Abstract

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is a very rare disease in which there is an abnormal, focal dilatation of the artery supplying the gallbladder. The condition may occur as a consequence of a localised inflammatory response, such as in cholecystitis. Here, we present the case of a 56-year-old man who presented with chronic cholecystitis in whom a 1.8 cm × 2 cm cystic artery pseudoaneurysm was found incidentally during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Prior to the operation, routine investigations such as ultrasound revealed no indication of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, ruptured or otherwise. This case is reported to emphasise that cystic artery pseudoaneurysm may be caused by chronic or acute cholecystitis and that skilled surgeons may handle them laparoscopically.

Keywords: Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, Cholecystitis, Laparoscopic

Case report

A 56-year-old Peruvian man who had lived in the UK for 21 years presented for an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to symptomatic gallstone disease. His past medical history was unremarkable apart from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, of which there was a family history. He was a non-smoker and reported only occasional alcohol intake. Preoperative abdominal ultrasound showed hepatic steatosis with no focal lesions and a thin-walled gallbladder containing numerous calculi (average size 3mm). Blood tests indicated raised gamma-glutamyl transferase, all other liver function tests, haemoglobin and clotting were normal. Preoperative echocardiography was not performed as there were no indications of infective endocarditis.

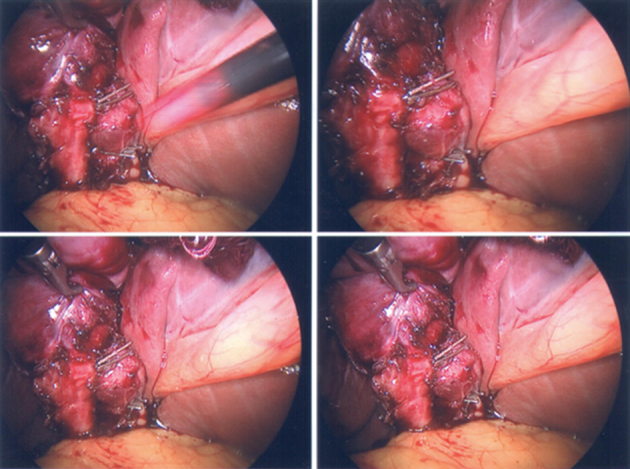

To remove the gallbladder, the traditional four-port approach to laparoscopic cholecystectomy was used. Pneumoperitoneum was achieved. After the initial dissection of Calot’s triangle, a large pseudoaneurysm in the distal portion of the anterior cystic artery (Fig 1) was identified. A large stone (2.5cm) was also found in Hartmann’s pouch and the gallbladder wall was thickened and oedematous, suggestive of chronic cholecystitis. The pseudoaneurysm appeared to measure 2cm × 1.8cm, which is large relative to others reported in the literature.1 Two titanium clips were applied proximal to the pseudoaneurysm, two distal to it and two distal to those, adjacent to the gallbladder. The artery was subsequently divided between the two pairs of distal clips and the pseudoaneurysm left in place. The posterior branch of the cystic artery was similarly clipped and divided. The cystic duct was clipped and divided in standard fashion.

Figure 1.

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm.

Diathermy and hydrodissection were used to dissect the gallbladder off the liver bed and the gallbladder was then removed through the umbilical port. A liver biopsy was also taken during the operation for assessment of the patient’s non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Owing to the unanticipated challenge of clipping the pseudoaneurysm of the anterior cystic artery, the operation was long, totalling 150 minutes.

The histological report substantiated a diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis and confirmed the absence of dysplasia or malignancy. The discrepancy between these results and those indicted by the ultrasound is probably a result of changes occurring in the intervening months between the ultrasound and the operation. The patient was allowed home the next day with simple analgesia. He has remained asymptomatic since the operation and has been able to get back to his normal life.

Discussion

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm occurring as a result of cholecystitis is a rare condition, despite the prevalence of cholecystitis. This may be because the inflammatory process occurring in and around the gallbladder results in thrombosis of the cystic artery at an early stage.2 To our knowledge, less than 30 cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm associated with cholecystitis have been reported in the literature, of which the majority have been cases of describing accounts of ruptured aneurysms.2,3 The propensity of cystic artery aneurysms to rupture renders the prospect of dealing with them laparoscopically unappealing to many.1,2 Indeed, it is likely that this case is the fourth to be handled laparoscopically and the first one to be done so without being identified prior to surgery by radiological investigations.1 This case report therefore adds to the growing body of literature that suggests that skilled surgeons may be able to handle these cases laparoscopically.1,3

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm has been reported to occur often as a post-surgical complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.3 Rupture of these pseudoaneurysms may lead to haemobilia, intraperitoneal bleeding and gastrointestinal haemorrhage which in turn may cause upper abdominal pain, jaundice, anaemia, melena and hematemesis.4 Owing to its rarity, it is likely that ruptured aneurysm of the anterior cystic artery is often overlooked as a cause of acute abdomen; however, it is clear that the severity of its consequences necessitate its inclusion into the list of possible differentials for this common presentation.

Machida et al. discuss the radiological investigation suitable for identifying cystic artery pseudoaneurysms and conclude that ultrasound, computed tomography and angiography can all be used.2 However, despite it being the most invasive diagnostic procedure, selective hepatic arteriography is considered the gold standard for cystic artery pseudoaneurysm diagnosis. Machida et al. go on to point out that ultrasound may not pick up small aneurysms or aneurysms that are obscured by the acoustic shadow of a large calculus. As the aneurysm described in the case above was not picked up during the patient’s abdominal ultrasound, despite being relatively large, it is possible that it was obscured by the acoustic shadow of the large gallstone found in Hartmann’s pouch. However, considering the size of the aneurysm described it is also possible that the sensitivity of ultrasound for picking up these arterial dilatations is fairly low.

Pseudoaneurysms are differentiated from true aneurysms by their occurrence in the background of an inflammatory process or trauma,3,5 which may damage the tunica media and externa allowing blood to collect between these two layers. Pseudoaneurysms may be caused by septic emoboli from infective endocarditis. However, the origin of the pseudoaneurysm in question is probably related to the confirmed presence of chronic cholecystitis, considering the lack of clinical indication for infective endocarditis. The pathophysiology of pseudoaneurysm in cases of either chronic or acute cholecystitis is unclear but probably associated with focal weakening of the tunica media and externa of the artery wall as a result of a local inflammatory response around the gallbladder.2,3 Furthermore, it has been suggested that the presence of large gallstones in the cystic duct may exert a direct pressure effect on the anterior cystic artery, which may further predispose to the formation of pseudoaneurysms.3 Considering this, it is possible that the large stone found in Hartmann’s pouch was a contributing factor to the formation of the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm in the case described above.

References

- 1.Alis D, Ferahman S, Demiryas S et al. Laparoscopic management of a very rare case: cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to acute cholecystitis. Case Rep Surg 2016; 2016: Article ID 1489013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machida H, Ueno E, Shiozawa S et al. Unruptured pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with acute calculous cholecystitis incidentally detected by computed tomography. Radiat Med 2008; (6): 384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loizides S, Ali A, Newton R et al. Laparoscopic management of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with calculus cholecystitis. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015; : 182–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda A, Kunou T, Saeki S et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with hemobilia treated by arterial embolization and elective cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2002; (6): 755–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anand U, Thakur SK, Kumar S et al. Idiopathic cystic artery aneurysm complicated with haemobilia. Ann Gastroenterol 2011; (2): 134–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]