Abstract

We report a case of appendiceal intussusception which was erroneously labelled as a 10-mm polypoid caecal lesion on colonoscopy and, therefore, followed up over an 11-year period before the correct diagnosis was made. We present the radiological and endoscopic appearance of appendiceal intussusception and a review of the literature.

Keywords: Appendiceal intussusception, Polyp, Colonoscopy

Intussusception of the vermiform appendix is a rare condition, with an approximate incidence of 0.01%. It can mimic several clinical conditions including acute appendicitis or be mistaken as a caecal polypoid lesion on radiological imaging and endoscopy. Correct diagnosis is paramount in order to prevent unnecessary and potentially catastrophic interventions such as endoscopic excision. Despite the availability of various investigative modalities including barium enema, transabdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) colonogram and colonoscopy,1,2 the diagnostic accuracy remains poor. We report a case of appendiceal intussusception which was erroneously labelled as a 10-mm polypoid caecal lesion on colonoscopy and, therefore, followed up over an 11-year period before the correct diagnosis was made. We present the radiological and endoscopic appearance of appendiceal intussusception and a review of the literature.

Case history

A 49-year-old Caucasian woman with a strong family history of colon cancer presented to the colorectal clinic in 1997 with a several year history of constipation and mild abdominal pain. A barium enema showed a long and tortuous colon with a polypoid lesion in the caecum. A subsequent colonoscopy was technically challenging but successful and confirmed the presence of a 10-mm ‘polypoid lesion’ in the caecum. Multiple biopsies were taken and showed normal colonic mucosa.

Because of doubt about its nature and in view of the difficulties met on previous colonoscopy, this lesion was followed up with serial barium enemas. It remained unchanged until 2008, when a fourth barium enema showed an increment in size and in fact a subsequent CT colonogram confirmed the lesion to be 18.2 mm at its base and 11.1 mm in anteroposterior depth (Fig. 1). A second colonoscopy was, therefore, performed with a view to endoscopic excision. However, on this occasion, the lesion was recognised as an intussuscepted appendix and multiple biopsies confirmed normal colonic mucosa (Fig. 2). The diagnosis become more obvious as the length of the intussusception increased on retraction with biopsy forceps (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

CT colonogram view of the caecal pole showing the intussuscepted appendix.

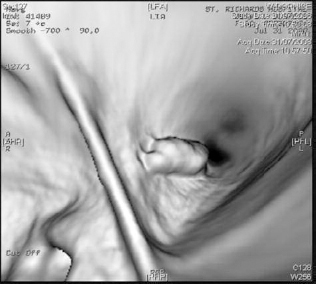

Figure 2.

Intussuscepted appendix resembling a polypoid lesion during colonoscopy.

Figure 3.

Figure 3 Further intussusception on retraction with biopsy forceps.

Discussion

The first case of intussusception of the vermiform appendix was reported in a 7-year-old boy by McKidd in 1858. In 1964, Collins and colleagues reported a prevalence of 0.01% after concluding a 40-year study including 71,000 surgically removed and cadaveric appendices. The majority of cases of appendiceal intussusception reported in the literature have been in paediatric patients, with an average age of 16 years. Furthermore, it is diagnosed in the first decade and is typically four times more common in males than in females.3

Patients with appendiceal intussusception typically experience non-specific symptoms including recurrent cramping abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, melaena and mucous in stools, and altered bowel habit. Four types of presentation have been described. The first type mimics, and is often confused with, acute appendicitis. The second type includes typical features of intussusception: a several day history of abdominal pain and vomiting with or without diarrhoea and melaena. In type 3, patients describe a several month history of recurrent right lower quadrant pain, vomiting and malaena.3 Type 4 refers to a minority of patients who remain asymptomatic and are incidentally diagnosed with the abnormality.1

Although the pathogenesis of appendiceal intussusception remains unknown, local irritation leading to abnormal peristalsis of the caecum or the appendix itself is thought to play a key role.1 Irritation may result from foreign bodies, faecoliths, polyps and lymphoid hyperplasia possibly due to cystic fibrosis, in both children and adults. Associations with endometriosis, adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumours and mucocoeles have also been reported in adults.4 Anatomical abnormalities such as a mobile mesoappendix or a wide appendiceal lumen may also cause intussusception.1

In 1958, Langsam et al. proposed a simple classification for appendiceal intussusception. Type I begins at tip of the appendix (the intussusceptum) which intussuscepts into its more proximal portion (the intussuscipiens). Type II begins in the base of the appendix (intussusceptum) and the caecum is the intussuscipiens. In type III, the base of the appendix is the intussusceptum received by the appendiceal tip. Type IV refers to complete inversion of the appendix with accompanying ileocaecal intussusception, whereby the appendix remains the leading point of the intussusceptum. This can result from Types 1 and 2 intussusception.

Different radiological investigations including barium enema, ultrasonography and CT have been utilised in the diagnosis of appendiceal intussusception.2 Findings such as absent appendiceal filling or a coiled spring appearance in the caecum on double-contrast barium enema have been described.1,3 Features such as ‘target-like’ appearance and the ‘concentric ring sign’ on axial ultrasonography have been described in the literature.1,3 Furthermore, an inverted appendix intruding into the caecum may be observed on longitudinal ultrasound.1 However, absent filling on barium enema is neither sensitive nor specific in the diagnosis of intussusception.

There are several reports in the literature of appendiceal intussusception being diagnosed on colonoscopy.1 Its appearance is commonly referred to as polypoid; however, the intussusceptions may reduce on insufflation of air during colonoscopy, resulting in a halo-like erythematous region surrounding the appendiceal lumen.3 However, there are also reports of cases of appendiceal intussusception misdiagnosed endoscopically as a caecal polyp or carcinoma.

Conclusions

Correct diagnosis of appendiceal intussusception is vital in avoiding unnecessary and potentially catastrophic interventions like endoscopic excision or even more radical surgery in cases of suspected malignancy. In symptomatic patients, laparoscopic appendicectomy is effective and low in risk. Successful endoscopic appendicectomy has also been described in the literature. However, in our opinion, surgical intervention is unnecessary in patients with long-standing asymptomatic appendiceal intussusception.

References

- 1.Ozuner G, Davidson P, Church J. Intussusception of the vermiform appendix: preoperative colonoscopic diagnosis of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Colorectal Dis 2000; : 185–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swanger R, Davis S, McBride W, Rachlin S, Sonke PY, Brudnicki A. Multimodality imaging of an appendiceal intussusception. Pediatr Radiol 2007; : 929–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavakkoli H, Sadrkabir SM, Mahzouni P. Colonoscopic diagnosis of appendiceal intussusception in a patient with intermittent abdominal pain: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2007; : 4274–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Offodile A 2nd, Hodgin JB, Arnell T. Asymptomatic intussusception of the appendix secondary to endometriosis. Am Surg 2007; : 299–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]