Abstract

A 53-year-old Cambodian woman presented with nodular masses on the right arm suggestive of a sarcoma-type malignancy. The masses were excised and identified as multiple benign eccrine poromas. The patient re-presented after two years with large relapsed tumours and axillary lymph node involvement. A forequarter amputation was undertaken. Histology confirmed the diagnosis of a porocarcinoma, which was likely to be due to malignant transformation of the original poromas. The size and multiplicity of the tumours represents a highly unusual presentation of these rare eccrine neoplasms.

Keywords: Porocarcinoma, Eccrine, Poroma, Sarcoma

Case history

A 53-year-old Cambodian woman presented with a 2-year history of progressively enlarging multiple nodular masses on the right arm (Fig 1). No concurrent loss of weight was reported but prominent axillary lymph nodes were noted on examination. Plain radiography of the arm did not reveal bone involvement and there was no evidence of lung metastases on plain chest films.

Figure 1.

Initial presentation of tumours

An initial biopsy specimen was misidentified as a primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET). The masses were excised and reclassified after further histological examination as a poroma or poromatosis. A ‘watch and wait’ approach was adopted. The patient returned two years later with recurrence of ulcerated masses comparable in size with the initial presentation, in addition to a new large tumour in the upper arm (15.5cm x 12cm x 10cm) (Fig 2). There was no neurological deficit but because of the weight of the tumours, the patient had learned to preferably use her non-dominant left hand. Staging radiography of the arm and chest did not reveal any new findings.

Figure 2.

Presentation after relapse

Owing to the likelihood of malignancy, a forequarter amputation was performed. Histology of the resected specimen showed an advanced porocarcinoma involving axillary lymph nodes (Figs 3 and 4). One year later, relapse was identified in an ipsilateral cervical lymph node, which was subsequently excised. The patient was referred for chemotherapy but died with metastatic disease approximately 34 months after the amputation.

Figure 3.

Histology of relapsed tumour (20x magnification) showing rounded monomorphic cells typical of a classical poroma displaying bland cytology. It is notable that the overall morphology is atypical in this case owing to a lack of mitoses and paucity of duct formation.

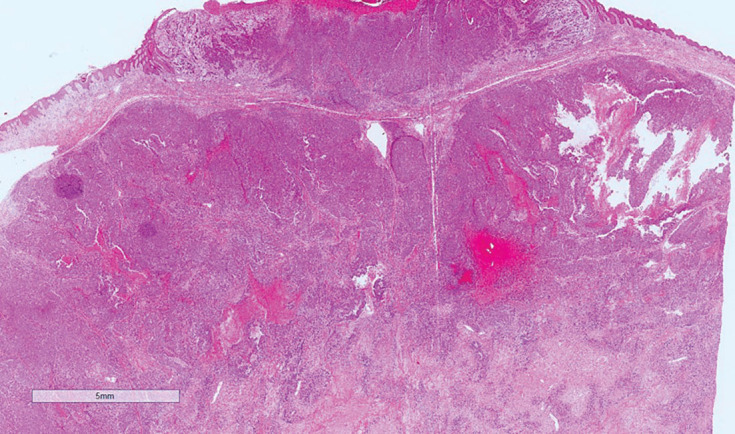

Figure 4.

Histology (4x magnification) showing ulcerated tumour with invasion of the dermis and epidermal attachment

Discussion

Porocarcinoma and its benign counterpart eccrine poroma are rare neoplasms arising from the eccrine sweat glands. The former only represents approximately 0.005% of all cases of epithelial cutaneous cancer.1

Typically presenting as a solitary, firm, erythematous to violaceous nodule around 2cm in diameter, poromas are most often found on the lower limbs but with cases on the head, scalp, upper limbs, trunk and abdomen also being reported.1 Approximately 50% of eccrine porocarcinoma cases develop from existing benign lesions, with the clinical presentation of malignant change being bleeding, itching and rapid growth,2 and the tumour taking on a typically more ulcerated and exophytic appearance.

Microscopically, porocarcinomas are classically described as a collection of anaplastic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, extending from the epidermis to the dermis, and they are sometimes found in proximity to the palisades of cuboidal and poroid cells typical of a benign poroma. Benign poromas are known to have characteristics more commonly found in malignant lesions such as necrosis and mitoses, leading to misclassifications.2 Similarly, porocarcinomas can be mistaken for benign because of a lack of these features.3

Porocarcinomas do not seem to show a propensity to affect any particular sex or ethnicity, and the incidence peaks between the ages of 60 and 80 years. There is currently no evidence to suggest a hereditary component to the disease. Several authors have suggested an association with radiation exposure and immunosuppression but excessive sun exposure does not seem to be a risk factor.1 On the rare occasion that multiple poromas are present, this phenomenon is described as poromatosis. As of 2013, only nine cases have been reported in the literature, with most patients having had some form of immunosuppression.4 In our case, no obvious patient risk factors were present, the patient was not immunocompromised and she had not previously undergone radiotherapy.

The mainstay of management is surgical excision, with cure rates of 70–80%.3,5 The majority of these lesions can be locally excised; other techniques such as Mohs micrographic surgery (in which sequential thin layers of skin are excised and examined for tumour margins to limit resection) have also been shown to be of benefit.1 It is unusual for the tumours to be so extensive that amputation is required. The reason for the delay in presentation with recurrence is unclear but it could possibly be down to the logistics of accessing healthcare in a resource poor setting or a result of fear of amputation. Owing to certain cultural beliefs, patients in Cambodia may refuse amputation even in life threatening situations.

Features that have been suggested to indicate a poorer prognosis are high mitotic activity and depth greater than 7mm.3 Porocarcinoma is thought to have a 20% rate of lymph node spread and a 10% rate of distant metastases.3 The outcome is very poor in these cases. However, successful management with docetaxel has been described in a case of disseminated disease where platinum-based agents had failed.6

To date, virtually all descriptions of porocarcinoma and poromatosis are of discrete skin lesions, and they are often mistaken for the more common diseases that present in this manner (eg squamous cell carcinoma).3 Consequently, their management is often the remit of dermatologists and it is unusual for such a case to cross into the domain of surgeons.

At first presentation, the tumour was (understandably) mistaken clinically for a sarcoma and then histologically as a PNET. Cases of massive soft tissue sarcomas are abundant whereas there are very few reports of benign or malignant eccrine poromas reaching this size, with the largest described at 20cm.3 Lymph node involvement in this case is in keeping with a porocarcinoma; PNETs or other sarcomas typically display haematogenous spread. In the developed world, this patient would have had full computed tomography staging prior to surgery. Owing to a scarcity of these services in Cambodia, a substitute of clinical and radiographic examination was employed, and it was therefore difficult to ascertain an accurate disease stage at each presentation.

The macroscopic appearance of a violaceous nodule with multiple exophytic features clearly fits with the literature description of porocarcinoma but the reasons for its massive size and multiplicity are still unclear. In this case, the histological feature defining the diagnosis of porocarcinoma is the rounded, monomorphic poroid cell population, clearly invasive and metastatic. However, it is atypical in that the cells are not anaplastic or palisaded in appearance. Malignant transformation of the originally identified poroma in this patient seems likely and the rapid recurrence after excision is a feature described in other cases of porocarcinoma.3

Conclusions

This case highlights the importance of careful clinical and histological diagnosis. When presented with a large soft tissue mass, it is necessary to consider rare causes. Masquerading as a sarcoma-type malignancy in a unique presentation, the porocarcinoma in our patient is one of the largest described to date.

References

- 1.Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol 2014: : 1,053–1,061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown CW, Dy LC. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatol Ther 2008; : 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; : 710–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deckelbaum S, Touloei K, Shitabata PK et al. Eccrine poromatosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol 2014; : 543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen A, Nguyen AV. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Cutis 2014; : 43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aaribi I, Mohtaram A, Ben Ameur El Youbi M et al. Successful management of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. Case Rep Oncol Med 2013; 282536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]