Abstract

Background

Endometriosis is a condition with relatively non-specific symptoms, and in some cases a long time elapses from first-symptom presentation to diagnosis.

Aim

To develop and test new composite pointers to a diagnosis of endometriosis in primary care electronic records.

Design and setting

This is a nested case-control study of 366 cases using the Practice Team Information database of anonymised primary care electronic health records from Scotland. Data were analysed from 366 cases of endometriosis between 1994 and 2010, and two sets of age and GP practice matched controls: (a) 1453 randomly selected females and (b) 610 females whose records contained codes indicating consultation for gynaecological symptoms.

Method

Composite pointers comprised patterns of symptoms, prescribing, or investigations, in combination or over time. Conditional logistic regression was used to examine the presence of both new and established pointers during the 3 years before diagnosis of endometriosis and to identify time of appearance.

Results

A number of composite pointers that were strongly predictive of endometriosis were observed. These included pain and menstrual symptoms occurring within the same year (odds ratio [OR] 6.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.9 to 10.6), and lower gastrointestinal symptoms occurring within 90 days of gynaecological pain (OR 6.1, 95% CI = 3.6 to 10.6). Although the association of infertility with endometriosis was only detectable in the year before diagnosis, several pain-related features were associated with endometriosis several years earlier.

Conclusion

Useful composite pointers to a diagnosis of endometriosis in GP records were identified. Some of these were present several years before the diagnosis and may be valuable targets for diagnostic support systems.

Keywords: diagnosis, electronic health records, endometriosis, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is a common gynaecological condition in which there is often a long time between first primary care consultation and diagnosis.1–4 A longer time to diagnosis is associated with prolonged symptoms, particularly pain and5,6 subfertility, along with patient frustration and demoralisation.7 Endometriosis can be difficult to diagnose clinically; its symptoms are both common8 and non-specific, so are often considered by GPs as part of the normal menstrual experience,9 or attributed to other conditions.5 The use of very detailed questions about symptoms can increase diagnostic accuracy.10 However, current biomarkers11 and imaging12 have limited benefit, and there is substantial variation in guideline recommendations for diagnosis and management of this condition.13

Most research on the clinical features of endometriosis in primary care has focused on features present at a single point in time, typically the time of diagnosis.5,14 However, with endometriosis, the symptoms at any single point in time have only limited predictive value2 and the problem of delays in diagnosis requires an understanding of when symptoms first appear. Although data in electronic records contain many single items, experienced practitioners typically recognise composite patterns that involve combinations of items. For example, repeated episodes of dysmenorrhoea, except when taking hormonal contraception,15 are recognised by experienced clinicians as having diagnostic value in endometriosis. Although such knowledge-derived features16 are not immediately present in electronic records, they can be constructed.17 However, the authors are not aware of studies that have attempted to do this using primary care data or for endometriosis.

This study aimed to: (a) construct enriched datasets from electronic health records, which contained conventional and composite features potentially predictive of endometriosis; (b) examine the association of these features with a subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis in a nested case-control study; and (c) examine the relationship of these features to diagnosis at different time periods before the date of diagnosis.

METHOD

Data source

Data from the Practice Team Information (PTI) database, a subset of the Primary Care Clinical Informatics Unit Research database held by the University of Aberdeen, were obtained. It includes anonymised data from primary care electronic health records of approximately 224 000 patients registered with a primary care physician, and is broadly representative of the Scottish population with regards to age, sex, deprivation, and urban/rural ratio mix. It includes data collected annually between 2004 and 2010. Practices in the PTI project were expected to record every clinical encounter using Read Codes for clinical diagnoses and/or main reasons for consultation. All GP prescriptions were automatically recorded. Investigations and therapeutic procedures were coded differently over time — increasing towards the end of the database period.

How this fits in

Endometriosis is a relatively common condition but the time from first presentation to diagnosis is often longer than ideal as symptoms are non-specific. This study used anonymised GP record data to construct new pointers to diagnosis, which identified patterns of symptoms in time. Distinct episodes of gynaecological pain and combinations of gynaecological pain on one occasion with menstrual symptoms or lower gastrointestinal symptoms on another appear to be useful pointers to endometriosis. Patterns such as these make sense to clinicians and could be integrated into electronic diagnostic support systems.

Populations

This study was a nested case-control study. Cases were females with a diagnosis of endometriosis, who were born after 1 January 1974 and were, therefore, ≤36 years on 1 January 2010. This enabled us to capture teenage menstrual symptoms for the majority of females and avoid the possibility that an apparent new diagnosis in an older female was actually a historical diagnosis being recorded for the first time due to the creation of computerised record summaries.

Population controls were randomly selected for each case and individually matched by age and GP practice, with up to four controls per case (subject to availability). A second control group comprised females with codes for gynaecological symptoms (pain, menstrual symptoms, or infertility) but with no recorded diagnosis of endometriosis. These controls were also randomly selected for each case and individually matched by age and GP practice, with up to four symptomatic controls per case. The index date for cases was defined as the date of diagnosis of endometriosis and for controls as the date of diagnosis of endometriosis in the matched case. All cases and controls were required to have been registered with their GP practice for at least 1 year before the index date.

Data extraction and preparation

Box 1 lists the key data extracted and the categories into which related items were grouped. Most items were allocated to a single time point. However, for contraception prescriptions, which commonly lasted for 6 months or longer, details were used about each prescription to estimate the onset and offset of contraception using methods previously employed to ascertain the continuity of prescribing.18

Box 1. Categories of data grouped by data type.

| Data type | Data description | Included data categories |

|---|---|---|

| Specific features | Classical features of endometriosis (pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia and infertility)2,5,9,14 | Pain (pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea) Menstrual (flow) Infertility Ovarian (for example, cysts) |

| Non-specific symptoms | Abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, urinary symptoms; additional diagnoses, including irritable bowel syndrome5 | Menstrual (timing) Genital/other gynaecological Urinary Lower GI Upper GI Fatigue |

| Diagnostic tests and procedures | Primary care tests, referred investigations such as diagnostic ultrasound, and specialist procedures such as laparoscopy | Full blood count Genital swabs Laparoscopy Abdominal or pelvic ultrasound Thyroid function |

| Treatments | Hormonal treatment for endometriosis (for example, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) Prescriptions for contraception Analgesic drugs Antidepressant drugs |

Hormonal treatment Contraception NSAID Codeine or other opioids Tricyclic SSRI and related antidepressants |

Lower GI = pain, bloating, irritable bowel syndrome. NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Upper GI = dyspepsia, reflux, nausea.

The data was enriched by introducing composite features that were based on the clinical experience of the investigators and on interviews with 10 experts (six gynaecologists, two specialists in reproductive health, and two representatives of a lay support organisation). Interviews sought to identify tacit patterns in symptoms, which clinicians thought may be predictive of a diagnosis, were audio recorded, transcribed, and analysed thematically. Composite features were specified according to one of five relationships: proximity, following, separated, during, and exclusive. These are summarised in Box 2.

Box 2. Types of composite features used in constructing predictors.

| Relationship | Specification | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Proximity | An occurrence of one feature within a given number of days of the other but with no specification of which should come first | Pain and fatigue within 90 days of each other |

| Following | An occurrence of one feature within a given number of days of the other with specification of which should come first | Pain occurring within 90 days of estimated cessation of contraception |

| Separated | Two consecutive recordings of a single feature occurring at least a given number of days apart (this permits differentiation of separate episodes from repeated consultation during the same episode) | Two consecutive episodes of pain separated by at least 180 days |

| During | An occurrence of a symptom or other feature after the onset, and before the expected offset, of a contraception prescription | Pain during estimated duration of prescription for contraception |

| Exclusive | A feature only occurring in the absence of another | Pain but only outside of estimated periods of prescribed contraception |

The presence of each feature (single and composite) was ascertained in the record of each individual at any time, and during a series of overlapping 3-year time windows set at different intervals from the index date (for diagnosis or matching). The windows were defined using intervals between the end of the window and the index date of 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months. The appearance of statistical associations between available information in the record and diagnosis over time were examined by comparing the same measure in different windows. The purpose of this was to differentiate between features that were present long before diagnosis (and may thus indicate missed diagnostic opportunities) and those that appeared only shortly before diagnosis (and may thus have triggered referral).

Analysis of association of features and patterns with diagnosis

Conditional logistic regression was carried out to examine the association between each feature (conventional or composite) and the diagnosis of endometriosis. Each feature was reported as either present or absent within the time period. Rather than use counts of how often a feature occurred, the ‘separated’ composite variables were used to indicate multiple episodes. Conditional logistic regression was conducted for all features for which at least 10 individuals (cases or controls) had the feature present and reported as the odds ratio (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were conducted in R 3.3.2 (version 2016).

The analysis was conducted separately with population and symptomatic control groups. For the population comparison all cases and their matched controls were included. For the symptomatic comparison, only cases that had recorded symptoms and their matched controls were included. For the time window analysis, the data were limited to females who had been registered with their practice for at least 1 year before the beginning of the gap. The odds ratios for each feature at each of the six different time gaps were plotted in order to visualise the appearance of predictive features over time.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Data from 366 cases and 1453 matched population controls were obtained. Of these, 243 cases had gynaecological symptoms (pain, menstrual symptoms, and infertility) and were matched to a further 610 controls with comparable symptoms. The median age at diagnosis was 25 years, interquartile range 22–28 years, and age at diagnosis was <20 years in 47 (12.8%) cases.

Data quality

In total, 191 cases (52.2%) were registered with the same GP practice for at least 5 years before diagnosis and, therefore, had continuous records in the PTI database; 114 (31.2%) were registered for at least 8 years before diagnosis. Similar proportions were seen for population controls (746 [51.3%] and 469 [32.3%] respectively), but more of the symptomatic controls had been registered for these time periods (414/610, 67.9% and 273/610, 44.8%). A recorded code for laparoscopy was found in only 47 (12.8%) cases despite this being the commonest diagnostic procedure for endometriosis. This is likely to represent a preference for recording the diagnosis rather than the procedure by which it was made, although instances of a clinical diagnosis being entered without any confirmatory tests cannot be excluded. Likewise, there were few coded surgical procedures, for example, 13 cases (3.5%) had a recorded operation for tubal or ovarian problems excluding diagnostic laparoscopy. These procedures were excluded from the analysis, focusing instead on clinical features, investigations, and medical treatments.

Occurrence of diagnostic features

There were 145 cases (39.6%) that had a code recorded for gynaecological pain (dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain) during the 3 years prior to diagnosis and 39 (10.7%) had a code for infertility. And 198 cases (54.1%) had neither of these during the 3 years prior to diagnosis.

The numbers and proportions of females with at least one instance of each feature, either in the 3 years prior to the index date or at any time, are shown in Table 1 (all cases [N = 366] and population controls) and Table 2 (symptomatic cases [N = 261] and controls). Table 1 and Table 2 also show the odds ratios (OR), with 95% CIs for the two comparisons: all cases versus population controls and symptomatic cases (gynaecological pain, menstrual symptoms, or infertility) versus matched symptomatic controls.

Table 1.

Numbers, proportions, and odds ratios (95% CI) for features in cases of endometriosis compared with population controls

| Specific features | Occurrence of features in 3 years before index datea | Occurrence of features at any time before index datea | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (N= 366) | Controls (N= 1453) | Cases (N= 366) | Controls (N= 1453) | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | |

| Subfertility | 39 | 10.7 | 24 | 1.7 | 7.7 | (4.4 to 13.3) | 41 | 11.2 | 31 | 2.1 | 5.9 | (3.6 to 9.7) |

| Menstrual — bleeding | 121 | 33.1 | 179 | 12.3 | 3.8 | (2.8 to 5.0) | 151 | 41.3 | 267 | 18.4 | 3.3 | (2.6 to 4.3) |

| Menstrual — timing | 39 | 10.7 | 80 | 5.5 | 2.1 | (1.4 to 3.2) | 45 | 12.3 | 117 | 8.1 | 1.6 | (1.1 to 2.3) |

| Ovarian | 24 | 6.6 | 7 | 0.5 | 13.7 | (5.9 to 31.8) | 25 | 6.8 | 11 | 0.8 | 9.8 | (4.7 to 20.4) |

| Pain | 145 | 39.6 | 79 | 5.4 | 14.9 | (10.1 to 21.9) | 169 | 46.2 | 146 | 10.1 | 9.9 | (7.1 to 13.6) |

| Non-specific symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Fatigue | 56 | 15.3 | 121 | 8.3 | 2.0 | (1.4 to 2.8) | 79 | 21.6 | 178 | 12.3 | 2.0 | (1.5 to 2.7) |

| Gynaecological | 51 | 13.9 | 47 | 3.2 | 5.0 | (3.3 to 7.7) | 77 | 21.0 | 97 | 6.7 | 4.0 | (2.8 to 5.6) |

| Lower GI | 104 | 28.4 | 144 | 9.9 | 3.7 | (2.8 to 5.0) | 126 | 34.4 | 213 | 14.7 | 3.3 | (2.5 to 4.3) |

| Upper GI | 27 | 7.4 | 62 | 4.3 | 1.8 | (1.1 to 3.0) | 50 | 13.7 | 107 | 7.4 | 2.1 | (1.4 to 3.0) |

| Urinary | 25 | 6.8 | 49 | 3.4 | 2.1 | (1.3 to 3.5) | 42 | 11.5 | 80 | 5.5 | 2.3 | (1.5 to 3.5) |

| Tests and procedures | ||||||||||||

| Full blood count | 40 | 10.9 | 102 | 7.0 | 2.0 | (1.2 to 3.2) | 50 | 13.7 | 112 | 7.7 | 2.6 | (1.6 to 4.2) |

| Genital swabs | 64 | 17.5 | 77 | 5.3 | 4.5 | (3.0 to 6.7) | 73 | 20.0 | 111 | 7.6 | 3.5 | (2.5 to 5.0) |

| Laparoscopy | 42 | 11.5 | 13 | 0.9 | 14.6 | (7.5 to 28.4) | 47 | 12.8 | 15 | 1.0 | 13.9 | (7.5 to 25.7) |

| Thyroid function | 53 | 14.5 | 112 | 7.7 | 2.4 | (1.6 to 3.5) | 67 | 18.3 | 132 | 9.1 | 2.8 | (1.9 to 4.1) |

| Ultrasound | 14 | 3.8 | 5 | 0.3 | 12.3 | (4.0 to 37.8) | 14 | 3.8 | 11 | 0.8 | 5.0 | (2.2 to 11.4) |

| Treatments | ||||||||||||

| Contraception | 201 | 54.9 | 716 | 49.3 | 1.3 | (1.0 to 1.6) | 234 | 63.9 | 800 | 55.1 | 1.5 | (1.2 to 2.0) |

| NSAID | 171 | 46.7 | 276 | 19.0 | 4.8 | (3.6 to 6.4) | 191 | 52.2 | 393 | 27.1 | 3.8 | (2.9 to 5.1) |

| Analgesic | 136 | 37.2 | 254 | 17.5 | 3.0 | (2.3 to 4.0) | 156 | 42.6 | 343 | 23.6 | 2.7 | (2.1 to 3.5) |

| SSRI | 65 | 17.8 | 188 | 12.9 | 1.5 | (1.1 to 2.0) | 85 | 23.2 | 229 | 15.8 | 1.7 | (1.2 to 2.2) |

| Tricyclic | 29 | 7.9 | 60 | 4.1 | 2.2 | (1.3 to 3.6) | 42 | 11.5 | 82 | 5.6 | 2.4 | (1.6 to 3.6) |

Index date: date of diagnosis for cases, date of diagnosis of matched case for controls. CI = confidence interval. Gynaecological = vulvo-vaginal symptoms, pelvic inflammation. Lower GI = pain, bloating, irritable bowel syndrome. NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. OR = odds ratio. Ovarian = coded diagnosis of ovarian cysts and related conditions. SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and related antidepressants. Upper GI = dyspepsia, reflux, nausea.

Table 2.

Numbers, proportions, and odds ratios (95% CI) for features in cases of endometriosis compared with symptomatic controls

| Occurrence of features in 3 years before index datea | Occurrence of features at any time before index datea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (N= 261) | Controls (N= 610) | Cases (N= 261) | Controls (N= 610) | |||||||||

| Specific features | N | % | N | % | OR | 95% CI | N | % | N | % | OR | 95% CI |

| Subfertility | 39 | 16.1 | 52 | 8.5 | 2.4 | (1.4 to 3.9) | 41 | 16.9 | 64 | 10.5 | 1.9 | (1.2 to 3.1) |

| Menstrual — bleeding | 121 | 49.8 | 304 | 49.8 | 1.0 | (0.7 to 1.4) | 151 | 62.1 | 443 | 72.6 | 0.7 | (0.5 to 0.9) |

| Menstrual — timing | 30 | 12.4 | 64 | 10.5 | 1.2 | (0.7 to 1.9) | 34 | 14.0 | 111 | 18.2 | 0.7 | (0.5 to 1.1) |

| Ovarian | 14 | 5.8 | 3 | 0.5 | 12.2 | (3.5 to 42.7) | 15 | 6.2 | 6 | 1.0 | 7.0 | (2.7 to 18.1) |

| Pain | 145 | 59.7 | 148 | 24.3 | 5.6 | (3.9 to 8.1) | 169 | 69.6 | 241 | 39.5 | 4.0 | (2.8 to 5.6) |

| Non-specific symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Fatigue | 45 | 18.5 | 84 | 13.8 | 1.4 | (0.9 to 2.1) | 66 | 27.2 | 138 | 22.6 | 1.3 | (0.9 to 1.9) |

| Gynaecological | 41 | 16.9 | 34 | 5.6 | 4.2 | (2.4 to 7.4) | 64 | 26.3 | 68 | 11.2 | 3.6 | (2.3 to 5.6) |

| Lower GI | 79 | 32.5 | 109 | 17.9 | 2.3 | (1.6 to 3.2) | 95 | 39.1 | 180 | 29.5 | 1.7 | (1.2 to 2.3) |

| Upper GI | 24 | 9.9 | 51 | 8.4 | 1.3 | (0.8 to 2.3) | 44 | 18.1 | 87 | 14.3 | 1.5 | (1.0 to 2.3) |

| Urinary | 20 | 8.2 | 29 | 4.8 | 1.8 | (1.0 to 3.4) | 36 | 14.8 | 64 | 10.5 | 1.5 | (1.0 to 2.4) |

| Tests and procedures | ||||||||||||

| Full blood count | 34 | 14.0 | 82 | 13.4 | 1.2 | (0.7 to 2.2) | 42 | 17.3 | 97 | 15.9 | 1.4 | (0.8 to 2.4) |

| Genital swabs | 43 | 17.7 | 71 | 11.6 | 2.2 | (1.3 to 3.5) | 50 | 20.6 | 90 | 14.8 | 1.9 | (1.2 to 3.0) |

| Laparoscopy | 31 | 12.8 | 4 | 0.7 | 20.0 | (7.0 to 57.1) | 35 | 14.4 | 13 | 2.1 | 7.2 | (3.7 to 14.1) |

| Thyroid function | 43 | 17.7 | 86 | 14.1 | 1.5 | (0.9 to 2.4) | 53 | 21.8 | 103 | 16.9 | 1.7 | (1.1 to 2.7) |

| Ultrasound | 11 | 4.5 | 6 | 1.0 | 5.2 | (1.6 to 17.0) | 11 | 4.5 | 7 | 1.2 | 4.3 | (1.4 to 13.0) |

| Treatments | ||||||||||||

| Contraception | 151 | 62.1 | 373 | 61.2 | 1.1 | (0.8 to 1.5) | 178 | 73.3 | 421 | 69.0 | 1.3 | (0.9 to 1.9) |

| NSAID | 133 | 54.7 | 185 | 30.3 | 3.0 | (2.1 to 4.2) | 150 | 61.7 | 264 | 43.3 | 2.6 | (1.8 to 3.7) |

| Analgesic | 100 | 41.2 | 142 | 23.3 | 2.7 | (1.9 to 3.9) | 116 | 47.7 | 203 | 33.3 | 2.3 | (1.6 to 3.4) |

| SSRI | 43 | 17.7 | 115 | 18.9 | 1.0 | (0.7 to 1.5) | 57 | 23.5 | 148 | 24.3 | 1.1 | (0.8 to 1.6) |

| Tricyclic | 20 | 8.2 | 37 | 6.1 | 1.5 | (0.8 to 2.7) | 29 | 11.9 | 58 | 9.5 | 1.3 | (0.8 to 2.1) |

Index date: date of diagnosis for cases, date of diagnosis of matched case for controls. CI = confidence interval. Gynaecological = vulvo-vaginal symptoms, pelvic inflammation. Lower GI = pain, bloating, irritable bowel syndrome. NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. OR = odds ratio. Ovarian = coded diagnosis of ovarian cysts and related conditions. SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and related antidepressants. Upper GI = dyspepsia, reflux, nausea.

As expected, pain was more common in cases in both comparisons: OR 14.9, 95% CI = 10.1 to 21.9 versus population controls and OR 5.6, 95% CI = 3.9 to 8.1 versus symptomatic controls over 3 years’ data. Menstrual bleeding and timing symptoms were coded more commonly than in population controls, OR 3.8, 95% CI = 2.8 to 5.0 and 2.1, 95% CI = 1.4 to 3.2, but not in comparison with symptomatic controls, OR 1.0, 95% CI = 0.7 to 1.4 and 1.2, 95% CI = 0.7 to 1.9. Non-specific clinical features such as fatigue, vulvo-vaginal problems, and lower gastrointestinal symptoms were all more common in cases than population controls.

Although simple tests such as full blood count were more common in cases than population controls, there was no significant difference in the symptomatic comparison. Genitourinary swab tests (presumably ordered because of the possibility that symptoms were due to pelvic inflammation) were more common in cases than controls in both comparisons.

Occurrence of prescribed treatments

In both the population and the symptomatic group comparisons, both analgesics (OR 3.0, 95% CI = 2.3 to 4.0 and OR 2.7, 95% CI = 1.9 to 3.9, in 3 years before index date comparison) and NSAIDs (OR 4.8, 95% CI = 3.6 to 6.4 and OR 3.0, 95% CI = 2.1 to 4.2, in 3 years before index date comparison) were more commonly prescribed to cases than controls. When comparing cases and symptomatic controls, there was no association with antidepressant drugs (either tricyclic or SSRI and related).

Composite features

Table 3 shows the number and proportion of patients with at least one instance of each of the composite features over the 3 years before date of diagnosis/matching. Several composite features had high ORs when cases were compared with symptomatic controls: pain and menstrual symptoms within the same year (pain proximity menstrual [360]), OR 6.5, 95% CI = 3.9 to 10.6 and lower gastrointestinal symptoms occurring within 90 days of gynaecological pain (OR 6.1, 95% CI = 3.6 to 10.6). Episodes of gynaecological pain separated by at least 180 days were approximately eight times as likely in cases than symptomatic controls (OR 8.5, 95% CI = 4.3 to 16.9). Although pain or analgesic use on stopping contraception was suggested by some of the experts, these composite features occurred in less than 10% of cases, and with only moderate ORs of approximately 3.

Table 3.

Numbers, proportions, and odds ratios (95% CI) for composite features in the 3 years before diagnosis/matchinga

| Composite feature | Comparison with population controls | Comparison with symptomatic controls | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (N= 366) | Controls (N = 1453) | Cases (N= 261) | Controls (N= 610) | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | |

| Pain during contraception | 40 | 10.9 | 24 | 1.7 | 7.4 | (4.3 to 12.7) | 40 | 16.5 | 38 | 6.2 | 3.0 | (1.9 to 5.0) |

| Pain follow contraception (180) | 17 | 4.6 | 8 | 0.6 | 8.5 | (3.7 to 19.7) | 17 | 7.0 | 17 | 2.8 | 3.1 | (1.5 to 6.4) |

| Pain exclusive contraception | 105 | 28.7 | 55 | 3.8 | 14.2 | (9.1 to 22.0) | 105 | 43.2 | 110 | 18.0 | 4.3 | (2.9 to 6.2) |

| Menstrual during contraception | 38 | 10.4 | 65 | 4.5 | 2.6 | (1.7 to 4.1) | 38 | 15.6 | 87 | 14.3 | 1.1 | (0.7 to 1.8) |

| Menstrual follow contraception (180) | 14 | 3.8 | 8 | 0.6 | 7.0 | (2.9 to 16.7) | 14 | 5.8 | 17 | 2.8 | 2.0 | (1.0 to 4.2) |

| Analgesic during contraception | 51 | 13.9 | 90 | 6.2 | 2.5 | (1.7 to 3.7) | 39 | 16.1 | 59 | 9.7 | 2.0 | (1.3 to 3.1) |

| Analgesic follow contraception (180) | 27 | 7.4 | 26 | 1.8 | 4.5 | (2.5 to 7.8) | 21 | 8.6 | 21 | 3.4 | 2.8 | (1.5 to 5.3) |

| Analgesic exclusive contraception | 116 | 31.7 | 68 | 4.7 | 12.0 | (8.1 to 17.8) | 116 | 47.7 | 132 | 21.6 | 3.9 | (2.7 to 5.6) |

| NSAID during contraception | 56 | 15.3 | 92 | 6.3 | 2.9 | (2.0 to 4.2) | 48 | 19.8 | 68 | 11.2 | 2.0 | (1.3 to 3.0) |

| NSAID follow contraception (90) | 27 | 7.4 | 28 | 1.9 | 4.0 | (2.3 to 6.8) | 21 | 8.6 | 19 | 3.1 | 3.0 | (1.6 to 5.8) |

| Pain proximity menstrual (360) | 61 | 16.7 | 23 | 1.6 | 15.1 | (8.5 to 26.6) | 61 | 25.1 | 34 | 5.6 | 6.5 | (3.9 to 10.6) |

| Analgesic proximity menstrual (90) | 29 | 7.9 | 19 | 1.3 | 6.3 | (3.5 to 11.4) | 29 | 11.9 | 30 | 4.9 | 2.6 | (1.5 to 4.6) |

| Analgesic proximity pain (90) | 45 | 12.3 | 15 | 1.0 | 15.5 | (8.0 to 30.1) | 45 | 18.5 | 20 | 3.3 | 7.1 | (4.0 to 12.5) |

| NSAID proximity pain (90) | 63 | 17.2 | 28 | 1.9 | 10.9 | (6.7 to 17.7) | 63 | 25.9 | 40 | 6.6 | 6.0 | (3.7 to 9.7) |

| Lower GI proximity pain (90) | 48 | 13.1 | 12 | 0.8 | 15.9 | (8.4 to 29.9) | 48 | 19.8 | 24 | 3.9 | 6.1 | (3.6 to 10.6) |

| Lower GI proximity menstrual (90) | 35 | 9.6 | 23 | 1.6 | 6.3 | (3.7 to 10.7) | 35 | 14.4 | 39 | 6.4 | 2.6 | (1.6 to 4.1) |

| Pain separated by >180 days | 36 | 9.8 | 14 | 1.0 | 12.5 | (6.3 to 24.6) | 36 | 14.8 | 14 | 2.3 | 8.5 | (4.3 to 16.9) |

Composite feature names follow the format X relationship Y [N] where relationship is defined as follows:

X during Y; only used where Y = contraception. X = feature and occurs at least once after the onset date and before the expected offset date of at least one contraceptive prescription.

X follow Y (N); N = number of days. Y = discrete time point event. X = feature and occurs between 1 and N days after Y. Where Y = contraception, N days relate to the expected offset date. X proximity Y (N); used where X and Y = discrete time point events and N is a number of days. X occurs between N days before and N days after Y. X exclusive Y; currently only used where Y = contraception: X = feature. X and Y are present but criteria for X during Y are never met. A single prescription of contraception occurring on the same day as a code for dysmenorrhoea would meet X exclusive Y criteria as X during Y requires X after the onset of contraception. X separated by >(N) days; two consecutive occurrences of X separated by more than N days.

CI = confidence interval. GI = gastrointestinal. NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. OR = odds ratio.

Occurrence of diagnostic features over the time prior to diagnosis

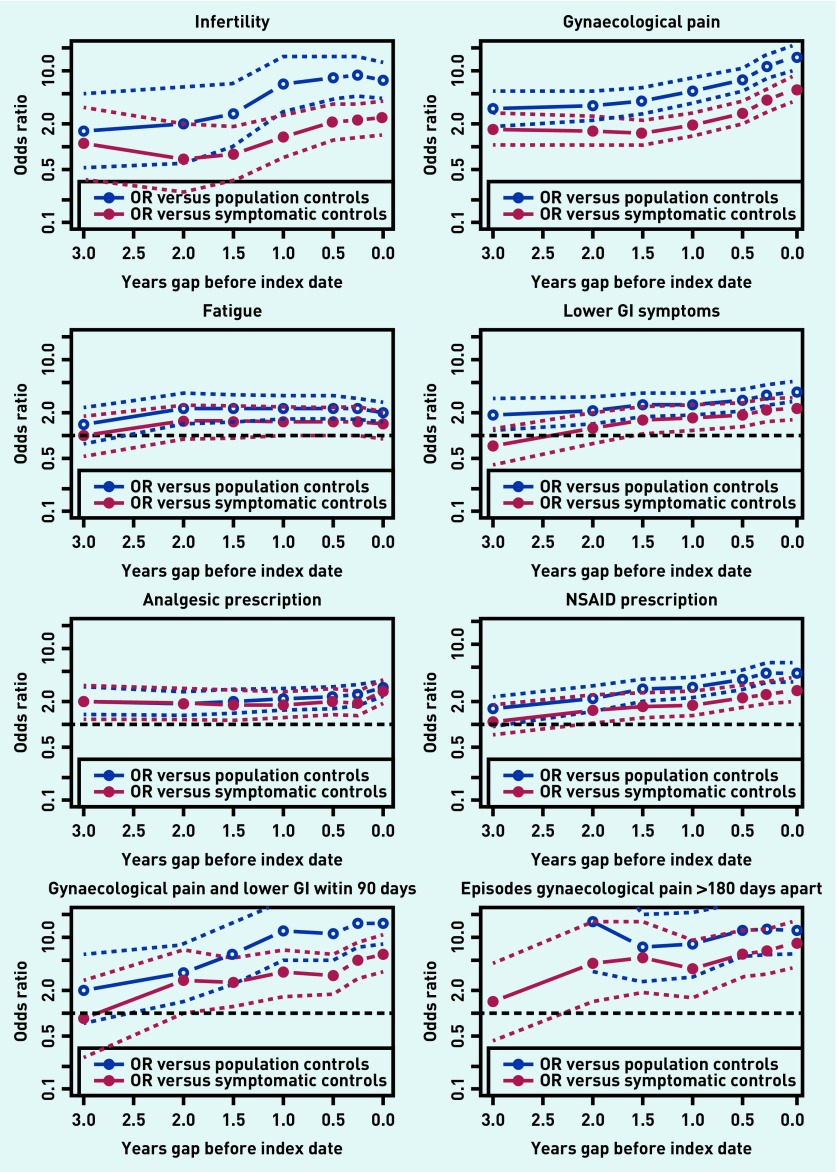

Figure 1 shows plots of eight diagnostic features, describing the ORs for 3-year time windows with different intervals between the end of the 3-year window and the diagnosis/matching date. Each plot compares cases with matched population controls and symptomatic cases with their matched symptomatic controls. In all plots, 95% CIs are indicated. These show differing patterns.

Figure 1.

Plots of OR for individual features over 3 years, by gap between the end of the 3-year window and the date of diagnosis/matching. Dotted lines indicate 95% CI for ORs. CI = confidence interval. OR = odds ratio.

The plot for fertility problems (infertility) shows that until 1.5 years before diagnosis there was no association with a diagnosis of endometriosis, but from there the OR increased until about 0.5 years before diagnosis, at which point it stayed elevated. This is interpreted as indicating that the time delay from the occurrence of infertility to diagnosis is relatively short, presumably as infertility leads to referral including diagnostic laparoscopy.

The plot for gynaecological pain shows that the OR was significantly elevated several years prior to diagnosis and that this increased in the year prior to diagnosis (at least in the population comparison). The two plots for non-specific symptoms (fatigue and lower gastrointestinal symptoms) show patterns of longstanding modest elevation.

The bottom row of plots in Figure 1 shows two composite features: lower GI symptoms within 90 days of gynaecological pain and episodes of gynaecological pain >180 days apart. Although CIs for these composites were wider there was a suggestion of a trend over time in the lower GI plus pain combination.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study has two important new findings. First, the predictive value of several composite features for a subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis in routine records was evaluated. Second, for the first time, different time trends in the appearance of recorded clinical features of endometriosis were demonstrated.

Strengths and limitations

The choice of features as pointers used principles of feature selection based on expert input,19 and methods of data consolidation and aggregation that have been developed for use with clinical data sources other than GP records.17,20 This sequence of steps is broadly comparable with other recent approaches to the summarisation of clinical data.20,21 An established anonymised GP record set was used that contained both diagnostic and symptom codes using the Read Code format, which means that the method is transferable to other research datasets and potentially to clinical use.

There were limitations relating to the data, as the data were from standalone primary care records with no linkage to secondary care records, meaning that the reliability of GPs’ diagnoses of endometriosis could not be assessed. However, in the authors’ experience, GP practices tend not to code such diagnoses without specialist opinion. The data were more sparse than anticipated, with only around half of cases having cardinal clinical features of endometriosis recorded prior to diagnosis. This probably reflects the limited use of symptom codes by GPs, even in this database where a reason for consultation was meant to be given for each attendance. The rates of coding of procedures such as laparoscopy was surprisingly low; the authors suspect this is because GP practices had coded the findings of the laparoscopy rather than the procedure itself. Finally, as the duration of the database was shorter than a female’s reproductive period, a decision was made to exclude some females aged >35 years and diagnosed with endometriosis in order to maintain a focus on females for whom electronic health records were more likely to have data about earlier menstrual and related symptoms.

Comparison with existing literature

The authors are not aware of other studies that have looked for combinations of features in time as predictors of diagnoses in GP records. Although combinations of symptoms are commonly used in cancer prediction tools, these are usually simply recorded as present or absent,22 whereas in this study temporal relationships were specified in order to increase the specificity of pointers. Other studies of endometriosis have only reported single items.5

Implications for research and practice

The composite predictors of a diagnosis of endometriosis variables reflect the patterns that clinicians observe, and, for the first time, they have been tested using data in routine GP records over time. These combinations — including pain and menstrual symptoms in the same year; pain and lower GI symptoms in the same 90 days; and episodes of pain separated by at least 6 months — are likely to be clinically useful, as pointers to a diagnosis in their own right. However, the fact that they can be derived from existing data means that they have potential to be included in diagnostic support software within GP records.23 This study did not have sufficient cases to split the data into derivation and test sets, but future studies can use these composite features to test their predictive value in larger and better linked datasets. Additionally, machine learning techniques have a potential value in feature reduction and model selection.24,25 Ultimately, the aim must be to apply these observations within predictive models for earlier referral and diagnosis of endometriosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the expert clinicians and representatives of Endometriosis UK for their interviews.

Funding

This study was funded by the Chief Scientist Office of NHS Scotland through its first health informatics call (reference HICG/1/25). The funder played no role in conducting the research or in writing the article.

Ethical approval

The study involved analysis of anonymised data. Access to the data was approved by the Research Applications and Data Management Team at the University of Aberdeen.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What’s the delay? A qualitative study of women’s experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pugsley Z, Ballard K. Management of endometriosis in general practice: the pathway to diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(539):470–476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staal AH, van der Zanden M, Nap AW. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2016;81(4):321–324. doi: 10.1159/000441911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballard KD, Seaman HE, de Vries CS, Wright JT. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study — Part 1. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1382–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1292–1299. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a critical narrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(6):625–639. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas S, Ihle P, Köster I, Schubert I. Prevalence and incidence of diagnosed endometriosis and risk of endometriosis in patients with endometriosis-related symptoms: findings from a statutory health insurance-based cohort in Germany. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;160(1):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemaire GS. More than just menstrual cramps: symptoms and uncertainty among women with endometriosis. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(1):71–79. doi: 10.1177/0884217503261085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Kennedy SH, et al. Developing symptom-based predictive models of endometriosis as a clinical screening tool: results from a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):692–701. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta D, Hull ML, Fraser I, et al. Endometrial biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(4):CD012165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(2):CD009591. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009591.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch M, Begum MR, Paniz E, et al. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: a systematic review of international and national guidelines. BJOG. 2017 Jul 29; doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballard K, Lane H, Hudelist G, et al. Can specific pain symptoms help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? A cohort study of women with chronic pelvic pain. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapron C, Souza C, Borghese B, et al. Oral contraceptives and endometriosis: the past use of oral contraceptives for treating severe primary dysmenorrhea is associated with endometriosis, especially deep infiltrating endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(8):2028–2035. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sleeman D, Moss L, Aiken A, et al. Detecting and resolving inconsistencies between domain experts’ different perspectives on (classification) tasks. Artif Intell Med. 2012;55(2):71–86. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reis BY, Kohane IS, Mandl KD. Longitudinal histories as predictors of future diagnoses of domestic abuse: modelling study. BMJ. 2009;339:b3677. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton C, Cochran AJ, Cameron IM. Restarting antidepressant treatment following early discontinuation — a primary care database study. Fam Pract. 2015;32(5):520–524. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sleeman D, Moss L, Sim M, Kinsella J. Predicting adverse events: detecting myocardial damage in intensive care unit (ICU) patients; KCAP 2011, the Sixth International Conference on Knowledge Capture; 2011; Banff, Alberta, Canada. New York: ACM Press; pp. 73–79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feblowitz JC, Wright A, Singh H, et al. Summarization of clinical information: a conceptual model. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(4):688–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirsch JS, Tanenbaum JS, Lipsky Gorman S, et al. HARVEST, a longitudinal patient record summarizer. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):263–274. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton W. The CAPER studies: five case-control studies aimed at identifying and quantifying the risk of cancer in symptomatic primary care patients. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(Suppl 2):80–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nurek M, Kostopoulou O, Delaney BC, Esmail A. Reducing diagnostic errors in primary care. A systematic meta-review of computerized diagnostic decision support systems by the LINNEAUS collaboration on patient safety in primary care. Eur J Gen Pract. 2015;21(Suppl):8–13. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2015.1043123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell TM. Machine learning. Boston: WBC/McGraw-Hill; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darcy AM, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Machine learning and the profession of medicine. JAMA. 2016;315(6):551–552. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]