Abstract

Background

General practitioners play a key role in the care of patients with depressive disorders. We studied the frequency and type of treatment of depressive disorders in primary care.

Methods

In a cross-sectional epidemiological study on a particular day in six different regions in Germany, 253 physicians and 3563 unselected patients were asked to fill in a questionnaire assessing the diagnosis and treatment of depression. A total of 3431 usable patient data sets and 3211 sets of usable data from both the patient and the physician were subjected to further analysis.

Results

68.0% of the 490 patients in primary care who were classified as depressed according to the Depression Screening Questionnaire received treatment from their general practitioner or in other care settings; the probability of being treated by the general practitioner was higher for patients whose diagnosis was recognized by the general practitioner (92.8%) than for the remaining depressed patients (47.8%). On the day of data recording, 54.1% of the depressed patients were under treatment by the general practitioner and 21.2% had been referred to specialized treatment. Approximately 60% of the depressed patients were not being treated, as recommended in the guidelines, with antidepressant drugs, psychotherapy, or both. The likelihood of being treated in conformity with the guidelines depended on whether or not the general practitioner had made the diagnosis of depression (odds ratio [OR] = 7.5; 95% confidence interval = [4.9; 11.6]; p <0,001); it was also higher if the general practitioner had an additional qualification in psychotherapy (OR = 1.9; [1.1; 3.4]; p = 0.022).

Conclusion

The finding that a relevant proportion of patients with depressive disorders in primary care are inadequately treated indicates the need to improve general practitioners’ ability to diagnose these conditions and determine the indication for treatment.

Depression is one of the most commonly occurring mental disorders (1) and is associated with considerable individual and social costs (2, 3). Early detection and effective treatment of depression are thus of major importance. Quality-assured standards have been established for the diagnosis and optimal management of depression (S3 guideline/national care guideline for unipolar depression) (4– 6). Nevertheless, a high proportion of patients still do not receive adequate treatment (7), with correct recognition of the disorder being among the most important predictors of guideline-oriented therapy (8, 9).

Primary care physicians play a key role in the care of patients with depression. They are usually the point of first contact with the healthcare system and can detect depression at an early stage, decide whether to initiate treatment themselves or refer the patient to a specialist; they therefore pave the way for treatment according to the guidelines (10– 12).

Recent findings on the frequency and quality of treatment of patients with depression by primary care physicians in German-speaking countries are based on secondary data analyses (7, 10) that provide no information about the considerable proportion of people with depression whose disorder is not detected or diagnosed. The most recent epidemiological survey of depression in the area of primary care in Germany took place at the end of the 1990s in the context of the Depression 2000 study, which found—together with a high prevalence of depression on the reference date— room for improvement in the detection and treatment of depressive disorders (13, 14). We therefore decided to conduct again an epidemiological study to obtain up-to-date information on the treatment of patients with depression in the primary care setting following the publication of the S3 guideline.

Methods

Study design and sample

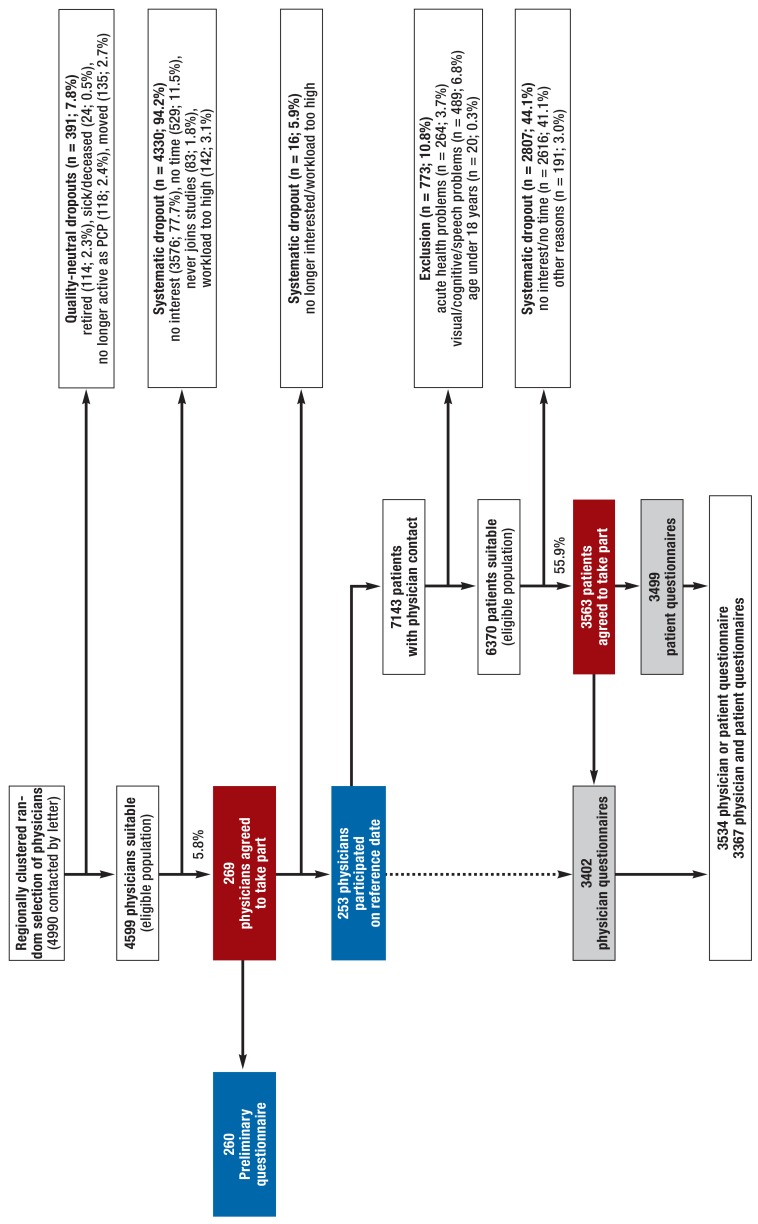

Late in 2013 and early in 2014, within the framework of a nationwide epidemiological study program into the treatment of depression in the primary care setting (the VERA study) and on the basis of a regionally clustered random selection of primary care physicians in six regions of Germany, 269 such physicians (response rate 5.8%) were recruited to participate in the study. In a preliminary study, they first had to provide information about themselves and their offices. Subsequently, 253 doctors with 3563 unselected patients (response rate 55.9%) participated in the cross-sectional survey on the reference date by filling in a patient or physician questionnaire. This resulted in 3431 evaluable patient questionnaires. For 3367 patients both questionnaires had been completed, and in 3211 cases both were suitable for analysis. This sample formed the basis for the greater part of the results presented here. Details of study conduct and the samples of physicians and patients can be found in the eMethods and in eFigure 1.

eFigure 1.

Flowchart of recruitment and response;

PCP, primary care physician

Documentation of depression

Symptoms of depression were self-reported by the patients by means of the Depression Screening Questionnaire (DSQ) (15). The DSQ comprises 12 questions about symptoms during the foregoing 2 weeks designed to ascertain whether the ICD-10 criteria of depressive episodes (16) are fulfilled. The ICD-10 study diagnosis “depression” was coded if four or more symptoms were endorsed, including at least three present “on most days” (17) (ebox). According to these criteria, n = 490 patients (14.3%) had depression (including n = 451 [14.1%] for whom a physician questionnaire had been completed).

eBOX. Documentation of depression.

The patients documented their own symptoms of depression by completing the Depression Screening Questionnaire (DSQ [15]), which was used as an approximate quality standard in the current study. The DSQ was developed on the basis of the standardized Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI [34–36]) and comprises 12 questions designed to ascertain whether the ten ICD-10 criteria of depressive episodes (16) are fulfilled. The frequency with which these symptoms have occurred during the preceding 2 weeks is reported (0 = not at all, 1 = sometimes, 2 = on most days). The DSQ has been found to have good test-retest reliability for symptoms and diagnosis (0.68–0.92); validity for the diagnosis of major depression has also been shown (kappa = 0.76) (15). In the context of the diagnostic validation study embedded in the VERA study program, there was very high correlation between the DSQ data and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9 [37]) (r = 0.83, n = 2911), an instrument widely applied across the world for depression screening, and the classification performance resembled that of 12-month diagnosis of ICD-10 depression by means of standardized interview (CIDI) (AUC = 0.604 for both the DSQ ICD-10 algorithm and the PHQ-9 DSM-IV algorithm).

As in the Depression-2000 study (17), the data of all patients who answered at least one of the questions in the DSQ were included in analysis; missing data were classified as absence of the corresponding symptom of depression. In accordance with the ICD-10 assessment algorithm, a study diagnosis of “depression” was coded if at least three symptoms were present “on most days” and the total score exceeded 7, i.e., at least four symptoms had to be present overall.

-

The severity of depression detected using the DSQ was classified as follows:

-

Mild: at least three symptoms “on most days,” total score = 8

(i.e., at least four symptoms had to be present overall)

-

Moderate: at least five symptoms “on most days,” total score = 12

(i.e., at least six symptoms had to be present overall)

-

Severe: at least seven symptoms “on most days,” total score = 16

(i.e., at least eight symptoms had to be present overall)

In addition, the physicians assessed the current and previous presence of depression after the consultation for each patient seen on the reference date (physician’s diagnosis).

-

-

The physicians classified the depression as follows:

Definite = patient clearly depressed, all criteria fulfilled

Subthreshold = patient clearly depressed, but not all criteria fulfilled

Questionable = patient not necessarily depressed, could have a different syndrome

Absent = patient clearly not depressed (physician’s diagnosis)

The presence of other mental disorders was documented in the same way. If depression was diagnosed, the physician also jugdged its severity (mild, moderate, severe).

Furthermore, the physicians assessed the presence of depression and other mental disorders and classified them as “definite,” “subthreshold,” “questionable,” or “absent.” If depression was diagnosed, its severity was estimated.

Documentation of treatment

Both the physicians and their patients were asked about the treatment of depression (etable 1). In the physician questionnaire, the doctors gave an account of their interventions on the study day (reference date) together with any existing ongoing treatments. The patients were asked to document current treatments. Thus, we describe the treatment given by the physician on the reference date (data from the physician questionnaire) (table) and any existing treatments beyond that received on the reference date (data from the physician and patient questionnaires) (etable 2). Just as in previous studies (18), the data provided by the physicians and by the patients were somewhat divergent (Cohen’s kappa 0.20–0.40). In order to ensure maximum sensitivity in identification of treatments, all treatments were assumed if they were mentioned by either the patient or by the doctor (19, 20).

eTable 1. Documentation of interventions/treatments.

| Physician questionnaire | |

| Procedure/treatment on reference date | ● Nothing done/no intervention needed ● Initially no action, repeat visit (corresponding to active waiting) ● Referral for specialist care (psychiatrist, psychotherapist, inpatient, other) ●Treatment (discussion/consultation, psychotherapy, medication) |

| Existing ongoing treatments | ● Psychiatric/drug treatment – Ongoing treatment by psychiatrist – Inpatient treatment – Antidepressants – Other medication ● Psychotherapy – Ongoing – Inpatient ● Discussion/consultation ● Other (free description) |

| Type of medication (prescribed by primary care physician or, in context of ongoing treatment, by specialist) |

● Antidepressants – Tri-/tetracyclics (TCA) – Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) – Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSA) – Selective serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRI) ● Other medications ● Hypnotics/sedatives ● Neuroleptics/antipsychotics ● Phytotherapeutics ● Other (free description) |

| Patient questionnaire | |

| Current treatments | ● Medication ● Discussion ● Psychotherapy ● Other (free description) |

| Categorization for assessment of guideline adherence | |

| (1) Psychotherapy | ● Psychotherapeutic treatment by primary care physician on reference date ● Referral to psychotherapist or for inpatient care initiated by physician or reported as ongoing ● Statement of currently ongoing psychotherapy by physician or patient |

| (2) Antidepressants | ● Treatment on reference date or currently ongoing treatment (as stated by physician) with following substances: TCA, SSRI, NaSSA, SSNR ● Referral to psychiatrist or for inpatient care initiated by physician or reported as ongoing |

| (3) Other treatments | ● Consultation, discussions (statements by physician and patient regarding reference date and ongoing treatments) ● Treatment with hypnotics/sedatives, neuroleptics/antipsychotics, and/or phytotherapeutics (statements by physician regarding reference date and ongoing treatments) or unspecific information about drug treatment (statement by patient) ● Treatments other than those mentioned above (statements by physician and patient) |

| (4) No treatment | ● None of the interventions in categories (1), (2), and (3) mentioned by either physician or patient |

Table. General practitioner interventions on the reference date*1.

| Depression (definite) diagnosed by physician*2 | DSQ study diagnosis*3 | DSQ cases diagnosed by physician as depression (definite/subthreshold)*3 | DSQ cases diagnosed by physician as other mental disorder (incl. questionable diagnoses)*3 | |||||||||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | |

| n = 86 | n = 208 | n = 33 | n = 353 | n = 280 | n = 117 | n = 54 | n = 451 | n = 119 | n = 64 | n = 38 | n = 221 | n = 67 | n = 28 | n = 9 | n = 104 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| No intervention | 20.9 | 12.5 | 3.0 | 13.6 | 45.5 | 35.5 | 21.8 | 40.1 | 19.3 | 14.1 | 10.5 | 16.3 | 38.8 | 39.3 | 22.2 | 37.5 |

| No intervention needed | 20.9 | 10.1 | 3.0 | 12.2 | 43.8 | 32.2 | 20.0 | 38.0 | 17.6 | 12.5 | 10.5 | 14.9 | 35.8 | 28.6 | 22.2 | 32.7 |

| No initial treatment/repeat visit (active waiting) | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 4.8 |

| Treatment | 76.7 | 82.2 | 93.9 | 82.2 | 49.3 | 57.9 | 70.9 | 54.1 | 79.0 | 82.8 | 81.6 | 80.5 | 59.7 | 53.6 | 77.8 | 59.6 |

| Discussion/consultation | 61.6 | 64.9 | 84.8 | 65.4 | 41.4 | 48.8 | 56.4 | 45.1 | 67.2 | 71.9 | 63.2 | 67.9 | 52.2 | 42.9 | 66.7 | 51.0 |

| Psychotherapy | 2.3 | 7.7 | 15.2 | 7.4 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 12.7 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 15.8 | 7.2 | 4.5 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 6.7 |

| Medication | 44.2 | 56.7 | 81.8 | 55.2 | 25.5 | 34.7 | 47.3 | 30.5 | 44.5 | 57.8 | 60.5 | 51.1 | 22.4 | 14.3 | 33.3 | 21.2 |

| – Antidepressants | 33.7 | 42.8 | 75.8 | 42.8 | 17.2 | 23.1 | 32.7 | 20.6 | 32.8 | 43.8 | 39.5 | 37.1 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 9.6 |

| – SSRI/SSNRI/NaSSA | 23.3 | 30.8 | 45.5 | 29.7 | 9.7 | 14.9 | 18.2 | 12.0 | 19.3 | 28.1 | 21.1 | 22.2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 3.8 |

| – TCA | 4.7 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| – Not specified | 5.8 | 7.2 | 24.2 | 8.5 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 12.7 | 5.4 | 7.6 | 9.4 | 15.8 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 3.8 |

| – Other substances | 11.6 | 25.5 | 39.4 | 22.7 | 12.1 | 17.4 | 29.1 | 15.5 | 21.0 | 25.0 | 39.5 | 25.3 | 11.9 | 14.3 | 11.1 | 12.5 |

| – Hypnotics/sedatives | 1.2 | 4.8 | 18.2 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 7.3 | 3.4 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 10.5 | 5.9 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| – Neuroleptics | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 1.0 |

| – Phytotherapeutics | 3.5 | 7.7 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 7.9 | 5.9 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| – Other | 7.0 | 11.5 | 18.2 | 11.0 | 5.2 | 9.9 | 18.2 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 12.5 | 23.7 | 12.2 | 6.0 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 7.7 |

| Referral | 15.1 | 38.0 | 60.6 | 34.0 | 16.6 | 23.1 | 41.8 | 21.2 | 24.4 | 37.5 | 52.6 | 33.0 | 22.4 | 14.3 | 33.3 | 21.2 |

| Psychiatrist | 9.3 | 22.6 | 33.3 | 20.1 | 6.2 | 14.0 | 27.3 | 10.7 | 9.2 | 21.9 | 34.2 | 17.2 | 9.0 | 10.7 | 22.2 | 10.6 |

| Psychotherapist | 4.7 | 15.9 | 33.3 | 14.2 | 6.6 | 9.1 | 27.3 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 15.6 | 36.8 | 15.8 | 11.9 | 3.6 | 11.1 | 9.6 |

| Inpatient | 1.2 | 3.4 | 15.2 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| Other | 1.2 | 3.4 | 9.1 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

DSQ, Depression Screening Questionnaire; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; NaSSA, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants; SSNRI, selective serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

*1The physician’s diagnosis is determined from the physician questionnaire (assessment of presence of depression or another mental disorder) and classified as follows: definite = clear-cut depression fulfilling all criteria; subthreshold = clear-cut depression, but not all criteria fulfilled; questionable = not obviously depression (could be another syndrome). The DSQ study diagnosis is determined from the patient questionnaire. The intervention is determined from the physician questionnaire. All interventions on the reference date were included (multiple answers were possible).

*2 Severity as assessed by physician; some data were missing, so the numbers n for the three categories of depression do not add up to the total n.

*3 Severity as determined by means of DSQ

eTable 2. Existing ongoing treatments*1.

| Depression (definite) diagnosed by physician*2 | DSQ study diagnosis*3 | DSQ cases diagnosed by physician as depression (definite/subthreshold)*3 | DSQ cases diagnosed by physician as other mental disorder (incl. questionable diagnoses)*3 | |||||||||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | |

| n = 86 | n = 208 | n = 33 | n = 353 | n = 300 | n = 130 | n = 60 | n = 490 | n = 119 | n = 64 | n = 38 | n = 221 | n = 67 | n = 28 | n = 9 | n = 104 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Treatment of any kind*4 | 79.1 | 78.8 | 90.9 | 79.9 | 49.3 | 55.4 | 71.7 | 53.3 | 74.8 | 71.9 | 84.2 | 75.6 | 35.8 | 46.4 | 55.6 | 40.4 |

| Discussion*4 | 26.7 | 39.4 | 57.6 | 37.1 | 21.0 | 31.5 | 31.7 | 25.1 | 37.8 | 43.8 | 44.7 | 40.7 | 11.9 | 17.9 | 11.1 | 13.5 |

| Psychotherapy*4 | 22.1 | 34.6 | 54.5 | 34.8 | 20.3 | 23.1 | 41.7 | 23.7 | 32.8 | 29.7 | 52.6 | 35.3 | 14.9 | 14.3 | 22.2 | 15.4 |

| Drug/psychiatric treatment*4 | 57.0 | 59.6 | 75.8 | 60.1 | 32.3 | 40.0 | 48.3 | 36.3 | 50.4 | 56.3 | 57.9 | 53.4 | 22.4 | 25.0 | 44.4 | 25.0 |

| – Antidepressants*5 | 27.9 | 31.7 | 51.5 | 32.0 | 11.4 | 15.7 | 18.2 | 13.7 | 25.2 | 28.1 | 23.7 | 25.8 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 11.1 | 2.9 |

| – SSRI/SSNRI/NaSSA | 23.3 | 27.4 | 48.5 | 28.0 | 8.6 | 14.9 | 14.5 | 11.3 | 19.3 | 26.6 | 18.4 | 21.3 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 11.1 | 2.9 |

| – TCA | 4.7 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| – Other medications*5 | 9.3 | 13.9 | 9.1 | 11.9 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 12.7 | 6.2 | 10.9 | 7.8 | 18.4 | 11.3 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| – Hypnotics/sedatives | 4.7 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 3.6 | 2.2 | 5.0 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| – Neuroleptics | 1.2 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| – Phytotherapeutics | 3.5 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| – Other | 1.2 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 13.2 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Other*4 | 3.5 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 4.0 | 8.5 | 23.3 | 7.6 | 4.2 | 15.6 | 31.6 | 12.2 | 7.5 | 3.6 | 11.1 | 6.7 |

DSQ, Depression Screening Questionnaire; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; NaSSA, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants; SSNRI, selective serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

*1 Ongoing treatments: all treatments stated by physician or patient on reference date to be already taking place (not including interventions by the physician on the reference date). The table is based on data from physician and patient questionnaires.

*2 Severity as assessed by physician; some data were missing, so the numbers n for the three categories of depression do not add up to the total n.

*3 Severity as determined by means of DSQ

*4 Mentioned by physician or patient

*5 Mentioned by physician (only if physician questionnaire completed; therefore, number n deviates from the other data).

Adherence to guidelines

To facilitate estimation of the extent to which treatment adhered to the guidelines, all measures mentioned were assigned to one of the following categories: (1) psychotherapy, (2) antidepressants, (3) other treatment, (4) no treatment (etable 1). Interventions on the reference date and any ongoing treatments were included. According to the S3 guidelines, both psychotherapy and antidepressants are indicated for the treatment of depression.

Statistical analysis

Frequency analyses were used to report physicians’ intervention behavior when they diagnosed depression, independent of the results of the DSQ (physician’s diagnosis “definite depression,” n = 353 [10.7%]). In addition, physicians’ interventions in patients with the ICD-10 DSQ study diagnosis of depression were investigated. In all analyses that included data provided by the physicians, the investigation sample comprised those patients for whom both DSQ data and diagnostic information in the physician questionnaire were present (n = 3211). Individual analyses that include only data provided by patients relate to the sample of 3431 patients.

Analyses of treatment were stratified according to the detection of depression by the primary care physician. The physician classified the DSQ cases as definite/subthreshold depression (correct detection) or as questionable depression or questionable/subthreshold/definite other mental disorder (unspecific case detection) (efigure 2). Furthermore, in each case stratification according to the severity of depression was carried out. To identify physician characteristics (= independent variables) associated with guideline-adherent treatment (= dependent variables), we performed logistic regression analyses and determined the odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. As physician characteristics, age, sex, additional qualification in psychotherapy, additional qualification in basic psychosomatic care, and self-reported familiarity with the S3 guideline were included. Because several patients were recruited in each participating office, we made allowance for possible cluster effects in the logistic regressions by means of robust standard errors.

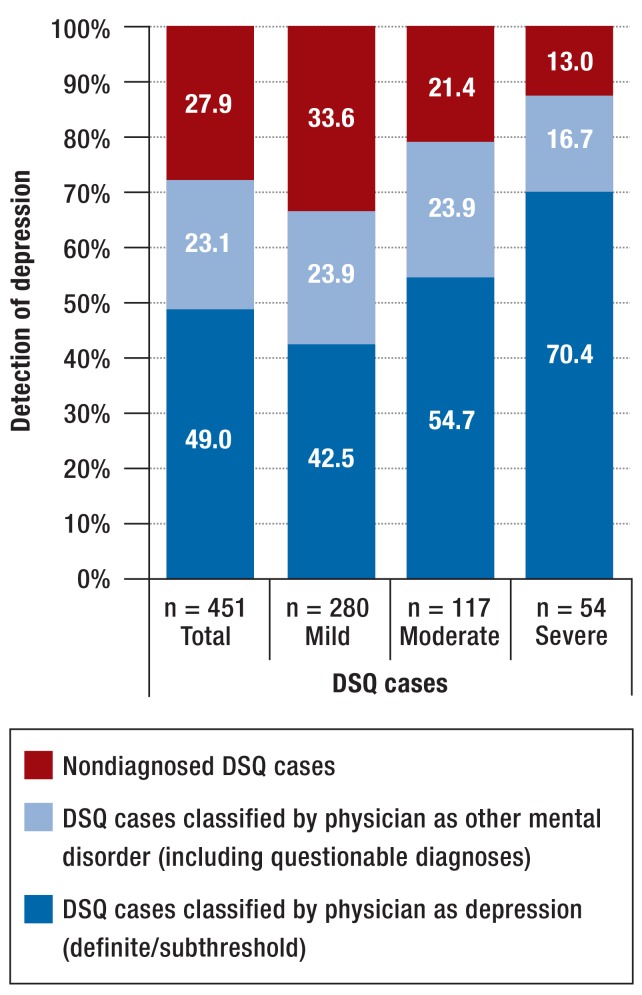

eFigure 2.

Classification of DSQ cases by physician;

DSQ, Depression Screening Questionnaire

Results

Incidence and types of treatment on the reference date

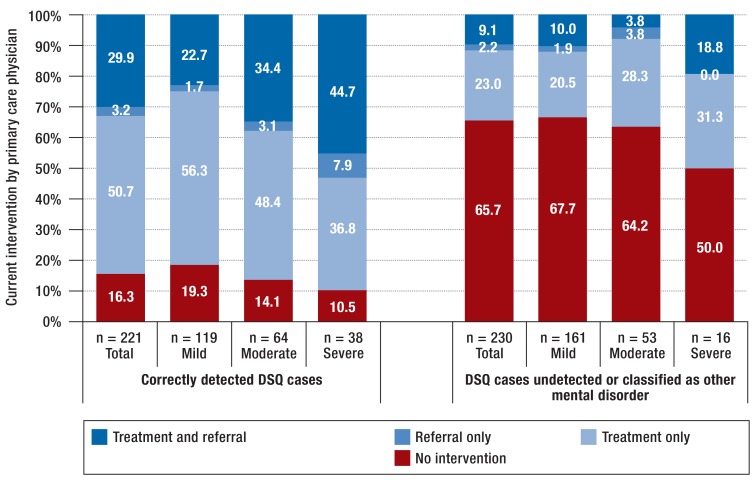

Active waiting with a repeat visit was extremely rare on the reference date (three patients among all cases of depression detected by the physicians, none of them initially diagnosed on the reference date) (table). In the majority of cases the physician provided treatments on the reference date, regardless of whether the patient fulfilled the diagnostic criteria according to the information they supplied themselves or as assessed by the physician. The most commonly occurring interventions were discussions/consultations, followed by drug treatment. A small proportion of the physicians carried out psychotherapy themselves (mild depression: 2.3 to 5.9%; moderate depression: 4.7 to 12.0%; severe depression: 12.5 to 15.8%). Depending on depression diagnosis (self-reported or diagnosed by the physician) and on depression severity, the proportion of patients referred for specialist care varied between 15.1% and 60.6%. In the majority of referrals, the primary care physician continued to be involved in the patient’s treatment (figure 1). Both for patients treated by the primary care physician and for those referred to specialists, detection of depression by the primary care physician—compared with nondetection or assignment of another diagnosis—was associated with a higher probability of the respective intervention by the primary care physician on the reference date.

Figure 1.

Treatment and referral by the primary care physician depending on his/her detection of depression (DSQ study diagnosis); DSQ, Depression Screening Questionnaire

Incidence and types of previous treatments

For 53.3% of patients with a diagnosis of depression according to the DSQ and 79.9% of those with a corresponding diagnosis from a physician, ongoing treatment was stated by the physician or the patient on the reference date (etable 2). Ongoing drug treatment was found more frequently than psychotherapy. Psychotherapy was reported for 23.7% of the DSQ cases and 34.8% of the physician-diagnosed cases. The most frequently specified medications were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), selective serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRI), and noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSA). Treatment with tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and substances other than antidepressants was infrequently mentioned. For most interventions, the likelihood of treatment increased with the severity of the depression and with the physician’s detection of depression reported by the patient in the questionnaire.

Adherence to guidelines

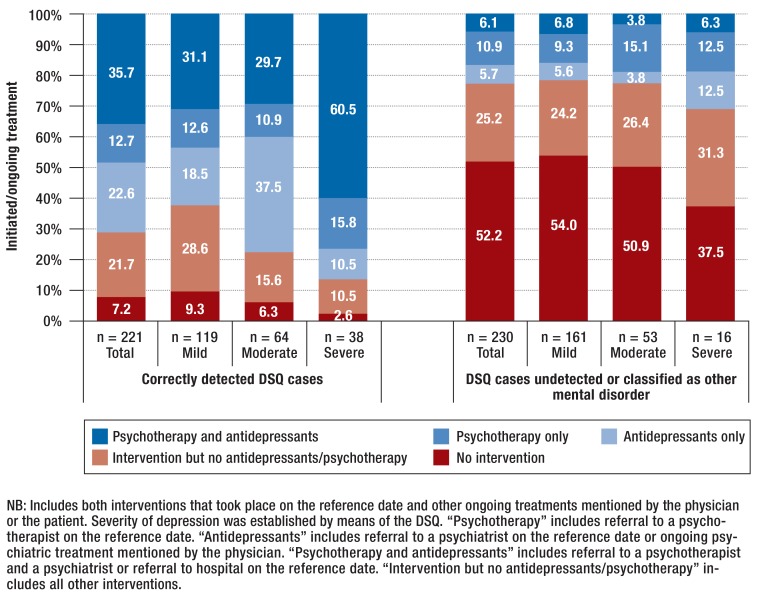

Figure 2 shows the proportions of patients with guideline-oriented treatment (psychotherapy and/or antidepressants), other treatment (intervention, but no antidepressants or psychotherapy), and no treatment. Both interventions on the reference date (including referral to a psychiatrist, a psychotherapist, or a hospital) and ongoing treatments are included. Among correctly detected DSQ cases, the proportion without any intervention was low (from 2.6% for severe depression to 9.3% for mild depression). In cases of depression not detected by the physician or diagnosed by other means, the corresponding figures were 37.5% for severe depression and 54.0% for mild depression. Overall, 68.0% of DSQ cases received an intervention on the reference date, either at the hands of the primary care physician or in other care settings. There were indications of undertreatment as defined by the S3 guideline (no antidepressants or psychotherapy in mild or moderate depression, no combination treatment in severe depression) in 58.6% of the DSQ cases overall, but the rate was lower in correctly detected DSQ cases (33.5%) than in undetected cases (79.1%; OR = 7.5 [4.9; 11.6]; p <0.001). The most pronounced signs of undertreatment were found for severe depression (60.0% overall, 39.5% if detected, 93.7% if not detected). The 37.9% rate of undertreatment in undetected mild depression did not decrease when physicians’ data on active waiting with a repeat visit were taken into account.

Figure 2.

Extent of adherence to treatment guidelines depending on detection of depression (DSQ study diagnosis) by the primary care physician; DSQ, Depression Screening Questionnaire

More female than male physicians dispensed treatment in accordance with the guidelines (OR = 1.64 [1.04; 2.60]; p = 0.034). The physicians’ age made no difference in this respect. Moreover, patients with depression were more likely to be treated according to the guidelines by physicians with an additional qualification in psychotherapy (55.8%) than by those with no such qualification (39.7%; OR = 1.9 [1.1; 3.4]; p = 0.022). This did not apply to an additional qualification in basic psychosomatic care (OR = 1.04 [0.66; 1.62]; p = 0.862). Self-reported familiarity with the S3 guideline showed a tendency towards association with guideline-adherent treatment of patients with depression (OR = 1.5 [0.98; 2.3]; p = 0.058).

Discussion

The main findings of this cross-sectional epidemiological investigation into the frequency and nature of treatment of patients with depression in primary care are the following:

The majority of primary care patients with depression received treatment/intervention of some kind.

According to a survey carried out on a reference date, approximately half of the patients with depression are treated by the primary care physician themselves, while around one fifth are referred to specialist care.

Primary care patients with depression were more likely to receive pharmacological treatment than psychotherapy. This was also true for those with mild depression.

Indications of undertreatment are found in more than half of primary care patients with depression, in that they did not receive antidepressants or psychotherapy as recommended in the relevant guidelines. Treatment according to the guidelines depended strongly on correct detection of the depression by the primary care physician and was more likely if the latter had an additional qualification in psychotherapy.

The rates of treatment for depression in primary care in this study are relatively high compared with both the general population (11) and health insurance data (21). Almost all patients in whom the primary care physician diagnoses depression receive some kind of treatment. Together with the introduction of the S3 guideline, the reason for the high treatment rates may be heightened awareness of mental disorders in general and depression in particular.

The involvement of primary care physicians in the treatment of depressed patients is also relatively high. In 80% of the cases of depression they detect, they carry out the treatment themselves. This is a slightly higher proportion than was found in a similar study at the turn of the century (12) and corresponds with more recent health insurance data (10). In detected cases of depression, physicians treat just over a third of patients with antidepressants, independent of disease severity. A noteworthy aspect is the sharp decrease in the use of TCA from around 32% in 2000 (12) to approx. 0 to 6% in our study. As could be expected, the proportion of psychotherapeutic interventions in primary care is small, although much higher in severe depression. Shortages in the provision of specialized care may be relevant, leading suitably qualified primary care physicians to decide to offer psychotherapy themselves.

Along with interventions by the primary care physicians, the majority of patients with depression showed indications of further ongoing treatments where pharmacological treatment was found more frequently than non-medicinal interventions. This is in agreement with health insurance data (22) and was also found for mild depression, which suggests that the S3 guideline’s recommended preference of psychotherapy over medication for mild depression has not yet been widely adopted. In this respect, some authors have already pointed to possible overmedication in the treatment of mild depression (23), although the findings are inconsistent (7). It may be that the limited psychotherapy resources tend to be reserved for severe cases of depression. With regard to the other ongoing drug treatments, as in primary care, TCA and non-antidepressant medication were rarely prescribed. This indicates good implementation of the S3 guideline with respect to the use of effective and ideally well-tolerated substances.

Assessment of adherence to the guidelines showed that as many as around 70% of patients with depression correctly diagnosed by primary care physicians receive either psychotherapy or treatment with antidepressants. In undetected cases (other or no diagnosis), however, the proportion was barely one quarter. Such a large discrepancy cannot be explained exclusively by treatment by the primary care physician; rather, it points to a central role of primary care physicians as “gatekeepers,” not only treating patients themselves but in particular also initiating necessary treatments by referring patients elsewhere. This requires efficient detection of depression. Although combined treatment with psychotherapy and antidepressants, as advised in the guidelines, is used more often in severe depression than in mild and moderate depression, less than two thirds of patients with severe depression are treated in this way. In this respect, implementation of the guideline is not yet satisfactory. However, no conclusions can be drawn here about the reasons (e.g., failure to recognize the indication or refusal by the patient).

Limitations

The limitations of this study have to be considered when interpreting its findings. This was a cross-sectional investigation. Data on the course of the disorder and its treatment could not be taken into account. Because the survey took place on one particular day, not all primary care interventions could be recorded. The presented frequencies of interventions by the primary care physicians are conservative estimates. On the other hand, the use of statements from both the physicians and their patients in estimating ongoing treatments tends to result in overestimation of treatment rates. Confirmation of the treatment data, e.g., by comparison with health insurance data, was not possible in this study. Assessment of guideline adherence can be estimated only roughly, because numerous aspects (duration, dosage, change of treatment) could not be taken into account. Furthermore, questions on overtreatment of mild and moderate depression cannot be answered by means of these cross-sectional data. Although the DSQ is based on established diagnostic criteria (16, 24) and possesses good sensitivity and specificity, the method has limitations regarding the correct classification of patients with depression and can by no means be viewed as the gold standard (25– 29). This must be considered particularly with regard to “detected cases.”

As in other recent studies (30, 31), the response rate among the physicians was relatively low. The sample of physicians is characterized by high proportions of female physicians and young doctors compared with figures on all non-hospital physicians registered in Germany in 2014 (eMethods, eFigure 1).

Summary

The results of this primary care study show that a high proportion of patients with depression receive treatment or an intervention of some kind. The treatment of depression in general and adherence to the prevailing guidelines in particular depends largely on correct diagnosis by the family doctor. Our findings underline the importance of primary care physicians in the management of depression as well as the need for training of medical students and young doctors in the diagnosis of depression and the indications for various forms of treatment. A disease management program for depression could help to reduce the rate of undertreatment (32, 33).

Key Messages.

The majority of primary care patients with depression receive an intervention of some kind, but only 40% are treated according to the guidelines.

A high proportion of patients with depression are treated by their primary care physician, with medication outweighing non-medicinal interventions.

It is necessary to train medical students and primary care physicians in the diagnosis of depression and the indications for various forms of treatment in order to ensure that depression is treated according to the prevailing guidelines.

eMETHODS

Supplementary informationen about the VERA study

The nationwide multistage epidemiological study program on the treatment of depression in primary care settings in Germany (the VERA study) comprises a preliminary study, a main study with a cross-sectional (reference date) and a longitudinal component (follow-up surveys after 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months), two embedded add-on studies (a cluster-randomized intervention study and a diagnostic validation study), and a health-economics evaluation component. The study protocol was reviewed by the ethics board of TU Dresden (EK-392102013). The present article refers to the cross-sectional reference date survey, together with data from the preliminary study.

Sample of physicians and preliminary study

On the basis of a regionally clustered random selection of physicians engaged in primary care from the physicians’ directory, in late 2013 and early 2014 we sent letters to doctors in six regions of Germany (Berlin, Dresden, Fulda/Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Munich), stratified by location (city, town, rural). In these letters, the physicians were informed about the aim of the study and how it would be carried out and asked to participate. Recruitment of physicians was supported by personal visits and telephone calls from regional study coordinators/monitors (members of the Regional Alliances Against Depression and students/ scientific assistants involved in the study). The target was recruitment of 300 physicians.

Altogether, letters were sent to 4990 physicians, 391 of whom were registered as quality-neutral dropouts (e.g., retirement, sickness/death, moved away) (efigure 1). Of the remaining 4599 physicians, 269 gave their written agreement to take part in the study (response rate 5.8%). Two hundred sixty of these provided sufficient information in a preliminary questionnaire with details about themselves and the nature of their offices, their attitudes towards depression and its treatment, and their opinions on the acceptance and implementation of the S3 guideline. Each physician who completed the six-page questionnaire received € 10.

The mean age of the physicians who took part in the study was 52.0 years (standard deviation [SD] 8.8, range 26–79, 36.6% <50 years), and 53.9% were female. Similarly to the age and gender structure of the primary care physicians registered in medical associations across Germany in 2014 (according to the Federal Health Report), the VERA sample of physicians is characterized by a comparably high proportion of women (VERA: 53.9 female; nationwide: 43.4% female) and a high number of young doctors (VERA: 36.6% <50 years; nationwide: 29.4% <50 years). Almost one quarter (23.5%) of the physicians stated that they had worked in a psychiatric facility. Overall, the participants had been working as primary care physicians in Germany for an average of 15.1 years (SD 9.4, range 0–45 years). A small proportion of them possessed an additional qualification in psychotherapy (5.5%) or were training in psychotherapy (2.4%); the majority had an additional qualification in basic psychosomatic care (74%, with a further 2.4% in training).

The physicians reported seeing a mean of 39.2 patients/day (median 40, range 5 to 90) and spending 11 min on each patient (SD 3.9, median 10). The participants’ estimation of their competence in detection and diagnosis of depression was predominantly positive (good 68.6%, moderate 31.4%, poor 0%), but they rated their competence in drug treatment somewhat less highly (good 36.4%, moderate 53.9%, poor 9.7%). Competence in psychotherapy was stated as good by 23.6% of the physicians, as moderate by 43.2%, and as poor by 33.2%.

Most of the physicians who took part in the study considerd guidelines to be generally helpful in their daily work (full agreement 33.1%, partial agreement 49.8%; disagreement 17.1%). The 41% of the physicians who stated they knew the S3 guideline on unipolar depression estimated their familiarity with it on a scale ranging between 0 and 100%; the average figure was 54.4% (SD = 24.7). Knowledge of the S3 guideline was independent of the physicians’ age or their possession of an additional qualification in basic psychosomatic care, but tended to be greater among those with an additional qualification in psychotherapy (55.6% for physicians with the qualification or training for it vs. 40.0% for those without the qualification) and in those who had attended at least one course related to depression in the previous 2 years (43.7% vs. 33.3% for physicians who had not attended such a course in the same period). One third (33.7%) of the physicians with self-reported knowledge of the guideline stated that they put it into practice. Another 15.3% intended to implement the guideline in the near future, while 42.9% needed more information. Only small numbers of participants were not interested in the guideline or rejected it (4.1% in each category). Fifty-six percent of the physicians stated that introduction of the guideline had altered their diagnosis and treatment of patients with depression, in 57.7% of cases positively (42.3% mixed, 0% negative).

Sample of patients and reference date survey

Three to 5 weeks after the preliminary study, a survey was carried out on a particular day at each physician’s office (71% of these reference dates were in April 2014, the rest earlier or later due to vacation or high workload). All patients who attended for consultations with the participating physicians (n = 253) on the given day were informed about the study by a previously trained member of the physician’s staff or a study monitor and asked to take part. The exclusion criteria were age <18 years, no personal contact with the physician (e.g., just picking up a prescription), inability to fill in the patient questionnaire for physical or mental reasons (e.g., dementia, acute trauma, severe pain), inability to fill in the patient questionnaire without third-party assistance (e.g., sensory or motor deficits, no glasses), and no written consent to participate in the study.

A total of 7143 patients attended the offices of the participating physicians for consultation, of whom 6370 fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in the study (efigure 1). Of these, 3563 patients agreed to take part after receiving detailed information (response rate 55.9%). Patients who declined to join the study were somewhat more likely to be male (44.7% vs. 39.5% of those who agreed to take part) and = 55 years old (59.7% vs. 49.0%). The participating patients filled in a seven-page form, patient questionnaire part A, while they were waiting to see the doctor. In addition to the patients’ biosocial characteristics, this form documented the reason for consultation, symptoms of depression (using the Depression Screening Questionnaire, DSQ [15]), mental disorders diagnosed by a physician, characteristics of disease and treatment including barriers, indirect costs such as loss of productivity through work disability, direct treatment costs, quality of life, and selected guideline-relevant details (availability of materials, joint decision making). The four-page patient questionnaire part B, which could be filled in following the consultation with the physician, documented further mental symptoms, stigma due to depression, functional impairments, and aspects of the doctor–patient relationship. The completed forms were handed to a member of the physician’s staff or a study monitor (not to the physician).

In the patient sample, there were more women (60.4%) than men and 49% of all patients were = 55 years old (mean 53.7, range 18 to 95). 58.1% of the patients were married or in a stable partnership; 48.4% were employed and 31.4% retired. The patients had been registered with their current primary care physician for an average of 10.1 years (SD = 9.4, median 8) and had attended for consultation an average of 3 times in the previous 3 months (SD = 3.1, median 2). On the reference date, most of the patients (61.4%) visited the doctor’s office because of physical symptoms and/or pain. Mental problems were less often stated among the primary reasons for consultation (10.5%); the most frequently mentioned reason was despondency/despair/depression (6.4%), followed by anxiety (3.5%) and other mental problems (4.3%). Sleep problems were reported as reason for consultation by 8.6% of the patients, and 31.8% consulted the primary care physician due to “other” reasons. The majority of patients assessed their general physical and mental health as at least good; 25.9% rated their physical health as poor or very poor, and 19.6% stated poor or very poor mental health.

After each consultation the physician completed a one-page physician questionnaire regarding the patient’s general physical and mental health, together with the diagnoses of any physical (current) and mental disorders (current and previous). The physicians judged the presence of depression on the following criteria:

The presence of other mental disorders (bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, psychosomatic/somatoform disorders, substance use disorders [alcohol, drugs], psychosis, others) was assessed in the same way. If the physician specified a mental disorder (current or previous; definite, subthreshold, or questionable), he/she was asked to detail what was done on the reference date (etable 1). For patients with current or previous depression, the form went on to a second page on which the physician documented the severity of depression, previous history and treatments, supportive/inhibitory factors in treatment, and any other guideline-relevant aspects (e.g., use of aids, joint decision making, and self-assessed implementation of the S3 guideline). The physicians received a payment of € 2.50 for each completed physician questionnaire.

Altogether, 3499 patient questionnaires (3431 of them with data suitable for analysis) and 3402 physician questionnaires (3294 with evaluable data) were completed on the reference date and sent to the study center. Both physician and patient questionnaire were available for 3367 patients. Of these data sets, 3211 could be used and form the basis of the analyses presented here.

Definite depression: all criteria fulfilled

Subthreshold depression: patient clearly depressed but not all criteria fulfilled

Questionable depression: patient could be depressed, but could also have another syndrome

Depression clearly absent

Acknowledgments

Funding and acknowledgements

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

The VERA project was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, BMG) and conducted at the Institute of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy of TU Dresden and at the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Longitudinal Studies (CELOS) leadership of Prof. Dr. Katja Beesdo-Baum and under the co-leadership of Prof. Franziska Einsle and PD Dr. Susanne Knappe. Partners in the project were the German Depression Relief Foundation (Stiftung Deutsche Depressionshilfe), the German Alliance Against Depression (Deutsches Bündnis gegen Depression e. V.; PD Dr. Christine Rummel-Kluge and Ines Heinz, Leipzig), and the Center for Evidence-Based Health Care at the Medical Faculty of TU Dresden (ZEGV; Prof. Dr. Jochen Schmitt). Scientific assistants in the VERA study were Gesine Wieder, Lisa Knothe, Denise Küster, Janine Quittschalle, Diana Pietzner, Abdelilah El Hadad, and Sebastian Trautmann. The fieldwork was supported by regional alliances against depression (Leipzig region: Nicole Koburger, Bettina Haase; Berlin region: PD Dr. Meryam Schouler-Ocak, Theresa Wilbertz; Munich region: Rita Wüst, Dr. Joachim Hein; Fulda region: Dr. Ulrich Walter; Hamburg region: Dr. Hans-Peter Unger) and by a large number of students. Associate partners and advisors of the VERA team were: Prof. Antje Bergmann, Department of General Medicine, TU Dresden; Prof. Ulrich Hegerl, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Leipzig University; Prof. Hans-Ulrich Wittchen and Dr. Michael Höfler, Institute for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, TU Dresden; Dr. Lars Pieper, Torsten Tille, and Henning Schmidt, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Longitudinal Studies (CELOS), TU Dresden; Prof. Jürgen Hoyer, Behavioral Psychotherapy and Outpatient Psychotherapy Clinic, TU Dresden; Prof. Andrea Pfennig, Psychiatric Epidemiology and Outcome Research, TU Dresden; Dipl.-Psych. Christian Klesse, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Freiburg University Hospital, member of the S3 guideline group. The study was supported by the Saxony Association of General Medicine (Sächsische Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin, SGAM; Dr. Johannes Dietrich and Dr. Andreas Schuster) and by AOK Plus (Dr. Ulf Maywald and Andreas Fuchs).

We thank all participating physicians, medical assistants, and patients for their commitment to the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement Prof. Hoyer has received reimbursement of congress attendance fees from AstraZeneca.

PD Dr. Rummel-Kluge has received speaker’s fees from Servier and Jansen.

Prof. Hegerl has been member of the Advisory Boards of Lundbeck and Servier, consultant for Bayer Pharma and speaker for Roche Pharma within the past 3 years.

PD Dr. Schouler-Ocaker has received speaker’s fees and reimbursement of travel costs and congress attendance fees from Forum für medizinische Fortbildung GmbH and Lundbeck GmbH.

Dr. Unger has received speaker’s fees from Otsuka and support for training courses in his department from Servier and Jansen.

Dr. Walter has received reimbursement of travel costs and congress attendance fees from Servier and Merz and speaker’s fees from Lundbeck.

Dr. Hein owns shares in Eli Lilly.

Prof. Pfennig has received assistance with travel costs and congress attendance fees from Otsuka and speaker’s fees from Otsuka and Lundbeck.

Prof. Schmitt has received institutional financial support for research projects from Sanofi, Novartis, ALK, Pfizer, and MSD.

Prof. Bergman receives royalties or author’s fees from Thieme Verlag for the chapter “Angststörungen, Psychotherapie” in the textbook “Duale Reihe Allgemein- und Familienmedizin”.

Prof. Wittchen is faculty member of the Lundbeck Foundation and member of the ThINC-it Steering Board, Lundbeck.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Further authors

Institute of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, TU Dresden: PD Dr. Knappe, Dr. Einsle, Dipl.-Psych. Knothe, Dipl.-Psych. Wieder, M.Sc.-Math. Venz, Prof. Hoyer, Prof. Wittchen

Behavioral Epidemiology, TU Dresden: Dipl.-Psych. Knothe, Dipl.-Psych. Wieder, M.Sc.-Math. Venz

Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Longitudinal Studies, TU Dresden: M.Sc.-Math. Venz, Prof. Wittchen

German Depression Relief Foundation, Leipzig: PD Dr. Rummel-Kluge, Prof. Hegerl

German Alliance Against Depression, Leipzig: Dipl.-Psych. Heinz, Prof. Hegerl

Leipzig Alliance Against Depression, Leipzig: Dipl.-Psych. Koburger

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Leipzig University Hospital, Leipzig: PD Dr. Rummel-Kluge, Dipl.-Psych. Koburger, Prof. Hegerl

University Department of Psychiatry–Charité, St. Hedwig Hospital, Berlin: PD Dr. Schouler-Ocak, Dr. Wilbertz

Harburg Alliance Against Depression, Asklepios Hospital Harburg: Dr. Unger

Academy for Suicide Prevention, Health Network East Hesse, Fulda: Dr. Walter

Munich Alliance Against Depression, Munich: Dr. Hein

Clinical Psychology and Epidemiology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Basel: Prof. Lieb

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, TU Dresden: Prof. Pfennig

Center for Evidence-Based Health Care (ZEGV), Faculty of Medicine, TU Dresden: Prof. Schmitt

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, LMU Munich: Prof. Wittchen

General Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, TU Dresden: Prof. Bergmann

References

- 1.Jacobi F, Hofler M, Siegert J, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: the Mental Health Module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1-MH) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23:304–319. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:718–779. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF (eds.) für die Leitliniengruppe Unipolare Depression. DGPPN, ÄZQ, AWMF. 1. Berlin, Düsseldorf: 2009. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression-Kurzfassung, [Google Scholar]

- 5.DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF (eds.) für die Leitliniengruppe Unipolare Depression. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression - Langfassung. www.depression.versorgungsleitlinien.de (last accessed on 21 August 2017) (2) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Härter M, Klesse C, Bermejo I, Schneider F, Berger M. Clinical practice guideline: unipolar depression—diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations from the current S3/National Health Policy Guideline. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:700–708. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melchior H, Schulz H, Härter M, Walker J, Ganninger M. Faktencheck Gesundheit: Regionale Unterschiede in der Diagnostik und Behandlung von Depressionen. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ormel H, Koeter MWJ, van den Brink W, van de Willige G. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700–706. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilchrist G, Gunn J. Observational studies of depression in primary care: what do we know? BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaebel W, Kowitz S, Fritze J, Zielasek J. Use of health care services by people with mental illness—secondary data from three statutory health insurers and the German statutory pension insurance scheme. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:799–808. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mack S, Jacobi F, Gerschler A, et al. Self-reported utilization of mental health services in the adult German population—evidence for unmet needs? Results of the DEGS1-MentalHealthModule (DEGS1-MH) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23:289–303. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittchen H-U, Winter S, Höfler M, et al. Hausärztliche Interventionen und Verschreibungsverhalten bei Depressionen Ergebnisse der „Depression-2000“-Studie. Fortschr Med. 2000;118:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittchen H-U. Depression 2000. Eine bundesweite Depressions-Screening-Studie in Allgemeinarztpraxen. MMW Fortschr Med. 2000;118:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittchen H-U, Pittrow D. Prevalence, recognition and management of depression in primary care in Germany: the Depression 2000 study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:1–11. doi: 10.1002/hup.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wittchen H-U, Perkonigg A. DIA-X-Screening Verfahren: Fragebogen DIA-SSQ: Screening für psychische Störungen; Fragebogen DIA-ASQ: Screening für Angststörungen; Fragebogen DIA-DSQ: Screening für Depressionen. Frankfurt: Swets & Zeitlinger bv. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO. Switzerland: World Health Organization. Geneva: 1993. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wittchen H-U, Winter S, Höfler M, et al. Häufigkeit und Erkennensrate von Depression in der hausärztlichen Praxis. Fortschr Med. 2000;118:22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider A, Wartner E, Schumann I, Horlein E, Henningsen P, Linde K. The impact of psychosomatic co-morbidity on discordance with respect to reasons for encounter in general practice. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:82–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehm J, Allamani A, Elekes Z, et al. Alcohol dependence and treatment utilization in Europe—a representative cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16 doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trautmann S, Pieper L, Kuitunen-Paul S, et al. Prävalenz und Behandlungsraten von Störungen durch Alkoholkonsum in der primärärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschland. SUCHT. 2016;62:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boenisch S, Kocalevent R-D, Matschinger H, et al. Who receives depression-specific treatment? A secondary data-based analysis of outpatient care received by over 780,000 statutory health-insured individuals diagnosed with depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:475–486. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0355-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiegand HF, Sievers C, Schillinger M, Godemann F. Major depression treatment in Germany-descriptive analysis of health insurance fund routine data and assessment of guideline-adherence. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.IGES - Institut für Gesundheits- und Sozialforschung. IGES Institut GmbH. Berlin: 2012. Bewertung der Kodierqualität von vertragsärztlichen Diagnosen - Eine Studie im Auftrag des GKV-Spitzenverbands in Kooperation mit der BARMER GEK. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostisches und Statistisches Manual Psychischer Störungen - DSM-5: Deutsche Ausgabe herausgegeben von Falkai P, Wittchen H-U, mitherausgegeben von Döpfner M, Gaebel W, Maier W, Rief W, Saß H, Zaudig M. Göttingen: Hogrefe. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374:609–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60879-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobi F, Höfler M, Meister W, Wittchen H-U. Prävalenz, Erkennens- und Verschreibungsverhalten bei depressiven Syndromen. Nervenarzt. 2002;73:651–658. doi: 10.1007/s00115-002-1299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mergl R, Seidscheck I, Allgaier AK, Moller HJ, Hegerl U, Henkel V. Depressive, anxiety, and somatoform disorders in primary care: prevalence and recognition. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:185–195. doi: 10.1002/da.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell AJ, Rao S, Vaze A. International comparison of clinicians‘ ability to identify depression in primary care: meta-analysis and meta-regression of predictors. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e72–e80. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X556227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sielk M, Altiner A, Janssen B, Becker N, de Pilars MP, Abholz HH. Prevalence and diagnosis of depression in primary care a critical comparison between PHQ-9 and GPs‘ judgement. Psychiatr Prax. 2009;36:169–174. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1090150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen KS, Sokolowski I, Olesen F. Case-finding and risk-group screening for depression in primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011;29:80–84. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2011.554009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Güthlin C, Beyer M, Erler A, et al. Rekrutierung von Hausarztpraxen für Forschungsprojekte Erfahrungen aus fünf allgemeinmedizinischen Studien. Z Allgemeinmed. 2012;88:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumeyer-Gromen A, Lampert T, Stark K, Kallischnigg G. Disease management programs for depression—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Care. 2004;42:1211–1221. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harter M, Bermejo I, Ollenschlager G, et al. Improving quality of care for depression: the German action programme for the implementation of evidence-based guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18:113–119. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wittchen H-U, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H. Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:568–578. doi: 10.1007/s001270050095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: 1990. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittchen H-U, Pfister H. Swets & Zeitlinger. Frankfurt: 1997. DIA-X-Interviews: Manual für Screening-Verfahren und Interview; Interviewheft Längsschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-Lifetime); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X-Lifetime); Interviewheft Querschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-12 Monate); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X-12Monate); PC-Programm zur Durchführung des Interviews (Längs- und Querschnittuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD The PHQ Primary Care Study. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS

Supplementary informationen about the VERA study

The nationwide multistage epidemiological study program on the treatment of depression in primary care settings in Germany (the VERA study) comprises a preliminary study, a main study with a cross-sectional (reference date) and a longitudinal component (follow-up surveys after 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months), two embedded add-on studies (a cluster-randomized intervention study and a diagnostic validation study), and a health-economics evaluation component. The study protocol was reviewed by the ethics board of TU Dresden (EK-392102013). The present article refers to the cross-sectional reference date survey, together with data from the preliminary study.

Sample of physicians and preliminary study

On the basis of a regionally clustered random selection of physicians engaged in primary care from the physicians’ directory, in late 2013 and early 2014 we sent letters to doctors in six regions of Germany (Berlin, Dresden, Fulda/Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Munich), stratified by location (city, town, rural). In these letters, the physicians were informed about the aim of the study and how it would be carried out and asked to participate. Recruitment of physicians was supported by personal visits and telephone calls from regional study coordinators/monitors (members of the Regional Alliances Against Depression and students/ scientific assistants involved in the study). The target was recruitment of 300 physicians.

Altogether, letters were sent to 4990 physicians, 391 of whom were registered as quality-neutral dropouts (e.g., retirement, sickness/death, moved away) (efigure 1). Of the remaining 4599 physicians, 269 gave their written agreement to take part in the study (response rate 5.8%). Two hundred sixty of these provided sufficient information in a preliminary questionnaire with details about themselves and the nature of their offices, their attitudes towards depression and its treatment, and their opinions on the acceptance and implementation of the S3 guideline. Each physician who completed the six-page questionnaire received € 10.

The mean age of the physicians who took part in the study was 52.0 years (standard deviation [SD] 8.8, range 26–79, 36.6% <50 years), and 53.9% were female. Similarly to the age and gender structure of the primary care physicians registered in medical associations across Germany in 2014 (according to the Federal Health Report), the VERA sample of physicians is characterized by a comparably high proportion of women (VERA: 53.9 female; nationwide: 43.4% female) and a high number of young doctors (VERA: 36.6% <50 years; nationwide: 29.4% <50 years). Almost one quarter (23.5%) of the physicians stated that they had worked in a psychiatric facility. Overall, the participants had been working as primary care physicians in Germany for an average of 15.1 years (SD 9.4, range 0–45 years). A small proportion of them possessed an additional qualification in psychotherapy (5.5%) or were training in psychotherapy (2.4%); the majority had an additional qualification in basic psychosomatic care (74%, with a further 2.4% in training).

The physicians reported seeing a mean of 39.2 patients/day (median 40, range 5 to 90) and spending 11 min on each patient (SD 3.9, median 10). The participants’ estimation of their competence in detection and diagnosis of depression was predominantly positive (good 68.6%, moderate 31.4%, poor 0%), but they rated their competence in drug treatment somewhat less highly (good 36.4%, moderate 53.9%, poor 9.7%). Competence in psychotherapy was stated as good by 23.6% of the physicians, as moderate by 43.2%, and as poor by 33.2%.

Most of the physicians who took part in the study considerd guidelines to be generally helpful in their daily work (full agreement 33.1%, partial agreement 49.8%; disagreement 17.1%). The 41% of the physicians who stated they knew the S3 guideline on unipolar depression estimated their familiarity with it on a scale ranging between 0 and 100%; the average figure was 54.4% (SD = 24.7). Knowledge of the S3 guideline was independent of the physicians’ age or their possession of an additional qualification in basic psychosomatic care, but tended to be greater among those with an additional qualification in psychotherapy (55.6% for physicians with the qualification or training for it vs. 40.0% for those without the qualification) and in those who had attended at least one course related to depression in the previous 2 years (43.7% vs. 33.3% for physicians who had not attended such a course in the same period). One third (33.7%) of the physicians with self-reported knowledge of the guideline stated that they put it into practice. Another 15.3% intended to implement the guideline in the near future, while 42.9% needed more information. Only small numbers of participants were not interested in the guideline or rejected it (4.1% in each category). Fifty-six percent of the physicians stated that introduction of the guideline had altered their diagnosis and treatment of patients with depression, in 57.7% of cases positively (42.3% mixed, 0% negative).

Sample of patients and reference date survey

Three to 5 weeks after the preliminary study, a survey was carried out on a particular day at each physician’s office (71% of these reference dates were in April 2014, the rest earlier or later due to vacation or high workload). All patients who attended for consultations with the participating physicians (n = 253) on the given day were informed about the study by a previously trained member of the physician’s staff or a study monitor and asked to take part. The exclusion criteria were age <18 years, no personal contact with the physician (e.g., just picking up a prescription), inability to fill in the patient questionnaire for physical or mental reasons (e.g., dementia, acute trauma, severe pain), inability to fill in the patient questionnaire without third-party assistance (e.g., sensory or motor deficits, no glasses), and no written consent to participate in the study.

A total of 7143 patients attended the offices of the participating physicians for consultation, of whom 6370 fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in the study (efigure 1). Of these, 3563 patients agreed to take part after receiving detailed information (response rate 55.9%). Patients who declined to join the study were somewhat more likely to be male (44.7% vs. 39.5% of those who agreed to take part) and = 55 years old (59.7% vs. 49.0%). The participating patients filled in a seven-page form, patient questionnaire part A, while they were waiting to see the doctor. In addition to the patients’ biosocial characteristics, this form documented the reason for consultation, symptoms of depression (using the Depression Screening Questionnaire, DSQ [15]), mental disorders diagnosed by a physician, characteristics of disease and treatment including barriers, indirect costs such as loss of productivity through work disability, direct treatment costs, quality of life, and selected guideline-relevant details (availability of materials, joint decision making). The four-page patient questionnaire part B, which could be filled in following the consultation with the physician, documented further mental symptoms, stigma due to depression, functional impairments, and aspects of the doctor–patient relationship. The completed forms were handed to a member of the physician’s staff or a study monitor (not to the physician).

In the patient sample, there were more women (60.4%) than men and 49% of all patients were = 55 years old (mean 53.7, range 18 to 95). 58.1% of the patients were married or in a stable partnership; 48.4% were employed and 31.4% retired. The patients had been registered with their current primary care physician for an average of 10.1 years (SD = 9.4, median 8) and had attended for consultation an average of 3 times in the previous 3 months (SD = 3.1, median 2). On the reference date, most of the patients (61.4%) visited the doctor’s office because of physical symptoms and/or pain. Mental problems were less often stated among the primary reasons for consultation (10.5%); the most frequently mentioned reason was despondency/despair/depression (6.4%), followed by anxiety (3.5%) and other mental problems (4.3%). Sleep problems were reported as reason for consultation by 8.6% of the patients, and 31.8% consulted the primary care physician due to “other” reasons. The majority of patients assessed their general physical and mental health as at least good; 25.9% rated their physical health as poor or very poor, and 19.6% stated poor or very poor mental health.

After each consultation the physician completed a one-page physician questionnaire regarding the patient’s general physical and mental health, together with the diagnoses of any physical (current) and mental disorders (current and previous). The physicians judged the presence of depression on the following criteria:

The presence of other mental disorders (bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, psychosomatic/somatoform disorders, substance use disorders [alcohol, drugs], psychosis, others) was assessed in the same way. If the physician specified a mental disorder (current or previous; definite, subthreshold, or questionable), he/she was asked to detail what was done on the reference date (etable 1). For patients with current or previous depression, the form went on to a second page on which the physician documented the severity of depression, previous history and treatments, supportive/inhibitory factors in treatment, and any other guideline-relevant aspects (e.g., use of aids, joint decision making, and self-assessed implementation of the S3 guideline). The physicians received a payment of € 2.50 for each completed physician questionnaire.

Altogether, 3499 patient questionnaires (3431 of them with data suitable for analysis) and 3402 physician questionnaires (3294 with evaluable data) were completed on the reference date and sent to the study center. Both physician and patient questionnaire were available for 3367 patients. Of these data sets, 3211 could be used and form the basis of the analyses presented here.

Definite depression: all criteria fulfilled

Subthreshold depression: patient clearly depressed but not all criteria fulfilled

Questionable depression: patient could be depressed, but could also have another syndrome

Depression clearly absent