Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Selective non-operative management (SNOM) of abdominal stab wounds is well established in South Africa. SNOM reduces the morbidity associated with negative laparotomies while being safe. Despite steady advances in technology (including laparoscopy, computed tomography [CT] and point-of-care sonography), our approach has remained clinically driven. Assessments of financial implications are limited in the literature. The aim of this study was to review isolated penetrating abdominal trauma and analyse associated incurred expenses.

METHODS

Patients data across the Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Trauma Service (PMTS) are captured prospectively into the regional electronic trauma registry. A bottom-up microcosting technique produced estimated average costs for our defined clinical protocols.

RESULTS

Between January 2012 and April 2015, 501 patients were treated for an isolated abdominal stab wound. Over one third (38%) were managed successfully with SNOM, 5% underwent a negative laparotomy and over half (57%) required a therapeutic laparotomy. Over five years, the PMTS can expect to spend a minimum of ZAR 20,479,800 (GBP 1,246,840) for isolated penetrating abdominal stab wounds alone.

CONCLUSIONS

Provided a stringent policy is followed, in carefully selected patients, SNOM is effective in detecting those who require further intervention. It minimises the risks associated with unnecessary surgical interventions. SNOM will continue to be clinically driven and promulgated in our environment.

Keywords: Penetrating abdominal trauma, Cost

Selective non-operative management (SNOM) of abdominal stab wounds is well established in South Africa.1,2 Despite steady advances in technology (including laparoscopy, computed tomography [CT] and point-of-care sonography), our approach to penetrating torso trauma has remained clinically driven. SNOM arose as a result of a massive imbalance between the burden of trauma encountered by surgeons and the limited resources available.3 The outcomes of SNOM have been extensively published.2–5 It has been shown to reduce the morbidity associated with negative laparotomy while being extremely safe.6 However, little has been published on the potential cost savings associated with this approach. In an era where financial constraints impact so significantly on healthcare systems worldwide, it is important to be able to demonstrate that a management algorithm is both safe and cost effective.

The objective of this study was twofold. First, we review our experience with SNOM to to determine whether this approach remains valid and effective in the modern era, and to determine whether any modern technologies may assist us in refining our approach. Second, we wished to cost the management of abdominal stab wounds in our environment.

Setting

This was a retrospective study undertaken at the Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Trauma Service (PMTS), Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Our electronic regional trauma registry (HEMR – Hybrid Electronic Medical Records) was reviewed from January 2012 to April 2015. Ethics approval for this study and for maintenance of the registry was formally endorsed by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) of the University of KwaZulu Natal (reference: BE 207/09). The PMTS provides definitive trauma care to the city of Pietermaritzburg, the capital of KwaZulu Natal (KZN) province. It also serves as the major trauma referral centre for nineteen other rural hospitals within the province, with a total catchment population of over three million. Approximately 3,000 trauma cases are admitted to the PMTS per annum, with over 40% penetrating trauma. This is a direct reflection of the high incidence of interpersonal violence and serious crime experienced throughout the entire province. Weekly morbidity and mortality meetings and stringent clinical management protocols ensure that optimal and universal care is maintained.

Management protocols

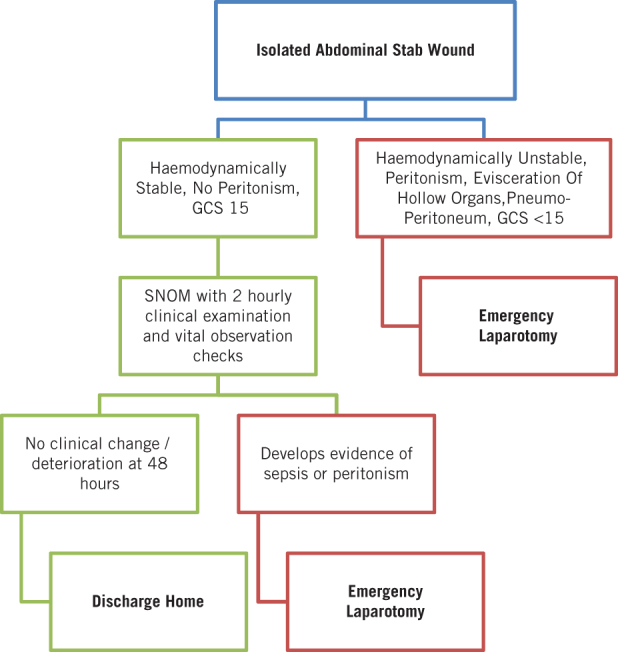

In our unit, every patient who presents with an abdominal stab wound is resuscitated by our receiving staff according to Advanced Trauma Life Support® principles.7 Patients are then managed based on a set algorithm (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Management algorithm for penetrating abdominal wounds

All patients who are haemodynamically unstable, peritonitic, with eviscerated hollow organs or with pneumoperitoneum are expedited directly to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. In the absence of one of these features, all patients are admitted. All patients are kept nil by mouth, and given intravenous fluids and analgesia. The same admitting surgeon then observes them meticulously every 2 hours for the next 12 hours. After this trial period, if they remain stable and have no features of peritonitis, they are fed and observed for a further 12–24 hours. At the end of this 48-hour period of observation, if they are well, they are discharged.

Omental evisceration can be managed in conjunction with other clinical findings and is not an immediate indicator for emergency laparotomy.8,9 It alerts the surgeon to an increased likelihood of intra-abdominal pathology9 and the need for increased vigilance with serial examinations. However, in an alert, haemodynamically stable patient, with no peritonism or associated visceral herniation, PMTS practice is for the omentum to be washed thoroughly and replaced intra-abdominally or amputated, as appropriate. Huizinga et al have demonstrated that this technique does not increase morbidity or hospital stay.8

Methods

All patients who sustained an isolated abdominal stab wound over a 40-month period from January 2012 to April 2015 were identified for review. Standard demographic data were recorded for each case. The clinical management of each patient was reviewed and the clinical outcome documented.

Costing

The primary author performed a bottom-up microcosting analysis for a cohort of 46 index patients. Generation of a number of general equations for four specific clinical scenarios (successful SNOM, negative laparotomy, simple laparotomy and complex laparotomy) established the average cost. Eight cost drivers were identified: inpatient stay, operative costs, laboratory and radiological investigations, ward adjuncts, blood transfusion and blood product use, antimicrobial use and analgesic requirements. The cost drivers and corresponding costs are listed in Table 1. These were based on discussion with individual finance officers and consultation with private health insurers. All costs pertain to previously published data from our institution.10,11

Table 1.

Cost drivers. (Figures rounded up to nearest 10 for both ZAR and GBP; Currency conversion rates as at 22 February 2017: http://www.google.com/finance/converter)

| Cost driver | Cost | |

| ZAR | GBP | |

| 1. Operative10 | ||

| Operative time (per minute) | 110 | 7 |

| Operative sundries (per hour) | 230 | 14 |

| 2. Analgesia10 | ||

| Analgesia (per day) | 50 | 3 |

| 3. Antimicrobials (per day)10 | ||

| Co-amoxiclav | 100 | 6 |

| Gentamicin | 60 | 4 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 650 | 40 |

| Fluconazole | 750 | 46 |

| 4. Laboratory investigations (per test)11 | ||

| Full blood count | 50 | 3 |

| Blood gas analysis | 50 | 3 |

| Urine dip/microscopy, culture and sensitivity | 50 | 3 |

| Urea and electrolytes | 70 | 4 |

| Calcium, magnesium, phosphate | 80 | 5 |

| Liver function test | 160 | 10 |

| Coagulation | 260 | 16 |

| 5. Ward adjuncts (per single item)11 | ||

| Central venous catheter | 280 | 17 |

| Intercostal drain | 150 | 9 |

| Urinary catheter | 40 | 2 |

| Peripheral intravenous cannula | 30 | 2 |

| Nasogastric tube | 1 | 0.1 |

| 6. Radiological investigations11 | ||

| X-ray (chest) | 250 | 15 |

| X-ray (abdomen) | 270 | 16 |

| CT angiography | 6,280 | 382 |

| CT (thorax) | 2,140 | 130 |

| CT (abdomen) | 2,120 | 129 |

| CT (head, cervical spine, thorax, abdomen, pelvis) | 10,410 | 634 |

| 7. Inpatient stay (per day)10 | ||

| Ward | 1,250 | 76 |

| High care (ICU/HDU) | 8,000 | 487 |

| 8. Blood and blood products11 | ||

| 1 unit of packed RBC or use of cell save machine | 1,850 | 113 |

CT = computed tomography; HDU = high dependency unit; ICU = intensive care unit; RBC = red blood cells

The costs include all overhead expenses such as water and electricity but not staff salaries. It was not possible to include the cost of vital services provided by allied health professionals such as physiotherapists, dieticians and occupational therapists, making our calculations a conservative estimate of the true total. Inpatient stay was costed at ZAR 1,250 (GBP 80) for the ward and ZAR 8,000 (GBP 490) for high care (intensive care unit [ICU] or high dependency unit [HDU]).10 Theatre time was costed at ZAR 110 (GBP 7) per minute plus ZAR 230 (GBP 20) per hour for operative sundries. Laboratory investigations, blood transfusions, medications and total parental nutrition were priced directly from the laboratory, blood bank, pharmacy and dietetic hospital department pricing lists. Ward adjunct costs were calculated using the ward stock checklist.

Based on the costs and the cost drivers for the 46 patients, the primary author established the average cost of SNOM, a negative laparotomy, a single simple laparotomy and a complex laparotomy case. Any patient who had more than three intra-abdominal injuries or who required a repeat laparotomy was defined as a complex patient. The primary author also estimated the cost of managing the SNOM cohort compared with a number of other described approaches. These included mandatory laparotomy, additional mandatory CT and additional mandatory diagnostic laparoscopy.

Results

A total of 501 patients were treated with an isolated abdominal stab wound over the 40-month period under review. Of this cohort, 38% were managed successfully by SNOM. The rest were managed operatively; 5% underwent a negative laparotomy, 43% a single simple laparotomy, and 14% had more than three injuries or required more than one laparotomy and were classified as complex laparotomies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of patient demographics and weapons used

| SNOM (n=189, 38%) | Negative laparotomy (n=27, 5%) | Simple laparotomy (n=214, 43%) | Complex laparotomy (n=71, 14%) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age (range) in years | 28 (6–68) | 28 (16–53) | 28 (10–63) | 28 (15–53) |

| Sex ratio | 19 F: 170 M | 4 F: 23 M | 13 F: 201 M | 8 F: 63 M |

| Mean admission pulse (range) in bpm | 81 (47–119) | 83 (54–120) | 92 (54–213) | 102 (57–135) |

| Mean admission GCS (range) | 15 | 14 (9–15) | 14 (6–15) | 14 (3–15) |

| Mean admission lactate (range) in mmol/l | 2.0 (0.7–12) | 2.1 (0.8–3.9) | 3.0 (0.5–36) | 3.9 (0.7–9.3) |

| Mean injury severity score (range) | 3.4 (1–16) | 5.2 (1–16) | 9.0 (2–25) | 14.0 (3–34) |

| Intensive care unit | 0% | 4% | 10% | 39% |

| High dependency unit | 0% | 4% | 3% | 13% |

| Survival rate | 100% | 100% | 96% | 93% |

| Weapons | ||||

| Knife | 139 | 23 | 153 | 43 |

| Bottle | 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Spear | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| Bush knife | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Screwdriver | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Unknown | 27 | 4 | 45 | 21 |

GCS = Glasgow coma scale; SNOM = selective non-operative management

Selective non-operative management group

A total of 189 patients (38%) were managed using this non-operative approach. For these cases, the mean age was 28 years (range: 6–68 years) with the usual male preponderance (89%). All had an admission Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 15 and the mean admission heart rate was 81bpm (range: 47–119bpm). Six per cent had omental evisceration. Investigation of the weapons used revealed that 74% of the SNOM cohort sustained knife wounds, 6% sustained bottle injuries and 6% had injuries from other implements. The weapon was unknown in 14% of the cases. All patients survived with no complications.

Negative/non-therapeutic laparotomy group

A total of 27 patients (5%) underwent a negative/non-therapeutic laparotomy. They had very similar demographics to those in the SNOM cohort. The mean age was 28 years (range: 16–53 years), 85% were male, 85% sustained injuries from knife wounds and the mean admission pulse rate was 83bpm (range: 54–120bpm). The noticeable difference was in the admission GCS score. Three cases (11%) had no admission GCS score recorded. Twenty-one cases (78%) had an admission GCS score of 15 and underwent an exploratory laparotomy as they developed clinical signs of peritonism during their period of observation. Three cases (11%) had an admission GCS score of <15 (9, 12 and 14) and were therefore not suitable candidates for SNOM because of the inability to clinically assess the abdomen on admission. Eight per cent of cases required high care (ICU/HDU) despite there being no intra-abdominal pathology.

Therapeutic laparotomy group (simple and complex cases)

The increased mean admission pulse rate and lactate and the reduced mean GCS score of these patients reflect the severity of their underlying injuries. The rate of ICU/HDU admission was also significantly higher than for the other cohorts, as expected (13% for simple laparotomy and 52% for complex laparotomy).

Cost per procedure

Using the 46 index cases, an average cost was generated for successful SNOM, negative laparotomy, simple laparotomy, complex laparotomy and diagnostic laparoscopy. These are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Estimated average overall costs for selected management algorithms used in penetrating abdominal stab wounds. (Figures rounded up to nearest 10 for both ZAR and GBP; Currency conversion rates as at 22 February 2017: http://www.google.com/finance/converter)

| SNOM | Negative laparotomy | Simple laparotomy | Complex laparotomy | Diagnostic laparoscopy | |

| 1. Operative | 0 | 5,300 | 12,600 | 27,440 | 6,930 |

| 2. Analgesia | 540 | 590 | 730 | 990 | 600 |

| 3. Antimicrobials | 20 | 60 | 1,010 | 2,700 | 0 |

| 4. Laboratory investigations | 250 | 260 | 810 | 2,620 | 230 |

| 5. Ward adjuncts | 100 | 140 | 130 | 1,010 | 140 |

| 6. Radiological investigations | 730 | 420 | 690 | 970 | 360 |

| 7. Inpatient stay | 5,000 | 6,000 | 10,000 | 49,500 | 6,000 |

| 8. Blood and blood products | 0 | 0 | 1,320 | 2,270 | 0 |

| Total (ZAR) | 6,640 | 12,770 | 27,290 | 87,500 | 14,260 |

| Total (GBP) | 410 | 780 | 1,670 | 5,330 | 870 |

SNOM = selective non-operative management

Actual costs

Based on the figures in Table 3, the total estimated cost was calculated for each of the 4 outcomes over the 40-month study period (Table 4). In order to allow five-year projections, approximations of the average monthly expenses were calculated. This revealed that the estimated average expense over a five-year period for managing isolated abdominal trauma secondary to stab wounds will cost our department a minimum of ZAR 20,479,800 (GBP 1,246,840) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Overall estimated expense for managing abdominal stab wounds across the Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Hospitals Complex. (Figures rounded up to nearest 10 for both ZAR and GBP; Currency conversion rates as at 22 February 2017: http://www.google.com/finance/converter)

| Management algorithm | Number of cases (n=501) | Estimated expense for cohort | |

| ZAR | GBP | ||

| SNOM | 189 | 1,254,960 | 76,410 |

| Negative laparotomy | 27 | 344,790 | 21,000 |

| Simple laparotomy | 214 | 5,840,060 | 355,560 |

| Complex laparotomy | 71 | 6,212,500 | 378,230 |

| Total estimated expense for abdominal stab wounds | 13,552,310 | 825,100 | |

SNOM = selective non-operative management

Table 5.

Projected costs for management of abdominal stab wounds. (Figures rounded up to nearest 10 for both ZAR and GBP; Currency conversion rates as at 22 February 2017: http://www.google.com/finance/converter)

| Management algorithm | Total expense for 40 months | Average expense per month | Average expense per year | Projected 5-year expense | ||||

| ZAR | GBP | ZAR | GBP | ZAR | GBP | ZAR | GBP | |

| SNOM | 1,254,960 | 76,410 | 31,380 | 1,910 | 376,560 | 22,930 | 1,882,800 | 114,630 |

| Negative laparotomy | 344,790 | 21,000 | 8,620 | 530 | 103,440 | 6,300 | 517,200 | 31,490 |

| Simple laparotomy | 5,840,060 | 355,560 | 146,010 | 8,890 | 1,752,120 | 106,680 | 8,760,600 | 533,360 |

| Complex laparotomy | 6,212,500 | 378,230 | 155,320 | 9,460 | 1,863,840 | 113,480 | 9,319,200 | 567,370 |

| Total estimated expense for abdominal stab wounds over next 5 years | 20,479,800 | 1,246,840 | ||||||

SNOM = selective non-operative management

Cost savings

The costs for three alternative management strategies were estimated in order to assess the cost savings for our SNOM regimen. These alternative strategies included additional mandatory abdominal CT, a mandatory exploratory laparotomy (effectively, a negative/non-therapeutic laparotomy) and an additional mandatory diagnostic laparoscopy. The costs are detailed in Table 6. If the PMTS were to adopt a policy whereby all patients with abdominal stab wounds routinely undergo a mandatory diagnostic laparoscopy, not only would the limited theatre resources be saturated but also additional costs would be encountered of over ZAR 2.5 million (GBP 152,210). Furthermore, patients would be subjected unnecessarily to all the risks associated with surgery, including general anaesthesia and surgical complications.

Table 6.

Estimated expense for alternative management algorithms and cost savings with current SNOM protocol for study cohort. (Figures rounded up to nearest 10 for both ZAR and GBP; Currency conversion rates as at 22 February 2017: http://www.google.com/finance/converter)

| Alternative algorithm | Additional individual expense per patient | Estimated expense per patient | Overall estimated expense for 189 SNOM patients | Cost savings | ||||

| ZAR | GBP | ZAR | GBP | ZAR | GBP | ZAR | GBP | |

| Additional mandatory abdominal CT | 2,120 | 130 | 8,760 | 540 | 1,655,640 | 100,800 | 400,680 | 24,400 |

| Additional mandatory diagnostic laparoscopy | 14,260 | 870 | 20,900 | 1,280 | 3,950,100 | 240,490 | 2,695,140 | 164,090 |

| Mandatory exploratory laparotomy (non-therapeutic) | 12,770 | 780 | 12,770 | 780 | 2,413,530 | 146,940 | 530,730 | 32,320 |

CT = computed tomography; SNOM = selective non-operative management

Discussion

Mandatory laparotomy for a penetrating abdominal injuries results in a high rate of negative exploration and has generally been abandoned as an approach.3,5,12 The complication rate for non-therapeutic laparotomies for trauma is not insignificant. Rates vary within the literature, and have been quoted between 15%13 and 33%.12 There is a consensus that patients with active haemorrhage, shock, peritonitis, radiological evidence of visceral perforation or evisceration of hollow viscera require urgent operative exploration.5,9,14 The assessment of stable patients with an abdominal stab wound has been more controversial although SNOM is increasingly accepted.6

The burden of injury in South Africa is large and the resources to deal with it are finite. Consequently, SNOM based on repeated clinical assessment and detection of clinical deterioration was developed as a surgical philosophy, and has been practised for over half a century.1,2 During this time, the burden of trauma has remained constant, with interpersonal violence being ranked the second leading single cause for disability adjusted life years in South Africa.15 Over the last 50 years, a number of modalities and technologies have been introduced. These include diagnostic peritoneal lavage, abdominal CT, abdominal ultrasonography and diagnostic laparoscopy. There is ongoing controversy regarding their role in managing penetrating abdominal trauma.12

The PMTS has selectively adopted some of these for specific clinical problems but detailed clinical assessment has mostly continued as the bedrock of our approach. This report confirms that our clinically driven SNOM approach remains effective and safe. Patient selection criteria must be stringent and strictly adhered to, and clinical examinations must be regular, comprehensive and (ideally) performed by the same trauma surgeon.14 Over a third of our cohort who sustained an abdominal stab wound under these principles and the clinical criteria detailed in Figure 1 were managed successfully without recourse to surgery.

In addition, this study has shown that this approach is, as expected, cost effective. Two described techniques exist for calculating direct costs: a macro (top-down) approach and a mirco (bottom-up) approach. The top-down method uses the overall institutional expense and divides this by the number of individuals treated. Microcosting is time consuming and laborious. It involves attention to detail in the collection and summation of individual resource consumption. It is therefore regarded as the gold standard for costing inpatient stays. Unsurprisingly, a health economics study demonstrated considerable differences in cost calculations between these two techniques.16

A period of SNOM incurs approximately half the expense (as per our microcosting estimates) of performing a negative laparotomy. A number of modalities are used in other settings to manage these cases, including mandatory laparotomy, mandatory abdominal CT and mandatory diagnostic laparoscopy. If the PMTS were to adopt any of these three approaches, it would incur significant and unnecessary expense. If all patients managed with SNOM had a diagnostic laparoscopy, an extra cost of over 2.5 million ZAR (GBP 152,210) would be incurred. This would also expose patients to the risk of unnecessary operative complications (short and long-term), which would inevitably be associated with further financial and social implications that are impossible to quantify accurately.

The applicability of this approach to centres in high income countries still needs to be ascertained. Strategies may be context dependent and cannot be transposed blithely from one setting to the next. Nevertheless, staff in high income countries must be careful not to jettison detailed serial clinical assessment in favour of routine ‘snapshot’ CT for all patients with penetrating injuries. Shift work, busy schedules and incomplete handover can easily result in error. However, thorough bedside clinical examination can detect subtle and dynamic changes, and remains an essential skill for all surgeons involved in trauma care. It should always play an important role in any management strategy for penetrating trauma.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the SNOM approach to the management of abdominal stab wounds is both safe and effective. In addition, it is associated with significant cost savings. SNOM will continue to be clinically driven and actively promulgated in our environment.

Disclaimer

VY Kong, JL Bruce, GV Oosthuizen, GL Laing, DL Clarke are all current ATLS instructors.

References

- 1.Shaftan GW. Indications for operation in abdominal trauma. Am J Surg 1960; : 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demetriades D, Rabinowitz B. Selective conservative management of penetrating abdominal wounds: a prospective study. Br J Surg 1984; : 92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke DL, Thomson SR, Madiba TE, Muckart DJ. Selective conservatism in trauma management: a South African contribution. World J Surg 2005; : 962–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmelzer TM, Mostafa G, Gunter OL et al. . Evaluation of selective treatment of penetrating abdominal trauma. J Surg Educ 2008; : 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke DL, Allorto NL, Thomson SR. An audit of failed non-operative management of abdominal stab wounds. Injury 2010; : 488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zafar SN, Rushing A, Haut ER et al. . Outcome of selective non-operative management of penetrating abdominal injuries from the North American National Trauma Database. Br J Surg 2012; (Suppl 1): 155‖164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Surgeons. ATLS® Student Course Manual. 9th edn Chicago: ACS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huizinga WK, Baker LW, Mtshali ZW. Selective management of abdominal and thoracic stab wounds with established peritoneal penetration: the eviscerated omentum. Am J Surg 1987; : 564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yücel M, Özpek A, Yükseka S et al. . The management of penetrating abdominal stab wounds with organ or omentum evisceration: the results of a clinical trial. Ulus Cerrahi Derg 2014; : 207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong V, Aldous C, Handley J, Clarke D. The cost effectiveness of early management of acute appendicitis underlies the importance of curative surgical services to a primary healthcare programme. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013; : 280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkinson F, Kent SJ, Aldous C et al. . The hospital cost of road traffic accidents at a South African regional trauma centre: a micro-costing study. Injury 2014; : 342–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Gumber AO, Wong CS. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of penetrating abdominal trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2016; : 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demetriades D, Hadjizacharia P, Constantinou C et al. . Selective nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal solid organ injuries. Ann Surg 2006; : 620–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Como JJ, Bokhari F, Chiu WC et al. . Practice management guidelines for selective nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma 2010; : 721–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman R, Matzopoulos R, Groenewald P, Bradshaw D. The high burden of injuries in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2007; : 695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clement FM, Ghali WA, Donaldson C, Manns BJ. The impact of using different costing methods on the results of an economic evaluation of cardiac care: microcosting vs gross-costing approaches. Health Econ 2009; : 377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]