Abstract

The Dependent Coverage Expansion (DCE), a component of the Affordable Care Act, required private health insurance policies that cover dependents to offer coverage for policyholders’ children through age 25. This review summarizes peer-reviewed research on the impact of the DCE on the chain of consequences through which it could affect public health. Specifically, we examine the impact of the DCE on insurance coverage, access to care, utilization of care, and health status. All studies find that the DCE increased insurance coverage, but evidence regarding downstream impacts is inconsistent. There is evidence that the DCE reduced high out-of-pocket expenditures and frequent emergency room visits and increased behavioral health treatment. Evidence regarding the impact of the DCE on health is sparse but suggestive of positive impacts on self-rated health and health behavior. Inferences regarding the public health impact of the DCE await studies with greater methodological diversity and longer follow-up periods.

Keywords: Dependent Care Expansion, Young Adults, Insurance Coverage, Public Health, Dependent Coverage Expansion, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Health Insurance, Public Health Impacts

Historically the age group most likely to lack health insurance coverage in the U.S. has been young adults, too old to qualify for insurance available nearly universally to minors and too young to have high rates of employment at large employers that provide employer-based insurance (Collins, Garber, & Robertson, 2011). For instance, according to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), in 2010 the proportion of individuals with no health insurance coverage was 7.8% among those under 18 years of age, 31.5% among those 18 to 24, and 28.3% among those 25 to 34(Cohen, Ward, & Schiller, 2011). The young adult age group also tends to be in relatively good health, a fact likely to contribute to their reticence to purchase health insurance (Cantiello, Fottler, Oetjen, & Zhang, 2011). However, access to health care during young adulthood is important for preventive care that reduces the likelihood of later-life chronic illness and treatment for disorders that reach their highest incidence levels during this age, such as psychiatric and substance use disorders, (R. Kessler et al., 2005).

Over the past several decades, state governments have attempted to improve access to health care for young adults through dependent coverage expansion (DCE) policies. These policies extend eligibility for dependent care coverage beyond age 18, the traditional eligibility cutoff. By 2010, 31 states had passed DCE legislation requiring private insurance policies which cover dependents include coverage for some adult children of beneficiaries beyond age 18 (Cantor, Belloff, Monheit, DeLia, & Koller, 2012). However, state DCE laws were limited in that they varied in the age range for eligibility, excluded some categories of adult children, such as those who are married, and did not apply to large self-insured employers who are exempt from such state regulation and account for about half of the private employer-based insurance market nationally (Cantor, Belloff, et al., 2012). In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) established a national DCE by requiring private insurance plans that cover dependents to offer that coverage through age 26 without exclusions common in the state laws.

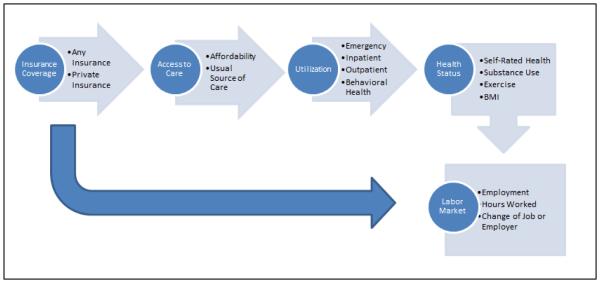

Evidence regarding the impact of the state DCE laws suggests that though they had some effects on the type of insurance held by young adults, they did not reduce rates of uninsurance (Cantor, Belloff, et al., 2012; Monheit, Cantor, DeLia, & Belloff, 2011). In contrast, initial studies of the ACA’s DCE provision, found evidence that the policy resulted in more young adults being insured (B. D. Sommers, 2012). However, the direct effect of the DCE on insurance coverage is only the first of several steps in the hypothesized beneficial cascade of social consequences that could produce its intended positive effects. As shown in Figure 1, the increase in insurance coverage is intended to positively affect access to care, utilization of care, and ultimately health status. Insurance coverage may lead not only to increases in utilization of some types of health care services, but shifts from more expensive acute care to less expensive preventive care. In addition, the increase in insurance coverage may affect labor market decisions indirectly, both through the effect on health directly and more commonly through removing health insurance coverage as a factor from considering employment alternatives, i.e. by removing ‘job lock’. With insurance that is not connected to employment (i.e. less ‘job lock’) young adults may be more likely to change employers, work fewer hours, or leave the workforce. Perhaps most importantly, the DCE provides an opportunity to study the extent to which change in access to insurance affects the health status of young adults, a difficult to target demographic group.

FIGURE 1.

POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF THE DCE ON YOUNG ADULTS

With the goal of advancing a more comprehensive picture of the policy’s effects, this review summarizes existing empirical research on each step in the chain of causation linking the ACA’s DCE provision with these downstream consequences for the health of young adults. Research on each link in the chain is important for evaluating the overall effect and for identifying specific barriers that may continue to limit the policy’s impact. Understanding the overall picture of the impact of the policy is important for understanding how health insurance coverage affects the health and health related behaviors of young adults.

METHODS

Literature Search

We searched bibliographic databases and reference lists of relevant papers for peer-reviewed empirical studies of the impact of the ACA’s DCE on insurance coverage, health care access, utilization, health status (including health behaviors), and labor market activity. The search covered the time period from September 2010 through January of 2016 and included EBSCOHOST databases (Academic Search Complete, Business Source Complete, EconLit), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Pubmed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search terms included ‘young adult’, ‘adolescent’, ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’, ‘dependent coverage’, and ‘health reform’. A full description of the search strategy for each database is available from the authors. The search produced a total of 1,023 papers. The large majority of papers did not include empirical assessments of the impact of the DCE. Review of titles and abstracts by the first author of this study reduced this to a set of 25 papers reporting empirical assessments of the impact of the DCE on a downstream outcome. Some papers reported impacts on multiple outcomes. The final set of papers included 14 examining insurance coverage, 6 examining other measures of access to health care such as having a usual source of care, 12 examining health care utilization, including emergency department (ED) visits (6 papers), hospitalizations (5 papers), and outpatient preventive or behavioral care (9 papers), 5 examining health status, including self-reported physical and/or mental health (5 papers), and 2 reporting labor market behavior. Papers reporting analyses of more than one dataset or more than one subsample of a dataset are listed separately in the tables, but counted as a single study.

Data Abstraction

An initial review of the manuscripts revealed that the overwhelming majority (24 out of 25) use a difference-in-differences (DD) method for estimating the impact of the DCE, in which change in the targeted age group is compared with concurrent change in a control age group. Papers were reviewed in depth independently by two authors with conflicts resolved after re-review by the lead author. The following were abstracted from each paper: the age groups (and corresponding sample sizes) representing the intervention and control populations, the time periods representing the pre- and post-implementation periods, the data source, analytic approach, outcome measures, and the findings concerning the impact of the DCE. Papers are listed once for each separate data source from which they derived estimates of the impact of the DCE. All outcomes reported in the papers were abstracted, including those for which no effect of the DCE was found.

RESULTS

We summarize results for each of the outcome domains following a consistent format below.

Health Insurance Coverage

Fourteen papers examine the impact of the DCE on health insurance coverage among individuals age 19-25 (Table 1). The papers analyze repeated cross-sectional data from six national surveys of the U.S. general population and one national dataset of emergency room visits. All of the papers use a DD approach to estimating the effect of the DCE, though they vary slightly in the age ranges and the time periods examined. Twelve of the fourteen studies compare individuals in the full target age range of the policy, age 19 to 25, with an older group of individuals outside of the target age range, ranging from 26 to 34 years of age. The specific ages included in comparison group vary in minor ways across studies, and one study includes a younger (age 16-18) comparison group as well as an older comparison group. Some studies omit 26 year olds from the comparison group, presumably because they may have been previously affected by the policy (e.g. someone who was 26 in 2012 would have been in the target age group in 2011). Two studies select more restricted age ranges to represent intervention and control groups. These studies select a narrow age band at the upper end of the range affected by the DCE and a narrow age band at the lower end of the control ages in order to reduce age-related historical trends that may confound the difference in differences model. The most extreme application of this approach uses 25 year olds as the intervention group and 27 year olds as controls(Slusky, 2015).

Table 1.

Studies of the impact of the Federal DCE on Insurance Coverage

| Paper | Intervention | Control | Time Period | Data Source |

Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group |

Sample Size |

Age Group |

Sample Size |

Pre-DCE | Post- DCE |

|||

| (Akosa Antwi et al., 2013) | 19-25 | 16,803 | 16- 18, 27-29 |

18,059 | 8/2008- 2/2010 |

9/2010- 11/2011 |

SIPP | Any Insurance + Private Insurance + Public Insurance □ |

| (Barbaresco et al., 2015) | 23-25 | 49,502 | 27-29 | 68,892 | 1/2007- 9/2010 |

10/2010- 12/2013 |

BRFSS | Any Insurance + |

| (Cantor, Monheit, DeLia, & Lloyd, 2012) | 19- 251 |

85,158 | 27-30 | 71,203 | 2004- 2009 |

2010 | CPS | Any Insurance + Private Insurance + Public Insurance □ |

| (Chua & Sommers, 2014) | 19-25 | 26,453 | 26-34 | 34,052 | 2002- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | Any Insurance + |

| (Jhamb et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 21,993 | 27-33 | 26,750 | 2005- 2009 |

2011- 2013 |

NHIS | Any Insurance + |

| (Kotagal et al., 2014) | 19-25 | Not reported |

26 - 34 |

Not reported |

2009 | 2012 | BRFSS | Any Insurance + |

| (O'Hara & Brault, 2013) | 19-25 | 1,474,9102 | 26-29 | 794,1822 | 2008- 9/2010 |

9/2010- 2011 |

ACS | Any Insurance + Private Insurance + |

| (John W. Scott et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 246,2823 | 26-34 | 217,8863 | 2007- 2009 |

2011- 2012 |

NTDB | Any Insurance + |

| (J. W. Scott et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 529,844 | 27-34 | 484,974 | 2007- 2009 |

2011- 2012 |

NTDB | Any Insurance + |

| (Shane & Ayyagari, 2014) | 19-25 | 14,684 | 27-34 | 14,684 | 2008- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | Any Insurance + |

| (B. D. Sommers & Kronick, 2012) | 19-25 | 247, 370 | 26-34 | 247, 370 | 2005- 2009 |

2010 | CPS | Any Insurance + Private Insurance + |

| (Benjamin D. Sommers, Buchmueller, Decker, Carey, & Kronick, 2013) | 19-25 | 79,3612 | 26-34 | 37,1752 | 2005- 2010 |

9/2010- 9/2011 |

NHIS | Any Insurance + Private Insurance + |

| (Benjamin D. Sommers et al., 2013) | 19-25 | 173,4062 | 26-34 | 73,9642 | 2005- 8/2010 |

8/2010- 12/2010 |

CPS | Any Insurance + Private Insurance + |

| (Wallace & Sommers, 2015) | 19-25 | 142,356 | 26-34 | 314,610 | 1/2005- 3/2010 |

9/2010- 12/2012 |

BRFSS | Any Insurance + |

| (Slusky, 2015) | 25 | 21,6164 | 27 | 21,6164 | 2008- 2009 |

2011 | SIPP | Any Insurance + |

+=Statistically significant and positive DD estimate of effect of DCE on the outcome; □ = DD estimate of effect of DCE on the outcome is not statistically significant.

SIPP= Survey of Income and Program Participation; BRFSS= Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CPS= Current Population Survey; MEPS=Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHIS=National Health Interview Survey; ACS=American Community Survey; NTDB=National Trauma Data Bank

Full-time students age 19--22 excluded.

Estimate based on approximate percentage of total sample provided in paper.

Sample comprised of encounters, not individuals

Total sample size. Breakdown by intervention and control not given.

Despite the difference in the study age groups, the findings are remarkably consistent with all studies reporting a positive effect of the DCE on health insurance coverage. Results are also unanimous in finding a positive effect of the DCE on private insurance coverage (6 studies), the direct target of the policy, and no effect of the DCE on public insurance (2 studies), suggesting that gains in private insurance did not simply come from switching from public sources.

Access to Care

Six studies using data from three national surveys have examined measures of access to care (Table 2). All six studies used DD models. Four papers examine the impact of the DCE on out of pocket (OOP) expenditures on health care, all using the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS). Of these, three papers report significant reductions as a result of the DCE. One study found that the DCE reduced the probability of having more than $1500 of OOP expenditures in a year by over 50% (Busch, Golberstein, & Meara, 2014). The other study found that the DCE reduced average OOP expenditures by 18% and decreased the OOP share of total medical expenditures by 3.7% (Chua & Sommers, 2014). The third paper finds a reduction in the proportion of health care expenditures paid by patients OOP among people with behavioral health conditions(Ali, Chen, Mutter, Novak, & Mortensen, 2016).There is contrary evidence in a paper that reports no effect on the share of medical expenditures that are paid OOP, despite using the same dataset as other papers showing reductions in this same outcome (Chen, Bustamante, & Tom, 2015). The divergence in results may be due to the fact that the paper by Chen and colleagues excluded high cost outliers, i.e. those who may have gained the most from the policy, from the analysis. Notably, the paper by Ali and colleagues, which finds a reduction in the proportion of health expenditures paid OOP in a subsample with mental health problems, uses a model that accounts for the skewed distribution of the outcome without excluding individuals with extreme costs, a zero-or-one inflated regression.

Table 2.

Studies of the Impact of the Federal DCE on Access to Care

| Paper | Intervention | Control | Time Period | Data Source |

Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group |

Sample Size |

Age Group |

Sample Size |

Pre-DCE | Post- DCE |

|||

| (Ali et al., 2016) | 19-25 | 1,158 | 27-29 | 618 | 2008- 2009 |

2011- 2012 |

MEPS | Reduction in Proportion of Costs Paid OOP for Individuals with Behavioral Health Disorders |

| (Busch et al., 2014) | 19-25 | 141,596 | 26-29 | 84,368 | 2007- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | Reduction in High OOP Costs |

| (Chen et al., 2015) | 19-26 | 9,327 | 27-30 | 4,982 | 2008- 2009 |

2011- 2012 |

MEPS | No effect on OOP as share of total medical expenditure |

| (Chua & Sommers, 2014) | 19-25 | 26,453 | 26-34 | 34,052 | 2002- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | Reduction in Logged OOP expenditures; reduction in OOP as share of total medical expenditure |

| (Kotagal et al., 2014) | 19-25 | Not reported |

26-34 | Not reported |

2009 | 2012 | NHIS | No effect on being unable to afford prescriptions |

| (Kotagal et al., 2014) | 19-25 | Not reported |

26-34 | Not reported |

2009 | 2012 | BRFSS | Increase in having a usual source of care; No effect on being unable to see a Dr. due to cost |

| (Wallace & Sommers, 2015) | 19-25 | 142,356 | 26-34 | 314,610 | 1/2005- 3/2010 |

9/ 2010 - 12/2012 |

BRFSS | Decrease in being unable to see a Dr. due to cost; Increase in having a usual source of care |

MEPS= Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHIS=National Health Interview Survey; BRFSS= Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CPS= Current Population Survey;

Two papers using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) examined the impact of the DCE on respondent reports of having a usual source of care. The papers use different time periods to characterize pre- and post-DCE conditions, but both report significant increase in the proportion of young adults having a usual source of care, one finding an increase of 2.4% (Wallace & Sommers, 2015) and the other finding an increase of 2.8% (Kotagal, Carle, Kessler, & Flum, 2014). Two papers report impacts of the DCE on patient reports of being unable to afford medical care. A paper using data from the NHIS reports no effect of the DCE on affordability of medications, dental visits or physician visits (Kotagal et al., 2014). Two papers which assess the impact of the DCE on cost as a barrier to seeing a physician report divergent results despite using the same dataset, one finding no effect(Kotagal et al., 2014) and one finding a decrease of 1.9%(Wallace & Sommers, 2015). This divergence may be due to the fact that the paper reporting a significant impact of the DCE used data covering longer time periods for both the pre-DCE and the DCE time periods.

Healthcare Utilization

Fourteen papers examine impacts of the DCE on various aspects of utilization of health care. We separate these into studies of emergency department visits, hospital stays, and outpatient preventive and behavioral health visits. All but one of the 14 studies (Lau, Adams, Park, Boscardin, & Irwin, 2014) used a DD model. The exception assessed the extent to which secular change in utilization among young adults during the period of DCE implementation was mediated by concurrent change in insurance coverage. Mediation by change in insurance status was interpreted as evidence of an effect of the DCE.

Emergency Department (ED) Visits

Six papers examine the impact of the DCE on ED utilization, three using national or state level administrative records and three using national surveys (Table 3). The evidence from these studies is mixed. The three studies of administrative databases find that the DCE reduced the rate of ED visits in the population by about 1.5 visits per 1000 people. One study which examined psychiatric ED visits in California also found a reduction in the population rate attributable to the DCE. However, only one of these studies examined the likelihood that an individual will have one or more ED visits, and that study found no effect of the DCE. These findings suggest that the DCE may have reduced the frequency of ED use among users, but not the likelihood of becoming an ED user. Three studies of ED utilization in national survey data found no effects of the DCE, including one study which examined the number of visits per person. The most likely explanation for the divergent results is that the studies finding effects of the DCE use administrative databases while those that do not find effects use population surveys.

Table 3.

Studies of the Impact of the ACA DCE on ED Visits

| Paper | Intervention | Control | Time Period | Data Source | Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group |

Sample Size |

Age Group |

Sample Size |

Pre- DCE |

Post- DCE |

|||

| (Antwi, Moriya, Simon, & Sommers, 2015) | 19-25 | 12,309,0 03 ED Visits |

27-29 | 4,987,3 78 ED Visits |

2007- 2009 |

2011 | NEDS | Reduction in rate of ED visits |

| (Hernandez-Boussard, Burns, Wang, Baker, & Goldstein, 2014) | 19-25 | 5,684,71 4 ED Visits |

26-31 | 4,473,5 40 ED Visits |

9/2009- 8/2010 |

1/2011 - 12/201 1 |

State ED Databases from Florida, New York, and California |

Reduction in rate of ED visits. No effect on likelihood of using ER |

| (Golberstein et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 982,167 ED Visits |

26-29 | 595,683 ED Visits |

1/2005- 4/2010 |

9/2010- 12/201 1 |

California State ED Database |

Reduction in psychiatric emergency department visits |

| (Jhamb et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 21993 | 27-33 | 26750 | 2005- 2009 |

2011- 2013 |

NHIS | No effect on number of ER visits |

| (Chua & Sommers, 2014) | 19-25 | 26,453 | 26-34 | 34,052 | 2002- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | No effect on having an ER visit |

| (Chen et al., 2015) | 19-26 | 9,327 | 27-30 | 4,982 | 1/2008- 12/200 9 |

1/2011- 12/201 2 |

MEPS | No effect on having an ER visit |

NEDS=Nationwide Emergency Department Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; NHIS=National Health Interview Survey; MEPS=Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Hospital Stays

Five papers examine the impact of the DCE on hospital stays, three using administrative databases and two using MEPS survey data (Table 4). One of the studies of administrative data examined all medical hospitalizations (excluding pregnancies) (Akosa Antwi, Moriya, & Simon, 2015) and found that the DCE resulted in a 3.5% increase in hospitalizations. That study also found that the effect of the DCE on admissions was greater for psychiatric admissions, increasing admissions with psychiatric diagnoses by 9%. A study using two administrative databases found evidence that the DCE resulted in an increase in the likelihood of psychiatric admission by 1.4 admissions per 1,000 population in a national dataset but had no effect on psychiatric admissions in a dataset limited to California (Golberstein et al., 2015). Two studies of administrative databases examined intensity of care as measured by length of stay, number of procedures or total charges per stay during hospitalization and found no effects of the DCE (Akosa Antwi et al., 2015; John W. Scott et al., 2015). Neither of the two studies using MEPS data found any evidence of an effect of the DCE on the likelihood of hospitalization (Chen et al., 2015; Chua & Sommers, 2014). As with the studies of ED visits, the lack of significant findings in studies using survey data may result from small sample sizes in population surveys relative to the administrative databases. In addition, the DCE may have reduced repeat admissions, thereby reducing the population rate (admissions per person in the population) without reducing the likelihood that an individual would have an admission (individuals with one or more admissions as a proportion of the population).

Table 4.

Studies of the impact of the ACA DCE on inpatient care utilization

| Paper | Intervention | Control | Time Period | Data Source |

Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group |

Sample Size |

Age Group |

Sample Size |

Pre- DCE |

Post- DCE |

|||

| (Akosa Antwi et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 736,969 Admits |

27-29 | 377,345 Admits |

1/2007- 3/2010 |

9/2010- 12/2011 |

NIS | Increase in inpatient and psychiatric inpatient admission rates. No effect on intensity of inpatient treatment |

| (Golberstein et al., 2015) | 19-26 | 1,329,051 Admits |

26-29 | 807,452 Admits |

1/2005- 4/2010 |

1/2010- 12/2011 |

NIS | Increase in psychiatric admission rate |

| (Golberstein et al., 2015) | 19-26 | 150,010 Admits |

26-29 | 104,654 Admits |

1/2005- 4/2010 |

9/2010- 12/2011 |

California State Inpatient Database |

No effect on psychiatric admission rate |

| (John W. Scott et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 246,282 Admits |

26-34 | 217,886 Admits |

2007- 2009 |

2011- 2012 |

NTDB | No effect on length of post-ED ICU stay |

| (Chua & Sommers, 2014) | 19-25 | 26,453 | 26-34 | 34,052 | 2002- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | No effect on having one or more hospitalization |

| (Chen et al., 2015) | 19-26 | 9,327 | 27-30 | 4,982 | 1/2008- 12/2009 |

1/2011- 12/2012 |

MEPS | No effect on having one or more hospitalization |

NIS=National Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; NTDB=National Trauma Data Bank; MEPS=Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Outpatient Preventive and Behavioral Health Visits

Nine papers examine the impact of the DCE on utilization of preventive or behavioral health care, using data from four national surveys (Table 5). One of the papers used a method other than the DD approach used in the other papers(Lau, Adams, Park, et al., 2014). Seven of the studies examine whether the DCE increased the likelihood of having one or more outpatient medical visits or a physical exam, and all of these studies found no effect. However, the one study that examined the number of office visits found that the DCE increased the number of visits(Jhamb, Dave, & Colman, 2015). This study also used data covering a longer follow-up period than the studies with negative findings regarding the impact of the DCE on outpatient visits. One study found an increase in blood pressure measurement and another study found an increase in cholesterol screening. These two findings contrast with a larger number of studies of specific preventive procedures. Four studies found no effect of the DCE on flu shots and two studies found no effect of the DCE on PAP tests. The one paper to examine specialty behavioral health care found a 5.3% increase in the likelihood of using specialty mental health care by people with a probable mental illness, but no increase in use of substance disorder treatment by people with a substance use disorder.

Table 5.

Studies of the impact of the ACA DCE on outpatient preventive and behavioral health care

| Paper | Intervention | Control | Time Period | Data Source |

Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group |

Sample Size |

Age Group |

Sample Size |

Pre-DCE | Post-DCE | |||

| (Barbaresco et al., 2015) | 23-25 | 49,502 | 27-29 | 68,892 | 1/2007- 9/2010 |

10/2010- 12/2013 |

BRFSS | No effect on flu shot, physical exam or PAP test |

| (Chen et al., 2015) | 19-26 | 9,327 | 27-30 | 4,982 | 1/2008- 12/2009 |

1/2011- 12/2012 |

MEPS | No effect on having ≥1 physician visit |

| (Han, Yabroff, Robbins, Zheng, & Jamal, 2014) | 19-25 | 10,150 | 26-30 | 7,044 | 2009 | 2011- 2012 |

MEPS | Increase in blood pressure measurement. No effect on flu vaccination, PAP test, or physical exams |

| (Kotagal et al., 2014) | 19-25 | Not reported |

26-34 | Not reported |

2009 | 2012 | BRFSS | No effect on physical exam |

| (Kotagal et al., 2014) | 19-25 | Not reported |

26-34 | Not reported |

2009 | 2012 | NHIS | No effect on flu shot |

| (Jhamb et al., 2015) | 19-25 | 21,993 | 27-33 | 26,750 | 2005- 2009 |

2011- 2013 |

NHIS | Increase in number of Dr.’s office visits |

| (Lau, Adams, Park, et al., 2014) | 18-25 | 7,485 | No Control Age Group |

2009 | 2011 | MEPS | Increase in cholesterol screening. No effect on physical exam, blood pressure measurement or flu shot |

|

| (Wallace & Sommers, 2015) | 19-25 | 142,356 | 26-34 | 314,610 | 1/2005- 3/2010 |

9/2010- 12/2012 |

BRFSS | No effect on physical exam |

| (Chua & Sommers, 2014) | 19-25 | 26,453 | 26-34 | 34,052 | 2002- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | No effect on ≥1 outpatient or primary care visit |

| (Saloner & Le Cook, 2014) | 18-25 | 13,897 | 26-35 | Not reported |

2008- 2010 |

2011- 2012 |

NSDUH | Increase in use of any MH outpatient services. No effect on inpatient, outpatient or private MH care |

| (Saloner & Le Cook, 2014) | 18-25 | 14,705 | 26-35 | Not reported |

2008- 2010 |

2011- 2012 |

NSDUH | No effect on SA treatment of any kind |

BRFSS= Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; MEPS= Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHIS=National Health Interview Survey; NSDUH=National Survey of Drug Use and Health; MH=Mental Health; SA=Substance Abuse

Health Status

Five papers examined impacts of the DCE on self-rated health status using data from national surveys (Table 6). All used DD models. One of these five papers also examined additional health status outcomes which we discuss separately below (Barbaresco, Courtemanche, & Qi, 2015). Of the studies examining self-rated physical health, four of five found significant, positive effects of the DCE. However, the nature of these effects is complicated by differences in how self-rated health is characterized. The two studies that examine change at the high end of the distribution, the likelihood of reporting ‘excellent’ health, both found significant increases due to the DCE, one of 6.2% and the other of 1.5%. However, one of these studies found no effect when the outcome was expanded to include ‘very good’ health. Two studies which examined the opposite end of the spectrum, the likelihood of reporting ‘fair or poor’ health, have conflicting findings, despite using the same survey dataset (BRFSS); one reports a decrease of 0.8% in ‘fair or poor’ health and one reports no effect on reporting ‘fair or poor’ health. The study finding no effect used data from a shorter time period, which may account for the divergent results. One study found that the DCE increased the average self-rated health.

Table 6.

Studies of the Impact of the ACA DCE on Self-Rated Health Status

| Paper | Intervention | Control | Time Period | Data Source |

Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group |

Sample Size |

Age Group |

Sample Size |

Pre- DCE |

Post-DCE | |||

| (Wallace & Sommers, 2015) | 19-25 | 142,356 | 26-34 | 314,610 | 1/2005- 3/2010 |

9/2010- 12/2012 |

BRFSS | Decrease in ‘Fair or Poor’ SRH |

| (Carlson, Kail, Dreher, & Lynch, 2014) | 19-25 | 99,393 | 28-34 | 109,866 | 2006- 2007 |

2010- 2011 |

CPS | Increase in average SRH |

| (Chua & Sommers, 2014) | 19-25 | 26,453 | 26-34 | 34,052 | 2002- 2009 |

2011 | MEPS | Increase in ‘excellent’ SRH and ‘excellent’ SRMH |

| (Barbaresco et al., 2015) | 23-25 | 49,502 | 27-29 | 68,892 | 1/2007- 9/2010 |

10/2010- 12/2013 |

BRFSS | Increase in ‘excellent’ SRH. No effect on ‘very good or excellent’ SRH, days not in good mental or physical health, and days with health limitations |

| (Kotagal et al., 2014) | 19-25 | Not reported |

26-34 | Not reported |

2009 | 2012 | BRFSS | No effect on ‘fair or poor’ SRH |

BRFSS=Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CPS=Current Population Survey; MEPS=Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

The one paper to examine self-rated mental health found an increase of 4% in the likelihood of reporting excellent mental health (Chua & Sommers, 2014). A paper which examined the number of days spent with poor mental or physical health and days spent with health limitations found no effect of the DCE on these outcomes (Barbaresco et al., 2015).

Only one paper has examined impacts of the DCE on diet and health behaviors (Barbaresco et al., 2015). That paper, which analyzed data from the BRFSS (details on the sample shown in Table 6), found that the DCE increased risky drinking while reducing BMI and obesity. On the other hand, the study found no effects on the likelihood of being pregnant, smoking, or the total number of alcoholic drinks consumed per month.

Labor Market Participation

Two papers have examined the impact of the DCE on labor market participation, both using national survey data (Table 7). Both used DD models. One paper found a 5.8% reduction in the likelihood of working full-time, a 3% reduction in weekly work hours, and a 12% increase in the likelihood of having work hours that vary week to week. However, the same study found no effect of the DCE on being employed, changing jobs or changing employers (Akosa Antwi, Moriya, & Simon, 2013). The other paper to examine labor market outcomes found no evidence that the DCE affected the likelihood of switching employers (Bailey & Chorniy, 2015).

Table 7.

Studies of the Impact of the ACA DCE on Labor Market Outcomes

| Paper | Intervention | Control | Time Period | Data Source |

Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group |

Sample Size |

Age Group |

Sample Size |

Pre- DCE |

Post- DCE |

|||

| (Akosa Antwi et al., 2013) | 19-25 | 16,803 | 16-18 27-29 |

18,059 | 8/2008- 3/2010 |

9/2010- 11/2011 |

SIPP | Reduced probability of working full time and hours worked. Increased probability of having variable work hours. No effect on probability of being employed or changing jobs or employers. |

| (Bailey & Chorniy, 2015) | 19-25 | 46,992 | 16-18 27-32 |

57,894 | 5/2008- 8/2010 |

9/2010- 3/2013 |

CPS | No effect on changing employers |

SIPP= Survey of Income and Program Participation; CPS=Current Population Survey

DISCUSSION

The federal DCE is a market regulation that provides young adults with a convenient and inexpensive means of acquiring health insurance coverage. The policy has the potential for public health benefits because of the historically low level of insurance and low level of utilization of care among this age group. Insurance coverage can also protect young adults from the financial impact of high OOP expenditures on health care(Lau, Adams, Boscardin, & Irwin, 2014). However, the potential impact of the policy on public health involves a complex chain of events that link access to health insurance to changes in health care utilization, health behavior, and health status. The goal of this review is to assess the current state of evidence regarding this chain of events.

The evidence that the federal DCE had its desired direct effect on insurance coverage is strong. Studies of multiple datasets have found that the target age group gained insurance relative to an older age group during the time that the policy was implemented, and none have failed to find an effect. Moreover, the finding is specific to private health insurance—there is no evidence that the prevalence of public insurance increased or decreased among young adults during this time period relative to other age groups. This finding makes sense given that only those young adults whose parents or guardians have private health insurance have the opportunity to benefit from the DCE. Studies employing restricted samples to address potential methodological limitations of the most commonly used approach, discussed in more detail below, also found evidence of a positive effect of the federal DCE on insurance coverage.

Evidence of the impact of the DCE is weaker with subsequent indirect effects, both in terms of the number of studies that have examined downstream outcomes and the strength of the evidence for effects on these outcomes. Two papers, both based on analyses of the same survey, found a positive effect of the DCE on having a usual source of care, an important marker of access to care. Self-reports of cost as a barrier to care show mixed results. Similarly, evidence is mixed regarding the impact of the DCE on the OOP share of medical expenditures. Evidence is strongest for a reduction OOP costs at the high end of the range. Although this group may be small, the impact of the DCE may be quite large in preventing financially catastrophic medical costs among an age group with high levels of debt and low wages (Busch et al., 2014).

With respect to utilization of care, there is evidence for contrasting impacts of the DCE on ED visits and inpatient stays. With respect to ED visits, the evidence suggests that the number of visits was reduced while the likelihood of having one or more visits was not affected. This is the pattern we would find in the short-term if the insurance coverage enabled by the DCE had its desired effect of reducing frequent ED visits without reducing access to the ED when it is needed. With respect to inpatient stays, studies find an increase in the population rate (hospitalizations per person-year) but no effect on the prevalence of hospitalization (hospitalized persons as a proportion of the total population). However, this pattern of findings regarding inpatient stays may be an artifact of the types of studies examining these outcomes and not evidence of an effect of the DCE on recurrent hospitalization. The studies of the population rates of hospitalization have used administrative databases, which have more statistical power to detect effects than the surveys that have been used in studies of the prevalence of hospitalization.

The impact of the DCE on utilization of outpatient preventive and behavioral health care is particularly important for understanding the potential long term health impacts of the policy. Routine outpatient care can potentially improve health behaviors or management of chronic illnesses, either of which will have significant long term health burden across the adult lifespan. This is particularly true for behavioral health conditions, which are dramatically undertreated, particularly in this age group (R. C. Kessler et al., 2005). The preponderance of the current evidence suggests that the DCE has not had a broad impact on use of these services. A minority of studies finds evidence of increases in specific preventive procedures, such as blood pressure measurement, but the majority of studies find no effect on the majority of outcomes in this domain examined.

The one possible exception is the finding of a positive impact of the DCE on use of mental health treatment among people with mental health problems (Saloner & Le Cook, 2014), which is consistent with the increase in utilization of ED and hospital psychiatric services noted above. This finding is particularly interesting in light of the finding from The Oregon Experiment, a study of the effect of Medicaid enrollment that took advantage of randomized assignment through a lottery system. In that study, Medicaid enrollment did not have effects on physical health care, but it did have a positive effect on the likelihood of being diagnosed with depression (Baicker et al., 2013). To date, the evidence regarding the effect of the DCE on outpatient psychiatric treatment is limited to a single study, but the evidence supports the suggestion that increasing access to health care has a distinctive effect on mental health care.

An increase in utilization of outpatient psychiatric treatment among people with psychiatric disorders would be an important success of the policy. Onset of psychiatric disorders during adolescence and early adulthood is associated with longer delay of treatment (Wang et al., 2005). Longer delay of treatment, often referred to as ‘duration of untreated illness, is associated with poorer response to treatment and worse clinical prognosis (Ghio et al., 2015; Perkins, Gu, Boteva, & Lieberman, 2005). The impact of the DCE on mental health care could have important population level public health impacts by hastening treatment and reducing the life course impact of psychiatric disorders.

Studies of the impact of the DCE on health status should be interpreted in the light of these largely negative findings regarding utilization of the medical services most likely to directly affect health. The findings regarding self-rated health, which suggest improvements specific to the high end of the distribution in particular raise question regarding the mechanism through which they might have come about. Rather than a direct effect of treatment for clinical conditions, which would be more likely to have an impact at the opposite end of the score distribution, the effect observed might be due to a more general improvement in health security, i.e. a greater sense of being protected from potential health shocks.

To date there is only one study which has examined a broader range of health status indicators, and the results of that study suggest complex and possibly countervailing effects (Barbaresco et al., 2015). Specifically, the study found positive effects on weight and negative effects on heavy consumption of alcohol. The authors suggest that these two effects could both be downstream results of increases in insurance coverage. Specifically, they note that weight may be influenced by access to medical information and the ability to regularly monitor weight, while heavy alcohol consumption may be influenced by ‘ex ante moral hazard’, i.e. anticipation of access to medical care makes people more likely to engage in behavior that threatens their health, which has been reported by prior research on Medicaid expansion (Finkelstein et al., 2012). Given the short time frame over which the weight effect is believed to occur and the lack of a significant increase in utilization of outpatient medical care, this explanation of the impact of the DCE on weight seems speculative. Additional investigation could provide insight into the influence of insurance coverage on health behaviors that have tended to be resistant to many medical interventions. These interesting findings from a single study suggest a need for replication in other datasets, further tests of their robustness, and inclusion of a broader range of behavioral outcomes in future studies.

The small amount of research on labor market behavior conducted to date has provided evidence of some anticipated effects of the DCE, in particular an increase in the flexibility of work hours. This change has generally been interpreted as a positive effect; with insurance coverage through their families, young adults are less constrained in their labor market decision-making by the need to work full-time in order to qualify for employer based coverage.

Methodological Concerns

Nearly all of the reviewed studies use the same analytic approach; DCE effects are estimated from DD models applied to data on the target age group and a control age group taken from repeated cross-sectional samples. The strength of the DD model is its potential to mitigate bias due to contemporaneous secular trends, which are assumed to be similar in the intervention and control groups. The key model assumption is that the trends in each of the outcomes would have been the same in the intervention and control groups if the DCE had not been implemented. Given the near uniformity of the methods, the validity of this assumption is an important concern affecting all the research reviewed here. For example, recent historical events, such as the financial crisis of 2008 and the long economic recovery, may have caused different secular trends in the outcomes across different age groups. Age-related secular trends, such as trends in BMI (Ogden, Carroll, Fryar, & Flegal, 2015; Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012), or economic stressors that were more severe for adults entering the job market may have affected the age-based intervention and control groups differently. Severe violations to the model assumption of DD can bias the estimated effects of the DCE.

While the assumption that secular trends would have been similar in the intervention and control groups in the absence of the DCE cannot be directly tested, several studies attempted to empirically assess the plausibility of the assumption. Three studies used ‘placebo tests’, i.e. they tested whether significant DD model results would be found if the same groups were compared using time points at which no policy changes affecting coverage occurred. These studies found a relatively small number of statistically significant placebo effects, and that the magnitude of the effects was smaller for the placebo tests than for the test using the actual DCE implementation date (Akosa Antwi et al., 2013; Akosa Antwi et al., 2015; Barbaresco et al., 2015; Slusky, 2015). In addition, when the age bands were narrowed the number of significant placebo tests was reduced while the test using the actual DCE implementation data remained statistically significant (Barbaresco et al., 2015; Slusky, 2015). Some other studies have reported tests of parallel trends across the intervention and control age groups in years prior to the DCE. These studies report that the evidence supports parallelism, supporting the model assumption, but do not provide detailed information on how the test for parallelism were conducted (Wallace & Sommers, 2015). More nuanced issues regarding the scale on which parallelism is tested, e.g. probability, logit or probit, and methods for generating estimates of causal effects from non-linear models(Karaca-Mandic, Norton, & Dowd, 2012; Lechner, 2010) are not discussed in any of the papers we reviewed.

Though the methodological studies are encouraging, the evidence for the impact of the DCE, particularly with respect to the downstream outcomes of health and labor market behaviors, would be considerably strengthened by evidence using methods that do not depend on the same assumptions as the DD model used in the overwhelming majority of studies. To date, only one study uses an alternative design. That study examined whether change in insurance status accounted for change in preventive care utilization.

Conclusion

Evidence to date on the impact of the DCE suggests that it has had a positive public health impact, and, more generally, that increasing insurance coverage among young adults can positively influence some aspects of health care utilization, behavioral health care in particular, and health status. In this regard the evidence confirms prior studies which suggested that expanding coverage for young adults may enable them to develop an ongoing relationship with a health care provider (e.g., a primary care physician), and promote utilization in primary care settings over more expensive care settings (e.g., ED) (Baicker et al., 2013; Manning et al., 1987). However, the evidence also indicates that the impact of the DCE on utilization of preventive outpatient care other than behavioral health care is limited. This suggests that young adults may not be inclined to utilize available options for preventive care even if they have health insurance coverage. Additional efforts to encourage utilization of evidence based care during this age period may remain a priority even after the barrier of uninsurance is removed. Finally, thus far the evidence is sparse with respect to the impact of the DCE on the ultimate goals of improving the health status of young adults. Evidence showing positive effects on self-rated health is promising, but future research, perhaps covering a longer follow-period than has been possible in the past, will be required to determine whether the DCE has had long-term impacts on public health.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 MD010274).

REFERENCES

- Akosa Antwi Y, Moriya AS, Simon K. Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act's Dependent-Coverage Mandate. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2013;5(4):1–28. doi:doi: 10.1257/pol.5.4.1. [Google Scholar]

- Akosa Antwi Y, Moriya AS, Simon KI. Access to health insurance and the use of inpatient medical care: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act young adult mandate. Journal of Health Economics. 2015;39:171–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.11.007. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MM, Chen J, Mutter R, Novak P, Mortensen K. The ACA's Dependent Coverage Expansion and Out-of-Pocket Spending by Young Adults With Behavioral Health Conditions. Psychiatr Serv. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500346. appips201500346. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antwi YA, Moriya AS, Simon K, Sommers BD. Changes in Emergency Department Use Among Young Adults After the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's Dependent Coverage Provision. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(6):664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.01.010. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, Finkelstein AN. The Oregon Experiment — Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(18):1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. doi:doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J, Chorniy A. Employer-provided health insurance and job mobility: Did the affordable care act reduce job lock? Contemporary Economic Policy. 2015 doi:10.1111/coep.12119. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresco S, Courtemanche CJ, Qi YL. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision on health-related outcomes of young adults. Journal of Health Economics. 2015;40:54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SH, Golberstein E, Meara E. ACA dependent coverage provision reduced high out-of-pocket health care spending for young adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1361–1366. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0155. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantiello J, Fottler MD, Oetjen D, Zhang NJ. Determinants of health insurance coverage rates for young adults: An analytical literature review. Adv Health Care Manag. 2011;11:185–213. doi: 10.1108/s1474-8231(2011)0000011011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor JC, Belloff D, Monheit AC, DeLia D, Koller M. Expanding Dependent Coverage for Young Adults: Lessons from State Initiatives. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2012;37(1):99–128. doi: 10.1215/03616878-1496056. doi: http://jhppl.dukejournals.org/content/by/year. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor JC, Monheit AC, DeLia D, Lloyd K. Early Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage of Young Adults. Health Services Research. 2012;47(5):1773–1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01458.x. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DL, Kail B, Dreher M, Lynch JL. The Affordable Care Act, Dependent Health Insurance Coverage, and Young Adults' Health*. Sociological Inquiry. 2014;84(2):191–209. doi:10.1111/soin.12036. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Bustamante AV, Tom SE. Health care spending and utilization by race/ethnicity under the Affordable Care Act's dependent coverage expansion. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):S499–507. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302542. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua K, Sommers BD. Changes in health and medical spending among young adults under health reform. Jama. 2014;311(23):2437–2439. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2202. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Ward B, Schiller J. Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey. 20112010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201106.pdf.

- Collins SR, Garber T, Robertson R. Realizing health reform's potential: how the Affordable Care Act is helping young adults stay covered. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2011;5:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, Group, t. O. H. S. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year + The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2012 doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. doi:10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghio L, Gotelli S, Cervetti A, Respino M, Natta W, Marcenaro M, Belvederi Murri M. Duration of untreated depression influences clinical outcomes and disability. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;175:224–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.014. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Busch SH, Zaha R, Greenfield SF, Beardslee WR, Meara E. Effect of the Affordable Care Act's Young Adult Insurance Expansions on Hospital-Based Mental Health Care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172(2):182–189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030375. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Yabroff KR, Robbins AS, Zheng Z, Jamal A. Dependent coverage and use of preventive care under the affordable care act. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(24):2341–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1406586. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1406586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Boussard T, Burns CS, Wang NE, Baker LC, Goldstein BA. The Affordable Care Act Reduces Emergency Department Use By Young Adults: Evidence From Three States. Health Affairs. 2014;33(9):1648–1654. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0103. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhamb J, Dave D, Colman G. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Utilization of Health Care Services among Young Adults. International Journal of Health and Economic Development. 2015;1(1):8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca-Mandic P, Norton EC, Dowd B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1):255–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01314.x. Pt 1. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas K, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotagal M, Carle AC, Kessler LG, Flum DR. Limited impact on health and access to care for 19- to 25-year-olds following the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(11):1023–1029. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1208. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JS, Adams SH, Boscardin WJ, Irwin CE., Jr. Young adults' health care utilization and expenditures prior to the Affordable Care Act. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(6):663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.001. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JS, Adams SH, Park J, Boscardin WJ, Irwin CE. Improvement in Preventive Care of Young Adults After the Affordable Care Act The Affordable Care Act Is Helping. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(12):1101–1106. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1691. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner M. The estimation of causal effects by difference-in-difference methods. Foundations and Trends in Econometrics. 2010;4(3):165–224. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WG, Newhouse JP, Duan N, Keeler EB, Leibowitz A, Marquis MS. Health insurance and the demand for medical care: evidence from a randomized experiment. Am Econ Rev. 1987;77(3):251–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monheit AC, Cantor JC, DeLia D, Belloff D. How have state policies to expand dependent coverage affected the health insurance status of young adults? Health Serv Res. 2011;46(1):251–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01200.x. Pt 2. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara B, Brault MW. The Disparate Impact of the ACA-Dependent Expansion across Population Subgroups. Health Services Research. 2013;48(5):1581–1592. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12067. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(219):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. PRevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among us children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA. Relationship Between Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Outcome in First-Episode Schizophrenia: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785–1804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785. doi:doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, Le Cook B. An ACA provision increased treatment for young adults with possible mental illnesses relative to comparison group. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1425–1434. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0214. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JW, Salim A, Sommers BD, Tsai TC, Scott KW, Song ZR. Racial and Regional Disparities in the Effect of the Affordable Care Act's Dependent Coverage Provision on Young Adult Trauma Patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2015;221(2):495–U761. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.032. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JW, Sommers BD, Tsai TC, Scott KW, Schwartz AL, Song Z. Dependent Coverage Provision Led To Uneven Insurance Gains And Unchanged Mortality Rates In Young Adult Trauma Patients. Health Affairs. 2015;34(1):124–133. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0880. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane DM, Ayyagari P. Will health care reform reduce disparities in insurance coverage?: Evidence from the dependent coverage mandate. Med Care. 2014;52(6):528–534. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000134. doi:10.1097/mlr.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusky DJ. Significant Placebo Results in Difference-in-Differences Analysis: The Case of the ACA’s Parental Mandate. Eastern Economic Journal. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Sommers BD. Number of Young Adults Gaining Insurance Due to the Affordable Care Act Now Tops 3 Million. 2012 Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/number-young-adults-gaining-insurance-due-affordable-care-act-now-tops-3-million.

- Sommers BD, Buchmueller T, Decker SL, Carey C, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act Has Led To Significant Gains In Health Insurance And Access To Care For Young Adults. Health Affairs. 2013;32(1):165–174. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0552. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers BD, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage for young adults. Jama. 2012;307(9):913–914. doi: 10.1001/jama.307.9.913. doi:10.1001/jama.307.9.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J, Sommers BD. Effect of dependent coverage expansion of the Affordable Care Act on health and access to care for young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):495–497. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3574. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]