Abstract

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a devastating neurodevelopmental disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in the X-linked methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (Mecp2) gene. GABAergic dysfunction has been implicated contributing to the respiratory dysfunction, one major clinical feature of RTT. The nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) is the first central site integrating respiratory sensory information that can change the nature of the reflex output. We hypothesized that deficiency in Mecp2 gene reduces GABAergic neurotransmission in the NTS. Using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in NTS slices, we measured spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs), miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs), NTS-evoked IPSCs (eIPSCs), and GABAA receptor (GABAA-R) agonist-induced responses. Compared to those from wild-type mice, NTS neurons from Mecp2-null mice had significantly (p<0.05) reduced sIPSC amplitude, sIPSC frequency, and mIPSC amplitude but not mIPSC frequency. Mecp2-null mice also had decreased eIPSC amplitude with no change in paired-pulse ratio. The data suggest reduced synaptic receptor-mediated phasic GABA transmission in Mecp2-null mice. In contrast, muscimol (GABAA-R agonist, 0.3 – 100 μM) and THIP (selective extrasynaptic GABAA-R agonist, 5 μM) induced significantly greater current response in Mecp2-null mice, suggesting increased extrasynaptic receptors. Using qPCR, we found a 2.5 fold increase in the delta subunit of the GABAA-Rs in the NTS in Mecp2-null mice, consistent with increased extrasynaptic receptors. As the NTS was recently found required for respiratory pathology in RTT, our results provide a mechanism for NTS dysfunction which involves shifting the balance of synaptic/extrasynaptic receptors in favor of extrasynaptic site, providing a target for boosting GABAergic inhibition in RTT.

Keywords: NTS, GABA, Rett syndrome, Extrasynaptic receptors, patch clamp

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT), caused by loss-of-function mutations in the X-linked gene encoding the epigenetic regulator Mecp2 (methyl-CpG-binding protein 2), is a devastating neurodevelopmental disorder that primarily affects young girls (Ellaway and Christodoulou, 1999; Chahrour and Zoghbi, 2007). Although it is a rare disorder, RTT has recently become a prototypical model for studying synaptic dysfunction in neurological disorders (Chahrour and Zoghbi, 2007). RTT is also categorized as a syndromic autism spectrum disorder and shares important pathogenic pathways with autism (Levitt and Campbell, 2009; Gonzales, 2010). A major cause of morbidity and mortality in RTT is dysfunctional respiratory control due to Mecp2 deficiency (Katz et al., 2009). Conclusions from genetic, neurochemical, and pharmacological studies support that depressed GABAergic neurotransmission in the brainstem contributes to RTT breathing abnormalities (Chao et al., 2010; Ure et al., 2016). Augmenting GABAergic neurotransmission has been shown to improve the respiratory phenotype in RTT mouse models and to prolong survival (Abdala et al., 2010; Voituron and Hilaire, 2011; Bittolo et al., 2016).

Respiratory neurons reside mainly in two regions of the brainstem: the dorsal respiratory group in the nucleus tractus solitaries (NTS) and the ventral respiratory group in the ventrolateral medulla (Bonham, 1995). Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter involved in the central generation of respiratory rhythm while GABA acting on GABAA receptors (GABAA-Rs) provides phasic waves of inhibition to shape the pattern of the respiratory motor output (Bonham, 1995). Wasserman and colleagues showed that blocking GABA reuptake with nipecotic acid in the NTS increased inspiratory duration that frequently culminates in apneustic breathing (Wasserman et al., 2002). They further showed that GABAB receptors mediated the increased inspiratory duration and GABAA-Rs mediated the apnea effects. Importantly, in Mecp2-null mice, selective recovery of Mecp2 expression in the HoxA4 domain, which includes caudal parts of NTS and ventral respiratory column, was sufficient to restore normal respiratory rhythm and prevent apnea (Huang et al., 2016), suggesting an important role of the NTS in RTT pathophysiology. Thus, we focused on NTS GABAA-R dysfunction in a Mecp2-null mouse model in order to provide a pathophysiological basis for abnormal respiratory regulation in RTT.

Materials and Methods

Mouse model of RTT

All experimental protocols were carried out with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California Davis. Mecp2tm1.1Bird/+ mice, which originated from Dr. Adrian Bird's laboratory (Guy et al., 2001), were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Mice were mated with C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories). Mice were genotyped to determine the Mecp2 deletion according to the protocol provided by the Jackson Laboratory. The Mecp2-null males 7 to 10 weeks old were used in the present study as a mouse model of RTT, while their male littermates served as the WT control. The sex of the pups was determined using primers for the Sry gene on Y chromosome, which were 5′-TGG GAC TGG TGA CAA TTG TC-3′ and 5′- GAG TAC AGG TGT GCA GCT CT-3′.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

Brain slices containing the NTS were obtained as previously described (Chen et al., 2009; Sekizawa et al., 2012; Sekizawa et al., 2013). The mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. The brain was rapidly removed and submerged in ice-cold (< 4°C) high-sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) that contained (mM): 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 220 sucrose and 2 CaCl2, pH 7.4 when continuously bubbled with 95% O2/ 5% CO2. Brainstem transverse slices (250 μm thick) were cut with the Vibratome 1000 (Technical Products International, St. Louis, MO). After incubation for 45 min at 35°C in high-sucrose aCSF, the slices were placed in normal aCSF that contained (mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 glucose and 2 CaCl2, pH 7.4 when continuously bubbled with 95% O2 / 5% CO2. During the experiments a single slice was transferred to the recording chamber, held in place with a nylon mesh, and continuously perfused with oxygenated aCSF at a rate of ∼3 ml/min. Borosilicate glass electrodes (BF150-86-10, Sutter Instrumnt, Novato, CA) were filled with a CsCl solution containing (in mM): 140 CsCl, 5 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 3 K-ATP, 0.2 Na-GTP, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 5 QX314. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. The seal resistance was >1 GΩ. The series resistance was no greater than 15 MΩ and not different (t-test, p > 0.05) between wild type (13.2 ± 0.5 MΩ, mean ± SEM) and Mecp2-null (13.6 ± 0.6 MΩ, mean ± SEM) mice. Recordings were made with a MultiClamp 700B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Whole-cell currents were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz with a DigiData 1440A interface (Molecular Devices).

The neurons were voltage clamped at -60 mV. All experiments were performed in the presence of ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxo-benzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide disodium salt (NBQX, 10 μM) and DL-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP-5, 50 μM) to isolate the inhibitory currents from excitatory currents.

To determine the inhibitory synaptic input, spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were recorded for 6 min. The sIPSCs in the last 3 min of the recording were used for data analysis. To isolate the action potential-independent synaptic inputs, miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) were recorded in the presence of the sodium channel blocker, tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM). To stimulate GABA release from local inhibitory neurons in the NTS for evoked-IPSCs (eIPSCs), a bipolar tungsten electrode (1 μM tips separated by 80 μM) was placed in the intermediate NTS ipsilateral and medial to the recording site. We used the minimal intensity (4 – 8 V, 0.1 ms duration) required to consistently evoke IPSCs. There was no difference (t-test, p > 0.05) in the intensities used to evoke IPSCs in WT (6.6 ± 0.3 V, mean ± SEM) and Mecp2-null mice (6.7 ± 0.4 V, mean ± SEM). The averaged distance between the stimulating electrode and the recorded neurons was 361 ± 5.71 μm (mean ± SEM; ranging from 300 μm to 420 μm). Pairs of NTS stimuli with an inter-pulse interval of 60 ms were delivered at 0.1 Hz to determine paired-pulse ratios (Chen and Bonham, 2005). In separate neurons, muscimol (30 s perfusion, 0.3 – 100 μm)-or THIP (5 μM)-induced whole-cell currents were recorded. GABAAR agonist, Muscimol, was applied in the bath for 30 sec, after a stable baseline was recorded. To evaluate changes in GABAergic tonic current, 10 minutes were allowed in order for the response to stabilize, and the recorded baseline activity for approximaly 3 minutes follow by the bath perfusion for 4 minutes of the GABAaR partial agonist THIP (5 μM) to increase GABAergic tonic current. After THIP perfusion, GABAAR antagonist bicuculline (30 μM) was added to block both phasic and tonic currents. To confirm that the recorded currents were IPSCs and agonist-induced whole cell currents were recorded before and after perfusion with the GABAA-R antagonist bicuculline (30 μM) in some neurons.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Brainstem slices (300 μm) containing the NTS were obtained as described above. Bilateral punches of the NTS were obtained with a 0.5 mm biopsy punch (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). RNA purity and concentrations were assessed by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm, and 280 nm using a NanoDrop 2000C Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The primer sequences used to quantify GABAA-R subunit mRNAs are listed in Table 1. For β-actin, we used the commercially available primer set Mouse ACTB (Actin, Beta) Endogenous Control FAM Dye/MGB Probe, Non-Primer Limited (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Gene expression was normalized to an endogenous reference gene, β-actin. Data were analyzed with the 2-ΔCt method. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Table 1.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Forward Primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse Primer (3′ → 5′) |

|---|---|---|

| α1 | GAGCACACTGTCGGGAGGAA | GCTCTCCCAAACCTGGTCTC |

| α2 | TGACTCCGTTCAGGTTGCTC | TGCAAGGCAGATAGGTCTGA |

| α3 | CTCTCTGCTTCGGGGAAGTG | ATTCCCCTTGGCTAGTGGTT |

| α4 | AGTCAGTGGAGGTGCCAAAG | GGTGGTCATCGTGAGGACTG |

| α5 | CCCCTGAAATTTGGCAGTAT | CAGGTGGAAGTGAGCAGTCA |

| α6 | GACTTTGCCCATCGTTCC | TGCAAAAGCTACTGGGAAGAG |

| β1 | GGTTTGTTGTGCACACAGCTCC | ATGCTGGCGACATCGATCCGC |

| β2 | GCTGGTGAGGAAATCTCGGTCCC | CATGCGCACGGCGTACCAAA |

| β3 | GAGCGTAAACGACCCCGGGAA | GGGACCCCCGAAGTCGGGTCT |

| γ1 | ATCCACTCTCATTCCCATGAACAGC | ACAGAAAAAGCTAGTACAGTCTTTGC |

| γ2 | ACTTCTGGTGACTATGTGGTGAT | GGCAGGAACAGCATCCTTATTG |

| γ3 | ATTACATCCAGATTCCACAAGATG | CACAGGTGTCCTCAAATTCCT |

| δ | TGGCCAGCATTGACCATATC | CCAGCTCTGATGCAGGAACA |

Statistical analysis

The sIPSC and mIPSC events were detected with MiniAnalysis software (Synaptosoft, Fort Lee, NJ). The accuracy of detection was confirmed by visual inspection. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). A t-test was used to compare between wild type and Mecp2-null mice for the following measurements: sIPSC/mIPSC frequency and amplitude, eIPSC amplitude, decay time constant, and paired-pulse ratio. A two-way repeated ANOVA was used to compare THIP-and muscimol-induced responses, followed by Fisher's LSD test for pairwise comparison when appropriate. Relative cDNA levels for the target genes were analyzed by the 2-ΔΔCt method using Actb (β-actin) as the internal control for normalization (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). A t-test was used to compare between WT and Mecp2-null mice. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Chemicals

Isoflurane was obtained from Piramal (Bethlehem, PA). QX 314 was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, United Kingdom). TTX, bicuculline, NBQX, and AP-5 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All other chemicals were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Reverse Transcription Supermix, and SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

Results

Whole-cell patch-clamp data were obtained from 67 neurons in 28 wild type (WT) mice and 63 neurons in 24 Mecp2-null mice. There was no difference (t-test, p > 0.05) in cell capacitance (17.9 ± 1.5 pF vs 18.5 ± 1.1 pF, wild type vs Mecp2-null, respectively). There was also no difference (t-test, p > 0.05) in whole cell input resistance (698 ± 42 MΩ vs. 660 ± 51 MΩ, wild type vs. Mecp2-null, respectively).

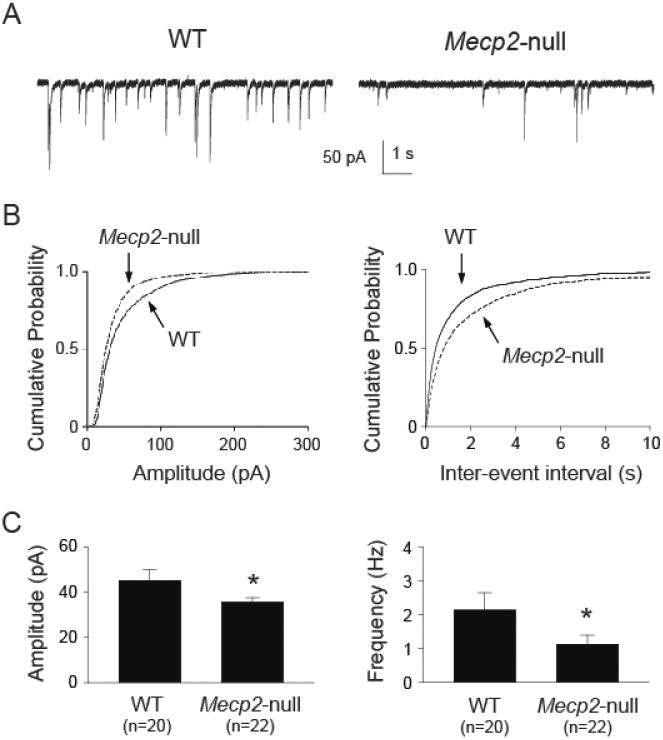

Reduced sIPSC amplitude and frequency in NTS neurons in Mecp2-null mice

Example recordings of sIPSCs from the NTS neurons are shown in figure 1A. The group data of Mecp2-null neurons, compared to WT neurons, showed a leftward shift in the cumulative probability of the sIPSC amplitude (figure 1B, left) with a rightward shift in the inter-event intervals (figure 1B, right). The mean sIPSC amplitude (figure 1C, left) was significantly lower (t-test, p < 0.05) in Mecp2-null mice than that in WT mice. The mean frequency (figure 1C, right) was also significantly lower (t-test, p < 0.05) in Mecp2-null mice than that in WT mice. There was no significant difference (t-test, p > 0.05) in IPSC decay time (19 ± 1 ms vs. 21 ± 2 ms, WT vs. Mecp2-null, respectively). The data suggest that Mecp2-null mice had reduced synaptically-mediated phasic inhibitory inputs in the NTS.

Figure 1.

Mecp2-null mice had reduced sIPSC amplitude and frequency in the NTS. A. Example traces of sIPSC recorded from one wild type (WT) and one Mecp2-null mouse. B. Cumulative probability plot from all recorded neurons showing a leftward shift in sIPSC amplitude (left), suggesting reduced sIPSC amplitude in Mecp2-null mice. There was a rightward shift in inter-event interval cumulative plot (right), suggesting a reduction in sIPSC frequency. C. Group data showing reduced mean sIPSC amplitude (left) and frequency (right). *, p < 0.05 Mecp2-null vs. WT (t-test).

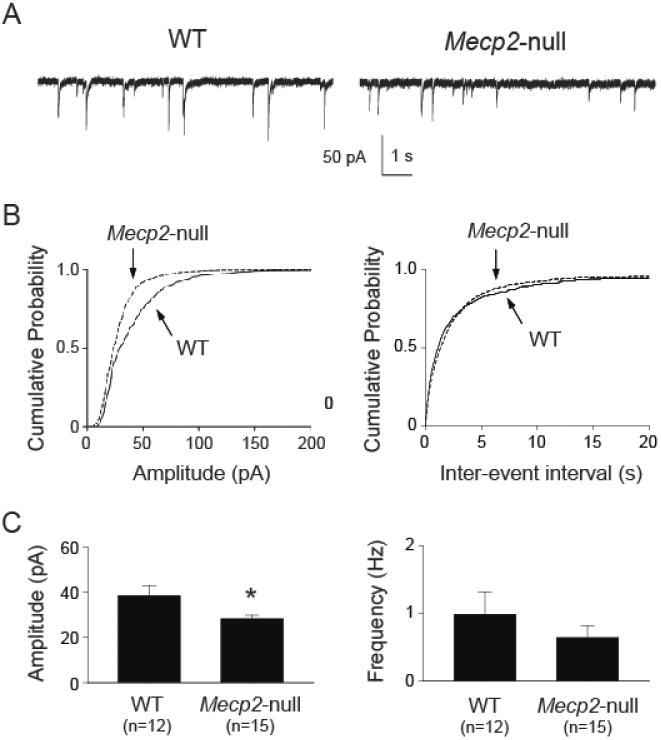

Reduced mIPSC amplitude but not frequency in Mecp2-null mice

The reduced sIPSC frequency could be mediated by changes in the action potential-mediated neurotransmitter release and/or action potential-independent release. We recorded mIPSCs in the presence of TTX (1 μM) to eliminate action potential-dependent synaptic events. Figure 2 shows example recordings of mIPSCs from NTS neurons. Similar to sIPSCs, the group data of Mecp2-null neurons, compared to WT neurons, showed a leftward shift in the cumulative probability of the mIPSC amplitude (figure 2B, left). However, in contrast to sIPSCs, there was no difference in the cumulative probability of the inter-event interval (figure 2B, right). The mean mIPSC amplitude (figure 2C, left) was significantly lower (t-test, p < 0.05) in Mecp2-null mice than that in WT mice. The mean frequency (figure 2C, right) was not different between WT and Mecp2-null mice. There was also no difference (t-test, p > 0.05) in decay time (22 ± 2 ms vs. 23 ± 1 ms, wild type vs. Mecp2-null, respectively). These mIPSC events were completely blocked by 30 μM of bicuculline (data not shown), confirming that these are GABAA-R mediated synaptic events. Together, our sIPSC and mIPSC data suggest that 1) the reduced sIPSC event frequency was due to reduced action potential-dependent GABA release (reduced activity of GABAergic interneurons); and 2) Mecp2-null mice had reduced phasic synaptic GABAergic transmission in the NTS.

Figure 2.

Mecp2-null mice had reduced mIPSC amplitude but not frequency in the NTS. A. Example traces of mIPSC recorded from one wild type (WT) and one Mecp2-null mouse. B. Cumulative probability plot from all recorded neurons showing a leftward shift in mIPSC amplitude (left), suggesting reduced sIPSC amplitude in Mecp2-null mice. There was no difference in inter-event interval cumulative plot (right). C. Group data showing reduced mean sIPSC amplitude (left) but not frequency (right). *, p < 0.05 Mecp2-null vs. WT (t-test).

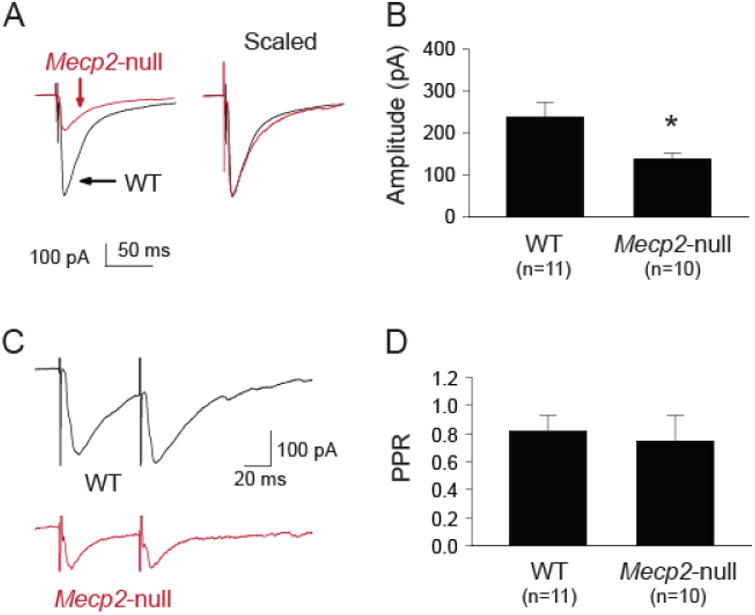

Reduced eIPSC amplitudes but not the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) in Mecp2-null mice

As shown in figure 3A & B the NTS-evoked IPSC amplitude was significantly smaller in neurons from Mecp2-null mice. The time courses of eIPSCs from both groups appear to be similar after scaling the IPSCs to the same peak amplitude (figure 3A, right). There was no difference (t-test, p > 0.05) in decay time constants (21.6 ± 2.6 ms vs. 23.5 ± 2.8 ms, wild type vs. Mecp2-null, respectively). The reduced eIPSC amplitude was not associated with a change in the PPR (60 ms interval, figure 3C, D). The data suggest that the reduced phasic synaptic inhibition is likely mediated by postsynaptic mechanism(s) and not a change in presynaptic release probability.

Figure 3.

Mecp2-null mice had reduced eIPSC amplitude but not paired-pulse ratio in the NTS. A. Example traces of NTS-evoked IPCSs from one WT and one Mecp2-null mouse. Left, traces shown as their relative amplitude; Right, traces scaled to the same peak amplitude. B. Group data showing that the eIPSC amplitude was significantly smaller in neurons from the Mecp2-null mice. C. Example traces of NTS-evoked paired IPSCs from one WT and one Mecp2-null mouse. D. Group data showing similar paired-pulse ratio (60 ms inter stimulus interval) between the two groups, suggesting a postsynaptic mechanism mediating the reduced IPSC amplitude in Mecp2-null mice. *, p < 0.05 Mecp2-null vs. WT (t-test).

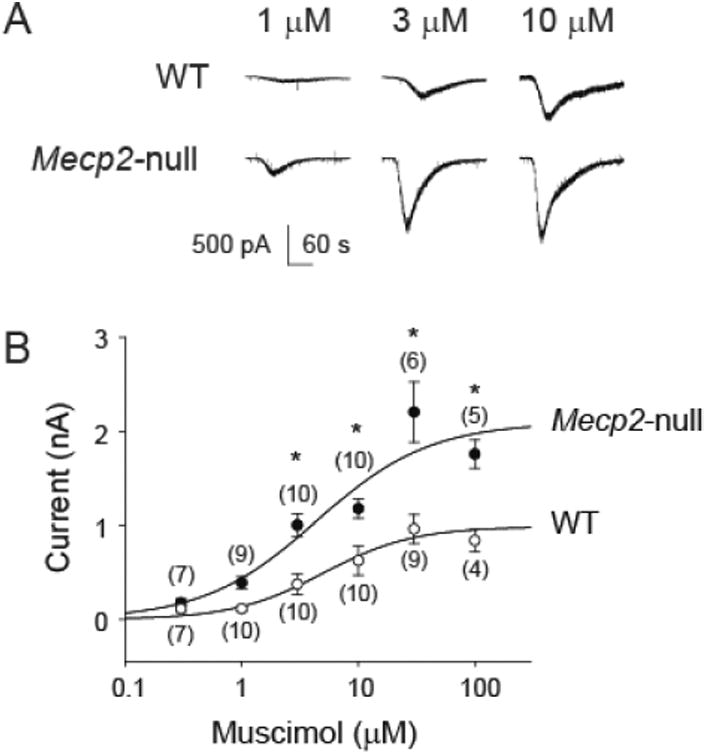

Enhanced GABAA-R agonist-induced currents in Mecp2-null mice

In the presence of NBQX, AP-5, and TTX, exogenous application of a GABAA-R agonist, muscimol, induces concentration-dependent inward currents. Figure 4A shows example traces of muscimol-induced currents from one WT and one Mecp2-null mouse. Interestingly, in contrast to reduced phasic synaptic transmission, the amplitudes of muscimol-induced currents were larger in the Mecp2-null mouse. The group data (figure 4B) confirmed that Mecp2-null mice had a significantly greater response to GABAA-R activation with muscimol (two-way ANOVA: p<0.05, genotype; p<0.05, concentration; p<0.05, interaction).

Figure 4.

Mecp2-null mice had larger muscimol-induced currents in the NTS. A. Example traces of muscimol-induced concentration-dependent current responses from one WT and one Mecp2-null mouse. Black bar indicates application of Muscimol. B. Group data of concentration-dependent response showing enhanced muscimol-induced currents in neurons recorded from the Mecp2-null mice (two-way ANOVA: p < 0.05, genotype; p < 0.05, concentration; p < 0.05, interaction). Numbers in parentheses indicate number of neurons. *, p < 0.05, Mecp2-null vs. FA, Fisher's LSD post-hoc test.

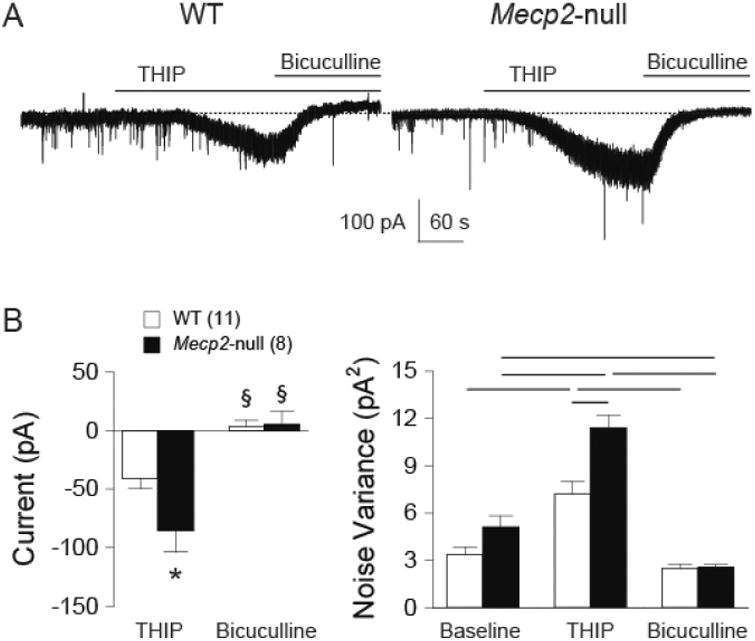

Given that exogenous application of the GABAA-R agonist activated both synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA-Rs, we tested the agonist-induced response with THIP, a selective extrasynaptic GABAA-R agonist. Figure 5A shows example traces of whole cell current response to application of THIP (5 μM) in the absence and presence of bicuculline (30 μM). Example traces show that THIP induced a greater inward current in the neuron from the Mecp2-null mouse. Bicuculline blocked the THIP-induced currents, in addition to blocking phasic synaptic events, indicating that the THIP-induced currents were mediated by GABAA-Rs. The group data confirmed that THIP-induced a greater current in Mecp2-null mice (Figure 5B, left) and bicuculline blocked the THIP-induced current in both WT and Mecp2-null mice (two-way ANOVA: p<0.05, genotype; p<0.05, concentration; p<0.05, interaction). THIP also significantly increased the noise variance in both groups (figure 5B right, two-way ANOVA: p>0.05, genotype; p<0.05, concentration; p<0.05, interaction). The increase in the noise variance was significantly greater (t-test, p < 0.05) in the Mecp2-null mice (3.8 ± 0.7 vs. 6.1 ± 1.2, WT vs. Mecp2-null, respectively). The data suggest an increase in extrasynaptic GABAA-R function in the Mecp2-null mice. Furthermore, bicuculline significantly reduced the noise variance (compared to the baseline) in Mecp2-null mice but not in WT mice, suggesting an elevated tonic extrasynaptic GABAA-R function in Mecp2-null mice.

Figure 5.

Mecp2-null mice had larger THIP-induced currents in the NTS. A. Example traces of THIP-induced current responses before and during bicuculline perfusion from one WT and one Mecp2-null mouse. B. Group data of changes in current from baseline (before THIP application) showing enhanced THIP-induced currents in neurons recorded from the Mecp2-null mice (Fisher's LSD post-hoc test: *, p < 0.05 WT vs. Mecp2-null; §, p < 0.05 THIP vs. Bicuculline within the same genotype). C. Group data of noise variance before THIP application (Baseline), during THIP, and during THIP + bicuculline (bicuculline). THIP significantly increased noise variance in both groups. Each line on top indicates p < 0.05 between the two bars, Fisher's LSD post-hoc test.

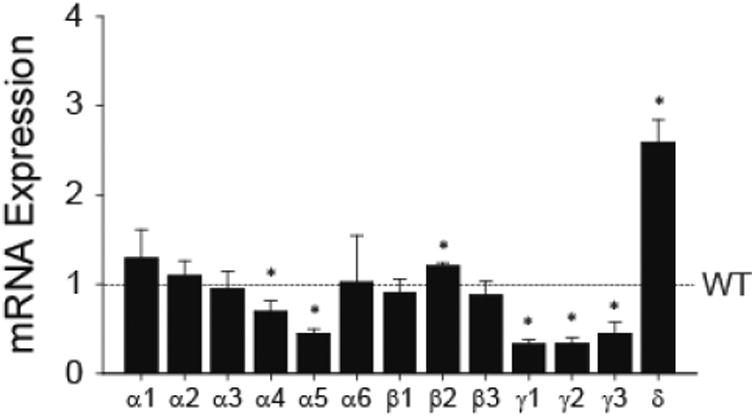

Differential expression of GABAA-R subunit transcripts in Mecp2-null mice

The subunit compositions of extrasynaptic GABAA-Rs are different from those of synaptic GABAA-Rs. Because deficiency of Mecp2, functioning as an epigenetic modulator, changes cellular transcriptomic landscape (Pohodich and Zoghbi, 2015), we hypothesized altered NTS gene expression in RTT shifting toward extrasynaptic GABAA-R subunits. Figure 6 shows the transcript levels of NTS GABAA-R subunits of Mecp2-null mice, expressed as fold change from those of WT mice. Mecp2-null NTS had significantly lower α4 and α5 subunits (t-test, p<0.05). Importantly, all three γ subunits were significantly reduced while the δsubunit, found exclusively in extrasynaptic site, increased by more than 2 folds (t-test, p<0.05). The data are consistent with the electrophysiology data showing an increase in extrasynaptic GABAA-R function and suggest that there is a shift in GABAA-Rs from synaptic to extrasynaptic site in Mecp2-null mice.

Figure 6.

GABAA-R subunit mRNA expression level in the NTS. All data were normalized to expression level of the WT (dotted line). N = 4 in each group. *, p < 0.05 vs. WT (t-test on data before normalizing to WT).

Discussion

In this study, we sought to identify anatomy- and physiology-informed GABAergic mechanisms leading to dysfunctional respiratory control in RTT. We focused on the NTS, a medulla nucleus containing gateway synapses that integrate sensory input to coordinate reflex output of respiratory control (Andresen and Kunze, 1994; Joad et al., 2004; Bonham et al., 2006a; Bonham et al., 2006b). We found reduced sIPSC and mIPSC amplitudes in NTS neurons in Mecp2-null mice, suggesting reduced phasic synaptic GABAergic transmission. Spontaneous IPSC frequency, but not mIPSC frequency, was reduced in Mecp2-null mice, reflecting a general reduction of the activity of GABAergic neurons. Because eIPSC amplitude was also reduced in the Mecp2-null NTS neurons, but there was no changes in PPR, we concluded that the reduced GABAergic neurotransmission was mainly due to postsynaptic mechanism(s). Interestingly, despite this postsynaptic deficit, Mecp2-null neurons showed enhanced responses to muscimol, which activates both synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA-Rs, and THIP, which selectively activates extrasynaptic GABAA-Rs. These results, together with the altered gene expression pattern of GABAA-R subunits (significant reductions of all three γ subunits and a more than two fold increase of the δ subunit) in the Mecp2-null NTS, suggest a shift in GABAA-Rs from synaptic to extrasynaptic loci. Taken together, our data suggest that NTS GABAergic dysfunction in RTT is mainly due to postsynaptic mechanisms that may involve an imbalance between phasic (synaptic) and tonic (extrasynaptic) inhibitory tones. Moreover, there is reduced GABA release due to reduced GABAergic neuronal activities, but not due to reduced presynaptic GABA release probability.

Our results complement the finding of Kline et al. (Kline et al., 2010), who studied EPSCs in the NTS, although they used the Mecp2tm1-1Jae model (Chen et al., 2001), which differs from the complete knockout Mecp2tm1.1Bir model used in our study in that the Mecp2tm1-1Jae allele still produces a truncated and modified protein product. They found that the amplitudes of spontaneous, miniature, and evoked EPSCs in NTS neurons were all significantly increased in Mecp2tm1-1Jae/Y mice. This was unaffected by blockade of inhibitory GABA currents, suggesting independent Mecp2-regulated mechanisms enhancing the excitatory tones. Together, the data suggest that there is a shift in the balance of excitation and inhibition towards excitatory tone in the NTS.

Overall, the consequence of Mecp2 deficiency appears to be an aggravated imbalance between synaptic excitation and inhibition (Dani et al., 2005; Chao et al., 2007; Medrihan et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; Chao et al., 2010; Banerjee et al., 2016). The notion of pathological disruption of excitatory/inhibitory homeostasis resulting in behavior symptoms in RTT is further supported by studies of mouse models with selective knockout of Mecp2 in glutamatergic neurons (Meng et al., 2016), GABAergic neurons (Chao et al., 2010; Banerjee et al., 2016), or selective rescue of GABA/glycine inhibitory neurons (Ure et al., 2016). In the NTS, this shift in synaptic excitability towards excitation could contribute to altered respiratory regulation in RTT, including apneustic breathing (Bonham, 1995; Burton and Kazemi, 2000).

Although changes in excitatory and inhibitory transmissions are commonly detected in RTT, the specific changes appear to be age- and brain region-dependent, perhaps not surprisingly given the time-dependent progression of the disease and functions of different brain regions. For example, Medrihan et al. showed that, in neonates (p7), there was an increased excitatory transmission coupled with a reduction in the number of GABA synapses in ventrolateral medulla, an area of the reticular brain stem formation including the pre-Bötzinger complex responsible for generating the respiratory rhythm (Medrihan et al., 2008). Abdala et al. showed reduced GABAergic terminal projections in the Kölliker–Fuse nucleus in the dorsolateral pons, and administration of a drug that augments endogenous GABA localized to this region reduced the incidence of apnea and the respiratory irregularity of RTT female mice (Abdala et al., 2016). In contrast, our data suggest that NTS neurons in Mecp2-null mice have reduced phasic GABA transmission mainly due to postsynaptic receptor mechanism(s). Similarly, Jin and colleagues showed a reduction in sIPSC frequency and amplitude – but not before the age of 3 weeks in locus coeruleus (LC), a pontine nucleus that provide major norepinephrine projections (Jin et al., 2013).

In addition to changes in reduction in phasic synaptic transmission, we detected an increase in the extrasynaptic GABAA-R that was not seen in p7 in Medrihan's study, suggesting that enhanced tonic inhibition maybe a beneficial mechanism to compensate for the falling phasic GABAergic neurotransmission. Parallel to our finding in the NTS, Jiang and colleagues showed augmentations of tonic currents and noise variance by THIP in LC neurons, with a greater degree of increase in Mecp2-null neurons than in WT neurons (Zhong et al., 2015). Also similar to our findings in the NTS, they found, in the LC, a reduction in the expression of GABAA-R α5 subunit and a close to two fold increase in δ, the major subunit component of extrasynaptic GABAa-Rs (Nusser et al., 1998). The changes in subunit expression may contribute to enhanced tonic GABA currents in Mecp2-null neurons. We further found that all three γ subunits were significantly reduced in Mecp2-null NTS neurons; among which γ2 is well-known to be involved in direct GABAergic synaptic transmission (Farrant and Nusser, 2005).

The variations of reported GABAergic deficits in different brainstem nuclei suggest that local dynamics of Mecp2-regulated GABAA-R subunit expression may contribute to various reorganizations and synaptic/extrasynaptic distributions of GABAA-R variants, a mechanism requiring further studies. First, alterations in the tonic GABAA-R-mediated conductance have been implicated in disruptions in network dynamics associated with some neurological disorders (Brickley and Mody, 2012). Is enhanced tonic inhibition truly a beneficial compensatory mechanism or is it aggravating the network dysfunction underlying seizure and respiratory dysfunction in RTT? Second, the NTS receives and integrates sensory afferents from multiple tissues, including those carrying information about blood pressure. Does the enhanced tonic inhibition in the NTS alter other autonomic functions such as blood pressure regulation? Third, the observation of enhanced tonic inhibition in at least two distinct brainstem structures (NTS and LC) could be therapeutically significant. Is it generalizable beyond the two brainstem nuclei? Such questions are highly important as enhancement of GABAergic neurotransmission is currently considered a promising therapy for RTT but approaches for effective long-term GABAergic inhibition remain to be found. If tonic inhibition is beneficial, the effect can be augmented by compounds selectively enhancing the tonic inhibition, which in principle will work well since our data show that extrasynaptic GABAA-R species underlying tonic inhibition appear to be over-expressed and active in RTT. In this regard, Zhong et al. showed that early-life exposure of Mecp2-null mice to THIP alleviated breathing abnormalities (Zhong et al., 2016), suggesting that enhancing tonic inhibition could be a feasible therapeutic approach for RTT, at least for the purpose of mitigating breathing abnormalities, a major morbidity.

In conclusion, the data reported here show a reduced GABAergic synaptic receptor-mediated phasic transmission and an increased GABAergic extrasynaptic transmission. This study demonstrates an imbalance in NTS GABA transmission that could provide a target for respiratory dysfunction in RTT.

Highlights.

Mecp2-null mice have reduced receptor-mediated phasic inhibitory input in the NTS

Mecp2-null mice have increased extra-synaptic inhibitory transmission in the NTS

Mecp2-null mice have 2.5 fold increase in the delta subunit of the GABAAR in the NTS

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grants 1R01 HD064817 (to L-W. J.) and R01 HL091763-01A1 (to C-Y. C.), and a HeART award #2905 from the International Rett Syndrome Foundation (to L-W. J.), and in part by the NIH grant U54 HD079125 to the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: C-Y.C., L-W.J., M.R., C-C.L. and I.M. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. J.DL and Y-C.L. performed the experiments and data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdala AP, Dutschmann M, Bissonnette JM, Paton JF. Correction of respiratory disorders in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18208–18213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012104107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdala AP, Toward MA, Dutschmann M, Bissonnette JM, Paton JF. Deficiency of GABAergic synaptic inhibition in the Kolliker-Fuse area underlies respiratory dysrhythmia in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. The Journal of physiology. 2016;594:223–237. doi: 10.1113/JP270966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Nucleus tractus solitarius--gateway to neural circulatory control. Annual Review of Physiology. 1994;56:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Rikhye RV, Breton-Provencher V, Tang X, Li C, Li K, Runyan CA, Fu Z, Jaenisch R, Sur M. Jointly reduced inhibition and excitation underlies circuit-wide changes in cortical processing in Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E7287–E7296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615330113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittolo T, Raminelli CA, Deiana C, Baj G, Vaghi V, Ferrazzo S, Bernareggi A, Tongiorgi E. Pharmacological treatment with mirtazapine rescues cortical atrophy and respiratory deficits in MeCP2 null mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19796. doi: 10.1038/srep19796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham AC. Neurotransmitters in the CNS control of breathing. Respiration physiology. 1995;101:219–230. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00045-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham AC, Chen CY, Sekizawa S, Joad JP. Plasticity in the nucleus tractus solitarius and its influence on lung and airway reflexes. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2006a;101:322–327. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00143.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham AC, Sekizawa S, Chen CY, Joad JP. Plasticity of brainstem mechanisms of cough. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006b;152:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley SG, Mody I. Extrasynaptic GABA(A) Receptors: Their Function in the CNS and Implications for Disease. Neuron. 2012;73:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MD, Kazemi H. Neurotransmitters in central respiratory control. Respiration physiology. 2000;122:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HT, Zoghbi HY, Rosenmund C. MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron. 2007;56:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HT, Chen H, Samaco RC, Xue M, Chahrour M, Yoo J, Neul JL, Gong S, Lu HC, Heintz N, Ekker M, Rubenstein JL, Noebels JL, Rosenmund C, Zoghbi HY. Dysfunction in GABA signalling mediates autism-like stereotypies and Rett syndrome phenotypes. Nature. 2010;468:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nature09582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Bonham AC. Glutamate suppresses GABA release via presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors at baroreceptor neurones in rats. The Journal of physiology. 2005;562:535–551. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Bechtold AG, Tabor J, Bonham AC. Exercise Reduces GABA Synaptic Input onto Nucleus Tractus Solitarii Baroreceptor Second-Order Neurons via NK1 Receptor Internalization in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2754–2761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4413-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RZ, Akbarian S, Tudor M, Jaenisch R. Deficiency of methyl-CpG binding protein-2 in CNS neurons results in a Rett-like phenotype in mice. Nature genetics. 2001;27:327–331. doi: 10.1038/85906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani VS, Chang Q, Maffei A, Turrigiano GG, Jaenisch R, Nelson SB. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12560–12565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellaway C, Christodoulou J. Rett syndrome: clinical update and review of recent genetic advances. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35:419–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.355403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales ML, LaSalle JM. The Role of MeCP2 in Brain Development and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2010;12:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy J, Hendrich B, Holmes M, Martin JE, Bird A. A mouse Mecp2-null mutation causes neurological symptoms that mimic Rett syndrome. Nature genetics. 2001;27:322–326. doi: 10.1038/85899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TW, Kochukov MY, Ward CS, Merritt J, Thomas K, Nguyen T, Arenkiel BR, Neul JL. Progressive Changes in a Distributed Neural Circuit Underlie Breathing Abnormalities in Mice Lacking MeCP2. J Neurosci. 2016;36:5572–5586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2330-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Cui N, Zhong W, Jin XT, Jiang C. GABAergic synaptic inputs of locus coeruleus neurons in wild-type and Mecp2-null mice. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2013;304:C844–857. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00399.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joad JP, Munch PA, Bric JM, Evans SJ, Pinkerton KE, Chen CY, Bonham AC. Passive smoke effects on cough and airways in young guinea pigs: role of brainstem substance P. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2004;169:499–504. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1139OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DM, Dutschmann M, Ramirez JM, Hilaire G. Breathing disorders in Rett syndrome: progressive neurochemical dysfunction in the respiratory network after birth. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2009;168:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Ogier M, Kunze DL, Katz DM. Exogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic dysfunction in Mecp2-null mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5303–5310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5503-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P, Campbell DB. The genetic and neurobiologic compass points toward common signaling dysfunctions in autism spectrum disorders. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:747–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI37934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrihan L, Tantalaki E, Aramuni G, Sargsyan V, Dudanova I, Missler M, Zhang W. Early defects of GABAergic synapses in the brain stem of a MeCP2 mouse model of Rett syndrome. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:112–121. doi: 10.1152/jn.00826.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XL, Wang W, Lu H, He LJ, Chen W, Chao ES, Fiorotto ML, Tang B, Herrera JA, Seymour ML, Neul JL, Pereira FA, Tang JR, Xue MS, Zoghbi HY. Manipulations of MeCP2 in glutamatergic neurons highlight their contributions to Rett and other neurological disorders. eLife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. Segregation of different GABAA receptors to synaptic and extrasynaptic membranes of cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1693–1703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohodich AE, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome: disruption of epigenetic control of postnatal neurological functions. Human molecular genetics. 2015;24:R10–16. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekizawa SI, Horowitz JM, Horwitz BA, Chen CY. Realignment of signal processing within a sensory brainstem nucleus as brain temperature declines in the Syrian hamster, a hibernating species. J Comp Physiol A. 2012;198:267–282. doi: 10.1007/s00359-011-0706-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekizawa SI, Horwitz BA, Horowitz JM, Chen CY. Protection of signal processing at low temperature in baroreceptive neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius of Syrian hamsters, a hibernating species. Am J Physiol-Reg I. 2013;305:R1153–R1162. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00165.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ure K, Lui H, Wang W, Ito-Ishida A, Wu ZY, He LJ, Sztainberg Y, Chen W, Tang JR, Zoghbi HY. Restoration of Mecp2 expression in GABAergic neurons is sufficient to rescue multiple disease features in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. eLife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voituron N, Hilaire G. The benzodiazepine Midazolam mitigates the breathing defects of Mecp2-deficient mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;177:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman AM, Ferreira M, Jr, Sahibzada N, Hernandez YM, Gillis RA. GABA-mediated neurotransmission in the ventrolateral NTS plays a role in respiratory regulation in the rat. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2002;283:R1423–1441. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00488.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, He J, Jugloff DG, Eubanks JH. The MeCP2-null mouse hippocampus displays altered basal inhibitory rhythms and is prone to hyperexcitability. Hippocampus. 2008;18:294–309. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, Johnson CM, Wu Y, Cui N, Xing H, Zhang S, Jiang C. Effects of early-life exposure to THIP on phenotype development in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders. 2016;8:37. doi: 10.1186/s11689-016-9169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, Cui N, Jin X, Oginsky MF, Wu Y, Zhang S, Bondy B, Johnson CM, Jiang C. Methyl CpG Binding Protein 2 Gene Disruption Augments Tonic Currents of gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Receptors in Locus Coeruleus Neurons: IMPACT ON NEURONAL EXCITABILITY AND BREATHING. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:18400–18411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.650465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]