Abstract

Symptomatic β-thalassemia is one of the globally most common inherited disorders. The initial clinical presentation is variable. Whereas common hematological analyses are typically sufficient to diagnose the disease, sometimes the diagnosis can be more challenging. We describe a series of patients with β-thalassemia whose diagnosis was delayed, required bone marrow examination in one affected member of each family, and revealed ringed sideroblasts, highlighting the association of this morphological finding with these disorders. Thus, in the absence of characteristic congenital sideroblastic mutations or causes of acquired sideroblastic anemia, the presence of ringed sideroblasts should raise the suspicion of β-thalassemia.

Keywords: sideroblastic anemia, ringed sideroblasts, thalassemia

Introduction

Thalassemias and hemoglobinopathies are extremely common, affecting hundreds of millions of individuals worldwide1. α- and β-thalassemias are inherited forms of anemia arising from defective synthesis of α- or β-globin chains, respectively. β-thalassemia ranges in severity from asymptomatic conditions (heterozygous) thalassemia minor or trait, to severe transfusion-dependent forms termed thalassemia major. Phenotypes between these extremes are defined as thalassemia intermedia, usually characterized by mild to moderate anemia, transfusion independence and iron overload2,3. Complete blood count parameters, hemoglobin electrophoresis and globin chain mutation detection are typically sufficient to diagnose thalassemias. The pathogenesis of β-thalassemia involves an excess of α-globin compared to β-globin chain synthesis and/or stability that leads to ineffective erythropoieisis and decreased red blood cell survival. In some situations, particularly those associated with uncommon α-globin locus amplifications, even a molecular diagnosis can be evasive. Here we describe a series of thalassemia syndromes, for which patients underwent bone marrow sampling, and in which ringed sideroblasts, the hallmark of another group of anemias—the sideroblastic anemias—were detected prior to the discovery of a genotype diagnostic of β-thalassemia.

Patient descriptions

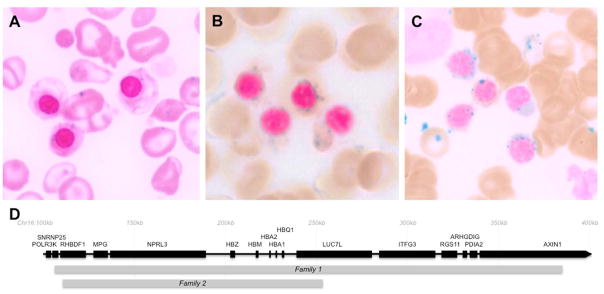

Patient 1 is a 34 year-old man with a history of normo/macrocytic anemia since birth (Figure 1A). He was diagnosed with hemolytic anemia, iron overload and presumptive β-thalassemia trait (Table 1). He underwent splenectomy and cholecystectomy during childhood. At the age of 28 years, bone marrow examination showed occasional ringed sideroblasts. Congenital sideroblastic anemia (CSA) mutations were excluded by sequencing.4 Copy number analysis using the Affimetrix 6.0 array revealed a duplication of ~179kb on chromosome 16p (GRCh37/hg19; chr16: 107,000–386,423) encompassing the entire α-globin gene locus and all or part of 10 other genes (Figure 1D), resulting in four copies of α-globin on this allele. No copy number alterations were detected at the β-globin locus. HBB sequence analysis showed the common β-globin nonsense mutation, c.118C>T, p.Q40X [HVGS nomenclature]; codon39 (C>T); Gln>STP [HbVar nomenclature]. Analysis of parental samples demonstrated that the α-locus duplication and β-globin mutation were from his Irish mother and Italian father, respectively. These findings indicate that he has β-thalassemia intermedia caused by heterozygous β-thalassemia trait and an α-chain excess. He has needed blood transfusions only twice in his life: at the age of 9 years for an aplastic crisis due to parvovirus infection, and at the age of 27 years after carbon monoxide poisoning. His current medications are deferasirox, for non-transfusional iron overload and hydroxyurea, which ameliorates his anemia.

Figure 1. Siderocytes and ringed sideroblasts in patients with β-thalassemias.

(A) Iron-stained peripheral blood smear from patient 1 demonstrating hypochromic microcytic anemia with numerous nucleated RBCs and abundant sideroctyes. (B &C) Iron-stained bone marrow aspirates from patients 5 and 6, respectively showing coarse perinuclear deposits of iron, typical of ringed sideroblasts. (D) Diagram of the α-globin locus and flanking regions on human chromosome 16. Genes are indicated by black bars and regions duplicated in families 1 and 2 are indicated by gray bars.

Table 1. Demographic, hematological, biochemical, and genetic features of patients.

Hematological values are at the time of diagnosis except patient 6, who was already chronically transfused. Hct, hematocrit; Hb, Hemoglobin; TIBC, Total Iron binding concentration.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6* | Patient 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | F | M | F | F | F | M |

| Race | White | White | White | White | White | Asian | White |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic (Italian, Irish) | Non-Hispanic (Italian, Irish) | Non-Hispanic (Greek) | Non-Hispanic (Greek) | Non-Hispanic | Chinese | Non-Hispanic |

| Age at onset (yrs) | birth | 2 | birth | birth | 0.17 | 2 | 1 |

| Age at diagnosis (yrs) | 31 | 32 | 13 | 9 | 0.75 | 7 | 6 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 6.4 |

| Hct (%) | 22.7 | 23.5 | 25.5 | 25.9 | 17.2 | 19.4 | 18.6 |

| MCV(fL) | 96 | 102.6 | 60.1 | 70.2 | 74.1 | 91 | 79.5 |

| HbA (%) | 64.9 | 60.5 | 84 | 68 | 92.1 | 94.3 | 88 |

| HbA2 (%) | 3.7 | 2.1 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| HbF (%) | 25.8 | 37.4 | 10.5 | 28.3 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 9.7 |

| β-globin genotype | c.118C>T/+ | c.118C>T/+ | c.315+1G>A/+ | c.315+1G>A/+ | c.92+1G>A/ c.92+6T>C | c.126_129delCTTT/ c.316–197C>T | c.444A>C/+ |

| α-globin genotype | αααα/αα | αααα/αα | αααα/αα | αααα/αα | αα/αα | αα/αα | αα/αα |

| Age at iron evaluation (yrs) | 32 | 32 | 17 | 12 | 1 | 9 | 8 |

| Iron (μg/dL) | 253 | 125 | NA | NA | 238 | NA | NA |

| TIBC (μg/dL) | NA | 264 | NA | NA | 254 | NA | NA |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 772 | 192 | 614 | 1567 | 604 | 1816 | 1639 |

| Hepatic Iron (mg/g dry wt) estimated by T2 MRI | 7.3 | 4.6–5.2 | 2.5 | < 2 | NA | 2.4 | 19.13–28.47 |

| Cardiac T2 MRI (msec) | 33 | 30 | NA | NA | NA | >50 | 37–41 |

| TX ever | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| TX chronically | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Splenectomy | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cholecystectomy | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Chelators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Hydroxyurea | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

Patient 2 is a 35 year-old woman, sister of patient 1. At the age of 2 years she was found to have hemolytic anemia with macrocytosis. Like her brother, she underwent splenectomy and cholecystectomy during childhood. Molecular testing decades later revealed the same β-globin mutation and α-globin gene duplication. Although they share the same genetic pattern, she has required many blood transfusions during infections and her two pregnancies. Presently, she is not regularly transfused and her current medications are deferasirox and hydroxyurea. Her last hepatic and cardiac MRIs were normal.

Patient 3 is a 17 year-old Greek male of consanguineous parentage with microcytic anemia since birth. At the age of 7 years he was found to have a heterozygous HBB c.315+1G>A (IVS-II-1 G>A) splicing mutation. He underwent bone marrow examination twice because his anemia severity was not explained by this molecular result. At 7 years many ringed sideroblasts were detected, while 4 years later they were no longer visible. CSA mutations were excluded. At the age of 13 years, genetic testing identified an ~140kb duplication of the α-globin locus and all or part of four contiguous genes (GRCh37/hg19; chr16: 110,690–253,576). This duplication is entirely within the region duplicated in patients 1 and 2 and, in combination with β-thalassemia trait, is responsible for his severe anemia and ineffective erythropoiesis. Since he was 9 years old he has been regularly transfused and on deferasirox for iron overload.

Patient 4 is a 12 year old girl, sister of patient 3. She was diagnosed prenatally with β-thalassemia trait. She presented microcytic anemia at birth. At 9 years of age she was found to share the same genetic pattern as her brother. She is regularly transfused since the age of 8 years and she is currently taking deferasirox with benefit.

Patient 5 is a 1 year-old girl who was diagnosed with severe microcytic anemia at the age of 2 months. At 8 months, bone marrow aspiration revealed the presence of numerous ringed sideroblasts (Figure 1B). Because of persistently elevated hemoglobin F (HbF) and (retrospectively discovered) increased hemoglobin A2 in both parents, testing for HBB mutations was performed and led to diagnosis of β-thalassemia due to two β-globin splicing mutations: c.92+1G> [IVS-I-1 (G>T)] and c.92+6T>C [IVS-I-6 (T>C)]. The first is a β0 allele, while the second is the Portuguese type β+-mutation that reduces the efficiency of splicing at a 5′ splice donor site. She is regularly transfused every 3–4 weeks and is not yet on chelators given her young age. Liver and cardiac MRI have not been performed.

Patient 6 is a 10-year-old Chinese girl. At the age of 2 years, at the time of adoption, a normocytic anemia of uncertain etiology was detected and she was started on regular transfusions. Bone marrow examination, repeated twice, demonstrated presence of ringed sideroblasts (Figure 1C). At 7 years of age genetic testing was performed and two β-globin mutations were found: c.126_129delCTTT (p.F42LfsX19) [codons 41/42 (-TTCT)] frameshift and c.316-197C>T (IVS II-654 C>T). Both of these severe β-thalassemia mutations are common in China. She is maintained on chronic transfusion and has been on chelators since she was 5 years old and her hepatic and cardiac MRIs are normal.

Patient 7 is a Caucasian 6-year-old boy diagnosed with chronic normocytic anemia at the age of 1 year. At 3 years of age, bone marrow aspiration showed only erythroid hyperplasia. He started regular transfusions and chelation at age 5 years. Bone marrow examination was repeated at age 6 years and revealed increased storage iron and ringed sideroblasts. Research genetic testing excluded known sideroblastic anemia mutations. Because of persistently elevated HbF, HBB was sequenced and showed a novel β-globin mutation: c.444A>C (p.X148YextX21 [beta stop codon STP>Tyr-Ala-Arg-Phe-Leu-Ala-Val-Gln-Phe-Leu-Leu-Lys-Val-Pro-Leu-Phe-Pro-Lys-Ser-Asn-Tyr-STP]), a stop-loss mutation. No abnormal hemoglobins were detected on hemoglobin electrophoresis. Common α-globin triplications were excluded by genomic PCR.5 The exact mechanism(s) whereby this and other C-terminal beta globin mutations cause anemia is not always evident. Absence of the variant peptide may indicate an unstable protein variant leading to β-globin deficiency, while a thalassemia-like loss of expression is also possible. Segregation analysis demonstrated that this mutation was de novo, suggesting that the phenotype is dominant. His hepatic MRI shows iron overload.

Discussion

We present a series of challenging thalassemia diagnoses. Unusual features that contributed to the delay in diagnosis included: presentation at birth or early infancy (Patients 1, 3, 4, and 5), macrocytosis (patients 1, 2, and 6), only one parent with β-thalassemia trait or β-globin mutation by sequencing (patients 1, 2, 3, and 4), consanguinity and only one demonstrable β-thalassemia allele, or absence of the abnormal hemoglobin on routine electrophoresis (patient 7). Apart from patients 2 and 4, who were ascertained as siblings, these patients had bone marrow aspiration to better understand their anemia. In each case, ringed sideroblasts were detected.

Ringed sideroblasts are erythroblasts with pathologic iron deposits in mitochondria and can be found in CSAs, myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative disorders, drug-induced anemia and metabolic abnormalities such as copper deficiency or alcoholism.6,7 They typically result from defects in protoporphyrin synthesis, iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis, or mitochondrial protein synthesis.8 Only one thalassemia patient with ringed sideroblasts has been reported: a 5 year-old Korean girl with mild anemia and iron overload, heterozygous for an initiation codon missense β0 allele (c.2T>G [beta Initiation codon Met>Arg]).9 The presence of ringed sideroblasts in patients with β-thalassemia is almost certainly under-recognized because bone marrow examination is usually not required for the diagnosis. In addition, as in patient 3, the presence of ringed sideroblasts may be transient. In several of these cases, a clue to the proper diagnosis was an increase in HbF, which is not typically seen at very high levels in CSA (M.D.F., unpublished observation)

In transfusion-dependent patients, iron overload develops after 1–2 years of regular transfusions,10 but hemosiderosis is also present in non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients, likely because anemia and ineffective erythropoiesis cause suppression of hepcidin and increased iron absorption.11,12 Iron toxicity from hemosiderosis seems to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) in bone marrow,13–16 worsening ineffective erythropoiesis by apoptosis induction. ROS damage due to iron overload may be an explanation for impaired heme synthesis or other mitochondrial defects, leading to sideroblasts production in thalassemia, but further studies are needed to better understand and characterize these mechanisms.

Thalassemia is a common disease, but occasionally the diagnosis can be challenging. CSA is comparatively very rare. Based on our experience in nearly 200 individuals diagnosed with CSA based on bone marrow findings, <3% have a beta-thalassemia genotype. Nonetheless, these patients highlight that ringed sideroblasts can be detected in thalassemic patients and that in the absence of sideroblastic anemia mutations or other known causes of ringed sideroblasts, their presence should raise the suspicion of β-thalassemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the participation of the patients and their families without whom the study would not be possible. Susan Wong is acknowledged for her deft management of the patient sample repository, and Jill Falcone for oversight of the Genetic Basis of Blood Disease protocol at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Research support

This work was supported by NIH DK087992 to M.D.F.

Abbreviations

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Statement of informed consent

All participants provided written informed consent to participate under the auspices of human subject research protocols approved at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Author contributions

K.C. assembled and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. D.R.C. performed all sequence analyses and was supervised by M.D.F. K.S.-A. performed copy number analysis (Variant Explorer pipeline) and was supervised by K.M. M.M.H, H.M.Y., A.E.C.B, S.K, K.W., and E.J.N. ascertained and phenotyped the patients. M.D.F. and E.J.N. supervised all work and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Weatherall DJ. The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are an emerging global health burden. Blood. 2010 Jun 3;115(22):4331–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-251348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musallam KM, Rivella S, Vichinsky E, Rachmilewitz EA. Non-transfusion-dependent thalassemias. Haematologica. 2013 Jun;98(6):833–44. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.066845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vichinsky E. Non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia and thalassemia intermedia: epidemiology, complications, and management. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(1):191–204. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1110128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergmann AK, Campagna DR, McLoughlin EM, et al. Systematic molecular genetic analysis of congenital sideroblastic anemia: evidence for genetic heterogeneity and identification of novel mutations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010 Feb;54(2):273–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Ma ES, Chan Ay, Prior J, et al. Single tube multiplex-PCR screen for anti-3.7 and anti-4.2 alpha globin gene triplications. Clin Chem. 2003;49(10):1679–82. doi: 10.1373/49.10.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottomley SS, Fleming MD. Sideroblastic anemia: diagnosis and management. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014 Aug;28(4):653–70. v. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuijpers ML, Raymakers RA, Mackenzie MA, de Witte TJ, Swinkels DW. Recent advances in the understanding of iron overload in sideroblastic myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2010 May;149(3):322–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming MD. CSAs: iron and heme lost in mitochondrial translation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:525–531. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon IS, Nam KL. Ringed sideroblasts found in a girl heterozygous for the initiation codon (ATG-->AGG) beta0-thalassemia mutation. Hemoglobin. 2007;31(3):383–6. doi: 10.1080/03630260701462105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tubman VN, Fung EB, Vogiatzi M, et al. Guidelines for the Standard Monitoring of Patients With Thalassemia: Report of the Thalassemia Longitudinal Cohort. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015 Apr;37(3):e162–9. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heeney MM. Iron clad: iron homeostasis and the diagnosis of hereditary iron overload. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014 Dec 5;2014(1):202–9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camaschella C, Nai A. Ineffective erythropoiesis and regulation of iron status in iron loading anaemias. Br J Haematol. 2016 Feb;172(4):512–23. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tehranchi R, Invernizzi R, Grandien A, et al. Aberrant mitochondrial iron distribution and maturation arrest characterize early erythroid precursors in low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2005 Jul 1;106(1):247–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hershko C. Pathogenesis and management of iron toxicity in thalassemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Aug;1202:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okabe H, Suzuki T, Uehara E, Ueda M, Nagai T, Ozawa K. The bone marrow hematopoietic microenvironment is impaired in iron-overloaded mice. Eur J Haematol. 2014 Aug;93(2):118–28. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chai X, Li D, Cao X, et al. ROS-mediated iron overload injures the hematopoiesis of bone marrow by damaging hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in mice. Sci Rep. 2015 May 13;5:10181. doi: 10.1038/srep10181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]