Abstract

We discuss an unusual case of a large cystic mass arising in the left upper quadrant of a 48-year-old woman. Radiological investigations could not confirm the origin or the nature of the mass. A laparatomy revealed a large retroperitoneal cystic mass sandwiched between the left adrenal, spleen and the gastro-oesophageal junction. Histological analysis confirmed a mature teratoma of the retroperitoneum with neuroendocrine carcinoma arising within it. To our knowledge this is only the second reported case of its kind.

Keywords: Retroperitoneal teratoma, Neuroendocrine carcinoma

Teratomas are a type of germ-cell tumour which may contain embryological tissues from more than one germ-cell layer, namely ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. Teratomas usually occur in the gonads but 1–5% occur in extragonadal sites.1 Rarely, teratomas can be malignant. Here we describe a case of neuroendocrine carcinoma arising in a mature retroperitoneal teratoma. Neuroendocrine carcinomas have been described in teratomas of the gonads2 and sacrococcygeal region.3 To our knowledge, this is only the second reported case of neuroendocrine carcinoma arising in a mature retroperitoneal teratoma.

Case history

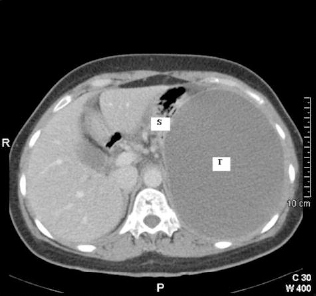

A 48-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a month’s history of pain in the left upper quadrant (LUQ). The pain had increased in severity over a 3-day period and was associated with one episode of bilious vomiting. She did not report any change in bowel habit or per-rectal bleeding. There was no history of dyspepsia, acid reflux symptoms, urinary symptoms, fever, weight loss or night sweats. She had no significant past medical history and was not on any regular medication. Clinical examination revealed a 10-cm, firm, immobile mass in the LUQ. Observations confirmed that she was haemodynamically stable and afebrile. Bloods showed a raised C-reactive protein level of 299 mg/l, however the Full Blood Count, Urea and Electrolytes, and Liver Function Tests were normal. The abdominal radiograph revealed a large space occupying lesion in the LUQ with displacement of bowel loops to the right. An abdominal ultra-sound scan showed a large hypo-echoic mass in the left hypochondrium measuring 15.2 × 11.6 × 14.1 cm. There was a solid echogenic nodule measuring 1.3 cm within the mass with no obvious Doppler flow. A contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomographic (CT) scan (Figs 1 and 2) revealed ascites and a large well circumscribed 14.8 × 17.6 cm mass in the LUQ. The attenuation value of the lesion was less than 25 Hounsfield Units , suggesting a cystic lesion with possibly haemorrhagic or mucinous content. Enhancing soft tissue components were noted in the cyst wall. The lesion displaced the spleen and the left kidney inferiorly and the stomach superiorly. Clear fat planes separating the cyst and the surrounding structures were seen.

Figure 1.

Transverse CT image of abdomen at level of T12 vertebrae. Note the large tumour mass (T) filling the left hemi-abdomen and displacing the stomach (S) superiorly.

Figure 2.

Transverse CT image of mature teratoma (T) at level of L2 vertebrae. Note the spleen (Sp) and left kidney (LK) which have been displaced inferiorly.

A multidisciplinary decision was made to proceed to laparotomy. Operative findings revealed at least 3 litres of turbid fluid in the abdominal cavity and an approximately 15-cm sized cystic mass was seen arising from the retroperitoneum, sandwiched between the left adrenal, spleen and the gastro-oesophageal junction (Fig. 3). The cyst could be easily separated from surrounding structures with no obvious communication or attachment. The cyst wall was ruptured at least in one area explaining the free fluid and perhaps her acute presentation. Cut section revealed viscous chocolate-coloured contents with a smooth cyst wall (Fig. 4). The presence of a small solid area within the cyst wall was noted.

Figure 3.

Laparotomy with retroperitoneal teratoma (T) partly mobilised and adherent to the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ).

Figure 4.

Mature teratoma – cyst wall incised and internal surface displayed.

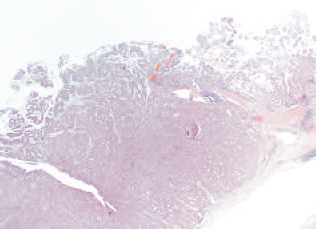

Extensive sampling of the cyst wall showed mature, cystic teratoma represented mostly by mesodermal and endodermal derivatives. Tissue sampled from the largest solid area (12-mm nodule) showed neuroendocrine carcinoma arising within the teratoma (Figs 5 and 6). The resection margins were not involved. She made an uneventful recovery with complete resolution of her symptoms and was subsequently referred to an oncologist for consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Figure 5.

Solid nodule component of cyst wall which displays neuroendocrine morphology (×5, H&E).

Figure 6.

Solid neuroendocrine carcinoma with atypical mitotic figures (arrows; x20, H&E).

The patient has now received three cycles of bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy. Repeat CT at 6 months after diagnosis did not reveal any metastatic disease and she remains disease-free.

Discussion

Primary retroperitoneal teratomas comprise only 5–10% of retroperitoneal tumours4 with bimodal peaks in the first 6 months of life and early adulthood.5 The mean age is 13–16 years; only 10–20% occur above the age of 30 years.4 Twice as many women are affected by retroperitoneal teratomas than men.6

The disease progression is typically asymptomatic as the position of the tumour in the retroperitoneum provides a large space within which to grow and the tumour does not present itself until it is very large, usually more than 5–10 cm in diameter. Presenting symptoms may include an increase in abdominal girth, abdominal pain, back pain, nausea and vomiting, fever, weight loss, urinary retention4,6 and lower extremity/genital swelling due to lymphatic obstruction by the tumour.5 Examination may reveal a palpable abdominal mass.

Abdominal radiograph may reveal a soft tissue mass with displacement of the bowel loops and calcification. Abdominal ultrasonography may show a large complex mass with cystic and solid components. The cystic region

contains sebum and may show a fat-fluid level. CT scan displays fluid, fat and calcium constituents. Irregular wall thickening has been shown to be a marker of malignant potential.4 Magnetic resonance imaging may improve soft tissue resolution and help in predicting resectability.

Teratomas are congenital, they develop from primordial germ cells. These totipotent cells differentiate to form tissue components of mesoderm, ectoderm and endoderm. At week 4 of gestation, germ cells migrate down the fetal mid-line to reach the gonads. It is thought that, during this embryological migration, some of the cells can arrest and survive in an extragonadal location, mainly at mid-line sites.5 That is why 1–5% of cases1 are found in extragonadal sites. In order of frequency these sites are: anterior mediastium, retroperitoneal, sacrococcygeal and intracranial.5,6

Macroscopically, teratomas are encapsulated, large, hetero-geneous masses with both solid and cystic components. The cystic areas may contain serous or mucinous keratinaecous fluid with small areas of calcification. Teratomas are classified on the basis of their histopathological findings and can be divided into two categories – mature and immature – which contain adult and embryonic type tissues, respectively.5

Extragonadal teratomas are generally benign with an approximate 25% risk of malignant transformation.5 A malignant tumour arising within an existing mature teratoma is called teratoma with malignant transformation (TMT). The malignancy can arise either from undifferentiated embryonic tissue or somatic differentiated tissue with-in the teratoma. Embryonic tissue malignancies include germinoma, choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumour and embryonal carcinoma. Somatic tissue malignancies include sarcomas and carcinomas.1 Neuroendocrine carcinoma within a teratoma is extremely rare.

The main-stay of treatment for a retroperitoneal teratoma is surgical resection. Presence of embryonic tissue malignancy will generally indicate cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy.5 If there is somatic tissue malignancy within the teratoma, there does not appear to be a standard regimen for the use of chemotherapy. The choice of adjuvant chemotherapy in such a scenario will be dictated by the exact histology, for example, the use of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma.7

In general the prognosis of TMT is considered to be good if the tumour is completely excised will no capsular breach. The predicted 5-year survival following a curative resection is approximately 90% if there are no metastases and tumour marker levels (alpha-fetoprotein or beta-human chorionic gonadotropin) are low. This may drop to 75% if there is no distant disease but intermediate tumour markers and 50% if the tumour has metastasized.8 Neuro-endocrine tumours arising in mature teratomas are considered to be of low malignant potential;6 however, their specific prognosis remains unclear. Further follow-up of cases such as this is required in order to accumulate enough data to predict this.

References

- 1.McKenny JK, Heerema-McKenney A, Rouse RV. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: a review with emphasis on pathologic features, clinical prognostic variables, and differential diagnostic considerations. Adv Anat Pathol 2007; : 69–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robboy SJ, Norris HJ, Scully RE. Insular carcinoid primary in the ovary. A clini-copathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer 1975; : 404–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arazi M, Toy H, Tavli L. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma arising within a mature sacrococcygeal teratoma. Orthopaedics 2007; : 878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Chu S, Ng K, Wong Y. Adenocarcinomas arising from primary retroperitoneal mature teratomas: CT and MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2002; : 1546–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatcombe HG, Assikis V, Kooby D, Johnstone P. Primary retroperitoneal teratomas: a review of the literature. J Surg Oncol 2004; : 107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamasaki T, Yagihashi Y, Shirahase T, Hashimura T, Watanabe C. Primary carcinoid tumour arising in a retroperitoneal mature teratoma in an adult. Int J Urol 2004; : 912–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donadio AC, Motzer RJ, Bajorin DF, Kantoff PW, Sheinfield J, Houldsworth J et al. Chemotherapy for teratoma with malignant transformation. J Clin Oncol 2003; : 4285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. J Clin Oncol 1997; : 594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]