Abstract

A 65-year-old man presented with a right supraclavicular neck mass and right arm pain. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a 96mm lesion in the upper thoracic paraspinal region extending into the deep supraclavicular fossa. The presentation was consistent with a sarcoma or lymphoma but fine needle aspiration was inconclusive. During open biopsy of the lesion, the patient had a rapid intraoperative haemorrhage of 1l from the tumour. Haemostasis could only be achieved by transarterial embolisation of the feeding vessel and the biopsy result confirmed Ewing’s sarcoma. Open biopsy is considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of certain tumour types; however, the morbidity from haemorrhage must be considered. This case highlights the key role that transarterial embolisation can play in achieving haemostasis in the neck.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Haemorrhage, Embolisation, Ewing’s, Neck mass

Neck masses are a common presentation in ear, nose and throat (ENT) clinics with a broad range of differential diagnoses including neoplasia, reactive lymphadenopathy, infection and developmental lesions. Approximately 55% of supraclavicular neck masses are malignant when evaluated by fine needle aspiration (FNA).1 Patient age is a key factor affecting the diagnosis, with rates of malignancy up to 68% in patients aged >40 years compared with 32% for those aged >40 years.1 Malignant supraclavicular neck masses are most likely to be metastatic lymph nodes from primary sites below the clavicles including the lung, breast, uterus, cervix and stomach.2 Lymphoma is the most common primary tumour identified in 7–10% of cases while sarcomas are uncommon and found in only 2% of neck masses.1,2

The head and neck is a highly vascular region, and haemorrhage is a common acute presentation in ENT. Interventional radiology plays a key role in managing refractory haemorrhage and is widely employed for vascular erosions from malignant tumours, refractory epistaxis and bleeding following tonsillectomy.3

Despite haemorrhage being a recognised risk of open biopsy, there is a paucity of published evidence on this topic. We describe an unusual case of major intraoperative haemorrhage from an open biopsy and its management.

Case history

A 65-year-old man presented with a 3-week history of a right-sided supraclavicular neck mass and right arm pain. He was a non-smoker with a past medical history of ischaemic heart disease and diabetes. On examination, he had a large firm mass in the supraclavicular fossa measuring approximately 10cm in diameter, no lymphadenopathy and no other significant abnormalities.

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed (Fig 1), and the differential diagnoses included a peripheral nerve sheath tumour or other sarcoma, primary soft tissue lymphoma and possibly a Pancoast tumour of the lung. The histology report from the initial FNA was inconclusive and the multidisciplinary team decision was to perform an open biopsy. During the biopsy, the lesion was easily accessed and had a thin fibrous capsule with a gel-like matrix. On incision of the matrix, there was rapid haemorrhage of 1l but no identifiable major vessels were involved. Haemostasis could only be achieved by packing the tumour site.

Figure 1.

Coronal T1 weighted post-contrast magnetic resonance imaging showing the enhancing mass extending from the right upper paraspinal region through the first intercostal space into the deep supraclavicular fossa

Following surgery, computed tomography (CT) angiography (Fig 2) was carried out as well as subsequent selective digital subtraction angiography (Fig 3) of the right dorsal scapula artery to confirm the arterial supply to the tumour. Transarterial embolisation was performed with a combination of 500μm microspheres and platinum microcoils (Fig 4), which achieved haemostasis and allowed removal of the packing material four days later. The patient was intubated on the intensive care unit for 20 days following the initial surgery owing to concerns of airway compromise both from haemorrhage and a haemostatic pack adjacent to the trachea. Histological examination of the biopsy specimen confirmed a Ewing’s sarcoma.

Figure 2.

Coronal multiplanar reformatted (maximum intensity projection) computed tomography angiography showing surgical packing material in the tumour cavity and the principal arterial inflow from the dorsal scapula artery

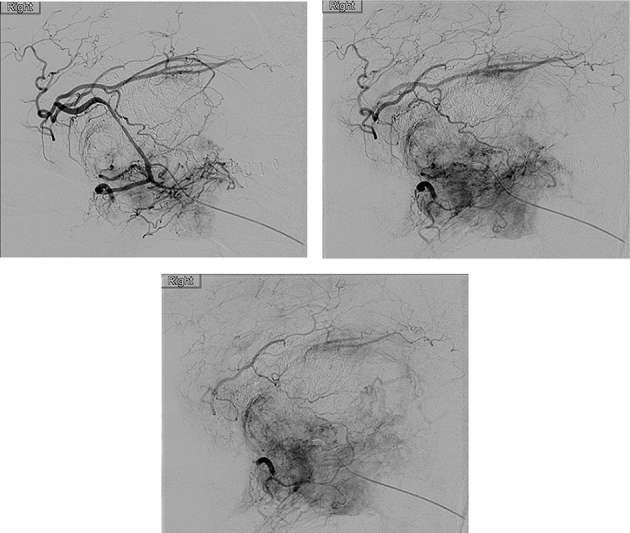

Figure 3.

Selective digital subtraction angiography of the dorsal scapula artery demonstrating the arterialisation of the tumour and enhancement of the hypervascular tumour parenchyma

Figure 4.

Fluoroscopy showing microcoils in the individual arterial branches on completion of embolisation

Discussion

Neck biopsy is an essential tool in the diagnosis of head and neck masses. Major haemorrhage from open biopsy in the head and neck is associated with specific tumour types including juvenile angiofibromas, paragangliomas and some thyroid malignancies.3 However, the incidence of clinically significant haemorrhage from open biopsy in any other type of lesion is poorly described in the literature.

Neck biopsies can be performed via three techniques (FNA, core biopsy and open biopsy), which yield incrementally larger tissue samples. The European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines recommend open biopsy as the gold standard approach in the diagnosis of lymphoma and either core or open biopsy in the diagnosis of sarcoma.4,5 This is because both tumour types require sufficient tissue for extensive immunohistochemistry staining to achieve an accurate diagnosis. Given the differential diagnosis of this lesion and inconclusive FNA, an open biopsy likely offered the best chance of a prompt definitive diagnosis, minimising any further delay to starting treatment.

The bleeding in our case was secondary to the unusual nature of the tumour and not due to an accidental vascular injury. As a result, it is not felt that core biopsy would have avoided this risk and significant haemorrhage would have been even more difficult to control in an outpatient setting. Significant haemorrhage and mortality from outpatient thyroid FNA and core biopsy has been reported previously.6 It is a particular concern in the neck owing to the risk of airway compromise.

The preoperative imaging in this case identified intratumoural vessels but showed no haemorrhagic foci or other features that would suggest major bleeding potential. Other preoperative imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance angiography would have been unlikely to predict the bleeding potential of this lesion. This case highlights that preoperative imaging is not a sensitive predictor of intraoperative bleeding risk and must be considered as part of the complete clinical picture. Digital subtraction angiography and embolisation has been described both preoperatively to mitigate bleeding risk and intraoperatively to control acute haemorrhage. However, these cases were specific head and neck tumour types including paragangliomas, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma and thyroid lesions.3 There is currently no described role for pre or intraoperative embolisation in suspected Ewing’s sarcoma.

The bleeding potential of all patients undergoing open neck biopsy should be considered carefully. Factors to bear in mind include tumour type, proximity or involvement of major vessels and use of anticoagulants where they cannot be withheld. Patients thought to be at high risk should be considered for preoperative embolisation while remembering that embolisation is not a risk free procedure. In addition, a preoperative ‘group and save’ sample is advised as well as surgery under general anaesthesia.

Conclusions

Open biopsy is an essential tool in diagnosing certain neck masses and while haemorrhage is a recognised complication, major haemorrhage is poorly described in the literature. This risk must be appreciated, especially when operating on tumours at the root of the neck or skull base region. Our report emphasises the essential role that digital subtraction angiography and embolisation played in achieving haemostasis in refractory haemorrhage from this lesion. This experience adds to the small body of literature on the potential complications of diagnosing sarcomas and may help further our understanding of the optimal management of these rare malignancies.

References

- 1.Ellison E, LaPuerta P, Martin SE. Supraclavicular masses: results of a series of 309 cases biopsied by fine needle aspiration. Head Neck 1999; : 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefebvre JL, Coche-Dequeant B, Van JT et al. Cervical lymph nodes from an unknown primary tumor in 190 patients. Am J Surg 1990; : 443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storck K, Kreiser K, Hauber J et al. Management and prevention of acute bleedings in the head and neck area with interventional radiology. Head Face Med 2016; : 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichenauer DA, Engert A, André M et al. Hodgkin’s lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(Suppl 3): iii70–iii75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(Suppl 3): iii102–iii112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kakiuchi Y, Idota N, Nakamura M, Ikegaya H. A fatal case of cervical hemorrhage after fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy of the thyroid gland. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2015; : 207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]