Abstract

Background

To identify the rate of and risk factors for contralateral inguinal hernia (CIH) after unilateral inguinal hernia repair in adult male patients.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study identified from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Information on all adult patients who underwent primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair without any other operation was collected using ICD-9 diagnostic and procedure codes. The exclusion criteria were laparoscopic hernia repair, non-primary repair, complicated hernia, other combined procedures, female and undetermined gender.

Results

A total of 170,492 adult male patients were included, with a median follow-up of 87 months. The overall CIH rate was 10.5%, with a median time of 48 months to a subsequent hernia operation. The 1-year, 2-year, 3-year and 5-year-recurrent rate was 2.6, 3, 4.3, and 6.7% respectively. Further, 3.7% patients who underwent CIH repair had a complicated inguinal hernia. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that age > 45 y, direct hernia, cirrhosis (HR = 1.564), severe liver disease (HR = 1.663), prostate disease (HR = 1.178), congestive heart failure (HR = 1.138), and history of malignancy (HR = 1.116) had a significantly higher risk of CIH repair.

Conclusions

Among adult male patients undergoing long-term follow-up, we identified several significant risk factors for CIH repair. If these risk factors are presented, the surgeon should inform the following risk of CIH repair to patients so that it can be repaired as soon as possible.

Keywords: Contralateral inguinal hernia repair, Contralateral exploration, Herniorrhaphy, National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD)

Background

After unilateral inguinal hernia repair, some patients experience a contralateral inguinal hernia (CIH) and require subsequent surgical repair. Previous reports have shown that ≤30% patients develop CIH [1]. In the era of conventional hernia repair, few studies have researched the risk factors of CIH repair. Although we have identified high-risk patients, it is still difficult to determine which patients should undergo exploration of the contralateral side during the initial surgery because it may make a subsequent procedure more difficult [2, 3]. Therefore, following traditional hernia repair, surgeons typically advise patients to observe the contralateral side closely for the development of a new hernia so that a surgeon can repair it.

Unfortunately, to date, reports on adults have seldom discussed the risk factors for CIH repair. Unlike infants and children, the risk factors associated with and results of CIH repair have been widely discussed [4, 5]. Only one study used a non-Medicare claims database to analyze the risk factors for treatment of CIH and showed that an older age and prostate disease were risk factors [6].

The goal of this study was to identify the risk factors for CIH repairs in male adults based on data in the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan, which covers 97% of the country’s medical providers and about 99% of its citizens. Surgeons can use these data to identify high-risk patients to inform high-risk patients that they should pay attention to the possibility of a CIH so that it can be repaired as soon as possible.

Methods

Study sample and identification of hernia repair surgery

This study is based in part on data from NHIRD, provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare and managed by the National Health Research Institutes (registered number NHIRD-103-246). For our analysis, we extracted information on all adult patients with discharge diagnoses that included ICD-9 codes for a hernia (ICD codes 550.xx to 553.xx) combined with surgical procedure codes for unilateral inguinal hernia repair (53.00 to 53.05) [7, 8] from inpatient expenditures by admissions in NHIRD from 1996 to 2013.

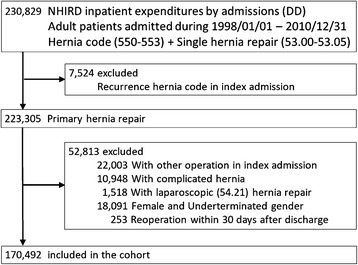

Patients who underwent other operations during the same admission were excluded. Moreover, patients with a recurrent hernia (ICD coding: 550.01, 550.03, 550.11, 550.13, 550.91, and 550.93) [8], a complicated hernia (ICD-9 codes including 550.0x, 550.1x, 551.x, and 552.x [9]), women or undetermined gender were excluded. Patients discharged after undergoing laparoscopic surgery (ICD code 54.21) that indicates patients may receive laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, were excluded. Patients who underwent reoperation within 30 days of the initial unilateral inguinal hernia repair were also excluded [10]. All patients admitted between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2010 who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were enrolled into the analysis. All included patients were followed until their death or the end of the study period, December 31, 2013. Death was defined as withdrawal of patients from the NHI program [11]. The selection algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Definition of CIH repair

The primary endpoint was CIH repair. CIH repair was defined as reoperation after more than 30 days following the initial hernia repair [10] and any of the following: 1) patients undergoing a second unilateral hernia repair, and 2) patients who underwent bilateral inguinal hernia repair after the initial unilateral inguinal hernia repair.

Characteristics and comorbidity of patients

The patients were separated into groups based on age as follows: 18–45 years, 45–65 years, 65–80 years, and >80 years. Type of hernia (53.01, 53.03 for direct type, 53.02, 53.04 for indirect type; and 53.00, 53.05 for unspecified, respectively) and whether mesh placement occurred (53.03, 53.04 and 53.05 for repair with mesh; 53.00, 53.01, and 53.02 for repair without mesh) were also identified by ICD-9 code. During analysis, we assessed 18 independent variables as comorbidities (Appendix), including 15 different medical categories based on the Charlson comorbidity index [12]: prostate disease (ICD-9-CM code 600.x, 601.x, 602.x), which was reported as a risk factor for CIH repair [6]; obesity (ICD-9-CM code: 278.00, 278.01 [13]); and hypertension (ICD-9-CM code: 401.x-405.x [11]). Comorbidities identified by an ICD code within the NHIRD database before admission were included as comorbidities.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) for the descriptive statistics and contingency tables for data analysis. Differences in CIH repair rates among age groups, gender, and comorbidities are listed in the contingency table and were compared using a chi-square test. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to identify the percentage of patients who did not have a CIH repair in the following period. The risk of CIH repair among different covariates was evaluated using a backward stepwise Cox proportional hazards model. Variables with P values less than 0.2 were inserted into a Cox regression for a multivariant analysis [14]. Death before CIH repair was thought to be a competing factor and was also inserted into the Cox model for analysis. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with the Helsinki Declaration and was fully evaluated and proved by the Institutional Review Board of Buddhist Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital approved this study (B10304006-1).

Results

We identified 230,829 patients who underwent unilateral hernia repair between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2010. Further, 7524 patients who underwent a repair for a recurrent hernia were excluded. We also excluded 22,003 patients who underwent other operations during the same admission: 10,948 patients underwent an operation for a complicated inguinal hernia; 1518 patients underwent a laparoscopic procedure, and 16,841 female patients and 1503 patients were of undeterminated gender. Finally, 170,942 patients were included in the study cohort. The patient selection algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 1.

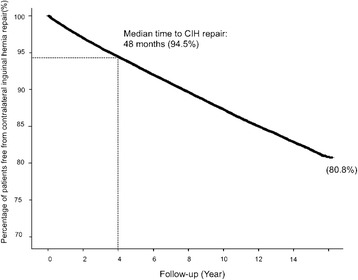

Estimation of the CIH repair rate after unilateral inguinal hernia repair

This group had a median follow-up time of 87 months. The overall CIH repair rate was 10.5% (17,879 patients). The cumulative incidence of CIH repair, which was demonstrated by Kaplan–Meier analysis, gradually increased without abrupt fluctuations (Fig. 2). At the end of the cohort, 80.8% of the included patients did not undergo a CIH repair with a median time of 48 months from the first surgery to subsequent CIH repair. The 1-year, 2-year, 3-year and 5-year-recurrent rate was 2.6, 3, 4.3, and 6.7% respectively. There were 3.7% patients (654/17,879 patients) who underwent CIH repair for a complicated inguinal hernia.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of contralateral inguinal hernia rates after primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair in male adult patients

CIH repair rate in different clinical characteristics and comorbidities

Table 1 demonstrates the CIH repair rate in different clinical characteristics. Patients between 18 and 45 years of age had the lowest rate of subsequent CIH repair than patients in any other age group. The rate gradually increased with age and decreased in patients aged >80 years. Regarding inguinal hernia type, a direct hernia was associated with a significantly higher rate of CIH repair than an indirect hernia (direct vs. indirect = 11.8% vs. 9.4%, respectively; P < 0.001). Further, patients whose primary inguinal hernia was repaired without mesh had a significantly higher proportion of CIH repairs than those who were repaired with mesh (without mesh vs. with mesh = 11.4% vs. 8.0%, respectively; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Contralateral inguinal hernia (CIH) repair rate according to different clinical characteristics in 170,492 male adult patients after primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair (Overall: 10.5%; second operation: 3.7% complicated)

| Clinical Characteristics | Total patients | CIH repair events | CIH Rate | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | <0.001 | |||

| 18–45 | 43,075 | 02,541 | 05.9% | |

| 45–65 | 59,866 | 07,130 | 11.9% | |

| 65–80 | 54,503 | 07,134 | 13.1% | |

| > 80 | 13,048 | 01,074 | 08.2% | |

| Type of hernia | <0.001 | |||

| Indirect | 92,139 | 08,685 | 09.4% | |

| Direct | 46,347 | 05,447 | 11.8% | |

| Unspecific | 32,006 | 03,747 | 11.7% | |

| Mesh or not | <0.001 | |||

| Without mesh | 125,826 | 14,297 | 11.4% | |

| With mesh | 044,666 | 03,582 | 08.0% |

Risk factors for CIH in male patients

Several comorbidities showed a significant difference in subsequent CIH repair rates (Table 2), including congestive heart failure (P = 0.032), peripheral vascular disease (P = 0.023), cerebrovascular disease (P = 0.014), dementia (P = 0.001), diabetes mellitus (P < 0.001), renal disease (P < 0.001), and prostate disease (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Contralateral inguinal hernia (CIH) repair rates in different comorbidity groups in 170,492 male adult patients after primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair

| Comorbidities | CIH rate | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 10.5% | 10.1% | =0.556 |

| Congestive heart failure | 10.5% | 9.5% | =0.032* |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 10.5% | 8.2% | =0.023* |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 10.5% | 9.7% | =0.014* |

| Dementia | 10.5% | 6.5% | <0.001* |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 10.5% | 10.5% | =0.912 |

| Rheumatic disease | 10.5% | 07.8% | =0.106 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 10.5% | 10.7% | <0.521 |

| Mild liver disease | 10.5% | 09.8% | 0.074 |

| Cirrhosis | 10.5% | 11.2% | =0.134 |

| Severe liver disease | 10.5% | 11.9% | =0.055 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10.6% | 8.8% | <0.001* |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 10.5% | 8.8% | =0.123 |

| Renal disease | 10.5% | 8.1% | <0.001* |

| History of malignancy | 10.5% | 9.8% | =0.055 |

| Obesity | 10.5% | 4.5% | =0.319 |

| Hypertension | 10.5% | 10.2% | 0.051 |

| Prostate disease | 10.2% | 12.1% | <0.001* |

*p < 0.05

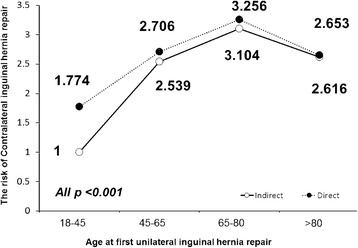

After a multivariant analysis using a Cox regression model, patients who were aged >45 years had a significantly higher risk of CIH than younger men (45-65 years: HR 2.241, 95% CI 2.140-2.347; 65-80 years: HR 2.723, 95% CI 2.594-2.859; >80 years: HR 2.306, 95% CI 2.135-2.491; all P < 0.001). Also, patients with a direct hernia had a higher risk of CIH repair than patients with an indirect hernia (HR 1.113, 95% CI 1.075-1.152; P < 0.001). Figure 3 demonstrates differences in risk among inguinal hernia types in each age group. Compared with patients aged 18–45 years with an indirect hernia, older patients had a higher CIH repair risk. Further, patients with a direct hernia had a significantly higher risk in all age groups (all P value <0.001).

Fig. 3.

Hazard Ratio (HR) associated with Contralateral inguinal hernia (CIH) repair among inguinal hernia types in each age group

Other factors are summarized in Table 3. Patients who underwent mesh repair for a primary unilateral inguinal hernia had a significantly lower risk of subsequent CIH repair (HR 0.887, 95% CI 0.854-0.921, P < 0.001). As for comorbidities, congestive heart failure (HR 1.138, P = 0.011), cirrhosis (HR 1.564, P < 0.001), severe liver disease (HR 1.663, P < 0.001), history of malignancy (HR 1.116, P = 0.004), and prostate disease (HR 1.178, P < 0.001) were identified as risk factors for CIH repair. Patients with diabetes had a relatively lower risk than patients without diabetes (HR 0.874, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Risk factors associated with contralateral inguinal hernia (CIH) repair rate in 170,492 male adult patients after primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair as shown by Cox regression analysis

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characters of index operation | |||

| Age, y | |||

| 18–45 | 1 | ||

| 45–65 | 2.241 | (2.140 – 2.347) | <0.001* |

| 65–80 | 2.723 | (2.594 – 2.859) | <0.001* |

| > 80 | 2.306 | (2.135 – 2.491) | <0.001* |

| Hernia type | |||

| Indirect type | 1 | ||

| Direct type | 1.113 | (1.075 – 1.152) | <0.001* |

| Mesh placement | |||

| Without mesh | 1 | ||

| With mesh | 0.887 | (0.854–0.921) | <0.001* |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Severe liver disease | 1.663 | (1.398–1.979) | <0.001* |

| Cirrhosis | 1.564 | (1.382–1.771) | <0.001* |

| Prostate disease | 1.178 | (1.129–1.230) | <0.001* |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.138 | (1.030–1.256) | =0.011* |

| History of malignancy | 1.116 | (1.035–1.203) | =0.004* |

| Diabetes | 0.874 | (0.820–0.932) | <0.001* |

| Renal disease | 0.900 | (0.793–1.022) | <=0.105 |

| Dementia | 0.840 | (0.639–1.104) | <=0.221 |

| Rheumatic disease | 0.799 | (0.551–1.158) | <=0.236 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 1.137 | (0.898–1.441) | <=0.286 |

| Vascular disease | 0.891 | (0.711–1.116) | <=0.314 |

| Hypertension | 1.015 | (0.973–1.059) | <=0.485 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.013 | (0.941–1.090) | <=0.737 |

| Mild liver disease | 0.997 | (0.917–1.085) | <=0.948 |

*Significant

Discussion

In this study, we identified several results. First, as patients aged, the rate of CIH repair also increased. Second, several risk factors associated with CIH repair in male patients were identified, including severe liver disease (including esophageal varices bleeding, hepatic coma, portal hypertension, and other sequelae of chronic liver disease), history of cirrhosis, prostate disease, congestive heart failure, and history of malignancy. However, mesh placement and diabetes were identified as protective factors during CIH repair in male patients.

During the study, we used a Cox regression model for a multivariant analysis instead of a binary variable because we believed that the time to CIH repair was an important factor for patients. As for age as a risk factor, we demonstrated that the rate of CIH repair increases with age in male patients, which may be related to increasing muscular weakness with age. However, the risk declined in patients >80 years. In our study, we identified 59.9% patients older than 80 years who died before their CIH repair. This rate was significantly higher than in other groups (65-80 years: 37.3%; 45-65 years: 11.7%; <45 years: 5.4%; P < 0.001). The higher proportion of the competing event, die before CIH repair, could explain the drop in ratio and risk of CIH repair in age >80 y/o groups.

We excluded patients who may undergo a laparoscopic hernia repair (LIHR). Although there was no strong evidence to prove that LIHR significantly decreased the CIH rate, as compared with a traditional hernia repair, the reported CIH rate after LIHR of about 1–5% was lower than that after traditional inguinal hernia repair of 8–22% [15–19]. Moreover, as we previously mentioned, contralateral exploration during LIHR has been reported to be an easy and safe procedure. Some previously asymptomatic, unrecognized synchronous hernias may have been repaired during laparoscopy and thus could have been recorded as a bilateral inguinal hernia repair in the NHI database, which may influence the overall rate and make the risk factors we identified have more confounders. Therefore, we excluded this issue from our study cohort.

Previously, in the era when tension-free hernia repair was not popular, sequential bilateral inguinal hernia repair may have been performed with a 1-week interval with general anesthesia or at least a 48-h interval with local anesthesia for recovery and mobilization [20, 21]. Moreover, in our clinical experience, some surgeons would repair bilateral hernias separately because of patient comorbidities. Under the NHI system of Taiwan, patients who are readmitted within 14 days would be considered as having incomplete treatment or complications from a previous admission; thus, the payment would be less. If surgeons choose to repair bilateral inguinal hernias, patients would be admitted >14 days after a previous discharge date. Moreover, Saleh et al. indicated that reoperation within 30 days was thought to be an unreliable variable because a particular reoperation may not be related to the initial surgery [10]. Thus, we excluded patients who underwent reoperation within 30 days.

Based on our results, the direct hernia is a risk factor for CIH repair in men. It may indicate greater abdominal wall weakness if patients develop a direct hernia and explain why patients with a direct hernia have a higher risk of CIH. As for prostate disease, severe liver disease, and cirrhosis, we thought these conditions had a higher risk because of increased abdominal pressure and chronic straining [6]. Previously, one Korean journal indicated that the incidence of long-term recurrence and contralateral metachronous hernia repair after unilateral inguinal hernia repair in liver cirrhosis patients does not differ from that of patients without cirrhosis [22]. However, this previously mentioned study involved fewer cases (129 patients with liver cirrhosis) than our study. We believe that our result provides a more accurate prediction of the risk of CIH repair.

In recent years, mesh placement during hernia repair was thought to be the gold standard for inguinal hernia repair. A recurrence rate of 0.2%–25% was demonstrated, and recurrence decreased by about 50%–75% after inguinal hernia repair, as compared with conventional non-mesh methods [23]. Even after 10 years of follow-up, mesh repair is still superior to non-mesh repair because of significantly lower recurrence risks (1% vs. 17%, respectively; P = 0.005) [24]. Further, no data in literature have demonstrated that mesh repair would increase or decrease the risk of CIH repair. Our result showed mesh repair could lower the risk of CIH repair. It might be related to the foreign body sensation after mesh repair. It was reported that 20% patients might have foreign body sensation, 3.7% hyperthesia and 19% hypothesia of the inguinal area after mesh repair [25]. This may remind the patient continuously and influenced patients’ daily activity, reduce the chance of lifting heavy materials and cause the decrease of contralateral inguinal hernia repair.

As for other comorbidities including a history of malignancy and congestive heart failure served as risk factors, and diabetes served as a protective factor, to our knowledge, no previous journal articles mentioned these factors. For the history of malignancy and congestive heart failure, chronic illness and relatively poor nutrition status may play a role in the development of CIH. In the other hand, patients with diabetes are often taught to take care of their limbs to prevent unhealed wound. This may retrain their activity amount or intensity. Probably, the risk of contralateral inguinal hernia decreased. However, the definitive mechanism is still unclear. These identified factors may provide surgeons a guideline to perform contralateral exploration during laparoscopic hernia repair for unilateral inguinal hernia or to inform high-risk patients the possibility of developing a contralateral inguinal hernia. However, mechanisms regarding the protective effect of mesh and diabetes treatment in contralateral inguinal hernia repair are still unclear. Further study is necessitated to clarify the mechanism.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, for our analysis, we used only inpatient expenditures by admissions. There were no records on repairs performed in outpatient departments, repairs in other countries, or self-paid repair during the follow-up period. Some patients who underwent an operation in the outpatient department would not be included in the cohort. However, we believed that considering patients who were admitted for hernia repair would accurately reflect the rate of significant CIH. Consequently, we believed that this rate could help surgeons identify patients who would need contralateral exploration during laparoscopic unilateral inguinal hernia repair or surgeons advise those high-risk patients who should pay attention to symptoms of CIH after traditional inguinal hernia repair.

Second, we could not delve into the details of each physician’s notes to determine the type of mesh placed, mesh fixation methods, or any other factors such as changes in technique and experience of the surgeon, the severity of cirrhosis, or stage of malignancies that were not recorded in the database or identified by ICD-9. Thus, we could not conduct additional subgroup evaluations on these topics. However, we used NHIRD, which covers 97% of medical providers in Taiwan and about 99% of its citizens and records all medical behaviors in the country. Thus, we could detect contralateral inguinal hernia repair once a patient was admitted in Taiwan. We thought that such a long followed-up period could detect almost all contralateral inguinal hernia repair in Taiwan and offer a comprehensive and reliable data source for the present study.

Third, the risk of miscoding exists. In the NHI database, upon admission, diagnosis and procedures performed were recorded according to ICD-9. However, surgeons in Taiwan have always used a different coding system, Health Insurance Surgical Orders from the Taiwan NHI payment system, which directly relates to the revenue earned by surgeons. However, as it was directly related to hospital income, professional coders provided mostly these records in this database that were based on the entire admission course. Moreover, an official comparison table is offered by the National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare to help increase the preciseness of these different codes. Moreover, we believed that the likelihood of miscoding of the surgical procedures was limited.

Conclusion

For patients with a median follow-up of 87 months, 10.5% of the patients needed to undergo CIH repair with a median of 48 months from the first surgery to subsequent CIH repair. The 1-year, 2-year, 3-year and 5-year-recurrent rate was 2.6, 3, 4.3, and 6.7% respectively. Moreover, 3.7% of these patients experienced a complicated hernia. We identified several significant risk factors for CIH repair following traditional unilateral hernia repair including age >45 years, direct hernia, and comorbidities including cirrhosis, severe liver disease, prostate disease, congestive heart failure, and history of malignancy. Patients who were repaired with mesh had a relatively lower risk. If these risk factors are present, surgeons should inform patients that they should pay attention to the possibility of a CIH, so it can be repaired as soon as possible.

Acknowledgments

Acknowlegements

This study is based in part on data from National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare and managed by the National Health Research Institutes (registered number NHIRD-103-246) and published by Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) Bureau. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

Funding

There is no funding supported this study.

Availability of data and materials

This study is based in part on data from National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). The data utilized in this study cannot be made available in the manuscript, the supplemental files, or in a public repository due to the “Personal Information Protection Act” executed by Taiwan’s government, starting from 2012. Requests for data can be sent as a formal proposal to the NHIRD (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw) or by email to nhird@nhri.org.tw.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIH

Contralateral inguinal hernia

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LIHR

laparoscopic hernia repair

- NHI

Taiwan National Health Insurance

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

Appendix

Table 4.

Translation of comorbidities into ICD-9-CM Codes

| Diagnostic Category | ICD-9-CM Codes | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | 410-410.9 | Acute myocardial infarction |

| 412 | Old myocardial infarction | |

| Congestive heart failure | 428-428.9 | Heart failure |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 443.9 | Peripheral vascular disease, including intermittent claudication |

| 441-441.9 | Aortic aneurysm | |

| 785.4 | Gangrene | |

| V43.4 | Blood vessel replaced by prosthesis | |

| Procedure 38.48 | Resection and replacement of lower limb arteries | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 430-438 | Cerebrovascular disease |

| Dementia | 290-290.9 | Senile and presenile dementias |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 490-496 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| 500-505 | Pneumoconioses | |

| 506.4 | Chronic respiratory conditions due to fumes and vapors | |

| Rheumatologic disease | 710.0 | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| 710.1 | Systemic sclerosis | |

| 710.4 | polymyositis | |

| 714.0-714.2 | Adult rheumatoid arthritis | |

| 714.81 | Rheumatoid lung | |

| 725 | Polymyalgia rheumatica | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 531-534.9 | Gastric, duodenal and gastrojejunal ulcers |

| 531.4-531.7 | Chronic forms of peptic ulcer disease (subset of above listing) | |

| 532.4-532.7 | ||

| 533.4-533.7 | ||

| 534.4-534.7 | ||

| Mild liver disease | 571.4-571.49 | Chronic hepatitis |

| 070.22, 070.23, 070.32, 070.33 | Chronic hepatitis B | |

| 070.44,070.54, | Chronic hepatitis C | |

| 070.6*, 070.9* | Unspecified hepatitis | |

| Cirrhosis | 571.2 | Alcoholic cirrhosis |

| 571.5 | Cirrhosis without mention of alcohol | |

| 571.6 | Biliary cirrhosis | |

| Severe liver disease | 572.2-572.8 | Hepatic coma, portal hypertension, other sequelae of chronic liver disease |

| Diabetes | 250-250.3 | Diabetes with or without acute metabolic disturbances |

| 250.7 | Diabetes with peripheral circulatory disorders | |

| 250.4-250.6 | Diabetes with renal, ophthalmic, or neurological manifestations | |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 344.1 | Paraplegia |

| 342-342.9 | Hemiplegia | |

| Renal disease | 582-582.9 | Chronic glomerulonephritis |

| 583-583.7 | Nephritis and nephropathy | |

| 585 | Chronic renal failure | |

| 586 | Renal failure, unspecified | |

| 588-588.9 | Disorders resulting from impaired renal function | |

| History of malignancy | 140-172.9 | Malignant neoplasms |

| 174-195.8 | Malignant neoplasms | |

| 200-208.9 | Leukemia and lymphoma | |

| 196-199.1 | Secondary malignant neoplasm of lymph nodes and other organs | |

| Hypertension | 401-405.9 | Hypertension |

| Prostate disease | 600-602.9 | Prostate disease |

| Obesity | 278.00, 278.01 | Obesity |

Authors’ contributions

WYY, CHL and JHC designed the study. JCW and JHC are involved with methodology and data analysis. CHL, YTC, CFC and JHC are involved with writing the manuscript. JHC and CHL were responsible for the study conception, design, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with the Helsinki Declaration and was fully evaluated and proved by the Institutional Review Board of Buddhist Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital approved this study (B10304006-1).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cheng-Hung Lee, Email: kawa199190@gmail.com.

Yu-Ting Chiu, Email: amaryllis7035@gmail.com.

Chi-Fu Cheng, Email: drjeffmd@hotmail.com.

Jin-Chia Wu, Email: wccstillthought@yahoo.com.tw.

Wen-Yao Yin, Email: 8931127@gmail.com.

Jian-Han Chen, Email: jamihan1981@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hay JM, Boudet MJ, Fingerhut A, Poucher J, Hennet H, Habib E, Veyrieres M, Flamant Y. Shouldice inguinal hernia repair in the male adult: the gold standard? A multicenter controlled trial in 1578 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222(6):719–727. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199512000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memon MA, Fitzgibbons RJ. The SAGES manual: fundamentals of laparoscopy, Thoracoscopy, and GI endoscopy. 2006. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: Transabdominal Preperitoneal (TAPP) and totally Extraperitoneal (TEP) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wellwood J, Sculpher MJ, Stoker D, Nicholls GJ, Geddes C, Whitehead A, Singh R, Spiegelhalter D. Randomised controlled trial of laparoscopic versus open mesh repair for inguinal hernia: outcome and cost. BMJ. 1998;317(7151):103–110. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7151.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoshino M, Sugito K, Kawashima H, Goto S, Kaneda H, Furuya T, Hosoda T, Masuko T, Ohashi K, Inoue M, et al. Prediction of contralateral inguinal hernias in children: a prospective study of 357 unilateral inguinal hernias. Hernia. 2014;18(3):333–337. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1099-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong H, Wang F. Contralateral metachronous hernia following negative laparoscopic evaluation for contralateral patent processus vaginalis: a meta-analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24(2):111–116. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark JJ, Limm W, Wong LL. What is the likelihood of requiring contralateral inguinal hernia repair after unilateral repair? Am J Surg. 2011;202(6):754–757. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CH, Chen Y, Cheng CF, Yao CL, JC W, Yin WY, Chen JH. Incidence of and risk factors for pediatric Metachronous Contralateral inguinal hernia: analysis of a 17-year Nationwide database in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J-H, Wu J-C, Yin W-Y, Lee C-H. Bilateral primary inguinal hernia repair in Taiwanese adults: a nationwide database analysis. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansaloni L, Coccolini F, Fortuna D, Catena F, Di Saverio S, Belotti LM, Melotti RM. Assessment of 126,913 inguinal hernia repairs in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy: analysis of 10 years. Hernia. 2014;18(2):261–267. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saleh F, Okrainec A, D'Souza N, Kwong J, Jackson TD. Safety of laparoscopic and open approaches for repair of the unilateral primary inguinal hernia: an analysis of short-term outcomes. Am J Surg. 2014;208(2):195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zendejas B, Onkendi EO, Brahmbhatt RD, Greenlee SM, Lohse CM, Farley DR. Contralateral metachronous inguinal hernias in adults: role for prophylaxis during the TEP repair. Hernia. 2011;15(4):403–408. doi: 10.1007/s10029-011-0784-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosas S, Sabeh KG, Buller LT, Law TY, Kalandiak SP, Levy JC. Comorbidity effects on shoulder arthroplasty costs analysis of a nationwide private payer insurance data set. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2017;26(7):e216–e221. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(11):923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin KJ, Harris S, Tang TY, Skelton N, Reed JB, Harris AM. Incidence of contralateral occult inguinal hernia found at the time of laparoscopic trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) repair. Hernia. 2010;14(4):345–349. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saggar VR, Sarangi R. Occult hernias and bilateral endoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: is there a need for prophylactic repair? : Results of endoscopic extraperitoneal repair over a period of 10 years. Hernia. 2007;11(1):47–49. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koehler RH. Diagnosing the occult contralateral inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(3):512–520. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8166-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bochkarev V, Ringley C, Vitamvas M, Oleynikov D. Bilateral laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in patients with occult contralateral inguinal defects. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(5):734–736. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sayad P, Abdo Z, Cacchione R, Ferzli G. Incidence of incipient contralateral hernia during laparoscopic hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(6):543–545. doi: 10.1007/s004640000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stott MA, Sutton R, Royle GT. Bilateral inguinal hernias: simultaneous or sequential repair? Postgrad Med J. 1988;64(751):375–378. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.64.751.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dakkuri RA, Ludwig DJ, Traverso LW. Should bilateral inguinal hernias be repaired during one operation? Am J Surg. 2002;183(5):554–557. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh HK, Kim H, Ryoo S, Choe EK, Park KJ. Inguinal hernia repair in patients with cirrhosis is not associated with increased risk of complications and recurrence. World J Surg. 2011;35(6):1229–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott NW, McCormack K, Graham P, Go PM, Ross SJ, Grant AM. Open mesh versus non-mesh for repair of femoral and inguinal hernia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;4:CD002197. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Veen RN, Wijsmuller AR, Vrijland WW, Hop WC, Lange JF, Jeekel J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of non-mesh versus mesh repair of primary inguinal hernia. Br J Surg. 2007;94(4):506–510. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwaans WAR, Verhagen T, Wouters L, Loos MJA, Roumen RMH, Scheltinga MRM. Groin pain characteristics and recurrence rates: three-year results of a randomized controlled trial comparing self-gripping Progrip mesh and sutured polypropylene mesh for open inguinal hernia repair. Ann Surg. 2017. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002331. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study is based in part on data from National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). The data utilized in this study cannot be made available in the manuscript, the supplemental files, or in a public repository due to the “Personal Information Protection Act” executed by Taiwan’s government, starting from 2012. Requests for data can be sent as a formal proposal to the NHIRD (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw) or by email to nhird@nhri.org.tw.