 nm).

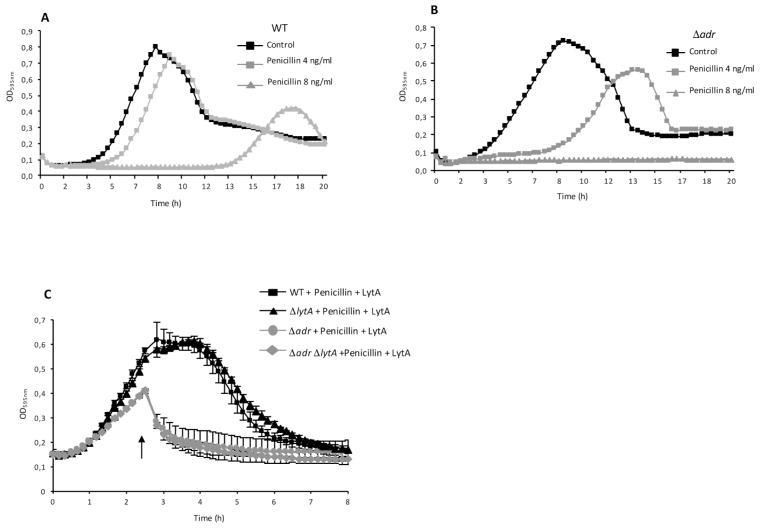

The absence of Adr expresssion increases S. pneumoniae sensitivity to β-lactams

We showed that growing pneumococcal cells are more sensitive to LytA in the absence of Adr. Moreover, LytA sensitivity was also observed when peptidoglycan synthesis was inhibited by β-lactam antibiotics (Mellroth et al., 2012). We thus wondered whether inhibition of peptidoglycan biosynthesis and absence of O-acetylation would have a cumulative effect on LytA sensitivity.

The sensitivity of Δadr and WT strains to penicillin was investigated by comparing the growth profiles of these strains in the presence of 4 and 8 ng/ml of penicillin, which are concentrations lower than the minimal inhibitory concentration value (16 ng/ml). Growth of the WT strain was only slightly delayed (by about 1 h) in the presence of 4 ng/ml of penicillin and largely delayed (by about 10 h) by 8 ng/ml of penicillin (Fig. 3A). Growth of the Δadr strain was much more delayed (by about 5 h) at the lower concentration of penicillin and no growth was observed in the presence of 8 ng/ml of penicillin (Fig. 3B). Since LytA is known to trigger lysis in the presence of penicillin, similar experiments were performed in the ΔlytA genetic background to assess the specific role of Adr in penicillin sensitivity (Fig. S4). Comparable patterns were obtained when compared to the WT strain, indicating that peptidoglycan O-acetylation is important to resist to penicillin-induced lysis as observed previously (Crisóstomo et al., 2006) and that it acts independently from endogenous LytA. Since the Δadr strain appeared to be more sensitive to lysis induced by LytA and penicillin, we wondered whether these effects would be cumulative. Cultures of the WT, Δadr, ΔlytA and ΔadrΔlytA strains were performed in the presence of 8 ng/ml of penicillin and LytA was added at mid-exponential phase. Single Δadr and double ΔadrΔlytA strains were more sensitive to lysis in the presence of both penicillin and LytA than the WT and ΔlytA strains (Figs. 3C and S5). In conclusion, the absence of MurNAc O-acetylation and the decrease of peptides cross-link (as the consequence of the transpeptidation inhibition by penicillin) generate a weak peptidoglycan matrix highly sensitive to lysis. These data suggest that the cross-link of peptides catalyzed by the PBPs and the O-acetylation of MurNAc performed by Adr might be functionally dependent activities.

Figure 3. Unacetylated peptidoglycan is more sensitive to penicillin-induced lysis.

A. Growth curves of WT strain in the absence or the presence of penicillin at 4 and 8 ng/ml.

B. Growth curves of Δadr strain in the absence or the presence of penicillin at 4 and 8 ng/ml.

C. Sensitivity to cell lysis mediated by penicillin (4 ng/ml) and LytA (10 μg/ml), the latter was added at mid-exponential phase (arrow).

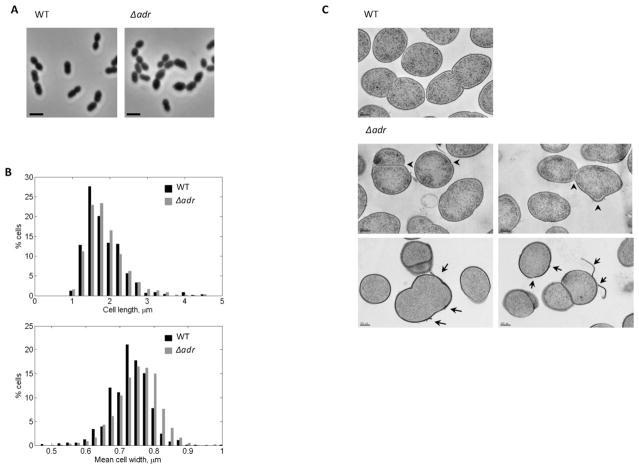

Morphology and cell wall defects of the Δadr strain

To further study the relationship between O-acetylation and peptidoglycan synthesis, we analyzed the morphology of the Δadr strain by light microscopy. A significant proportion of Δadr cells (about 36 %) were wider than the WT cells (Figs. 4A and 4B). Additional analysis of morphological defects displayed by Δadr cells was performed by TEM in conditions that preserve cellular ultrastructures as described above. The mutants cells revealed altered shape with misplaced or non-linear septa (Fig. 4C arrow heads). The cell wall of Δadr cells also presented important structural defects since fragments detaching from the cell surface were observed (Fig. 4C arrows). Altogether, these results confirm that in the absence of O-acetylation, the peptidoglycan network is less structured, which in turn impacts the cell morphology.

Figure 4. Morphological analysis of pneumococcal Δadr cells.

A. Phase contrast microscopy images of WT and Δadr exponentially growing cells in CY medium. Scale bars, 2 μm.

B. Distribution of the length (upper panel) and width parameters (lower panel) of Δadr cells compared to WT cells. Measurements were performed on at least 700 cells based on phase-contrast images using MicrobeTracker.

C. Transmission electron micrographs of thin sections of Δadr cells harvested at mid-exponential growth phase. Scale bars, 200 nm. Arrow heads indicate defective septal initiation sites and arrows point to cell wall peeling and destructurations.

Adr co-localizes with the division machinery at the onset of the cell cycle

Defects of the Δadr strain in peptidoglycan integrity and in cellular morphology suggest that Adr function might be coupled to the activity of the division machinery. To investigate this, we first assessed the cellular localization of Adr using fluorescence microscopy. The C-terminal end of Adr (Fig. S6A) was fused to the superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) variant, which was engineered to display more robust refolding properties (Pédelacq et al., 2006) and was successfully used to detect fusion proteins exported in the periplasm of E. coli (Dammeyer and Tinnefield, 2012; Dinh and Bernhardt, 2011). The sfGFP gene was optimized for expression in S. pneumoniae (sfGFPop) and fused to the 3′ end of the adr gene at the chromosome locus. The pneumococcal strain expressing the Adr-sfGFPop variant displayed the same resistance pattern to LytA than the WT strain indicating that the fusion protein is functional (Fig. S6B). Wide-field microscopy images showed that like most of the division and cell wall synthesis proteins, Adr is positioned at the parental division site and at the future division sites of daughter cells (Figs. 5A and 5B) (Supplementary Video 1).

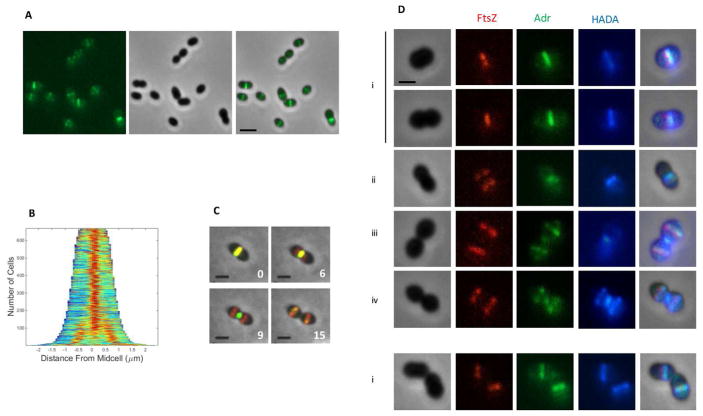

Figure 5. Localization of Adr in WT cells.

A. Adr-sfGFPop localization in WT cells. GFP fluorescent signal (left), phase contrast (middle) and merge (right) images are shown. Scale bars, 2 μm.

B. Demograph of a pneumococcal cell population expressing Adr-sfGFPop.

C. Fluorescence time-lapse microscopy of WT cells producing FtsZ-mKate2 and Adr-sfGFPop. Overlays between phase contrast (gray), GFP (green) and mKate (red) are shown. Stills are from Movie S2. Scale bar, 2 μm.

D. Pulse labeling with HADA of WT cells producing FtsZ-mKate2 and Adr-sfGFPop. Marks i to iv indicate stages of cell division. Scale bars, 2 μm.

To determine whether Adr is an early or late division protein, we introduced the adr-sfGFPop construct in a pneumococcal strain expressing a FtsZ-mKate2 fusion (Fig. S6C). Time-lapse experiments revealed that Adr co-localizes with FtsZ at mid-cell only during the first division stages in the mother cell and in the daughter cells when they are about to initiate a new round of division (Fig 5C, panels 0 and 15 min and Supplementary Video 2). When FtsZ rings re-assembles at the future division sites of the newly formed daughter cells, Adr remains mainly associated to the parental septal site (Fig 5C, panels 6 and 9 min and Supplementary Video 2). In conclusion, Adr localizes at the cell division site all along the cell cycle but its positioning lags behind the one of FtsZ. This postponed pattern of Adr relative to FtsZ localization is reminiscent of that of the PBPs (Morlot et al., 2013; Morlot et al., 2003; Tsui et al., 2014). To determine the timing of Adr localization relative to peptidoglycan synthesis, the regions of active peptidoglycan synthesis were labeled by short incubation times with fluorescently labelled D-amino acids (HADA) (Kury et al., 2012) (Fig. 5D). At early division stages (i), FtsZ and Adr co-localize at mid-cell where new peptidoglycan is synthesized. When FtsZ rings re-localizes to the future division sites, Adr remains associated to the parental site where HADA labelling can still be detected (ii). At mid-division stage (iii), Adr migrates to the future division sites before peptidoglycan synthesis takes place, which occurs later on as shown by HADA labelling at the equator of the future daughter cells (iv). These data indicate that although Adr localizes to the septal site right after FtsZ, its positioning precedes peptidoglycan synthesis reported by fluorescent D-amino acids incorporation.

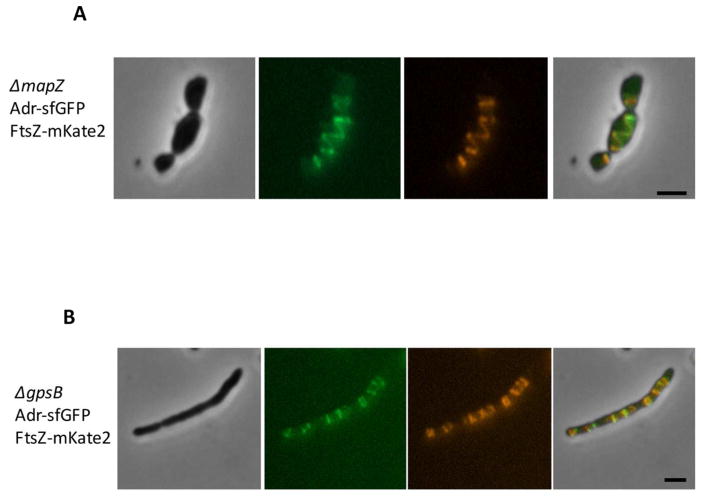

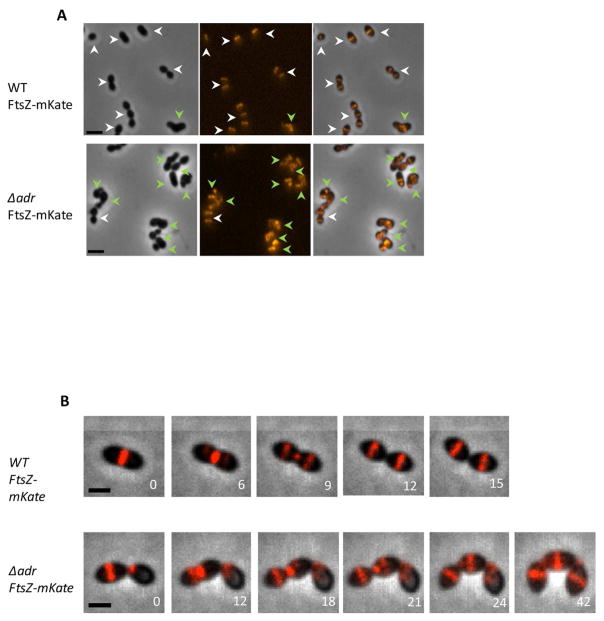

Maintenance of the bacterial cell shape is a complex process that involves multi-protein machineries composed by peptidoglycan biosynthetic enzymes and regulatory proteins (Egan et al., 2015; Massida et al., 2013 for reviews). Among those, we focused on two proteins: MapZ that forms ring structures at the division site and locates FtsZ through direct protein-protein interactions (Fleurie et al., 2014a) and the essential protein GpsB that is involved in the early closure of the septal ring (Land et al., 2013, Fleurie et al., 2014b). The localizations of Adr-sfGFPop and FtsZ-mKate2 were analyzed in the ΔmapZ and ΔgpsB backgrounds (Fig. 6). FtsZ-mKate2 displayed helical organization and ladder-like positioning in ΔmapZ and ΔgpsB strains, respectively, as already described (Fleurie et al., 2014a; Fleurie et al., 2014b; Land et al., 2013). Interestingly, Adr-sfGFPop perfectly co-localized with FtsZ-mKate2 in these two strains (Fig. 6). It is worth mentioning that no significant alteration of Adr positioning was observed in Δpbp1a, Δpbp2a, Δpbp1b and Δpbp3cter strains (Fig. S7) (Paik et al., 1999; Schuster et al., 1990). FtsZ-mKate2 was expressed in Δadr cells and 79,5 % (n=565) of those cells present abnormal morphologies and FtsZ defects positioning compared to only 12,3 % (n=553) of the WT cells expressing FtsZ-mKate2 (Fig. 7A). In addition, time-lapse images of FtsZ-mKate2 show efficient cell division and septal localization in WT cells while aberrant division and morphological defects appear in the Δadr strain together with altered FtsZ-mKate2 positioning (Fig. 7B and Supplementary Video 3). In conclusion, the expression of FtsZ-mKate2 in Δadr cells induces a more severe phenotype than in the WT cells indicating that this fusion is not fully functional. The partial loss of FtsZ function when it is fused to fluorescent protein has already been reported (Marteyn et al., 2014). Altogether, these data show that in pneumococcal WT cells and in division mutants, Adr and FtsZ co-localize, strongly suggesting that the function of Adr is related to the cell division process.

Figure 6. Mislocalization of Adr and FtsZ-mKate2 in ΔmapZ and ΔgpsB cells.

A. Adr-sfGFPop and FtsZ-mKate2 localizations in ΔmapZ cells. Phase contrast (grey), GFP fluorescent signal (green), mKate2 (red) and merge (right) images are shown. Scale bars 2 μm.

B. Adr-sfGFPop and FtsZ-mKate2 localizations in ΔgpsB cells. Phase contrast (grey), GFP fluorescent signal (green), mKate2 (red) and merge (right) images are shown. Scale bars 2 μm.

Figure 7. Mislocalization of FtsZ-mKate2 in Δadr cells.

A. FtsZ-mKate2 localization in WT and Δadr cells. Phase contrast (left), red fluorescent signal (middle) and merge (right) images are shown. White arrow heads point to cells of normal morphology and septal localization of FtsZ while green arrow heads point to cells displaying aberrant shape and mislocalization of FtsZ. Scale bar, 2 μm.

B. Distribution of the length parameter (upper panel) and width parameter (lower panel) of Δadr cells (n=1786) compared to Δadr cells expressing FtsZ-mKate2 (n=928). Measurements were performed on phase-contrast images using MicrobeTracker. C. Fluorescence time-lapse microscopy of WT cells producing FtsZ-mKate2 and Δadr cells expressing FtsZ-mKate. Overlays between phase contrast (grey), GFP (green) and mKate2 (red) are shown. Stills are from Movie S3. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Discussion

Deletion of adr gene encoding an O-acetylase increases LytA-dependent lysis of S. pneumoniae during exponential growth phase. From these results, we infer that O-acetylation of MurNAc residues protects peptidoglycan from cleavage of the amide bond by LytA. In addition, the absence of Adr increases sensibility to penicillin. This implies a functional relationship between peptidoglycan O-acetylation and its cross-linking. Furthermore, the O-acetylation Adr localizes at the septal site and adopts aberrant positioning in cell division mutants, indicating that O-acetylation is functionally related to cell division. We propose that Adr is an important player of the pneumococcal division process by promoting the formation of robust and mature peptidoglycan, although we cannot formely exclude a minor compensatory effect of other activities in peptidoglycan metabolism.

LytA cleaves the amide bond between MurNAc and L-alanine (Howard and Gooder, 1974) and is responsible for the pneumococcal autolysis launched at the end of the stationary phase. Although LytA acts at the cell surface, the mechanism of its export remains unclear since no peptide signal is present in its sequence. Recently, it was shown that LytA is released during exponential growth phase and accumulates at the cell surface all along the stationary phase until a threshold concentration (proposed to be about 0.5 μg/ml) is attained and initiates the lysis process (Mellroth et al., 2012). Pneumococcal cells are protected from the amidase activity of LytA during the exponential growth phase but these protective features are lost when the peptidoglycan biosynthesis machinery is stopped upon entry into the stationary phase, nutrient depletion or inhibition by antibiotics (Tomasz and Waks, 1975; Mellroth et al., 2012).

O-acetylation reaction must be performed on nascent peptidoglycan since no O-acetylated groups has been detected on the precursor lipid II (see Vollmer, 2008a for review). Our data suggest that O-acetylation of MurNAc is related to peptidoglycan formation since inhibition of the transpeptidase activity of PBPs by penicillin resulted in an increase of LytA activity. We thus propose that Adr function is tightly related to the cross-linking of newly polymerized glycan chains and that the joined O-acetylation and transpeptidation reactions contribute to form a robust peptidoglycan structure. Interestingly, a sum of observations reviewed in 2008 (Vollmer, 2008a) and yet not updated led to the same hypothesis, i.e., peptidoglycan O-acetylation would be linked to the cross-linking of peptidoglycan. It was shown that the level of peptidoglycan O-acetylation was decreased after incubation with penicillin in S. aureus (Sidow et al., 1990) and Proteus mirabilis (Martin and Gmeiner, 1979). In N. gonorrhoeae, this same effect was shown to be associated to the inhibition of PBP2 (Dougherty, 1983; Dougherty, 1985). Moreover, in a penicillin-resistant strain of S. pneumoniae, the absence of Adr resulted in the loss of O-acetylation and in the reduction of the minimal inhibitory concentration of penicillin, indicating that O-de-acetylated peptidoglycan is more sensitive to the lysis induced by penicillin (Crisóstomo et al., 2006). We observed a comparable phenotype although a penicillin-sensitive strain was used. Altogether, the data presented here suggest that O-acetylation is an important step in the synthesis of fully structured peptidoglycan. As illustrated in Fig. 8, we propose that O-acetylation and transpeptidation activities are functionally related.

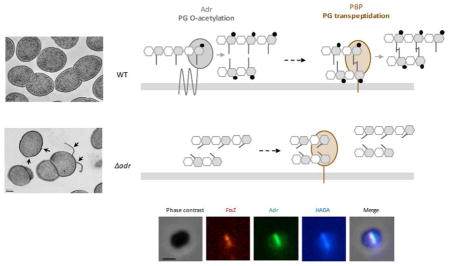

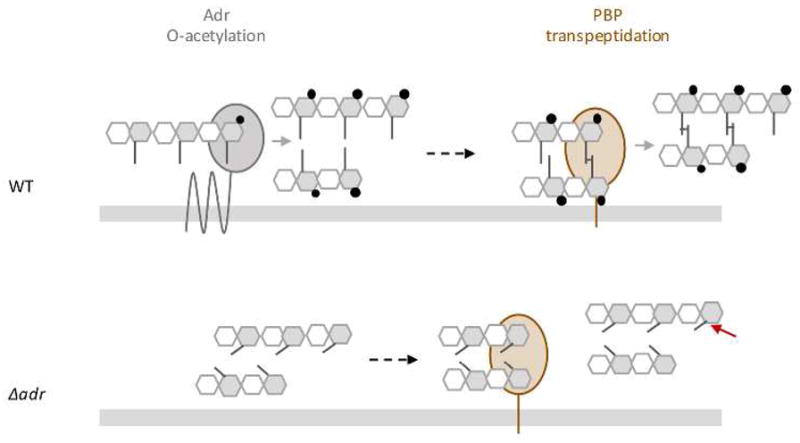

Figure 8. Model of the functional interplay between O-acetylation and transpeptidation.

Adr protein which catalyzes the O-acetylation reaction is represented as a multimembrane protein (for details, see Fig S6A). Only one PBP is represented as a bitopic membrane protein with the catalytic domain exposed in the extracellular space. For clarity reason, the represented PBP only refers to the transpeptidation reaction, the glycan chain polymerization activity is not shown. The grey bar accounts for the cytoplasmic membrane. The peptidoglycan glycan chains are formed by the repetition of MurNAc and GlcNAc, grey and white hexagons, respectively. Peptide stems (grey lines) are linked to MurNAc and cross-linked to each other (transversal lines). O-acetylation of MurNAc residues is represented by black circles. Light grey arrows indicate O-acetylation and transpeptidation reactions. The dotted black arrow illustrates the fact that O-acetylation of MurNAc would precede peptides cross-linking in our working model. Non cleavage of the amide bond by LytA in O-acetylation peptidoglycan is indicated by a diamond red arrow, while cleavage when peptidoglycan is O-de-acetylated is represented by a red arrow.

In dividing WT cells where exponential growth and peptidoglycan synthesis take place (upper panel), Adr O-acetylates MurNAc residues on glycan strands before transpeptidation to produce mature peptidoglycan. In such a structure, the amide bond is not accessible, impeding its cleavage by LytA and thus conferring resistance towards cell lysis. The absence of Adr (Δadr strain) induces alteration of the peptidoglycan structure, which in turns affects the transpeptidation efficiency, increases the sensitivity to LytA cleavage (the amide bond cleavage site is indicated by the red arrow), alters the cell morphology and impacts the division process (the latter two features are not represented in the figure).

We investigated the role of O-acetylation in cellular division and we show that indeed, Adr protein actively participates in the pneumococcal division process. To our knowledge, this is only the second example of such investigation together with OatA in Lactobacillus plantarum, which has been shown to control cell septation independently of its O-acetyltransferase activity (Bernard et al., 2012). Δadr pneumococcal cells display defects in the cell wall structure and in the septation process. Interestingly, cell division alterations and aberrant FtsZ localizations are observed in the Δadr mutant indicating that Adr and FtsZ activities are jointly required for efficient pneumococcal division. The positioning of Adr in pneumococcal cells is reminiscent of proteins acting in the division process, like FtsZ, StkP and PBPs (Morlot et al., 2003; Morlot et al., 2013; Jacq et al., 2015). Like StkP and PBPs, the septal localization of Adr lags just behind FtsZ, which itself is beaconed by MapZ (Fleurie et al., 2014a). Monitoring of peptidoglycan synthesis by incorporation of the HADA fluorescent label by the PBPs further showed that at the mid-division stage, Adr migrates to the future division sites before peptidoglycan synthesis takes place, i.e. before the future division sites of daughter cells are marked by HADA. Adr localization timing is thus compatible with a concerted action with the PBPs and this is in agreement with the idea that peptidoglycan O-acetylation is an important reaction in the process of peptidoglycan synthesis and maturation as well as in cell division. Future experiments will aim at determining whether the role of Adr in cell wall synthesis and division involves its enzymatic activity and/or molecular interaction with components of the division machinery.

Experimental procedures

Plasmid construction and site-directed mutagenesis

The construction of pJBadr construction required intermediate steps performed as follows. pCM38 (Jacq et al., 2015) derives from pJWV25 (Eberhardt et al., 2009) that contains a AgeI/SpeI cassette encoding the GFP+ under the control of the PczcD promoter [bgaA::PZn-gfp+] (AmpR, TetR). The gene encoding the superfolder GFPop was digested by AgeI and SpeI from pCM83 and the fragment was inserted into pCM38 between AgeI and SpeI [bgaA::PczcD-sfGFPop]. Insertion of the BssHII and BsiWI restriction sites was performed by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis upstream of the AgeI restriction site in pCM83 and results in pADG0. pADG02 corresponds to pADG0 from which the sfGFPop gene was removed by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis [bgaA::PczcD]. The adr gene was amplified by PCR with FORoJB57 and REVoJB58 primers, digested by BssHII and BsiWI and inserted into pADG02 between BssHII and BsiWI [bgaA::PczcD-adr] to generate pJBadr.

Mutations were introduced by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and verified by DNA sequencing (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Genewiz).

Bacterial strains and plasmids

The strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers used are listed in Table 1. The synthetic gene encoding the superfolder variant of GFP (sfGFPop) was optimized for expression in S. pneumoniae and ordered from GeneArt (Invitrogen). Allelic replacements were performed using the Janus method, a two-step procedure based on a bicistronic kan-rpsL cassette called Janus (Sung et al., 2001). This method avoids polar effects and allows expression of the fusion proteins at physiological levels.

Table 1.

| Constructs | Genotype/description/sequence | Source |

|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae strains | ||

| R6 | ||

| R800 | R6 rpsL1; StrR | Sung et al., 2001 |

| ftsZ-kan-rpsL | R800; ftsZ::ftsZ-kan-rpsL; KanR | Fleurie et al., 2014a |

| ftsZ-mKate | R800 ftsZ::ftsZ-mKate; StrR | This work |

| R800 PZn-adr | R800 bgaA::PczcD –adr (pJBadr); StrR, TetR | This work |

| R800 PZn | R800 bgaA::PczcD (pADG02); StrR, TetR | This work |

| R6 ΔlytA | R6 lytA::cat; CatR | Pagliero et al., 2008 |

| ΔlytA | R800 lytA::cat; StrR CatR | This work |

| Δadr-kan-rpsL | R800 adr::kan-rpsL; KanR | This work |

| Δadr | R800 adr::Δadr; StrR | This work |

| Δadr PZn-adr | R800 adr::Δadr bgaA::PczcD –adr (pJBadr); StrR, TetR | |

| Δadr PZn | R800 adr::Δadr bgaA::PczcD (pADG02); StrR, TetR | |

| ΔpgdA-kan-rpsL | R800 pgdA::kan-rpsL, KanR | This work |

| Δadr ΔlytA | R800 adr::Δadr lytA::cat; StrR, CatR | This work |

| ΔpgdA ΔlytA | R800 pgdA::kan-rpsl lytA::cat; KanR, CatR | This work |

| adr-sfGFPop | R800 adr::adr-sfGFPop; StrR | This work |

| Δadr ftsZ-kan-rpsL | R800 adr::Δadr ftsZ::ftsZ-kan-rpsL; KanR | This work |

| Δadr ftsZ-mKate | R800 adr::Δadr; ftsZ::ftsZ-mKate; StrR | This work |

| Δadr-kan-rpsL ftsZ-mKate | R800 adr::kan-rpsL; ftsZ::ftsZ-mKate; KanR | This work |

| adr-sfGFPop ftsZ-mKate | R800 adr::adr-sfGFPop ftsZ::ftsZ-mKate; StrR | This work |

| ΔmapZ | R800 mapZ:: ΔmapZ; StrR | Fleurie et al., 2014a |

| ΔmapZ Δadr-kan-rpsL | R800 mapZ:: ΔmapZ adr::kan-rpsL;KanR | This work |

| ΔmapZ adr-sfGFPop ftsZ-mKate | R800 mapZ:: ΔmapZ adr::adr-sfGFPop ftsZ::ftsZ-mKate; StrR | This work |

| ΔgpsB | R800 gpsB:: gpsB; StrR | Fleurie et al., 2014b |

| ΔgpsB Δadr-kan-rpsL | R800 gpsB:: gpsB adr::kan-rpsL;KanR | This work |

| ΔgpsB adr-sfGFPop ftsZ-mKate | R800 gpsB:: gpsB adr::adr-sfGFPop ftsZ::ftsZ-mKate; StrR | This work |

| Δpbp1a | R6, CatR | Paik et al., 1999 |

| Δpbp1a rpsL1 | R6 rpsL1 pbp1a::cat; CatR, StrR | This work |

| Δpbp1a Δadr-kan-rpsL | R6 rpsL1 pbp1a::cat adr::kan-rpsL; CatR, KanR | This work |

| Δpbp1a adr-sfGFPop | R6 rpsL1 pbp1a::cat adr::adr-sfGFPop; CatR, StrR | This work |

| Δpbp1b | R6, CatR | Paik et al., 1999 |

| Δpbp1b rpsL1 | R6 rpsL1 pbp1b::cat; CatR, StrR | This work |

| Δpbp1b Δadr-kan-rpsL | R6 rpsL1 pbp1b::cat adr::kan-rpsL; CatR, KanR | This work |

| Δpbp1b adr-sfGFPop | R6 rpsL1 pbp1b::cat adr::adr-sfGFPop; CatR, StrR | This work |

| Δpbp2a | R6, CatR | Paik et al., 1999 |

| Δpbp2a rpsL1 | R6 rpsL1 pbp2a::cat; CatR, StrR | This work |

| Δpbp2a Δadr-kan-rpsL | R6 rpsL1 pbp2a::cat adr::kan-rpsL; CatR, KanR | This work |

| Δpbp2a adr-sfGFPop | R6 rpsL1 pbp2a::cat adr::adr-sfGFPop; CatR, StrR | This work |

| Δpbp3 | R6, dacAC-ter::ery; EryR | Schuster et al., 1990 |

| Δpbp3 rpsL1 | R6 rpsL1, dacAC-ter::ery; EryR | This work |

| Δpbp3 Δadr-kan-rpsL | R6 rpsL1 dacAC-ter::ery adr::kan-rpsL; EryR, KanR | This work |

| Δpbp3 adr-sfGFPop | R6 rpsL1 dacAC-ter::ery adr::adr-sfGFPop; EryR, StrR | This work |

| ΔspxB | R6 spxB::kan; KanR | This work |

| ΔspxB ΔlytA | R6 spxB::kan adr::cat; KanR, CatR | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJWV25 | [bgaA::PZn-gfp+], AmpR, TetR | Eberhardt et al., 2009 |

| pCM38 | [bgaA::PZn-gfp+], AmpR, TetR, AgeI | This work |

| pCM83 | [bgaA::PZn-sfgfpopt], AmpR, TetR, AgeI | This work |

| pADG0 | [bgaA::PZn-sfgfpopt], AmpR, TetR, AgeI, BssHII, BsiWI | This work |

| pADG02 | [bgaA::PZn], AmpR, TetR, AgeI, BssHII, BsiWI | This work |

| pJBadr | [bgaA::PZn-adr], AmpR, TetR, AgeI, BssHII, BsiWI | This work |

| pET28-His-LytA | pET28a::his-lytA KanR, CmR | Philippe et al., 2015 |

| pET28-His-LytAE87Q | pET28a::his-lytAE87A KanR, CmR | This work |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| FORoJB1 | ggctatgggcttgatgagttc To amplify lytA::cat cassette |

This work |

| FORoJB2 | gcatcaaggtatccatcattcc To amplify lytA::cat cassette |

This work |

| FORoJB3 | actgtctttcccagcttcgg amplification upstream of the adr gene |

This work |

| REVoJB6 | acctgccaagttacctgtcg amplification downstream of the adr gene |

This work |

| REVoJB7 | ttagatccggatccctcgagttttgatttaaccggcttgtcttgag Construction of adr-sfGFPop |

This work |

| FORoJB8 | atggatgaattgtacaaataactc aag aca agccggttaaatc Construction of adr-sfGFPop |

This work |

| FORoJB9 | ctcgagggatccggatctaaaggtgaagagttgttt sfGFPop amplification |

This work |

| REVoJB10 | tttgtacaattcatccatacc sfGFPop amplification |

This work |

| REVoJB35 | taaccggcttgtcttacgagtttattcttcctttcattgtac Construction of adr::Δadr |

This work |

| FORoJB36 | gaagaataaactcgtaagacaagccggttaaatcaaaataac Construction of adr::Δadr |

This work |

| FORoJB57 | cgcgcgcgcatgcgcattaaatggttttccttgattaggattatag Construction of pJBadr |

This work |

| REVoJB58 | gcgcgtacgttattttgatttaaccggcttgtcttgagctgt Construction of pJBadr |

This work |

| FORoMJ129 | gatagcgccagttccgatga Construction of pgdA::kan-rpsl |

This work |

| FORoMJ62 | ggttgaatggctttcaatcagttgaaccgctgcataggtctcagc insertion of E87Q mutation in the pET28-His-LytA plasmid |

This work |

| REVoMJ63 | gctgagacctatgcagcggttcaactgattgaaagccattcaacc insertion of E87Q mutation in the pET28-His-LytA plasmid |

This work |

| FORoMJ130 | ttgattgaccgcaggaacga Construction of pgdA::kan-rpsl |

This work |

| FORoMJ142 | cattaaaaatcaaacggatctgccacgtcctagtctac Construction of pgdA::kan-rpsl |

This work |

| FORoMJ143 | aggggcccaggtctcagctgtactatagtcgtgatg Construction of pgdA::kan-rpsl |

This work |

| FORoMJ42 | cctatccgcctcttgcaagc amplification upstream of the ftsZ gene for ftsZ-kan-rpsl and ftsZ-mKate amplification |

Jacq et al., 2015 |

| FORoMJ47 | cttttaaagacatggttctctcctac amplification downstream of the ftsZ gene for ftsZ-kan-rpsl and ftsZ-mKate amplification |

Jacq et al., 2015 |

| P1 | ccgtttgatttttaatggataatg Kan-rpsl amplification |

This work |

| P2 | agagacctgggcccctttcc Kan-rpsl amplification |

This work |

| F1rpsL1 | ggtggttgtatttctgttgttgggt Forward rpsL1 amplification |

This work |

| R1rpsL1 | aactgggacttggtagttagaaccac Reverse rpsL1 amplification |

This work |

Amp, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Kan, kanamycin; Tet, tetracycline; Str, streptomycin.

Protein expression and purification

Strain BL21(DE3) Rosetta pLysS Rare (CmR) of E. coli was transformed with the plasmid pET28-His-LytA (KanR) or pET28-His-LytAE87Q (KanR). Cells were grown in Luria Bertani medium and protein expression was induced at OD595nm 0.6 with 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside) at 25°C overnight. Cells from 2-litres cultures were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 50 ml of a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete EDTA free, Sigma-Aldrich) and lyzed using a Microfluidize M-110P (Microfluidics). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (20 min at 39,191 × g at 4°C) and loaded onto a 10-ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) column (Qiagen). His-LytA proteins were eluted with a 25 mM to 500 mM imidazole gradient. Pooled fractions were concentrated and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex S75 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 150 mM NaCl.

Growth conditions, media, and transformation

Liquid cultures of S. pneumoniae strains were grown at 37°C/5%CO2 in C medium supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (Lacks and Hotchkiss, 1960) (CY) or in Todd Hewitt medium (TH; BD Sciences). For strains harboring a zinc-inducible plasmid, CY was supplemented with 0.15 mM ZnCl2 to induce protein expression. For transformation, about 250 ng of DNA was added to cells treated with synthetic competence stimulating peptide 1 in TH medium at pH 8.0 supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2. Cells were grown for 2 h at 37°C/5%CO2, and transformants were selected on Columbia (BD Sciences) blood (4%) agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotics (streptomycin 400 μg/ml, kanamycin 300 μg/ml, chloramphenicol 4.5 μg/ml).

Continuous growth was followed by inoculating 3 ml of CY medium in 24-wells plates, which were sealed and incubated at 37°C in a FLUOstar plate reader (BMG Labtech) equipped with a 595-nm filter. The OD595 was recorded every 10 to 20 min after shaking. Each point was done in triplicate. LytA sensitivity was determined by adding recombinant His-LytA at 10μg/mL either at OD595nm 0.3–0.4 or during the entire culture period. The latter condition was also used to evaluate the lysozyme sensitivity added at the final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Penicillin sensitivity was determined by adding 4 or 8 ng/ml to CY medium.

For labeling of newly synthesized peptidoglycan, cells were grown in CY at OD595nm 0.4 at 37°C/5%CO2, pelleted at room temperature for 2 min at 4500 g, resuspended and incubated for 3 min in CY supplemented with 2 mM HADA (Kuru et al., 2012). After two washes in CY to discard unbound dye, cells were resuspended into CY and immediately observed.

Fluorescence microscopy image acquisition and analysis

Cells were grown at 37°C/5%CO2 in CY to OD595nm 0.3, transferred to microscope slides, and observed at 37°C on an Olympus BX61 microscope equipped with a UPFLN 100 O-2PH/1.3 objective and a QImaging Retiga-SRV 1394 cooled charge-coupled-device camera. Image acquisition was performed using the software packages Volocity. Images were analyzed using the open-source softwares MicrobeTracker (Sliusarenko et al., 2011) and Oufti (Paintdakhi et al., 2016) and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS5 and Image J. Demographs integrate the signal values in each cell. The cells were sorted by their length value and the fluorescence values were plotted as a heat map.

Time-lapse microscopy using agarose pad was performed as follows. A glycerol stock of adr-sfGFPop FtsZ-mKate2 strain was inoculated in 5 ml of CY medium and grown to OD595nm of 0.1. An agarose pad containing CY medium and 1.2% low-melting agarose was prepared on a microscopy slide. A volume of 2.5 μl of culture was loaded on the agarose pad, a coverslip was mounted and the samples were observed. Images were acquired every 3 min or 6 mi min during 1 hour using an automated inverted epifluorescence microscope Nikon TiE/B equipped with the “perfect focus system” (PFS, Nikon), a phase contrast objective (CFI Plan Apo Lambda DM 100X, NA1.45), a Semrock filter set for GFP (Ex: 482BP35; DM: 506; Em: 536BP40) and mCherry (Ex: 562BP40; DM: 593; Em: 640BP75), a LED light source (Spectra X Light Engine, Lumencor), a cCMOS camera (Neo sCMOS, Andor) and a chamber thermostated at 37°C. Fluorescence images were capturated and processed using Nis-Elements AR software (Nikon). GFP fluorescence images were false colored green and overlaid on phase contrast images.

Electron microscopy

For high pressure freezing and sectioning, cells were grown in 40 ml of CY at 37°C CO2 to OD595nm 0.3–0.4, recombinant His-LytA was added at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, and incubation was pursued for 7 min. Cells were centrifuged at 4500 g for 5 min. A pellet volume of 1.4 μl was dispensed on the 200-μm side of a type A 3-mm gold platelet (Leica Microsystems), covered with the flat side of a type B 3-mm aluminum platelet (Leica Microsystems), and was vitrified by high-pressure freezing using an HPM100 system (Leica Microsystems). Next, the samples were freeze substituted at −90°C for 80 h in acetone supplemented with 1% OsO4 and warmed up slowly (1°C/h) to −60°C in an automated freeze substitution device (AFS2; Leica Microsystems). After 8 to 12 h, the temperature was raised (1°C/h) to −30°C, and the samples were kept at this temperature for another 8 to 12 h before a step for 1h at 0°C, cooled down to 30°C and then rinsed 4 times in pure acetone. The samples were then infiltrated with gradually increasing concentrations of Agar Low Viscosity Resin (LVR; Agar Scientific) in acetone (1:2, 1:1, 2:1 [vol/vol], and pure) for 2 to 3 h while raising the temperature to 20°C. Pure LVR was added at room temperature. After polymerization 24h at 60°C, 70 to 200-nm sections were obtained using an ultra-microtome UC7 (Leica Microsystems) and an Ultra 35° diamond knife (DiATOME) and were collected on formvar-carbon-coated 100-mesh copper or nickel grids. The thin sections were post-stained for 10 min with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate, rinsed, and incubated for 5 min with lead citrate. Digital images were obtained using a Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTwin microscope (FEI) operating at 120 kV with an Orius SC1000 CCD camera (Gatan).

For negative staining, cells were grown in CY medium until OD595nm 0.3 and incubated or not with LytA at 5 μg/ml during 20 min at 37°C/5% CO2. Cell lysis was stopped by the addition of glutaraldehyde at a final concentration of 2%. Cells were centrifuged 10 min at 4500g, resuspended in 100μL of PBS 2% glutaraldehyde and incubated for 1h at RT. The fixed cells were washed three times and resuspended in 50μL of water. Whole cells observation was made using the mica-carbon flotation technique on phosphotungstate (PTA) 2%. Digital images were obtained using a Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTwin microscope (FEI) operating at 120 kV with an Orius SC1000 CCD Camera (Gatan).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work used the platforms of the Grenoble Instruct centre (ISBG; UMS 3518 CNRS-CEA-UGA-EMBL) with support from FRISBI (ANR-10-INSB-05-02) and GRAL (ANRS-10-LABX-49-01) within the Grenoble Partnership for Structural Biology (PSB). The electron microscopy facility is supported by the Rhône-Alpes Region, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM), the fonds FEDER, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique (CEA), the University of Grenoble Alpes (UGA), the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) and the GIS-Infrastructures en Biologie Santé et Agronomie (IBISA). J.B. received a PhD fellowship from the French Ministry of Education and Research.

References

- Bera A, Herbert S, Jakob A, Vollmer W, Götz F. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:778–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard E, Rolain T, Courtin P, Guillot A, Langella P, Hols P, et al. Characterization of O-acetylation of N-acetylglucosamine: a novel structural variation of bacterial peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:23950–23958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.241414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard E, Rolain T, David B, André G, Dupres V, Dufrêne YF, et al. Dual role for the O-acetyltransferase OatA in peptidoglycan modification and control of cell septation in Lactobacillus plantarum. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair DE, Schüttelkopf AW, MacRae JI, van Aalten DM. Structure and metal-dependent mechanism of peptidoglycan deacetylase, a streptococcal virulence factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15429–15434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504339102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake C, Koening D, Mair G, North A. Structure of an hen egg-white lysozyme. A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 Å resolution. Nature. 1965;206:757–761. doi: 10.1038/206757a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Santa Maria JP, Jr, Walker S. Wall teichoic acids of Gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013;67:313–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert L, Michiels CW. Lysozymes in the animal kingdom. J Biosci. 2010;35:127–160. doi: 10.1007/s12038-010-0015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisóstomo MI, Vollmer W, Kharat AS, Inhülsen S, Gehre F, Buckenmaier S, et al. Attenuation of penicillin resistance in a peptidoglycan O-acetyl transferase mutant of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1497–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammeyer T, Tinnefield P. Engineered fluorescence proteins illuminate the bacterial periplasm. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2012;3:e201210013. doi: 10.5936/csbj.201210013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KM, Weiser JN. Modifications of the peptidoglycan backbone help bacteria to establish infection. Infect Immun. 2011;79:562–570. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00651-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. Using superfolder green fluorescent protein for periplasmic protein localization studies. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4984–4987. doi: 10.1128/JB.00315-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty TJ. Peptidoglycan biosynthesis in Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains sensitive and intrinsically resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:429–435. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.429-435.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty TJ. Involvement of a change in penicillin target and peptidoglycan structure in low-level resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:90–95. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt A, Wu LJ, Errington J, Vollmer W, Veening JW. Cellular localization of choline-utilization proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae using novel fluorescent reporter systems. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan AJF, Biboy J, van’t Veer I, Breukink E, Vollmer W. Activities and regulation of peptidoglycan synthases. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2015;370:20150031. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami K, Guyet A, Kawai Y, Devi J, Wu LJ, Allenby N, et al. RodA as the missing glycosyltransferase in Bacillus subtilis and antibiotic discovery for the peptidoglycan polymerase pathway. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:16253. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleurie A, Lesterlin C, Manuse S, Zhao C, Cluzel C, Lavergne JP, et al. MapZ marks the division sites and positions FtsZ rings in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nature. 2014a;516:259–262. doi: 10.1038/nature13966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleurie A, Manuse S, Zhao C, Campo N, Cluzel C, Lavergne JP, et al. Interplay of the serine/threonine-kinase StkP and the paralogs DivIVA and GpsB in pneumococcal cell elongation and division. PLoS Genet. 2014b;10:e1004275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard LV, Gooder H. Specificity of the autolysin of Streptococcus (Diplococcus) pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:796–804. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.796-804.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata T, Watanabe A, Kusumoto M, Akiba M. Peptidoglycan acetylation of Campylobacter jejuni is essential for maintaining cell wall integrity and colonization in chicken intestines. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:6284–6290. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02068-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacq M, Adam V, Bourgeois D, Moriscot C, Di Guilmi AM, Vernet T, et al. Remodeling of the Z-ring nanostructure during Streptococcus pneumoniae cell cycle revealed by photoactivated localization microscopy. mBio. 2015;6(4):e01108–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01108-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuru E, Velocity Hughes H, Brown PJ, Hall E, Tekkam S, Cava F, et al. In situ probing of newly synthesized peptidoglycan in live bacteria with fluorescent D-amino acids. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:12519–12523. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaberki MH, Pfeffer J, Clarke AJ, Dworkin J. O-Acetylation of peptidoglycan is required for proper cell separation and S-layer anchoring in Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5278–5288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.183236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacks S, Hotchkiss KD. A study of the genetic material determining an enzyme in Pneumococcus. Biochim Biophy Acta. 1960;39:508–518. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land AD, Tsui HCT, Kocaoglu O, Vella SA, Shaw SL, Keen SK, et al. Requirement of essential Pbp2x and GpsB for septal ring closure in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:939–955. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massida O, Novakova L, Vollmer W. From models to pathogens: how much have we learned about Streptococcus pneumoniae cell division? Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:3133–3157. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteyn BS, Karimova G, Fenton AK, Gazi AD, West N, Touqui L, et al. ZapE is a novel cell division protein interacting with FtsZ and modulating the Z-ring dynamics. mBio. 2014;5(2):e00022–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00022-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin HH, Gmeiner J. Modification of peptidoglycan structure by penicillin action in cell walls of Proteus mirabilis. Eur J Biochem. 1979;95:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb12988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeske AJ, Riley EP, Robins WP, Uehara T, Mekalanos JJ, Kahne D, et al. SEDS proteins are a widespread family of bacterial cell wall polymerases. Nature. 2016;537:634–638. doi: 10.1038/nature19331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellroth P, Daniels R, Eberhardt A, Rönnlund D, Blom H, Widengren J, et al. LytA, major autolysin of Streptococcus pneumoniae, requires access to nascent peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11018–11029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlot C, Zapun A, Dideberg O, Vernet T. Growth and division of Streptococcus pneumoniae: localization of the high molecular weight penicillin-binding proteins during the cell cycle. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:845–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlot C, Bayle L, Jacq M, Fleurie A, Tourcier G, Galisson F, et al. Interaction of Penicillin-Binding Protein 2x and Ser/Thr protein kinase StkP, two key players in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 morphogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:88–102. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan PJ, Clarke AJ. O-acetylation of peptidoglycan in gram-negative bacteria: identification and characterization of peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13264–13273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan PJ, Clarke AJ. O-acetylation peptidoglycan: controlling the activity of bacterial autolysins and lytic enzymes of innate immune systems. Int J Biochem Cell Biology. 2011;43:1655–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan PJ, Sychantha D, Clarke AJ. Chemical biology of peptidoglycan acetylation and deacetylation. Bioorg Chem. 2014;54:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik J, Kern I, Lurz R, Hakenbeck R. Mutational analysis of the Streptococcus pneumoniae bimodular class A penicillin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3852–3856. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3852-3856.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paintdakhi A, Parry B, Campos M, Irnov I, Elf J, Surovtsev I, et al. Oufti: an integrated software package for high-accuracy, high-throughput quantitative microscopy analysis. Mol Microbiol. 2016;99:767–777. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliero E, Dublet B, Frehel C, Dideberg O, Vernet T, Di Guilmi AM. The inactivation of a new peptidoglycan hydrolase Pmp23 leads to abnormal septum formation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. The Open Microbiol J. 2008;2:107–114. doi: 10.2174/1874285800802010107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pédelacq JD, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:79–88. doi: 10.1038/nbt1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer JM, Strating H, Weadge JT, Clarke AJ. Peptidoglycan O-acetylation and autolysin profile of Enterococcus faecalis in the viable but nonculturable state. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:902–908. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.902-908.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe J, Gallet B, Morlot C, Denapaite D, Hakenbeck R, Chen Y, et al. Mechanism of β-lactam action in Streptococcus pneumoniae: the piperacillin paradox. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:609–621. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04283-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandalova T, Lee M, Henriques-Normark B, Hesek D, Mobashery S, Mellroth P, et al. The crystal structure of the major pneumococcal autolysin LytA in complex with a large peptidoglycan fragment reveals the pivotal role of glycans for lytic activity. Mol Microbiol. 2016;101:954–967. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage E, Kerff F, Terrak M, Ayala JA, Charlier P. The penicillin-binding proteins: structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:234–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage E, Terrak M. Glycosyltransferases and Transpeptidases/Penicillin-Binding Proteins: valuable targets for new antibacterials. Antibiotics. 2016;5:12. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics5010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster C, Dobrinski B, Hakenbeck R. Unusual septum formation in Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants with an alteration in the d,d-carboxypeptidase penicillin-binding protein 3. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6499–6505. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6499-6505.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sido T, Johannsen L, Labischinski H. Penicillin-induced changes in the cell wall composition of Staphylococcus aureus before the onset of bacteriolysis. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:73–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00249181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliusarenko O, Heinritz J, Emonet T, Jacobs-Wagner C. High-throughput, subpixel precision analysis of bacterial morphogenesis and intracellular spatio-temporal dynamics. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:612–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Blackman SA, Foster SJ. Autolysins of Bacillus subtilis: multiple enzymes with multiple functions. Microbiology. 2000;146:249–262. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-2-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung CK, Li H, Claverys JP, Morrison DA. An rpsL cassette, Janus, for gene replacement through negative selection in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5190–5196. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.5190-5196.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasz A. Biological consequences of the replacement of choline by ethanolamine in the cell wall of pneumococcus: chain formation, loss of transformability, and loss of autolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:86–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasz A, Waks S. Mechanism of action of penicillin: triggering of the pneumococcal autolytic enzyme by inhibitors of cell wall synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:4162–4166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.10.4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui T, Boersma MJ, Vella SA, Kocaoglu O, Kuru E, Peceny JK, et al. Pbp2x localizes separately from Pbp2b and other peptidoglycan synthesis proteins during later stages of cell division of Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:21–40. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocadlo DJ, Davies GJ, Laine R, Withers SG. Catalysis by hen egg-white lysozyme proceeds via a covalent intermediate. Nature. 2001;412:835–838. doi: 10.1038/35090602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:259–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer W. Structural variation in the glycan strands of bacterial peptidoglycan. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008a;32:287–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weadge JT, Pfeffer JM, Clarke AJ. Identification of a new family of enzymes with potential O-acetylpeptidoglycan esterase activity in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weadge JT, Clarke AJ. Identification and characterization of O-acetylpeptidoglycan esterase: a novel enzyme discovered in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Biochemistry. 2006;45:839–851. doi: 10.1021/bi051679s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.