Abstract

Background

Zooprophylaxis is the use of wild or domestic animals, which are not the reservoir host of a given disease, to divert the blood-seeking malaria vectors from human hosts. In this paper, we systematically reviewed zooprophylaxis to assess its efficacy as a malaria control strategy and to evaluate the possible methods of its application.

Methods

The electronic databases, PubMed Central®, Web of Science, Science direct, and African Journals Online were searched using the key terms: “zooprophylaxis” or “cattle and malaria”, and reports published between January 1995 and March 2016 were considered. Thirty-four reports on zooprophylaxis were retained for the systematic review.

Results

It was determined that Anopheles arabiensis is an opportunistic feeder. It has a strong preference for cattle odour when compared to human odour, but feeds on both hosts. Its feeding behaviour depends on the available hosts, varying from endophilic and endophagic to exophilic and exophagic. There are three essential factors for zooprophylaxis to be effective in practice: a zoophilic and exophilic vector, habitat separation between human and host animal quarters, and augmenting zooprophylaxis with insecticide treatment of animals or co-intervention of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets and/or indoor residual spraying. Passive zooprophylaxis can be applied only in malaria vector control if cattle and human dwellings are separated in order to avoid the problem of zoopotentiation.

Conclusions

The outcomes of using zooprophylaxis as a malaria control strategy varied across locations. It is therefore advised to conduct a site-specific evaluation of its effectiveness in vector control before implementing zooprophylaxis as the behaviour of Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes varies across localities and circumstances.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40249-017-0366-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Malaria, Cattle, Mosquito, Vector control, Ethiopia

Multilingual abstract

Please see Additional file 1 for translations of the abstract into the six official working languages of the United Nations.

Introduction

Humans have known malaria for thousands of years. According to the World Malaria Report 2016 [1, 2], there were an estimated 212 million cases and 429,000 deaths due to malaria in 2015, approximately 88% of which were in the African region. Similarly, most of the deaths (90%) also occurred in the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region; of these approximately 74% were children under 5 years of age. The incidence and death of malaria, however, was reduced by 21% and 29%, respectively, in 2015 worldwide in comparison to the situation in 2010 [1, 2].

Africa is the most affected region due to a combination of factors including the presence of very efficient malaria vectors (Anopheles gambiae sensu lato and An. funestus) and the predominant parasite species Plasmodium falciparum, which is the species mostly responsible for severe malaria [2]. Weather conditions, which often allow transmission to occur year round, scarce resources, and socioeconomic instability, which has hindered efficient malaria control activities, have also led to a high malaria incidence in this region [1, 2].

Malaria parasites are one of the first pathogens to be studied in a public health context due to the high level of morbidity and mortality in humans. There are four known species of Plasmodium, which cause human malaria, with a fifth added to the list most recently from the forested regions of Southeast Asia. These are: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi [3, 4]. Plasmodium falciparum is the most virulent member of the group and it is responsible for the majority (99%) of malaria-related mortality [1, 3, 5]. The different Plasmodium species are host-specific though there have been periodic reports of simian malaria parasites being found in humans [4, 5].

The disease spreads from one person to another via the bite of a female mosquito of the genus Anopheles [5]. Anopheles mosquitoes belong to the order Diptera, family Culicidae, genus Anopheles, and series Pyretophorus. There are 465 to 474 described Anopheles species with 70 of its members recognized to transmit the Plasmodium parasite to humans [6]. Some of the species are species complexes because of the presence of morphologically indistinguishable sibling species within the complex [6]. For instance, the An. gambiae complex is a species complex composed of sibling species that are all difficult to identify morphologically using a taxonomic key but can be identified into its eight member species, namely An. arabiensis, An. gambiae, An. coluzzii, An. merus, An. melas, An. bwambae, An. quadriannulatus, and An. amharicus, using molecular techniques [7–9].

Anopheles arabiensis, the subject of this review, is mainly found in subtropical and tropical savannah regions on the African continent. Its population distribution ranges from the western coast of Africa above the equator, to farther north into the Sahel, to the southwestern corner of the Arabian Peninsula, Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, along the east coast, including Madagascar, and south into the desert and steppe environments of Namibia and Botswana in Southern Africa [6]. The adult An. arabiensis is well adapted to dry and forest sparse environments [10], whereas its immature stage prefers short-lived, sunlit, clear, and shallow aquatic breeding habitats mainly created by rainfall and human activities [11]. The density of larvae increases as the rainy season progresses. The abundance and development of the larvae is dependent on different physicochemical and biological factors [11], water turbidity and algae [12, 13], the presence of ammonium sulfate fertilizers [14], thermal limit [15], and the presence of maize pollen [16, 17].

In the eastern and southeastern African region where An. arabiensis remains the primary malaria vector, its population dynamics vary according to season, with its maximum population density recorded in the long rainy season from June to August [18]. It survives extreme dry seasons in the form of embryo dormancy in moist soil [19], continues reproduction using artificial breeding pans, and its population quickly builds up the following rainy season due to temporary breeding habitats being established [20].

The resting behaviour of An. arabiensis depends on whether its host resides indoors or outdoors. In areas where hosts mainly stay indoors, An. arabiensis exhibits an endophilic (indoor resting) behavioural pattern [21], whereas in areas where hosts are mainly outdoors, An. arabiensis exhibits both outdoor and indoor resting habits [22, 23]. The exophilic behaviour of An. arabiensis is also often observed following interventions such as the application of indoor residual spraying (IRS) and/or long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) [24, 25]. A shift from endophilic behaviour to exophilic behaviour is not only seen in An. arabiensis but in all other malaria vector species and it is attributed to the deterrence and/or contact irritancy due to indoor malaria vector control interventions (IRS and LLINs) [25–28].

The feeding and host preference behavior of An. arabiensis varies considerably from place to place. Evaluation of the human blood index (HBI) of An. arabiensis in Ethiopia and elsewhere in Africa showed both zoophagic and anthropophagic behaviour. Fornadel et al. [29] and Tirados et al. [30] documented highly anthropophilic behavioural patterns of populations of An. arabiensis from Zambia and Southern Ethiopia, respectively. Similar feeding patterns of preferring humans to other non-vertebrate hosts was observed in Senegal, in a blood meal analysis of populations of An. gambiae and An. arabiensis [31]. Exclusive zoophilic behaviour of An. arabiensis was reported in Madagascar [32], whereas most studies on populations of An. arabiensis from other countries documented an opportunistic feeding behaviour [33–37].

The time of host feeding varies depending on the host preference and on whether the host stays mainly indoors or outdoors. In an assessment of hourly person-biting rates of An. gambiae s.l. conducted in Miwani, Kenya, a region where An. gambiae (54%) and An. arabiensis (45%) exist in sympatry, the majority (83%) of female mosquitoes were found to be biting between 01:00 and 06:00, with a peak indoor biting at 06:00, while the peak outdoor activity occurred between 02:00 and 04:00 [38]. In Ahero village, where An. funestus comprised a large proportion of mosquitoes caught indoors (67.3%), the main indoor biting peak for An. arabiensis occurred at 03:00, while the outdoor biting activity peaked between 03:00 and 06:00. The same study concluded that An. arabiensis mosquitoes were 1.9 times more likely to bite indoors than outdoors, and that these mosquitoes had very low preference for human blood meals as compared to An. gambiae. Taye et al. [39] reported that An. arabiensis in Southern Ethiopia bites during the entire night with a peak between 23:00 and 03:00. A recent study by Yohannes and Boelee [40] conducted in Northern Ethiopia showed that An. arabiensis has more early biting activities, with 70% of the biting activity occurring before 22:00, with a peak between 19:00 and 20:00, which is similar to a study conducted by Kibret et al. [41] in Central Ethiopia.

A difference in the time of biting and rhythm seems to be affected by parity, with a larger proportion of possibly disease-transmitting parous mosquitoes being active in the later part of the night, mainly when humans sleep [39, 42]. Seasonality can also influence the biting activity of populations of An. arabiensis. Taye et al. [39] documented that the biting rate of An. arabiensis in August and April were 19.3 bites/person/night and 82 bites/person/night, respectively, which is a considerable difference.

Important malaria vectors are not uniformly distributed within a country with their range typically crossing national borders. The occurrence of Anopheles species varies according to macro- and micro-environmental differences exhibited by different bioecological areas. Therefore, entomological studies should incorporate a detailed distribution of the vector species, as it is the basis for risk assessment of malaria transmission [43, 44]. Thus, the abundance of anophelines is one entomological parameter used to describe the relationship between vectors and the incidence of malaria [45].

One of the keystones in malaria control strategy is tackling the vector, either by reducing the vector density or infectivity rate of the vector (i.e., the proportion of sporozoite positive mosquitoes compared to the total dissected mosquitoes), which will have an impact on malaria transmission and incidence. Based on previous research reports, it appears that the vector mosquito population of Ethiopia has developed resistance against most insecticides (dichloro- diethyl-trichloroethane, permethrin, deltamethrin, and malathion) [46]. The emergence and spread of insecticide resistance in some regions may suggest that other vector control tools may be needed to sustain control and mitigate the risk of malaria infection, despite the success of existing vector control intervention strategies, such as LLINs and IRS [46]. Consequently, new attention has been given to environmental management, biological control, and zooprophylaxis [47].

In malaria vector control, zooprophylaxis can be applied separately or in combination with other vector control tools. Application of zooprophylaxis is the use of wild or domestic animals, which are not the reservoir host of a given disease, to divert the blood-seeking malaria vectors away from the human host of that disease. Use of zooprophylaxis as a malaria vector control tool can be in an active, passive, or integrated form combined with chemical insecticides used in public health [47, 48].

Research assessing the effectiveness of zooprophylaxis has been done in various countries. In this paper, a qualitative systematic review using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was conducted with the aim of exploring the contribution of zooprophylaxis in the fight against malaria incidence and prevalence. Therefore, we explored entomological studies of which their outcomes either favorable or non-favorable in terms of application of zooprophylaxis. Meta-analysis was not possible due to the lack of common study outcomes in the retrieved articles.

Methods

Identification of papers and eligibility criteria

The databases PubMed Central®, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and African Journals Online were searched between December 2015 and March 2016. The published reports used in this review were retrieved from searches using the following key terms: “zooprophylaxis” or “cattle and malaria”, “malaria vector control”, and “host preference”. In cases where the key terms could not produce enough relevant information, references from related articles were copied and pasted in Google Scholar to get the full PDFs of the target articles. Review articles on zooprophylaxis were excluded from the synthesis but their content was assessed in order to weigh up their objective, their relevance and relatedness to our review, and their inclusiveness of contemporary information. Abstracts were selected if they were found to include information on zooprophylaxis, malaria control strategies, or on the behaviour of malaria vectors and their host preference. Irretrievable full text articles as well as non-English abstracts were excluded.

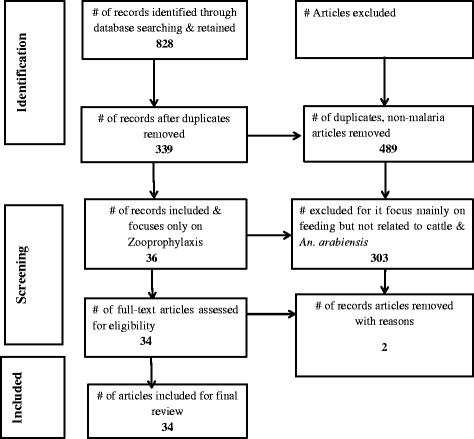

The selected articles were screened as follows: First, all abstracts not related to Anopheles biology, ecology, resting, feeding behaviour, feeding pattern, host preference, zooprophylaxis, or the diversion of mosquitoes to hosts other than humans were excluded. Second, duplicate and non-malaria related articles were also not considered. Bulletin news articles and articles reviewing the effects of zooprophylaxis discussed in other reviews were also excluded (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Systematic article selection

Data extraction from each article included author, date of publication, study location, mosquito species, study aim, study design, and study outcomes. Published research works reporting a significant association between the presence of livestock and reduced malaria infection were considered as supporting zooprophylaxis, and studies that either reported failure of zooprophylaxis or a poor association between zooprophylaxis and reduced malaria infection were considered as studies that disprove the effect of zooprophylaxis in malaria vector control.

Results

Study characteristics

Thirty-four articles were included in this review. Of these, 26 (76%) articles show that zooprophylaxis is either effective in malaria vector control, increases the incidence of malaria, or has no effect at all in malaria control. The methodologies of these articles (study aim, design, and sample size) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of methodological overview (study aim, design, and sample size) of 26 studies showing that zooprophylaxis either has a positive, negative, or no effect in malaria control

| Reference | Location | Study aim | Study design | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyimo et al., [58] | Kilombero, Tanzania | Evaluating the effectiveness of fungus bioinsecticide zooprophylaxis | Semi-field and small-scale field experimental study | 1690 and 547 An. arabiensis from the semi-field and field, respectively, were assessed for the development of fungal infection. |

| Kaburi et al., [53] | Kenya | Establishing effects of zooprophylaxis and LLINs | Cross-sectional survey | 80 households were surveyed; 4148 and 2615 vector mosquitoes were collected before and after the intervention, respectively, and blood sources were detected. |

| Bulterys et al., [49] | Zambia | Association between malaria infection and risk factors | Case-control study | 34 households with malaria history in the previous two years and 37 households without malaria history in the same time period were assessed for risk factors. |

| Fritz et al., [59] | Kenya | Effects of ivermectin and moxidectin on malaria vectors | Laboratory-based and field-based bioassays | Exact sample size not mentioned. |

| Muriu et al., [54] | Kenya | To determine the blood feeding pattern of Anopheles mosquitoes | Longitudinal study (mosquito collection and laboratory processing) | 3333 blood-fed Anopheles mosquitoes were collected from eight villages and blood sources were detected. |

| Mahande et al., [55] | Tanzania | Evaluation of feeding preference behavior | Field experimental study (mosquito collection and laboratory processing) | 3902 Anopheles mosquitoes were collected from the field and blood sources were detected; 506 Anopheles were trapped using odor based entry trap (OBET) and preference was detected. |

| Mahande et al., [83] | Tanzania | Assessing the effect of deltamethrin-treated cattle on An. arabiensis | Contact bioassay and experimental hut trials | 948 female An. arabiensis mosquitoes were used for contact bioassay. |

| Iwashita et al., [50] | Kenya | Assessing the added value of zooprophylaxis in the presence of ITNs | Cross-sectional survey (mosquito collection and laboratory processing, livestock survey, LLINs coverage and larval breeding habitat survey) | 1664 Anopheles mosquitoes were examined for blood meal source and vector infection rate. |

| Seyoum et al., [71] | Ethiopia | To assess the impact of livestock on the HBR and malaria transmission | Longitudinal study (mosquito collection and laboratory processing, parasitological and clinical survey, field experimental tukuls trial) | Mosquitoes were collected using HLC for 12 months (once/month/3 huts) and 1180 blood samples were collected from children under 10 years of age. |

| Habtewold et al., [52] | Ethiopia | A blood meal analysis to determine the host preference | Cross-sectional study (mosquito collection and laboratory processing) | 278 mosquitoes were tested for blood meal source and parasite positivity. |

| Rowland et al., [60] | Pakistan | The role of insecticide-treated livestock (dipping method) in the control of malaria | Field experimental study (Randomized controlled trial) | 842 Anopheles mosquitoes were monitored; an average 4112 blood samples were collected and tested for parasite detection over a three-year period. |

| Foley et al., [61] | Indonesia | The effect of ivermectin-treated animals and humans on An. farauti mortality | Experimental study and modeling | Exact sample size not reported. |

| Hewitt and Rowland, [62] | Pakistan | The treatment of cattle with pyrethroids to control zoophilic mosquitoes | Field experimental study | 38,815 anopheline mosquitoes were collected over a two-year period. |

| Temu et al., [64] | Mozambique | Identifying risk factors for malaria infection | Cross-sectional survey | 8338 children under 15 years of age were screened for malaria detection. |

| Tirados et al., [70] | Ethiopia | Attraction of mosquitoes to humans in the absence and presence of cattle ring; mosquito host preference using animal and human baited traps | Field experimental study | Exact sample size not mentioned. |

| Yamamoto et al., [51] | Burkina Faso | The use and effects of different mosquito control measures | Case-control study | 117 cases and 221 control study subjects were screened for parasites. |

| Githinji et al., [67] | Kenya | Interactions between humans and their micro-ecological environment | Case-control study | 342 case and 328 control individuals were assessed for risk factors associated with malaria. |

| Deressa et al., [68] | Ethiopia | Household and socioeconomic factors associated with childhood febrile illness | Cross-sectional survey | 2372 households were investigated for risk factors associated with malaria. |

| Tirados et al., [30] | Ethiopia | Feeding and resting preference to evaluate the protective value of cattle against An. arabiensis | Laboratory-based (ELISA) and Field experimental study, Longitudinal study (mosquito collection) | 45,527 An. arabiensis, 4218 An. pharoensis, and 13,241 An. funestus group were collected |

| Palsson et al., [65] | Guinea Bissau | Environmental risk factors associated with increased malaria risk and vector abundance | Longitudinal study (mosquito collection) | 9873 Anopheles mosquitoes were collected over a three-year period. |

| Habtewold et al., [63] | Ethiopia | Deltamethrin-treated zebu and possible behavioral avoidance of An. arabiensis | Contact bioassay and Field experimental study | 1102 Anopheles mosquitoes were monitored for feeding success; 366 Anopheles mosquitoes were tested for blood meal source. |

| Bøgh et al., [57] | The Gambia | Effect of passive zooprophylaxis on malaria transmission | Paired cohort study of 102 children under age 7 | A total of 204 children were monitored for malaria in the presence and absence of cattle. |

| Idrees and Jan, [81] | Pakistan | To determine the role of cattle ownership on the prevalence of malaria | cross-sectional survey | 1873 blood samples were collected and tested for malaria. |

| Ghebreyesus et al., [69] | Ethiopia | Household risk factors associated with malaria incidence | Cross-sectional survey | 2114 children under 10 were screened for malaria and associated risk factors. |

| Bouma and Rowland, [66] | Pakistan | Parasite prevalence in children housing with or without cattle | Cross-sectional survey | 2042 blood samples were collected from school children aged 2–15. |

| Mayagaya et al., [82] | Tanzania | To investigate the impact livestock ownership has on vector ecology and malaria parasite infectivity rate | Longitudinal study (mosquito collection) | 29,393 Anopheles mosquitoes were collected over a three-year period. |

Thirteen (38%) articles show that zooprophylaxis is effective in malaria vector control. Of these, three research works were conducted in Asia (1 from Indonesia, and 2 from Pakistan), and the remaining ten were reported from Africa (nine from east Africa and one from southern Africa). Regarding the study design, there was one case-control, one laboratory-based and field-based bioassays, one contact bioassay and field experimental hut trial, one human landing catch (HLC) and parasitological survey, one randomized controlled trial, one cross-sectional, and seven experimental studies (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Summary of 26 studies showing outcome parameters and whether zooprophylaxis is effective or not in malaria control

| Reference | Mosquito species | Outcome parameter | Percent protection | Conclusion (yes/no to zooprophylaxis; that is, is it effective or not?) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyimo et al., [58] | An. arabiensis | Mosquito mortality, fecundity | 90% of mosquitoes fed on fungus-treated cattle become infected immediately and 70% of the infections occurred after three days. | Yes (if cattle treated with bioinsecticide) |

| Kaburi et al., [53] | An. gambiae complex, An. funestus | Man biting rate, HBI, CSP | MBR ratio decreased significantly, with RC of (−0.96; SE = 0.834; P = 0.017). HBI decreased significantly with RC of (0.239; SE = 0.039; P = 0.015 [P < 0.05]), especially in households with >4 cattle. | Yes (if cattle and LLINs co-applied) |

| Bulterys et al., [49] | An. arabiensis, An. funestus | Parasite prevalence | The risk of P. falciparum infection (aOR = 0.13; 95%CI = 0.03–0.56) was reduced. | Yes (if cattle sheds are separated from human quarters) |

| Fritz et al., [59] | An. gambiae s.s., An. arabiensis | Mosquito density, HBI | 90% mortality of mosquitoes were fed on ivermectin-treated cattle. | Yes (if cattle treated with systemic insecticide) |

| Muriu et al., [54] | An. arabiensis, An. pharoensis, An. funestus | HBI, bovine blood index | 71.8% indoor and 41.3% outdoor collected mosquitoes, respectively, were fed on bovine. | Yes |

| Mahande et al., [55] | An. arabiensis, An. gambiae | Mosquito density, HBI | 90.3% of mosquitoes were trapped by cattle odor and 9.7% of mosquitoes were trapped by human odor (P = 0.005). A lower HBI was recorded in both the outdoor (0.1–0.3) and indoor (0.4–0.9) collected mosquitoes. | Yes (if cattle kept in human surroundings) |

| Mahande et al., [83] | An. arabiensis | Mosquito mortality, HBI, | 50% of mosquitoes fed on treated cattle were knock downed 21 days after treatment. Treated cows caused higher mortality (mean = 2) as compared to untreated cows (m = 0.3). |

Yes (if cattle is treated with deltamethrin every three weeks) |

| Iwashita et al., [50] | An. arabiensis, An. gambiae s.s, An. funestus s.s | Mosquito density, CSP rate | 40.5% (CI: 36.9–44.2) of An. arabiensis fed on cattle, 12.0% (CI: 9.7–14.6) of An. arabiensis fed on humans; ITNs and cattle associated with decreased CSP. | Yes (if cattle co-applied with ITNs) |

| Seyoum et al., [71] | An. arabiensis, An. pharoensis | HBR, parasite prevalence | HBRs of An. arabiensis in mixed and separate cattle and without cattle were 8.45, 4.64, and 5.97, respectively. Similarly, mean parasitemia were 26.7%, 15.0%, and 23.85%, respectively. | Yes (if cattle is separated from human dwelling) |

| Habtewold et al., [52] | An. arabiensis, An. quadriannulatus | Mosquito density, HBI | A significantly higher proportion of mosquitoes was fed on livestock in site C compared to site A (χ 2 = 44.1, Df = 1, P < 0.001) or B (χ 2 = 25.9, Df = 1, P < 0001). | Yes (in certain areas) |

| Rowland et al., [60] | An. stephensi, An. culicifacies | Mosquito mortality, parasite prevalence | 56% reduction in P. falciparum malaria; 31% reduction in P. vivax malaria | Yes (if cattle treated with insecticides) |

| Foley et al., [61] | An. farauti | Mosquito mortality | 80–100% mortality observed in mosquitoes fed on treated cattle in the first three days after treatment. | Yes (if cattle treated with insecticides) |

| Hewitt and Rowland, [62] | An. stephensi, An. culicifacies | Mosquito mortality | 50% reduction in longest vector survivors | Yes (if cattle treated with insecticides) |

| Temu et al., [64] | An. gambiae complex, An. funestus | Malaria incidence | Increased risk of malaria incidence (OR = 3.2; 95%CI: 2.1–4.9) | No |

| Tirados et al., [70] | An. arabiensis, An. pharoensis | Mosquito density, | There was no significant difference in mean An. arabiensis density (means = 24.8 and 37.2 mosquitoes/night, respectively; n = 12, P > 0.22) caught outdoors by HLC with or without a ring of cattle. The catch of An. arabiensis in human-baited traps (HBT) was 25 times greater than in cattle-baited traps (CBT) (34.0 vs. 1.3, n = 24; P < 0.001) whereas, for An. pharoensis there was no significant difference. | No |

| Bouma and Rowland, [66] | – | Parasitemia | Malaria prevalence (15.2%) was significantly greater among children of families which kept cattle than among those which did not (9.5%) | No |

| Yamamoto et al., [51] | An. gambiae s.l., An. funestus | Mosquito density, parasite prevalence | Positive correlation between donkeys and An. gambiae indoors (Pearson’s r = 0.21, P = 0.0002) | No |

| Githinji et al., [67] | An. gambiae s.l. | Parasitemia | 53% increased risk of acquiring malaria if oxen kept in the house | No |

| Deressa et al., [68] | – | Parasitemia | Sharing house with livestock increases the risk of malaria (OR = 1.3, 95%CI: 1.1–1.6) | No |

| Tirados et al., [30] | An. arabiensis, An. pharoensis | Mosquito density, HBI, CSP | The HBIs for outdoor and indoor mosquitoes were 51% and 66%, respectively. CSP for P. falciparum and P. vivax were 0.3% and 0.5%, respectively. Five times more mosquitoes inside human baited trap. | No |

| Idrees and Jan, [81] | Parasitemia | Higher malaria burden was documented among children of families which kept cattle (11.20%) than among those which did not keep it (7.10%) | No | |

| Ghebreyesus et al., [69] | – | Parasitemia | Sleeping with animals in the house was significantly associated with risk of malaria (RR = 1.92, 95%CI: 1.29–2.85) | No |

| Palsson et al., [65] | An. gambiae Culex Aedus | Mosquito density | Presence of pigs in a house was associated with increased mosquito abundance in the bedrooms of the same house. | No |

| Bøgh et al., [57] | An. gambiae, An. arabiensis, An. melas | Parasitemia | No significant differences in either the risk of parasitaemia (OR = 1.69, P = 0.26) or in high-density parasitaemia (OR = 0.73, P = 0.54). | Either (No significant differences in either the risk of parasitaemia) |

| Habtewold et al., [63] | An. arabiensis, An. pharoensis, An. tenebrosus | Mosquito mortality | Deltamethrin applied to Zebu cattle was able to provoke up to 50% mortality in mosquitoes for the 1st four consecutive weeks and then its efficacy declined after wards. | Either (reduction in density was not significant) |

| Mayagaya et al., [82] | An. gambiae s.l. An. funestus s.l. | Mosquito density CSP, HBI |

No significance difference in mean mosquito density in households with and without livestock. Lower sporozoite rate was observed in houses with livestock however, other compounding factors should be accounted | Either |

CSP circumsporozoite test

Another thirteen (38%) studies show that zooprophylaxis either increases the incidence of malaria or has no effect at all on malaria transmission. Of these, two research works were conducted in Asia (Pakistan), and the remaining 11 were reported from Africa (three from western Africa and eight from eastern Africa). Regarding the study design, there were three field experimental studies, one paired cohort study, two case-control studies, two longitudinal studies and the rest five were cross-sectional surveys (see Tables 1 and 2).

Eight (24%) articles are modelling studies that report the role of zooprophylaxis in malaria vector control (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of eight modeling studies that report on zooprophylaxis as a malaria vector control tool

| Authors | Data source | Species | Study aim | Study design | Recommendations on the use of zooprophylaxis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Franco et al., [75] | Pakistan and Ethiopia | An. stephensi, An. arabiensis | To model the role of livestock in malaria control | Mathematical model | Livestock could have zooprophylactic effect with certain conditions such as maximum density of vector population prior to introduction, and sufficiently high number of livestock. Treatment of livestock with non-repellent insecticides and increasing the attractiveness of livestock with attractants will maximize efficacy. |

| Levens, [77] | Multiple sources | An. arabiensis | To model the role of insecticide zooprophylaxis, LLINs | Mathematical model | More than 80% coverage of LLINs to community and 80% coverage of insecticide treatment to livestock are important to achieve global reduction and elimination of the disease. |

| Nah et al., [76] | South Korea and others | An. sinensis | To investigate the effect of zooprophylaxis | Mathematical model | Decrease of animal population increases the basic reproduction number R0. Passive zooprophylaxis is an effective malaria control strategy in South Korea. |

| Hassanali et al., [72] | n/a | n/a | Relationship between hosts, mosquito habitat, and the relative number of individuals in the group | Computer simulation model | When the distance between human and animal host increases, the number of bites/person first decreases and is followed by an increase in the number of bites. Animals should not be placed very close to humans because it could lead zoopotnentiation and at the same animals should not be placed very far from humans otherwise they lose their protective efficacy. |

| Killeen and Smith, [78] | n/a | An. arabiensis, An. gambiae | To predict the effect of mass coverage of LLINs on users and non-users | Computer simulation model | With mass coverage of LLINs and IRS capable of excito-repellency in the presence of cattle, it is possible to protect both the users and non-users of ITNs. |

| Kawaguchi et al., [73] | n/a | n/a | Combining zooprophylaxis and IRS | Computer Simulation model | Habitat separation of cattle and humans is important for the success of zooprophylaxis. When blood host density is below the blood feeding satiation level, zooprophylaxis will fail. Spraying insecticides in human dwellings diverts mosquitoes to other hosts. |

| Saul, [74] | n/a | n/a | Examining the effects of animals on the transmission of vector-borne diseases | Computer simulation model | Feeding on animals decreases transmission to humans but increases mosquito survival rate. Keeping animals and humans away from breeding sites is a practical control measure. Insecticide zooprophylaxis may reduce vectorial capacity. |

| Killeen et al., [84] | n/a | An. funestus, An. gambiae An. arabiensis | The influence of host availability on vector blood meal choice | Computer simulation model | Increased cattle populations would cause a significant reduction in malaria in the Gambia due to a high An. arabiensis population, compared to no significant influence in Tanzania. |

n/a not applicable

Outcome parameters measured

Ten studies measure parasitaemia and/or vector abundance. Eleven studies measure mosquito abundance, HBI, and/or the sporozoite rate. Four studies measure mosquito mortality and knockdown. Two studies measure mosquito biting behaviour and human landing catch. Finally, one study uses physiological status and mosquito mortality as a response variable (see Tables 1 and 2).

The role of zooprophylaxis in malaria control

The role of domestic animals, particularly cattle, in reducing malaria incidence differs with the zooprophylaxis type, which can be categorized as passive, active, combination, or insecticide zooprophylaxis.

Passive zooprophylaxis is the natural prophylactic effect of cattle that is seen when cattle density within a community is increased. Its effect can be studied by evaluating the association between domestic animal ownership and parasitaemia [49–51], or mosquito blood meal source, mosquito infectivity [30, 50, 52, 53] or mosquito density [35, 54, 55].

Active zooprophylaxis refers to the deliberate introduction of domestic animals in order to divert mosquitoes away from human settlements towards other non-transmitting hosts. Active zooprophylaxis is studied by evaluating the association between malaria prevalence and cattle ownership using paired cohort studies of people living with cattle placed at close proximity and people living with cattle placed at a distance [56, 57].

Combination zooprophylaxis refers to the use of insecticide treated nets (ITNs) and IRS being integrated with livestock placed in a separate shed in order to induce a push-pull effect, thereby aiming to reduce the risk of disease incidence. The deliberate introduction of LLINs and IRS is used as the pushing factor, whereas domestic animals placed strategically is used as the pulling factor. Zoophilic and opportunistic mosquitoes such as An. arabiensis are attracted by domestic animals, particularly cattle (i.e. pulling effect), and the chemicals used in the impregnation of bed nets and IRS are capable of inducing repellence of the vector before it comes into contact with the human host. The effect is studied by evaluating the association between ITN ownership, IRS coverage, livestock ownership, and malaria prevalence [50, 53].

Insecticide zooprophylaxis is the treatment of cattle by sponging or dipping the cattle with insecticides in order to pass on a lethal dose of insecticides to the blood-feeding mosquitoes. This effect can be studied by evaluating the difference in mosquito mortality and density, and malaria incidence in households with both treated and untreated domestic animals [56, 58–63].

The studies examined in this scoping review found that zooprophylaxis can have a positive, negative, or no effect in malaria vector control. In terms of the negative effect, pig and donkey keeping was reported to be a risk factor for malaria transmission in Mozambique [64], Guinea Bissau [65], and Burkina Faso [51]. Similarly, Bouma and Rowland [66] noticed an increased Plasmodium prevalence in children in Pakistan living in households with cattle, and Githinji et al. [67] concluded that the presence of cattle and long grass in homesteads results in a 1.81 higher risk for malaria infection in Kenya. Similarly, in studying the risk factors associated with malaria incidence, it was concluded that humans sleeping in the house with animals have a significantly higher risk of contracting malaria in Ethiopia [68, 69].

Several research outputs on the other hand, either lack strong conclusion with reference to the role of zooprophylaxis or the reduction in the risk of malaria infection has been attributed to other confounding factors. For instance, research conducted in the Gambia by Bøgh et al. [56, 57] suggested reduced HBI and CSP rate for mosquitoes collected from households living with cattle as compared to those mosquitoes from households without cattle. However, there was no significant difference between the groups in the HBI and CSP rates neither of An. gambiae s.l. nor in the estimated malaria transmission risk. Furthermore, the decrease in parasitaemia, in households living with cattle could be attributed to the fact that cattle owners were wealthier than non-cattle owners were, therefore less risk of malaria infection could be associated with improved life standard of cattle owners.

Tirados et al. [30] conducted an entomological study on An. arabiensis and An. pharoensis mosquitoes in Arba Minch, Southwestern Ethiopia in order to determine the host preference, resting behaviour of the vector population, and protective value of cattle against malaria. They concluded that cattle have a protective value against An. pharoensis (secondary vector) both indoors and outdoors. An. arabiensis (major vector) mosquitoes from this area, however, remain anthropophagic, exophagic, and exophilic, and can sufficiently feed on humans to transmit the disease. Therefore, humans staying indoors are only mildly protected if cattle are outdoors. Habtewold et al. [63] also assessed the effectiveness of deltamethrin-treated zebu and the related behavioural avoidance of An. arabiensis in the same region, and concluded that cattle have a protective value against An. pharoensis. However, no zooprophylactic effect was observed by placing zebu cattle near humans for An. arabiensis.

A number of reports and modelling studies argue that zooprophylaxis is effective under specific circumstances. According to Tirados et al. [70], zooprophylaxis is only effective for An. arabiensis when humans are indoors and cattle are outdoors. The human biting rate (HBR) was reported to be highest in mixed dwellings and lowest when cattle are kept separately both in Ethiopia [71] and Zambia [49]. This is also supported by modelling studies conduced by Hassanali et al. [72], Kawaguchi et al. [73], and Saul [74], who argue that separating the habitats of cattle and humans is necessary for the success of zooprophylaxis. This is due to the fact that the presence of cattle may decrease malaria transmission to humans but increase the mosquito survival rate. In addition to habitat separation, the animal population should increase above a threshold value, which results in the diversion of mosquitoes being a more effective malaria control strategy than decreasing the mosquito population [75, 76].

Reports confirming the effectiveness of zooprophylaxis are from African and Asian countries. Six studies are field experiments on insecticide zooprophylaxis. Regarding the successfully used treatments on cattle, these include fungus (bioinsecticide zooprophylaxis) [58], ivermectin [59, 61], deltamethrin [55, 60, 62], permethrin, and lambda cyhalothrin [62]. It was found that fungal, ivermectin, and deltamethrin-treated animals significantly reduce survival rates of malaria vectors, as well as fecundity. Residual effects are longest in deltamethrin-treated cattle. Studies on passive zooprophylaxis are mainly population-based case control studies and surveys. In these studies, different household risks for the transmission of malaria were evaluated. The combination effect of ITNs, IRS, and livestock was also assessed [50, 53, 73, 77, 78].

Deressa et al. [68], Kaburi et al. [53], and Iwashita et al. [50] collected mosquitoes from households, made inventories of livestock, and assessed the presence or absence of LLINs in Kenyan households. They found that both the person-biting rate and the HBI of An. arabiensis decrease with an increase in the number of cattle in households with LLINs, demonstrating the additive role of LLINs in zooprophylaxis. This is also supported by modeling studies conducted by Levens [77], and Killeen and Smith [78], who argue that scaling up mass coverage of LLINs to 80% in the community and ensuring a 80% coverage of livestock treatment with pyrethroids could lead to a global reduction and elimination of the disease.

The separation of human shelters and animal sheds at a certain distance [50–57, 66, 69] can be combined with the use of LLINs and IRS [50, 53], and the treatment of domestic animals with appropriate insecticides [55, 58–63]. The type of mosquito species and its feeding and resting behavior affect the efficacy of zooprophylaxis. Thus, ownership of domestic animals in the presence of anthropophilic vectors such as An. gambiae and An. funestus may lead to an increased risk of malaria incidence. In contrast, ownership of domestic animals may lead to a lower risk of malaria incidence in areas where zoophilic and/or opportunistic vector species such as An. arabiensis and An. pharoensis predominate [30, 50, 57, 63].

Discussion

Malaria remains a major public health burden in Sub-Saharan Africa and continually finding effective control strategies is of great importance. For zooprophylaxis to be an effective control strategy, several conditions are required. A zoophilic and exophilic vector is the most essential component for zooprophylaxis to be effective. Habitat separation between human and host animal quarters is the second most important condition. Third, zooprophylaxis can be augmented through insecticide treatment of the animal and co-intervention with LLINs and/or IRS.

The main vectors identified that can successfully be controlled with zooprophylaxis were An. arabiensis and An. pharoensis in Africa [49, 52, 53, 55, 70, 71], and An. stephensi, An. culicifacies, An. sinensis, and An. farauti in Asia [60–62, 76].

Anopheles arabiensis is one of the main vectors of malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is known mostly for zoophilic [32, 36, 52, 53, 55], opportunistic [35, 79], and occasionally anthropophilic behaviour [29, 30, 80]. Thus, the behaviour of An. arabiensis can be varied depending on the location of the host (indoor versus outdoor) and local genotype of vector population, with the West African population mostly identified as anthropophilic and the eastern counterpart being more zoophilic [30, 56]. It may therefore be concluded that An. arabiensis is an opportunistic feeder, feeding on both human and cattle depending on host availability. This is the basis of a line of thought that zooprophylaxis can be introduced to control malaria where An. arabiensis is the main malaria vector.

Separation of human living quarters and livestock quarters was found to be another key precondition in the process of implementing zooprophylaxis. In almost all instances where people and livestock shared the same house, people ended up at a higher risk of malaria infection [51, 64–67]. Thus, the presence of cattle may reduce the HBR as well as the HBI, but this is no guarantee for decreasing the estimated transmission risk or having a significant prophylactic effect. The fact that cattle may play a role as an attractant for vectors to human resting places has been proven in several reports [51, 64–70, 81, 82].

In addition to the presence of zoophilic vectors and the separation of humans and cattle, zooprophylaxis can be further strengthened if augmented with other interventions. This may include treatment of livestock with insecticides, with the primary purpose of killing mosquitoes that feed on the animal. Several reports show the success of this, including with using fungus formulations (bioinsecticide zooprophylaxis) [58], ivermectin [59, 61], deltamethrin, [60, 62, 83], permethrin, and lambda cyhalothrin [62]. In all instances, insecticide-treated animals significantly reduced survival rates of malaria vectors, as well as fecundity. Residual effects were longest in deltamethrin-treated cattle. Furthermore, a lower risk of malaria was reported when zooprophylaxis and other mainstay vector tools (LLINs and IRS) were used in combination [50, 53, 73, 77, 78].

As a negative side effect, the presence of cattle leads to a higher survival rate of An. arabiensis due to the abundance of available blood meals, increasing the mosquito population. This phenomenon of zoopotentiation calls for the need to evaluate zooprophylaxis as a control strategy thoroughly before introducing it into a community. Zoopotentiation may not only occur through an increase in blood meals and host availability, but also through cattle puddles, which provide an ideal breeding site for the development of mosquito larvae, hence increasing the mosquito population [74, 84].

Another point of caution is the fact that when mosquito abundance is enlarged, other vector-borne diseases may also increase in incidence. Both passive and active zooprophylaxis only divert mosquitoes to different hosts but cause no decrease in vector abundance. The advantage of insecticide zooprophylaxis is its ability to reduce the survival and fecundity of mosquitoes. However, this is not necessarily beneficial. A decrease in the number of zoophilic vectors may give rise to an increase of a different and possibly more anthropophilic vectors indirectly via decreased competition for larval space and resources. The result would be that insecticide zooprophylaxis would only reduce malaria transmission temporarily. Thus, further research on the possible consequences of the use of insecticide zooprophylaxis is required to make a more accurate evaluation. This review had certain limitations. A more objective selection of reports could be made by letting a number of people independently select or exclude certain reports. This could result in a more detailed description of the different methods used in experiments on zooprophylaxis.

Conclusions

Zooprophylaxis should be evaluated using a site-specific approach, as in some areas it is effective whereas in others it is not. The effectiveness depends on several factors including distance from human dwelling to the breeding site of mosquitoes and the use of other control strategies such as LLINs and IRS. These factors influence the resting behaviour of local malaria vectors. Moreover, the zoophilic behaviour of An. arabiensis varies in different African countries, showing a more anthropophilic behaviour in West Africa as compared to countries more to the east of the continent. This suggests that zooprophylaxis could be more effective in some East African countries, where the species are zoophilic. The use of other malaria control strategies may have also influenced the evaluated results of experiments on zooprophylaxis. Future studies, such those on an estimation of the distance threshold between human quarters and livestock pens, and the additive effect of repellents on zooprophylaxis, could further strengthen the value of zooprophylaxis in malaria vector control.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Jimma University VLIR-IUC program for logistical support.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Jimma University VLIR-IUC program.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets were generated or analysed during this scoping review.

Abbreviations

- HBI

Human blood index

- HBR

Human biting rate

- IRS

Indoor residual spray

- ITN

Insecticide treated net

- LLIN

Long-lasting insecticide-treated net

- OBET

Odour based entry trap

- WHO

World Health Organization

Additional file

Multilingual abstract in the six official working languages of the United Nations. (PDF 609 kb)

Authors’ contributions

AA, GH, and DY were involved in the framing of the study and the drafting of the paper. BD was involved in the electronic data search. LD and DY critically commented on the paper. All authors read and approved the final version.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40249-017-0366-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Abebe Asale, Email: abebea663@gmail.com.

Luc Duchateau, Email: Luc.Duchateau@UGent.be.

Brecht Devleesschauwer, Email: Brecht.Devleeschauwer@ugent.be.

Gerdien Huisman, Email: Gerhardina.Huisman@ugent.be.

Delenasaw Yewhalaw, Email: delenasawye@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World health report 2016. 2016; http://who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2016/report/en/. Accessed 11 Apr 2017.

- 2.World Health Organization. World health report 2015. 2015; http://who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2015/report/en/. Accessed 24 Dec 2015.

- 3.Cox FEG. History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasite Vectors. 2010;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox-Singh J. Zoonotic malaria: Plasmodium knowlesi, an emerging pathogen. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:530–536. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283558780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rich SM, Xu G. Resolving the phylogeny of malaria parasites. Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12973–12974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110141108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Mangiun S, Rubio-Palis Y, Chareoviriyaphap T, Coetzee M, et al. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasite Vectors. 2012;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae Complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;4(4):520–529. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krzywinski J, Besansky NJ. Molecular Systematics of Anopheles: from subgenera to subpopulations. Annu Rev Entomol. 2003;48:111–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sallum MAM, Schultz TR, Foster PG, Aronstein K, Wirtz RA, Wilkerson RC. Phylogeny of Anophelinae (Diptera: Culicidae) based on nuclear ribosomal and mitochondrial DNA sequences. Sys Entomol. 2002;27:361–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3113.2002.00182.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Afrane YA, Lawson BW, Githeko AK, Yan G. Effects of microclimatic changes caused by land use and land cover on duration of gonotrophic cycles of An. gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) in western Kenya highlands. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:974–980. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/42.6.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mereta TS, Yewhalaw D, Boets P, Ahmed A, Duchateau L, Speybroeck N, et al. Physico-chemical and biological characterization of anopheline mosquito larval habitats (Diptera: Culicidae): implications for malaria control. Parasite Vectors. 2013;6:320. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gimnig JE, Ombok M, Kamau L, Hawley WA. Characteristics of larval anopheline (Diptera: Culicidae) habitats in western Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:282–288. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuna N, Githeko AK, Nakayama T, Minakawa N, Takagi M, Yan GY. The association between the phytoplankton, Rhopalosolen species (Chlorophyta; Chlorophyceae), and Anopheles gambiae Sensu Lato (Diptera: Culicidae) larval abundance in western Kenya. Ecol Res. 2006;21:476–482. doi: 10.1007/s11284-005-0131-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutero CM, Ng'ang'a PN, Wekoyela P, Githure J, Konradsen F. Ammonium sulphate fertilizer increases larval populations of Anopheles arabiensis and culicine mosquitoes in rice fields. Acta Trop. 2004;89:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyons CL, Coetzee M, Terblanche JS, Chown SL. Thermal limits of wild and laboratory strains of two African malaria vector species, Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus. Malar J. 2012;11:226. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye-Ebiyo Y, Pollack RJ, Spielman A. Enhanced development in nature of larval Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes feeding on maize pollen. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:90–93. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye-Ebiyo Y, Pollack RJ, Kiszewski A, Spielman A. Enhancement of development of larval Anopheles arabiensis by proximity to flowering maize in turbid water and when crowded. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:748–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amel AH, Abd el Hamid DN, David EA, Haider AG, Abdel-Musin AA, Gwiria MS, Theander TG, Alison MC, Hamza AB, Dia-Eldin AE. A marked seasonality of malaria transmission in two rural sites in eastern Sudan. Acta Trop. 2002;83:71–82. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(02)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minakawa N, Githure JI, Beier JC, Yan G. Anopheline mosquito survival strategies during the dry period in western Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:388–392. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenraadt CJM, Githeko AK, Takken W. The effects of rainfall and evapotranspiration on the temporal dynamics of Anopheles gambiae s.S. And Anopheles arabiensis in a Kenyan village. Acta Trop. 2004;90:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mnzava AE, Rwegoshora RT, Wilkes TJ, Tanner M, Curtis CF. Anopheles arabiensis and An. gambiae chromosomal inversion polymorphism, feeding and resting behavior in relation to insecticide house spraying in Tanzania. J Med Vet Entomol. 1995;9:316–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1995.tb00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faye O, Konate L, Mouchet J, Fontenille D, Sy N, Hebrard G, et al. Indoor resting by outdoor biting females of Anopheles gambiae Complex (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Sahel of northern Senegal. J Med Vet Entomol. 1997;34:285–289. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coluzzi M, Sabatini A, Petrarca V, Di Deco M. Chromosomal differentiation and adaptation to human environments in the Anopheles gambiae Complex. Trans Roy Soc TropMed Hyg. 1979;73:483–497. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell TL, Govella NJ, Azizi S, Drakeley CJ, Kachur SP, Killeen GF. Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2011;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padonou GG, Gbedjissi G, Yadouleton A, Azondekon R, Razack O, Oussou O. Eet al. Decreased proportions of indoor feeding and endophily in Anopheles gambiae s.l. populations following the indoor residual spraying and insecticide-treated net interventions in Benin (West Africa) Parasite Vectors. 2012;5:262–272. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy MR, Overgaard HJ, Abaga S, Reddy VP, Caccone A, Kiszewski AE, et al. Outdoor host seeking behavior of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes following initiation of malaria vector control on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2011;10:184. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pates H, Curtis C. Mosquito behavior and vector control. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:53–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendis C, Jacobsen JL, Gamage-Mendis A, Bule E, Dgedge M, Thompson R, et al. Anopheles arabiensis and An. funestus are equally important vectors of malaria in Matola coastal suburb of Maputo, southern Mozambique. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:171–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fornadel CM, Norris LC, Glass GE, Norri DE. Analysis of Anopheles arabiensis blood feeding behavior in southern Zambia during the two years after introduction of insecticide-treated bed nets. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:848–853. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tirados I, Costantini C, Gibson G, Torr SJ. Blood-feeding behavior of the malarial mosquito Anopheles arabiensis: implications for vector control. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:425–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2006.652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fontenille D, Lochouarn L, Diatta M, Sokhna C, Dia I, Diagne N, et al. Four years entomological study of the transmission of seasonal malaria in Senegal and the bionomics of Anopheles gambiae and An. arabiensis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:647–652. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(97)90506-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duchemin BJ, Leong Pock Tsy MJ, Rabarison P, Roux J, Coluzzi M, Costantini C. Zoophily of Anopheles arabiensis and An. gambiae in Madagascar demonstrated by odour-baited entry traps. Med Vet Entomol. 2001;15:50–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2001.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillies MT, Coetzee M. A supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara (Afrotropical region) South African Institute for Medical Research. 1987;55:1–143. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adugna N, Petros B. Determination of the human blood index of some anopheline mosquitos by using ELISA. Ethiop Med J. 1996;34:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hadis M, Lulu M, Makonnen Y, Asfaw T. Host choice by indoor-resting Anopheles arabiensis in Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:376–378. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(97)90245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massebo F, Balkew M, Gebre-Michael T, Lindtjørn B. Zoophagic behaviour of anopheline mosquitoes in southwest Ethiopia: opportunity for malaria vector control. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:645. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1264-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chirebvu E, Chimbari JM. Characterization of an indoor-resting population of Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae) and the implications on malaria transmission in Tubu Village in Okavango sub-district, Botswana. J Med Vet Entomol. 2016;53:569–576. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjw024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Githeko AK, Adungo NI, Karanja DM, Hawley WA, Vulule JM, Seroney IK, et al. Some observations on the biting behaviour of Anopheles gambiae s.s., Anopheles arabiensis, and Anopheles funestus and their implications for malaria control. Exp Parasitol. 1996;82:306–315. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taye A, Hadisa M, Adugnaa N, Tilahuna D, Wirtzb RA. Biting behavior and Plasmodium infection rates of Anopheles arabiensis from Sille, Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2006;97:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yohannes M, Boelee E. Early biting rhythm in the afro-tropical vector of malaria, Anopheles arabiensis, and challenges for its control in Ethiopia. Med Vet Entomol. 2012;26:103–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2011.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kibret S, Alemu Y, Boelee E, Tekie H, Alemu D, Petros B. The impact of a small-scale irrigation scheme on malaria transmission in Ziway area, Central Ethiopia. Tropical Med Int Health. 2010;15:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robert V, Carnevale P. Influence of deltamethrin treatment of bed nets on malaria transmission in the Kou valley, Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Org. 1991;69:735–740. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Costantini A, Ose K, Kamdem G, Antonio-Nkondjio C, Agbor J, Awono-Ambene P, et al. Habitat suitability and ecological niche profile of major malaria vectors in Cameroon. Malar J. 2009;8:307–322. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kashiwada M, Ohta S. Modeling the spatio-temporal distribution of the anopheles mosquito based on life history and surface water conditions. Open Ecol J. 2010;3:29–40. doi: 10.2174/1874213001003010029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galardo A, Zimmerman O, Lounibos L, Young L, Gardo C, Arruda M, et al. Seasonal abundance of anopheline mosquitoes and their association with rainfall and malaria along the Matap River, Amap, Brazil. MedVet Entomol. 2009;23:335–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yewhalaw D, Wassie F, Steurbaut W, Spanoghe P, Van Bortel W, Denis L, et al. Multiple insecticide resistance: an impediment to insecticide-based malaria vector control program. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathys T. Effectiveness of zooprophylaxis for malaria prevention and control in settings of complex and protracted emergency. Resil Interdiscipl Perspectives Sci Humanitar. 2010;1:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO . Manual on environmental management for mosquito control with special emphasis on malaria vectors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bulterys PL, Mharakurwa S, Thuma PE. Cattle, other domestic animal ownership, and distance between dwelling structures are associated with reduced risk of recurrent Plasmodium falciparum infection in southern Zambia. Tropical Med Int Health. 2009;14:522–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwashita H, Dida OG, Sonye OG, Sunahara T, Futami K, Njenga MS, et al. Push by a net, pull by a cow: can zooprophylaxis enhance the impact of insecticide treated bed nets on malaria control? Parasite Vectors. 2014;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto SS, Louis VR, Sie A, Sauerborn R. The effects of zooprophylaxis and other mosquito control measures against malaria in Nouna, Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2009;8:283. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Habtewold T, Walker AR, Curtis CF, Osir EO, Thapa N. The feeding behavior and Plasmodium infection of Anopheles mosquitoes in southern Ethiopia in relation to use of insecticide-treated livestock for malaria control. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:584–586. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(01)90086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaburi JC, Githuto JN, Muthami L, Ngure PK, Mueke JM, Mwandawiro CS. Effects of long-lasting insecticidal nets and zooprophylaxis on mosquito feeding behavior and density in Mwea, central Kenya. J Vector Dis. 2009;46:184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muriu MS, Muturi JE, Shililu IJ, Mbogo MC, Mwangangi MJ, Jacob GB, et al. Host choice and multiple blood feeding behaviour of malaria vectors and other anophelines in Mwea rice scheme, Kenya. Malar J. 2008;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahande AM, Mosha FW, Mahande JM, Kweka EJ. Feeding and resting behavior of malaria vector, Anopheles arabiensis with reference to zooprophylaxis. Malaria J. 2007;6:100. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bogh C, Clarke SE, Pinder M, Sanyang F, Lindsay SW. Effect of passive Zooprophylaxis on malaria transmission in the Gambia. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:822–828. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.6.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bogh C, Clarke SE, Walraven GEL, Lindsay SW. Zooprophylaxis, artefact or reality? A paired-cohort study of the effect of passive zooprophylaxis on malaria in the Gambia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:593–596. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(02)90320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lyimo IN, Ng'habi KR, Mpingwa MW, Daraja AA, Mwasheshe DD, Nchimbi NS, et al. Does cattle milieu provide a potential point to target wild exophilic Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae) with Entomopathogenic fungus? A bioinsecticide Zooprophylaxis strategy for vector control. J Parasitol Res. 2012; doi:10.1155/2012/280583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Fritz ML, Siegert PY, Walker ED, Bayoh HMN, Vulule JR, Miller JR. Toxicity of blood meals from ivermectin-treated cattle to Anopheles gambiae s.l. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:539–547. doi: 10.1179/000349809X12459740922138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rowland M, Durrani N, Kenward M, Mohammed N, Urahman H, Hewitt S. Control of malaria in Pakistan by applying deltamethrin insecticide to cattle: a community-randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1837–1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04955-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foley DH, Bryan JH, Lawrence GW. The potential of Ivermectin to control the malaria vector Anopheles farauti. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:625–628. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hewitt S, Rowland M. Control of zoophilic malaria vectors by applying pyrethroid insecticides to cattle. Tropical Med Int Health. 1999;4:481–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Habtewold T, Prior A, Torr SJ, Gibson G. Could insecticide-treated cattle reduce Afrotropical malaria transmission? Effects of deltamethrin-treated zebu on Anopheles arabiensis behavior and survival in Ethiopia. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:408–417. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Temu EA, Coleman M, Abilio AP, Kleinschmidt I. High prevalence of malaria in Zambezia, Mozambique: the protective effect of IRS versus increased risks due to pig-keeping and house construction. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Palsson K, Thomas GT, Dias JF, Laugen AT, Bjorkman A. Endophilic Anopheles mosquitoes in Guinea Bissau, West Africa, in relation to human housing conditions. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:746–752. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bouma M, Rowland M. Failure of passive zooprophylaxis: cattle ownership in Pakistan is associated with a higher prevalence of malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:351–353. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Githinji S, Herbst S, Kistemann T. The human ecology of malaria in a highland region of Southwest Kenya. Schattauer. 2009;48:451–453. doi: 10.3414/ME9242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deressa W, Ali A, Berhane Y. Household and socioeconomic factors associated with childhood febrile illnesses and treatment seeking behavior in an area of epidemic malaria in rural Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:939–947. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ghebreyesus TA, Haile M, Witten KH, Getachew AH, Yohannes M, Lindsay SW, et al. Household risk factors for malaria amongst children in the Ethiopian highlands. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:17–21. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tirados I, Gibson G, Young S, Torr SJ. Are herders protected by their herds? An experimental analysis of zooprophylaxis against the malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis. Malar J. 2011;10:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seyoum A, Balcha F, Balkew M, Ali A, Gebre-Michael G. Impact of cattle keeping on human biting rate of Anopheline mosquitoes and malaria transmission around Ziway, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2002;79:485–490. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i9.9121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hassanali A, Nedorezov LV, Sadykov AM. Zooprophylactic diversion of mosquitoes from human to alternative hosts: a static simulation model. Ecol Model. 2008;212:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawaguchi I, Sasaki A, Mogi M. Combining zooprophylaxis and insecticide spraying: a malaria-control strategy limiting the development of insecticide resistance in vector mosquitoes. Proc R Soc Lond [Biol] 2004;271:301–309. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saul A. Zooprophylaxis or zoopotentiation: the outcome of introducing animals on vector transmission is highly dependent on the mosquito mortality while searching. Malar J. 2003;2:32. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-2-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Franco OM, Gomes MG, Rowland M, Coleman GP, Davies RC. Controlling malaria using livestock-based interventions: a one health approach. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nah K, Kima Y, Lee JM. The dilution effect of the domestic animal population on the transmission of P. vivax malaria. J Theor Biol. 2010;226:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levens W. Mathematical Modelling of co-application of long lasting insecticidal nets and insecticides Zooprophylaxis against the resilience of anopheles Arabiensis for effective malaria prevention, A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of University of Dar es Salaam for the degree of master of science (mathematical Modelling). Dar es Salaam: University of Dar es Salaam; 2013.

- 78.Killeen FG, Smith AT. Exploring the contributions of bed nets, cattle, insecticides and excito-repellency to malaria control: a deterministic model of mosquito host-seeking behaviour and mortality. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:867–880. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Animut A, Balkew M, Gebre-Michael T, Lindtjørn B. Blood meal sources and entomological inoculation rates of anophelines along a highland altitudinal transect in south-central Ethiopia. Malar J. 2013;12:76. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kent JR, Thuma EP, Mharakurwa S, Norris ED. Seasonality, blood feeding behavior and transmission of Plasmodium falciparum by Anopheles arabiensis after an extended drought in southern Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:267–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Idrees M, Jan AH. Failure of Zooprophylaxis: cattle ownership increase rather than reduce the prevalence of malaria in district dir, NWFP of Pakistan. J Med Sci. 2001;1:52–54. doi: 10.3923/jms.2001.52.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mayagaya SV, Nkwengulila G, Lyimo NI, Kihonda J, Mtambala H, et al. The impact of livestock on the abundance, resting behaviour and sporozoite rate of malaria vectors in southern Tanzania. Malar J. 2015;14:17. doi: 10.1186/s12936-014-0536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mahande AM, Mosha FW, Mahande JM, Kweka EJ. Role of cattle treated with deltamethrin in areas with a high population of Anopheles arabiensis in Moshi, Northern Tanzania. Malar J. 2007;6:109. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Killeen FG, Ellis McKenzie F, Foy DB, Bøgh C, Beier CJ. The availability of potential hosts as a determinant of feeding behaviors and malaria transmission by African mosquito populations. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:469–476. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(01)90005-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets were generated or analysed during this scoping review.