Abstract

Anthracnose disease caused by Colletotrichum species is a major constraint for the shelf-life and marketability of avocado fruits. To date, only C. gloeosporioides sensu lato and C. aenigma have been reported as pathogens affecting avocado in Israel. This study was conducted to identify and characterize Colletotrichum species associated with avocado anthracnose and to determine their survival on different host-structures in Israel. The pathogen survived and over-wintered mainly on fresh and dry leaves, as well as fresh twigs in the orchard. A collection of 538 Colletotrichum isolates used in this study was initially characterized based on morphology and banding patterns generated according to arbitrarily primed PCR to assess the genetic diversity of the fungal populations. Thereafter, based on multi-locus phylogenetic analyses involving combinations of ITS, act, ApMat, cal, chs1, gapdh, gs, his3, tub2 gene/markers; eight previously described species (C. aenigma, C. alienum, C. fructicola, C. gloeosporioides sensu stricto, C. karstii, C. nupharicola, C. siamense, C. theobromicola) and a novel species (C. perseae) were identified, as avocado anthracnose pathogens in Israel; and reconfirmed after pathogenicity assays. Colletotrichum perseae sp. nov. and teleomorph of C. aenigma are described along with comprehensive morphological descriptions and illustrations, for the first time in this study.

Introduction

Avocado (Persea americana Mill.) is a high value crop grown in tropical and subtropical areas worldwide, including the Mediterranean basin. Israel is one of the prominent exporters of avocadoes in the world1, cultivated in approximately 7,000 hectares mainly along the Northern coastal plain to the Gaza strip in the South, and Eastern Galilee and Jordan Valley regions, yielding ca. 100,000 tons of fruit annually. Approximately 70% of the total production is exported to European countries while ca. 30% is utilized for local consumption2. Under subtropical Mediterranean conditions such as those prevailing in Israel, avocado fruit that set during the winter are seriously affected by post-harvest anthracnose fruit decay caused by Colletotrichum species3. Therefore, shelf life and marketability of avocado fruits are significantly reduced4. Colletotrichum is amongst the top ten fungal pathogens5; causing anthracnose disease in many economically important crops worldwide6–12. Anthracnose is characterized by the appearance of sunken necrotic black lesions along with the formation of orange conidial mass13,14. Infections of avocado occur in the orchard whereby conidia of the pathogen germinate, form appressoria but remain quiescent until fruit ripening after harvest15. Epidemiology of avocado anthracnose has not been studied in Israel and thus the source of inoculum affecting fruit has yet to be determined. It is plausible to assume that the source of conidia quiescently affecting fruit during the wet winters may originate from leaves or branches (dry or fresh) that are dispersed to the fruitlets and fruits formed during this period16. In tropical regions, it has been reported that the fungus survives between fruiting cycles on dried avocado leaves and twigs, either in the plant canopy or on the ground17.

Due to the worldwide importance of Colletotrichum as a plant pathogenic genus, accurate diagnosis is essential to improve bio-security and disease management strategies6–8,18. In particular, species belonging to the C. gloeosporioides species complex are pervasive, and are known to be common pathogens in tropical and subtropical areas19–35. Host-association and morphological characterization was previously used to identify Colletotrichum species6,7; but due to the overlapping morphological characters, a polyphasic approach is now recommended for accurate species identification within this genus18,36,37. Following the major taxonomic re-assessments in Colletotrichum 9–12,38–41, it is crucial to update the existing host-pathogen records. The recommended genes to be used in the phylogenetic analysis of the major Colletotrichum species complexes are respectively: Acutatum/Destructivum/Orbiculare/Spaethianum/Truncatum species complexes – act (actin), chs1 (chitin synthase), gapdh (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), his3 (histone), ITS (5.8 S ribosomal RNA and the flanking internal transcribed spacer regions), tub2 (β-tubulin); Boninense species complex – act, cal (calmodulin), chs1, gapdh, his3, ITS, tub2; Dematium/Gigasporum/Graminicola species complexes – act, chs1, gapdh, ITS, tub2; and the Gloeosporioides species complex - act, cal, chs1, gapdh, ITS9–12,38–41. Within the C. gloeosporioides species complex, use of the intergenic region between apn2 and Mat1-2 genes (ApMat) has been shown to be effective in cryptic species delimitation21,24,27,42.

To date, only two Colletotrichum species: C. gloeosporioides sensu lato and C. aenigma have been reported to be associated with avocado in Israel11,43. Due to the serious damage to avocado fruit caused by anthracnose disease in Israel, this study was initiated to (i) determine the genetic diversity of Colletotrichum using arbitrarily primed PCR (ap-PCR), multi-locus DNA sequence data coupled with morphology and pathogenicity assays; and (ii) determine on which plant organs the pathogen survives and over-winters under field conditions, in order to understand epidemiology of disease to help contribute to management practices.

Results

Fungal isolates and host infections

A total of 576 Colletotrichum isolates were recovered from different tissue (fruits, fresh leaves, fresh twigs, dry leaves and dry twigs) of avocado (Supplementary Table 1). Percentage of Colletotrichum isolates obtained from different host tissues is presented in Fig. 1. The Colletotrichum isolates were most readily isolated from infected fruits (94.88%), as compared to green leaves (19.87%), green twigs (10.93%) and dry leaves (18%) showing typical anthracnose symptoms. Low infection values of 0.9% were recorded for dry and dead twig tissues. Morphologically identical isolates recovered from the same tissue samples during isolation were discarded and 538 isolates were then selected for further molecular characterization.

Figure 1.

Bar diagram representing the percentage of Colletotrichum isolates obtained from different avocado host tissues. Bars represent the standard errors of mean for each tissue sample.

Assessment of genetic diversity

Amplification products were obtained for all the 538 Colletotrichum isolates from this study using four arbitrarily primed PCR (ap-PCR) primers: (CAG)5, (GACA)4, (AGG)5 and (GACAC)3. A high level of genetic diversity was observed, categorizing the isolates into eight distinct genetic groups (Supplementary Text). Genetic variability between the representative isolates from each group is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Thirty-three isolates were then selected from the eight genetically distinct groups based on their geographical location and isolation-tissue, for further multi-gene phylogenetic analyses, pathogenicity testing and morphological characterization.

Identification of species complex using ITS gene region

Following assessment of genetic diversity, the ITS gene region of the 33 isolates was sequenced for their preliminary identification to the species complex level. Based on NCBI-BLAST search results of the ITS sequences, 31 isolates belonged to the C. gloeosporioides species complex and two isolates belonged to the C. boninense species complex. Further phylogenetic analyses were performed according to the described set of gene markers for the respective species complexes9,11. NCBI accession numbers for the sequences generated in this study appear in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

GenBank accession numbers of the Colletotrichum isolates belonging to the C. gloeosporioides species complex sequenced for the ITS, gapdh, act, tub2, cal, ApMat and gs gene sequences from this study (N.S. = not sequenced, T = type strain of the newly described species, in bold).

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers of the Colletotrichum isolates belonging to the C. boninense species complex sequenced for the ITS, act, chs1, his3, tub2, cal and gapdh gene sequences from this study.

ApMat marker based phylogenetic analysis of the C. gloeosporioides species complex members

The ApMat dataset included 58 sequences and 944 characters including gaps. Forty-one characters from the ambiguously-aligned regions were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 903 characters, 398 characters were constant, 320 characters were parsimony-informative and 185 characters were parsimony-uninformative. MP analysis resulted in two trees and based on the KH test, the second tree was not significantly different as compared to the best tree (details not shown). One tree (TL = 832, CI = 0.773, RI = 0.932, RC = 0.721, HI = 0.227) generated in the MP analysis is shown in Fig. 2. The tree is rooted with C. xanthorrhoeae ICMP 17903. The recently described Colletotrichum species: C. chengpingense, C. conoides, C. endophytica, C. grevilleae, C. grossum, C. hebeinse, C. helleniense, C. hystricis, C. liaoningense, C. proteae and C. syzygicola; were not included in the analysis due to unavailability of ApMat sequences from the reference type strains. Bootstrap support values exceeding 50% for the observed branching pattern are shown next to the branch nodes. ApMat analysis resulted in strongly supported terminal clades (most branches having bootstrap support >70%). Using ApMat marker based phylogeny, 31 isolates belonging to the C. gloeosporioides species complex from this study were identified as C. aenigma, C. alienum, C. fructicola, C. gloeosporioides sensu stricto, C. nupharicola, C. siamense, C. theobromicola and one novel lineage described in this paper as C. perseae sp. nov.

Figure 2.

One of the two most parsimonious trees showing phylogenetic affinities of Colletotrichum isolates (highlighted in blue) belonging to the C. gloeosporioides species complex from Israel, obtained from heuristic search of the ApMat dataset. Colletotrichum xanthorrhoeae ICMP 17903 is used as an outgroup, and bootstrap support values exceeding 50%, are indicated at the nodes. (Type strains are marked with T).

Colletotrichum spp. isolates GA002 and GA006 clustered with the ex-type isolate of C. theobromicola (ICMP 18649) with 100% bootstrap support. Colletotrichum spp. isolates GA070, GA077, GA078 and GA125 clustered with the ex-type isolate of C. gloeosporioides sensu stricto (ICMP 17821) with 100% bootstrap support. Colletotrichum spp. isolates GA131, GA228, GA250, GA252, GA263, GA331 and GA435 clustered with the ex-type isolate of C. siamense (ICMP 18578) with 99% bootstrap support. Colletotrichum sp. isolate GA524 clustered with the ex-type isolate of C. alienum (ICMP 12071) with 90% bootstrap support. Colletotrichum sp. isolate GA186 clustered with the ex-type isolate of C. fructicola (ICMP 18581) with 88% bootstrap support. Colletotrichum sp. isolate GA253 clustered with the ex-type isolate of C. nupharicola (CBS 470) with 92% bootstrap support. Colletotrichum spp. isolates GA098, GA230 and GA512 clustered with the ex-type isolate of C. aenigma (ICMP 18608) with 81% bootstrap support. Colletotrichum spp. isolates GA039, GA100, GA177, GA272, GA319, GA320, GA335, GA341 and GA424 formed a distinct clade with 100% bootstrap support, adjacent to C. fructicola, C. nupharicola and C. alienum, described in this paper as C. perseae sp. nov.

Multigene phylogenetic analyses of the C. gloeosporioides species complex members

Three Colletotrichum species viz. C. fructivorum, C. rhexiae and C. temperatum were excluded from the multi-gene analysis due to unavailability of reference sequences [act, cal, gapdh, glutamine synthase (gs)]. In addition, reference sequences were also lacking for C. endophytica (tub2); C. chengpingense, C. hebeinse (cal); and C. chengpingense, C. conoides, C. endophytica, C. grossum, C. hebeinse, C. helleniense, C. hystricis, C. liaoningense (gs). The 6-gene (act, cal, gapdh, gs, ITS, tub2) and 5-gene (act, cal, gapdh, ITS, tub2) phylogenetic analyses involved 69 taxa, including 31 isolates from this study and 38 reference isolates of the C. gloeosporioides species complex. C. xanthorrhoeae (ICMP 17903) was the designated outgroup. A further analysis including combined datasets of the ApMat marker and gs gene regions was also performed; to compare and validate the results of ApMat based phylogeny with the multigene phylogeny.

The 6-gene dataset (act, cal, gapdh, gs, ITS, tub2) included 3628 characters with alignment gaps. Two hundred and twelve characters from the ambiguously aligned regions were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 3416 characters processed, 549 characters were parsimony-informative, 713 parsimony-uninformative and 2154 constant. Gene boundaries in the 6-gene dataset included; ITS: 1–590, act: 591–866, cal: 867–1651, gapdh: 1652–1955, gs: 1956–2878, tub2: 2879–3628). A heuristic search using PAUP resulted in 240 trees, of which one is shown in Fig. 3 (length = 2107, CI = 0.728, RI = 0.844, RC = 0.614, HI = 0.272). The topologies of the 240 trees were not significantly different (details not shown). The clustering pattern for the 31 isolates from 6-gene analysis was comparable to ApMat-based phylogeny and the overall bootstrap support for individual branches was typically strong [C. aenigma (88%), C. fructicola (100%), C. gloeosporioides (100%), C. nupharicola (69%), C. perseae sp. nov. (100%), C. siamense (78%), C. theobromicola (100%)]. The 5-gene (act, cal, gapdh, ITS, tub2) phylogenetic analysis (data not shown) was incapable of resolving C. siamense, C. gloeosporioides, C. theobromicola, C. alienum, C. fructicola and C. nupharicola into strongly supported clades. However, C. aenigma and C. perseae sp. nov. were resolved with 88% and 100% bootstrap support values, respectively.

Figure 3.

One of the 264 most parsimonious trees showing phylogenetic affinities of Colletotrichum isolates (highlighted in blue) belonging to the C. gloeosporioides species complex from Israel, obtained from heuristic search of the 6-gene (act, cal, ITS, gapdh, gs, tub2) dataset. Colletotrichum xanthorrhoeae ICMP 17903 is used as an outgroup, and bootstrap support values exceeding 50%, are indicated at the nodes. (Type strains are marked with T).

The ApMat-gs dataset included 1867 characters including gaps (gene boundaries ApMat: 1–944, gs: 945–1867). The analysis involved 55 sequences, including 31 sequences from this study. Ninety-one characters from the ambiguously aligned regions were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 1776 characters, 965 were constant, 463 were parsimony-informative and 348 were parsimony-uninformative. The MP analysis resulted in one tree (TL = 1290, CI = 0.763, RI = 0.905, RC = 0.690, HI = 0.237) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The bootstrap support values exceeding 50% for the observed branching pattern are indicated next to the branches. The ApMat-gs tree is strongly supported with high bootstrap values as compared to the 6-gene phylogeny [C. aenigma (100%), C. alienum (98%), C. fructicola (100%), C. gloeosporioides (100%), C. nupharicola (66%), C. perseae sp. nov. (100%), C. siamense (93%), C. theobromicola (100%)]. The topology of the ApMat-gs tree is in congruence with ApMat-phylogeny and the 6-gene phylogeny.

7-gene based phylogenetic analysis of the C. boninense species complex (act, cal, chs1, gapdh, his3, ITS, tub2)

The multi-gene analysis dataset included 2772 characters with alignment gaps (gene boundaries were, chs1: 1–280, ITS: 281–840, act: 841–1119, cal: 1120–1572, gapdh: 1573–1874, his3: 1875–2269, tub2: 2270–2772). The analysis involved 25 taxa, including 2 isolates from this study, 22 reference isolates belonging to the C. boninense species complex and the outgroup (C. gloeosporioides strain CBS 112999). Eighty-four characters from the ambiguously aligned regions were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 2688 characters, 1892 were constant, 396 were parsimony-informative and 400 were parsimony-uninformative. The MP analysis resulted in one tree (TL = 1341, CI = 0.759, RI = 0.800, RC = 0.607, HI = 0.241), as shown in Fig. 4. The two isolates from this study, GA206 and GA423, clustered within the C. karstii clade with 100% bootstrap support.

Figure 4.

One of the most parsimonious trees showing phylogenetic affinities of Colletotrichum isolates (highlighted in blue) belonging to the C. boninense species complex from Israel, obtained from heuristic search of the 7-gene (act, cal, chs1, ITS, gapdh, his3, tub2) dataset. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides CBS 112999 is used as an outgroup, and bootstrap support values exceeding 50%, are indicated at the nodes. (Type strains are marked with T).

Pathogenicity assay

The inoculated fruits developed typical anthracnose lesions around the wound (Fig. 5); however, disease development at the unwounded site was very limited or absent even after seven days post inoculation (data not shown). To validate Koch’s postulates, pathogens were re-isolated from the infected host tissues. The control fruits did not develop anthracnose symptoms. All Colletotrichum isolates from this study caused 100% disease incidence. Colletotrichum aenigma proved to be the most virulent pathogen of avocado in Israel with 92.6 ± 7.7% disease severity (Table 3). The next two virulent pathogens were C. alienum and C. theobromicola with 90.1 ± 6.7 and 88.9 ± 3.7% disease severity scores, respectively. The percent disease severity (PDS) scores for other isolates were: C. siamense (85.9 ± 4.3%), C. fructicola (85.2 ± 4.3%), C. gloeosporioides (82.7 ± 5.0%), C. perseae sp. nov. (80.2 ± 2.7%), C. karstii (67.9 ± 6.5%) and C. nupharicola (63.0 ± 14.7%). Pathogenicity assays were performed in triplicate, and similar results were obtained for each experiment (data not shown). Calculations for the results of PDS are provided in Table 3.

Figure 5.

Results of pathogenicity assays of selected Colletotrichum species isolates (C. aenigma – GA050, C. alienum – GA524, C. fructicola – GA186, C. gloeosporioides – GA070, C. karstii – GA206, C. nupharicola – GA253, C. perseae sp. nov. – GA100, C. siamense – GA331, C. theobromicola – GA002) 7 days post inoculation on (a) Reed and (b) Hass avocado cultivars. Control fruit was mock-inoculated with sterile water.

Table 3.

Disease score (DS), percent disease incidence (PDI) and percent disease severity (PDS) for each fruit (cultivar), 7 days post inoculation with representative strains of Colletotrichum species.

| Isolate | Disease Score (DS) on a 0–9 scale | PDI (%) | Mean PDS (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control fruit | Replicate 1 (Reed) | Replicate 2 (Reed) | Replicate 3 (Hass) | ||||||||||||

| Test fruit 1 | Test fruit 2 | Test fruit 3 | PDS (%) | Test fruit 4 | Test fruit 5 | Test fruit 6 | PDS (%) | Test fruit 7 | Test fruit 8 | Test fruit 9 | PDS (%) | ||||

| GA050 (C. aenigma) | 0 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 100% | 9 | 9 | 9 | 100% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 100% | 92.59 ± 7.66 |

| GA524 (C. alienum) | 0 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 92.59% | 9 | 9 | 9 | 100% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 100% | 90.12 ± 6.74 |

| GA186 (C. fructicola) | 0 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 92.59% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 9 | 7 | 7 | 85.18% | 100% | 85.18 ± 4.33 |

| GA070 (C. gloeosporoides) | 0 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 92.59% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 100% | 82.71 ± 5.00 |

| GA206 (C. karstii) | 0 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 7 | 5 | 7 | 70.37% | 7 | 1 | 7 | 55.55% | 100% | 67.89 ± 6.48 |

| GA253 (C. nupharicola) | 0 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 5 | 1 | 3 | 33.33% | 100% | 62.95 ± 14.66 |

| GA100 = CBS 141365 (C. perseae sp. nov.) | 0 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 9 | 7 | 7 | 85.18% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 100% | 80.24 ± 2.66 |

| GA331 (C. siamense) | 0 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 92.59% | 7 | 7 | 7 | 77.77% | 7 | 7 | 9 | 85.18% | 100% | 85.88 ± 4.33 |

| GA002 (C. theobromicola) | 0 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 92.59% | 9 | 7 | 9 | 92.59% | 7 | 8 | 7 | 81.48% | 100% | 88.88 ± 3.66 |

PDI (%) = x/N × 100.

PDS (%) = Σ(a + b)/N.Z × 100.

Σ(a + b) = Sum of infected fruits and their corresponding score scale.

N = Total number of sampled fruits = 3.

Z = Highest score scale = 9.

x = Number of infected fruits = 3.

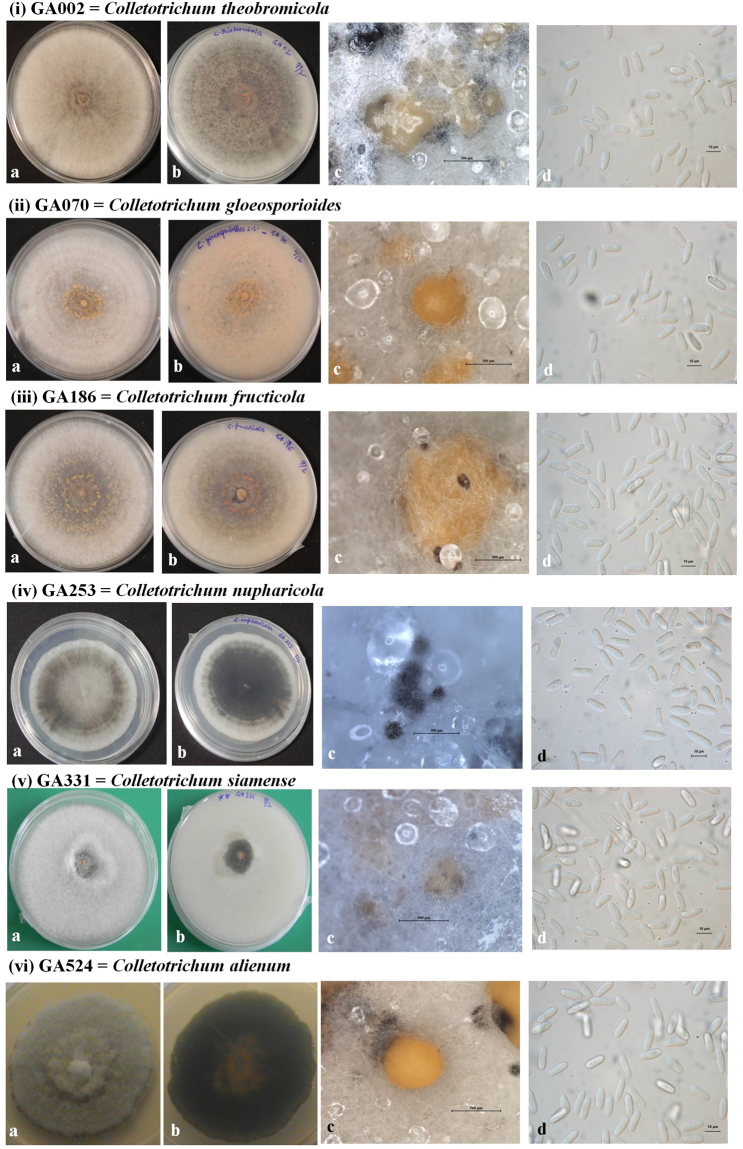

Morphological analysis

Morphological characters (colony morphology on PDA, conidial shape and size) along with growth rates for the reference Colletotrichum species isolates (C. aenigma – GA050, C. alienum – GA524, C. fructicola – GA186, C. gloeosporioides – GA070, C. karstii – GA206, C. nupharicola – GA253, C. perseae sp. nov. – GA100, C. siamense – GA331, C. theobromicola – GA002) were recorded and compared to that of their respective ex-type strains (Figs 6–9, Table 4). In general, shape, size of conidia and colony growth rates were comparable to the reference strains; with minor exceptions as follows. The colony growth rate of representative isolates of C. alienum was slower, whereas that of C. aenigma, C. karstii and C. nupharicola was faster, compared to that of their respective ex-type strains. Comparisons for length and width of conidia among the different isolates were conducted according to box plots, as shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 6.

Morphological features of selected isolates of Colletotrichum species (i) C. theobromicola – GA002, (ii) C. gloeosporioides – GA070, (iii) C. fructicola – GA186, (iv) C. nupharicola – GA253, (v) C. siamense – GA331 (vi) C. alienum – GA524. (a) Colony morphology on PDA (front) (b) Colony morphology on PDA (reverse) (c) Conidiomata/ascomata (d) Conidia (Scale bar of c = 500 μm, Scale bar of d = 10 μm).

Figure 9.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum karstii – GA206 (a) Colony morphology on PDA (front) (b) Colony morphology on PDA (reverse) (c) Conidiomata (d) Conidia (Scale bar of c = 500 μm, Scale bar of d = 10 μm).

Table 4.

Comparison of morphological characters of selected Colletotrichum isolates discussed in this study with the reference type strains (*, in bold).

| Taxon | Strain | Colony morphology | Conidia Length | Conidia Width | Conidia shape | Growth rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. alienum | GA524 | cottony, grey aerial mycelium; reverse dark grey to pale orange in centre | 14.5–20.0 μm Mean = 15.7 ± 0.2 μm | 3.5–6.5 μm Mean = 5.0 ± 0.1 μm | cylindrical with broadly rounded ends | 4.5 mm/day |

| C. alienum | ICMP 12071* | cottony, grey aerial mycelium; reverse dark grey to pale orange | 12.5–22.0 µm Mean = 16.5 ± 1.0 µm | 3.0–6.0 µm Mean = 5.0 ± 0.50 µm | cylindrical with broadly rounded ends | 8.5 mm/day |

| C. aenigma | GA050 | aerial mycelium sparse, white to grey; reverse dark grey | 14.0–22.0 μm Mean = 17.4 ± 0.2 μm | 4.5–7.0 μm Mean = 5.9 ± 0.1 μm | cylindrical with broadly rounded ends | 9.4 mm/day |

| C. aenigma | ICMP 18608* | aerial mycelium sparse, cottony, white; reverse pale orange | 12.0–16.5 µm Mean = 14.5 ± 0.5 µm | 5.0–7.5 µm Mean = 6.1 ± 0.2 µm | cylindrical with broadly rounded ends | 3.5 mm/day |

| C. fructicola | GA186 | cottony, pale orange aerial mycelium; reverse pale orange | 11.0–17.0 μm Mean = 14.1 ± 0.2 μm | 3.5–7.0 μm Mean = 5.0 ± 0.1 μm | cylindrical with slightly tapered ends | 11.6 mm/day |

| C. fructicola | ICMP 18581* | cottony, dense pale grey aerial mycelium | 9.7–14.0 µm Mean = 11.4 ± 0.9 µm | 3.0–4.5 µm Mean = 3.5 ± 0.35 µm | cylindrical | 10.7 mm/day |

| C. gloeosporioides | GA070 | cottony, pale orange aerial mycelium; reverse dark orange | 12.0–17.0 μm Mean = 14.2 ± 0.2 μm | 3.5–6.5 μm Mean = 5.2 ± 0.1 μm | cylindrical, obtuse at the apex | 10.5 mm/day |

| C. gloeosporioides | ICMP 17821* | grey to brown, with pinkish patches; reverse dark brown | 8.5–17.0 μm | 3.5–4.5 μm | straight, cylindrical, obtuse at the apex | 9.5 mm/day |

| C. karstii | GA206 | yellowish to orange with whitish margins; reverse pale grey to orange | 10.0–15.0 μm Mean = 13.5 ± 0.2 μm | 4.0–7.0 μm Mean = 5.7 ± 0.1 μm | straight, cylindrical, rounded at both ends | 8.9 mm/day |

| C. karstii | CBS 127597* | grey to white aerial mycelium; reverse colorless to pale orange | 14.5–17.0 μm | 5.0–6.5 μm | straight, cylindrical, rounded at both ends | 3.8 mm/day |

| C. nupharicola | GA253 | grey to white velvety mycelium; reverse dark grey to white | 12.5–17.5 μm Mean = 15.1 ± 0.2 μm | 4.5–7.0 μm Mean = 5.7 ± 0.1 μm | fusiform to cylindrical | 8.0 mm/day |

| C. nupharicola | ICMP 17939* | yellowish to orange with whitish margins | 14.0–53.0 μm | 5.0–10.0 μm | cylindrical to clavate | 4.3 mm/day |

| C. perseae sp. nov. | GA100* = CBS 141365* | cottony, white mycelium; reverse pale white to grey | 13.0–19.0 μm Mean = 15.7 ± 0.1 μm | 4.0–6.5 μm Mean = 5.2 ± 0.1 μm | straight, cylindrical, rounded or tapered ends | 10.4 mm/day |

| C. theobromicola | GA002 | cottony, pale orange to grey mycelium; reverse dark grey to orange | 11.0–15.0 μm Mean = 12.7 ± 0.2 μm | 4.5–7.0 μm Mean = 5.7 ± 0.1 μm | cylindrical, obtuse at the apex | 11.1 mm/day |

| C. theobromicola | ICMP 18649* | greyish mycelium | 14.5–18.7 μm | 4.5–5.5 μm | subcylindrical | 12.5 mm/day |

| C. siamense | GA331 | cottony, white to grey mycelium | 11.5–16.5 μm Mean = 13.6 ± 0.2 μm | 3.5–6.0 μm Mean = 4.6 ± 0.1 μm | fusiform to cylindrical | 11.4 mm/day |

| C. siamense | ICMP 18578* | Cottony, pale yellowish to pinkish mycelium | 7.0–18.3 µm | 3.0–6.0 µm | fusiform to cylindrical | 9.1 mm/day |

Figure 10.

Box plots showing the variation in length and width of conidia produced by the representative isolates examined in this study.

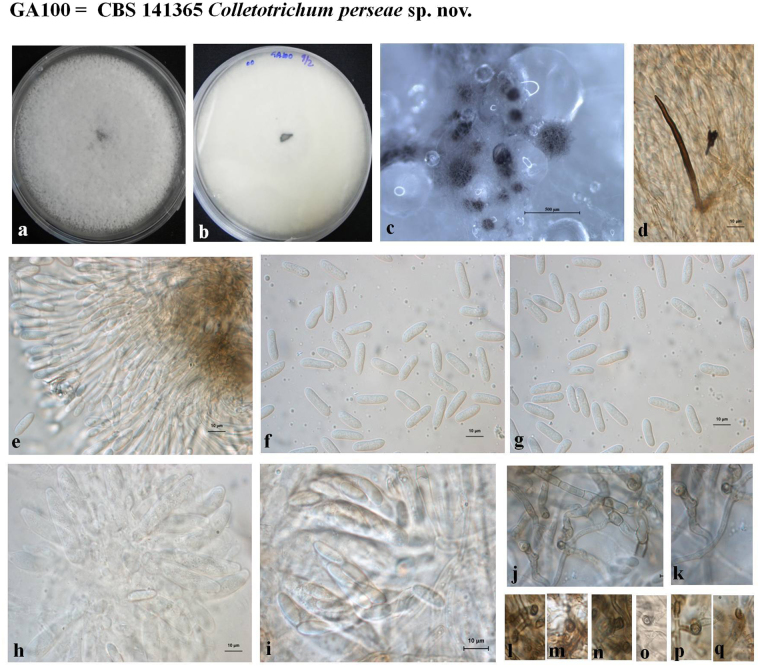

Taxonomy of novel Colletotrichum species

Colletotrichum perseae sp. nov G. Sharma & S. Freeman, sp. nov. MycoBank MB819960 Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum perseae sp. nov. – GA100 = CBS 141365 (a) Colony morphology on PDA (front) (b) Colony morphology on PDA (reverse) (c) Ascomata (d) Setae (e) Conidiogenous cells (f–g) Conidia (h–i) Asci and ascospores (j–q) Appressoria (Scale bar of c = 500 μm, Scale bar of d-q = 10 μm).

Etymology: The species epithet is derived from the host genus name Persea americana Mill.

Holotype: Israel, Mikve Israel, (central Israel), on Persea americana cv. Hass (avocado) ripe fruit rot (post-harvest), coll. S. Freeman GA100 1-12-2014, HUJIHERB-902850-FUNGI; ex-holotype culture CBS 141365.

Asexual morph on PDA. Colonies grown on PDA 105 mm diam. after 10 days, cottony, dense white aerial mycelium, with regular margin, no masses of conidial ooze, with scattered dark acervuli. In reverse, pale white with black coloration towards the center. Vegetative hyphae 1.5–7.5 µm diam., hyaline, smooth-walled, septate, branched. Conidiomata conidiophore and setae formed directly on hyphae. Setae approximately 50–90 µm long. Conidiogenous cells cylindrical, mostly 15–30 × 3.5–4 µm, arranged in closely packed palisade, conidiophores towards margins are irregularly branched, conidiogenous loci at apex. Conidia hyaline, straight, cylindrical, broadly rounded ends, usually tapering towards basal end, 13.0–19.0 × 4.0–6.5 µm (mean 15.7 × 5.2, n = 50). Appressoria irregularly shaped, dark brown, narrow.

Sexual morph on M3S. Perithecia occurring after 3–4 weeks in culture, oval or globose, scattered across plate, dark walled. Asci 40–65 × 8–10 µm, clavate with truncated apex, 8-spored. Ascospores hyaline, aseptate, slightly curved, tapering to rounded ends, 12.0–15.5 × 3.0–4.5 µm (mean 13.5 × 3.5, n = 30).

Geographic distribution: Known only from avocado (Persea americana Mill.) from Israel.

Genetic identification: ITS sequences are not sufficient to distinguish C. perseae from the species in the Fructicola clade. Colletotrichum perseae was well resolved using ApMat and gs markers.

Other specimens examined: Israel, Bet Dagan (central Israel), on Persea americana Mill. cv. Ettinger leaf spots, coll. S. Freeman GA039 12-11-2014; Mikve Israel (central Israel), on Persea americana cv. Hass dry leaf, coll. S. Freeman GA177 1-12-2014; Kfar Yuval (northern Israel), on Persea americana Mill. cv. Reed ripe fruit rot, coll. S. Freeman GA272 ( = CBS 141366) 1-4-2015; Beit Haemek (northern Israel), on Persea americana Mill. cv. Reed ripe fruit rot, coll. S. Freeman GA319, GA320, GA335, GA341 1-4-2015; Kfar Aza (southern Israel), on Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass stem rot, coll. S. Freeman GA424 1-4-2015.

Colletotrichum aenigma B. Weir & P.R. Johnst., MycoBank MB563759. Fig. 8.

Figure 8.

Morphological features of Colletotrichum aenigma – GA050 (a) Colony morphology on PDA (front) (b) Colony morphology on PDA (reverse) (c) Ascomata (d) Conidiogenous cells (e) Conidia (f–h) Asci and ascospores (Scale bar of c, f = 500 μm, Scale bar of d, e, g–h = 10 μm).

Etymology: From the Latin aenigma, based on the enigmatic biological and geographical distribution of this species.

Holotype: Israel, on Persea americana Mill., coll. S. Freeman Avo-37-4B, PDD 102233; ex-holotype culture ICMP18608.

Asexual morph on PDA: Detailed description provided in Weir et al. (2012).

Sexual morph on M3S: Perithecia occurring after 3–4 weeks in culture, scattered across plate, dark walled, globose. Asci 40–55 × 7–10 µm (n = 10), 8-spored. Ascospores slightly curved, rounded ends, 10.0–16.5 × 3.5–5.0 µm (mean 13.0 × 4.3, n = 30).

Geographic distribution: Israel (Persea americana Mill.) and Japan (Pyrus pyrifolia).

Genetic identification: ITS sequences are not sufficient to distinguish C. aenigma from C. alienum and the species in the Siamense clade. Colletotrichum aenigma is well resolved using ApMat, gs and tub2 markers.

Specimens examined: Israel, ARO orchard, Bet Dagan (central Israel), on Persea americana Mill. cv. Ettinger fruit rot, coll. S. Freeman GA050, 12-11-2014; ARO orchard, Bet Dagan, on Persea americana cv. Ettinger green leaf spots, coll. S. Freeman GA098, 12-11-2014; Kfar Aza (southern Israel), on Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass fruit rot, coll. S. Freeman GA221–224, GA226–227, GA230–246, GA248–249, GA251, GA255, GA258, GA261–262, GA264–267, 01-04-2015.

Discussion

Phenotypic plasticity within Colletotrichum species complexes is a key limiting factor in species delimitation. Although a polyphasic approach towards characterization of Colletotrichum species is a recommended strategy18; there is a lack of consensus among mycologists regarding the choice of markers to be used for multi-locus phylogeny37,44. Thus far, 11 species complexes of Colletotrichum have been distinguished: C. acutatum, C. boninense, C. caudatum, C. dematium, C. destructivum, C. gigasporum, C. gloeosporioides, C. graminicola, C. orbiculare, C. spaethianum, and C. truncatum 8–12,31,39–41,45. Besides these 11 species complexes, 23 single species and some independently evolved small clusters have been described e.g. C. dracaenophilum, C. yunnanense, C. cliviae and C. araceaerum 8,31,46. Each species complex is recognized by the specific epithet of a historically known or well-studied species37. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides sensu lato remains the most confusing taxa within the Colletotrichum genus. Following extensive taxonomic revisions8–12,39,40, attempts were made to investigate a potential secondary barcode for Colletotrichum. To date, ApMat and gs are reported to be efficient in species delimitation within the C. gloeosporioides species complex21,22,24,26,27,42. It is crucial to accurately identify a pathogen, for effective plant quarantine purposes, breeding programs and disease control47,48. This is especially important for economically important agricultural commodities such as avocado.

This study highlights the genetic heterogeneity of Colletotrichum populations associated with avocado anthracnose in Israel. Nine dominant Colletotrichum spp. causing avocado anthracnose were identified, including one new species, C. perseae sp. nov., based on multigene phylogeny, pathogenicity assays and morphology. Among the nine species identified in this paper; C. aenigma, C. alienum, C. fructicola, C. gloeosporioides, C. karstii and C. siamense have been previously reported from Persea americana 11,26,43,49. To date, only C. gloeosporioides sensu lato and C. aenigma have been reported from avocado in Israel3,11,14,43,50. This is the first report demonstrating pathogenicity of C. persea sp. nov., C. nupharicola and C. theobromicola, specifically in avocado. However, other Colletotrichum species affecting avocado in this study in Israel have been reported to attack diverse hosts. For example: Colletotrichum aenigma has been previously reported from Pyrus communis, Citrus sinensis (Italy) and Pyrus pyrifolia (Japan); C. alienum from Malus domestica (New Zealand); C. fructicola from Malus domestica (Brasil, USA), Fragaria sp. (Canada, USA), Limonium sp. (Israel), Pyrus pyrifolia (Japan), Dioscorea alata (Nigeria), Theobroma cacao (Panama), Coffea arabica (Thailand), Mangifera indica, Capsicum sp. (India); C. gloeosporioides from Citrus sp. (Italy, New Zealand, USA), Mangifera indica (South Africa, India), Carya illinoinensis (Australia), Ficus sp. (New Zealand), Vitis vinifera, Pueraria lobata (USA); C. karstii from Annona sp. (New Zealand, Mexico), Anthurium sp. (Thailand), Eucalyptus grandis (South Africa), Gossypium hirsutum (Germany), Leucospermum sp. (USA, Australia), Malus sp. (USA, Mexico, Colombia, Australia); C. nupharicola from Nuphar lutea (USA); C. siamense from Hymenocallis americana (China), Jasminum sambac (Vietnam), Carica papaya (South Africa), Dioscorea rotundata (Nigeria), Malus domestica, Vitis vinifera, Fragaria sp. (USA), Capsicum sp., Mangifera indica (India, Thailand); and C. theobromicola from Acca sellowiana (New Zealand), Theobroma cacao (Panama), Olea europaea, Coffea arabica, Stylosanthes sp. (Australia), Annona diversifolia (Mexico), Mangifera indica (Colombia, India), Limonium sp., Cyclamen persicum (Israel), Fragaria sp., and Quercus sp. (USA)10,11,21,24,27,43,51–54. This indicates the importance of cross-infection potential of different botanical hosts by more than one species of Colletotrichum.

In congruence with previously published studies, the ApMat marker proved to be superior in resolving species within the C. gloeosporioides species complex21,22,24,26,27,42. The Apn2-Mat1-2 locus was first used for delineating populations within the C. graminicola species complex55. The ApMat gene exhibited the following advantages which established it as a promising marker for molecular systematics of the Colletotrichum species complexes: (a) the apn2-Mat1-2 intergenic region is flanked by relatively conserved regions, useful for the design of specific primers, (b) the overall phylogenetic resolution provided by this single marker is more informative than a multigene phylogeny, and (c) the Apmat gene is a highly variable marker which can surpass the problems of gene tree discordance42. In combination with ApMat, gs was also efficient for species resolution within the C. gloeosporioides species complex, as previously observed26.

Pathogenic variability was also observed among the nine representative Colletotrichum species isolates. Pathogenicity assays confirmed that all the nine species cause anthracnose disease in avocado (Table 3). Based on percent disease severity (PDS) calculations, C. aenigma was the most virulent pathogen of avocado in Israel with 92.6 ± 7.7% values. C. perseae sp. nov. emerged as the most dominant pathogen of avocado anthracnose in Israel, occurring in all the sampled areas, totaling 354 of the 538 isolates (65.8%) included in this study. This suggests that C. perseae sp. nov. could be used as a model species for studying population structure and evolution of anthracnose in Israel. Furthermore, the occurrence of the teleomorph in C. perseae sp. nov and C. aenigma species is noteworthy, as no reports of the appearance of the sexual stage have been previously reported, albeit under artificial culture conditions; but may also appear in nature, thus contributing to the genetic diversity of these and other Colletotrichum species. The isolates also exhibited a pattern in geographic distribution (Supplementary Text), C. theobromicola was recovered only from samples collected from Central Israel; C. persea sp. nov. was mainly recovered from samples collected from Central and Northern Israel while C. aenigma was mainly recovered from samples collected from Southern Israel; C. gloeosporioides was mainly recovered from samples collected from Central Israel and C. siamense was mainly recovered from samples collected from the Northern and Southern Israel.

In this study percentage of isolations from different avocado tissues was significantly higher from fruits (94.9%), as compared to green/fresh leaves (19.9%), dry leaves (18%) and green/fresh twigs (10.9%), whereas only a trace percentage originated from dry and dead twigs. This is in contrast to an earlier report56, where large numbers of C. gloeosporioides conidia were produced on dead leaves and infected/mummified fruits in avocado trees in Australia; while minimal numbers were produced on dead twigs and none isolated from branches and green leaves. This may be associated with a dryer environment in certain areas in Australia as opposed to the constant wet, rainy winter season occurring in Israel, when avocado fruits are predominantly harvested. This elevated humidity may contribute to the relatively high percent of infected green and fresh leaves and allow survival of inoculum of the pathogen in the form of quiescent germinated apperssoria in these tissues during the dry summer season prevailing under Israeli cultivation conditions. Similarly, increased rainfall resulted in increased levels of rots in harvested avocados in certain regions of Australia57, and more quiescent infections became established in the temperate regions of South Africa during the rainy part of the year rather than in the dry winter months58,59. While spores of C. gloeosporioides were released from dead leaves entangled in the main canopy60, removal of this material and dead twigs from the canopy did not consistently reduce the numbers of postharvest rots in avocados while the principal means of spread to avocado fruit occurred via rain-borne inocula61. In another report, C. gloeosporioides conidia and perithecia were found in margins of leaf and twig lesions and in the bark from the trunks of trees59. The teleomorph may also occur more commonly in orchards in Israel which has remained unreported, similar to that detected in vitro in plates.

In summary, this work has shed light on aspects of epidemiology of avocado anthracnose in Israel, which may lay the foundation for future studies related to management of the pathogen under field conditions. The diverse genetic structure of the pathogen in Israel, further attests to the probability of the teleomorph existing under field conditions in avocado specifically, and in other economically important crops in general, affected by members of C. gloeosporioides s. l.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

From November 2014 to April 2015, plant samples (fruit, fresh leaves and twigs, dry leaves and twigs) were collected from avocado orchards in the following locations in Israel: Kfar Yuval (Northern Israel), Beit Haemek (Northern Israel), ARO, Bet Dagan (Central Israel), Mikve Israel experimental farm (Central Israel) and Kfar Aza (Southern Israel). Initial samples were collected from plantations of Ettinger and Hass cultivars located in Mikve Israel and ARO, Bet Dagan, (Central Israel). In each orchard, five trees were selected randomly and samples of fruit, leaves (fresh green and dry leaves from the ground) and twigs (fresh green and dry twigs) were collected. During the initial isolation, only 18.6 and 3.4% of Colletotrichum isolates were recovered from dry leaves and twigs, along with other common fungal saprophytes such as Aspergillus and Alternaria; therefore in further samplings from Northern and Central Israel, only fruits, green leaves and green twigs were collected. In Northern Israel (from Kfar Yuval and Beit Haemek), Reed and Hass cultivars were sampled, while in Southern Israel (from Kefar Aza) Hass cultivar was sampled. From each tree five fruits, twigs and leaves of each were sampled. Samples were brought to the laboratory and maintained in a moist chamber at room temperature (20 to 25 °C) and inspected regularly for the appearance of anthracnose symptoms.

Fungal isolation and culture conditions

Anthracnose symptoms were observed after 7–10 days in the collected fruits, leaves and twigs maintained under humid conditions. From each fruit two necrotic disease spots were selected for fungal isolation; while from each twig and leaf, five disks were removed (see below). Colletotrichum strains were isolated from the visible sporulation obtained on fruit lesions using the single spore method62. Isolation from leaves and twigs was performed initially using a tissue isolation method, whereby five sections of 1 cm2 size were cut from each leaf or twig near the infected area, surface sterilized with 70% ethanol for 20 seconds, 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for 3.5 minute, washed with sterile water and dried on sterilized tissue paper. The plant tissue was then placed aseptically on Mathur’s MS semi-selective (M3S) agar medium (per liter composition: 2.5 gm of MgSO4.7H2O, 2.7 gm of KH2PO4, 1 gm of peptone, 1 gm of yeast extract, 10 gm of sucrose and 20 gm of agar), supplemented after autoclaving with iprodione at 2.5 mg/liter (Rovral 50% WP; Rhone Poulenc, France) and 0.1% lactic acid63. Cultures growing from twig and leaf tissue sections were further purified by the single spore method. After 5–7 days, the mycelial growth obtained was transferred onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco, USA) plates, and cultured at 25 °C for morphological characterization. A total of 576 Colletotrichum isolates were recovered, of which morphologically identical isolates were discarded; 538 isolates were used for further characterization (Supplementary Table 1). Percentage occurrence of Colletotrichum isolates from fruit, leaves and twigs was calculated to determine recovery of the pathogen from the different plant parts (Fig. 1).

DNA extraction and assessment of genetic diversity

Single spore cultures of the 538 Colletotrichum isolates were grown at 25 °C in liquid broth of glucose minimal media [GMM, per liter composition: 50 ml of 20 × salt solution (120 gm of NaNO3, 10.4 gm of KCl, 10.4 gm of MgSO4.7H2O, 30.4 gm of KH2PO4 dissolved in one liter of distilled water), 1 ml of Hunter’s trace elements solution, 10 gm of D-glucose, 5 gm of yeast extract, pH 6.5) without shaking and after 7 days fungal mycelia were harvested to isolate DNA64. Ap-PCR was performed using the following primers: (CAG)5, (GACA)4, (AGG)5 and (GACAC)3 14. PCR reactions were conducted in 20 µl volume, containing 1.5 µl of total genomic DNA (50ng/µl concentration), 2 µl of 10x Taq Buffer, 1 µl of 10 µM primer, 2 µl of 25 mM MgCl2, 2 µl of 10 mM dNTPs, 0.2 µl of Taq Polymerase enzyme and 11.3 µl of sterile water. PCR reactions were carried out in a thermocycler (Biometra, Germany) with the following cycling parameters: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 29 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing for 30 seconds (60 °C for CAG and AGG; 48 °C for GACAC and GACA), and extension at 72 °C for 1 minute and 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72 °C for 15 minutes. The PCR amplification and the reaction results were maintained at 4 °C until further processed. The PCR products were separated in 1.8% agarose gel (15 × 10 cm, W × L) in Tris-Acetate-EDTA buffer, at 80 V, 400 mA for 2 hours and stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 µg/ml) to visualize the banding patterns using ENDUROTM GDS gel documenting system (Labnet, USA). PCR reactions were repeated three times with consistent results. Variation based on ap-PCR analysis was not quantified but diversity was interpreted according to overall banding patterns for all the 538 Colletotrichum isolates used in this study (Supplementary Text). Representative isolates of the different groups selected after ap-PCR were then used for sequence based analyses.

PCR amplification and sequencing

Thirty-three representative Colletotrichum spp. isolates were selected according to ap-PCR for multi-locus phylogenetic analyses. PCR amplification of act, cal, gapdh, tub2 and ITS regions was performed for all the isolates. In addition, gs and ApMat were amplified for isolates belonging to the C. gloeosporioides species complex, while chs1 and his3 gene regions were amplified for isolates belonging to the C. boninense species complex. The PCR reactions were carried out as described11,38,42. PCR products were purified with the Gel/PCR DNA fragments extraction kit (Geneaid, Catalogue# DF100, Taiwan), and quantified using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer ND-1000 (Thermo, USA). Purified PCR products were sequenced by Macrogen Europe (http://www.macrogen.com) and submitted to NCBI-GenBank (Tables 1 and 2).

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using the multigene dataset for the C. gloeosporioides species (act, cal, gapdh, ITS, tub2) and C. boninense species complexes (act, cal, chs1, gapdh, his3, ITS, tub2) using reference sequences9,11. In addition, analyses for ApMat marker, gs gene, 2-markers (Apmat, gs), 6-genes (act, cal, gapdh, gs, ITS, tub2) and 7-gene (act, ApMat, cal, gapdh, gs, ITS, tub2) were also performed for the C. gloeosporioides species complex isolates using recently published reference sequences24,26. Reference sequences for the newly described Colletotrichum species within the C. gloeosporioides species complex (C. chengpingense, C. conoides, C. grossum, C. hebeinse, C. helleniense, C. henanense, C. hystricis, C. jiangxiense, C. liaoningense, C. wuxiense) were also added to the dataset31,65,66. Maximum Parsimony (MP) analysis was conducted using PAUP version 4.0b1067. Ambiguous regions within the alignment were removed from the analyses and the gaps were considered as missing data. The trees were inferred using the heuristic search option with Tree Bisection Reconnection (TBR) branch swapping and 20 random sequence additions. Maxtrees were set to 10000, zero length branches were collapsed and all multiple parsimonious trees were saved. In addition, descriptive tree statistics, including tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), rescaled consistency index (RC), and homoplasy index (HI) were recorded. The strength of clades was assessed by a bootstrap analysis with 100 replicates. The resulting trees were viewed using TreeView68 and edited in MEGA version 7.0.1469,70 and Microsoft PowerPoint version 2007. The alignment files and trees were deposited in TreeBase (www.treebase.org; Study ID: 20611). The MP trees generated in this study are shown in Figs 2–4, and Supplementary Fig. 2. Additionally, Maximum likelihood (ML) trees were generated for each dataset using “one click mode” available at the online platform for phylogenetic analysis, www.phylogeny.fr 70. The bootstrap support values generated using two methods (MP and ML) and the resulting tree topologies were also compared (data not shown).

Pathogenicity assays

Pathogenicity assays were performed for representative Colletotrichum spp. isolates (C. aenigma – GA050, C. alienum – GA524, C. fructicola – GA186, C. gloeosporioides – GA070, C. karstii – GA206, C. nupharicola – GA253, C. perseae sp. nov. – GA100, C. siamense – GA331, C. theobromicola – GA002), essentially as described3. Isolates were cultured in M3S agar plates at 25 °C to induce sporulation. After 7 days, conidia were harvested by flooding the culture with 0.85% NaCl (normal saline, with 100 µl/lt Tween 80) and dislodging the conidia with a glass spreader. The conidial solution was filtered through sterile gauze to remove hyphal filaments and concentrated by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed and re-suspended in 1 ml of cold normal saline solution. The conidial concentration was adjusted to a final working concentration of 1 × 107 conidia/ml. Disease free, fresh avocado fruits (Reed and Hass cultivars) were collected from Eyal orchard, Central Israel for pathogenicity assays. Assays were conducted in three replicates containing three fruits each, with two infection sites per fruit. The fruits were surface sterilized using 1% sodium hypochlorite solution, washed and dried using sterile filter paper. Fruits were inoculated with 7 µl of conidial suspension (1 × 107 conidia/ml) at wounded (pin-pricked) and unwounded sites (3 sites per fruit). Control fruits were mock-inoculated with sterile normal saline solution. Inoculated fruits were maintained under humid conditions at 25 °C. The fruits were monitored regularly for the appearance of anthracnose symptoms. Disease severity was scored using the 0–9 point scale65,66,71 at 7 days post inoculation (dpi) and calculations were made as previously described27.

Morphological studies

Morphological characteristics (colony color, growth rate, conidial measurements) were recorded for representative Colletotrichum spp. isolates (C. aenigma – GA050, C. alienum – GA524, C. fructicola – GA186, C. gloeosporioides – GA070, C. karstii – GA206, C. nupharicola – GA253, C. perseae sp. nov. – GA100, C. siamense – GA331, C. theobromicola – GA002) from 7 day old cultures grown on PDA at 25 °C. To enhance sporulation in C. aenigma and C. nupharicola, representative isolates were cultured in M3S agar medium. Ascospores, if present, were recovered from crushed ascomata. Microscopic slides were prepared in lactic acid or water. For each isolate, shape and size of conidia and conidiogenous cells were measured using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy (Olympus U-CMAD3, Japan). At least 30 measurements were made for the length and width of conidia and ascospores via CellB image analysis software (Olympus, Japan). Growth rate was determined by measuring colony diameter after 7 days (mm/day). Morphological characteristics are presented in Table 4.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Gunjan Sharma thanks the Agricultural Research Organization of the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture for the award of a postdoctoral fellowship. We are grateful to Dr. Belle Damodara Shenoy for his invaluable suggestions in editing of this manuscript. We also thank Ms. Hagar Leschner and Dr. Tamar Avin-Wittenberg from the Herbarium of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel for their help in the holotype submission of C. perseae sp. nov.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: G.S., M.M. & S.F. Performed the experiments: G.S. & M.M. Analyzed the data: G.S. & S.F. Prepared tables and figures: G.S. Wrote the paper: G.S. & S.F. This is the first submission of this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15946-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Slot, S. B. Israeli avocado exports in top 10. Fresh Plazahttp://www.freshplaza.com/article/156756/Israeli-avocado-exports-in-top-10 (2016).

- 2.Dor, R. Israel’s avocado industry - Overview. Israeli Agriculture International Portalhttp://www.israelagri.com/?CategoryID=493&ArticleID=1036 (2015).

- 3.Freeman S, Katan T, Shabi E. Characterization of Colletotrichum species responsible for anthracnose diseases of various fruits. Plant Dis. 1998;82:596–605. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bill M, Sivakumar D, Thompson AK, Korsten L. Avocado fruit quality management during the postharvest supply chain. Food Rev. Int. 2014;30:169–202. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2014.907304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean R, et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012;13:414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyde KD, et al. Colletotrichum: a catalogue of confusion. Fungal Divers. 2009;39:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyde KD, et al. Colletotrichum–names in current use. Fungal Divers. 2009;39:147–182. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon PF, Damm U, Johnston PR, Weir BS. Colletotrichum–current status and future directions. Stud. Mycol. 2012;73:181–213. doi: 10.3114/sim0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damm U, et al. The Colletotrichum boninense species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012;73:1–36. doi: 10.3114/sim0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damm U, Cannon PF, Woudenberg JHC, Crous PW. The Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012;73:37–113. doi: 10.3114/sim0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weir BS, Johnston PR, Damm U. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012;73:115–180. doi: 10.3114/sim0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damm U, et al. The Colletotrichum orbiculare species complex: Important pathogens of field crops and weeds. Fungal Divers. 2013;61:29–59. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0255-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey, J.A. & Jeger, M. J. Colletotrichum: biology, pathology and control. (British Society for Plant Pathology, London, 1992).

- 14.Freeman S, Katan T, Shabi E. Characterization of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides isolates from avocado and almond fruits with molecular and pathogenicity tests. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:1014–1020. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1014-1020.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binyamini N, Schiffmann-Nadel M. Latent infection in avocado fruit due to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Phytopathol. 1972;62:592–594. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-62-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prusky, D. & Kotze, J. Postharvest diseases of avocado: Anthracnose. Compendium of Tropical Fruit Diseases. (eds Ploetz, R. C., Zentmyer, G. A., Nishijima, W. T. & Rohrbach, K. G.) 72–73 (APS Press, St. Paul, MN., USA, 1994).

- 17.Nelson, S. Anthracnose of avocado. Co-operative Extension Services (Plant Disease-58, 2008).

- 18.Cai L, et al. A polyphasic approach for studying. Colletotrichum. Fungal Divers. 2009;39:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phoulivong S, et al. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides is not a common pathogen on tropical fruits. Fungal Divers. 2010;44:33–43. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0046-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phoulivong S. Colletotrichum: naming, control, resistance, biocontrol of weeds and current challenges. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. 2011;1:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojas EI, Rehner SA, Samuels GJ. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides s. l. associated with Theobroma cacao and other plants in Panama: multilocus phylogenies distinguish host-associated pathogens from asymptomatic endophytes. Mycologia. 2010;102:1318–1338. doi: 10.3852/09-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle VP, Oudemans PV, Rehner SA, Litt A. Habitat and host indicate lineage identity in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides s. l. from wild and agricultural landscapes in North America. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang F, et al. Colletotrichum species associated with cultivated citrus in China. Fungal Divers. 2013;61:61–74. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0232-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma G, Kumar N, Weir BS, Hyde KD, Shenoy BD. The ApMat marker can resolve Colletotrichum species: a case study with Mangifera indica. Fungal Divers. 2013;61:117–138. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0247-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udayanga D, Manamgoda DS, Liu X, Chukeatirote E, Hyde KD. What are the common anthracnose pathogens of tropical fruits? Fungal Divers. 2013;61:165–179. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0257-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu F, et al. Unravelling Colletotrichum species associated with Camellia: employing ApMat and GS loci to resolve species in the C. gloeosporioides complex. Persoonia. 2015;35:63–86. doi: 10.3767/003158515X687597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma G, Pinnaka AK, Shenoy BD. Resolving the Colletotrichum siamense species complex using ApMat marker. Fungal Divers. 2015;71:247–264. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0312-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calderón C, et al. Species from the Colletotrichum acutatum, Colletotrichum boninense and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complexes associated with tree tomato and mango crops in Colombia. Plant Pathol. 2016;65:227–237. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang L, Li QC, Zhang Y, Li DW, Ye JR. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides sensu stricto is a pathogen of leaf anthracnose on evergreen spindle tree (Euonymus japonicus) Plant Dis. 2016;100:672–678. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-15-0740-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayawardena RS, et al. An account of Colletotrichum species associated with strawberry anthracnose in China based on morphology and molecular data. Mycosphere. 2016;7:1177–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayawardena RS, et al. Notes on currently accepted species of Colletotrichum. Mycosphere. 2016;7:1192–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu X, et al. Colletotrichum species associated with jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) anthracnose in southeastern China. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25179. doi: 10.1038/srep25179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos AP, Talhinhas P, Sreenivasaprasad S, Oliveira H. Characterization of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, as the main causal agent of citrus anthracnose, and C. karstii as species preferentially associated with lemon twig dieback in Portugal. Phytoparasitica. 2016;44:549–561. doi: 10.1007/s12600-016-0537-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhaiem A, Taylor PW. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides associated with anthracnose symptoms on citrus, a new report for Tunisia. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016;146:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-0907-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Silva DD, Ades PK, Crous PW, Taylor PWJ. Colletotrichum species associated with chili anthracnose in Australia. Plant Pathol. 2017;66:254–267. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai L, et al. The evolution of species concepts and species recognition criteria in plant pathogenic fungi. Fungal Divers. 2011;50:121–136. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0127-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu NG, et al. Perspectives into the value of genera, families and orders in classification. Mycosphere. 2016;7:1649–1668. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Damm U, Woudenberg JHC, Cannon PF, Crous PW. Colletotrichum species with curved conidia from herbaceous hosts. Fungal Divers. 2009;39:45–87. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crouch JA. Colletotrichum caudatum s. l. is a species complex. IMA Fungus. 2014;5:1–30. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2014.05.01.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Damm U, O’Connell RJ, Groenewald JZ, Crous PW. The Colletotrichum destructivum species complex - hemibiotrophic pathogens of forage and field crops. Stud. Mycol. 2014;79:49–84. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu F, Cai L, Crous PW, Damm U. The Colletotrichum gigasporum species complex. Persoonia. 2014;33:83–97. doi: 10.3767/003158514X684447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva DN, et al. Application of the Apn2/MAT locus to improve the systematics of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides complex: An example from coffee (Coffea spp.) hosts. Mycologia. 2012;104:396–409. doi: 10.3852/11-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farr, D. F. & Rossman, A. Y. Fungal Databases. U.S. National Fungus Collections, ARS, USDA. https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/ (2017).

- 44.Sharma G, Shenoy BD. Colletotrichum systematics: Past, present and prospects. Mycosphere. 2016;7:1093–1102. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hyde KD, et al. One stop shop: backbones trees for important phytopathogenic genera: I. Fungal Divers. 2014;67:21–125. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0298-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hou LW, Liu F, Duan WJ, Cai L. Colletotrichum aracearum and C. camelliae-japonicae, two holomorphic new species from China and Japan. Mycosphere. 2016;7:1111–1123. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freeman S. Management, survival strategies, and host range of Colletotrichum acutatum on strawberry. HortScience. 2008;43:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossman AY, Palm-Hernández ME. Systematics of plant pathogenic fungi: why it matters. Plant Dis. 2008;92:1376–1386. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-10-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Velazquez-del Valle MG, et al. First report of avocado anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum karstii in Mexico. Plant Dis. 2016;100:534. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-15-0249-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman S, Minz D, Jurkevitch E, Maymon M, Shabi E. Molecular analyses of Colletotrichum species from almond and other fruits. Phytopathol. 2000;90:608–614. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.6.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.James RS, Ray J, Tan YP, Shivas RG. Colletotrichum siamense, C. theobromicola, and C. queenslandicum from several plant species and the identification of C. asianum in the Northern Territory, Australia. Australas. Plant Dis. Notes. 2014;9:138. doi: 10.1007/s13314-014-0138-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schena L, et al. Species of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and C. boninense complexes associated with olive anthracnose. Plant Pathol. 2014;63:437–446. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma G, Shenoy BD. Colletotrichum fructicola and C. siamense are involved in chilli anthracnose in India. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Protect. 2014;47:1179–1194. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2013.833749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma G, Maymon M, Freeman S. First report of Colletotrichum theobromicola causing leaf spot of Cyclamen persicum in Israel. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1790. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-02-16-0208-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crouch JA, Tredway LP, Clarke BB, Hillman BI. Phylogenetic and population genetic divergence correspond with habitat for the pathogen Colletotrichum cereale and allied taxa across diverse grass communities. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:123–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fitzell, R. D. Pre-harvest disease control. Proceedings of the Australian Avocado Growers Federation (Bicentenial Conference, Caloundra, 1988)

- 57.Peterson RA. Susceptibility of Fuerte avocado fruit at various stages of growth, to infection by anthracnose and stem end rot fungi. Anim. Prod. Sci. 1978;18:158–160. doi: 10.1071/EA9780158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darvas JMM, Kotze JM. Avocado fruit diseases and their control in South Africa. South African Avocado Grower’s Association Yearbook. 1987;10:117–119. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darvas JMM, Kotze JM, Wehner FC. Field occurrence and control of fungi causing postharvest decay of avocados. Phytophylactica. 1987;19:453–455. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fitzell RD. Epidemiology of anthracnose disease of avocados. South African Avcoado Grower’s Association Yearbook. 1987;10:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Everett, K. R. Progress in managing latent infections a review. Proceedings from Conference ’97: Searching for Quality (ed. Cutting J. G.). 55–68 (Joint Meeting of the Australian Avocado Grower’s Federation, Inc. and NZ Avocado Growers Association, Inc., 1997).

- 62.Choi YW, Hyde KD, Ho WH. Single spore isolation of fungi. Fungal Divers. 1999;3:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freeman S, Katan T. Identification of Colletotrichum species responsible for anthracnose and root necrosis of strawberry in Israel. Phytopathol. 1997;87:516–521. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.5.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Freeman S, et al. Fusarium euwallaceae sp. nov. – a symbiotic fungus of Euwallacea sp., an invasive ambrosia beetle in Israel and California. Mycologia. 2013;105:1595–1606. doi: 10.3852/13-066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diao Y-Z, et al. Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose disease of chili in China. Persoonia. 2017;38:20–37. doi: 10.3767/003158517X692788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guarnaccia V, et al. High species diversity in Colletotrichum associated with citrus diseases in Europe. Persoonia. 2017;39:32–50. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2017.39.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Swofford, D. L. PAUP*: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony, version 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. http://paup.csit.fsu.edu (2003).

- 68.Page, R. D. M. TREEVIEW: Tree drawing software for Apple, Macintosh and Microsoft Windows. Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow. Glasgow, Scotland, UK. (1996).

- 69.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dereeper A, et al. Phylogeny. fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Montri P, Taylor PWJ, Mongkolporn O. Pathotypes of Colletotrichum capsici, the causal agent of chili anthracnose, in Thailand. Plant Dis. 2009;93:17–20. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-93-1-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.